Abstract

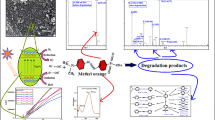

The overall effectiveness of a photocatalytic water treatment method strongly depends on various physicochemical factors. Superparamagnetic photocatalysts have incomparable advantage of easy separation using external magnetic fields. So, the synthesis of efficient superparamagnetic photocatalysts and the development of a deep understanding of the factors influencing their catalytic performances are important. Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 (x = 0, 0.5, 1) ferrite nanospheres were synthesized by the solvothermal route. The reduction of Cr(VI) and degradation of methyl orange (MO) impurities were carried out in single- and binary-component system under visible light irradiation. The adsorption experiments were done by the catalyst in the water solution containing the impurities. The magnetic and optical properties were studied by VSM and UV–Vis analysis. The nature of porosity was investigated using the BET method. 3D nanospheres of diameter about 5–10 nm were fabricated. The binary-contaminant system exhibited synergetic photocatalytic effect (80% improvement in activity rate) against the nanoparticles. The corresponding mechanism is discussed. CoFe2O4 exhibited better adsorption, photocatalytic and magnetic separation efficiency due to its higher surface area (50% higher), narrower band gap (25% lesser), smaller crystallite size, a strong magnetic strength (51.35 emu/g) and meso–macro hierarchical porous structure. The adsorption of Cr(VI) and MO can be approximated to the Langmuir and Freundlich model, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water contamination caused by heavy metal ions and organic dyes is one of the most severe problems of the industrialized modern world. Among the various heavy metal ions, hexavalent chromium Cr(VI) is reported as very toxic, carcinogenic and highly soluble, and is widely present in water resources. The oxidation state of chromium determines its toxicity. Cr(III) is less toxic compared to hexavalent chromium ion. So the procedures for efficient catalytic reduction of Cr(VI) metal ion hold much significance (Jacobs and Testa 2004). Methyl orange (MO) is a hazardous anionic organic dye commonly found in effluents from industries such as paper, plastic, rubber, paint and textile (Gurses et al. 2016). A variety of methods have been utilized for the removal of contaminants from water. Photocatalysis has emerged as one of the technologies for the removal of environmental contaminants in recent years (Qu et al. 2013; Fresno et al. 2014; Nanakkal and Alexander 2017). In the realistic case, because of human activity, the inorganic heavy metal ions and organic pollutants subsist together in surface water sources (Ali 2012). So, studies on the simultaneous photocatalytic degradation of mixed pollutant water systems and developing knowledge of its adsorption mechanism are of much relevance. Diverse photocatalysts have been explored for the photocatalytic degradation of MO (Cai et al. 2016; Singh et al. 2015) and Cr(VI) (Ali and Mostafa 2015) contaminants.

Spinel ferrites acquire matchless physical and chemical properties including tunable shape and size, elevated specific surface area, fresh active sites, remarkable chemical stability, etc. They can also be modified or functionalized for a particular application. The size reduction of ferrites below a critical size leads to a novel useful phenomenon—superparamagnetism. Being superparamagnetic in nature, they do not keep hold of magnetization prior to and after the removal of the magnetic field—therefore diminishing the particle aggregation, critical for the availability of photocatalytically active sites on the surface. Also, it can be efficiently separated from the system after the photocatalytic process (Makovec et al. 2012; Tang and Lo 2013). Ferrite nanoparticles hold a huge potential for water purification applications that necessitate high adsorption efficiencies, magnetic separation capacity and speedy kinetics (Reddy and Yun 2016).

The quest for newer geometries of ferrites is an active field of investigation (Abbas et al. 2014; Cao et al. 2014). Tweaking the morphology, shape and size of ferrite nanostructure for a particular purpose continues to be a complex task to date. 3D materials with porous nature have great significance in the field of photocatalysis, owing to their high surface area and superiority in the transport of reactant molecules. The solvothermal method is an effective technique for the preparation of nano ferrites, since it can produce monodisperse, narrow particle size distribution and offers a variety of morphologies.

