Abstract

According to the World Health Organization, diabetes could be responsible for 1.5 mln deaths a year and prevalence of diabetes is still increasing. Improper diet is one of modifiable risk factors of type 2 diabetes. Because diabetes is a major health burden, research recognizing factors contributing to increased risk of type 2 diabetes is important. The aim of the study was conducting the comparison of intake of food groups between participants with normoglycemia, impaired fasting glucose (IFG), and type 2 diabetes of Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Poland population. Assessment of intake of food groups was conducted with the use of validated Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) among 1654 participants of PURE Poland—baseline (2007–2009). Assessment of the differences between groups had been performed with the use of the Kruskal-Wallis test. The significance level was established to be p ≤ 0.05. Participants with IFG in comparison to participants with diabetes consumed significantly more fruit juices, beverages with added sugar, sweets, honey, and sugar. Participants with IFG in comparison with normoglycemic participants consumed significantly more refined grains, fruit juices, lean meat, and processed meat and less nuts and seeds. Participants with diabetes in comparison to normoglycemic participants consumed significantly more lean meat and processed meat and less tea and coffee, alcohol, dried fruit, honey, sugar, and nuts. Especially participants with IFG, who consumed more products of high glycemic index should be the subject of intensive counseling and other prophylactic measures to reduce the risk of progression to type 2 diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 422 mln people worldwide have diabetes and the prevalence of this disease have rapidly risen in the last decades [1]. Diabetes is the main cause of kidney failure, blindness, lower limb amputation, and stroke and contributes strongly to other cardiovascular diseases [1]. Impaired fasting glycemia (IFG) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)—conditions preceding full-symptomatic type 2 diabetes—are considered independent risk factors for cardiovascular diseases [2], though according to recent meta-analyses, this association is rather moderate in comparison with diabetes [3]. There have been evidence that endothelial dysfunction caused by hyperglycemia and macrovascular lesions occur much earlier than previously thought—endothelial dysfunction develops already in prediabetic state [4]. According to the WHO, the modifiable risk factors that contribute to the development of diabetes can be included: tobacco smoking, overweight and obesity, low physical activity, and improper diet [1]. So-called western diet, rich in, e.g., saturated fatty acids, trans-unsaturated fatty acids, and refined grains, is associated not only with cardiovascular diseases but also with type 2 diabetes [5, 6], whereas Mediterranean diet is associated with much lower risk of those conditions [7]. Progression of impaired fasting glycemia and impaired glucose tolerance to full-symptomatic type 2 diabetes is not inevitable. Early behavioral intervention, like improving physical activity and changing dietary habits, can slow down or even cease the process of progression to type 2 diabetes [8]. Standards for diabetes management, not only Polish [9] but also international (e.g., Standards of American Diabetes Association [10]), emphasize the need for implementing intensive counseling regarding changing the lifestyle in prediabetic patients. Nutritional intervention includes, e.g., changing the quality of dietary fat, increased intake of wholegrain, high-fiber carbohydrate products and decreased intake of additionally sweetened beverages, sweets, and high processed products. The influence of consumption of individual food groups on the risk of type 2 diabetes differ from one group to another, as it was observed in many studies [11]. The aim of the study was to compare the intake of groups of dietary products between individuals with normoglycemia, impaired fasting glucose, and type 2 diabetic patients in the population of Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study.

Material and methods

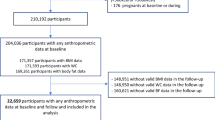

Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiology study engages 21 countries of different status of economic development and more than 150,000 participants worldwide. The study is designed to collect data in 3 years and intervolves and is planned for 12 years in total [12]. The Polish arm of the PURE study was established in 2007 at Wroclaw Medical University. The baseline cohort included 2036 participants, aged between 30 and 85 years, both from urban and rural area. All participants were examined according to the international PURE project protocol [13]. The paper presents the results of PURE Poland study—baseline, covering the group of 1654 participants, who completed the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) and had the blood test performed.

