Abstract

Implementing safety management (ISM Code) aims to promote a good safety culture in the maritime industry. However, although this has improved safety, it has also paradoxically increased bureaucracy and overlooked operative personnel. At the same time, safety science has undergone a paradigm shift from Safety-I, which is traditional and error based, to Safety-II, which focuses on the potential of the human element. To determine whether Safety-I is dominant in the prevailing culture, or whether any Safety-II ideas are emerging, we studied the current thinking and the prerequisites for improving maritime safety culture and safety management. We interviewed 17 operative employees and 12 safety and unit managers (n = 29), both individually and in groups, in eight Finnish maritime organisations representing the maritime system (shipping companies, authorities, vessel traffic service, association). We also analysed 21 inspection documents to capture practical safety defects. To the employees, safety culture meant openness and well-functioning, safe work. However, this was not always the case in practice. Safety management procedures were portrayed as mainly technical/authority focused, and as neglecting the human element, such as the participation of operative personnel in safety improvements. We also found several factors that support improving maritime safety culture. The ISM code seems to have supported traditional methods of safety management (Safety-I), but not the creation of a positive safety culture, which the Safety-II paradigm has highlighted. System-wide safety improvement, participation of the operative personnel and open sharing of safety data were the areas in need of development. These were already being created in and among maritime organisations. To improve maritime safety culture in a concrete way and to achieve Safety-II in practice, we need a new focus and competence. Policy, procedures, and practical tools and models should use the human element as potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

1.1 Challenges in implementing safety management in maritime

Maritime safety has been the focus of continuous international attention in recent years due to widely publicised incidents such as the sinking of the South Korean M/S Sewol in 2014 with 304 fatalities, the fire on the car ferry Norman Atlantic in 2014 on the Mediterranean Sea, and the Costa Concordia accident on 13 January 2012 (TheGuardian 2014, 2015a, b; Schröder-Hinrichs et al. 2012). In order to improve safety in the maritime field, the International Safety Management codeFootnote 1 (the ISM Code; IMO 1993, 1995/2014) has been established. When it was launched, there was a strong belief that implementing a safety management system (SMS) would lead to a safety culture (Anderson 2003; Oltedal 2011; Kongsvik et al. 2014; Lappalainen 2016).

According to the obligatory ISM Code, a company is responsible for developing, applying and maintaining an SMS to ensure the safe operation of its ship, and for creating a safe working environment, protecting its workers from all identified risks, and ensuring the continuous improvement of the safety management skills of the personnel working on board and on shore (IMO 1993, 1995/2014). The company or shipowner must also adhere to the provisions of the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC), which include requirements for occupational health and safety protection and accident prevention, such as establishing a safety committee, represented by seafarers on board a ship, to hold meetings concerning the safety of the ship (MLC 2006).

Although the ISM Code came into effect 20 years ago, it seems that its principles and aims were not implemented properly in the cases mentioned above. Schröder-Hinrichs et al. (2012) claim that a combination of different human factors (HF) were behind the Costa Concordia accident. HF have often been recognised in incidents and accidents in safety-critical fields (Reason 1997, 2008; Dekker 2002; Teperi 2012). The most recent accident indicates that regulations alone do not guarantee absolute maritime safety.

Incidents and accidents also happen in Finland. Although, according to the Finnish Transport Safety Agency (Trafi), the level of maritime safety has remained at a good, stable level in recent years, 41 maritime accidents occurred in Finnish territorial waters in 2016 and 31 accidents occurred in 2017 (Trafi 2014, 2017). Luckily, none of these were classed as serious or very serious. The Finnish Accident Investigation Board (AIB) has identified several factors that contribute to deviations, such as a lack of communication and an inconsistent understanding of situations among the work team, and working practices that lag behind the technological development of the industry, all of which reflect poorly implemented SMS and a poorly developed safety culture (AIB 2009).

The implementation of the SMS required by the ISM Code has been studied widely in the maritime industry, and it seems that the ISM code has improved maritime safety culture. A recent questionnaire study indicated positive results in terms of the level of safety culture in the Finnish shipping industry (Teperi et al. 2016). Internationally, several studies have found benefits from implementing the ISM code (Kongsvik et al. 2014; Størkersen 2018). Other studies have shown that there is a great deal of room for improvement in safety management practices (Goulielmos and Gatzoli 2013; Schröder-Hinrichs et al. 2012; Lappalainen 2016). Specifically, there is a need to improve incident reporting, and studies have indicated that “fear of blame” hinders the reporting of incidents (Anderson 2003; Ek and Akselsson 2005; Bhattacharya 2009, 2011; Oltedal and McArthur 2011; Lappalainen et al. 2011) and that the social relations of employment and organisational factors underpin this fear of blame (Bhattacharya 2011). Furthermore, Almklov et al. (2014) found that implementing SMS based on a generic safety management regime may lead to disempowerment of employees and their perspectives.

Studies have also indicated that SMS implementation has caused excessive documentation and that this increased paperwork has led to a bureaucratic culture (Kongsvik et al. 2014). This documentation does not reflect ships’ real-life operations (Knudsen 2009; Batalden and Sydnes 2014) and seems to have displaced the common sense incorporated in local practices (Kongsvik et al. 2014). The personnel may see the requirements of the various instructions as distrust towards their own competence and professional skills (Bhattacharya 2009). Some signals also show that the strict compliance with SMS demanded by the clients of the shipping companies and implemented through top-down management has placed too much pressure on seafarers and weakened their occupational safety and health (Bhattacharya and Tang 2013).

In recent years, the concept of resilience and the Safety-II paradigm have challenged the traditional way of thinking about safety management and safety culture. According to Hollnagel (2014), the traditional approach to safety management is characterised by the concept of Safety-I, which focuses on reactive responses and strives to improve safety through eliminating risks and the causes of human failures or errors. The concept of Safety-II, in contrast, focuses on factors that create and maintain safety and considers humans a resource for successful performance (Hollnagel 2014; Schröder-Hinrichs et al. 2015). Its approach is to focus on systems’ functional and successful actions rather than on risks and errors. Although the Safety-I perspective may neglect the human potential of the system’s safety (Hollnagel et al. 2006; Hollnagel 2014; also Reason 2008), Hollnagel (2014) suggests that organisations should not replace it, but compliment their SMS with the Safety-II perspective, which focuses on understanding human variability, local knowledge and work-as-done. It must be understood that the Safety-I approach cannot be completely abandoned. Technical specifications in the design of a ship often need prescriptive regulations. The ISM Code should also be seen in a wider, global perspective. Nevertheless, despite the fact that the ISM Code should be the key instrument for introducing a Safety-II perspective in the maritime domain, research on the implementation of the ISM Code and a safety culture that focuses on the Safety-II approach is sparse (Schröder-Hinrichs et al. 2015).

