Abstract

In this article we quantify the aggregate, distributional and welfare consequences of investment expensing and progressivity in Hall and Rabushka type of flat-tax reforms of the US economy. To do so we use a heterogeneous households model featuring both life cycle and dynastic elements as well as nonlinear wage dynamics. Our findings suggest that moving toward a progressive consumption-based flat-tax scheme could achieve the goals of raising government income, stimulating the economy, and providing a safety net for the households that have been hit the hardest by the recession. In particular, we find that investment expensing brings about sizeable output gains and a nontrivial increase in after-tax income inequality. However, it results in aggregate welfare gains in steady state because the large deduction in the labor income tax acts as a boon for the income poor, because the larger capital stock implies that workers earn higher wages, and because investment expensing allows households to abandon poverty faster. We also find that the progressivity of the reforms matters for welfare: economies with more progressive flat-tax schemes are better for the very poor and are ultimately preferred by a Benthamite social planner as they allow households to achieve better consumption smoothing and a better allocation of their work effort across time and states.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Many economists today share the perception that the tax codes in modern market economies are becoming very complex, that they are costly to run, that they are full of loop-holes, and that they create many distortions. The debate on fundamental tax reforms is heating up as some countries, mostly in Eastern Europe, have adopted much simplified tax systems, and as other countries need to increase their tax collections to finance their growing public deficits.

One important aspect being debated is whether fundamental tax reforms should tax a broad definition of income, or whether they should tax exclusively consumption expenditures.Footnote 1 The key distinction between these two families of tax reforms is the tax treatment of investment expenditures. Income-based taxes tax both consumption and investment. This yields a broader tax base, but it generates distortions in capital accumulation. Consumption-based taxes do not tax investment expenditures and they have a smaller tax base. But they do not distort the capital accumulation decision. The classical optimality results of Chamley (1986) and Judd (1985) prescribe only consumption-based taxes because in the long run the distortions in capital accumulation are more severe than the distortions in the labor choices. Against this argument in favor of taxing consumption expenditures exclusively, there are other arguments that defend taxing a broad definition of income. For instance, Aiyagari (1995) points out that when labor income is uncertain and uninsurable the aggregate stock of capital may be too large, and some capital income taxation may be needed in order to bring it back to the modified golden rule of the textbook representative household growth model.

In addition, implementing a consumption tax as a sales tax or as the European value added tax rises concerns about fairness because it is believed that it cannot be made a function of income. However this is not entirely true, since there are ways to design fundamental tax reforms that are both consumption-based and progressive. A famous example is the flat-tax reform originally suggested by Hall and Rabushka (1995). These authors propose to abolish the personal income tax and the corporate income tax and to substitute them with a unified flat tax on labor and business income. This tax scheme is equivalent to a consumption tax because it makes investment expenditures deductible from the business income tax base. The average tax rates on labor income are progressive because a fixed amount of labor income is tax exempt. Simulation results such as those reported by Ventura (1999) or by Altig et al. (2001) find that a reform along these lines generates large increases in the accumulation of productive capital, and nontrivial increases in income and wealth inequality. However, other authors such as Gentry and Hubbard (1997) argue that this type of tax reforms may not generate more inequality than similar reforms that tax all income.

In this article we contribute to the debate on whether fundamental tax reforms should be income-based or consumption-based, and we find that revenue-neutral consumption-based tax reforms should be preferred because they result in larger welfare gains. We also study the role played by the size of the labor income tax deductions in consumption-based reforms, and we find that the welfare gains are increasing in the progressivity of the reforms.

To do so we calibrate a heterogeneous household, general equilibrium model economy to US data and we use it to compare the steady-state aggregate, distributional, and welfare consequences of four fundamental tax reforms. Our model economy is an extension of the model economy described in Castañeda et al. (2003). We introduce the heterogeneity in labor market opportunities using an uninsurable process on the endowment of efficiency labor units that features nonlinear dynamics. Given the labor market opportunity, households choose their work effort.Footnote 2 We model life cycle using stochastic aging and retirement as in Gertler (1999). We model the dynastic links making households altruistic toward their descendants. Once our model economy is properly calibrated, these features guarantee that households in our model economy save for precautionary reasons, for life cycle reasons, and for altruistic reasons. A distinguishing feature of our model economy is that it replicates the US marginal distributions of labor earnings, income, and wealth in very much detail. And, in contrast with the model economies that focus exclusively on life cycle features, it does a particularly good job in replicating the very top tails of those distributions.Footnote 3

We start by evaluating a version of the consumption-based flat-tax reform originally proposed by Hall and Rabushka (1995). To do so, we substitute the current personal and corporate income taxes with an integrated 19% flat tax on labor income and capital income—which we use as a proxy for business income. We deduct investment expenditures from the capital income tax base and we choose the personal deduction on the labor income tax to make the reform revenue neutral. We find that aggregate output and labor productivity increase by 11.3 and 12.6%, and that both after-tax income and wealth inequality increase substantially. Specifically, the Gini index of after-tax income increases from 0.51 to 0.55, and the Gini index of wealth increases from 0.82 to 0.84. These results are consistent with most findings in the literature. But, perhaps surprisingly, we also find that the reform yields welfare gains equivalent to an average increase of 5.2% of consumption in all periods and in all states. These gains come from three sources. First, the large deduction in the labor income tax acts as a boon for the income poor. Second, in the reformed economy the capital stock is larger, which implies that workers earn higher wages. And third, investment expensing allows households to accumulate wealth more effectively and hence it allows them to abandon poverty faster.

To measure the quantitative importance of not taxing the capital accumulation decision at the margin, we compare the allocations that obtain in the reformed economy with those that obtain when we simulate an alternative income-based flat-tax reform where the tax rate remains at 19%, but where investment is not expendable, and where we adjust the deduction in the labor income tax to make the reform revenue neutral. We find that the aggregate gains brought about by this reform are more modest—output increases by only 4%—and that the increases in income and wealth inequality are also smaller—the steady-state Gini index of after-tax income that obtains after the reform is 0.53. Furthermore, we find that this reform reduces aggregate welfare. The reason is that, compared to the economy with investment expensing, the tax deduction in the labor income tax that can be afforded is much lower and hence the very poor are worse off.

To sum up, our contribution to the consumption versus income-based tax reforms is that consumption-based tax reforms bring about larger output gains, more income and wealth inequality and higher aggregate welfare. Admittedly, they shift the tax burden away from the income rich, but the large output gains that consumption-based tax reforms bring about can be used to provide a larger deduction in the labor income tax. And these deductions result in sizable benefits for the very poor.

Our second contribution to the fundamental tax reform debate is to measure the quantitative importance of the labor income tax exemptions in consumption-based flat-tax reforms. To this purpose, we compare the steady-state allocations that obtain in the 19% flat-tax reform with the steady-state allocations of two other reformed economies which differ in the sizes of their flat-tax rates and of their labor income tax exemptions. Specifically, we study a proportional flat-tax reform in which all labor income is taxed at an integrated flat-tax rate of 15.3%, and a very progressive flat-tax reform in which we double the labor income tax deduction and in which the integrated flat-tax rate is 24.7%. In the model economy with the more progressive flat tax, output, consumption, aggregate hours, and the capital stock are all smaller. These results were to be expected. But more surprisingly, we also find that labor productivity is increasing in the progressivity of the reform and that the inequality of income after-taxes is very similar across the three consumption-based tax reforms.

These novel results are justified by a better allocation of household labor hours. It turns out that in the more progressive reforms, household hours are more correlated with labor market productivity. This is because the more progressive tax code provides more insurance against labor market uncertainty, and this allows households to improve their intertemporal allocation of labor, and to make better use of their labor market opportunities—essentially the more progressive tax reforms allow the households to work less when the times are bad. Consequently, since more progressive tax reforms increase the correlation of labor hours with the idiosyncratic labor shocks, they make the distribution of labor earnings before taxes more unequal and the average productivity per hour worked higher. This increased inequality in the distribution of before-tax earnings partly offsets the increased redistribution brought about by the higher labor income tax exemption and the higher flat-tax rate. And they result in similar concentrations of after-tax income.