The Food Frequency Questionnaire consists of 154 dietary products, characteristic for Polish dietary habits. The FFQ was collected by trained staff and referred to dietary habits of 1 year prior to the interview. The FFQ was specially developed and validated for Polish population [14]. One hundred fifty-four dietary products were divided in 26 food groups (Table 1). The criteria for such specific division were not only dietary recommendations for general Polish population [15] but also standards for nutrition therapy in diabetes [9, 10]. We had taken into consideration, e.g., the glycemic index of the dietary products, the content of fiber, and quality of dietary fat. We gathered soups in one independent food group, because of their traditional and Polish-specific ingredients and way of preparation. Other traditional Polish dishes were included in the “mixed dishes” group. Because of different glycemic index and fiber content, we divided grains into “whole grains” and “refined grains,” similarly, fruits and vegetables were divided into “raw,” “cooked,” “dried,” and “juices.” Due to the quantity and quality of dietary fat, but also recommendations for Mediterranean diet, we divided dairy products into “low-fat” and “full-fat,” moreover, meats were divided into “lean meat,” “red meat,” and “processed meat.” Participants whose calorie intake assessed by FFQ was < 500 kcal/day or > 5000 kcal/day were excluded from analysis due to presumably unreliable interview.

Overall analysis concerned 1654 eligible participants: 992 with normoglycemia, 464 with IFG, and 198 with diabetes. People, whose fasting plasma glucose was between 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) and 125 mg/dL (6.9 mmol/L) were included into the group of participants with IFG. In the group of diabetes, there were included people whose fasting plasma glucose was ≥ 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L), or those who had already been diagnosed with diabetes in the past and had been undergoing treatment ever since. Participants with normal fasting plasma glucose (70–99 mg/dL, 3.9–5.5 mmol/L) and who were declared with no diabetes diagnosed in the past were included into the group of normoglycemia. A trained health professional, who performed examination, verified whether fasting prior to the examination lasted at least 8 h. Enzymatic hexokinase method was used to measure the fasting plasma glucose from venous blood with the use of Cobas machine and reagents (Roche Diagnostics).

Statistical analysis was performed with the use of Statistica 12.0 PL computer program. Assessment of the differences between groups had been performed with the use of the Kruskal-Wallis test. The significance level was established to be p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Study population consists of 1654 eligible participants: 36.2% of men and 63.8% of women (Table 2). Overall, 992 participants had normoglycemia (34.6% of men and 65.4% of women). Overall, 464 participants had IFG (37.1% of men and 62.9% of women). Overall, 198 participants had diabetes (41.9% of men and 58.1% of women).A total of 17.5% of participants overall were < 45 years old (73.4% and normoglycemia, 21.7% had IFG, and 4.8% had diabetes). Age group between 45 and 64 years old was the largest group: 66.9% of participants overall (57.8% with normoglycemia, 29.6% with IFG, and 12.6% with diabetes). Of the participants, 15.5% were older than 64 years (54.1% with normoglycemia, 28.4% with IFG and 17.5% with diabetes). A total of 55.9% of participants were urban dwellers and 44.1% were rural dwellers. Among urban dwellers, 69.0% had normoglycemia, 22.7% had IFG, and 8.3% had diabetes. Among rural dwellers, 48.6% had normoglycemia, 34.8% had IFG, and 16.6% had diabetes. Overall, 15.3% participants had primary education (46.6% with normoglycemia, 31.2% with IFG, and 22.1% with diabetes). Overall, 16.6% of participants had vocational education (53.5% with normoglycemia, 32.4% with IFG, and 14.2% with diabetes), while 39.0% of participants had secondary education (60.2% with normoglycemia, 28.8% with IFG, and 11.0% with diabetes). Total of 29.1% of participants had university degree (70.5% with normoglycemia, 22.9% with IFG, and 6.7% with diabetes).

Average BMI in groups of normoglycemia, IFG, and diabetes was 27.2, 29.2, and 31.6 kg/m2 respectively. The analysis revealed statistically significant differences in distribution of body weight between participants with normoglycemia, IFG, and diabetes (p < 0.000) (Table 3). The largest group with normal body weight was participants with normoglycemia (34.3 vs. 20.3% participants with IFG and 12.1% participants with diabetes) (Table 3). Obesity was more prevalent in participants with IFG (40.3%) and diabetes (57.6%), than in participants with normoglycemia (23.8%).

The analysis revealed statistically significant differences in consumption of 12 out of 26 food groups (Table 4). Participants with IFG in comparison to participants with diabetes consumed statistically significantly more fruit juices, beverages with added sugar, sweets, and honey/sugar. Participants with IFG in comparison with normoglycemic participants consumed significantly more refined grains, fruit juices, lean meat, and processed meat/charcuterie and significantly less nuts/seeds. Participants with diabetes in comparison to normoglycemic participants consumed significantly more lean meat, processed meat/charcuterie, and soups, while on the other hand, significantly less tea/coffee, alcohol, dried fruit, nuts/seeds, and honey/sugar. Simplified results of post hoc analyses are presented in Table 5.