We could conclude that the prevailing safety management practices have led to a bureaucratic culture in which the operative personnel seek to avoid errors and attempt to manage audits and investigations (Bhattacharya 2011; Almklov et al. 2014). It is obvious that a new focus is needed in safety management implementation and research (Teperi 2012, 2018; Teperi et al. 2015). Teperi et al. (2017a, b) have proposed that the Safety-II approach and HF should be incorporated into safety management practices (see also Teperi 2016; Teperi et al. 2018). Human activities, from a system and learning perspective, are considered necessary approaches in the development of safety culture (Hollnagel 2009; Leveson et al. 2006). Even though the Safety-II approach is not new, practical examples of how to apply it are lacking (Teperi 2018). Our study attempts to address this shortage.

The ability of personnel to impact the ways in which work is organised and conducted is essential for maintaining personnel work motivation and well-being (Glendon and Clarke 2016 referring to Karasek model). In the maritime field, seafarers’ active participation in safety management is crucial but may be severely limited (Bhattacharya and Tang 2013). Which parts function and maintain safety remains unknown, although the new safety paradigm underlines this perspective.

Maritime safety studies from the Safety-II perspective have not been implemented. These would highlight the supporting factors, successes and positive factors that maintain safety and strengthen a more favourable safety culture.

1.2 Aim of the study

This study is part of the SeaSafety research project (Teperi et al. 2016) conducted in 2015–2017, which aimed to gain an insight into Finnish maritime safety culture. The research project had three parts: Study I examined the maritime safety climate using a questionnaire (Teperi et al. 2016), Study II (this study) aimed to determine the basic assumptions of a safety culture using qualitative methods such as interviews and document analysis, and Study III tested HF-focused, participative intervention tools (for example the HF-tool) for maritime safety improvements (Teperi et al. 2017b; Teperi and Puro 2016).

The starting point for our study was the abovementioned questionnaire study, targeted at the Finnish maritime sector (Teperi et al. 2016). We used the Nordic Safety Climate Questionnaire (NOSACQ-50) as our research method (NFA 2017). The study indicated rather high scores in all dimensions in comparison to the grand means of the NOSACQ-50 database (NFA 2017). We considered it important to study the conditions of these surprisingly high results.

Another starting point for our study was the fact that internationally, previous studies had characterised the prevailing maritime safety culture as bureaucratic, as avoiding errors, and as being part of the elite’s top-down culture, which ignores operative personnel. To investigate how to improve this situation, we decided to start from the bottom by investigating the operative personnel’s conceptions of safety culture and safety management. We investigated how familiar the interviewees were with the safety management practices and which of them they considered important. We believed that their perceptions of the important practices would indicate the prevailing culture and reveal whether Safety-I was dominant, or whether any Safety-II ideas were emerging. Similarly, we thought that by investigating their conceptions of the prerequisites (hindering and supporting factors) for improving maritime safety culture, we could determine the possibilities to promote resilience, Safety II and the HF approach in safety management in the maritime industry. To verify our interview findings, we examined the inspection documents of maritime operations to determine how the inspections and the inspection reports indicated the prevailing safety culture.

Our detailed research questions were:

-

1.

How do maritime organisations define safety culture?

-

2.

How do the inspection documents of maritime operations indicate the current state of the safety culture?

-

3.

What safety management practices do maritime organisations currently use?

-

4.

What are the prerequisites (hindering and supporting factors) for improving maritime safety culture?

2 Material and methods

2.1 Participants

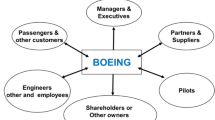

In 2016, we interviewed 29 study participants in 18 individual and group interviews in eight Finnish maritime organisations: Trafi, the Administrative Agency, vessel traffic services (VTS Centre), three shipping companies (from small to large, passenger and cargo), the Passenger Ship Association, and the Department of Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) of the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

We interviewed 17 operative employees (including captains, deck officers, engineering officers, and crew members, i.e. catering, deck and engine staff working onboard) in two shipping companies. Five participants from operative personnel were interviewed individually, and the rest in two group interviews (with five and seven participants) on board a ship. Twelve safety managers/DPAs,Footnote 2 a unit manager, and maritime and OSH inspectors working onshore were also interviewed in the eight maritime organisations. We call these 12 “key actors”. We did not distinguish between the private sector and the regulators when processing the data, because of the small sample sizes and ethicality of the study. The interviews were conducted face to face and mainly took place at the workplaces of the actors (office/offshore).

2.2 Conceptions of safety culture, safety management practices and prerequisites for improving maritime safety culture: interviews

We studied the conceptions of safety culture in the eight maritime organisations by interviewing the key maritime safety actors (12 participants). In the interviews of the operative personnel (17 participants), the themes were approached from a more practical perspective when working offshore (examples of interview items in Table 1).

We also elicited the views on the current safety management practices of both the key actors and operative personnel in the interviews. After obtaining an overall picture of the established SMS procedures, we added detailed questions, to obtain a clearer conception of the single components of the SMS.

The interviewees revealed several best practices and strengths when describing their SMS; these we consider supporting factors for improving safety culture.

We then studied the prerequisites for improving safety culture by asking the key actors and operative personnel about the factors that either hinder or support the improvement of safety culture. The hindering factors are summarised in Table 5, and the supporting factors are described in Sect. 3.4.

2.3 Maritime inspection documents indicating the current state of safety culture: document analysis

We studied indications of safety culture by analysing the inspection reports of the maritime operations. Inspection reports reveal how safety issues are dealt with on ships, i.e., whether employers have fulfilled their legal responsibilities. By studying inspection reports, we aimed to capture practical safety defects and to verify the interview findings. By examining the inspection reports, we also found the issues on which inspectors focus during their inspections. We believe that the defects mentioned in these reports reflected the ship’s safety culture and were thus one manifestation of the organisation’s current safety culture. In Finland, the Administrative Agencies’ main way of ensuring that safety regulations are followed at workplaces is inspections. These are performed by the Agency’s inspectors in co-operation with the employers and employees. The inspector writes the inspection report on the basis of the findings. In this study, we analysed 21 inspection reports of maritime operations in 2015 and 2016. The documents were randomly selected by the Administrative Agency representative but had to include reports written by several different inspectors. This ensured a diverse picture of the current safety culture level, which was independent of the work orientation or methods of a single inspector.

2.4 Analysis and summary of data used in study

The development of safety culture is not easy to research, as the subject cannot be approached by solely quantitative methods or controlled settings (Schein 1992; Zwetsloot 2014). Thus, we collected and analysed qualitative data, including document analysis, individual interviews, and group discussions, utilising the ideas of mixed method and data triangulation of qualitative research (Denzin and Lincoln 2011). By combining data collected through different methods, we aimed to cancel out the respective weaknesses of each method (Teddlie and Tashakkori 2011; Denzin and Lincoln 2011) and to provide an understanding of the issues that need further examination in future studies (Vicente 1997).

