Abstract

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3), also known as Machado–Joseph disease (MJD), is a neurodegenerative disorder caused by a polyglutamine expansion in the ATXN3 gene. In spite of the identification of a clear monogenic cause 25 years ago, the pathological process still puzzles researchers, impairing prospects for an effective therapy. Here, we propose the disruption of protein homeostasis as the hub of SCA3 pathogenesis, being the molecular mechanisms and cellular pathways that are deregulated in SCA3 downstream consequences of the misfolding and aggregation of ATXN3. Moreover, we attempt to provide a realistic perspective on how the translational/clinical research in SCA3 should evolve. This was based on molecular findings, clinical and epidemiological characteristics, studies of proposed treatments in other conditions, and how that information is essential for their (re-)application in SCA3. This review thus aims i) to critically evaluate the current state of research on SCA3, from fundamental to translational and clinical perspectives; ii) to bring up the current key questions that remain unanswered in this disorder; and iii) to provide a frame on how those answers should be pursued.

Similar content being viewed by others

Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3 or Machado–Joseph Disease: Etiology, Clinical, and Neuropathological features

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3) or Machado–Joseph disease (MJD) is a hereditary neurodegenerative disease, with autosomal dominant transmission [1]. SCA3 is caused by an unstable expansion of the cytosine-adenine-guanidine (CAG) trinucleotide within the coding region of the ATXN3 gene, mapped to chromosome 14q32.1 [2, 3]. The CAG repeat number ranges from 10 to 44 in normal individuals, whereas in SCA3 patients, the CAG size repeat is described to vary from 61 to 87; repeats between 45 and 60 are associated with incomplete phenotype penetrance [3]. In patients, there is a negative correlation between the age at disease onset and the number of CAG repeats [4]. The mutated ATXN3 gene is translated into an abnormal polyglutamine (polyQ) tract within the ataxin-3 (ATXN3) protein, which has normal expression levels even in the presence of this mutation [5].

There is clinical heterogeneity among SCA3 patients, which resulted in the definition of at least 4 disease subtypes, according to their phenotypic presentation [6, 7]. The main clinical hallmark of SCA3 is progressive ataxia, a motor coordination dysfunction that affects gait, balance, speech, and gaze. SCA3 is also characterized by dysfunction of the pyramidal tract, manifesting as spasticity and hyperreflexia, which is variably associated with peripheral muscular atrophy and/or other motor-related clinical manifestations such as parkinsonism, dysarthria, nystagmus, dystonia, and external progressive ophthalmoplegia. Nonmotor symptoms are less severe but include sleep, cognitive, and psychiatric disturbances [1, 6, 8,9,10,11,12,13].

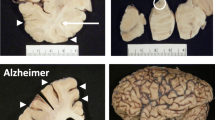

The diversity of symptoms and clinical heterogeneity of SCA3 patients reflects the pattern of central nervous system (CNS) cell degeneration. Multiple neuronal systems are affected, including the cerebellum, the brainstem and some cranial nerves, the basal ganglia, and the spinal cord [11, 14]. Neurodegeneration occurs within the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum with relative preservation of the Purkinje cells of the cerebellar cortex when compared to other ataxias. However, the loss of granule and of Purkinje cells was reported in the cerebellar vermis. Neurodegeneration also targets the vestibular, pontine, and motor nuclei of the brainstem, as well as subregions of the basal ganglia including the globus pallidus, subthalamic nuclei, and the substantia nigra. The nerve motor nuclei, Clarke’s column nuclei, and the anterior horn of the spinal cord are also affected. No significant degeneration has classically been described in the cerebral cortex and in the striatum, although more recent findings gainsay the first neuropathological descriptions [8, 11, 15,16,17,18,19,20]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies most commonly detect abnormalities of the basal ganglia (such as atrophy of the globus pallidus), pontocerebellar atrophy (of the pons and superior and middle cerebellar peduncles), and dilation of the 4th ventricle [21, 22].

The most relevant neuropathological feature of SCA3 is the presence of intraneuronal inclusions of mutant ATXN3 proteins in postmortem patient brains, as a consequence of the change in conformation of ATXN3 due to the expanded polyQ tract. Intriguingly, these inclusions were detected within brain regions described to be affected by neurodegeneration but also in regions that are typically spared in this disease [23,24,25]. In addition, thalamic neurodegeneration was reported to occur independent of the detection of mutant ATXN3 immunopositive neuronal intranuclear inclusions [26]. At first, these findings may appear contradictory as they seem to point to a pleiotropic role of these inclusions: either unspecific, pathognomonic, or even protective role, as they may serve as a cellular reservoir for retaining the pathogenic expanded protein. In the latter conceptual model, the observed toxicity is attributed to soluble oligomers that precede inclusion body formation in the aggregation process [27, 28]. However, it could be just that there is a cellular- and temporal-specific regulation of the aggregation process in which the appearance of the visible inclusions of mutant ATXN3 precedes toxicity and neuronal death in some cells, whereas in others, the bigger aggregates are never formed as toxicity surpasses aggregation. In addition, it is possible that in spared brain regions, the aggregation process is assisted and controlled by cellular-specific quality control mechanisms in such a way that toxicity is maintained subthreshold, avoiding cell dysfunction and death.

The cell-specific toxic outcome of the ubiquitously expressed aggregation-prone expanded protein could also be a reflex of its subcellular localization. Mutant ataxin-3 aggregates are mostly described to be intranuclear. However, they were also found in the cytoplasm and within the axons of the fiber tracts known to undergo neurodegeneration in this disease [29,30,31]. Similar to neuronal nuclear inclusions, the axonal ATXN3 aggregates were ubiquitinated and immunopositive for the proteasome and autophagy-associated shuttle protein p62 [23, 30], strengthening the involvement of neuronal protein quality control (PQC) mechanisms in the management of this mutant protein.

In the next section, we will explore the mechanisms of SCA3 pathogenesis, placing the aggregation features of ATXN3 as the initiating factors of disease. We will first describe how the polyQ expansion impacts not only the function of ATXN3 but also neuronal PQC mechanisms. Then, we provide extensive descriptions of the various cellular processes that are consequently affected by the mutation. Finally, we detail how ATXN3 aggregation can also have an important non-cell autonomous impact.

Mechanism of SCA3 Pathogenesis

Many molecular mechanisms and cellular pathways have been implicated in SCA3 pathogenesis. Here, we propose the misfolding of the mutant ATXN3 protein and the subsequent aggregation process, with eventual deposition of insoluble intracellular aggregates, to be the hub of the pathogenic process, and discuss how protein dyshomeostasis impacts key cellular pathways causing dysfunction and disease (Fig. 1).

Overview of the molecular pathogenesis of SCA3. An expansion of CAG repeats (above 60) in exon 10 of the ATXN3 gene is the underlying cause of SCA3. The translated protein therefore harbors an expanded polyglutamine stretch, between 2 UIMs. This expansion leads to misfolding of ATXN3, consequent oligomerization and accumulation of the abnormal protein in amorphous aggregates or amyloid fibers, which can be visualized as intracellular inclusions by immunohistochemistry. These changes consequently affect protein homeostasis, through a probable loss of deubiquitylase activity, impact in aggresomes, autophagy, the ERAD, and the proteasome. The loss of proteostasis has several consequences in cellular physiology, impacting the nucleus (namely misfolding of nuclear proteins, DNA damage, and changes in transcription), the mitochondria (through abnormal interaction with several mitochondrial proteins, stress of misfolded proteins, as well as a decrease in mitochondrial DNA), the ER (through the ERAD and induction of intracellular Ca2+ release), and cellular communication (through potential impairment of axonal transport and synaptic vesicle release). ATXN3 = ataxin-3; ER = endoplasmic reticulum; ERAD = endoplasmic reticulum–associated protein degradation; NES = nuclear export signal; NLS = nuclear localization sequence; TF = transcription factors; Ub = ubiquitin; UIM = ubiquitin-interacting motives

Disruption of Protein Homeostasis Is the Initiating Factor of Pathogenesis

Proteins are the main cellular effectors, with native protein conformation and proper dynamic responses being critical for their biological function. Moreover, the abundance of each protein within the proteome of each cell must be tightly controlled to avoid abnormal (self-) interactions and protein aggregation. In fact, this state of a balanced proteome or of protein homeostasis (a.k.a. proteostasis) is ensured by an extensive network of molecular chaperones, proteolytic systems, and their regulators, which include approximately 2000 proteins in a human cell [32, 33], which composes the PQC network. This network i) assists in the folding of newly synthetized proteins; ii) serves to safeguard that correctly folded proteins are generated at the correct time, cellular location, and stoichiometry to allow assembly of oligomeric protein complexes; iii) prevents proteins from misfolding and aggregating; and (iv) orchestrates folding, disaggregation, and degradation machineries (autophagy or proteasome-mediated degradation) to ensure that misfolded proteins are either refolded or removed, if permanently misfolded or superfluous. These mechanisms avoid the accumulation of damaged/dysfunctional proteins and of protein aggregates, which can reach a toxicity threshold when proteostasis is impaired [34, 35].