Finally, we find that the more progressive tax reform brings about the largest welfare gains in spite of the smallest increase in aggregate consumption and the mild decrease in after-tax income inequality. Once again, the reason is that the more progressive flat-tax reform allows households to take better advantage of their labor market opportunities without compromising their ability to smooth consumption. We conclude that progressive consumption-based flat taxes allow households to improve their lifetime allocations of consumption and leisure and that a Benthamite social planner would recommend them because they bring about large welfare gains.

The remaining of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we describe the model economy and in Sect. 3 we discuss how we parameterize it to reproduce the main aggregate and distributional statistics of the US economy. Then, in Sect. 4 we present the results of the economies with the different tax reforms and compare them to the benchmark economy. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes.

2 The model economy

2.1 Population and endowment dynamics

Our model economy is inhabited by a measure one continuum of heterogeneous dynastic households. The households are endowed with \(\ell \) units of disposable time each period, and they are either workers or retirees. Workers face an uninsured idiosyncratic stochastic process that determines their endowment of efficiency labor units. They also face an exogenous probability of retiring. Retirees are endowed with zero efficiency labor units and they face an exogenous probability of dying. When a retiree dies, it is replaced by a working-age descendant who inherits the retiree’s estate and, possibly, some of its earning abilities. We use the one-dimensional shock, s, to denote the household’s random age and random endowment of efficiency labor units jointly.

We assume that the process on s is independent and identically distributed across households, and that it follows a finite state Markov chain with conditional transition probabilities given by \(\Gamma =\Gamma (s' \mid s) = Pr\{s_{t+1} = s' \mid s_{t} = s\}\), where s and \(s'\in S\). We assume that s takes values in one of two possible J-dimensional sets, \(\mathcal{E}\) and \(\mathcal{R}\). Therefore the formal description of set S is \(S = \mathcal{E} \cup \mathcal{R} = \{1,2, \ldots , J\} \cup \{J+1,J+2,\ldots ,2J\}\). When a household draws shock \(s \in \mathcal{E}\), it is a worker and its endowment of efficiency labor units is \(e(s) > 0\). When a household draws shock \(s \in \mathcal{R}\) it is a retiree, and its endowment of efficiency labor units is \(e(s) = 0\). When a household’s shock changes from \(s\in \mathcal E\) to \(s'\in \mathcal R\), we say that it has retired and when it changes from \(s\in \mathcal R\) to \(s' \in \mathcal E\), we say that it has died and has been replaced by a working-age descendant. When a household dies, its estate is liquidated, and its descendant inherits a fraction \(1-\tau _e(z_t)\) of the estate, where \(z_t\) denotes the value of the household’s stock of wealth at the end of period t. The rest of the estate is taxed away by the government. This specification of the joint age and endowment process implies that the transition probability matrix, \(\Gamma \), controls the demographics of the model economy, the lifetime persistence of earnings, their life cycle pattern, and their intergenerational persistence.

To specify the process on s we must choose the values of \((2J)^2+J\) parameters, of which \((2J)^2\) are the conditional transition probabilities and the remaining J are the values of the endowment of efficiency labor units. To reduce this large number of parameters, we impose some additional restrictions on matrix \(\Gamma \). To understand these restrictions better, it helps to consider the following partition of matrix \(\Gamma \):

Submatrix \(\Gamma _\mathcal{E\mathcal E}\) contains the household wage dynamics of working-age households that are still of working-age one period later, and we place no restrictions on it so we must choose the values of \(J^2\) parameters. Submatrix \(\Gamma _\mathcal{E\mathcal R}\) describes the transitions from the working-age states into the retirement states. We restrict this matrix to be \(\Gamma _\mathcal{E\mathcal R}= p_{e\varrho } I\), where \(p_{e\varrho }\) is the probability of retiring and I is the identity matrix. This is because we assume that every working-age household faces the same probability of retiring, and because we use only the last realization of the working-age shock to keep track of the earnings ability of retirees. Consequently, to characterize \(\Gamma _\mathcal{E\mathcal R}\) we must choose the value of only one parameter. Submatrix \(\Gamma _\mathcal{R\mathcal E}\) describes the transitions from the retirement states into the working-age states that take place when a retiree exits the economy and is replaced by a working-age descendant. The rows of this submatrix contain a two parameter transformation of the stationary distribution of \(s \in \mathcal{E}\), which we denote by \(\gamma _\mathcal{E}^*\). This transformation allows us to control both the life cycle profile of earnings and its intergenerational correlation. Intuitively, the transformation amounts to shifting the probability mass from \(\gamma _\mathcal{E}^*\) toward both the first row of \(\Gamma _\mathcal{R\mathcal E}\) and toward its diagonal.Footnote 4 Consequently, to characterize \(\Gamma _\mathcal{R\mathcal E}\) we must choose the value of the two shift parameters. Finally, submatrix \(\Gamma _\mathcal{R\mathcal R}\) contains the transition probabilities of retired households that are still retired one period later. The value of this submatrix is \(\Gamma _\mathcal{R\mathcal R}= p_{\varrho \varrho } I\), where \((1-p_{\varrho \varrho })\) is the probability of exiting the economy. This is because the type of retired households never changes, and because we assume that every retired household faces the same probability of exit. Therefore, to identify this submatrix we must choose the value of only one parameter.

To keep the dimension of process \(\{s\}\) as small as possible while still being able to achieve our calibration targets, we choose \(J=4\). Therefore, to characterize process \(\{s\}\), we must choose the values of \(J^2+J+4=24\) parameters.Footnote 5

2.2 Preferences and technology

We assume that households derive utility from consumption, \(c_t\ge 0\), and from nonmarket uses of their time, and that they care about the utility of their descendents as if it were their own utility. Consequently, the households’ preferences can be described by the following standard expected utility function:

where function u is continuous and strictly concave in both arguments; \(0<\beta <1\) is the time-discount factor; \(\ell \) is the endowment of productive time; and \(0\le h_t \le \ell \) is labor. Consequently, \(\ell - h_t\) is the amount of time that the households allocate to nonmarket activities.

Aggregate output \(Y_t\) depends on aggregate capital \(K_t\) and labor \(L_t\) through a constant returns to scale aggregate production function, \(Y_t = f\left( K_t,L_t \right) \). We choose a Cobb-Douglas production function with capital share \(\theta \). We assume that capital depreciates geometrically at a constant rate, \(\delta \), and we use r and w to denote the prices of capital and of the efficiency units of labor before all taxes.

2.3 The government sector

The government in our model economies taxes capital income, labor income, consumption, and estates, and it uses the proceeds of taxation to make real transfers to retired households and to finance an exogenous amount of government consumption.

Social security in our model economy takes the form of transfers to retired households, which we denote by \(\omega (s)\), and which are financed with a payroll tax. The inclusion of a social security system has important implications for our research questions. First, it reduces the size of the steady-state aggregate stock of capital.Footnote 6 Second, it plays an important role in helping us to replicate the large fraction of households who own very few or zero assets in the US.Footnote 7 Third, since public pensions are paid as lifetime annuities, it insures the households against the risk of living for too long, and therefore it reduces their incentives to save.

Our calibration procedure allows us to match the size of the average public retirement pension paid in the US and it ensures that the motives for saving in our model economy are quantitatively realistic. But pensions in our model economy are independent of contributions to social security and this feature qualifies the precision of our analysis in two ways. First, the overall amount of idiosyncratic risk in our model economy diminishes because the labor market history does not condition the retirement benefits. Second, we abstract from a potentially important reason to work, since in real world economies increasing the labor effort entitles the households to receive larger pension benefits.Footnote 8

The capital income taxes in the economy are described by the function:

where \(y_k\) denotes capital income. Of course, in the US economy different types of capital are taxed at different rates and receive different types of deductions. In order to simplify our model economy we consider just one type of capital good.Footnote 9

Labor income taxes are described by function \(\tau _\mathrm{l}(y_{a})\), where \(y_{a}\) denotes the labor income tax base. This tax is not used in the current US tax system. But it is part of the flat-tax reforms which we describe in Sect. 4.