We transcribed all the material and categorised all the interviews into tables describing the main contents for each theme of this study. In the final tables, we used frequencies to describe how usual or rare certain types of conceptions were in the data. Finally, we compared the contents summarised in the tables to the theoretical discussion and research on safety and safety culture theories: the views of HF, resilience and Safety-II thinking in particular (Hollnagel et al. 2006; Hollnagel 2014; Teperi 2012; Teperi et al. 2018).

Figure 2 summarises the main findings of the qualitative data (interviews, document analysis) of this study and highlights the future development needs of maritime safety and its safety culture. Table 1 below summarises the research questions, the data used to study each research question and the analysis of this data (and how it is reported in this study/table or figure), and presents examples of detailed interview themes.

3 Results

3.1 Definitions of safety culture in maritime organisations

We asked the interviewees about their conceptions of safety culture, and these are summarised in Table 2. The numbers in the table columns represent the number of answers: How many key actors (DPA, manager) and captains or operative employees (catering/deck/engine) gave this type of conception in their answer. Each respondent could give multiple conceptions.

The studied maritime organisations did not use the term safety culture actively; it was even regarded as abstract, and they had many different conceptions of safety culture and safety. Several interviewees mentioned practical safety issues as elements of safety culture, such as safe working conditions, well-defined safety procedures and ensuring safety. Safety culture is believed to include all types of safety: both ship safety and the safety of passengers and crew members.

The interviewees’ definitions of safety culture emphasised openness and transparency as important elements. As one key actor described: “With regard to safety culture, there’s no blame culture in our company, which means that we are open and act fairly. That’s our guiding light and principle”.

The key actors and captains claimed that safety culture was estimated on the basis of compliance with standards and regulations. One key actor said: “There are specific norms, regulations, requirements, which we have to follow. And then we look at whether these norms are complied with. Based on this we can estimate how good our safety culture is”. The operative personnel similarly felt that safety management was tightly defined by regulations, inspections and documentation. Bureaucracy and documentation were mentioned as having increased significantly.

Safety was seen as everyone’s concern and as requiring everyone’s commitment. The operational personnel recognised the impact of their own activity on other people’s safety and on the safety of the vessel. Two key actors pointed out that safety culture begins from top management.

3.2 Safety culture evaluated via maritime inspection reports

After evaluating the conceptions of safety culture, we wanted to see how these views were reflected in practice, and used maritime inspectors’ documents to evaluate the implementation of the safety culture conceptions. The 21 inspection documents included 81 defects, of which 14 were requests and 67 were guidelines for employers. Most (26%) of these defects involved the safety of machines, tools and devices (Fig. 1; Table 3), 12% involved the working environment on the vessels, and 10% involved residential facilities and food services.

The defects found in the safety of machinery and tools were, for example, a lack of protective devices when working with machines, or a lack of machine safety inspections. The work environment on board ships revealed defects such as a lack of guards, or inadequate ergonomics in the office. The employer’s general obligations were mentioned when, for example, occupational health care documentation was missing. Table 3 shows examples of these defects.

The defects in the inspection reports show shortcomings in employers’ duties. These were mostly technical shortcomings, which could be checked during the inspections. Meanwhile, psychosocial factors, for example stress regarding working hours, were not determined.

3.3 Current safety management procedures and practices

We further wanted to evaluate the implementation of SMS as a reflection of safety culture and asked the interviewees about their SMS, safety procedures and the practices implemented in their organisation or on board their ship. These conceptions are summarised in Table 4. We also recorded some detailed items of the SMS (reporting deviations, investigating incidents, safety discussions, norms; items detailed in Sect. 2.4) and have included this detailed information in the text after Table 4.

Most of the interviewees claimed that the SMS was established (Table 4). In one organisation, it was still in progress. Both the key actors and the operative personnel indicated commitment to SMS: “It’s the master’s role to facilitate and manage the SMS (interviewee, key actor),” and “Everyone understands the importance of the SMS tools”. (interviewee, operative personnel).

Most of the interviewees (both the key actors and the operative personnel) described the reporting system. They also mentioned unofficial ways of reporting, such as diaries, phone calls and the post box in the mess room, deviations which were not documented in official databases. When asked for more detail, they revealed that the master was the one to report in their system; the operative personnel did not directly report deviations. The interviews also revealed several kinds of reporting systems, and various ways in which to define safety deviations (defects, incidents, accidents, non-conformity, observations; related to process, maritime, occupational, passenger safety or economical risks), and that it was not always clear to operative personnel which form to fill in for the various situations.

Audits and inspections were mentioned often (e.g., emergency equipment check-ups and vessel inspections), as were guidelines and checklists. Although they were regarded as useful, many felt that there were too many of them: “Paperwork is increasing in a crazy way; you’re filling in forms all the time”. (interviewee, operative personnel).

Several interviewees related that investigations were conducted mainly by the DPA of the shipping company, while more severe cases were investigated by Trafi or the AIB. Safety meetings for handling deviations or occupational safety incidents were held weekly or every 3 weeks and were initiated by the master. Emergency rehearsals, for example, training in operative situations such as blackouts or man-overboard situations were also mentioned; these were held every week. Some interviewees talked about discussions after incidents or deviations, mostly the key actors; these meetings were for learning, refreshing routines and raising awareness of the significance of concentration and fatigue, etc. Other SMS procedures mentioned were induction training and co-operation between masters.

One interesting finding was that one small, and old shipping company had a very functional, light version of the SMS in use, although it was not mandatory at the time of the study (it had been earlier). Their conceptions of safety management highlighted the role of top management and deep, committed family company values related to production, client orientation, service quality, and safety.

3.4 Prerequisites for improving safety culture (hindering and supporting factors)

We first asked the interviewees which factors they saw as hindering safety improvements or the implementation of safety management procedures, and which they saw as weaknesses, or which issues should be facilitated in the future. The interviewees’ responses are summarised in the categories below (Table 5). The extracts from the interviews explain the findings.

Financial and scheduling pressures were most frequently mentioned as a hindrance to safety improvements. This was especially the case in small shipping companies that might be forced to make savings in safety solutions. As one interviewee from operative personnel said: “It depends on money, there should be one man more, we had one before, but he was taken away. Now recovery is impossible”. Financial and scheduling pressures were also reflected by fatigue: Savings were made by reducing crew resources, and sleeping conditions on the vessels were unsuitable for recovery. Economic reasons were also behind using mixed crews (members of different nationalities), which caused communication problems and differences in working habits, ways of organising work and fulfilling responsibilities. Safety was seen as requiring a common language and a shared understanding, and the interviewees felt that some cultures could not admit their own errors, as this would mean “losing face”.