The presence of mutations within the genome which increases aggregation propensity constitutes an endogenous stress to neuronal cells and challenges their homeostasis. During the aggregation process, folding intermediates and misfolded states of the proteins likely accumulate, and the intermolecular contacts between non-native states result in the formation of various aggregate species, including oligomers, amorphous aggregates, and amyloid fibrils. Amyloid fibrils are often thermodynamically more stable than the native state, favoring their formation. Components of the PQC network, including molecular chaperones, contribute to enhance on-pathway reactions that support progression of the misfolded intermediates towards the native state and block off-pathway reactions that lead to misfolding and aggregation [36]. The current understanding of ATXN3 folding, self-assembly, and aggregation comes mainly from in vitro studies (reviewed in [37]). A 2-step model has been proposed: the first step of ATXN3 self-assembly, common to WT and polyQ-expanded ATXN3, is centered on the N-terminal Josephin domain. The oligomers and small protofibrils formed are sensitive to SDS and can be recognized by the anti-oligomer-specific antibody A11. Importantly, however, this step occurs faster in expanded forms of ATXN3. The second step in ATXN3 aggregation, exclusively dependent on the polyQ expansion, leads to the generation of mature and SDS-resistant ATXN3 fibrils [38,39,40,41].

It has been proposed that a toxic C-terminal fragment containing the polyQ segment of ATXN3 would be required for pathology and constitutes the trigger of the aggregation process [42,43,44]. Accordingly, mutant ATXN3 was shown to be a substrate of caspases. However, caspase inhibitors were unable to stop fragment formation, suggesting the involvement of other enzymes [44,45,46,47]. Calpains were also found to play a role in ATXN3 proteolysis in cell culture, including in l-glutamate-induced excitation of patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)–derived neurons [48,49,50]. In these models, the formation of SDS-insoluble aggregates was induced by calcium-dependent proteolysis of ATXN3, a process abolished by calpain inhibition (reviewed in [51]). This evidence was strengthened by studies in vivo in which manipulation of calpastatin levels, an endogenous calpain inhibitor, led to modulation of the neurological phenotype seen in a SCA3 mouse model, as well as of mutant ATXN3 aggregation and neurodegeneration, consistent with a role for calpain activation in pathogenesis [50, 52]. Calpastatin depletion in the postmortem dentate nucleus of SCA3 patients [52] further supported these observations. In addition to their role in ATXN3 cleavage, it is possible that the downstream consequences of ATXN3 aggregation, such as activation of cell death processes, are also mitigated by calpain inhibition. If this is the case, the toxicity caused by the expression of mutant ATXN3 fragment proteins should also be mitigated by calpain inhibition or calpastatin overexpression. In contrast, if the calpain inhibitors are targeting mainly ATXN3 cleavage, they should be ineffective in SCA3 disease models expressing cleaved ATXN3 to start with. In order to distinguish cleavage-dependent and independent effects in SCA3 pathology, there is an urgent need for novel methodologies that enable the visualization of protein aggregates in living brains and allow effective discrimination of the triggers of nucleation, which could be achieved by developing radiotracers for positron emission tomography (PET) or similar procedure.

Independent of the species that triggers aggregation, it is generally accepted that a gain-of-function toxicity of the expanded ATXN3 protein contributes highly to SCA3 pathology. This toxicity is largely attributed to the aberrant association of PQC network components and other metastable proteins with these aggregates, including molecular chaperones, ubiquitin conjugates, proteasome subunits, the transcription coactivator cAMP response element–binding protein (CREB)–binding protein (CBP), the ATPase valosin–containing protein (VCP)/p97, and nonexpanded wild-type ATXN3 [53,54,55,56,57,58]. Some of these interactions, such as those between polyQ-containing protein aggregates and proteasomal subunits, appear irreversible, suggesting a permanent sequestration of these proteins. On the other hand, the association with molecular chaperones seems to be transient, suggesting that chaperones may be functionally recognizing aggregates as substrates for potential disaggregation and/or refolding [59, 60]. Beyond refolding of toxic misfolded proteins, chaperones are also essential for the folding of a large number of so-called “client” proteins, regulating a wide range of essential cellular processes, including gene expression, vesicular trafficking, and signal transduction [61,62,63]. This led some authors to propose a chaperone competition model, in which aggregates, client, and metastable proteins (polyQ, huntingtin, ATXN1, and superoxide dismutase-1) rival for finite chaperone resources [64]. Two examples are the impairment of clathrin-mediated endocytosis and of nuclear protein degradation, due to polyQ-mediated sequestration of the highly abundant major chaperone heat shock cognate protein 70 (HSC70) and of a low-abundance cochaperone, Sis1p/DNAJB1, respectively [64, 65]. This shortcoming in folding resources may trigger neuronal dysfunction and disease onset [66]. In vivo corroboration of these findings is still missing for ATXN3 and for other metastable proteins.

Beyond the recruitment of proteasome subunits into the aggregates, ATXN3 misfolding can also impact protein degradation due to its direct role in the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) [57, 67, 68]. The protein domains of ATXN3 include an N-terminal Josephin domain with deubiquitylase activity and a C-terminal region bearing 2 or 3 ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs) neighboring the polyQ tract, of still unknown function. It has been proposed that ATXN3 contributes to facilitate the proteasomal degradation of ubiquitylated proteins by editing polyubiquitin chains of a subset of substrates prior to digestion [69] and to protect others from degradation [70,71,72]. Although in vitro studies with artificial substrates failed to show an impact of the expansion of the polyQ segment of ATXN3 on its DUB activity [37, 73, 74], the insolubility and immobile nature of the inclusions in vivo [75] may make mutant ATXN3 less prompt to locate at the sites at which editing of Ub chains is needed. Moreover, the expanded polyQ of ATXN3 can differentially interact with UPS components and interfere with the degradation of its proteolytic substrates [67, 76, 77]. On the other hand, accumulation of misfolded proteins per se was shown to directly inhibit the proteasome activity [78], exacerbating these toxic effects. In fact, ATXN3 itself can be degraded by the proteasome and its polyQ expansion was proposed to inhibit the proteasome [79]. Some chaperones and UPS components were reported to modulate ATXN3 degradation, including the ubiquitin E3 ligase parkin, Hsp70, the ubiquitin assembly factor E4B, the cochaperone C-terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP), and the Rad23A/B proteins [79,80,81,82], consistent with a positive role of facilitating mutant ATXN3 degradation in pathogenesis.

It has been proposed that ATXN3 is also degraded through autophagy [83], being the mutant (soluble) protein more prone to autophagic degradation, as no changes in endogenous wild-type ATXN3 levels were observed in drug-induced autophagy activation in vivo [84]. This, however, somehow contradicts the similar steady-state levels of WT and mutant ATXN3 proteins that are usually found across different model systems. Importantly, a normal function for polyQ tracts in autophagy was suggested. The polyQ domain enables wild-type ATXN3 to interact with beclin-1, a key initiator of autophagy, allowing ATXN3 to protect beclin-1 from proteasome-mediated degradation and thereby enabling autophagy. The presence of an expanded polyQ tract in proteins leads to a self-association that competes with polyQ-mediated interaction with beclin-1 and impairs autophagy in vitro (as observed for ATXN3) and in vivo (as observed for huntingtin), at least in conditions of starvation [85]. If this is the case in aging, SCA3 and other diseases awaits investigation. Indeed, a strong dysregulation of autophagy was described in postmortem brains of SCA3 patients, namely the accumulation of autophagy-related gene (Atg) proteins (e.g., ATG-7) and of autophagosomal microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3), in parallel with reduced beclin-1 levels [86, 87]. However, what happens during the course of the disease remains to be elucidated, as contradictory studies in rodent models of the disease either show an abnormal expression of endogenous autophagic markers, accumulation of autophagosomes, and decreased levels of beclin-1 [86] or show no changes in these and in additional autophagy markers [88]. This could be explained by differences in disease severity and progression rates among distinct models. In addition, while some studies showed that genetic and pharmacological activation of autophagy suppressed pathogenesis in a subset of disease models [84, 86, 89,90,91,92,93], others showed very limited impact on animals’ ataxic phenotypes, highlighting that autophagy activating drugs should be used with caution due to possible toxicity issues that may occur during chronic administration [94, 95].