Discussion

The comparison between consumption of food groups between participants with normoglycemia, IFG, and type 2 diabetes revealed significant differences in 12 out of 26 food groups.

Participants with IFG consumed more refined grains than normoglycemic participants. Refined grains are characterized by high glycemic index and deprivation of most of the dietary fiber and are not recommended, especially in the prevention and treatment of diabetes. According to the guidelines, whole grains should be the main source of carbohydrates [10]. Alminger et al. [16] observed that the intake of whole grains in comparison to refined grains is associated with much lower rise of postprandial glucose and insulin level. According to Wirström et al. [17], consumption of whole grains lowers the risk of development of prediabetes. Meta-analysis conducted by Yao et al. [18] concludes that increased intake of dietary fiber is associated with lower risk of development of type 2 diabetes. In a randomized, double-blind study conducted by Dainty et al. [19], participants who consumed bagels rich in resistant starch in comparison with participants who consumed regular bread were characterized by lower fasting and postprandial insulin levels and lower fasting insulin resistance. Participants with IFG consumed more fruit juices than either normoglycemic or diabetic participants.

It is already known that higher consumption of fruit and vegetables is associated with lower risk of metabolic diseases. Recently published meta-analysis, by Wang et al. [20], concludes that higher intake of raw fruit and vegetables (especially green leafy, yellow, and cruciferous vegetables) is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes. On the other hand, fruit juice is characterized by higher content of monosaccharides and lower content of fiber than raw fruit, which also results in higher glycemic index. Moreover, fruit juice frequently contains artificially added glucose-fructose syrup (or high-fructose corn syrup), which is cheaper than saccharose, in order to improve the taste of the juice. Meta-analysis performed by Imamura et al. [21], who assessed impact of consumption of soda and fruit juices on the risk of type 2 diabetes, adjusted for adiposity and calorie intake, concluded that both soda and fruit juices increase the relative risk for diabetes. In fact, increasing the intake of fruit juice by one serving a day was associated with 7% greater risk of type 2 diabetes. On the contrary, meta-analysis recently conducted by Wang et al. [22] provides no hard evidence for association between consumption of fruit juices and diabetes. Either way, overconsumption of fructose could be deleterious for the metabolic health. Although fructose has lower glycemic index than glucose, it is speculated that its consumption promotes deposition of lipids in visceral abdominal tissue and decreases glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity especially in overweight persons [23]. To sum up, excessive consumption of fruit juices, especially those with added sugar or glucose-fructose syrup, should not be recommended in patients with metabolic disorders. Consumption of highly sweetened beverages is one of the risk factors for overweight and obesity and is strongly unrecommended [1]. The herein analysis revealed increased consumption of beverages with added sugar by participants with IFG in comparison to diabetic patients. Meta-analysis of 11 cohort studies, performed by Malik et al. [24], concludes that among participants who consumed the highest amounts of sweetened beverages (one to two servings a day), the risk of development of type 2 diabetes was higher by 26%. Moreover, the Framingham Offspring Cohort study provided an observation that consumption of sweetened beverages increased the risk of development of prediabetes and insulin resistance by 46% in comparison to the risk of those who did not consume such beverages [25]. In the presented paper, participants with IFG consumed more sweets and honey/sugar than diabetic patients. Because of increasing consumption of sugar worldwide and association of higher consumption of sugar with increased risk of overweight/obesity and non-communicable diseases, the World Health Organization strongly recommends to limit consumption of free sugars to 10% of total energy intake (and states that ideal intake is below 5% of total energy intake) [26].

Either participants with IFG or diabetes consumed more processed meat and charcuterie than normoglycemic participants. Meta-analysis conducted by Feskens et al. [27] concluded that increased consumption of red meat and processed meat increases the risk of type 2 diabetes. According to the meta-analysis conducted by Micha et al. [28], every additional serving of processed meat per day increases the risk of diabetes by 19%. Possibly, the high content of saturated fatty acids and trans-unsaturated fatty acids in processed meat is a factor responsible for such association. Analysis performed by Guess et al. [29] concludes that higher consumption of saturated fatty acids is associated with higher fasting plasma glucose, hepatic insulin resistance, and higher plasma glucose after 2 h in oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Further non-nutritive compounds (differentiating processed meat from red meat), like sodium or nitrosamines, are candidate factors affecting metabolic disorders.

