Abstract

The purpose of this research is to propose a comprehensive conceptualization of the market orientation construct that acknowledges the role of salient stakeholders in value co-creation. The proposed multiple stakeholder market orientation (MSMO) construct is a more broadly defined conceptualization of what it means to implement the marketing concept in a multi-stakeholder business environment. The construct is developed within the context of prevailing theoretical perspectives including the service-dominant logic of marketing, stakeholder theory, and the market orientation paradigm. Specifically, the construct is developed as an interconnected operant resource consisting of a stakeholder orientation, a systems orientation, and a shared value orientation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Nearly three decades have passed since the respective works of Narver and Slater (1990) and Kohli and Jaworski (1990) first specified an operational approach to the marketing concept in the form of the market orientation (MO) construct. Positioning customers and competitors as the principal stakeholders of strategic marketing decisions, the MO paradigm suggests that an organizational culture committed to generating and reacting to information from the product market provides firms with the basis for achieving a sustained competitive advantage, and in turn, increased firm performance. Market orientation is conceptualized as the extent to which a firm capitalizes on this process (Kohli and Jaworski 1990; Narver and Slater 1990) and is recognized as a core concept in marketing strategy and a critical determinant of firm performance (Kirca et al. 2005).

However, the existing conceptualization of the market orientation construct is not sufficient to explore business model innovations such as the sharing economy, digital media, and global supply chain configurations that are changing the basis of competition in the contemporary marketing environment (Hult and Ketchen 2017; Robertson 2017; Sett 2017). While proactive and market-driving approaches to address market disruptions are often advocated (Jaworski et al. 2000; Narver et al. 2004), the dominant empirical approach defines a market orientation as an intra-firm strategic position, largely ignoring actors outside of the traditional marketplace. As such, MO is often criticized as too narrow in focus (e.g., Ferrell et al. 2010; Greenley et al. 2005; Matsuno et al. 2000). Critics contend that, although customer- and competitor-level information are important components of strategic marketing decisions, a number of equally important stakeholder markets (e.g., suppliers, community groups, governments, etc.) should be considered in decisions related to the implementation of the marketing concept (Carpenter 2017; Hult 2011a; Maignan and Ferrell 2004).

The increasing calls for marketing scholars to consider multiple stakeholders in the broader context of social and environmental issues has prompted debate on the nature of marketing, marketing theory, and the market orientation construct (Hult 2011a; Hult and Ketchen 2017). For example, the American Marketing Association (AMA) introduced the word “stakeholders” to its definition of marketing in the 2004 revision, and then subsequently replaced the word with “society at large” 3 years later (Gundlach and Wilkie 2010). The ambiguous nature of the stakeholder in the definition of marketing suggests that the role of non-market actors (i.e., stakeholders) in the marketing function is still an unresolved issue.

One theoretical response to this issue lies in the service-dominant logic (S-D logic) of marketing, a perspective through which Vargo and Lusch (2004) argue that value is co-created by parties internal and external to all firms. Extending this perspective, Lusch and Vargo (2006) suggest that scholars should more closely consider the role of marketing in shaping legal, social, and environmental concerns. In response to such calls, Hult (2011b) identified the boundary-spanning marketing organization as “an entity encompassing marketing activities that cross a firm’s internal and external customer value-creating business processes and networks for the purposes of satisfying the needs and wants of important stakeholders” (p. 509). Similarly, Porter and Kramer (2011) highlight the importance of strategically addressing the social issues directly impacting marketing performance by redefining business in terms of the value it shares with communities.

In alignment with the S-D logic, proponents of what has been called the stakeholder marketing movement (Bhattacharya and Korschun 2008) suggest that the customer-centric approach characterizing the current MO paradigm marginalizes the increasingly important role of salient non-market stakeholders within the context of value creation. Stakeholder marketing refers to “activities within a system of social institutions and processes for facilitating and maintaining value through exchange relationships with multiple stakeholders” (Hult et al. 2011, p. 57). Within the general business literature, a stakeholder orientation towards groups such as shareholders, investors, employees, and community groups emphasizes the creation of firm value (Greenley and Foxall 1997; Maignan and Ferrell 2004). The S-D logic broadens the stakeholder approach, seeking to explore value creation within the multiple stakeholder domains that form a marketing system (Ekman et al. 2016; Frow and Payne 2011).

In the spirit of stakeholder marketing and S-D logic, the purpose of this research is to propose a more broadly defined and comprehensive conceptualization of a market orientation that acknowledges the role of salient stakeholders in value co-creation, a strategic orientation referred to herein as a multiple stakeholder market orientation (MSMO). As follows, we define MSMO as a set of organizational behaviors reflective of an organization-wide commitment to total value creation by (1) understanding and reacting to the needs of salient stakeholder markets and (2) generating and communicating information across these markets. Conceptualized within the context of stakeholder theory and shared value, MSMO is positioned as a more appropriate framing of the MO paradigm in terms of Kotler’s (1972) generic concept of marketing as well as Vargo and Lusch’s (2004) S-D logic of marketing. Table 1 compares the proposed MSMO to extant conceptualizations of a market orientation (Kohli and Jaworski 1990; Narver and Slater 1990), stakeholder orientation (Maignan and Ferrell 2004; Yau et al. 2007), and multiple stakeholder orientation profile (Greenley and Foxall 1997). As seen in the table, MSMO is positioned as a more broadly defined conceptualization of what it means to implement the stakeholder-marketing concept in the contemporary business environment.