ATXN3 also facilitates the clearance of misfolded proteins by autophagy through its role in aggresome formation. Aggresomes are a cytoplasmic juxtanuclear structure to which misfolded proteins are actively transported in cellular states in which the capacity of the chaperone-refolding system and of the UPS is exceeded. Aggresome formation is therefore recognized as a cytoprotective response serving to sequester potentially toxic misfolded proteins and facilitate their clearance by autophagy. ATXN3 colocalizes with aggresomes and preaggresome particles of the misfolded cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) mutant CFTRΔF508 and interacts with proteins involved in their formation and regulation, such as dynein and histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6). Small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of ATXN3 greatly reduces aggresomes formed by CFTRΔF508, demonstrating a critical role of ATXN3 in this process [96, 97].

Overall, these findings suggest that ATXN3 aggregation may target directly or indirectly a metastable subproteome, thereby causing an increased susceptibility to multifactorial toxicity and, eventually, the collapse of many essential cellular functions, and this may help to explain the phenotypic complexities displayed in SCA3. The impact of the ATXN3 aggregation process in the different housekeeping cellular functions will be described in the following sections.

Impact of ATXN3 Misfolding on DNA Repair, Transcription, and Translation

Quality control studies in the nucleus have traditionally focused on how the cell maintains the integrity of the nuclear genome and the quality of messenger RNA (mRNA) prior to export from the nucleus. Initial studies found that ATXN3 interacts with 2 proteins: HHR23A and HHR23B that are both homologs of the DNA repair protein Rad23 [98] and with ubiquilin (UBQLN)-2 [99]. The fact that mutant ATXN3 sequesters endogenous Ub adaptors into inclusions caused a reduction in the available quantity of HHR23B, which failed to stabilize the xeroderma pigmentosum group C (XPC), a protein involved in nucleotide excision DNA repair mechanisms [99]. Moreover, the interaction of ATXN3 and Rad23 proteins was found to regulate toxicity of pathogenic ATXN3 in vivo [100, 101]. The discovery of the interaction of ATXN3 with the DNA end–processing enzyme polynucleotide kinase 3′-phosphatase (PNKP) renewed the interest on the interplay between protein aggregation and DNA repair. A model has been proposed in which the ATXN3–PNKP interaction coordinately promotes DNA repair. However, mutant ATXN3 can either sequester PNKP in aggregates or inhibit PNKP on its native complex, therefore preventing PNKP-mediated DNA repair activity in a dominant manner [102]. Although no hypersensitivity to DNA-damaging agents has yet been reported in SCA3 patients, a dramatic increase in DNA damage in mutant ATXN3 cells, SCA3 mouse brains, and brain sections from SCA3 patients further supported the impact of ATXN3 aggregation and toxicity in DNA repair [103, 104]. Importantly, this increase in DNA damage was linked to an activation of the ataxia telangiectasia–mutated (ATM) signaling pathway [103], corroborating previous work that showed that mutant ATXN3 expression resulted in p53 activation and apoptotic cell death [105]. Of notice, loss-of-function mutations of PNKP in humans are also a cause of ataxia [106, 107], reinforcing the link between the ATXN3-related networks and cerebellar dysfunction.

On the other hand, the nucleus has a unique proteome due to the abundancy of positively charged proteins that interact with the DNA (such as histones); it is enriched in proteins that present low complexity and intrinsic disorder regions, suggesting conformational flexibility, and there is a permanent remodeling of the chromatin which involves continuous assembly and disassembly of DNA–RNA–protein complexes. This may constitute a considerable source of protein misfolding and aggregation specific to the nucleus. In addition, it is thought that the mechanisms that ensure PQC in the nucleus are distinct from those of other organelles [108, 109], an example being the exclusive use of K48-linked ubiquitin chains required for proteasomal degradation of misfolded proteins, and thus independency of K11-specific ligases and chaperones [110]. Unlike the cytoplasm, the PQC of the nucleus does not handle significant misfolding of nascent proteins. Nuclear PQC is therefore primarily focused on proteins that become misfolded via damage during or after nuclear import, and it is thought that it may have evolved to target specific features of damage-induced misfolding that are particularly harmful in the nuclear environment. In addition to the local effects, failures in cytoplasmic PQC can subsequently burden nuclear PQC pathways by decreasing the levels of correctly folded and functional nuclear proteins. Conversely, dysfunction of nuclear proteins has potential impact in all cellular functions. These factors may explain the increased toxicity when mutant ATXN3 proteins are artificially targeted onto the nucleus in comparison with the cytoplasm, both in vitro and in vivo [111, 112].

In addition, expanded ATXN3 proteins tend to accumulate in the nucleus, where the high protein concentration facilitates its abnormal interactions with transcription factors and cofactors, with histone deacetylases and with regulatory sequences of the DNA [55, 111, 113,114,115,116]. The expansion of the polyQ tract and change in conformation of ATXN3 was reported to alter transcriptional activity in cells by impairing repressor activity, when compared with wild-type ATXN3, of the MMP-2 gene promoter [115], and by reducing capability to activate FOXO-mediated SOD2 expression during oxidative stress [116]. The fact that wild-type ATXN3 binds to components of the transcriptional machinery in cells, as well as the transcriptional changes reported in animal models of SCA3 in the presymptomatic phase, favors the theory of a general transcriptional dysregulation as an initiating factor of SCA3 [117,118,119]. However, more recent reports fail to detect histone hypoacetylation [120], or causative transcriptional changes in the brain of young pre-symptomatic mouse [121], or even report minor gene expression alterations in key brain regions of SCA3 pathology [122]. Consistently, the therapeutic effect reported for the distinct histone deacetylase inhibitors tested, which are expected to activate transcriptional activity in cells, is highly variable among different SCA3 models [118, 120, 123,124,125,126].

Mutant ATXN3 aggregation has been also associated to dysregulation of the microRNA (miRNA) machinery [127,128,129]. Such an alteration in miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression could have a broad impact in cells, including in the negative regulation of ATXN3 expression itself, as the 3′ UTR of human ATXN3 is targeted by miRNAs. The mechanism behind these observations remains to be further elucidated.

Similarly, changes in expression levels of proteins responsible for translation, including Pabpc1, Eif3f, and Eif5a, among other factors, have been associated to SCA3 pathology. However, there is still very little mechanistic insight on these findings [121]. Post-translation modifications of ATXN3 include phosphorylation [130,131,132], ubiquitylation [133,134,135], and SUMOylation [136, 137]. Their impact in the disease initiation and progression needs further investigation in vivo, but in general, these modifications in mutant ATXN3 were shown to modulate its stability, subcellular localization, enzymatic activity, neuroprotective function, self-assembly, its interaction affinity with molecular partners, and/or pathogenicity.

Impact of ATXN3 Misfolding on the Subcellular Compartments: Mitochondria and ER

Wild-type and mutant ATXN3 proteins have also been identified in the mitochondrial protein fraction of cells [138, 139], suggesting that mitochondrial function may be impaired as a result of ATXN3 misfolding and aggregation. In fact, mitochondrial resident proteins were described as ATXN3 interaction partners [139], like the mitochondrial genome maintenance exonuclease 1 (MGME1), which is linked to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) repair. Interestingly, a subset of those mitochondrial proteins, namely the cytochrome C oxidase subunit NDUFA4 (NDUFA4), the complex II succinate dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) iron–sulfur subunit (SDHB), and cytochrome C oxidase assembly factor 7 (COA7), was found to be enriched in the expanded polyQ ATXN3 samples compared to wild-type, suggesting a stronger interaction [139]. Although much of the evidence described above come from cellular fractionation studies that will need validation, these findings may explain the mitochondrial dysfunction reported in in vitro and in vivo SCA3 models, namely mtDNA deletions and reduced copy number that are often found in SCA3 cells, transgenic mice, and patients; the reduced complex II activity in SCA3 patient lymphoblast cell lines and cerebellar granule cells from transgenic mice; the altered mitochondrial morphology and respiration; the increased oxidative stress and mutant ATXN3-mediated cell death; as well as the metabolic disruption detected in the cerebrospinal fluid of SCA3 patients [140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147]. Consistent with this, creatine administration, which increases the concentration of the energy buffer phosphocreatine exerting protective effects in the brain, slowed disease progression and improved motor dysfunction and neuropathology of SCA3 mice [148].

Mutant ATXN3 misfolding also disrupts the homeostasis of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) likely by affecting the degradation of proteins of the secretory pathway [149]. ER-associated degradation (ERAD) is a quality control system responsible for degrading misfolded proteins and unassembled polypeptides of protein complexes [150,151,152]. ERAD is a multistep mechanism that uses VCP/p97, which extracts proteins from the ER and delivers them to proteasomes for degradation in the cytosol [153,154,155]. Mutant ATXN3 binds excessively to VCP [156], decreasing ER retrotranslocation and degradation of ERAD substrates [76]. The accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER may contribute to a further disruption of proteostasis and to SCA3 pathogenesis. Chemical modulation of the unfolded protein response of the ER therefore contributed to a suppression in ATXN3 aggregation and toxicity in nematode models of the disease [157].