Among ferrites, cobalt-substituted zinc ferrite has received much significance due to its visible light absorption capacity and excellent chemical stability (Abbas et al. 2014; He 2012). Literature shows some reports on the applicability of solvothermal methods for the synthesis of cobalt–zinc ferrite nanoparticles (Reddy et al. 2015; Hou et al. 2010). Fan et al. (2012) reported for the first time the visible light-induced photocatalysis on dye using Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 nanoparticles. In this report, the solvothermal method is used for the synthesis of 3D spherical ferrite nanospheres of diameter less than 10 nm. The ZnFe2O4 and CoFe2O4 photocatalysts have been explored in methyl orange degradation in its single-component impurity system (Cai et al. 2016). The photocatalytic degradation studies on the mixture of impurities (binary or ternary) using different photocatalysts is an emerging area of research (Liu et al. 2015a, b. For the real-world implementation of photocatalysis applied to the simultaneous removal of hazardous components from water, a deeper understanding of the photocatalytic material interface is crucial.

Considering all the above aspects, this study attempted to emphasize the synthesis and formation of Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 (x = 0, 0.5, 1) 3D nanosphere and investigated it as a bifunctional material, i.e., as a magnetic nanoparticle and a photocatalyst. This paper also tries to address the need to understand the catalytic mechanism, adsorption mechanism, microstructural details desirable for improved photocatalytic performance and factors determining synergetic catalytic degradation. In this way, this work provides a promising approach to provide a platform for the understanding of photocatalytic activity in a binary-impurity system.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 (x = 0, 0.5, 1) nanoparticles

Ferrite nanoparticles were obtained by a solvothermal method using ethylene glycol (99%) as the solvent. The nitrates of Co, Zn and Fe, viz., Co (NO3)2·6H2O (97%), Zn (NO3)2·6H2O (96%) and Fe (NO3)3·9H2O (98%), depending on the desired relative composition of Zn2+ and Co2+ in the ferrite were dissolved in ethylene glycol. The solution was mixed with polyethylene glycol (PEG; 98%, added in drops) and sodium acetate (98%). The reaction mixture was stirred for 10 min. The resultant mixture added with urea (99.5%) was stirred vigorously for 30 min and heated in an autoclave at 180 °C for 12 h. The PEG, sodium acetate and urea were intended to act as surfactants.

Characterization of nanoparticles

The crystallographic studies on the synthesized Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 nanoparticles were carried out by X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku-600) using Cu Kα radiation. The morphology of the samples was investigated using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (Jeol JEM 2100). Elemental analysis of ferrite nanoparticles was performed using ZEISS GEMINI SEM 300 coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). UV–Vis spectroscopic studies of the nanoparticles were done using JASCO V-550 spectrometer. The photoluminescence (PL) study was carried out using Perkin Elmer LS55 spectrometer. The magnetic properties were measured using a vibrating sample magnetometer DMS 1660 VSM at room temperature. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface analysis was performed using Micromeritics Tristar II 3000.

Photocatalytic performance tests

The photocatalytic experiment was performed under three different contaminant protocols: (i) with MO only (10 mg/L, pH = 7.36), (ii) with K2Cr2O7 only (10 mg/L, pH = 5.36) to provide Cr(VI) and (iii) a mixture of impurities (10 ppm each, pH = 5.80) viz., MO and K2Cr2O7. In all the experiments, 50 mg of the photocatalyst was suspended in 97 ml of the impurity solution. A 500 W halogen lamp was used as the source and the photocatalytic experiments were done under visible light region (illuminance of 70,000 lx). Preceding the irradiation, the suspensions were stirred in the dark for 60 min to accomplish adsorption–desorption equilibrium. 3 mL of dispersion was withdrawn at an equal interval of time and the catalyst was immediately separated with the help of an external magnet for performing UV–Vis analysis. The standard colorimetric technique using diphenylcarbazide reagent was adopted for the estimation of chromium impurity. The change in concentration of methyl orange and chromium ion due to the synthesized magnetic photocatalyst was estimated by monitoring the absorbance at 460 nm and 540 nm, respectively, with the help of UV–Vis spectrometer.

Results and discussions

Structural characterization

Figure 1a–c shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra of Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 (x = 0, 0.5, 1: denoted-ZFO, CZFO and CFO, respectively) along with Rietveld refinement. All the peaks in the XRD were identified to be of the AFe2O4 spinel type (A = Zn, Co) crystal with Fd-3 m cubic symmetry. The complete XRD had a good match with JCPDS file no: 01-089-7412. The average crystallite sizes of the nanoparticles calculated based on Scherrer formulae and lattice parameters evaluated using Rietveld refinements are shown in Table 1. The lattice parameter was found to slightly decrease with the increase of Co content. Thus, the data roughly obey Vegard’s law (Denton and Ashcroft 1991). This dependence could be attributed to the smaller radius of the Co cation (0.72 Å) than the Zn cation (0.82 Å).