The primary contribution of MSMO lies in its comprehensive approach to creating value for stakeholders. Differing from other conceptualizations of market orientation and stakeholder orientation, MSMO considers the value generated by all stakeholders. That is, by acknowledging the tenets of stakeholder marketing and the corresponding perspective of marketing as an activity enacted within a complex network of inter-organizational relationships, MSMO mandates that managers consider value creation from a systems perspective (cf Lusch and Webster Jr 2011), resulting in total value creation (i.e., for the firm, customers and salient stakeholders). In the following sections, we discuss the underlying theoretical frameworks of MSMO. Through the lenses of MO, S-D logic and stakeholder theory, we then integrate Madhavaram and Hunt’s (2008) resource advantage theory (RA) to explicate multiple stakeholder market orientation as a higher order strategic perspective, positing a comprehensive shared-value approach to total value creation. Additionally, we propose outcomes that firms’ may expect from adopting a MSMO, suggest measurement considerations for the construct, and discuss the implications of our research.

Theoretical framework

Kotler’s (1972) generic concept of marketing stipulates that the principles of marketing need not be confined to traditional conceptualizations of “products” and “customers” and that marketing science can (and should) be applied to all “publics” (p. 46, 48) with which an organization engages. Thus, the generic concept of marketing argues that transactions or exchange (Bagozzi 1975) need not necessarily take place between an organization (or individual) and a consuming public in order for the tenets of marketing to apply. Although such transactions are certainly included within marketing’s scope (Hunt 1976), the generic concept of marketing advocates the application of marketing principles within the context of all relevant publics.

In accordance with this generic conceptualization of marketing, the AMA currently defines marketing as “the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large” (AMA 2017). The AMA’s definition however, is anything but stable. Over the last 40 years, the official definition of marketing has been revised a number of times to reflect periodic shifts in the nature and scope of marketing thought. During its progression, the dominant view of marketing has evolved from a “business only” phenomenon to its current conceptualization as an interactive, value-creating process (Vargo and Lusch 2004) relevant to any organizational (or personal) exchange. Correspondingly, the conceptualization of exchange has shifted from a dyad-based value exchange perspective to a complex exchange of value within (and among) networks (Hillebrand et al. 2015).

However despite the significant and fundamental changes to the nature and scope of marketing thought over the years, the general paradigm used to operationalize the marketing concept itself (i.e., market orientation as a reflection of customer and competitor engagement) has remained largely static. This perspective reflects neither the generic concept of marketing nor the increasing importance of stakeholder theory to the field of marketing science. Thus, although the operational definition of a market orientation came nearly 20 years after Kotler’s (1972) call for an expansion of the scope of marketing to include non-financial exchanges between an organization and its publics, market-level transaction/exchange remains the central tenet of the marketing concept (at least at an operational level), implying that a market orientation is achieved only within the strategic context of product-market actors (i.e., customers and competitors).

In light of this shortcoming, the purpose of this paper is to align the tenets of marketing to the context of transactions with (and among) stakeholders, for the purposes of total value creation. Specifically, we suggest that while a customer focus is undoubtedly central to the marketing concept, the creation of value should expand beyond a customer-centric focus. Further, we suggest that an organization has the potential to create value through all of its transactions, regardless of the transacting partner (cf Lusch and Webster Jr 2011), and that the extent to which the marketing concept is applied to these transactions should accordingly be reflected in the operationalization of the organization’s strategic orientation. This system-based view of the marketing organization focuses attention on the full range of actors that create value for firm stakeholders (cf El-Ansary et al. 2018).

Advancing the systems view of marketing, Hult (2011b) describes a boundary-spanning marketing organization in terms of stakeholder relationships, network resources, and value creation. Notably, our framework is based on several organizational theories of the firm including stakeholder theory, the S-D logic of marketing, and the market orientation paradigm. A review of this literature highlights a convergence of these theoretical perspectives to broaden the stakeholder and value concepts in the marketing domain. Table 2 provides a summary of salient literature that highlights the overlap and disparities of the underlying theories.