According to the herein findings, diabetic participants consumed significantly less alcohol than normoglycemic participants. As stated in recommendations for diabetic patients by the American Diabetes Association [10], excessive alcohol consumption should be strictly avoided (no more than two servings per day for men and no more than one serving per day for women). The findings presented in this paper suggest that it is possible that counseling introduced after diagnosis of diabetes influenced decreased consumption of alcohol. Excessive consumption of alcohol can increase the risk of delayed hypoglycemia in diabetic patients, especially those who use insulin [10]. Excessive consumption of alcohol should be avoided not only by diabetic patients but also by healthy population. According to findings from the Northern Swedish Cohort study [30], a 27-year prospective cohort study, increased consumption of alcohol and binge drinking behavior were associated with higher values of fasting plasma glucose among adult women. These findings were consistent with findings obtained by Baliunas et al. [31] in the meta-analysis of cohort studies. According to this meta-analysis, moderate consumption of alcohol decreases the risk of type 2 diabetes among women, but excessive consumption of alcohol significantly increases the risk of diabetes.

In the herein study, it was also observed that participants with diabetes consumed less tea and coffee than normoglycemic participants. There is evidence that drinking unsweetened tea and coffee can improve health status, presumably due to the high content of antioxidative compounds. However, the association between consumption of tea and coffee and incidence of type 2 diabetes needs further investigation, but there have been some observations that have emerged. Meta-analysis conducted by Yang et al. [32] concluded that consumption of at least three cups of tea per day can contribute to lower risk of type 2 diabetes. According to van Dieren et al. [33] and the Dutch arm of EPIC-NL study, which investigated more than 40,000 participants over a 10-year period, consuming at least three cups of tea or coffee decreased the risk of type 2 diabetes by 42%.

According to our findings, participants with diabetes consumed significantly less nuts and seeds than normoglycemic participants. It is not clear why diabetic participants consumed less of those products, but one of the reasons for such behavior could be an attempt to reduce the overall energy intake, since nuts and seeds are rather calorie-dense products. On the other hand, such behavior can deprive of some essential nutrients provided by nuts and seeds, e.g., polyunsaturated fatty acids. Results obtained within the Nurse’s Health Study [34] suggest that higher consumption of nuts is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes among adult women, though findings from the Physician’s Health Study found no such association among adult men [35]. A meta-analysis conducted by Wu et al. [36] also failed to find an association between consumption of nuts and risk of type 2 diabetes. On the other hand, the role of polyunsaturated fatty acids prevalent in nuts and seeds in lowering the risk of cardiovascular diseases is well established [37]. Since diabetic patients are at high risk of developing cardiovascular complications, including nuts and seeds in the diet is recommended in order to lower the risk of metabolic complications [38].

The participants with IFG consumed more food groups characterized by higher glycemic index in comparison with the participants with diabetes (fruit juices, beverages with added sugar, sweets) and normoglycemia (refined grains, fruit juices). On the other hand, diabetic participants were characterized by lower consumption of high glycemic index food groups, e.g., alcohol. These findings can suggest that dietary counseling introduced after diabetes diagnosis is—at least partially—effective and influences dietary choices of the participants. There is evidence in the literature that dietary counseling is effective not only in promoting diabetes management but also preventing progression to full-symptomatic diabetes [8]. According to the standards of diabetes care, both Polish [9] and American [10], intensive dietary and behavioral counseling should be introduced in prediabetic patients as soon as possible in order to prevent deterioration of glucose tolerance. Nevertheless, not all prediabetic patients are referred to dietary counseling. According to Ginde et al. [39], only 10% of the patients with incidentally diagnosed IFG or IGT in emergency ward received information about their condition and 6% were referred for further management. According to the results of NHANES study [40], 43.6% of patients with prediabetes and 10% of normoglycemic patients were informed about health risks of type 2 diabetes.

What is more, analysis revealed that obesity was more common in participants with IFG and diabetes than in normoglycemic participants, in fact there was a gradual increase in percentage of obese individuals along with deterioration of glucose metabolism (23.8% of individuals with normoglycemia, 40.3% with IFG, and 57.6% with diabetes were obese). Obesity is a major risk factor of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases [41], and cancer [42]. Both higher consumption of unrecommended food groups and high prevalence of obesity in IFG participants are alarming risk factors of metabolic deterioration.