A general shift in the peak position with the change in Zn2+ content can be noticed in the XRD pattern (Supplementary Fig. S1). This can be attributed to a change in lattice parameter (in turn related to ionic radius) of Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 nanoparticles. EDAX substantiated the formation of pure ferrite nanoparticles without the trace of any extra elements.

DRS-UV–Vis analysis

The Tauc plot evaluated based on the diffuse reflectance UV–Vis spectra of Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 is shown in Fig. 2. Here, the values (αhν)2 are calculated based on Kubelka–Munk function (F(R)), where α = (1 − R)2/2R, α is the absorption coefficient and R is the diffuse reflectance. The band gap energy values estimated for Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 using the Tauc plot are 2.07, 1.97 and 1.59 eV, respectively, for x = 0, 0.5 and 1.

The reduction in band gap energy with cobalt doping is caused by the sp–d exchange interaction between the band electrons of spinel ZnFe2O4 and the localized d-electrons of Co2+ions (Manikandan et al. 2013a). This causes the formation of sub-bands within the energy band gap. The merging of the sub-bands with the fine levels of the conduction band results in a continuous band. In addition, the blueshift with cobalt content can also be ascribed to (i) the decrease in the lattice constant (Singh et al. 2015; Manikandan et al. 2013b) and (ii) the creation of additional sub-band gap energy levels induced due to the surface and interface defects in the synthesized nanoparticles (Manikandan et al. 2014).

Morphological characterization

The TEM images of CZFO are shown in Fig. 3. A control in size, shape and morphology of nanoparticles has great significance in the field of catalysis. The choice of the combination of surfactants can play a critical role in deciding the morphology of the nanoparticles. From the TEM micrographs, the nanoparticles obtained were found to be sphere like and uniformly distributed. The diameter of the particles was found to be in the range 5–10 nm.

The mechanism of formation of CZFO nanospheres

The formation of the CZFO entity can be described as follows: The nitrate ions obtained from the cobalt, zinc and ferric nitrates in the reaction mixture undergo chelation with ethylene glycol (used as the solvent) to form metal alkoxides (Wang et al. 2010). The second step is the decomposition of metal Co(II), Zn(II) and Fe(III) alkoxides releasing CO2 and H2O to form CZFO crystallites. The primary crystallites of CZFO are formed in the early stages of nucleation. The nucleation is followed by growth without nucleation, resulting in monodispersed nanocrystals. The nanocrystals aggregate to form spherulite in the presence of surfactants. The degree of aggregation of particles augmented by surfactants influences the morphology and microstructure of metal oxides. According to the von Weimarn theory (Barlow et al. 2004), the development of nanosphere by the Ostwald ripening process (Mou et al. 2010; DavilaIbanez and Salgueirino 2013) involves differential diffusion and coalescing of the small spaces to form large structures. The above mechanism for the formation of Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 nanospheres is schematically represented in Fig. 4.

Superparamagnetism

Magnetic hysteresis loop of the particle is an S-like curve (Fig. 5), and the saturation magnetization is found to be increased with increase in cobalt content. The saturation magnetization value of the ZFO, CZFO and CFO samples is found to be 27.44, 38.90 and 51.35 emu/g, respectively. The observed saturation magnetization of the Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 samples is sufficient for their magnetic separation from a typical water purification system. The magnetic coercivity and remnant magnetization are noticed to be nearly zero, indicating an absence of residual magnetization upon removal of an external magnetic field. Thus, the Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 samples show the targeted superparamagnetism—very much relevant for magnetic separation of the catalyst after water purification (Fig. 6).

Photocatalytic experiments

Removal of M.O. and Cr(VI) in their respective single-component systems

The photocatalytic activity of the Cr(VI) reduction and methyl orange oxidation with ZFO, CZFO and CFO photocatalysts were investigated in their single- and binary-component system. The time-dependent degradation curves of both the analytes in the single-impurity system are illustrated in Fig. 7a, b. The photocatalytic degradation data can be modeled to a pseudo-first-order reaction (exponential regression) equation:

Photocatalytic degradation of a Cr(VI) in single-impurity system, b MO in single-impurity system, c Cr(VI) in binary-impurity system and d MO in binary-impurity system over Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 (x = 0, 0.5, 1) catalysts under visible light irradiation. The solid line shows fit to determine photocatalytic reaction rate (k) using the pseudo-first-order reaction equation

Here, C0 is the initial concentration, C is the concentration at time t, and k is the degradation rate constant. The rate constants (k) thus obtained are plotted as blue colored bars in Figs. 8 and 9. As noticed, the k value is dependent on the type of impurity. The reason is that photocatalytic degradation reaction mechanisms are different in methyl orange and chromium. Among all the ferrite samples, CFO exhibits the maximum activity of the Cr(VI) reduction and methyl orange degradation under visible light illumination. Thus in the single-contaminant system, the degradation rate enhanced with the increase in cobalt content.