Intracellular calcium (Ca2+) levels have also been shown to be modulated by the presence of mutant ATXN3 proteins. Mutant ATXN3 specifically binds and activates the type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R1), potentiating Ca2+ release from ER storages [158]. Moreover, exposure of neuronal cell cultures to exogenous ATXN3 oligomers induced intracellular Ca2+ influx [159]. Ca2+ overload can be detrimental and culminate in cell death through mitochondrial permeabilization, oxidative stress, disruption of cytoskeleton organization, and/or calpain activation [160]. Chronic administration of a Ca2+ stabilizer, dantrolene, reduced neurological symptoms of SCA3 transgenic mice [158], suggesting that mutant ATXN3-mediated dysregulation of Ca2+ signaling plays a role in pathogenesis.

Contributions to Non-cell Autonomous Impact of ATXN3 Misfolding: Axonal Transport and Neurotransmission

Proper neuronal function, survival, and communication require axonal transport as well as intact neurotransmission. The fact that mutant ATXN3 aggregates are also found in axons and that components that ensure protein homeostasis are in close proximity led to the hypothesis that the aggregation process occurring within axons may affect mechanisms of axonal transport of mRNA, proteins, and organelles and thereby contribute to a wider neuronal dysfunction in SCA3 [30]. Age-related axonal neuropathy and metabolic abnormalities in a subset of SCA3 patients further support this hypothesis [161, 162].

The aggregation of mutant ATXN3 proteins in vivo was associated to interrupted synaptic transmission. This was inferred by administrating drugs that target acetylcholine neurotransmission to SCA3 nematodes. Susceptibility to modulators of acetylcholine signaling combined with in vivo imaging suggested an impairment in acetylcholine release from presynaptic neurons, through trapping of vesicles into mutant ATXN3 aggregates [163]. In addition, transcriptomic analysis of brains of 2 independent SCA3 transgenic mouse models reported downregulation of genes involved in glutamatergic and alpha-adrenergic neurotransmission and alterations in CREB pathways, as well as in axon guidance molecules, some of these alterations being already present at presymptomatic ages [117, 122]. Defects in glutamatergic signaling were further explored at the functional level through electrophysiology [94, 119]. Despite all this evidence suggesting that disruption of protein homeostasis may impair interneuronal communication, the specific mechanisms linking ATXN3 to these effects remain to be investigated. Interestingly, 2 unbiased drug repurposing screens of SCA3 cellular and animal models identified compounds that modulated neurotransmission as suppressors of mutant ATXN3 pathogenesis [164, 165]. Citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor that enhances serotonergic neurotransmission by blocking serotonin reuptake at the presynapse, restored motor coordination, aggregation, and neuronal survival in mice, and aripiprazole, an antipsychotic whose efficacy mainly reflects a combined action on dopaminergic and serotonergic signaling, reduced abundance, aggregation, and toxicity of mutant ATXN3 in vivo. However, it is possible that these compounds are indeed correcting protein homeostasis, rather than a pre-existing defect in neurotransmission.

Towards Cellular Targets for Therapy in SCA3: Lessons from Preclinical Models

So far, we have proposed that the primary pathogenic mechanism in SCA3 is indeed the loss of normal quality control of protein folding and interactions, therefore compromising their function. While there is a multitude of affected cellular processes, these are likely a consequence of the initial insult, as the cause of SCA3 is uniquely a mutation in the ATXN3 gene. This observation should move researchers to focus on the targeting of protein homeostasis when aiming to develop new treatments. Nevertheless, improving the overall cellular function can also be beneficial for patients, independent of the targeted alterations being primary or consequential. While SCA3 has an adult onset, alterations in the CNS precede symptom appearance [166, 167]: therefore, correcting the mutation in ATXN3 in the disease state might not be fully beneficial, as neurons could already have irreversible changes. If this is the case, complementary therapies that tackle different modalities of neuron dysfunction can be important, as well as the initiation of treatment as early as possible.

As expected, with the increasing knowledge of SCA3 pathophysiology, researchers have tested multiple drugs that target previously identified abnormal processes. Several of these compounds have been tested in preclinical trials in rodent models of disease (Tables 1 and 2; previously reviewed in detail [174]). Improving the folding/aggregation changes observed with mutant ATXN3 has been successful with compounds such as 17-DMAG (an Hsp90 inhibitor and autophagy inducer), temsirolimus (a rapamycin analog that increases autophagy), cordycepin (autophagy inducer), and H1152 (a ROCK inhibitor shown to decrease levels of mutant ATXN3) [84, 90, 92, 172]. On the other hand, treatment with lithium chloride, an autophagy inducer, had negative results in a preclinical mouse model [88] and in patients [175], which may raise questions on the likelihood of autophagy as a promising target. Importantly, small molecules or biological proteostasis regulators should aim for the enhancement and/or adaptation of protein homeostasis capacity in such a way that they prolong the time period in which cells are able to adequately handle aberrant protein species and not to continuously activate a cellular stress response, as that can be highly toxic.

Regarding nonprimarily affected processes, several compounds also had promising outcomes: dantrolene (targeting calcium-signaling dysregulation), sodium butyrate (modulating transcription through HDAC inhibition), creatine (improving defective energy production), and several modulators of neurotransmission (such as citalopram and riluzole) [118, 148, 158, 170, 171, 176]. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that the positive effect of these compounds does not arise from directly targeting protein homeostasis and/or mutant ATXN3 itself [171].

We will now proceed to briefly review the current clinical management and therapeutic perspectives for SCA3, and more importantly, we will provide a critical view on how specific characteristics of this disease should guide the evolution of translational research and clinical trials (Fig. 2).

Pipeline for therapeutic advances in SCA3. Based on the molecular pathogenesis of SCA3, several drugs that target various aspects of dysfunction have been tested in preclinical models of the disease. Drugs with promising preclinical trial results should be evaluated for their potential translation, namely to be acutely safe, chronically tolerated, have long-term efficacy without loss of effects, and be accompanied by drug-specific biomarkers and measures of drug target engagement. These are the drugs that should reach clinical trials first; if a drug is repurposable, a regulatory fast track can be used to reach the clinical trials more easily. Clinical studies in SCA3 also hold some particularities that are essential for their planning and design. Novel drugs or interventions that reach the clinical setting have to be integrated in the patient hub, which also includes symptom-directed treatments (pharmacological and nonpharmacological) and the patient associations and support groups. ASO = antisense oligonucleotide; ICARS = International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale; polyQ = polyglutamine; SARA = scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia; SCA = spinocerebellar ataxia

Current Status of the Management of SCA3 Patients

As for all SCAs, the current treatment options for SCA3 are purely symptom-directed [174, 177, 178]. Recent guidelines for the diagnosis and management of progressive ataxias have been published and updated [179]: these encompass treatments for individual symptoms based on grading of recommendations, without specification for each disease. It is interesting to note that 52 out of the 62 lines of treatment are based on a Good Practice Point (GPP) grade of recommendation which, despite being very helpful and important for patients, does not rely on a structured body of evidence [180]. A consensus on the management of chronic ataxias in adulthood has also outlined recommendations [181], proposing varenicline, a partial agonist of the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, for the treatment of ataxia in SCA3 (grade B recommendation) [180, 182]. Besides this, as well as the non-SCA3-specific recommendations in the guidelines for the management of progressive ataxias [179], clinicians are left to themselves to work out the best solutions for each patient. The clear lack of clinical trials and therapeutic follow-up studies for SCA3 has not allowed the establishment of a pipeline that standardizes patient management and provides the best evidence-based care. Moreover, the small sample size and short duration of the trials completed to date have also been a strong limitation in the identification of effective therapeutic strategies.

The type of treatment currently offered to each SCA3 patient depends on 1) the clinical subtype of the disease, 2) presenting symptoms, and 3) associated comorbidities [12, 183, 184]. Treatment response is variable, with continuous monitoring of patients’ symptoms being necessary to adjust it accordingly [12, 181]. A symptom-based list on the currently available pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies is detailed in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Surgery is also available as an end-stage option, when other treatments have failed or are no longer sufficient to ensure quality of life for patients. Neurosurgery with deep brain stimulation is an option for unmanageable dystonia or tremor [230, 231], rhizotomy for severe spasticity with associated deformities [232], and percutaneous gastrostomy to ensure adequate nutrition when dysphagia is severe [233]. In conclusion, while targeted therapies do not reach the clinic, a multimodal and dynamic approach is essential to ensure quality of life for patients, with each receiving personalized care according to the most debilitating symptoms.