Conclusion

The diets of participants with IFG were characterized by higher content of unrecommended food groups. The prevalence of obesity was much higher among participants with IFG and diabetes than participants with normoglycemia. Because of high risk of further metabolic deterioration, individuals with IFG should be the group of the highest priority for dietary and behavioral counseling in order to prevent progression to full-symptomatic type 2 diabetes.

Abbreviations

- IFG:

-

impaired fasting glucose

- FFQ:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- IGT:

-

impaired glucose tolerance

- PURE:

-

Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiology study

- OGTT:

-

oral glucose tolerance test

References

World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. Isbn [Internet]. 2016;978:88. Available from: http://www.who.int/about/licensing/%5Cn http://www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204871/1/9789241565257_eng.pdf.

Meigs JB, Nathan DM, D RB, Wilson PW. Fasting and postchallenge glycemia and cardiovascular disease risk: The Framingham Offspring Study. [cited 2017 Mar 25]; Available from: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/25/10/1845.full-text.pdf.

Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration TERF, Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SRK, Gobin R, Kaptoge S, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet (London, England) [Internet]. Elsevier; 2010 [cited 2017 Mar 25];375:2215–22. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20609967.

Su Y, Liu X-M, Sun Y-M, Wang Y-Y, Luan Y, Wu Y. Endothelial dysfunction in impaired fasting glycemia, impaired glucose tolerance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2017 Jun 3];102:497–8. Available from: https://www-1clinicalkey-1com-1scopus.han.bg.umed.wroc.pl/service/content/pdf/watermarked/1-s2.0-S0002914908006814.pdf?locale=en_US.

Kim JA, Kim SM, Lee JS, Oh HJ, Han JH. Dietary patterns and the metabolic syndrome in Korean adolescents. [cited 2017 Mar 25]; Available from: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/30/7/1904.full-text.pdf.

Hosseini Z, Whiting SJ, Vatanparast H. Current evidence on the association of the metabolic syndrome and dietary patterns in a global perspective. Nutr Res Rev [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 Jun 3];29:152–62. Available from: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S095442241600007X.

Giugliano JA, Goudevenos DB, Panagiotakos C-M, Kastorini HJ, Milionis K, Esposito D, et al. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components: the effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components. JAC [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017 Mar 25];57:1299–313. Available from: http://content.onlinejacc.org/cgi/content/full/57/11/1299.

Lindst JO, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, Rastas M, Salminen V, Eriksson J, et al. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity FOR THE FINNISH DIABETES PREVENTION STUDY GROUP. [cited 2017 Mar 25]; Available from: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/26/12/3230.full-text.pdf.

Diabetologiczne PT. Zalecenia kliniczne dotyczące postępowania u chorych na cukrzycę. Diabetol. Klin; 2016.

Cefalu W. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2016. Diabetes Care [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 Mar 25];39. Available from: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/suppl/2015/12/21/39.Supplement_1.DC2/2016-Standards-of-Care.pdf.

Schwingshackl L, Georg Hoffmann B, Anna-Maria Lampousi B, Knü ppel S, Khalid Iqbal B, Carolina Schwedhelm B, et al. Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 24];32. Available from: https://link-1springer-1com-1scopus.han.bg.umed.wroc.pl/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs10654-017-0246-y.pdf.

Teo K, Chow CK, Vaz M, Rangarajan S, Yusuf S, PURE Investigators-Writing Group. The Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study: examining the impact of societal influences on chronic noncommunicable diseases in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Am Heart J [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2017 Aug 23];158:1–7.e1. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19540385.

Zatońska K, Zatoński WA, Szuba A. Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiology Poland—study design. J Health Inequal. 2016;2:136–41.

Dehghan M, Ilow R, Zatonska K, Szuba A, Zhang X, Mente A, et al. Development, reproducibility and validity of the Food Frequency Questionnaire in the Poland arm of the Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological (PURE) study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2012;25:225–32.

M. Jarosz. Normy żywienia dla populacji polskiej – nowelizacja [Internet]. Inst. Żywności i Żywienia. 2012. Available from: http://www.izz.waw.pl/attachments/article/33/NormyZywieniaNowelizacjaIZZ2012.pdf.