Effect of MO and Cr(VI) adsorption in the binary-impurity system

Cr(VI) and MO equilibrium adsorption on the photocatalysts was performed at their natural pH 5.35 and 7.36, respectively, under the same conditions employed in photocatalytic experiments. The percentage amount of Cr(VI) adsorbed on the ferrites, both in the presence and in the absence of MO, is shown in Fig. 10. The extent of Cr(VI) and MO adsorption on all the ferrites was lower in the binary-impurity system, signifying the competitive adsorption of Cr(VI) and MO impurities. The higher surface area of the ferrite nanoparticles has a significant role in the extent of adsorption in the binary-impurity system. A similar competent adsorption mechanism can be inferred in the MO equilibrium adsorption plot (Fig. 11) also.

Synergetic photocatalysis of Cr(VI) reduction and methyl orange oxidation

Photocatalytic (PC) experiments were performed with Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 photocatalyst in a solution with the simultaneous presence of Cr(VI) and MO impurities. The binary-component impurity solution had the same concentration of Cr(VI) and MO as in the case of the single-impurity system (10 ppm each). Also, the PC experiments were performed under the same physical conditions including light intensity. The time-dependent degradation curves of both the components in the binary-impurity system are shown in Fig. 7c, d. The k values evaluated separately for Cr(VI) and MO impurities in the binary system are plotted as red colored bars in Figs. 8 and 9. As one can notice, compared to the single-component system, the photocatalytic degradation rates of Cr(VI) and MO increased in the binary system. It can be inferred that in the binary system, simultaneous Cr(VI) reduction and methyl orange oxidation promote the degradation rates of each other. Here, the mechanism can be understood in terms of three independent steps. (i) Methyl orange is an organic dye and its oxidation needs photogenerated holes. Thus, the presence of methyl orange could scavenge the photogenerated holes from the ferrites, suppressing the electron–hole recombination and accelerating the photoreduction of Cr(VI) by the photogenerated electrons. The hole scavenging role of MO was investigated using photoluminescence spectroscopy. The experiment was performed at an excitation wavelength of 200 nm to capture the PL results for CoFe2O4. The spectra were taken on a fixed concentration of CFO solution in water and repeating the experiment in the same catalyst concentration with MO. As seen in Fig. 12, the clear decline in the intensity of the PL spectrum for CFO in the presence of MO indicates the significant reduction in charge recombination in CFO. This substantiates that MO act as a scavenger for photogenerated holes from the ferrites. The scavenging leads to enhanced availability of electrons for catalytic reduction on Cr(VI). (ii) When irradiated with light, MO itself absorbs the photons and gets excited. The excited MO can transfer the electrons to Cr(VI) ions through the conduction band of the ferrites providing additional electrons in turn, leading to an enhanced reduction of chromium. (iii) Cr(VI) is a strong oxidant which also contributes to the degradation of anionic dye (Liu et al. 2015b). The synergetic role played by the strong oxidizing nature of Cr(VI) is demonstrated in Fig. 13. As seen in the figure, after 60 min irradiation, the degradation of MO is enhanced from 3 to 18% by the sole contribution of Cr(VI). The presence of catalyst CFO improved the degradation of MO to 98%. The O2˙¯are formed by the reduction of adsorbed oxygen on ferrite in contact with the electron. It is reported that O2˙¯could support the Cr(VI) reduction (Hu et al. 2014). Thus, the co-operative photocatalysis of the Cr(VI) reduction and MO oxidation could quickly utilize the photogenerated electrons and holes, which enhances the photocatalytic activity. The pathway for photocatalysis of Cr(VI) reduction and MO degradation using ferrite catalysts is illustrated in Fig. 14.

