Abstract

This paper describes taxonomic position, phylogeny, and phenotypic properties of 14 lactic acid bacteria (LAB) originating from an Apis mellifera guts. Based on the 16S rDNA and recA gene sequence analyses, 12 lactic acid bacteria were assigned to Lactobacillus kunkeei and two others were classified as Fructobacillus fructosus. Biochemically, all isolated lactic acid bacteria showed typical fructophilic features and under anaerobic conditions grew well on fructose, but poorly on glucose. Fast growth of bacteria on glucose was noted in the presence of oxygen or fructose as external electron acceptors. The residents of honeybee guts were classified as heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria. From glucose, they produced almost equimolar amounts of lactic acid, acetic acid, and trace amounts of ethanol. Furthermore, they inhibited the growth of the major honeybee pathogen, Paenibacillus larvae, meaning that the LAB studied may have the health-conferring properties of probiotics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are a heterogeneous group of Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic microorganisms commonly found on flowers and in the intestinal tracts of humans as well as many different animals (Endo et al. 2011; Hammes and Hertel 2006; He et al. 2011; Hove et al. 1999; Neveling et al. 2012). These bacteria, as intestinal microflora, play a crucial role in nutrient assimilation, in modulation of the immune response, and in the mitigation and prevention of divers intestinal disorders (Asama et al. 2015; Evans and Lopez 2004; Gilliland 1990; Jack et al. 1995; Servin 2004). The antimicrobial potential of these bacteria comprises, inter alia, the production of lactic acids, acetic acid (i.e., short–chain–volatile–fatty acids), H2O2, and bacteriocin-like molecules.

An important group of LAB are lactobacilli, classified to the genus Lactobacillus, which are known probiotic microorganisms (Pǎtruicǎ and Mot 2012; Pattabhiramaiah et al. 2012). They are essential for the maintenance of intestinal microbiota homoeostasis and the inhibition of some harmful microorganisms, by production of lactic and acetic acids from lactose and other simple sugars and by the competitive exclusion of pathogens. Lactobacilli disclosed advantageous properties, not only for the health of their hosts, but also for the food industry (Leroy and De Vuyst 2004). Taking into account their advantages, it must be remembered that probiotics should be dedicated to the group of organisms which is planned to be treated and, for example, probiotics suitable for vertebrates are ineffective or even harmful to insects (Ptaszyńska et al. 2015).

Fructophilic LAB (FLAB) are a special group of lactic acid bacteria, which under anaerobic conditions prefer d-fructose as a carbon and energy source, and exhibit very weak growth on glucose (Endo et al. 2009a; Endo et al. 2012; Endo and Okada 2008). They are able to grow well on glucose in the presence of oxygen or when pyruvate and fructose are external electron acceptors. Pentoses are not fermented by fructophilic LAB. Biochemically, FLAB are divided into two groups, i.e., obligately and facultatively fructophilic LAB. Obligately fructophilic lactic acid bacteria convert glucose into almost equimolar amounts of lactic acid and acetic acid and trace amounts of ethanol, i.e., 1:0.9–1.2:0.005–0.01, whereas facultatively fructophylic LAB produce lactic acid, acetic acid, and ethanol at the ratio of 1:1:0.2 (Endo et al. 2010; Endo et al. 2012). Up to now, only two fructophilic Lactobacillus spp. have been identified, i.e., L. kunkeei (Endo et al. 2012) and L. florum (Endo et al. 2010). Obligately fructophilic L. kunkeei bacteria were originally isolated from wine and described by Edwards et al. (1998) and next, from honey, and flowers (Asama et al. 2015; Endo et al. 2011; Neveling et al. 2012). L. florum differs from L. kunkeei in some biochemical properties, and bacteria of this species are defined as facultative fructophiles (Endo et al. 2010). As a facultative fructophilic LAB, one L. brevis strain, i.e., 123–20 was also classified (Neveling et al. 2012). It prefers d-fructose as a carbon and energy source and ferments glucose less efficiently. Glucose dissimilation by this strain is enhanced in the presence of external electron acceptors (i.e., oxygen, d-fructose, and pyruvate). All other fructophilic LAB have been grouped in the genus Fructobacillus, which comprises the following species: Fructobacillus durionis, Fructobacillus fructosus, Fructobacillus ficulneus, and Fructobacillus pseudoficulneus (Endo and Okada 2008). All of them are phylogenetically closely related to bacteria of the genera: Leuconostoc, Oenococcus, and Weissella (Endo and Dicks 2014). Fructophilic LAB have been found in various niches to be rich in fructose (Asama et al. 2015; Chambel et al. 2006; Endo et al. 2009a; Endo et al. 2011; Neveling et al. 2012). Interestingly, FLAB have been also identified in the guts of several insects, including honeybees, whose diet is rich in fructose. The fructophilic lactic acid microbiota of honeybees may play an important role in the health of these insects by the inhibition of pathogens and promotion of carbohydrate digestion (Anderson et al. 2011; Endo and Salminen 2013; Engel et al. 2012). Additionally, such bacteria are potential candidates to be used as honeybee probiotics. Honeybee populations worldwide are still declining mainly due to the presence of different pathogens (e.g., Paenibacillus larvae, Nosema apis, Nosema ceranae, Melissococcus plutonius), the pesticides used, industrial agriculture, and climate change (Anderson et al. 2011; Endo and Salminen 2013; Forsgren et al. 2010; Potts et al. 2010; Ptaszyńska et al. 2013, 2016; Smodiš Škerl et al. 2010). One strategy to reduce the disappearance of honeybee populations may be probiotic lactic acid bacteria used as an alternative to antibiotics to treat and prevent honeybee infections.

The aim of this work was to isolate and phenotypically, as well as genomically, characterize and identify LAB associated with the intestinal tract of honeybees, derived from Poland, in order to better understand the mutual symbiosis between LAB and honeybees.