Payroll taxes paid by firms are described by function \(\tau _{sf}(y_l)\), where \(y_\mathrm{l}\) denotes labor income, and payroll taxes paid by households are described by function \(\tau _{ sh}(y_l)\). Our choice for the payroll tax function is

This function approximates the cap on US payroll taxes.Footnote 10 To replicate the US Social Security tax code, we assume that the payroll taxes paid by the model economy households and firms are identical.

Household income taxes are described by the function:

where the definition of the tax base is \(y_{b}=y_{k}+y_\mathrm{l}-\tau _{k}-\tau _{sf}\). This is the function chosen by Gouveia and Strauss (1994) to model the 1989 US effective federal personal income taxes. Notice that both capital income taxes and payroll taxes paid by firms are excluded from the household income tax base both in the US personal income taxes and in our model economy household income taxes.

We assume that consumption taxes are proportional and that they are described by the function:

And finally, we assume that the estate tax function is

This function replicates the main features of the current effective estate taxes in the US.Footnote 11

Therefore, in our model economies, a government policy rule is a specification of \(\{\tau _{k}(y_k)\), \(\tau _\mathrm{l}(y_{a})\), \(\tau _{sf}(y_l)\), \(\tau _{ sh}(y_l)\), \(\tau _{y}(y_b)\), \(\tau _{c}(c)\), \(\tau _e(z)\), \(\omega (s)\}\) and of a process on government consumption, \(\{G_t\}\). Since we also assume that the government balances its budget every period, these policies must satisfy the following restriction: \(G_t + Z_t = T_t\), where \(Z_t\) and \(T_t\) denote aggregate transfers and aggregate tax revenues.

2.4 Market arrangements

We assume that there are no insurance markets for the household-specific shock. Instead, to buffer their streams of consumption against the shocks, the households in our model economy can accumulate wealth in the form of real capital. We assume that these wealth holdings, \(a_t\), belong to a compact set \(\mathcal{A}\). The lower bound of this set can be interpreted as a form of liquidity constraints, or as a solvency requirement.Footnote 12 We also assume that firms rent factors of production from households in competitive spot markets, which implies that factor prices are given by the corresponding marginal productivities.

2.5 The households’ decision problem

The individual state variables are the realization of the household-specific shock, s, and the value of the stock of assets, a.Footnote 13 The Bellman equation of the household decision problem is the following:

where function v is the households’ common value function. Notice that household income, which we denote by y, includes three terms: capital income, \(y_{k}=a\,r\), labor income, \(y_\mathrm{l}=e(s) \,h\,w\), and retirement pensions, \(\omega (s)\). Every household can earn capital income. Only workers can earn labor income. And only retirees receive retirement pensions. The household policy that solves this problem is a set of functions that map the individual state into the optimal choices for consumption, end-of-period savings, and labor hours. We denote this policy by \(\{c(a,s)\), z(a, s), \(h(a,s)\}\).

2.6 Equilibrium

Each period the economy-wide state is a probability measure, \(x_t\), defined over an appropriate family of subsets of \(S \times \mathcal{A}\) that counts the households of each type, and that we denote by \(\mathcal{B}\). In the steady state this measure is time-invariant, even though the individual state variables and the decisions of the individual households change from one period to the next.Footnote 14

Definition 1

A steady-state equilibrium for this economy is a household value function, v(a, s); a household policy, \(\{c(a,s)\), z(a, s), \(h(a,s)\}\); a government policy, \(\{\tau _k(y_k)\), \(\tau _l(y_a)\), \(\tau _{sf}(y_l)\), \(\tau _{ sh}(y_l)\), \(\tau _y(y_b)\), \(\tau _c(c)\), \(\tau _e(z)\), \(\omega (s)\), \(G\}\); a stationary probability measure of households, x; factor prices, (r, w); and macroeconomic aggregates, \(\{K,L,T,Z\}\), such that:

- (i)

Given factor prices and the government policy, the household value function and the household policy solve the households’ decision problem described in equations (6)–(10).

- (ii)

Firms behave as competitive maximizers. That is, their decisions imply that factor prices are factor marginal productivities \(r=f_1\left( K,L\right) -\delta \) and \( w=f_2\left( K,L\right) \).

- (iii)

Factor inputs, tax revenues, and transfers are obtained aggregating over households:

$$\begin{aligned}&K = {\displaystyle \int }\,a\,\mathrm{d}x, \ \ \ L = {\displaystyle \int }\,h(a,s)\;e(s)\,\mathrm{d}x, \ \ \ Z={\displaystyle \int }\,\omega (s)\,\mathrm{d}x\\ T= & {} {\displaystyle \int }[\tau _k(y_k)+\tau _l(y_a)+\tau _{sf} (y_l)+\tau _{ sh}(y_l)+\tau _y(y_b)+\tau _c(c)]\,\mathrm{d}x \\&\quad + {\displaystyle \int } {\mathbf {I}}_{s\in \mathcal {R}} \gamma _{s\mathcal{E}} \tau _e(z)\,z(a,s)\,\mathrm{d}x \end{aligned}$$where \({\mathbf {I}}\) denotes the indicator function, the definition of parameter \(\gamma _{s\mathcal{E}}\) is \(\gamma _{s\mathcal{E}}\equiv \sum _{s'\in \mathcal{E}} \Gamma _{s s'}\) and, consequently, \(({\mathbf {I}}_{s\in \mathcal {R}}\,\gamma _{s\mathcal{E}})\) is the probability that a retiree of type s exits the economy. Every integral in the four definitions above is defined over the state space \(S\times \mathcal A\).

- (iv)

The goods market clears: \(\displaystyle \int \,\left[ \, c(a,s)+z(a,s)\right] \,\mathrm{d}x +G = f\left( K,L\right) + (1-\delta )\,K\).

- (v)

The government budget constraint is satisfied: \(G+Z =T\)

- (vi)

The measure of households is stationary:

$$\begin{aligned} x(B)=\int _\mathrm{B}\left\{ \int _{S \times \mathcal{A}} \left[ {\mathbf {I}}_{z=z(a,s)}\,\,{\mathbf {I}}_{s\in /\mathcal{R}\vee s'\in /\mathcal{E}} +{\mathbf {I}} _{z=[1-\tau _e(z)] z(a,s)}\,\,{\mathbf {I}}_{s\in \mathcal{R}\wedge s'\in \mathcal{E}}\right] \Gamma _{ss'} \, \mathrm{d}x \right\} \mathrm{d}z\,\mathrm{d}s' \end{aligned}$$

for all \(B\in \mathcal{B}\), where \(\vee \) and \(\wedge \) are the logical operators “or” and “and”. This equation counts the households, and the cumbersome indicator functions and logical operators are used to account for estate taxation. We describe the procedure that we use to compute this equilibrium in Section C of the Appendix in the working paper version of the paper.

3 Calibration

Our model economy is characterized by 42 parameters (5 for preferences, 2 for production technology, 11 for government policy, and 24 for the joint process on the age of the households and on the endowments of efficiency labor units). To choose the values of these parameters we need 42 calibration targets. Of these targets, 6 are normalization conditions, and the remaining 36 are statistics that describe relevant features of the US economy. Seven of these calibration conditions uniquely determine the value of 7 of the model economy parameters. To determine the values of the remaining 29 parameters, we solve the system of 29 nonlinear equations that results from equating the values of the statistics of the model economy to those of their corresponding US targets. The details of the procedure that we use to solve this system can be found in Section C of the Appendix in the working paper version of the paper.

Model period The US tax code defines tax bases in annual terms. Since the income tax, the payroll tax and the estate tax are not proportional taxes, the obvious choice for our model period is one year. Moreover, the Survey of Consumer Finances, which is our main source of micro-data, is also yearly. We will take 1997 as our calibration year, which should serve as a representative pre-Great Recession year.