Many of the interviewees saw that SMS did not work. They often reflected that a weak reporting system hindered safety improvement. Reporting was considered laborious and the reporting threshold too high, and the interviewees said that the master decided which issues to report and wrote the reports. The seafarers in the group interview discussed the issue: “That (reporting incidents) has been quite weak. If something really serious happens, only then we report, but otherwise it’s quite sparse. Earlier, it actually happened orally and then the first officer made some kind of report”. Although it was recommended that reporting to the top management of the shipping company took place via the DPA, in reality, it was not clear to DPAs whether deviations on the ships were reported. Currently, personnel did not report to the authority. It was also claimed that corrective actions were put into practice without reporting or documentation. As one key actor said, “How does the ISM code appear to the seafarer, does the organisation provide real prerequisites and tools for action?” (interviewee, key actor).

It was quite often mentioned that competence was lacking in developing management, actions, information flow or combining subcultures on the ships. For example, it was felt that development needs were discussed but not put into action; actions took time or were not congruent with the original proposal. One interviewee from operative personnel mentioned: “Those papers (reported incidents) are sent by e-mail but several just remain on the captain’s table”. In the group interview, the operative personnel explained “It depends on who’s driving the ship. Sometimes you have to check, who’s in charge and whom you can talk to. It depends on the person… who is interested”.

Several interviewees, both key actors and operative personnel, mentioned the “old hierarchical maritime culture” (direct quote) as a hindrance. It was also felt that the development needs of the operative personnel were not listened to. In their group interviews, the seafarers claimed that: “Maritime is still one of the most hierarchical fields in the world, it should be modernised, in 2016 it cannot be that one person gives the orders and others obey. They’d save a lot of resources if they just asked for the personnel’s opinions”. The hierarchy was also described as: “The wrong people make the decisions, the personnel on the ship knows the issues, they are not listened to enough, all the decision are made at the head office”.

We then asked the interviewees which factors facilitated or supported safety improvements or the implementation of safety management procedures. The responses are summarised below. Open discussion, the fact that issues and opinions regarding lessons learnt were shared, and mutual help and information flow were considered factors that supported safety improvements. One interviewee described the situation: “I sent all the January reports to the ships, summarised them as a booklet and sent it. And also gave it to our group of executives, and they were very, very satisfied, and this is the way we are currently proceeding, because ships have asked for this for several years now” (interviewee, key actor).

Training and competence were also seen as supporting factors; competence levels were increasing, as was the eagerness to share views and raise opinions, which was a result of this better competence. One interviewee explained that “Younger workers are much more enlightened. The training of the younger first officers and chief engineers has probably handled these occupational safety issues more, as well as human factors. So, they can now take those issues into account, and the resistance was originally more from the older workers, who have now retired, they agitated the younger ones…”

Co-operation and system-level activities between different partners (maritime authority, foundations), the fact that actors knew each other well in a small country and successful recruitment (e.g., giving a realistic picture of the demands of work at sea) were also mentioned. All these issues were raised by four interviewees representing key actors.

Other experienced strengths were (mentioned by two key actors) the key persons’ commitment to safety, functional investigation of all incidents (by AIB, Trafi or the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health), regulations, documentation and guidelines. Systematic organisation, proactiveness and putting plans into action were also mentioned as factors that support the improvement of safety culture. One key actor from the shipping company described good systemic co-operation: “Trafi inspectors have demanded that we fulfil the requirements; actually we’ve become closer, we have good co-operation with more discussion, we have pondered different choices together, we have gained guidance on how to implement demands in practice”.

As supporting factors, the following were also mentioned: a strong company culture in which top management is committed to overall improvements, safety being part of all activities and resources, and mandates being available if something has to be improved. The operative personnel listed checklists, job permissions, inspections, audits and checking equipment as factors that supported safety.

The interviewed key actors and operative personnel also spontaneously revealed strengths and best practices during the interview, for example, teamwork, mutually distributed knowledge of one another’s work, competence and vigilance, and group discussions after incidents (defusing) were mentioned. Some system-level developments were in progress; for example, the VTS Centre and Trafi played an active role in inviting maritime partners to think together about solutions to acute problems.

3.5 Summary: current state and development needs of safety culture

Figure 2 presents a summary of the main findings of the interviews and document analysis. The box on the right contains the ideas for development needs determined from the study findings. These are examined in more detail in the Sects. 4 and 7.

Although our document analysis showed practical examples of defects in compliance with regulations and the interviews provided further information on the hindering factors behind these defects, the interviews also revealed supporting factors that can be interpreted as a signal of a new, positive maritime safety culture.

4 Discussion

The starting points for our study were on the one hand the rather high results of the current level of safety culture in the Finnish maritime sector (Teperi et al. 2016), and on the other hand, the fact that previous studies have shown that internationally, the prevailing maritime safety culture can be characterised as bureaucratic, error avoiding and as representing the elite’s top-down culture, which ignores the operative personnel (Bhattacharya 2011; Batalden and Sydnes 2014; Kongsvik et al. 2014; Almklov et al. 2014).

4.1 Conceptions of safety culture in maritime organisations

The first focus of our study was the interviewees’ conceptions of safety culture. As it was supposed that the implementation of the ISM Code would promote safety culture in the maritime industry, we believed that the interviewees’ perceptions could provide us with important signs regarding the kind of safety culture that existed, and how this safety culture could be characterised.

This study indicated that the concept of safety culture is not in common use in the maritime organisations studied. Safety culture was considered abstract, and the interviewees’ conceptions seemed to be vague and fragmented. In summary, safety culture was seen as a certain way of acting in safety matters; valuing safety and appreciating it in everyday work, and being able to work in a safe workplace. In more detail, the interviewees mostly defined safety culture as openness, fairness, everyone’s commitment to safety, and fluency in everyday work processes.

On the other hand, some of the responses indicated a compliance culture, an administrative and procedural way of improving safety, also noted by Antonsen (2009) and Schröder-Hinrichs et al. (2015). The interviewees often emphasised compliance with norms and guidelines when evaluating their safety culture; the operative personnel felt that regulation defined safety management. The technological and procedural contribution dominated the conceptions of the interviewees, and human performance was not the focus. Kirwan (2003) and Teperi et al. (2017a) found similar conceptual domination in the nuclear industry, Teperi (2012) also in air traffic management, and Hollnagel (2009) in the health care sector, despite the fact that safety frameworks have been shifting from technical analysis to aspects such as HF, safety culture and system analysis already for some time (Hollnagel et al. 2006; Hollnagel, 2014; Hale and Hovden 1998).