Photocatalytic mechanism

The possible paths of photocatalytic mechanism in the Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 ferrite photocatalyst under visible light irradiation is described in Eqs. (1)–(11):

Recyclability tests

The recyclability experiments were performed for six cycles. Removal efficiencies with CoFe2O4 toward MO and Cr(VI) in the binary solution are shown in Fig. 15. Even after six cycles, the catalyst provides around 90% of the degradation efficiencies of the first cycle. The experiments point to superior recyclability of the catalyst.

Adsorption equilibrium study

The adsorption isotherm helps to identify the manner in which the adsorbate is distributed between the solid phase and liquid phase and when at equilibrium. Isotherms are considered as the finest approach for a theoretical study of adsorption. Isotherms point out the nature of the interaction between the adsorbate and adsorbent. The Langmuir model and Freundlich model are widely employed for inquiring the nature of adsorption (Wang et al. 2012). The Langmuir model presumes monolayer coverage on a homogeneous surface (Jia et al. 2012). The Freundlich model is usually used to describe the adsorption characteristics for a heterogeneous surface (Kaur et al. 2015). Adsorption tests were carried out by stirring 50 mg of catalysts in 97 mL of chromium and MO impurity solutions separately. Quantity of impurities adsorbed by the nanospheres after treatment for 60 min were calculated. The linear form of the equations for the models can be expressed as follows:

Equations (12) and (13) correspond to Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms, respectively. Here, qe is the amount adsorbed at equilibrium (mg/g), Ce is the equilibrium concentration (mg/L), b is related to equilibrium constant (L/mg), and qm is the Langmuir monolayer adsorption capacity (mg/g). Kf roughly represents the Freundlich adsorption equilibrium constant associated with the adsorption capacity and n represents the adsorption intensity described as the distribution coefficient.

Adsorption isotherms with different initial concentrations of Cr(VI) and MO onto ZFO, CZFO and CFO powders are illustrated in supplementary figures Fig. S2a, b. All isotherm plots (Fig. S2a, b) fit well with adsorption isotherm equations and therefore Eqs. 12 and 13 were applied to simulate and understand the nature of adsorption.

Supplementary figures Fig. S3a, b represents the fit between the experimental data and the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms model for Cr(VI) adsorbate. The isothermal constants and the linear regression coefficients obtained from the experimental data and the related results for Cr(VI) are shown in Table S1. The higher regression coefficient R2 (see table S1) from Langmuir isotherm suggests that the Langmuir adsorption isotherm fits better than Freundlich isotherm for all the three adsorbents. This result suggests that the adsorption of chromium ion takes place onto homogeneous sites resulting in a monolayer.

The obtained parameters are summarized in supplementary Table S2. In MO, unlike the case of Cr(VI), the Freundlich isotherm model showed more agreement with the sorption equilibrium data (see Fig. S3c, d). Here the interaction between the adsorbent surface (ferrite nanoparticle) and the adsorbate (MO) can be explained in terms of two types of interactions. Firstly, the hydrogen bond formation between the ferrite surface and MO molecule: the elements present in MO such as nitrogen, oxygen and sulfur could form hydrogen bonds with the surface hydroxyl groups of ferrites. Secondly, MO is a polar molecule and hence it can prompt a dipole–dipole interaction between electropositive groups on the MO and the ferrite surface. The existence of those two, but different, types of adsorption sites is possibly the reason for the better fit of the Freundlich model—since the model assumes the heterogeneous surface for the adsorbent having adsorption sites with diverse energies of adsorption (Asuha et al. 2010).

Porosity analysis

As noted in Figs. 8 and 9 CFO has higher photocatalytic rate than CZFO and ZFO. To further study the adsorption mechanism leading to a higher photocatalytic activity for CFO, the analysis was done using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) and the Barrer–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) techniques. The techniques would help to understand adsorption mechanism in relation to the surface area and porosity. The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of the ferrite powders measured at − 195.80 °C are shown in Fig. 16a–c. The estimated surface area, pore diameter and pore volume of all samples are summarized in Table 2.

The inset demonstrates the BJH pore size distribution plot. In the ZFO and CZFO, the pore diameter ranges from 4 nm to 20 nm. Therefore, all pores in both the compounds are mesoporous. But in CFO, the pore diameter ranges from 2 to 190 nm. Thus in CFO, a substantial contribution to adsorption surface is offered by macropores (50–190 nm) also. The pores, in general, could perform as channels for the adsorption of chromium and methyl orange impurities. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of all the ferrites correspond to the IUPAC type-IV pattern representing the existence of mesoporous/macroporous structure in the prepared samples. The sorption isotherms of ZFO and CZFO samples exhibit typical H1 hysteresis (Peng et al. 2014) and the CFO sample demonstrates H3 hysteresis (Vignesh et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2014). The H1 type and H3 type suggest cylindrical pores and slit-like pores, respectively.