Normalization conditions The household endowment of disposable time is an arbitrary constant and we choose it to be \(\ell =3.2\). We also normalize the endowment of efficiency labor units of the least productive households to be \(e(1)=1.0\). Finally, since matrix \(\Gamma \) is a Markov matrix, its rows must add up to one. This property imposes four additional normalization conditions on the rows of \(\Gamma _\mathcal{E \mathcal E}\).Footnote 15

3.1 Macroeconomic and demographic targets

Ratios We target a capital to output ratio, K / Y, of 3.58, a capital income share of 0.376, and an investment to output ratio, I / Y, of 22.5%. We obtain our target value for the capital output share dividing $288,000, which was average household wealth in the US in 1997 according to the 1998 Survey of Consumer Finances, by $80,376, which was per household Gross Domestic Product according to the Economic Report of the President (2000) for the US in 1997.Footnote 16 Our target for the capital income share is the value that obtains when we use the methods described in Cooley and Prescott (1995) and we exclude the public sector from the computations.Footnote 17 To calculate the value of our target for I / Y, we define investment as the sum of gross private fixed domestic investment, change in business inventories, and 75% of the private consumption expenditures in consumer durables using data for 1997 from the Economic Report of the President (2000).Footnote 18

Allocation of time and consumption We target a value of \(H/\ell =33\) percent for the average share of disposable time allocated to working in the market.Footnote 19 For the curvature of consumption we choose a value of \(\sigma _1=1.5\). This value falls within the range (1–3) that is standard in the literature.Footnote 20 Finally, we want our model economy to replicate the relative cross-sectional variability of US consumption and hours. To this purpose, we target a value of \(cv(c)/cv(h)=3.5\) for the ratio of the cross-sectional coefficients of variation of these two variables.

The age structure of the population We target the expected durations of working-lives and retirement of the model economy households to be 45 and 18 years. These targets replicate the average durations of working-lives and retirement in the US.

The life cycle profile of earnings To replicate the life cycle profile of earnings of the US in our model economy, we target the ratio of the average earnings of households between ages 60 and 41 to that of households between ages 40 and 21. In the 1972–1991 period the average value of this statistic in the US was 1.303, according to the Panel Study of Income Dynamics.

The intergenerational transmission of earnings ability To replicate the intergenerational correlation of earnings of the US in our model economy, we target the cross-sectional correlation between the average lifetime earnings of one generation of households and the average lifetime earnings of their immediate descendants. Solon (1992) and Zimmerman (1992) measure this statistic for fathers and sons in the US, and they report that it is 0.4, approximately.

3.2 Government policy

In Table 1 we report the revenues obtained by the combined Federal, State, and Local Governments in the US in the 1997 fiscal year. To choose the parameter values of the tax functions in our model economy we must first allocate the US tax revenues to the tax instruments of our benchmark model economy. We choose the parameters of the model economy household income tax so that they collect the revenues levied by the US personal income tax, the parameters of the model economy capital income tax so that it collects the revenues levied by the US corporate income tax, and with the model economy payroll and estate taxes we do likewise. The remaining sources of government revenues in the US are sales and gross receipts taxes, property taxes, excise taxes, custom duties and fees, and other taxes. Added together, these tax instruments collected 7.09% of US GDP in 1997. In our model economy we allocate these revenues to the consumption tax.Footnote 21

To choose the parameters of the expenditure side of the government budget, we do the following: First, since the government of our model economy must balance its budget, we require that the output shares of government consumption and government transfers—the two expenditure items in our model economy—add up to 27.52%, which was the GDP share of total tax revenues in the US in 1997. Then we target a value for the transfers to output ratio in the model economy of 5.21%. This value corresponds to the share GDP accounted for by Medicare and by two-thirds of Social Security transfers in the US in 1997. We chose this target because transfers in our model economies are lump-sum, and Social Security transfers in the US economy are mildly progressive. This choice leaves us with a residual share for government expenditures to GDP of \(22.31(=27.52-5.21)\) which is our target for the G / Y ratio in our model economy.Footnote 22 We discuss the details of our choices for the various model economy tax function parameters in the paragraphs below.

Capital income taxes We choose \(a_1\), the capital income tax rate of function (1), so that the revenues collected by this tax in the benchmark model economy match the revenues collected by the corporate profit tax in the US economy.

Payroll taxes To characterize the payroll tax function described in expression (2), we must choose the values of parameters \(a_2\) and \(a_3\). In 1997 in the US the payroll tax rate paid by both households and firms was 7.65% each and it was levied only on the first $62,700 of gross labor earnings. This value was approximately equal to 78% of the US per household GDP. To replicate these values, in our model economy we make \(a_{2} = 0.0765\) and \(a_{3} = 0.78{\bar{y}}\), where \({\bar{y}}\) denotes output per household. These choices imply that the payroll tax collections in our model economy are endogenous, and that we can use them as an overidentification restriction.

Household income taxes To characterize the income tax function described in expression (3), we must choose the values of parameters \(a_4\), \(a_5\) and \(a_6\). Since \(a_4\) and \(a_5\) are unit-independent, we use the values reported by Gouveia and Strauss (1994) for these parameters, namely, \(a_4=0.258\) and \(a_5=0.768\). To determine the value of \(a_6\), we equate the tax rate levied on a value of income equal to average output per household in our model economy to the effective tax rate on GDP per household levied in the US economy. Again, these choices imply that the household income tax collections in our model economy are endogenous, and that we can use them as another overidentification restriction.

Estate taxes To characterize the estate tax function described in expression (5), we must choose the values of parameters \(a_7\) and \(a_8\). During the 1987–1997 period in the US the first $600,000 of the value of estates were tax exempt. This value was approximately equal to ten times the average value of GDP per household.Footnote 23 In our model economy we make \(a_{7}=10{\bar{y}}\), to replicate this feature of the US estate tax code. Finally, we choose the value of \(a_{8}\) so that the estate tax in our model economy collects the same revenues as the estate tax in the US.

Consumption taxes We choose the value of parameter \(a_{9}\) in the consumption tax function described in expression (4) residually, so that the government in our model economy balances its budget. Therefore, the consumption tax collections in our model economy are also endogenous, and they can be interpreted as a third overidentification restriction.

3.3 The distributions of earnings and wealth

The conditions that we have described so far specify a total of 27 targets. To solve our model economy we must choose the values of 42 parameters. Therefore, we add 15 additional targets: we use the 2 Gini indexes and 13 additional points form the Lorenz curves of the US distributions of earnings and wealth which we report in Table 4.Footnote 24

3.4 Calibration results

Our calibration procedure allows us to characterize the stochastic process of the endowment of efficiency labor units. As we will see below, we obtain a process with strong skewness, fat tight tail, and nonlinear dynamics. This process is not to be taken literally, since it is a black box that represents everything that we do not know about our model economy. However, its main features are consistent with recent empirical estimates by Arellano et al. (2017) and Guvenen et al. (2019).

In the second column of Table 2 we report the relative endowments of efficiency labor units, and in the third column the invariant measures of each type of working-age households. The endowments of workers of \(s=2\), \(s=3\), and \(s=4\) are, approximately, 3, 10, and 635. This means that, in our model economy, the luckiest workers are 635 times as lucky as the unluckiest ones. The stationary distribution shows that each period 85% of the workers are unlucky and draw states \(s=1\) or \(s=2\), and that only one out of every 1,567 workers is extremely lucky and draws state \(s=4\).

In the last four columns of Table 2 we also report the transition probabilities between the working-age states. Every row sums up to 97.78% plus or minus rounding errors. This is because the probability that a worker retires is 2.22%. The first three states are very persistent. Their expected durations are 25.7, 25.3 and 29.4 years. In contrast, state \(s=4\) is relatively transitory and its expected duration is only 7.6 years.

As far as the transitions are concerned, we find that a worker whose current state is \(s=1\) is more likely to move to state \(s=2\) than to any of the other states. Likewise, a worker whose current state is either \(s=2\) or \(s=3\) is most likely to move back to state \(s=1\). Only very rarely workers whose current state is either \(s=1\) or \(s=2\) will make a transition either to state \(s=3\) or to state \(s=4\). Finally, when a worker draws state \(s=4\), it is most likely that she will draw either state \(s=3\) or state \(s=1\) shortly afterward.