Materials and methods

Isolation of LAB from the intestinal tracts of honeybee workers

Lactic acid bacteria were isolated from five healthy honeybee families derived from an apiary of the University of Life Sciences, Lublin (Poland). From each colony, 10 honeybees (Apis mellifera) were taken and anesthetized by placing them on ice. Prior to gut dissection, bees were disinfected to remove external microbes with 50% (v/v) ethanol. After that, each honeybee was three times rinsed in sterile purified water. Honeybee guts were removed by pulling the end of the intestine, and the guts isolated from 10 insects, from each family, were homogenized as separate samples, in 1000 μL of sterile 0.85% (w/v) NaCl using a tissue grinder pestle. The obtained homogenate was plated on a de Man–Rogosa Sharpe agar medium (MRS, Oxoid, Basingstoke, the UK) supplemented with 0.5% CaCO3 (w/v), and incubated aerobically in the presence of 5% CO2 at 30 °C for 48–72 h.

Lactic acid bacteria were isolated from healthy honeybees (Apis mellifera) derived from an apiary of the University of Life Sciences, Lublin (Poland). The insects were anesthetized by placing them on ice and surface-disinfected with 50% (v/v) ethanol. Honeybee guts were removed by pulling the end of the intestine and homogenized with a tissue grinder pestle in 100 μL of sterile 0.85% (w/v) NaCl, and the obtained homogenate was plated on a de Man–Rogosa Sharpe agar medium (MRS, Oxoid, Basingstoke, the UK), supplemented with 0.5% CaCO3 (w/v), and incubated aerobically in the presence of 5% CO2 at 30 °C for 48–72 h. Bacterial colonies surrounded by clearance zones (a result of CaCO3 hydrolysis by the produced acids) were selected, purified by streaking onto a MRS agar, and incubated as described above. The isolated bacteria were examined for Gram staining (BioMerieux, Lyon, France) and catalase production. Only Gram-positive and catalase-negative gut isolates were selected and used in further studies. The selected bacteria were propagated in a MRS broth and maintained as frozen stocks at − 20 °C in the presence of 20% (w/v) glycerol and as lyophilized cultures.

Catalase activity

Catalase activity was recorded by the addition of 3% H2O2 on bacteria aerobically growing on a MRS agar as described previously (Endo et al. 2009b).

Bacterial strains, culture media, and growth conditions

In this study, 14 lactic acid bacteria (LAB) isolated from the gastrointestinal tract of honeybees were used. All of them are deposited at the Culture Collection of Mycology Department, M. Curie–Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland, and Polish Collection of Microorganisms, Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Wrocław, Poland. For the antimicrobial assays: Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603, and Paenibacillus larvae LMG 9820 commercially available were used. The first two indicator bacteria were cultivated in a LB broth on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) at 37 °C for 16–18 h (Gibco® LB Broth) and in a LB broth with agar (MERCK), whereas the Paenibacillus larvae LMG 9820 was cultivated in a Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth enriched with vitamin B1 and a BHI agar (Sigma–Aldrich) at similar conditions but in a microaerophilic atmosphere (5% CO2).

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were cultivated in a MRS liquid and solid media (Oxoid, Basingstoke, the UK), a FYP and a GYP broth and agar media composed of (L−1) the following: 10 g of d-fructose (FYP), 10 g of d-glucose (GYP), 10 g of yeast extract, 5 g of polypeptone, 2 g of sodium acetate, 0.5 g of Tween 80, 0.2 g of MgSO4·H2O, 0.01 g of MnSO4·4H2O, 0.01 g of FeSO4·7H2O, 0.01 g of NaCl, and pH 6.8.

The growth of bacteria on d-glucose with external electron acceptors (d-glucose dissimilation) was determined by cultivating bacteria in a GYP broth supplemented with 10 g (L−1) of pyruvate (GYP) or 10 g (L−1) of d-fructose (GYP-F). Cultures were incubated at 30 °C in an anaerobic flask with a gas generating kit (Oxoid™ CO2 Gas Generating Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific™) for 48 h. Utilization of oxygen, as an electron acceptor, was determined for bacteria cultivated in a GYP broth under aerobic conditions (a rotary shaker, 120 rpm) at 30 °C for 72 h. Growth was monitored by measurement of the optical density at 595 nm with a spectrophotometer (Bio–Rad laboratories, Munich, Germany). Anaerobic growth on d-glucose (GYP) and d-fructose (FYP) was determined by the incubation of cultures in flasks with a gas generating kit in the conditions as above, and the growth of bacteria was evaluated by optical density measurement as above.

The production of lactic acid, acetic acid, and ethanol from d-glucose

The production of lactic acid, acetic acid, and ethanol from d-glucose was determined after 7 days of bacteria growth in a GYP broth at 30 °C (on an orbital shaker, at 120 rpm) using HPLC (ProBiotics Polska, Brudzew, Poland) according to Audisio et al. (2011). Cell-free supernatants from bacterial cultures were deproteinized, passed through a 0.22-μm Millex–HV Millipore filter (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA), and analyzed by a HPLC equipped with a Bio–Rad Aminex HPX 87 H column (Bio–Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA) and a refractive index detector. The column temperature was 55 °C, and the flow rate of 5 mM H2SO4 was 0.5 mL/min. Fractions were collected with a Waters 717 Autosampler (Water Corporation, Milford, MA) (Empower 2 software). This analysis was carried out once for each strain.

Sugar tolerance

The sugar tolerance of lactic acid bacteria was determined in a FYP broth containing 10, 20, and 30% d-fructose (w/v). Bacteria were incubated aerobically at 30 °C. Optical density readings (595 nm) of bacterial cultures were recorded over 3 days, using a spectrophotometer (Bio–Rad laboratories, Munich, Germany).

Bacterium temperature and pH growth ranges

Bacterial cultures were grown in a FYP broth (pH 6.8) as described above and 0.1 mL of 48-h-old cultures were added to a 5-mL MRS broth adjusted to pH 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 with 50% H3PO4 and pH 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 using 50% KOH and incubated at 30 °C for 7 days. Bacterial growth was evaluated by measurement of the optical density, at 595 nm using a spectrophotometer (Bio–Rad laboratories, Munich, Germany). Growth of bacteria in the FYP broth (pH 6.8) at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 37, 40, and 45 °C was evaluated for 7 days as described above. Bacteria growth in the conventional FYP broth, pH 6.8 at 30 °C, was used as a control.