Clinical Trials in SCA3: Advances and Challenges

Several clinical trials have been carried out for SCA3, but none has yet provided a robust and impactful treatment for patients [234]. Table 2 summarizes information on trials that are ongoing or have been completed recently. Currently, there are 4 active interventional studies for SCAs that include SCA3 patients: 2 with drugs (troriluzole and BHV-4157, a prodrug of riluzole; NCT03701399 and NCT03408080, respectively), 1 with umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell therapy (NCT03378414), and 1 with cerebello-spinal transcranial direct current stimulation (NCT03120013). To date, there have been a total of 15 interventional studies in SCA3 or that included SCA3 patients [234]. While multiple compounds and approaches have been suggested in the preclinical setting as potential treatments for SCA3 [174, 178], little has translated to clinical studies, which is clear by the small number of interventional trials carried out so far.

Despite all efforts, no treatment has proven to be robustly efficient. It is important to attempt to understand the reasons underlying this lack of efficacy, in order to improve future trials. One hypothesis is that most drugs that were tested in patients to date lack proper preclinical evidence supporting their beneficial effect. In fact, the rationale for their use was the promising evidence from trials in other neurological diseases, rather than mechanistic information to support their use in SCA3. Moreover, most of the tested compounds do not target primary ATXN3-related PQC mechanisms, counteracting instead one of the many downstream consequences of this insult [174]. Therefore, it is understandable that most drugs had moderate effects at best. For example, several neurotransmission modulators have been tested (such as tandospirone, riluzole, fluoxetine, varenicline, and valproate), with mild to no efficacy in improving ataxic symptoms [182, 187, 189, 190, 193, 235]; while neuroprotection and synaptic transmission improvement might have been achieved, the other processes that are affected due to the ATXN3 mutation most likely remained unaddressed. A similar reasoning can be used for autophagy modulation with lithium-based compounds, which was of no benefit in mouse models and had limited impact in human trials [88]. Interestingly, preclinical data has suggested that compounds thought to target downstream processes of ATXN3 aggregation have also an effect on the primary loss of PQC mechanisms, namely citalopram, creatine, and trehalose, making them great contenders for translation [148, 164, 236]. In summary, efforts to uncover disease-modifying treatments in SCA3 should have a robust mechanistic background and, more importantly, sufficient preclinical data to support their reliability and efficacy prior to a potential clinical trial.

Clinical trials in rare diseases face several challenges and are usually harder to carry out than for more common disorders [237]. Therefore, studies for this type of disorders are endowed with regulatory flexibility from consumer protection agencies [238]. Rare diseases are defined as having a prevalence of 4 to 5 cases per 10,000 or lower [239]. Autosomal dominant SCAs make part of this group, having a prevalence of 2.7 cases per 100,000 [240], SCA3 being the most prevalent autosomal dominant SCA [240]. This disease is in a relatively privileged position when it comes to clinical trials: it can benefit from special regulations while having studies with sufficient sample size to have more powerful, reliable, and replicable results. Among all the special regulations that exist for rare diseases, the most important for SCA3 are 1) the possibility of orphan drug status [241], 2) the financial breaks on approved drugs and devices [242], and 3) the possibility of combining trial phases [237]. This can motivate researchers to pursue the translational of therapeutics to the patient setting.

Interestingly, while clinical trials are lacking, there are several disadvantages of these studies in rare diseases that can be easily overcome in the case of SCA3. First, the poor understanding of the natural history of rare diseases hinders the establishment of proper endpoints, interventional window, and primary outcomes [237]. For SCA3, 2 longitudinal cohort studies (follow-up visits after 1 year and 2 years for the first; median observation time of 49 months for the second) were able to provide valuable information on its natural history, estimate the sample size needed for statistically powerful clinical trials, and conclude on the patients/disease’s characteristics that correlate more with disease progression [243, 244]. On the other hand, the evaluated population was based on European centers only, which limits the confidence for extrapolation to other cohorts, because SCA3 patients show high clinical heterogeneity [245]. Nevertheless, data on the natural history of disease can also be drawn from patients in clinical trials which are not engaged in treatment [175, 246].

Second, the establishment of clinical meaningful readouts is also a problem for disorders with such low prevalence [234, 237]. In the case of ataxic syndromes, 2 scales are commonly used: the scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia (SARA) [247] and the international cooperative ataxia rating scale (ICARS) [248]. While small changes in the scores of these scales might be statistically significant in trials, the impact of such in patient’s symptoms and quality of life can be meaningless, being important to thoroughly define which score changes are, in fact, impactful [249]. Despite this, several studies have proposed these scores as the best qualitative measure for ataxic symptoms and these have been validated in several populations [250,251,252,253,254]. Since consensus on the best scale to use is hard to achieve with current evidence, clinical researchers should report several different scores, as this allows direct comparison with other studies, which are likely to have used at least one of the same scales. Natural history was also assessed with the SARA score, allowing the standardization of future studies [243, 244]. Finally, noncerebellar symptoms have been also evaluated in the natural history of SCA3 and should be reported thoroughly, as these can also be extremely debilitating for patients [255].

While the gold standard for interventional studies is a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial, this is often impractical for rare diseases, mostly due to the extremely low prevalence and geographical scattering of patients [256]. In fact, 10 out of the total 15 clinical trials performed to date in SCA3 are either open label or lack a placebo arm (Table 2) [174]. This is a common practice in genetic diseases because these are often extremely severe, and it is best conduct to treat all patients in the trial with the experimental intervention [257]. However, the conclusions that can be drawn are weaker and more biased [258]. In SCA3, progression is slow and the disease does not affect development (contrary to several pediatric genetic disorders) [183]: ethically, this supports the feasibility of a robust clinical trial. Furthermore, having already knowledge on natural history and validated tools for outcome assessment, placebo-controlled trials can be designed in a way that conclusions are provided much faster and with less insecurity, enabling all patients to undergo treatment quickly [259].

The final aspect regarding clinical trials in SCA3 is the inclusion of this disease in a group of disorders based on similar clinical presentation (spinocerebellar ataxia) and pathogenesis (triplet repeat expansions) [260]. Researchers have been studying the commonalities between all polyQ SCAs (SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7, and SCA17) to uncover similar mechanisms of pathophysiology that are targetable as treatments [31, 261, 262]. In fact, 5 out of the 15 clinical studies in SCA3 have also included patients with other polyQ SCAs (Table 2) [174]. This strategy has the obvious disadvantage of leaning away from disease-specific changes that could also be interesting therapeutic targets, but can very significantly increase the sample size of clinical trials. In conclusion, clinical trials for SCA3 have been sparse and underwhelming in terms of their power to detect change, yet there are several advances and opportunities that should allow for a sorely needed increase in the number of interventional studies that can be performed.

Translational Potential of Current Experimental Therapies: Key Aspects to Consider

Extensive research in vitro and in animal models has provided important clues on the pathogenesis of SCA3 and proposed strategies for treatment [178]. Moreover, numerous preclinical trials in different mouse models have been carried out, creating a long list of compounds and therapeutic approaches that have proven efficiency preclinically [174] (Fig. 2). Since it is not likely that all treatments will be used in interventional studies, it is important to select those with higher efficiency potential and which adapt to the characteristics of the disease. In the specific case of SCA3, one of the most important aspects of a potential treatment is that it likely needs to be administered in a lifelong manner [179, 181]. For example, drugs with side effects that eventually lead to disability should be avoided in such a chronic setting. Moreover, the treatment should be able to reach the central nervous system, which is a difficulty for both drugs (must cross the blood–brain barrier or be administered intrathecally) [263] and devices (surgical access to the CNS might be required). While in some extremely severe and rapid progressing rare diseases it is feasible to overlook these problems, SCA3 has an adult onset and slow progression, making these issues important barriers to overcome. Despite all, one advantage for SCA3 patients is the possibility of initiating treatment presymptomatically, because genetic testing can be performed [6]. In fact, previous work has highlighted that patients would be more likely to undergo presymptomatic genetic testing if treatment was available [264]. Therefore, drugs and devices that translate to patients should be thoroughly selected based not only on their efficiency but also on how realistic their use can be.

Pharmacological treatment options which had positive results in preclinical trials but have never translated to human studies have their characteristics summarized in Table 1. Clinical trials with drugs that are already actively used in the clinic have several advantages, because drug repurposing can undergo a fast track regarding regulations [265]. These compounds have already been tested for their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, have well-established side effects, and often have available information regarding chronic administration [266]. While no prediction is a guarantee of success, this information can help in the choice of which drugs to test first in patients, as well as which are the least likely to succeed.

Regarding the repurposing of drugs for SCA3 that have positive preclinical data, caffeine likely has a benign course with chronic administration, but can eventually lose effect due to desensitization as previously reported [267]. Citalopram is a good contender because chronic administration has been thoroughly shown to be mostly benign [268], and no long-term loss of effect has been reported in patients. Dantrolene has little side effects, but its muscle-relaxing effect can be overwhelming for patients and might increase bias in clinical studies [269]. Temsirolimus is unlikely to reach the clinic because it has devastating side effects even with acute administration, having its use likely restricted to the oncology field [270]. All other drugs with a positive effect in neurological symptoms in a preclinical trial in SCA3 rodent models (and which have not been tested in SCA3 patients) are not used in the clinic for other disorders.