4.2 Evaluating safety culture on the basis of maritime inspection reports

The results of the first research question showed that the interviewees regarded fluency of work and a safe work environment as the most significant characteristics of a good safety culture, but we found that these factors were not actually realised in practice. The second research question investigated how the inspection documents of maritime operations indicated the current state of the safety culture. By examining the inspection reports, we also found the issues on which inspectors focus during their inspections.

The document analysis revealed technical shortcomings, defects in the work environment on the vessels or the lack of guidance or documentation on safety issues. One of the main safety motivators for employees was adequate resources. Thus, providing knowledge and training in safety issues, as well as the regular safety checks required by law, may be interpreted as commitment on the part of management, and we assume that defects in these safety issues reflect the safety culture of the company. If the employer does not adhere to safety guidance, it is reasonable to assume that employees may not necessarily be able to perform their jobs safely.

Our results also raise a question concerning the inspections themselves. The inspections performed by the authorities seemed to highlight technical matters, and although these are important indicators of safety level (how the employer takes care of vessels and personnel, puts actions into practice), many psychosocial factors and HF remained absent from the inspection reports. It is widely known that HF at the individual, work, group, and organisational level, such as work satisfaction, communication and openness in the work community, as well as group dynamics, have been considerable causal factors of well-known accidents in safety critical areas such as aviation (Kirwan 2003; Reason 2008; Dekker 2002, 2007; Teperi et al. 2015) and the maritime field (Manuel 2011; Schröder-Hinrichs et al. 2012, 2013). However, inspections as a procedure do not reflect these key safety factors properly. The results of the document analysis indicated that the inspectors have (or have been forced to have) strong technical and compliance orientation in terms of the inspection and that they lack the capacities and competencies for human element issues. The audit system of inspection should be discussed. Most inspectors follow regulations that require them to focus on non-compliance by using checklists. This model of inspection can be questioned for its inability to provide a clear picture of safety.

Finally, we noticed that as a method, the inspections helped us determine the kind of issues on which inspectors’ work focuses, and the documents were an important indicator of maritime safety culture. The inspections stressed regulation compliance and focused on the accuracy of the documents, not necessarily on the work reality (how work is done; values in practice compared to espoused values; Argyris and Schön 1996; Antonsen 2009).

4.3 Current safety management procedures and practices

The third research question sought to investigate how familiar the interviewees were with the safety management practices and what safety management practices they considered important. We believe that their considerations of the important practices indicated what elements of safety culture were dominant in the daily operations in the prevailing culture, whether Safety I was dominant, or whether any Safety II ideas were emerging.

Guidelines, standard operational procedures and processes, as well as audits, inspections, check-ups and investigations, were frequently mentioned as safety management practices and procedures in active use, indicating that these are well established practises of safety management—and mainly represent the Safety-I perspective, as they focus on avoiding errors and risks. Reporting deviations and incidents (including deviations concerning e.g. cargo and actions of the crew or passengers) was also often mentioned as an SMS practice, but later, several problems were revealed in the reporting system, which may represent the weakest link in maritime safety management. This is the same finding as that of several other earlier studies (e.g. Anderson 2003; Ek and Akselsson 2005; Oltedal and McArthur 2011).

A smaller proportion of the findings concerned safety meetings with personnel, emergency rehearsals, discussing incidents or induction training. Even fewer comments concerned the supervisor’s role: his follow-up, feedback and arrangement of meetings. A few interviewees mentioned co-operation among captains and first officers, management’s safety reviews, safety discussions in the mess room or other unofficial discussions among personnel. This kind of employee empowerment and management commitment is considered one of the key factors in creating a good safety culture (Flin et al. 2000; Dekker 2002, 2007; Wiegmann et al. 2002; Antonsen 2009), also indicating Safety-II thinking, and would be an essential element in future work when proceeding to improve maritime safety culture.

4.4 Prerequisites for improving safety

We thought that by investigating interviewees’ perceptions of the prerequisites (hindering and supporting factors) for improving maritime safety culture, we could determine the possibilities to promote resilience, Safety II and a HF approach in maritime safety management. These have been topical issues in the maritime and other safety critical fields for some time (Dekker 2002, 2007; Hollnagel 2014).

To better understand the development needs of maritime safety culture, we asked the interviewees what they saw as the factors that hinder the improvement of safety. Although they recognised that a functional reporting system was the cornerstone of SMS, they felt this kind of active reporting system was lacking; minor deviations were not reported, and operative personnel did not report incidents themselves, but via the master. It is obvious, that openness and the participation of the operative personnel should be increased, to determine indicators of “work-as-done” and local knowledge, which is highlighted in the Safety-II perspective. Evidence-based, practical examples of how this is implemented with participative methods have been described in several workplace interventions (see for example Teperi and Leppänen (2011) in air traffic control, Teperi et al. (2017a) in nuclear industry and Teperi et al. (2017b); Teperi and Puro (2016) in maritime). As safety meetings with seafarers’ representation are demanded by MLC (2006), one way in which to proceed would be for administration, HR and/or occupational health and safety officers (presumably with the help of external HF experts) to arrange roundtable discussions together with operative personnel instead of strict auditing meetings with the aim of checking compliance. Development needs and action plans for these, delivered bottom up (as in Teperi and Leppänen 2011), would highlight seafarers’ practical needs in terms of work and safety.

An old hierarchical maritime culture, slow changes in ways of thinking and a feeling of not being able to influence changes were often mentioned in the interviews, and earlier studies have found these same signals (e.g., Kongsvik et al. 2014; Almklov et al. 2014). Based on these results, it seems that the ISM code has failed to offer ways for operative personnel to participate or to give them an active role to play in fulfilling the aims of safety management and that these kinds of procedures and practices are still in progress. We must remember that the ISM is only a framework, which shipping companies and other maritime actors try to follow and implement in varying ways. But, do officers’ professional orientation and competence support this kind of participative development? If not, shipping companies should have well-established ways (tools, models, processes and practices) with which to involve their personnel in safety. The key to this development would be to support the creation of positive safety thinking by, for example, also reporting successes and fluent work processes, not only incidents, risks and errors, as this may encourage a blame culture and feelings of guilt among operative personnel (as in aviation, Teperi et al. 2015; the nuclear industry, Teperi et al. 2017a, 2018; and other fields, Teperi 2016; 2018).

The interviewees felt that several safety problems were due to commercial and client pressures, an issue also found earlier by Bhattacharya and Tang (2013). According to some, the shipping companies had strict budgets and attempted to make savings at the expense of safety, and others felt that sales were prioritised. Some companies used heterogeneous crews as this lowered costs, but having several different cultures within teams caused practical challenges to work routines and communication. Resting periods were also neglected during work shifts, and fatigue and time pressure were seen as hindering factors. The same factors were found by Bhattacharya (2011) who claimed that sociological factors influence the practice of incident reporting in the shipping industry.