Carbohydrate fermentation reactions

Carbohydrate fermentation was recorded using the API 50 CH test (BioMerieux), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bacteria were cultivated at 30 °C, and readings of the test were done every 24 h, for 7 days. This assay was performed once.

Analysis of antibacterial activity of LAB

Antibacterial activities of the cell-free supernatants, from the LAB isolates, against Paenibacillus larvae LMG 9820, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603 were investigated according to Feng et al. (2017) and by the agar spot method (Endo and Salminen 2013). In the first method (Feng et al. 2017), LAB strains were grown on a FYP agar medium at 30 °C for 48 h, as described earlier. The agar containing the bacterial culture was punched using an 8-mm hole puncher and placed into a hole made in a Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar (MERCK) earlier inoculated with 100 μL of the 24-h P. larvae culture as well as into holes made in a LB agar earlier inoculated with 100 μL of a 24 h culture of E.coli or K. pneumoniae. After incubation at 37 °C for 48 h, the plates were examined for the presence, and the diameter of bacterium growth inhibition zones (clear zones) and the average diameters as well as ± SD were calculated based on three independent experiments.

For the agar spot method, 24-h-old LAB cultures in a FYP broth were centrifuged (5000×g, 15 min), and the resulting supernatants were divided into two parts. One of them was adjusted to pH 6.8 by 6 M NaOH; the second one was not neutralized. Next, both the supernatant samples were filtered through 0.2-μm membrane filters and kept at 4 °C until use. Antibacterial activities against indicator bacteria were determined on the same agar media as in the case of the previous method, according to Endo and Salminen (2013). A sterile FYP broth (pH 6.8) served as a control.

Antibacterial activity of the LAB cell-free supernatants was also determined by mixing 4.5 mL of each cell-free supernatant of the lactic acid bacteria (i.e., CH1, CH3, VIII1, and V5 strains) with 500 μL of the indicator bacterium culture (P. larvae LMG 9820, K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603, and E. coli ATCC 25922) prepared as described above (0 h), incubation of these mixtures for 24 h at 37 °C, and estimation of the viable cell count at 0 h and after 24 h. To determine the viable cell count, the bacteria were centrifuged (5000×g, 15 min), washed twice with a 0.7% NaCl solution, and suspended in a 5 mL medium, appropriate to the given bacterium. Next, serial dilutions of the bacterial suspensions were prepared; 100 μL aliquots of dilutions were plated on an agar culture medium (respective to each indicator bacterium), incubated at 37 °C for 48 h, and colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter were calculated. Bacterial cell suspensions at 0 h were used as a control. The survival rate of bacteria was calculated as:

Isolation of genomic DNA

For DNA isolation, bacteria were grown in 5 mL of FYP broth for 24 h at 30 °C. DNA was extracted and purified using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

PCR and sequencing of 16S rDNA

PCR reactions were carried out using genomic DNA isolated as described above. Primers 27F (5′–GAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCA–3′) and 1507R (5′–TACCTTGTTACGACTTCACCCCAG–3′) were used for PCR amplification of almost full-length 16S rDNA of the studied lactic acid bacteria. PCR amplifications were performed in the reaction mixtures (30 μL) containing 6 μL of the DNA sample, 1× PCR buffer (Ready-Mix™ Taq, Sigma), 1× Q solution, 4 mM of MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 0.4 μM of each primer, 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Ready-Mix™ Taq, Sigma). The PCR reactions were carried out at the following temperature profile: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min; 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55.8 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C, and then a final extension of 7 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were analyzed in 2% agarose gel under UV light. The amplified products were purified with the Clean-Up purification columns (A&A Biotechnology) and sequenced from both strands with the BigDye Terminator Cycle sequencing kit using 3500 Genetic Analyzer according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies).

PCR and sequencing of recA gene

The recA gene was amplified using the degenerate primers AmpF: (5′–GCCCTAAAAAARATYGAAAAGAAHTTYGGTAAAGG–3′) and AmpR: (5′–AATGGTGGCGCYACYTTGTTTTTHACAACTTT–3′). The reaction mixture (50 μL) contained 25 μL of Master Mix, 2 μL of each primer, 4 μL of template DNA, and 17 μL of autoclaved, distilled water (Takara–EmeraldAmp® GT PCR Master Mix). The PCR protocol used consisted of the initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min annealing at 50 °C, 1 min extension at 72 °C, and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The amplification products of the expected length of about 730 bp were obtained for all strains tested. The PCR recA gene products were analyzed, purified, and sequenced from both strands with the BigDye Terminator Cycle sequencing kit as described above for the 16S rRNA gene.

Phylogenetic analysis

The obtained 16S rRNA and recA gene sequences were compared to the GenBank nucleotide sequences library, using the BLAST program (Altschul et al. 1990). Both phylogenetic gene sequence analyses were conducted on MEGA 7 software (Kumar et al. 2016) as follows: multiple sequence alignments were constructed and then the resulting alignments were corrected manually. As a result, 1391 and 474 nucleotide positions (bp) were analyzed for the 16S rRNA and recA genes, respectively. A 16S rDNA phylogenetic tree was constructed, using the K2P distance model (Kimura 1980), and a neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm (Saitou and Nei 1987). The maximum likelihood (ML) method was used to reconstruct the genealogy of the recA gene. The jModelTest (Darriba et al. 2012) was used to choose the best-fit evolutionary model for both studied genes. The strength of both tree topologies was verified through 1000 bootstrap replications of the analyzed data. Sequence identity values for 16S rDNA and the recA gene were calculated using BioEdit software (Hall et al. 2011) based on multiple alignments constructed on MEGA 7.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The 16S rDNA and recA gene sequences have been deposited in the GenBank under the accession numbers placed in the phylograms in the parentheses, next to the strain names (Figs. 2 and 3).