Drugs which are available as over-the-counter supplements have the advantage of having a good safety profile [271], yet face one of the largest difficulties in translating to patients: the lack of financial support from commercial sponsors [272, 273]. This makes the possibility of a large, well-designed trial very small. In SCA3, creatine is a potentially beneficial supplement with little side effects and extensive information on its characteristics [274]. Resveratrol has also shown very interesting properties in several disorders, including SCA3, but its pharmacokinetic properties have negatively impacted its entrance in the clinical setting [275]. Finally, regarding experimental drugs which have never been tested in patients and are not commercialized, prediction of their success is very hard and is only based on their described mechanism of action in vitro and in animal models. Drugs that target essential cellular processes or pleiotropic pathways must be assessed with caution in patients. Regarding SCA3, compounds such as 17-DMAG (HSP90 inhibitor), sodium butyrate (histone deacetylase inhibitor), and H1152 (ROCK inhibitor) must have their symptom reduction vs side effect profile carefully evaluated, because they target processes that are ubiquitous [276, 277].

Gene therapy is another highlight of potential approaches for SCA3. With the enormous growth of techniques for gene editing, the elimination of the underlying cause of the disease is a highly attractive possibility [278]. The use of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) established one of the major steps towards gene therapy, with nusinersen (an ASO that increases levels of full-length SMN protein) being the first clinically approved therapy for spinal muscular atrophy [279]. In SCA3, ASOs have been used either to decrease overall ATXN3 levels or to generate a truncated ATXN3 which lacks the polyQ expansion [280, 281]. While these are promising strategies, it is essential that the suggested effects of loss-of-function ATXN3 [71] are well studied in order to evaluate if the beneficial effects outweigh the risks, particularly because ATXN3 gene silencing in some cell types has been shown to cause accumulation of DNA damage, increased proliferation, and loss of adhesion and of differentiation, all of which are hallmarks of cancer [71, 282]. Furthermore, the need for intrathecal administration of ASOs is also a downside of this approach. Another gene-directed strategy that has been tested with positive results is the use of short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting mutant ATXN3 [283]. Moreover, the safety profile of lentiviral-mediated delivery of shRNAs has also been established, making a step towards translation [284]. However, the challenges for viral-mediated approaches are some of the largest in the clinical trial setting: the inflammatory response to viral particles, the tissue-unspecific uptake of the content, the lack of entry in target cells, oncogenic side effects, and the overall absence of effect in most clinical trials carried out are some of the aspects that make these types of approaches hard to implement [285,286,287,288]. Finally, while CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been employed to remove the polyQ tract of ATXN3 in iPSCs [289], no preclinical trials in rodents have been published. In summary, while there is a significant number of contender approaches for clinical trials, we should privilege those with a higher chance of not only being efficient, but also having a realistic potential of being established as a treatment for SCA3.

Managing Patients’ Expectations Regarding Therapy Development

Patients that suffer from rare diseases, for which little treatment options are available, tend to be more aware of progress in research [290, 291]. Since the concept of a genetic disorder is usually harder to grasp for patients, it is important that clinicians take time to properly explain essential concepts [291]. This not only empowers patients but also avoids false judgment regarding new therapeutic developments, because research databases are also available to the general public [292]. Hence, it is extremely important that SCA3 patients are appropriately informed not only at the time of diagnosis but also in follow-up visits when it comes to progresses in research.

One of the most important interfaces that bridge patients and research is the supporting organizations [293]. Several organizations for patients with ataxic syndromes exist throughout the world, and patients should be encouraged to become part of them [294]. A central aspect of these organizations is that they are a platform for the transmission of information to patients, creating a privileged setting to “translate” newly published research into lay language, therefore informing while ensuring scientific reliability [295]. Furthermore, organizations are also an important mean of recruiting patients to clinical trials, because a direct contact is easily made [296].

Finally, it is crucial that clinicians manage patient’s expectations towards the development of treatments [297]. Professionals should consistently and reliably inform patients but also explain the difficulty and challenges of therapy development in the context of rare disorders. These approaches should provide the patient with a realistic expectation on its condition while maintaining hope for the possibility of a new treatment being developed and translated into practice.

Conclusion

In this review, we have provided an extensive overview of the main questions that remain unanswered regarding the molecular pathogenesis of SCA3, and what does the extensive and high-quality research so far teach us on the more likely initial events that compromise cellular function. We also addressed the translational/clinical research development and provided a realistic perspective of what can be expected from future interventional studies. While research for rare diseases faces harder challenges than more common disorders, SCA3 has a privileged setting regarding clinical trials, and its epidemiological, clinical, and molecular specificities should be the main drivers of research. Therefore, scientists should work for realistic goals in the hope of optimizing the research process, ensuring that it will help improve the quality of patients’ lives in the end.

References

Lima L, Coutinho P. Clinical criteria for diagnosis of Machado-Joseph disease: report of a non-Azorena Portuguese family. Neurology. United States; 1980;30:319–22.

Takiyama Y, Nishizawa M, Tanaka H, Kawashima S, Sakamoto H, Karube Y, et al. The gene for Machado-Joseph disease maps to human chromosome 14q. Nat Genet. United States; 1993;4:300–4.

Kawaguchi Y, Okamoto T, Taniwaki M, Aizawa M, Inoue M, Katayama S, et al. CAG expansions in a novel gene for Machado-Joseph disease at chromosome 14q32.1. Nat Genet. United States; 1994;8:221–8.

Maciel P, Gaspar C, DeStefano AL, Silveira I, Coutinho P, Radvany J, et al. Correlation between CAG repeat length and clinical features in Machado-Joseph disease. Am J Hum Genet. United States; 1995;57:54–61.

Wang G, Ide K, Nukina N, Goto J, Ichikawa Y, Uchida K, et al. Machado-Joseph disease gene product identified in lymphocytes and brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. United States; 1997;233:476–9.

Bettencourt C, Lima M. Machado-Joseph Disease: from first descriptions to new perspectives. Orphanet J Rare Dis. England; 2011;6:35.

Moro A, Munhoz RP, Arruda WO, Raskin S, Moscovich M, Teive HAG. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3: subphenotypes in a cohort of Brazilian patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. Brazil; 2014;72:659–62.

Sudarsky L, Coutinho P. Machado-Joseph disease. Clin Neurosci. United States; 1995;3:17–22.

Gwinn-Hardy K, Singleton A, O’Suilleabhain P, Boss M, Nicholl D, Adam A, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 phenotypically resembling Parkinson disease in a black family. Arch Neurol. United States; 2001;58:296–9.

Taroni F, DiDonato S. Pathways to motor incoordination: the inherited ataxias. Nat Rev Neurosci. England; 2004;5:641–55.

Rub U, Brunt ER, Deller T. New insights into the pathoanatomy of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (Machado-Joseph disease). Curr Opin Neurol. England; 2008;21:111–6.

D’Abreu A, Franca MCJ, Paulson HL, Lopes-Cendes I. Caring for Machado-Joseph disease: current understanding and how to help patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. England; 2010;16:2–7.

Klinke I, Minnerop M, Schmitz-Hubsch T, Hendriks M, Klockgether T, Wullner U, et al. Neuropsychological features of patients with spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) types 1, 2, 3, and 6. Cerebellum. United States; 2010;9:433–42.

Scherzed W, Brunt ER, Heinsen H, de Vos RA, Seidel K, Burk K, et al. Pathoanatomy of cerebellar degeneration in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) and type 3 (SCA3). Cerebellum. United States; 2012;11:749–60.

Durr A, Stevanin G, Cancel G, Duyckaerts C, Abbas N, Didierjean O, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia 3 and Machado-Joseph disease: clinical, molecular, and neuropathological features. Ann Neurol. United States; 1996;39:490–9.

Paulson HL, Das SS, Crino PB, Perez MK, Patel SC, Gotsdiner D, et al. Machado-Joseph disease gene product is a cytoplasmic protein widely expressed in brain. Ann Neurol. United States; 1997;41:453–62.

Yamada M, Hayashi S, Tsuji S, Takahashi H. Involvement of the cerebral cortex and autonomic ganglia in Machado-Joseph disease. Acta Neuropathol. Germany; 2001;101:140–4.

Munoz E, Rey MJ, Mila M, Cardozo A, Ribalta T, Tolosa E, et al. Intranuclear inclusions, neuronal loss and CAG mosaicism in two patients with Machado-Joseph disease. J Neurol Sci. Netherlands; 2002;200:19–25.

Yamada M, Sato T, Tsuji S, Takahashi H. CAG repeat disorder models and human neuropathology: similarities and differences. Acta Neuropathol. Germany; 2008;115:71–86.

Alves S, Regulier E, Nascimento-Ferreira I, Hassig R, Dufour N, Koeppen A, et al. Striatal and nigral pathology in a lentiviral rat model of Machado-Joseph disease. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2008;17:2071–83.