Alminger M, Eklund-Jonsson C. Whole-grain cereal products based on a high-fibre barley or oat genotype lower post-prandial glucose and insulin responses in healthy humans. Eur J Nutr. 2008;47:294–300.

Wirström T, Hilding A, Gu HF, Östenson CG, Björklund A. Consumption of whole grain reduces risk of deteriorating glucose tolerance, including progression to prediabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:179–87.

Yao B, Fang H, Xu W, Yan Y, Xu H, et al. Dietary fiber intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a dose–response analysis of prospective studies. [cited 2017 Mar 25]; Available from: http://download-1springer-1com-1scopus.han.bg.umed.wroc.pl/static/pdf/672/art%253A10.1007%252Fs10654-013-9876-x.pdf?originUrl=http%3A%2F%2Flink.springer.com%2Farticle%2F10.1007%2Fs10654-013-9876-x&token2=exp=1490461399~acl=%2Fstatic%2Fpdf%2F672%2Fart%2525.

Dainty SA, Klingel SL, Pilkey SE, McDonald E, McKeown B, Emes MJ, et al. Resistant starch bagels reduce fasting and postprandial insulin in adults at risk of type 2 diabetes. J Nutr [Internet]. American Society for Nutrition; 2016 [cited 2017 Jun 7];146:2252–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27733521

Wang PY, Fang JC, Gao ZH, Zhang C, Xie SY. Higher intake of fruits, vegetables or their fiber reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig [Internet]. 2016;7:56–69. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4718092/pdf/JDI-7-056.pdf.

Imamura F, O ‘connor L, Ye Z, Mursu J, Hayashino Y, Bhupathiraju SN, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. bmj BMJ [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Jun 11]; Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/351/bmj.h3576.full.pdf.

Wang B, Liu K, Mi M, Wang J. Effect of fruit juice on glucose control and insulin sensitivity in adults: a meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials. [cited 2017 Mar 25]; Available from: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0095323&type=printable.

Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL, Griffen SC, Bremer AA, Graham JL, et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. 2009 [cited 2017 Jun 11];119. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2673878/pdf/JCI37385.pdf.

Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després J-P, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. [cited 2017 Mar 25]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2963518/pdf/zdc2477.pdf.

Ma J, Jacques PF, Meigs JB, Fox CS, Rogers GT, Smith CE, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage but not diet soda consumption is positively associated with progression of insulin resistance and prediabetes. J Nutr [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 Mar 25];146:2544–50. Available from: http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/doi/10.3945/jn.116.234047.

Brouns F. WHO Guideline: “sugars intake for adults and children” raises some question marks. Agro Food Ind Hi Tech. 2015;26:34–6.

Feskens EJM, Sluik D, Van Woudenbergh GJ. Meat consumption, diabetes, and its complications. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13:298–306.

Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. [cited 2017 Jun 11]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2885952/pdf/nihms203406.pdf.

Guess N, Perreault L, Kerege A, Strauss A, Bergman BC. Dietary fatty acids differentially associate with fasting versus 2-hour glucose homeostasis: implications for the management of subtypes of prediabetes. 2016 [cited 2017 Mar 25]; Available from: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/.

Nygren K, Hammarström A, Rolandsson O. Binge drinking and total alcohol consumption from 16 to 43 years of age are associated with elevated fasting plasma glucose in women: results from the northern Swedish cohort study. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Jul 6];17. Available from: https://link-1springer-1com-1scopus.han.bg.umed.wroc.pl/content/pdf/10.1186%2Fs12889-017-4437-y.pdf.

Baliunas DO, Taylor BJ, Irving H, Roerecke M, Patra J, Mohapatra S, et al. Alcohol as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. [cited 2017 Jul 19]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2768203/pdf/zdc2123.pdf.

Yang J, Mao Q-X, Xu H-X, Ma X, Zeng C-Y. Tea consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. [cited 2017 Jul 20]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4120344/pdf/bmjopen-2014-005632.pdf.

Van Dieren S, Uiterwaal CSPM, Van Der Schouw YT, Van Der DL, Boer JMA, Spijkerman A, et al. Coffee and tea consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes-NL Dutch Contribution to European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition FFQ Food-frequency questionnaire MORGEN Monitoring Project on Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases. [cited 2017 Jul 20]; Available from: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs00125-009-1516-3.pdf.