Based on the BET analysis, the surface area of the CFO nanoparticle is found to be larger than that of CZFO and ZFO, which suggests CFO to be a better adsorbent. The minimum crystallite size was obtained for CFO from the XRD analysis. Minimum crystallite size means a higher total surface area predicting an improved photocatalytic activity in CFO. In addition, the inset of Fig. 16c suggests a combination of meso and macro pores in CFO—similar that seen in another study (Liu et al. 2016). The presence of macrospores would improve the activity of the catalyst mainly in two ways: (i) it can enhance transfer of more incident photon flux onto the surface of the inner photoactive mesopores; (ii) the macrospores decrease intra-diffusion resistance for impurities and thus act as channels that can facilitate the increase in mass transport of reactants to more photocatalytic active sites (Li et al. 2015). Though CFO showed elevated surface area, its pore diameter was found to be less. It may be attributable to a large number of pores per gram present in the CFO sample (Palanisamy et al. 2013). In summary, (i) smaller crystallite size, (ii) higher surface area, (iii) combination of meso and macropores, (iv) higher density of pores and (v) reduction in band gap energy (due to reasons noted earlier), all together contributed to the enhanced catalytic activity for CFO in all the PC experiments, viz., Cr(VI) and MO contaminant degradation in their single- and binary-component systems.

The interaction between central metal atoms in the metal alkoxide, pH, ionic strength and synthesis conditions has a considerable role in determining microstructure formation of nanomaterials. The explanation behind the preferential formation of macropores in CFO, unlike ZFO and CZFO, would need a detailed study. It is reported that a speedy hydrolysis and condensation process is crucial for macropore formation (Hakim and Shanks 2009). The reaction mixtures of both zinc and cobalt ferrite nanoparticles have a slight difference in pH values (3.11 and 4.05 as measured in synthesis mixtures of ZFO and CFO, respectively). The difference in pH is due to the difference in solubility of inorganic species, its charge density, its rate of polymerization, etc. (Lemaire et al. 2011). Among various effects, the difference in pH also result in a fast precipitation of the metal oxide/hydroxide from solution—which may lead to the formation of macropores in CFO nanoparticles. In addition, the presence of surfactant molecules influences the hydrodynamic conditions, thereby determining the morphology and microstructure of metal oxides. Surfactants can increase the mesoporous nature by adsorbing the surfactant molecules on the surface of the nanoparticles to form a bilayer structure. This can improve the mesopore size distribution. Under optimum chemical environment, surfactants can also stimulate phase separation during the hydrolysis of metal alkoxides, in turn leading to the formation of macrospores.

Conclusions

Summarizing, the applicability of Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 ferrite nanospheres for the removal of chromium and methyl orange impurities from single- to mixed-polluted water system is reported in this study. The nanoparticles synthesized by the solvothermal method were found based on TEM to exist morphologically as nanospheres of diameter in the range 5–10 nm. The bifunctional nature of the ferrite nanoparticles to act as a photocatalyst for the simultaneous removal of the mixture of water contaminants and as superparamagnetic nanoparticles aiming at the magnetic separation process is demonstrated. In the Cr(VI)/MO binary system, under visible light irradiation, Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 exhibited a synergetic effect in photocatalytic MO degradation and hexavalent chromium reduction under visible light irradiation. The isotherm study indicated that the adsorption data for chromium and methyl orange onto Co x Zn1−xFe2O4 can be understood using Langmuir isotherm and Freundlich isotherms, respectively. Among the ferrites, CoFe2O4 sample maintained superior activity as a result of its smaller crystallite size, higher surface area and narrower band gap. Based on the BET analysis, it is demonstrated that the presence of the combination of the meso–macro pores in CoFe2O4 also contributed to the enhanced synergetic removal of hazardous contaminants in water. The mechanism responsible for synergetic photocatalysis is discussed. A detailed study of the intermediate products and the subsequent decay into harmless products would improve the real-world applicability of the discussed catalysts.