Statistical analyses

All experiments were performed in triplicate, unless indicated otherwise. Data from the experiments were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Bonferroni’s procedure. The statistical significance was set at the p < 0.05 confidence level.

Results and discussion

Isolation, phenotypic characterization, and identification of the lactic acid bacteria associated with honeybee guts

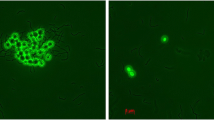

In this paper, we describe lactic acid bacteria isolated from the intestinal tracts of honeybee summer workers. Honeybees were collected in June when bees’ foraging activity is intensive, and the insects accumulate large amounts of a pollen (source of amino acids, mineral elements, and fatty acids) and nectar (a sugar-rich liquid). The MRS agar with 0.5% CaCO3 was used for the isolation of lactic acid bacteria producing organic acids. All of the 14 bacteria isolated were Gram-positive rod cells occurring singly, in pairs or in chains (Online Resources 1(a–c)). Isolated honeybee symbionts grew well under aerobic conditions, in an atmosphere enriched with 5% CO2, and formed on the MRS agar white, smooth, and concave colonies of about 1–2 mm in diameter, after 2 days of incubation at 30 °C, but very tiny colonies (~ 0.1 mm in diameter) on the MRS agar, after incubation for 3 days at 30 °C, under anaerobic conditions (provided by an Oxoid™ CO2 Gas Generating Kit). These characteristics were consistent with those of fructophilic LAB (Endo et al. 2009a, 2012; Neveling et al. 2012). None of the acid-producing isolates, cultured under aerobic conditions, were catalase positive as with the other earlier-described lactic acid bacteria (Endo et al. 2009a; Falsen et al. 1999). The studied honeybee flora grew in a FYP broth (pH 6.8) at 15, 20, 25, 30, 37, and 40 °C. No growth was noted at 5, 10, or 45 °C (Table 1). The optimum temperature for bacterial growth was 30 °C. These bacteria were also screened for pH tolerance properties (Table 1). We found that tolerance to acidic and alkaline pH was very similar among the isolates tested, and all strains grew at pH from 4.0 to 10, with optimum growth at pH 6–8. The optimum growth pH and temperature growth range of the studied honeybee symbionts were very similar to those of L. kunkeei and Fructobacillus sp. bacteria (Endo and Okada 2008; Endo et al. 2012), additionally, supporting the fact that studied Apis mellifera gut isolates are phenotypically very similar to fructophilic lactic acid bacteria. It is necessary to underline that pH changes throughout the adult honeybee alimentary tract. The pH of the social stomach is highly acidic, changes to pH 8 in the midgut, and again decreases in the posterior midgut (Anderson et al. 2011). A low pH in some parts of honeybee gut may inhibit the growth of some pathogens and prevent the genesis of different intestinal diseases.

Carbon source assimilation

In the API 50 CH test, 12 isolates (VI1, VI3, VI4, VI6, VII4, III1, CH1, CH2, CH3, Z1, Z3, and Z5) fermented six of the 49 carbohydrates tested (i.e., glucose, fructose, mannitol, sucrose, trehalose, and gluconate) and produced the acids between 24 and 168 h (Table 1). Acids were produced by all 14 studied LAB from fructose, mannitol, and glucose but fructose was fermented by the bacteria faster than glucose and mannitol. Four isolates (III1, CH3, Z1, and Z5) also fermented ribose, whereas five strains (VI1, CH3, Z1, Z3, and Z5) additionally fermented raffinose. Only two honeybee symbionts (V5 and VIII1) did not metabolize sucrose, trehalose, and potassium gluconate. All other carbon sources that were used in the API 50 CH test, but not mentioned above, were not fermented by any test isolates. Special attention attract V5 and VIII1 strains, which revealed clearly different characteristics in the API 50 CH test than the 12 other studied LAB. Generally, sugar fermentation patterns of the 12 studied honeybee symbionts (VI1, VI3, VI4, VI6, VII4, III1, CH1, CH2, CH3, Z1, Z3, and Z5) were similar to those recorded for the L. kunkeei bacteria, whereas fermentation profiles of two other isolates (V5 and VIII1) resembled those of the F. fructosus strains (Endo et al. 2009a; Endo and Salminen 2013).

Growth characteristics and end products of d-glucose assimilation

To determine the most suitable carbon sources and electron donors for the growth of the studied honeybee symbionts, bacteria were cultivated in a broth containing d-glucose and/or d-fructose under aerobic and anaerobic conditions at 30 °C. Growth was monitored by optical density at 595 nm with a spectrophotometer. The growth profile of the CH1 strain, representing all studied lactic acid bacteria, under different conditions, is presented in Fig. 1. Aerobic growth of the bacteria in a GYP broth, with glucose as a carbon substrate, was comparable with that in a FYP broth containing fructose as a carbon source. Under anaerobic conditions, all tested strains grew well in the FYP broth but poorly in the GYP one. Anaerobic growth of the studied bacteria in the GYP medium, supplemented with 1% fructose, but not in the presence of 1% pyruvate, was similar to that in the FYP broth, suggesting that all these bacteria need fructose as an external electron acceptor for glucose dissimilation, in accordance with the definition of obligately fructophilic acid bacteria (Endo et al. 2009a, 2011). A possible explanation for this phenomenon is the fact that the genus Lactobacillus bacteria have two systems for fructose uptake, i.e., the fructose–phosphotransferase system for the utilization of this sugar as a carbon source and fructose permease for the utilization of fructose as an electron acceptor (Akinterinwa et al. 2008).

The presented data corroborated that the studied lactic acid bacteria, isolated from honeybee guts, are fructophilic organisms preferring fructose as a carbon source and poorly growing on glucose without external electron acceptors (Table 1, Fig. 1). Such fructophilic lactic acid bacteria were identified earlier in fructose-rich niches such as fruits, flowers, wine, honey, beehives, and the intestinal tract of honeybees (Asama et al. 2015; Edwards et al. 1998; Endo et al. 2009a, 2011, 2012; Endo and Salminen 2013; Neveling et al. 2012).