Murata Y, Yamaguchi S, Kawakami H, Imon Y, Maruyama H, Sakai T, et al. Characteristic magnetic resonance imaging findings in Machado-Joseph disease. Arch Neurol. United States; 1998;55:33–7.

Tokumaru AM, Kamakura K, Maki T, Murayama S, Sakata I, Kaji T, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of Machado-Joseph disease: histopathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. United States; 2003;27:241–8.

Paulson HL, Perez MK, Trottier Y, Trojanowski JQ, Subramony SH, Das SS, et al. Intranuclear inclusions of expanded polyglutamine protein in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Neuron. United States; 1997;19:333–44.

Schmidt T, Landwehrmeyer GB, Schmitt I, Trottier Y, Auburger G, Laccone F, et al. An isoform of ataxin-3 accumulates in the nucleus of neuronal cells in affected brain regions of SCA3 patients. Brain Pathol. Switzerland; 1998;8:669–79.

Rub U, Brunt ER, Petrasch-Parwez E, Schols L, Theegarten D, Auburger G, et al. Degeneration of ingestion-related brainstem nuclei in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2, 3, 6 and 7. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. England; 2006;32:635–49.

Rub U, de Vos RAI, Brunt ER, Sebesteny T, Schols L, Auburger G, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3): thalamic neurodegeneration occurs independently from thalamic ataxin-3 immunopositive neuronal intranuclear inclusions. Brain Pathol. Switzerland; 2006;16:218–27.

Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature. England; 2004;431:805–10.

Takahashi T, Katada S, Onodera O. Polyglutamine diseases: where does toxicity come from? what is toxicity? where are we going? J Mol Cell Biol. United States; 2010;2:180–91.

Hayashi M, Kobayashi K, Furuta H. Immunohistochemical study of neuronal intranuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions in Machado-Joseph disease. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. Australia; 2003;57:205–13.

Seidel K, den Dunnen WFA, Schultz C, Paulson H, Frank S, de Vos RA, et al. Axonal inclusions in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Acta Neuropathol. Germany; 2010;120:449–60.

Seidel K, Siswanto S, Brunt ERP, den Dunnen W, Korf H-W, Rüb U. Brain pathology of spinocerebellar ataxias. Acta Neuropathol. Springer; 2012;124:1–21.

Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. United States; 2008;319:916–9.

Klaips CL, Jayaraj GG, Hartl FU. Pathways of cellular proteostasis in aging and disease. J Cell Biol. United States; 2018;217:51–63.

Hipp MS, Park S-H, Hartl FU. Proteostasis impairment in protein-misfolding and -aggregation diseases. Trends Cell Biol. England; 2014;24:506–14.

Hipp MS, Kasturi P, Hartl FU. The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. England; 2019;20:421–35.

Jahn TR, Radford SE. The Yin and Yang of protein folding. FEBS J. England; 2005;272:5962–70.

Carvalho AL, Silva A, Macedo-Ribeiro S. Polyglutamine-Independent Features in Ataxin-3 Aggregation and Pathogenesis of Machado-Joseph Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. United States; 2018;1049:275–88.

Ellisdon AM, Thomas B, Bottomley SP. The two-stage pathway of ataxin-3 fibrillogenesis involves a polyglutamine-independent step. J Biol Chem. United States; 2006;281:16888–96.

Gales L, Cortes L, Almeida C, Melo C V, Costa M do C, Maciel P, et al. Towards a structural understanding of the fibrillization pathway in Machado-Joseph’s disease: trapping early oligomers of non-expanded ataxin-3. J Mol Biol. England; 2005;353:642–54.

Bevivino AE, Loll PJ. An expanded glutamine repeat destabilizes native ataxin-3 structure and mediates formation of parallel beta -fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. United States; 2001;98:11955–60.

Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, et al. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. United States; 2003;300:486–9.

Berke SJS, Schmied FAF, Brunt ER, Ellerby LM, Paulson HL. Caspase-mediated proteolysis of the polyglutamine disease protein ataxin-3. J Neurochem. England; 2004;89:908–18.

Haacke A, Broadley SA, Boteva R, Tzvetkov N, Hartl FU, Breuer P. Proteolytic cleavage of polyglutamine-expanded ataxin-3 is critical for aggregation and sequestration of non-expanded ataxin-3. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2006;15:555–68.

Breuer P, Haacke A, Evert BO, Wullner U. Nuclear aggregation of polyglutamine-expanded ataxin-3: fragments escape the cytoplasmic quality control. J Biol Chem. United States; 2010;285:6532–7.

Wellington CL, Ellerby LM, Hackam AS, Margolis RL, Trifiro MA, Singaraja R, et al. Caspase cleavage of gene products associated with triplet expansion disorders generates truncated fragments containing the polyglutamine tract. J Biol Chem. United States; 1998;273:9158–67.

Jung J, Xu K, Lessing D, Bonini NM. Preventing Ataxin-3 protein cleavage mitigates degeneration in a Drosophila model of SCA3. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2009;18:4843–52.

Liman J, Deeg S, Voigt A, Vossfeldt H, Dohm CP, Karch A, et al. CDK5 protects from caspase-induced Ataxin-3 cleavage and neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. England; 2014;129:1013–23.

Haacke A, Hartl FU, Breuer P. Calpain inhibition is sufficient to suppress aggregation of polyglutamine-expanded ataxin-3. J Biol Chem. United States; 2007;282:18851–6.

Koch P, Breuer P, Peitz M, Jungverdorben J, Kesavan J, Poppe D, et al. Excitation-induced ataxin-3 aggregation in neurons from patients with Machado-Joseph disease. Nature. England; 2011;480:543–6.

Hubener J, Weber JJ, Richter C, Honold L, Weiss A, Murad F, et al. Calpain-mediated ataxin-3 cleavage in the molecular pathogenesis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3). Hum Mol Genet. England; 2013;22:508–18.

Nobrega C, Simoes AT, Duarte-Neves J, Duarte S, Vasconcelos-Ferreira A, Cunha-Santos J, et al. Molecular Mechanisms and Cellular Pathways Implicated in Machado-Joseph Disease Pathogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. United States; 2018;1049:349–67.

Simoes AT, Goncalves N, Koeppen A, Deglon N, Kugler S, Duarte CB, et al. Calpastatin-mediated inhibition of calpains in the mouse brain prevents mutant ataxin 3 proteolysis, nuclear localization and aggregation, relieving Machado-Joseph disease. Brain. England; 2012;135:2428–39.

Chai Y, Koppenhafer SL, Shoesmith SJ, Perez MK, Paulson HL. Evidence for proteasome involvement in polyglutamine disease: localization to nuclear inclusions in SCA3/MJD and suppression of polyglutamine aggregation in vitro. Hum Mol Genet. England; 1999;8:673–82.

Chai Y, Koppenhafer SL, Bonini NM, Paulson HL. Analysis of the role of heat shock protein (Hsp) molecular chaperones in polyglutamine disease. J Neurosci. United States; 1999;19:10338–47.

Chai Y, Wu L, Griffin JD, Paulson HL. The role of protein composition in specifying nuclear inclusion formation in polyglutamine disease. J Biol Chem. United States; 2001;276:44889–97.

Schmidt T, Lindenberg KS, Krebs A, Schols L, Laccone F, Herms J, et al. Protein surveillance machinery in brains with spinocerebellar ataxia type 3: redistribution and differential recruitment of 26S proteasome subunits and chaperones to neuronal intranuclear inclusions. Ann Neurol. United States; 2002;51:302–10.

Donaldson KM, Li W, Ching KA, Batalov S, Tsai C-C, Joazeiro CAP. Ubiquitin-mediated sequestration of normal cellular proteins into polyglutamine aggregates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. United States; 2003;100:8892–7.

Yang H, Li J-J, Liu S, Zhao J, Jiang Y-J, Song A-X, et al. Aggregation of polyglutamine-expanded ataxin-3 sequesters its specific interacting partners into inclusions: implication in a loss-of-function pathology. Sci Rep. England; 2014;4:6410.

Kim S, Nollen EAA, Kitagawa K, Bindokas VP, Morimoto RI. Polyglutamine protein aggregates are dynamic. Nat Cell Biol. England; 2002;4:826–31.

Olzscha H, Schermann SM, Woerner AC, Pinkert S, Hecht MH, Tartaglia GG, et al. Amyloid-like aggregates sequester numerous metastable proteins with essential cellular functions. Cell. United States; 2011;144:67–78.

Freeman BC, Yamamoto KR. Disassembly of transcriptional regulatory complexes by molecular chaperones. Science. United States; 2002;296:2232–5.

Sousa R, Lafer EM. The role of molecular chaperones in clathrin mediated vesicular trafficking. Front Mol Biosci. Switzerland; 2015;2:26.