References

Abbas M, Rao BP, Kim C (2014) Shape and size-controlled synthesis of Ni–Zn ferrite nanoparticles by two different routes. Mater Chem Phys 147:443–451

Ali I (2012) New generation adsorbents for water treatment. Chem Rev 112:5073–5091

Ali IO, Mostafa AG (2015) Photocatalytic reduction of chromate oxyanions on MMnFe2O4 (M = Zn, Cd) nanoparticles. Mater Sci Semicond Process 33:189–198

Asuha S, Zhou XG, Zhao S (2010) Adsorption of methyl orange and Cr(VI) on mesoporous TiO2 prepared by hydrothermal method. J Hazard Mater 181:204–210

Barlow DA, Baird JK, Su C (2004) A Theory of the von Weimarn rules governing the average size of crystals precipitated from a supersaturated solution. J Cryst Growth 264:417–423

Cai C, Zhang Z, Liu J, Shan N, Zhang H, Dionysiou DD (2016) Visible light-assisted heterogeneous Fenton with ZnFe2O4 for the degradation of Orange II in water. Appl Catal B 182:456–468

Cao X, Guo X, Dong H, Meng J, Sun J (2014) Study on the synthesis and magnetic properties of rod-shaped NiFe2O4 ferrites via precipitation–topotactic reaction employing Na2C2O4 and NaOH as precipitants. Mater Res Bull 49:229–236

DavilaIbanez AB, Salgueirino V (2013) Chemical and kinetically controllable nucleation, aggregation-coalescence, and Ostwald ripening processes in the synthesis of magnetic CO–B nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C 117:4859–4865

Denton AR, Ashcroft NW (1991) Vegard’s law. Phys Rev A 43:3161–3164

Fan G, Tong J, Li F (2012) Visible-light-induced photocatalyst based on cobalt-doped zinc ferrite nanocrystals. Ind Eng Chem Res 519:13639–13647

Fresno F, Portela R, Suarez S, Coronado JM (2014) Photocatalytic materials: recent achievements and near future trends. J Mater Chem A 22:863–2884

Gurses A et al (2016) Dyes and Pigments, Springer briefs in green chemistry for sustainability. Springer, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33892-7_2

Hakim SH, Shanks BH (2009) A comparative study of macroporous metal oxides synthesized via a unified approach. Chem Mater 21:2027–2038

He HY (2012) Comparison study on magnetic property of Co0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 Powders by template-assisted sol–gel and hydrothermal methods. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 23:995–1000

Hou C, Yu H, Zhang Q, Li Y, Wang H (2010) Preparation and magnetic property analysis of monodisperse Co–Zn ferrite nanospheres. J Alloys Compd 491:431–435

Hu X, Ji H, Chang F, Luo Y (2014) Simultaneous photocatalytic Cr(VI) reduction and 2,4,6-TCP oxidation over g-C3N4 under visible light irradiation. Catal Today 224:34–40

Jacobs J, Testa SM (2004) Overview of chromium (VI) in the environment: background and history. E-Publishing, CRC Press, LLC, Boca Raton, pp 1–21

Jia Z, Peng K, Xu L (2012) Preparation, characterization and enhanced adsorption performance for Cr(VI) of mesoporous NiFe2O4 by twice pore-forming method. Mater Chem Phys 136:512–519

Kaur M, Kaur N, Jeet K, Kaur P (2015) MgFe2O4 nanoparticles loaded on activated charcoal for effective removal of Cr(VI)—a novel approach. Ceram Int 41:13739–13750

Lemaire A, Rooke JC, Chen L, Su B (2011) Direct observation of macrostructure formation of hierarchically structured meso-macroporous aluminosilicates with 3D interconnectivity by optical microscope. Langmuir 27:3030–3043

Li M, Li X, Jiang G, He G (2015) Hierarchically macro–mesoporous ZrO2–TiO2 composites with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Ceram Int 41:5749–5757

Liu H, Liu T, Zhang Z, Dong X, Liu Y, Zhu Z (2015a) Simultaneous conversion of organic dye and Cr(VI) by SnO2/rGO micro composites. J Mol Catal A Chem 410:41–48

Liu X, Zeng H, Xu S, Chen C, Zhang Z, Du J (2015b) Metal oxides as dual functional adsorbents/catalysts for Cu2+/Cr(VI) adsorption and methyl orange oxidation catalysis. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 000:1–9

Liu Y, Lan K, Bagabas AA, Zhang P, Gao W, Wang J, Sun Z, Fan J, Elzatahry AA, Zhao D (2016) Ordered macro/mesoporous TiO2 hollow microspheres with highly crystalline thin shells for high-efficiency photo conversion. Small 12:860–867