The supporting factors described by the interviewees indicated that open discussions, good team performance on ships and the maritime system level among actors already existed. This development should be more strongly supported and strengthened in the future. Open discussion, the fact that issues and opinions regarding lessons learnt were shared, and mutual help and information flow were considered factors that supported safety improvements. Training and competence were also seen as supporting factors; competence levels were increasing, as was eagerness to share views and raise opinions, which was a result of this better competence. Co-operation and system-level activities between different partners (maritime authority, foundations), the fact that actors knew each other well in a small country, and successful recruitment were also mentioned. Other experienced strengths were the key persons’ commitment to safety, functional investigation of all incidents (by AIB, Trafi or the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health), regulations, documentation, and guidelines. Systematic organisation, proactiveness and putting safety plans into action were also mentioned as functional factors of safety culture.

It is interesting that without being asked directly, the interviewed key actors and operative personnel spontaneously revealed strengths and best practices during the interview, for example, teamwork, mutually distributed knowledge of one another’s work, competence and vigilance, and group discussions after incidents (defusing). Some system-level developments were in progress; for example, the VTS Centre and Trafi played an active role in inviting maritime partners to think together about solutions to acute problems. Their role could be even stronger in future maritime safety improvement.

All the factors revealed in this study indicate that motivation and competence for proceeding with maritime safety culture improvements exists, and thus it is important to strengthening these factors in the future.

5 Methodological comments

In the first part of this research project (SeaSafety, Study I; Teperi et al. 2016, see details in Sect. 1.2), we noticed the limitations of quantitative methods for assessing safety culture and its artefacts. The complexity of using questionnaires that were too extensive, with too many items, has also been criticised by Nielsen et al. (2016). In this study, we used qualitative methods (interviews, document analysis) to determine the conceptions and orientations of maritime safety culture (i.e., basic assumptions about levels of safety culture; Schein 1992; Guldenmund 2010).

The results of this study revealed that using mixed methods for studying safety culture can provide a multifaceted “bigger picture” of the safety culture process and its phenomena, which is not possible using only single methods (Antonsen 2009; Guldenmund 2010; Zwetsloot 2014). This study also had a multi-skilled research group, consisting of a psychologist, an expert in maritime studies, and engineers. Furthermore, we had different maritime actors, from shipping companies to VTS, authorities and associations representing the maritime system. We highly recommend this systemic method for other future safety culture research.

The use of document analysis as part of determining safety culture needs to be examined in more detail. The conclusions we drew on the basis of the inspectors’ documents may be questioned, because we had no standard level of how many inspection observations would reflect a poor or good safety culture. Thus, we decided to use the documents to indicate the object reality on the ships, the work environment that the interviewees also stressed in their safety culture definitions. Finally, we noticed that as a method, the inspections helped us identify the kind of issues on which inspectors’ work focuses, and the documents were an important indicator of maritime safety culture. The inspections stressed regulation compliance and focused on the accuracy of documents, and not necessarily on the work reality (how work is done; values in practice compared to espoused values; Argyris and Schön 1996; Antonsen 2009). Finally, the documents highlighted technical issues rather than psychosocial factors or HF, despite these having long been the focus of safety science (Dekker 2002, 2007; Reason 2008; Hollnagel et al. 2006; Schröder-Hinrichs et al. 2012, 2013). The weakness of our document analysis was that it only used OSH inspections, and no other inspections made by maritime inspectors, classification societies or clients such as oil majors.

We used slightly different interview themes for key actors and operative personnel. We tried to focus on the work orientation of the group, rather than asking the ship personnel overly-abstract questions. The interviews of the operative personnel revealed positive indications of safety management on vessels, even before we asked about supporting factors at the end of the interview. Stressing risk factors may also reflect the domination of individual- and error-based Safety-I thinking among the researchers themselves (Hollnagel 2014; Almklov et al. 2014; Teperi et al. 2017a, b).

6 Future research and practical implications for maritime organisations

As the weaknesses of open sharing and reporting have long been prevalent phenomena in maritime, we conclude that a new kind of positive safety thinking is needed; one that uses concrete tools to support the creation of a just culture by including the operative personnel bottom-up, through open sharing (Teperi et al. 2015, 2017a, b; Teperi and Puro 2016). Aviation has implemented a wide lessons-learnt culture, more actively than many other safety-critical fields (Teperi and Leppänen 2010; Dekker 2007). One part of this is a system in which operative personnel report not only within their own organisation but also directly to their authority (with the idea that they are heard, their proposals are implemented and their reports influence decision-making). This kind of process was still in progress in the Finnish maritime industry at the time of this study, when legislation was undergoing changes. However, there has been much debate on decreasing regulation (also in the rail sector and aviation in general) in such a way that the actors themselves could take more responsibility for their own functions, and the role of regulator/authority would shift from traditional controlling to auditing system indicators (not operative details), and mentoring and supporting the actors.

Balancing business and safety is an enormous theme, and we were unable to examine it in greater detail in this article. Nevertheless, we found several indications of problems connected to fatigue and crew resources, and safety solutions to these challenging issues would demand wide-ranging system-level co-operation in the future (through open and fair co-operation among medical experts, authorities, shipping companies, foundations and trade unions).

What should be done? Who should do it? To achieve an accurate, systematic line of improvements, we suggest development measures at all levels: those of policy, procedure and operations.

We make the following proposals:

-

At the international maritime level, IMO should proceed with revising the ISM code, applying modern safety culture and human element competence (see e.g. ICAO 2009; Schröder-Hinrichs et al. 2013; Teperi et al. 2017a, b)

-

At the national level, authorities could play an even more active role in supporting operative personnel and highlighting local knowledge and work-as-done. One way in which to implement this would be to make a continuous effort to promote safety by using multimethod scales to monitor safety and safety culture levels. The different maritime partners should have joint tools, system co-operation and learning practices.

-

At the local level, in shipping companies, joint forums should be set up that utilise group techniques (e.g. work process analysis; Teperi and Leppänen 2011) in which the work processes and development needs of operative personnel (including safety issues) are made visible and put into practice. On board ships, supporting democratic dialogue requires the authority and role of the captain to be flexible in normal to risky situations, which in turn demands awareness of different work roles.

-

At the individual level, good competence, responsibility and activeness in safety issues should be promoted by both the organisation and the maritime system.