We report the values of every other parameter of our model economy in Table 3, and in Table 4 we report the statistics that describe the main aggregate and distributional features of the US and the benchmark model economies. These numbers confirm that overall our model economy succeeds in replicating the most relevant features of the US in very much detail.Footnote 25 We are particularly encouraged by our model economy’s ability to replicate the US fiscal policy ratios and the US distributions of earnings, income and wealth, since these two sets of targets are the main focus of this article. Recall that in our calibration exercise we have not targeted either the payroll tax collections, the household income tax collections, the consumption tax collections, or the statistics that describe the income distribution, and that all of these statistics can be considered to be overidentification restrictions.

4 The flat-tax reforms

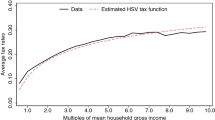

We study two families of flat-tax reforms: the consumption-based flat-tax reform originally proposed by Hall and Rabushka (1995) and an income-based flat-tax reform. In both cases we replace the household income tax with a flat tax on all labor income above a tax-exempt level, and the calibrated capital income tax with an integrated flat tax on capital income. The function that describes the labor income tax is

where the tax base is labor income net of social security taxes paid by firms, \(y_{a}=y_\mathrm{l}-\tau _{sf}(y_\mathrm{l})\), parameter \(a_{10}\) is the tax-exempt level of labor income, and parameter \(a_{11}\) is the flat-tax rate. The capital income tax function in the reformed economies is the same as the capital income tax function defined in Expression (1). The only difference is that in the consumption-based tax reforms investment expenditures are tax exempt and, consequently, the capital income tax base is capital net of depreciation income minus savings. Therefore, in these reforms \(y_k=r\,a -\left( a^{\prime }-a \right) \).Footnote 26 Since in every reform capital and labor income are taxed at the same marginal tax rate, we impose that \(a_{1}=a_{11}\). Finally, every flat-tax reform is designed to be revenue neutral and none of them changes the composition of public outlays. Therefore, in every flat-tax reform the values of T, G, and Z remain unchanged, and they are equal to their values in the benchmark model economy.

4.1 Investment expensing in flat-tax reforms

In this section we compare the allocations that obtain in the steady states of two flat-tax model economies that differ only in the fiscal treatment of investment expenditures. In the consumption-based flat-tax economy investment expenditures are fully deductible, and in the income-based flat-tax economy they are fully taxed.

The consumption-based flat-tax economy, which in this section we call \(E_\mathrm{C}\), is the standard flat-tax reform originally proposed by Hall and Rabushka (1995). As these authors suggested, its marginal tax rate on capital and labor income is 19%. And we choose the size of its labor income tax deduction to make the reform revenue neutral. This requires a labor income tax deduction \(a_{10}=0.3236\), which corresponds to 20% of output per household in the benchmark model economy or $16,000, approximately.

In the income-based flat-tax economy, which we call \(E_\mathrm{Y}\), we keep the 19% marginal integrated flat-tax rate, but since investment expenditures are not deductible, we change the labor income tax deduction to make the reform revenue neutral. In principle, the direction of this change could go either way. Taxing investment increases the base of the capital income tax. In partial equilibrium this would increase the capital income tax revenues and it would require a larger deduction in the labor income tax to make the reform revenue neutral. But in general equilibrium taxing investment reduces the capital stock. Therefore it also reduces aggregate output and the bases of both the capital and the labor income flat taxes. It turns out that this second effect dominates. And we find that the value of the labor income tax deduction that makes this reform revenue neutral is \(a_{10}=0.1805\), which is 45% smaller than the one that obtains in the consumption-based flat-tax reform, and which corresponds to approximately $8,924. This is because steady-state output in the income-based flat-tax reform is substantially smaller than in the consumption-based flat-tax reform, as we discuss below.

4.1.1 Macroeconomic aggregates and factor ratios

In Table 5 we report the main macroeconomic aggregates and factor ratios of our model economies. We find that the steady-state aggregate changes brought about by the consumption-based flat-tax reform are substantial. Steady-state output in model economy \(E_\mathrm{C}\) is 11% larger than in the benchmark economy, \(E_\mathrm{B}\). This increase in output is brought about by a very large increase in aggregate capital, of 35%. In contrast, the changes brought about in the aggregate labor input are small. Both total labor hours and the total labor input decrease by about 1%. We also find that the productivity of labor hours increases by approximately 13%, as a result of capital deepening.

There are two reasons that justify the increase in the capital stock. First, the consumption-based flat-tax reform eliminates the distortion in the intertemporal allocation of consumption, which encourages the households to save and to accumulate capital. Second, as we discuss below, the distribution of after-tax income becomes more unequal. This increases the need for precautionary savings and therefore it increases the size of the capital stock even further.

We find that the changes brought about by the income-based flat-tax reform are much smaller. As expected, taxing investment has large implications for the capital accumulation decision. Compared to the benchmark model economy, in the income-based flat-tax reform aggregate capital increases by 11.5%, which is only one third of the increase that obtains in the consumption-based reform. Still, the increase in the capital stock is not small.

There are two reasons for this increase. First, as in the consumption-based reform, there is an increase in the precautionary motive for savings. Second, the income-based flat-tax reform reduces the marginal capital income tax rates faced by the wealthy, and they increase the marginal capital income tax rates faced by the wealth poor. This is because in our benchmark economy capital income is taxed twice—once by the capital income tax and a second time by the household income tax—and because the rates on capital income of the household income tax are progressive. The aggregate effect of these changes is to increase capital accumulation because wealthy households are more concerned with after-tax returns and less concerned with precautionary motives than poor households.

The income-based flat-tax reform also brings about changes in the aggregate labor input that are very small. Consequently, aggregate output in this model economy is only 4% larger than in the benchmark economy, while in the consumption-based flat-tax reform it is 11% larger.

4.1.2 Expenditure ratios

In Table 6 we report the key expenditure ratios in the benchmark model economy and in the two reformed flat-tax model economies. Since the level of public expenditure, G, is the same in the three model economies, the G / Y ratios fall whenever output increases. Since both reforms bring about sizable increases in aggregate capital, the decreasing marginal returns to capital make the investment to output ratios increase and the consumption to output ratios fall. However, even though the C / Y ratios fall in both flat-tax reforms, it is important to highlight that in both of them aggregate consumption increases (see Column 4 in Table 6). This increase is about 4.5% larger in the consumption-based flat-tax reform than in the income-based flat-tax reform.

4.1.3 Fiscal policy ratios

In Table 7 we report the main fiscal policy ratios of the model economies. We have already mentioned that in both reformed model economies the government expenditures to output ratios are smaller than in the benchmark model economy. Moreover, the tax revenue to output ratios and the transfers to output ratios of these model economies are reduced in the same proportion.

The bottom 2 rows of Table 7 display the tax ratios relative to the output in the benchmark model economy. We observe that, as Hall and Rabushka (1995) had guessed, the labor income tax in the consumption-based flat-tax reform collects less revenues than the personal income tax of the benchmark model economy. This is also the case in the income-based flat-tax reform. The revenue losses are compensated by the higher revenues collected by all the other tax instruments. The lion’s shares of these revenues correspond to consumption taxes in model economy \(E_\mathrm{C}\) and to capital income taxes in model economy \(E_\mathrm{Y}\).

4.1.4 Earnings, income, and wealth inequality

In Table 8 we report the Gini indexes and the Lorenz curves of earnings, after-tax income, and wealth in the benchmark and in the reformed model economies. We find that the effects of the flat-tax reforms on earnings inequality are very small, but that both reforms bring about sizable increases in after-tax income inequality and in wealth inequality. The first result is not surprising since the three model economies have identical processes on the endowments of efficiency labor units.