Isolates from the gastrointestinal tract of honeybees were also analyzed for production of organic acids and ethanol from glucose. As determined using GCMS, all strains metabolized glucose and produced large, equimolar amounts of lactic acids and acetic acid as well as small amounts of ethanol. Slight variations between strains were recorded in the production levels of lactic and acetic acids; ethanol was always produced at trace amounts (Table 1). On average, the molar ratios recorded for these three substances produced by the studied bacteria were, 1:1.05:0.07, similar as in the case of obligately fructophilic lactic acid bacteria, including L. kunkeei, F. fructosus, and Fructobacillus pseudoficulneus (Endo and Okada 2008; Endo et al. 2009a, 2012).

Antimicrobial activity of lactic and acetic acids produced by studied honeybee gut residents

Lactic and acetic acids, produced by lactic acid bacteria of honeybees, are known antibacterial substances protecting bees against different pathogens (Audisio et al. 2011; Forsgren et al. 2010). Our results based on the measurement of the bacterium growth inhibition zones indicated that cell-free supernatants of the studied LAB (pH 3.7–4.2) exhibit strong growth inhibition activity against P. larvae LMG 9820, the causative agent of American foulbrood disease, and a lower antibacterial ability against E.coli ATCC 25922 and K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 (the average diameters of the growth inhibition zones were 15.00 ± 0.47 mm, 5.00 ± 0.41 mm, and 5.00 ± 0.22 mm, respectively) (Table 1). These antibacterial activities disappeared after adjustment of the pH supernatant to neutral, indicating that the growth inhibition of indicator strains is related to the organic acids produced by lactic acid bacteria.

The aforementioned antibacterial activities of the cell-free LAB supernatants (diffusive methods) were supported by the analysis of the survival rate of indicator strains being in direct contact with LAB supernatants. All four culture supernatants of the CH1, CH3, VIII1, and V5 strains exhibited similar bactericidal activity against the test bacteria, i.e., killed P. larvae LMG 9820 and K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 bacteria, during 24 h of their contact with the LAB supernatant (0% survival rate, compared to 0 h) and a lower antagonistic activity against E.coli ATCC 25922 (0.02–0.06% survival rate, compared to 0 h). These results point to the possibility of the practical use of isolated lactic acid bacteria as probiotics protecting honeybees against attacks from pathogens.

It is also worth emphasizing that the treatment of hives with organic acids, such as formic, acetic, and lactic acids, is an effective alternative, widely used for many years by beekeepers against mites Varroa sp., fungi Nosema sp., and different bacterial pathogens (Anderson et al. 2011; Maggi et al. 2013; Rosenkranz et al. 2010; VanEngelsdorp et al. 2008).

Fructose tolerance of fructophilic isolates

In the present paper, the fructose tolerance of lactobacilli derived from honeybee guts was determined by analysis of the bacteria’s ability to grow in a FYP broth containing 10, 20, and 30% (w/v) fructose under aerobic conditions for 72 h (Table 1). In the presence of 10% fructose, all strains were multiplied from the beginning to the end of the experiment. At 20 and 30% concentrations of fructose in broth, the bacteria did not grow or their growth was very slow for the first 24 h (OD595 of ~ 0.016–0.764) but all of them, except strains CH2 and VI4, started to multiply/multiplied faster after 24 or 48 h. A similar d-fructose tolerance of fructophilic lactic acid bacteria was documented by Endo et al. (2009a) and Neveling et al. (2012). The ability of isolated fructophilic lactobacilli to tolerate high fructose concentrations may be a beneficial feature, which allows the bacteria to survive during their passage through the honeybee crop containing a large amount of sugar. Additionally, it is worth noting that consumption of fructose (the major component of nectar) by honeybees and the use of this sugar as the main source of carbon and energy favor colonization of the honeybee intestinal tract by fructophilic lactic acetic bacteria. Furthermore, a FYP medium with 20–30% fructose may be a useful tool for the selective isolation of fructophilic LAB.

Molecular identification and phylogeny of studied lactobacilli

For the taxonomic identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from the intestinal tract of adult workers of Apis mellifera, 16S rDNA sequence analysis was carried out. 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis is widely used to define the taxonomic position and for tracing the evolutionary history of prokaryotic microorganisms, including lactic acid bacteria (Alexander et al. 2002; Dellaglio et al. 2005; Endo et al. 2012; Fox et al. 1977; Gnat et al. 2014; Kalita and Małek 2017; Neveling et al. 2012; Pattabhiramaiah et al. 2012). Sequences of nearly full-length 16S rRNA genes (1391 bp) of the 14 studied isolates (VI3, VI4, VI6, VII4, VI1, III1, CH1, CH2, CH3, Z1, Z3, Z5, VIII1, and V5) were determined as was described in “Materials and methods.” The obtained 16S rDNA sequences were aligned, compared with those of other bacteria available in the GenBank library, and the evolutionary distances between studied honeybee symbionts and the reference lactic acid bacteria were calculated. Phylogeny of the investigated isolates, reconstructed with NJ method, is presented in the phylogram (Fig. 2). The results from comparative 16S rDNA sequences confirmed those from analysis of the phenotypic properties. On the 16S rDNA phylogram, 12 of the 14 strains studied (VI3, VI4, VI6, VII4, VI1, III1, CH1, CH2, CH3, Z1, Z3, and Z5) were clustered together with L. kunkeei bacteria, with high confidence (99% bootstrap—BS) and the two remaining strains (VIII1 and V5) were grouped with Fructobacillus fructosus reference strains in 99% of bootstrap replicates (Fig. 2). The 16S rDNA sequences of nine investigated honeybee symbionts from the L. kunkeei cluster (i.e., VI3, VI4, VI1, III1, CH1, CH2, Z1, Z3, and Z5) matched perfectly with each other (100% sequence identity), and they differed from other three isolates belonging to this cluster (i.e., VI6, VII4, and CH3) in only 1–2 nucleotides per 1391 ones. The 16S rDNA sequences of the 12 studied bacteria matched very well to L. kunkeei 16S rDNA sequences (99.6–100% nucleotide identity) and showed far fewer identical base pairs with 16S rDNA sequences of the other reference bacterial species of the genus Lactobacillus, Pedicoccus sp., Leuconostoc sp., and Fructobacillus sp. (including in this latter group two studied honeybee isolates (VIII1 and V5) closely related to fructobacilli), i.e., 88.7–97.4%, 93.9–94.3%, 85.8–86.8%, and 85.9–86.2%. The 16S rDNA sequences of the two test bacteria from the F. fructosus clade (VIII1 and V5) shared 99.9% identical nucleotides. They were phylogenetically close to the reference F. fructosus and Fructobacillus durionis strains with a 16S rDNA nucleotide identity of 98.9–100% and 97.8–97.9%, respectively, and all these strains formed in the 16S rRNA gene tree monophyletic cluster with high confidence (99% BS). On the sister branch to fructobacilli, the genus Leuconostoc strains were located (Fig. 2). Both these bacterium clusters, with a 16S rDNA sequence similarity of 93.2–93.7%, constituted one lineage, on the outskirt of the phylogram.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree showing the phylogenetic relationships of fructophilic lactic acid bacteria isolated from Apis mellifera gut (in bold) to closely related taxa based on nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences. The GenBank accession number for each strain is shown in parentheses. Bootstrap values (based on 100 replicates) greater than 70% are indicated at the branching points. The scale bar presents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site