Makovec D, Sajko M, Selisnik A, Drofenik M (2012) Low-temperature synthesis of magnetically recoverable, superparamagnetic, photocatalytic, nanocomposite particles. Mater Chem Phys 136:230–240

Manikandan A, Vijaya JJ, Kennedy LJ, Bououdina M (2013a) Structural, optical and magnetic properties of Zn1−xCu x Fe2O4 nanoparticles prepared by microwave combustion method. J Mol Struct 1035:332–340

Manikandan A, Vijaya JJ, Sundararajan M, Meganathan C, Kennedy LJ, Bououdina M (2013b) Optical and magnetic properties of Mg-doped ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles prepared by rapid microwave combustion method. Superlattices Microstruct 64:118–131

Manikandan A, Kennedy LJ, Bououdina M, Vijaya JJ (2014) Synthesis, optical and magnetic properties of pure and Co-doped ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles by microwave combustion method. J Magn Magn Mater 349:249–258

Mou F, Guan J, Sun Z, Fan X, Tong G (2010) In situ generated dense shell-engaged Ostwald ripening: a facile controlled-preparation for BaFe12O19 hierarchical hollow fiber arrays. J Solid State Chem 183:736–743

Nanakkal AR, Alexander LK (2017) Graphene/BiVO4/TiO2 nanocomposite: tuning band gap energies for superior photocatalytic activity under visible light. J Mater Sci 52:7997–8006

Palanisamy B, Babu CM, Sundaravel B, Anandan S, Murugesan V (2013) Sol–gel synthesis of mesoporous mixed Fe2O3/TiO2 photocatalyst: application for degradation of 4-chlorophenol. J Hazard Mater 252–253:233–242

Peng X, Huang D, Odoom-Wubah T, Fu D, Huang J, Qin Q (2014) Adsorption of anionic and cationic dyes on ferromagnetic ordered mesoporous carbon from aqueous solution: equilibrium, thermodynamic and kinetics. J Colloid Interface Sci 430:272–282

Qu X, Alvarez PJJ, Li Q (2013) Applications of nanotechnology in water and Waste water treatment. Water Res 47:3931–3946

Reddy DHK, Yun Y (2016) Spinel ferrite magnetic adsorbents: alternative future materials for water purification? Coord Chem Rev 315:90–111

Reddy MP, Mohamed AMA, Zhou XB, Du S, Huang Q (2015) Facile hydrothermal synthesis, characterization and magnetic properties of mesoporous CoFe2O4 nanospheres. J Magn Magn Mater 388:40–44

Singh C, Jauhar S, Kumar V, Singh J, Singhal S (2015) Synthesis of zinc substituted cobalt ferrites via reverse micelle technique involving in situ template formation: a study on their structural, magnetic, optical and catalytic properties. Mater Chem Phys 156:188–197

Tang SCN, Lo IMC (2013) Magnetic nanoparticles: essential factors for sustainable environmental applications. Water Res 47:2613–2632

Vignesh K, Priyanka R, Rajarajan M, Suganthi A (2013) Photoreduction of Cr(VI) in water using Bi2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposite under visible light irradiation. Mater Sci Eng B 178:149–157

Wang J, Ren F, Jia B, Liu X (2010) Solvothermal synthesis and characterization of NiFe2O4 nanospheres with adjustable sizes. Solid State Commun 150:1141–1144

Wang L, Li J, Wang L, Zhao L, Jiang Q (2012) Adsorption capability for Congo red on nanocrystalline MFe2O4 (M = Mn, Fe Co, Ni) spinel ferrites. Chem Eng J 181–182:72–79

Wang Y, Zhao H, Li M, Fan J, Zhao G (2014) Magnetic ordered mesoporous copper ferrite as a heterogeneous Fenton catalyst for the degradation of imidacloprid. Appl Catal B 147:534–545

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Kerala State Council for Science, Technology & Environment-SRS Project 107/2016. Bintu Thomas acknowledges the fellowship assistance received from UGC BSR-SAP. The authors acknowledge Dr. P.A. Joy, Senior Principal Scientist, CSIR-NCL Pune, for conducting VSM measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, B., Alexander, L.K. Enhanced synergetic effect of Cr(VI) ion removal and anionic dye degradation with superparamagnetic cobalt ferrite meso–macroporous nanospheres. Appl Nanosci 8, 125–135 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-018-0655-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-018-0655-6