The higher inequality in wealth is easy to understand because the marginal taxes on capital income for the wealthy are lower after the flat-tax reforms. And this gives rich households stronger incentives to accumulate capital. The inequality in after-tax income is larger in the flat-tax economies because of the increase in the inequality in the wealth distribution and because of the lower redistributive power of flat taxes.

When we compare both reforms, we find that consumption-based flat-tax reform creates more inequality than the income-based flat-tax reform. The Gini index of after-tax income in model economy \(E_\mathrm{C}\) is 0.550, and in model economy \(E_\mathrm{Y}\) it is only 0.532. These changes are brought about by changes the income shares earned by the households in both tails of the distributions. The shares earned by the households in the bottom two quintiles of model economy \(E_\mathrm{C}\) are 0.3 and 1.2 percentage points smaller than in model economy \(E_\mathrm{Y}\), and the share earned by the households in the top quintile is 1.6 percentage points larger. Finally, we find that the differences between the Gini indexes of wealth of both flat-tax reforms are smaller − 0.841 in model economy \(E_\mathrm{C}\) and 0.837 in model economy \(E_\mathrm{Y}\).

Interestingly, in Sect. 4.3, we show that, even though there is more after-tax income and wealth inequality in the steady state of model economy \(E_\mathrm{C}\), the consumption-based flat-tax reform results in a welfare gain which is equivalent to a 5.24% increase in consumption in every period and in every state. In contrast, we find that the income-based flat-tax reform results in a welfare loss which is equivalent to a 0.14% reduction in consumption.

4.2 Progressivity in consumption-based flat-tax reforms

In this section we compare the allocations that obtain in the steady states of three consumption-based flat-tax reforms. The first flat-tax reform is the least progressive of the three. In this model economy all labor income is taxed. Therefore the value of the labor income tax deduction is zero and \(a_{10}=0.0\). The integrated flat-tax rate that makes this reform revenue neutral is 15.3%. To keep this in mind we call this economy \(E_{15}\).

The second consumption-based flat-tax reform is the standard flat-tax reform proposed by Hall and Rabushka (1995) which we have discussed in the previous section. Its marginal tax rate on capital and labor income is 19%, and the labor income tax deduction that makes this reform revenue neutral is \(a_{10}=0.3236\), which corresponds to 20% of the benchmark model economy output per household, or approximately $16,000. To be consistent we have relabeled this model economy and we now call it \(E_{19}\).

The third consumption-based flat-tax reform is the most progressive of the three. In this model economy, we double the labor income tax deduction of model economy \(E_{19}\). Therefore, in this model economy \(a_{10}=0.6472\), which corresponds to approximately $32,000. The value of the integrated flat-tax rate that makes this reform revenue neutral is 24.7%, and we call this model economy \(E_{25}\).

4.2.1 Macroeconomic aggregates and factor ratios

In Table 9 we report the main macroeconomic aggregates and factor ratios of our three consumption-based flat-tax reforms. Relative to the benchmark model economy, we find that the three flat-tax reforms are expansionary. We also find that reforms generate large increases in the stock of capital—between 33 and 36%—and that the three reforms generate small changes in the labor decision. But while in model economy \(E_{15}\) both aggregate hours and the aggregate labor input increase, in model economies \(E_{19}\) and \(E_{25}\), these two variables decrease. When we compare the three reformed model economies with each other, we find that every statistic that we report in Table 9 is monotonic in the flat-tax rate. This behavior is consistent with the idea that higher marginal taxes create larger distortions.

But we find that the increases in the productivity of labor hours are larger in the reformed economies with higher flat-tax rates: 10.6% in model economy \(E_{15}\), 12.6% in model economy \(E_{19}\), and 15.2% in model economy \(E_{25}\). These increases in labor productivity are due to increases both in the labor to hours ratios, L / H, and in the capital to labor ratios, K / L—see the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth columns of Table 9.

By definition, the increases in the L / H ratios are the result of household hours being more correlated with the endowment of efficiency labor units. This tells us that as we move toward a more progressive flat-tax system households need to provide less self-insurance. Consequently, they accumulate less precautionary savings—and hence the stock of capital is lower—and they use less precautionary hours—and hence people work less, but labor hours become more correlated with productivity. This makes the allocations more similar to the ones that would obtain under complete markets.Footnote 27

The increases in the K / L ratios are ultimately due to the same reason: the reduction in hours reduces the aggregate labor input and, therefore, capital per efficiency unit of labor increases. These results lead us to conclude that the fixed deduction in labor income makes labor hours more productive, and that it improves the allocation of the work effort. In economies with higher flat-tax rates, people end up working less on average, but they work more when they are more productive.

Our results are surprisingly consistent with the findings of Ventura (1999). He considers two consumption-based flat-tax reforms with labor income tax exemptions equal to 20 and 40% of the income per household of his benchmark economy. The flat-tax rates that make his reforms revenue neutral are 19.1 and 25.2%, which are only slightly larger than the 19.0 and 24.7% rates of our model economies \(E_{19}\) and \(E_{25}\), which have similar deductions. Ventura (1999) finds that both flat-tax reforms bring about large output gains, 17 and 13%—these numbers are 11 and 9% in our comparable reforms. And he also finds that these gains are mainly the result of large increases in capital accumulation. These results are remarkably similar to ours in spite of some important differences between his model economies and ours. First, to proxy for the effective personal income tax rates, Ventura (1999) uses the statutory tax rates and income brackets. Therefore, in his benchmark model economy the marginal taxes rates of the personal income tax are higher than ours, and his flat-tax reforms bring about efficiency gains that are larger than ours. Second, households in Ventura (1999) lack altruistic motives for saving. And Third, Ventura (1999) largely understates the concentration of the earnings, income and wealth distributions.Footnote 28

4.2.2 Expenditure ratios

In Table 10 we report the key expenditure ratios in the benchmark model economy and in the three reformed flat-tax model economies. Since the flat-tax reforms are expansionary and the levels of government expenditures do not change, the G / Y ratios in the flat-tax model economies are smaller than in the benchmark model economy. The lower G / Y shares are compensated with large increases in the investment to output ratios, because the consumption to output ratios also decrease. These results are consistent with the large increases in the capital stock which we have discussed in Sect. 4.2.1.

We also find that aggregate consumption increases in the three consumption-based flat-tax reforms. The increase is largest in model economy \(E_{15}\) and it gets smaller as we increase the progressivity of the flat-tax system. This notwithstanding, we find that the differences in consumption and investment—and in their ratios to output—brought about by differences in the progressivity of the flat-tax reforms are small.

4.2.3 Fiscal policy ratios

In Table 11 we report the main fiscal policy ratios in the benchmark model economy and in the three reformed flat-tax model economies. In the three reforms total government revenues, T, government consumption, G, and total transfers, Z, do not change, and hence their ratios to output fall.

When we compare the changes in the composition of government revenues, we confirm that in every consumption-based flat-tax reform the labor income tax collects less revenues than the personal income tax of the benchmark model economy (see bottom 3 rows in Table 11). In contrast, payroll and consumption taxes collect more revenues in the three flat-tax model economies, and capital income taxes collect more revenues in model economies \(E_{19}\) and \(E_{25}\), but less in the model economy \(E_{15}\). The total revenues from the labor income tax, the payroll tax and the consumption tax are decreasing in the progressivity of the reforms, and the revenues from the capital income taxes are increasing in the progressivity of the reform.

Revenues from the consumption tax decrease with the progressivity of the reform because the consumption tax rate remains unchanged and aggregate consumption—which is the tax base—decreases as the flat-tax rates increase (see Table 10). The same is true for the payroll tax: the tax rate does not change, and the tax base, which is essentially aggregate labor income, decreases with the flat-tax rate.Footnote 29 The labor income tax revenues fall with the progressivity of the reforms because the tax base is lower for more progressive reforms due to both lower total labor income and higher labor income tax deduction.Footnote 30

Finally, the changes in the capital income tax are a bit more involved. Its aggregate tax base is

Compared to the benchmark economy the proportional flat-tax reform has less capital tax income. This is because the tax rates are very similar (15.3 against 14.6%) and the tax base is lower in the proportional tax flat-tax economy as the increase in aggregate output is much lower than the increase in aggregate capital (see Table 9). When we compare the consumption-based flat-tax reforms with each other, the capital income tax revenues increase with the more progressive reforms because the flat-tax rate is higher and the changes in the tax base are not too large.