Jiang R, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Liu S, Willett WC, Hu FB. Nut and peanut butter consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. JAMA [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2002 [cited 2017 Jul 20];288:2554. Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.288.20.2554.

Kochar J, Gaziano JM, Djoussé L. Nut consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in the Physicians’ Health Study. [cited 2017 Jul 20]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2802656/pdf/nihms-137818.pdf.

Wu L, Wang Z, Zhu J, Murad AL, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, et al. Nut consumption and risk of cancer and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev V R [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 20];73:409–25. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4560032/pdf/nuv006.pdf.

Zhou D, Yu H, He F, Reilly KH, Zhang J, Li S, et al. Nut consumption in relation to cardiovascular disease risk and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 Jul 20];100:270–7. Available from: http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/100/1/270.full.pdf.

Li TY, Brennan AM, Wedick NM, Mantzoros C, Rifai N, Hu FB. Regular consumption of nuts is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease in women with type 2 diabetes 1,2. J Nutr [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2017 Jul 20];139:1333–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2696988/pdf/nut1391333.pdf.

Ginde AA, Savaser DJ, Camargo CA, Ginde AA. Limited communication and management of emergency department hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2017 Jun 12];4:45–9. Available from: http://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/article/127242/limited-communication-and-management-emergency-department-hyperglycemia.

Okosun IS, Lyn R. Prediabetes awareness, healthcare provider’s advice, and lifestyle changes in American adults. Int J Diabetes Mellitus Int J Diabetes Mellit [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Jun 12];1877–5934. Available from: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijdm.

Bhupathiraju SN, Hu FB. Epidemiology of obesity and diabetes and their cardiovascular complications. Circ Res. 2016;118:1723–35.

Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz GA. Obesity and cancer. Oncologist [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2018 May 7];15:556–65. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20507889.

Dagenais GR, Gerstein HC, Zhang X, McQueen M, Lear S, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Mohan V, Mony P, Gupta R, Kutty VR, Kumar R, Rahman O, Yusoff K, Zatonska K, Oguz A, Rosengren A, Kelishadi R, Yusufali A, Diaz R, Avezum A, Lanas F, Kruger A, Peer N, Chifamba J, Iqbal R, Ismail N, Xiulin B, Jiankang L, Wenqing D, Gejie Y, Rangarajan S, Teo K, Yusuf S Variations in diabetes prevalence in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: results from the Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological study. Diabetes Care [Internet]. American Diabetes Association; 2016 [cited 2018 May 7];39:780–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26965719.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the work of deceased Dr. Rafał Ilow, who actively contributed his experience and knowledge into the work of PURE Poland team (2007–2014).

Study limitations

Food Frequency Questionnaire is an acknowledged method of assessment of nutritional habits and intake of nutritional products but has its limitations. FFQ assesses the intake of nutrients retrospectively and depends entirely on participant’s memory and judgment, which supposedly can contribute to overestimation of consumption of recommended food groups and underestimation of consumption of unrecommended food groups. Categorization of participants into groups of normoglycemia, IFG, and diabetes was made only on the basis of fasting glucose levels (in the case of diabetes, also on self-reported disease and taking glucose-lowering agent). Mentioned methodology could possibly cause some underestimation in IFG and diabetes prevalence (neither hemoglobin A1c was measured nor OGTT was performed), but this is a methodology implemented in the PURE study worldwide [43]. Dietary data was only recorded, and participants did not receive any dietary counseling following the examination.

Funding

The main PURE study and its components are funded by the Population Health Research Institute, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, and through unrestricted grants from several pharmaceutical companies, Poland substudy: Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (grant no. 290/W-PURE/2008/0), Wroclaw Medical University. Additionally, hereby work is funded by Wroclaw Medical University within statutory activity nr ST.C300.17.005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB – manuscript preparation, literature search, manuscript editing

DR –concept and design, manuscript review

KPZ – statistical analysis

MW – data acquisition

AS – manuscript final approval

KZ – concept and design, manuscript review, manuscript guarantor

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All human studies have been reviewed by the appropriate ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in an appropriate version of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki (Positive opinion of bioethical committee of Wroclaw Medical University nr KB-443/2006).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Basiak, A., Różańska, D., Połtyn–Zaradna, K. et al. Comparison of intake of food groups between participants with normoglycemia, impaired fasting glucose, and type 2 diabetes in PURE Poland population. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries 39, 315–324 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-018-0675-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-018-0675-5