It is worth pointing out that currently, there is no guideline acceptable by all taxonomists, for classification of bacteria to genus and species, although since 1980, the 16S rRNA gene has been commonly used for taxonomic studies as a ubiquitous and highly conserved molecular marker (Rosselló-Mora and Amann 2001; Stackebrandt and Ebers 2006; Stackebrandt and Goebel 1994; Yarza et al. 2014). Ninety-five percent and higher 16S rDNA sequence conservation served as a “gold standard” for bacteria classification to the genus and two strains with a 16S rDNA sequence similarity lower than 97% were considered as belonging to a distinct species (Rosselló-Mora and Amann 2001; Stackebrandt and Goebel 1994). There are also suggestions that 99% sequence identity of a small subunit rRNA gene is a suitable cutoff value for bacteria classification to species, whereas 97% sequence similarity of these genes is a proper threshold for the definition of genus members (Drancourt et al. 2000). In 2006, the cutoff value of 16S rDNA sequence similarity for species designation was re-evaluated at 98.7% (Stackebrandt and Ebers 2006). There is also documented evidence that aforementioned threshold values for 16S rDNA sequences do not apply to some genera, e.g., interspecies 16S rDNA sequence similarity between Clostridium botulinum and Clostridium sporogenes was 99.7%, whereas in the genus Streptomyces, the lowest noted interspecies 16S rDNA sequence identity was 78% (Alexander et al. 2002; Olsen et al. 1995). Such differences in the cutoff values of 16S rDNAs may result from their different evolutionary speed, in different bacteria.

Although the 16S rRNA gene is an effective molecular marker in bacterial taxonomy and phylogeny, its use as a sole indicator of bacteria relatedness has been criticized, mainly due to low resolution of 16S rDNA sequences at the species and some genus levels (Cooper and Feil 2004; Janda and Abbott 2006). To resolve this issue and evaluate the reliability of taxonomic conclusions drawn from the 16S rDNA sequence analysis of lactic acid bacteria isolated from honeybee guts, comparative sequence analysis of the recombinase A encoding gene (recA), with a generally higher resolution than that of the 16S rRNA gene, was undertaken.

The results from comparative sequence analysis of the 474-bp long fragment of the recA gene of eight representative honeybee isolates (VI3, VII4, VI1, III1, CH3, CH1, Z3, and Z5), belonging to Lactobacllus kunkeei clade in the 16S rDNA tree and two other honeybee symbionts (VIII1 and V5) from the Fructobacillus fructosus cluster confirmed results based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. As expected, the recA gene sequences of eight strains (VI3, VII4, VI1, III1, CH3, CH1, Z3, and Z5), with 98.9–100% sequence identity to one another, were most closely related to recA sequences of the L. kunkeei strains (98.5–100% invariant nucleotides). Their similarities to the recA sequences of other Lactobacillus species, Pedicoccus sp., Leuconostoc sp., Fructobacillus fructosus (including into this group honeybee isolates VIII1 and V5), and Fructobacillus species other than F. fructosus were 76.7–82.4, 79.3–80.3, 71.3–73.8, 71.0–71.9, and 70.6–74.2%, respectively.

The recA sequences of two other studied honeybee gut isolates (VIII1 and V5) perfectly matched each other (100% sequence identity) and shared 99.3–100% identical nucleotides with the recA gene of their closest relatives, i.e., the F. fructosus strains. The pairwise recA sequence similarities between VIII1, V5 honeybee symbionts, and the Fructobacillus species (other than F. fructosus), Leuconostoc sp., Pedicoccus sp., L. kunkeei strains, and other species of the genus Lactobacillus were 82.0–85.6, 76.3–80.5, 71.7–73.6, 71.0–72.1, and 70.4–76.1%, respectively. In the recA gene phylogram, based on the 474-bp sequences, eight studied strains (VI3, VII4, VI1, III1, CH3, CH1, Z3, and Z5) were grouped together with L. kunkeei in a highly supported (100% BS) monophyletic clade (Fig. 3). In the vicinity of this clade, Lactobacillus species other than L. kunkeei and Pedicoccus sp. were located. On the outside of all these bacteria, on the outskirt of the recA tree, VIII1 and V5 honeybee isolates, forming a tight, robust cluster with the F. fructosus strains, were positioned. Their close neighbors were the Fructobacillus species other than F. fructosus and the Leuconostoc species. All these bacteria occupied a common lineage on the recA gene tree and formed two highly supported subclusters (Fig. 3). The comparative analysis of the recA gene sequences of honeybee lactic acid bacteria provided independent evidence that the eight studied LAB, VI3, VII4, VI1, III1, CH3, CH1, Z3, and Z5, are phylogenetically closely related to L. kunkeei and belong to this species, whereas two other honeybee isolates, VIII1 and V5, share a common ancestor with F. fructosus and are members of this species.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree showing the phylogenetic relationships of fructophilic lactic acid bacteria isolated from Apis mellifera gut (in bold) to closely related taxa based on partial recA gene sequences. The GenBank accession number for each strain is shown in parentheses. Bootstrap values (based on 100 replicates) greater than 70% are indicated at the branching points. The scale bar presents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site