7 Conclusion

In this study, we found that although the implementation of the ISM code has promoted safety culture in the Finnish maritime sector, maritime safety culture has not yet proceeded from Safety-I thinking to Safety-II, despite this perspective being highlighted in current safety research. First, the focus of safety management is on technical issues rather than on improving resilience. Second, faith in rules and compliance is strong. Third, safety is currently more often managed in a top-down than bottom-up manner. Fourth, human performance is seen as error based, and this hinders open, participative safety improvements. Is the ISM code missing its potential to improve the safety level of the maritime field? In the future, the code could apply more to modern safety thinking (Safety-II), which consists of proactive, systemic and participative co-operation and learning processes that focus on the human element and work-as-done. The scope should shift to cover actionable factors. This new scope demands new practical frameworks and tools for safety experts, and management by regulatory bodies, shipping companies, research institutes and maritime education. In practice, bottom-up workplace interventions should be conducted which take the local knowledge of the operative personnel better into account in decision-making and everyday work. Concretely applying HF at individual, work, group and organisational levels in SMS may be a practical way in which to proceed to the Safety-II perspective (Teperi et al. 2015, 2017b, 2018), as factors supporting and maintaining safety are the focus. However, previous or current maritime safety studies have not shown this aspect, and the Safety-II literature does not contain many practical examples of implementations. To improve maritime safety culture in a concrete way, policy, procedures, and practical, concrete tools and models need to be used through co-operation with maritime actors, on all levels of the maritime system. We have made suggestions in this article for how each maritime system level can achieve this improvement.

Notes

The International Management Code for the Safe Operation of Ships and for Pollution Prevention (International Safety Management (ISM) Code)

References

AIB (2009) The impact of accident investigation on domestic passenger ship safety, Accident Investigation Board (AIB). In Finnish with abstract in English. Available at: http://www.turvallisuustutkinta.fi/material/attachments/otkes/tutkintaselostukset/fi/vesiliikenneonnettomuuksientutkinta/2009/s12009m_tutkintaselostus/s12009m_tutkintaselostus.pdf. Accessed 24 Nov 2018

Almklov PG, Rosness R, Størkersen K (2014) When safety science meets the practitioners: does safety science contribute to marginalization of practical knowledge? Saf Sci 67:25–36

Anderson P (2003) Cracking the code. The relevance of the ISM code and its impact on shipping practices. Nautical Institute, London

Antonsen S (2009) Safety culture: Theory, method and improvement. CRC Press. Taylor and Francis

Argyris C, Schön DA (1996) Organisational learning II: theory, method and practice. Addison-Wesley, Reading

Batalden BM, Sydnes AK (2014) Maritime safety and the ISM code: a study of investigated casualties and incidents. WMU J Marit Aff 13(1):3–25

Bhattacharya S (2009) Impact of the ISM Code on the Management of Occupational Health and Safety in Maritime Industry. Doctoral thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff

Bhattacharya S (2011) Sociological factors influencing the practice of incident reporting: the case of the shipping industry. Employee Relations 34(1):4–21

Bhattacharya S, Tang L (2013) Fatigued for safety? Supply chain occupational health and safety initiatives in shipping. Econ Ind Democr 34(3):383–399

Dekker S (2002) The field guide to human error investigations. Ashgate publishing Ltd, Aldershot

Dekker S (2007) Just culture. Balancing safety and accountability. In: Ashgate Publishing, Cornwall

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (2011) The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks Apr 27, 2011 - mathematics - 766 pages

Ek Å, Akselsson R (2005) Safetey culture on board six Swedish passenger ships. Marit Policy Manag 32(2):159–176

Flin E, Mearns K, O’Connor P, Bryden R (2000) Measuring safety climate: identifying the common features. Saf Sci 34(1–3):177–192

Glendon AI, Clarke SG (2016) Human safety and risk management. A psychological perspective, 3rd edn. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group

Goulielmos AM, Gatzoli A (2013) The “major maritime accidents” do not occur randomly. JESE-B 2(12):709–722

Guldenmund FW (2010) Understanding and exploring safety Culture. TU Delft, Delft University of Technology, Delft

Hale AR, Hovden J (1998) Management and culture: the third age of safety. A review of approaches to organizational aspects of safety, health and environment. In: Feyer A, Williamson A (eds) Occupational injury: risk, Prevention and Intervention. Taylor and Francis, London, pp 129–265

Hollnagel E (2009) ETTO-principle, efficiency thoroughness trade off. Why things go right sometimes go wrong. In: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, Farnham

Hollnagel E (2014) Safety-I and safety-II. The past and future of safety management. Ashgate

Hollnagel E, Woods DD, Leveson N (eds) (2006) Resilience engineering: concepts and precepts. Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Hampshire

ICAO (2009) Annex13, aircraft accident and incident investigation, edn 9

IMO (1993) The international management code for the safe operation of ships and for pollution prevention (international safety management (ISM) code), Resolution A741(18)

IMO (1995/2014) ISM Code and Guidelines on Implementation of the ISM Code 2014. Available at: www.imo.org/ourwork/HumanElement/SafetyManagement/Pages/ISMCode.aspx. Accessed 24 Nov 2018

Kirwan B (2003) An overview of a nuclear processing plant human factors programme. Appl Ergon 34:441–452

Knudsen F (2009) Paperwork at the service of safety? Workers’ reluctance against written procedures exemplified by the concept of ‘seamanship’. Saf Sci 47(2):295–303

Kongsvik TØ, Størkersen KV, Antonsen S (2014) The relationship between regulation, safety management systems and safety culture in the maritime industry. In: Steenbergen RDJM, va Gelder PHAJM, Miraglia S, Vrouwenvelder ACWM (eds) Safety, reliability and risk analysis: beyond the horizon. Taylor and Francis Group, London, pp 467–473

Lappalainen J (2016) Finnish maritime personnel’s conceptions on safety management and safety culture. Doctoral dissertation. Series 316, University of Turku

Lappalainen J, Vepsäläinen A, Salmi K, Tapaninen U (2011) Incident reporting in Finnish shipping companies. WMU J Marit Aff 10(2):167–181

Leveson N, Dulac N, Zipkin D, Cutcher-Gershenfeld J, Carroll J, Barrett B (2006) Engineering resilience into safety-critical systems. In: Hollnagel E, Woods DD, Leveson N (eds) Resilience engineering—concepts and precepts. Ashgate, Aldershot, pp 95–123

Manuel ME (2011) Maritime risk and organizational learning. Ashgate, London

MLC (2006) The Maritime Labour Convention 2006. International labour conference. 105 p. Cited 8.3.2017. Available at: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/%2D%2D-ed_norm/%2D%2D-normes/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_090250.pdf

NFA (2017). How to use NOSACQ-50. Interpreting the Nordic Occupational Safety Climate Questionnaire NOSACQ-50 results (2017, February 27). Nationale Forskningscenter for Arbejdsmiljø (NFA) (National Research Centre for the Working Environment). Retrieved from http://www.arbejdsmiljoforskning.dk/da/publikationer/spoergeskemaer/nosacq-50/how-to-use-nosacq-50/interpreting-nosacq-50-results ccessed 24 Nov 2018