4.2.4 Earnings, income, and wealth inequality

In Table 12 we report the Gini indexes and the Lorenz curves of earnings, income, and wealth of the benchmark model economy and of the consumption-based flat-tax reforms. The Gini indexes of before-tax income and wealth are higher in the three reformed economies and the Gini index of model economy \(E_{15}\) is also higher. Moreover earnings, before-tax income, and wealth inequality increase as the flat-tax reforms become more progressive. But the maximum differences between the Gini indexes of earnings, before-tax income, and wealth in the three model economies are small—9, 9, and 5 points per thousand. We conclude that the flat-tax reforms bring about increases in inequality and that, overall, the distributional role played by the progressivity of consumption-based flat taxes is small.

Earnings inequality increases as the flat-tax reform becomes more progressive because higher flat-tax rates and higher deductions increase the correlation between wages and work effort (see the discussion in Sect. 4.2.1). Since this implies that labor income becomes more volatile, households transfer income between periods using larger buffer stocks of precautionary savings to smooth their consumption profiles. This implies that wealth inequality also increases.

Perhaps more importantly, we find that consumption-based flat-taxes bring about large redistributions of income. So much so that the ranking of the Gini indexes of the after-tax income distributions is reversed. This means that after-tax income inequality is reduced as the flat-tax reforms become more progressive. Interestingly though, the two less progressive consumption-based flat-tax reforms exacerbate after-tax income inequality—in model economy \(E_{15}\) the Gini index income increases in 19 points per thousand after accounting for all income taxes and transfers, and in model economy \(E_{19}\) it increases by 9 percentage points.

Notice, however, that the increases in income and wealth inequality brought about by the flat-tax reforms do not necessarily imply welfare losses to risk-averse households because they are silent about their effects on the inequality in consumption and leisure. In Sect. 4.3, we show that all three consumption-based flat-tax reforms result in sizable welfare gains, and that these welfare gains increase as the reforms become more progressive.

4.3 Welfare

In the previous section we have reported that the consumption-based flat-tax reform with a 19% marginal rate results in larger aggregate output, consumption, and productivity than the model economy with the current US tax code. But after-tax income becomes more unequally distributed. We have also shown that a consumption-based flat-tax reform brings about higher output gains than an income-based flat-tax reform with the same flat-tax rate, but that it also results in higher increases in after-tax income and wealth inequality. Finally, we have also shown that as the consumption-based flat-tax reforms become more progressive, the aggregate gains become smaller but the inequality of after-tax income is also reduced (see Table 13 for a summary of these changes). Therefore, a policymaker who had to choose between any of these reforms would face different versions of the classical trade-off between efficiency and equality. Which one of these reforms results in a steady states with higher aggregate welfare? In this section we use a Benthamite social welfare function to answer this question.Footnote 31

4.3.1 Aggregate welfare changes

To carry out the welfare comparisons, we define \(v_\mathrm{B}\left( a,s,\Delta \right) \) as the equilibrium value function of a household of type (a, s) in the benchmark model economy, whose equilibrium consumption allocation is changed by a fraction \(\Delta \) every period and whose leisure remains unchanged. Formally,

where \(c_\mathrm{B}\left( a,s \right) \), \(h_\mathrm{B}\left( a,s \right) \) and \(z_\mathrm{B}\left( a,s \right) \) are the solutions to the household decision problem defined in expressions (6)–(10). Next, we define the welfare gain of living in the steady state of flat-tax economy \(E_i\), for \(i=15,19,25,Y\), as the fraction of additional consumption, \(\Delta _{i}\), that we must give to, or take away from, the households of the benchmark model economy so that the aggregate steady-state welfare in model economy \(E_i\) is the same as in economy \(E_\mathrm{B}\). Formally, \(\Delta _{i}\) is the solution to the equation

where \(v_{i}\) and \(x_{i}\) are the equilibrium value function and the equilibrium stationary distribution of households in the flat-tax model economy \(E_i\).

The consumption-based flat-tax reforms We find that the equivalent variation in consumption for the original Hall and Rabushka reform—model economy \(E_{19}\)—is 5.24% (see last column in Table 13). This means that, from a Benthamite point of view, the steady state generated by such a reform is largely preferred to the steady state under the current tax code. Indeed, we would need to increase consumption of every household by 5.24% in every period and in every state for the social planner to be indifferent between the steady-state allocation implied by the current US tax code and the steady-state allocation that results from the consumption-based flat-tax system of model economy \(E_{19}\). The consumption-based flat-tax system with no deduction in labor income—model economy \(E_{15}\)—generates a welfare gain equivalent to a 3.47% increase in consumption. And the consumption-based flat-tax system with a labor income tax exemption that is twice as large as the one in model economy \(E_{19}\), and with a 24.7 flat-tax rate—model economy \(E_{25}\)—generates a welfare gain that is equivalent to a 7.5% increase in consumption.

Therefore, the three consumption-based flat-tax reforms yield steady states that are preferred to the steady state implied by the current US tax code. Moreover, the most progressive consumption-based flat-tax reform is preferred in welfare terms to the two less progressive consumption-based flat-tax reforms, even though it brings about a smaller increase in output and consumption. Our results show that a Benthamite social planner is willing to give up these gains in efficiency to reduce the after-tax income inequality, which in model economy \(E_{25}\) is the smallest (see Table 13).

The income-based flat-tax reform The picture is very different for the income-based flat-tax reform. As we report in Table 13, when compared to the current tax code in the US, the revenue-neutral flat-tax reform with a 19% integrated flat-tax rate and full expensing of investment—model economy \(E_\mathrm{Y}\)—increases aggregate output, consumption, and hours, but by a smaller amount than any of the three consumption-based reforms. The reformed tax code also increases after-tax income inequality. The size of this increase in inequality is such that it more than compensates the efficiency gains and, from the point of view of a Benthamite social planner, its new steady-state results in an average welfare loss which is equivalent to a 0.14% reduction in consumption. This welfare loss is in contrast to Conesa and Krueger (2006), who find that a flat-tax with a marginal rate of 17% and a fixed deduction in labor income would yield, for an unborn household, the maximum welfare gain across all possible parametric tax reforms of a Gouveia–Strauss tax function.Footnote 32

4.3.2 A decomposition of the aggregate welfare changes

To improve the understanding these results, it is useful to decompose the equivalent variation in consumption discussed above. To this purpose, we define two auxiliary measures of the equivalent variations in consumption for each reform. First, we compute the equivalent variation in consumption that makes the households indifferent between the benchmark model economy \(E_\mathrm{B}\) and the flat-tax model economy \(E_{i}\) ignoring the changes in the equilibrium distribution of households. We denote this variation by \(\Delta ^{a}_{i}\), and we define it as follows:

Notice that in this expression we calculate the aggregate welfare of the reformed model economies using their equilibrium price vectors, \((r_{i},w_{i})\), and the equilibrium stationary distribution of the benchmark model economy.

Second, we compute the equivalent variation in consumption that makes the households indifferent between the benchmark model economy \(E_\mathrm{B}\) and the reformed model economies \(E_{i}\) ignoring both the changes in the equilibrium distributions of households and the changes in the sizes of the economies. We denote this variation by \(\Delta ^{b}_{i}\), and we define it as follows:

Notice that now we calculate the aggregate welfare of the reformed model economies using both the equilibrium stationary distribution and the equilibrium price vector of the benchmark model economy.

These two equivalent variations allow us to decompose the total equivalent variation that we have defined in Expression (13) as follows:

The first term of Expression (14) measures the welfare changes that are due to the reshuffling of resources between the households and it ignores both the general equilibrium effects of the reforms and the changes in the distributions of households. The second term measures the welfare changes that are due to the general equilibrium effects of the reforms only. And the third term measures the welfare changes that are due to the changes in the distributions of households only.