In conclusion, the data presented in this paper concerning the 16S rDNA and recA gene sequence analyses of lactic acid bacteria inhabiting the Apis mellifera intestinal tract as well as phenotypic properties of these bacteria showed that the studied honeybee gut residents are obligately fructophilic lactic acid bacteria belonging to the L. kunkeei and F. fructosus species. The presented studies also suggest that isolated lactic acid bacteria may be good candidates for potential application as probiotics, protecting honeybees against pathogens (e.g., P. larvae) and maintaining honeybee colonies in good health.

References

Akinterinwa O, Khankal R, Cirino PC (2008) Metabolic engineering for bioproduction of sugar alcohols. Curr Opin Biotechnol 19:461–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2008.08.002

Alexander B, Andersen JH, Cox RP, Imhoff JF (2002) Phylogeny of green sulfur bacteria on the basis of gene sequences of 16S rRNA and of the Fenna-Matthews-Olson protein. Arch Microbiol 178:131–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-002-0432-4

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Anderson KE, Sheehan TH, Eckholm BJ, Mott BM, DeGrandi-Hoffman G (2011) An emerging paradigm of colony health: microbial balance of the honey bee and hive (Apis mellifera). Insect Soc 58:431–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-011-0194-6

Asama T, Arima TH, Gomi T, Keishi T, Tani H, Kimura Y, Tatefuji T, Hashimoto K (2015) Lactobacillus kunkeei YB38 from honeybee products enhances IgA production in healthy adults. J Appl Microbiol 119:818–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.12889

Audisio M, Torres MJ, Sabaté DC, Ibarguren C, Apella MC (2011) Properties of different lactic acid bacteria isolated from Apis mellifera L. bee-gut. Microbiol Res 166:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2010.01.003

Chambel L, Chelo IM, Zé-Zé L, Pedro LG, Santos MA, Tenreiro R (2006) Leuconostoc pseudoficulneum sp. nov., isolated from a ripe fig. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 56:1375–1381. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.64054-0

Cooper JE, Feil EJ (2004) Multilocus sequence typing-what is resolved? Trends Microbiol 12:373–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2004.06.003

Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D (2012) JModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods 9:772–775. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2109

Dellaglio F, Felis GE, Castioni A, Torriani S, Germond JE (2005) Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. indicus subsp. nov., isolated from Indian dairy products. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 55:401–404. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.63067-0

Drancourt M, Bollet C, Carlioz A, Martelin R, Gayral JP, Raoult D (2000) 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis of a large collection of environmental and clinical unidentifiable bacterial isolates. J Clin Microbiol 38:3623–3630. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0504930102

Edwards CG, Haag KM, Collins MD, Hutson RA, Huang YC (1998) Lactobacillus kunkeei sp. nov.: a spoilage organism associated with grape juice fermentations. J Appl Microbiol 84:698–702. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00399.x

Endo A, Dicks LMT (2014) Physiology of the LAB. In: Wood B, Holzapfel WH (eds) Lactic acid bacteria. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, pp 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118655252.ch2

Endo A, Okada S (2008) Reclassification of the genus Leuconostoc and proposals of Fructobacillus fructosus gen. nov., comb. nov., Fructobacillus durionis comb. nov., Fructobacillus ficulneus comb. nov. and Fructobacillus pseudoficulneus comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58:2195–2205. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.65609-0

Endo A, Salminen S (2013) Honeybees and beehives are rich sources for fructophilic lactic acid bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol 36:444–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.syapm.2013.06.002

Endo A, Futagawa-Endo Y, Dicks LMT (2009a) Isolation and characterization of fructophilic lactic acid bacteria from fructose-rich niches. Syst Appl Microbiol 32:593–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.syapm.2009.08.002

Endo A, Futagawa-Endo Y, Kawasaki S, Dicks LMT, Niimura Y, Okada S (2009b) Sodium acetate enhances hydrogen peroxide production in Weissella cibaria. Lett Appl Microbiol 49:136–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02633.x

Endo A, Futagawa-Endo Y, Sakamoto M, Kitahara M, Dicks LMT (2010) Lactobacillus florum sp. nov., a fructophilic species isolated from flowers. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60:2478–2482. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.019067-0

Endo A, Irisawa T, Futagawa-Endo Y, Sonomoto K, Itoh K, Takano K, Okada S, Dicks LMT (2011) Fructobacillus tropaeoli sp. nov., a fructophilic lactic acid bacterium isolated from a flower. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 61:898–902. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.023838-0

Endo A, Irisawa T, Futagawa-Endo Y, Takano K, du Toit M, Okada S, Dicks LMT (2012) Characterization and emended description of Lactobacillus kunkeei as a fructophilic lactic acid bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 62:500–504. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.031054-0

Engel P, Martinson VG, Moran NA (2012) Functional diversity within the simple gut microbiota of the honey bee. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:11002–11007. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1202970109

Evans JD, Lopez DL (2004) Bacterial probiotics induce an immune response in the honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J Econ Entomol 97:752–756. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/97.3.752

Falsen E, Pascual C, Sjödén B, Ohlén M, Collins MD (1999) Phenotypic and phylogenetic characterization of a novel Lactobacillus species from human sources: description of Lactobacillus iners sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 49:217–221. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-49-1-217

Feng Y, Qiao L, Liu R, Yao H, Gao C (2017) Potential probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from the intestinal mucosa of healthy piglets. Ann Microbiol 67:239–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13213-017-1254-6

Forsgren E, Olofsson TC, Vasquez A, Fries I, Vásquez A, Fries I (2010) Novel lactic acid bacteria inhibiting Paenibacillus larvae in honey bee larvae. Apidologie 41:99–108. doi. https://doi.org/10.1051/Apido/2009065