Streicher JM. The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Regulating Receptor Signal Transduction. Mol Pharmacol. United States; 2019;95:468–74.

Yu A, Shibata Y, Shah B, Calamini B, Lo DC, Morimoto RI. Protein aggregation can inhibit clathrin-mediated endocytosis by chaperone competition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. United States; 2014;111:E1481–90.

Park S-H, Kukushkin Y, Gupta R, Chen T, Konagai A, Hipp MS, et al. PolyQ proteins interfere with nuclear degradation of cytosolic proteins by sequestering the Sis1p chaperone. Cell. United States; 2013;154:134–45.

Gidalevitz T, Ben-Zvi A, Ho KH, Brignull HR, Morimoto RI. Progressive disruption of cellular protein folding in models of polyglutamine diseases. Science. United States; 2006;311:1471–4.

Doss-Pepe EW, Stenroos ES, Johnson WG, Madura K. Ataxin-3 interactions with rad23 and valosin-containing protein and its associations with ubiquitin chains and the proteasome are consistent with a role in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Mol Cell Biol. United States; 2003;23:6469–83.

Burnett B, Li F, Pittman RN. The polyglutamine neurodegenerative protein ataxin-3 binds polyubiquitylated proteins and has ubiquitin protease activity. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2003;12:3195–205.

Wang H, Ying Z, Wang G. Ataxin-3 regulates aggresome formation of copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) by editing K63-linked polyubiquitin chains. J Biol Chem. United States; 2012;287:28576–85.

do Carmo Costa M, Bajanca F, Rodrigues A-J, Tome RJ, Corthals G, Macedo-Ribeiro S, et al. Ataxin-3 plays a role in mouse myogenic differentiation through regulation of integrin subunit levels. PLoS One. United States; 2010;5:e11728.

Neves-Carvalho A, Logarinho E, Freitas A, Duarte-Silva S, Costa M do C, Silva-Fernandes A, et al. Dominant negative effect of polyglutamine expansion perturbs normal function of ataxin-3 in neuronal cells. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2015;24:100–17.

Liu H, Li X, Ning G, Zhu S, Ma X, Liu X, et al. The Machado-Joseph Disease Deubiquitinase Ataxin-3 Regulates the Stability and Apoptotic Function of p53. PLoS Biol. United States; 2016;14:e2000733.

Chai Y, Berke SS, Cohen RE, Paulson HL. Poly-ubiquitin Binding by the Polyglutamine Disease Protein Ataxin-3 Links Its Normal Function to Protein Surveillance Pathways. J Biol Chem [Internet]. 2004;279:3605–11. Available from: http://www.jbc.org/content/279/5/3605.abstract

Winborn BJ, Travis SM, Todi S V, Scaglione KM, Xu P, Williams AJ, et al. The deubiquitinating enzyme ataxin-3, a polyglutamine disease protein, edits Lys63 linkages in mixed linkage ubiquitin chains. J Biol Chem. United States; 2008;283:26436–43.

Teixeira-Castro A, Ailion M, Jalles A, Brignull HR, Vilaca JL, Dias N, et al. Neuron-specific proteotoxicity of mutant ataxin-3 in C. elegans: rescue by the DAF-16 and HSF-1 pathways. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2011;20:2996–3009.

Zhong X, Pittman RN. Ataxin-3 binds VCP/p97 and regulates retrotranslocation of ERAD substrates. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2006;15:2409–20.

Durcan TM, Kontogiannea M, Thorarinsdottir T, Fallon L, Williams AJ, Djarmati A, et al. The Machado-Joseph disease-associated mutant form of ataxin-3 regulates parkin ubiquitination and stability. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2011;20:141–54.

Bence NF, Sampat RM, Kopito RR. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by protein aggregation. Science. United States; 2001;292:1552–5.

Matsumoto M, Yada M, Hatakeyama S, Ishimoto H, Tanimura T, Tsuji S, et al. Molecular clearance of ataxin-3 is regulated by a mammalian E4. EMBO J. England; 2004;23:659–69.

Tsai YC, Fishman PS, Thakor N V, Oyler GA. Parkin facilitates the elimination of expanded polyglutamine proteins and leads to preservation of proteasome function. J Biol Chem. United States; 2003;278:22044–55.

Jana NR, Dikshit P, Goswami A, Kotliarova S, Murata S, Tanaka K, et al. Co-chaperone CHIP associates with expanded polyglutamine protein and promotes their degradation by proteasomes. J Biol Chem. United States; 2005;280:11635–40.

Blount JR, Tsou W-L, Ristic G, Burr AA, Ouyang M, Galante H, et al. Ubiquitin-binding site 2 of ataxin-3 prevents its proteasomal degradation by interacting with Rad23. Nat Commun. England; 2014;5:4638.

Berger Z, Ravikumar B, Menzies FM, Oroz LG, Underwood BR, Pangalos MN, et al. Rapamycin alleviates toxicity of different aggregate-prone proteins. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2006;15:433–42.

Menzies FM, Huebener J, Renna M, Bonin M, Riess O, Rubinsztein DC. Autophagy induction reduces mutant ataxin-3 levels and toxicity in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Brain. England; 2010;133:93–104.

Ashkenazi A, Bento CF, Ricketts T, Vicinanza M, Siddiqi F, Pavel M, et al. Polyglutamine tracts regulate beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Nature. England; 2017;545:108–11.

Nascimento-Ferreira I, Santos-Ferreira T, Sousa-Ferreira L, Auregan G, Onofre I, Alves S, et al. Overexpression of the autophagic beclin-1 protein clears mutant ataxin-3 and alleviates Machado–Joseph disease. Brain [Internet]. 2011;134:1400–15. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr047

Sittler A, Muriel M-P, Marinello M, Brice A, den Dunnen W, Alves S. Deregulation of autophagy in postmortem brains of Machado-Joseph disease patients. Neuropathology. Australia; 2018;38:113–24.

Duarte-Silva S, Neves-Carvalho A, Soares-Cunha C, Teixeira-Castro A, Oliveira P, Silva-Fernandes A, et al. Lithium chloride therapy fails to improve motor function in a transgenic mouse model of Machado-Joseph disease. Cerebellum. United States; 2014;13:713–27.

Nascimento-Ferreira I, Nobrega C, Vasconcelos-Ferreira A, Onofre I, Albuquerque D, Aveleira C, et al. Beclin 1 mitigates motor and neuropathological deficits in genetic mouse models of Machado-Joseph disease. Brain. England; 2013;136:2173–88.

Silva-Fernandes A, Duarte-Silva S, Neves-Carvalho A, Amorim M, Soares-Cunha C, Oliveira P, et al. Chronic treatment with 17-DMAG improves balance and coordination in a new mouse model of Machado-Joseph disease. Neurotherapeutics. United States; 2014;11:433–49.

Cunha-Santos J, Duarte-Neves J, Carmona V, Guarente L, Pereira de Almeida L, Cavadas C. Caloric restriction blocks neuropathology and motor deficits in Machado-Joseph disease mouse models through SIRT1 pathway. Nat Commun. England; 2016;7:11445.

Marcelo A, Brito F, Carmo-Silva S, Matos CA, Alves-Cruzeiro J, Vasconcelos-Ferreira A, et al. Cordycepin activates autophagy through AMPK phosphorylation to reduce abnormalities in Machado-Joseph disease models. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2019;28:51–63.

Nobrega C, Mendonca L, Marcelo A, Lamaziere A, Tome S, Despres G, et al. Restoring brain cholesterol turnover improves autophagy and has therapeutic potential in mouse models of spinocerebellar ataxia. Acta Neuropathol. Germany; 2019

Konno A, Shuvaev AN, Miyake N, Miyake K, Iizuka A, Matsuura S, et al. Mutant ataxin-3 with an abnormally expanded polyglutamine chain disrupts dendritic development and metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling in mouse cerebellar Purkinje cells. Cerebellum. United States; 2014;13:29–41.

Duarte-Silva S, Silva-Fernandes A, Neves-Carvalho A, Soares-Cunha C, Teixeira-Castro A, Maciel P. Combined therapy with m-TOR-dependent and -independent autophagy inducers causes neurotoxicity in a mouse model of Machado-Joseph disease. Neuroscience. United States; 2016;313:162–73.

Burnett BG, Pittman RN. The polyglutamine neurodegenerative protein ataxin 3 regulates aggresome formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. United States; 2005;102:4330–5.

Olzmann JA, Li L, Chin LS. Aggresome formation and neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic implications. Curr Med Chem. United Arab Emirates; 2008;15:47–60.

Wang G, Sawai N, Kotliarova S, Kanazawa I, Nukina N. Ataxin-3, the MJD1 gene product, interacts with the two human homologs of yeast DNA repair protein RAD23, HHR23A and HHR23B. Hum Mol Genet. England; 2000;9:1795–803.