Nielsen MB, Hystad SW, Eid J (2016) The brief Norwegian safety climate inventory (brief NORSCI)–psychometric properties and relationships with shift work, sleep, and health. Saf Sci 83:23–30

Oltedal, H. A. (2011). Safety culture and safety management within the Norwegian-controlled shipping industry. State of art, Interrelationships and Influencing Factors. (Doctoral Thesis), University of Stavanger, Stavanger

Oltedal HA, McArthur DP (2011) Reporting practices in merchant shipping, and the identification of influencing factors. Saf Sci 49(2):331–338

Reason J (1997) Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Ashgate, Aldershot

Reason J (2008) The human contribution: unsafe acts, accidents and heroic recoveries. Ashgate, Cornwall

Schein E (1992) Organizational culture and leadership, 2nd edn. Jossey-Bass. A Wiley company, San Francisco

Schröder-Hinrichs JU, Hollnagel E, Baldauf M (2012) From titanic to Costa Concordia—a century of lessons learnt. WMU J Marit Aff 11(2):151–167

Schröder-Hinrichs JU, Hollnagel E, Baldauf M, Hofmann S, Kataria A (2013) Maritime human factors and IMO policy. Marit Policy Manag 40(3):243–260

Schröder-Hinrichs JU, Praetorius G, Graziano A, Kataria A, Baldauf M (2015) Introducing the Concept of Resilience into Maritime Safety. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279282665_Introducing_the_Concept_of_Resilience_into_Maritime_Safety. Accessed 24 Nov 2018

Størkersen K (2018) Bureaucracy overload calling for audit implosion. A sociological study of how the international safety management code affects Norwegian coastal transport. PhD thesis. Norwegian University of Science and Technology

Teddlie C, Tashakkori A (2011) Mixed methods research: contemporary issues in an emerging field. . In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) the SAFE handbook of qualitative research. 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, p.285–300

Teperi A-M (2012) Improving the mastery of Hum Factors in a safety critical ATM organisation. Cognitive Science, Institute of Behavioural Sciences, Faculty of Behavioural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland. Doctoral dissertation

Teperi A-M (2016) Modifying human factor tool for work places—development processes and outputs. Injuryprev 22(Suppl 2):A216. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042156.603

Teperi A-M (2018) Applying human factors to promote a positive safety culture. Occup Environ Med 75(Suppl 2):A12.2–A1A12. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2018-ICOHabstracts.35

Teperi A-M, Leppänen A (2010) Learning at air navigation services after initial training. J Work Learn 22(6):335–359

Teperi A-M, Leppänen A (2011) From crisis to development—analysis of air traffic control work processes. Appl Ergon 42:426–436

Teperi A-M, Puro V 2016 Safely at sea: our role in creating safety. Finnish Institute of Occupational Health. Helsinki. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-261-712-5 (pdf). Accessed 24 Nov 2018

Teperi A-M, Norros L, Leppänen A (2015) Application of the HF tool in the air traffic management organization. Saf Sci 73:23–33

Teperi A-M, Puro V, Perttula P, Ratilainen H, Tiikkaja M, Miilunpalo P (2016) Merenkulun turvallisuuskulttuurin arviointi ja kehittäminen – parempaa turvallisuutta inhimillisten tekijöiden hallinnalla. Työterveyslaitos, Helsinki. /Assessing and improving maritime safety culture from human factors perspective. In Finnish with English summary. Research report for Finnish Work Environmental Fund. www.julkari.fi

Teperi A-M, Puro V, Ratilainen H (2017a) Applying a new human factor tool in the nuclear energy industry. Saf Sci 95:125–139

Teperi A-M, Puro V, Lappalainen J (2017b) Promoting positive safety culture in the maritime industry by applying the Safety-II perspective. In: Bernatik A, Kocurkova L, Jørgensen K (eds) (2017). Prevention of Accidents at Work: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on the Prevention of Accidents at Work (WOS 2017), October 3–6, 2017, Prague, Czech Republic. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Teperi A-M, Puro V, Tiikkaja M, Ratilainen H (2018) Developing and implementing a human (HF) tool to improve safety management in the nuclear industry. Research report, HUMTOOL-research project in SAFIR2018-research program http://www.julkari.fi/handle/10024/136178, Helsinki 2018. Accessed 24 Nov 2018

TheGuardian (2014) South Korea ferry disaster survivors describe chaotic scenes. 16.4.2014. Cited 28.2.2017. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/16/south-korea-ferry-sewol-disaster-chaotic-scenes-boat

TheGuardian (2015a) Costa Concordia: Italian Tragedy that reflected state of a nation. 11.2.2015. Cited 28.2.2017. Available at: www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/11/costa-concordia-italian-tragedy-that-reflected-state-of-a-nation

TheGuardian (2015b) Ferry fire near Spain forces more than 150 passengers to evacuate. 28.4.2015. Cited 28.2.2017. Available at: www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/28/spain-balearic-islands-ferry-fire-passengers-evacuated

Trafi (2014) Suomen merenkulun tila 2014 - turvallisuus ja ympäristövaikutukset. Trafin julkaisuja 11/2014. Liikenteen turvallisuusvirasto Trafi. 55 p. In Finnish

Trafi (2017) Merenkulun vuosi 2016: paljon pieniä onnettomuuksia. Liikenteen turvallisuusvirasto Trafi. Cited 28.2.2017. In Finnish. Available at: https://www.trafi.fi/tietoa_trafista/ajankohtaista/4644/merenkulun_vuosi_2016_paljon_pienia_onnettomuuksia

Vicente KJ (1997) Heeding the legacy of Meister, Brunsvik and Gibson: toward a broader view of human factors research. Hum Factors 39:323–328

Wiegmann D, Zhang H, von Thaden T, Sharma G, Mitchell A (2002) A synthesis of safety culture and safety climate research. University of Illinois, Aviation Research Lab, Savoy

Zwetsloot GIJM (2014) Evidence of the benefits of a culture of Prevention. In: Aaltonen M, Äyräväinen A, Vainio H (eds) From Risks To Vision Zero Proceedings of the International Symposium on Culture of Prevention – Future Approaches. Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Helsinki, pp 30–35

Acknowledgements

The authors also express their heartfelt thanks to all the eight participating organisations for their active participation throughout the project. Especially warm thanks go to the shipping companies for the opportunity to go offshore and familiarise ourselves with the operative environment.

Funding

This work was supported by the Finnish Work Environment Fund and the Finnish Transport Safety Agency Trafi for funding the SeaSafety research project in 2015–2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Teperi, AM., Lappalainen, J., Puro, V. et al. Assessing artefacts of maritime safety culture—current state and prerequisites for improvement. WMU J Marit Affairs 18, 79–102 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-018-0160-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-018-0160-5