Fox GE, Magrum LJ, Balch WE, Wolfe RS, Woese CR (1977) Classification of methanogenic bacteria by 16S ribosomal RNA characterization. Proc Natl Acad Sci 74:4537–4541. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.74.10.4537

Gilliland SE (1990) Health and nutritional benefits from lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett 87:175–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04887.x

Gnat S, Wójcik M, Wdowiak-Wróbel S, Kalita M, Ptaszyńska A, Małek W (2014) Phenotypic characterization of Astragalus glycyphyllos symbionts and their phylogeny based on the 16S rDNA sequences and RFLP of 16S rRNA gene. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Int J Gen Mol Microbiol 105:1033–1048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-014-0163-y

Hall T, Biosciences I, Carlsbad C (2011) BioEdit: an important software for molecular biology. GERF Bull Biosci 2:60–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.24632

Hammes WP, Hertel C (2006) The genera Lactobacillus and Carnobacterium. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E (eds) The prokaryotes. Springer, New York, pp 320–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-30744-3_10

He H, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Wei C (2011) Bacteria Associated with Gut Lumen of Camponotus japonicus Mayr Environ Entomol 40:1405–1409. https://doi.org/10.1603/EN11157

Hove H, Nørgaard H, Mortensen PB (1999) Lactic acid bacteria and the human gastrointestinal tract. Eur J Clin Nutr 53:339–350

Jack RW, Tagg JR, Ray B (1995) Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Rev 9:171–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s101230100003

Janda JM, Abbott SL (2006) The enterobacteria, second edition. Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555817541

Kalita M, Małek W (2017) Molecular phylogeny of Bradyrhizobium bacteria isolated from root nodules of tribe Genisteae plants growing in southeast Poland. Syst Appl Microbiol 40:482–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.syapm.2017.09.001

Kimura M (1980) A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 16:111–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01731581

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054

Leroy F, De Vuyst L (2004) Lactic acid bacteria as functional starter cultures for the food fermentation industry. Trends Food Sci Technol 15:67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2003.09.004

Maggi M, Negri P, Plischuk S, Szawarski N, De Piano F, De Feudis L, Eguaras M, Audisio C (2013) Effects of the organic acids produced by a lactic acid bacterium in Apis mellifera colony development, Nosema ceranae control and fumagillin efficiency. Vet Microbiol 167:474–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.07.030

Neveling DP, Endo A, Dicks LMT (2012) Fructophilic Lactobacillus kunkeei and Lactobacillus brevis isolated from fresh flowers, bees and bee-hives. Curr Microbiol 65:507–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-012-0186-4

Olsen I, Johnson JL, Moore LVH, Moore WEC (1995) Rejection of Clostridium putrificum and conservation of Clostridium botulinum and Clostridium sporogenes request for an opinion. Int J Syst Bacteriol 45:414. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-45-2-414

Pǎtruicǎ S, Mot D (2012) The effect of using prebiotic and probiotic products on intestinal micro-flora of the honeybee (Apis mellifer carpatica). Bull Entomol Res 102:619–623. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485312000144

Pattabhiramaiah M, Reddy MS, Brueckner D (2012) Detection of novel probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus spp. in the workers of Indian honeybee, Apis cerana indica. Int J Environ Sci 3:1135–1143. https://doi.org/10.6088/ijes.00202030002

Potts SG, Biesmeijer JC, Kremen C, Neumann P, Schweiger O, Kunin WE (2010) Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol Evol 25:345–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007

Ptaszyńska AA, Grzegorz G, Mułenko W, Olszewski K (2013) Impact of ethanol on Nosema spp. infected bees. Med Weter 69:736–741

Ptaszyńska AA, Borsuk G, Zdybicka-Barabas A, Cytryńska M, Małek W (2015) Are commercial probiotics and prebiotics effective in the treatment and prevention of honeybee nosemosis C? Parasitol Res 115:397–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-4761-z

Ptaszyńska AA, Paleolog J, Borsuk G (2016) Nosema ceranae infection promotes proliferation of yeasts in honey bee intestines. PLoS One 11:e0164477. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164477

Rosenkranz P, Aumeier P, Ziegelmann B (2010) Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J Invertebr Pathol 103:96–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2009.07.016

Rosselló-Mora R, Amann R (2001) The species concept for prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol Rev 25:39–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00571.x

Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425

Servin AL (2004) Antagonistic activities of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria against microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev 28:405–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsre.2004.01.003

Smodiš Škerl MI, Kmecl V, Gregorc A (2010) Exposure to pesticides at sublethal level and their distribution within a honey bee (Apis mellifera) colony. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 85:125–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-010-0069-y

Stackebrandt E, Ebers J (2006) Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol Today 8:6–9

Stackebrandt E, Goebel BM (1994) Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 44:846–849. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-44-4-846

VanEngelsdorp D, Underwood RM, Cox-Foster DL (2008) Short-term fumigation of honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colonies with formic and acetic acids for the control of Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae). J Econ Entomol 101:256–264. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493(2008)101[256:SFOHBH]2.0.CO;2

Yarza P, Yilmaz P, Pruesse E, Glöckner FO, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB, Euzéby J, Amann R, Rosselló-Móra R (2014) Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:635–645. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3330

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the president of Biowet Puławy DVM Mirosław Grzęda for valuable discussions and advice regarding the treatment of a patent bacterial strains. All studied bacterial strains are protected under the patent application no. P423363.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

For this type of studies on honeybees, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Communicated by: Agnieszka Szalewska-Palasz

Electronic supplementary material

Online Resource 1

(a-c) A light microscopic images of Gram stained lactic acid bacteria isolated from Apis mellifera intestinal tract (JPG 747 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pachla, A., Wicha, M., Ptaszyńska, A.A. et al. The molecular and phenotypic characterization of fructophilic lactic acid bacteria isolated from the guts of Apis mellifera L. derived from a Polish apiary. J Appl Genetics 59, 503–514 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13353-018-0467-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13353-018-0467-0