The consumption-based flat-tax reforms In the first three rows of Table 14 we report this decomposition for our three consumption-based flat-tax reforms. We find that, the original (Hall and Rabushka 1995) reform—model economy \(E_{19}\)—yields welfare gains (see Column \(\Delta _{i}\)), even when we disregard the distributional and general equilibrium changes that it brings about (see Column \(\Delta ^{b}_{i}\)). These gains are sizeably larger in the more progressive consumption-based flat-tax reform—model economy \(E_{25}\). In contrast, the purely proportional consumption-based reform—model economy \(E_{15}\)—results in a welfare loss. These welfare changes are the direct consequence of the redistribution of the tax burden, and of the new individual allocations of consumption and leisure that the flat-tax systems generate. The welfare gains in model economies \(E_{19}\) and \(E_{25}\) result from the reduction of the tax burden on poor households through the fixed deduction in the labor income tax, which is absent in model economy \(E_{15}\).

When we consider the general equilibrium effects brought about by the change in prices, the sign of the welfare change is positive for the three consumption-based flat-tax reforms (see Column \(\Delta ^{a}_{i}-\Delta ^{b}_{i}\)). These welfare changes include an aggregate and a distributional component. The aggregate component is the result of the efficiency gains and losses that result from the new aggregate values of consumption and leisure. The distributional component is the result of the change in relative prices: the large increases in the capital to labor ratio increase wages and reduce the interest rates. Consequently, they shift income from capital owners to workers. Not surprisingly the general equilibrium effects are larger for the less progressive consumption-based flat-tax reforms that bring about larger gains in output and consumption (see the second and third columns of Table 13).

Finally, the three new equilibrium distributions of the consumption-based flat-tax reforms result in aggregate welfare gains (see Column \(\Delta _{i}-\Delta ^{a }_{i}\)). These welfare gains arise because these reforms put more households in points in the state space that have a higher utility.

The income-based flat-tax reform Once again, the picture is very different for the income-based flat-tax reform (see the last row of Table 14). We find that the reshuffling of the tax burden toward poorer households brought about by this reform creates a welfare loss that is not compensated by the welfare gains that result from the increases in efficiency. The labor income tax deduction in this reform is small, and a large share of the tax burden goes to households with a high marginal utility of consumption. Moreover, the distributional changes brought about by this reform also result in a small welfare loss.

4.3.3 Welfare changes by household types

Next, we look at the welfare gains and losses for different types of households. We compare the benchmark model economy and model economy \(E_{15}\). We do this for the sake of brevity and because this reform is the one that results in the smallest welfare gains. We conjecture that qualitatively our results would not change in the more progressive consumption-based reforms. And that quantitatively the welfare changes would be larger.

In our model economies there are as many household types as there are \(\left\{ a,s \right\} \) pairs in the individual state space. To calculate the welfare gains at each point in the state space, \(\Delta _{15}\left( a,s \right) \), we solve the following equation,

In Fig. 1 we report the averages of these measures of the individual welfare gains for various groups of households.

The wealth sorting In Panel A of Fig. 1 we sort the households by wealth and we average the welfare gains of the households in increments of five percentile points of the wealth distribution. It turns out that the welfare gains are larger for the asset-poor households and that they are decreasing in wealth. This reduction in welfare is not monotonic because as households become wealthier the share of households with different labor market shocks changes. But nonetheless, we find that the welfare changes are positive for the households in the bottom 65% of the wealth distribution.

These results may seem puzzling since the marginal tax rates of the personal income tax in model economy \(E_\mathrm{B}\) are progressive and both the marginal and the average labor income tax rates of model economy \(E_{15}\) are flat, because in model economy \(E_{15}\) there is no tax-exempt level of labor income. But there are two reasons that justify these results. First, the expensing of net savings, that is a part of every consumption-based flat-tax system, benefits the asset poor. When households with low assets get a good labor market opportunity they start accumulating resources, and the consumption-based taxation makes this capital accumulation tax exempt. Conversely, when asset rich households get a bad labor market shock they start to deplete assets in order to smooth their consumption, and this makes them pay higher taxes because all income obtained from dissaving is taxed. In a sense, the tax exemption of savings contains a strong redistributive component by helping wealth poor households escape from poverty, in exchange of the higher taxes paid by the households who run down their assets.

The second reason behind the welfare gains of asset-poor households are the general equilibrium effects of this flat-tax reform. Model economy \(E_{15}\) has a larger capital stock than the benchmark model economy and, hence, its wage rate is higher and its interest rate is lower. These differences in prices benefit the asset poor, who are intensive in labor income, and harm the asset rich, who are intensive in capital income.

In Panels B and C of Fig. 1 we first sort the households according to the realizations of the idiosyncratic shock, s, and then we rank them by wealth. This allows us to rank the households according to their two state variables. In Panel B we plot the welfare changes for the four types of workers, and in Panel C for the four types of retirees. Panel B clearly shows that the welfare gains of the workers are decreasing in wealth and increasing in labor market opportunities. Households with good labor market shocks benefit from the reduced taxes on capital and, since they tend to save more for a given level of assets, they also benefit from the tax exemption of savings.

The retirees are dissavers and large shares of their income come from capital sources. These are two important reasons that make them loose with the reform. Recall that the tax exemption on savings results in a larger tax burden when savings are negative. Moreover, the reduction in the interest rate reduces the income of the asset holders. And as households become wealthier these effects become larger. On the other hand, households in our model economy, and of course the retirees, are altruistic toward their offspring. The average duration of retirement is 17 years, and the average working life of the working-age household that will replace it is 45 years. Therefore, the welfare gains of the retirees contain part of the welfare gains of the workers, and they may more than compensate for their own welfare losses.

Panel C of Fig. 1 shows that for shocks \(s=5\), 6, or 7 the welfare gains decrease with wealth. They are positive for asset-poor retirees because they take into account the welfare gains of their asset-poor kids. In contrast, for shock \(s=8\), the welfare gains of retired households increase with wealth. This is because retirees of this type are very wealthy. And for sufficiently high asset holdings, the welfare gains of the reform increase with wealth because wealthy households benefit from not having to pay the large marginal taxes on capital income of the benchmark model economy.

The after-tax income sorting Next we sort the households according to their after-tax income, and we discuss the welfare gains of the income rich and of the income poor. In Panel D of Fig. 1 we show that the households in the bottom 20% of the after-tax income distribution benefit from the flat-tax reform. These households are wealth poor and their labor market productivity is low. The welfare changes for the households in the top 80% of the after-tax income distribution are not monotonic. This is because after-tax income increases with both labor income and wealth. In Panels E and F of Fig. 1 we sort the households according to their after-tax income but conditioning on the realization of the household-specific shock. In contrast to what we found in the wealth sorting, we find that the welfare gains of workers are increasing in income. This is consistent with the fact that conditional on wealth, welfare gains increase with the labor market shock, and it is a consequence of the large role played by earnings in the sorting of households by disposable income.

The value sorting It is hard to decide whether the tax reform benefits the poor sorting the households according to their wealth or according to their current after-tax income. This is because permanent income is a function both of financial wealth and of human wealth. Alternatively, we also rank households by their value function, as it reflects the expected lifetime value given their individual state, (a, s). In Panel G of Fig. 1 we plot the welfare changes brought about by the less progressive flat-tax reform sorting the households according to their values. We find that the households in the bottom 35% of the distribution of values benefit from this reform. This result is similar to the results that we obtained for the wealth and the after-tax income rankings. The welfare changes for the households in the top 65% of the distribution of values are nonmonotonic, and while some of them experience welfare gains after the reform, others experience welfare losses. The reason that justifies these nonmonotonicities is that the reform treats differently the various ways of obtaining utility—through high assets holdings or through good labor market shocks. In Panels H and I of Fig. 1 we plot the welfare gains of the value sorting, conditioning first on the realizations of the shock. The plots are identical to those in Panels B and C because the values turn out to increase monotonically with the assets holdings, after we condition on the realizations of the shock.

5 Concluding comments