Market orientation

The premise of the contemporary conceptualization of a market orientation began with positioning customers as the principal driver of firm performance. In various ways, the construct was broadly defined in terms of specific organizational behaviors (Kohli and Jaworski 1990), organizational cultures (Narver and Slater 1990), and organizational skills (Day 1994a) enacted vis-à-vis the consumer marketplace. Surprisingly, however, Carpenter (2017) notes that most research on MO has focused on the firm itself without considering the value accrued by the customer. As evidence, the articles reviewed in Table 2 predominantly adopt a dyadic view of the customer/firm relationship and measure firm-centric value. Thus, while a proactive MO considers “opportunities for customer value of which the customer is unaware” (Narver et al. 2004, p. 334), empirical research has largely focused on firm competitiveness.

More recently, MO research has started to examine firm approaches to integrating customer and market considerations in marketing strategy. For example, Narver et al. (2004) differentiate a responsive (customer-led) orientation from a proactive (customer leading) orientation, the latter of which focuses on identifying latent needs to create new products that increase customer value. Similarly, Jaworski et al. (2000) differentiate a reactive market-driven strategy from a market-driving strategy that examines the roles of all actors in a value chain to shape the market through eliminating or changing the value function. Recently, Jaworski and Kohli (2017) encouraged increased academic attention to these market-driving strategies, stating “the idea of shaping, molding, and managing the evolution of markets has been around for some time, but has not taken off in terms of systematic inquiry” (p. 11).

Recent developments in the marketing environment suggest that the time is right for such inquiry. For example, the sharing economy changes the way customers acquire goods or services and creates a new marketing channel that restructures the value chain (Gonzalez-Padron 2017). Accordingly, Robertson (2017) proposes a market-driving approach to MO in the context of these disruptive business models. Such an approach entails restructuring the value chain by eliminating an intermediary, creating a new market structure, changing the roles of the players in the value chain, or even requiring different capabilities and resources (Jaworski et al. 2000; Sett 2017).

These market disruptions (and subsequent shifts from a customer-centric view of marketing) necessitate rethinking the concepts of value and stakeholders, especially as they relate to the adoption of a market orientation. For example, Sett (2017) suggests that firms in a rapidly changing market should emphasize value creation and value recapture, stressing that changes in market structure may negatively affect firm value. Based on the belief that value is created when a firm considers stakeholders beyond customers, Sett goes on to suggest the importance of the ability to sense the market to gather intelligence on all stakeholders or entities that may affect the firm. Similarly, in advocating for value delivery to include the company’s primary stakeholders, Hult (2011a) calls for a “market orientation plus” or “market-focused sustainability” orientation that considers social, economic, and environmental issues in marketing strategy.

Unfortunately, while attending to value creation in a broader stakeholder network is a well-founded concept, measuring this type of stakeholder value remains a difficult task. As follows, we suggest that a stakeholder-marketing approach can address several of the issues raised above. Specifically, it addresses (1) emerging business models that change traditional value-creation and exchange relationships for customers, sellers, and the community and (2) the business impact of these models on society-at-large.

Stakeholder theory and stakeholder marketing

In contrast to traditional input-output models of the firm, stakeholder theory argues that managers should be concerned not only with competitors and customers, but with all actors who possess a legitimate interest in the firm’s activities (Donaldson and Preston 1995; Freeman 1984). Although customers and competitors fit the conceptualization of a stakeholder defined as such, stakeholder theory suggests the existence of numerous other stakeholders in a firm’s activities. Within the general business literature, groups such as shareholders, customers, employees, suppliers/distributors, regulators, and the host community (Ferrell et al. 2010; Greenley and Foxall 1997) are all identified as fitting the more broadly defined concept of the stakeholder.

The stakeholder concept represents a redefinition of organizations as a grouping of stakeholders. Accordingly, the purpose of the organization is to manage the interests of all groups (Friedman and Miles 2006) implying that companies addressing diverse stakeholder interests perform better than companies that do not. Stakeholder theory argues that managers must satisfy various constituents that would withdraw support for the firm if important social responsibilities were unmet (Freeman 1984). According to Clarkson (1995), the survival and profitability of the corporation depends on its ability to create and distribute wealth or value to ensure primary stakeholder commitment.

Stakeholder theory incorporates the organization’s cultural orientation towards multiple stakeholders through a stakeholder orientation (Maignan et al. 2005). Stakeholder orientation refers to the extent to which a firm understands and addresses stakeholder demands in daily operations and strategic planning. Adoption of a stakeholder orientation provides firms an opportunity to understand the impact of its activities on stakeholders, anticipate changing societal expectations, and use its capacity for innovation to create additional business value from superior social and environmental performance (Laszlo et al. 2005).

While stakeholder orientation has been conceptualized in a number of ways (e.g., Greenley et al. 2005; Maignan and Ferrell 2004; Yau et al. 2007), the existing approaches share two important characteristics. First, they are all based on the firm’s efforts to identify, assess and consider relevant stakeholder issues in strategic decision-making. Additionally, the dominant focus is on a dyadic relationship between the firm and its stakeholders, with firm value being derived from resources granted or withheld by stakeholders. Together, these two aspects of a stakeholder orientation propagate a firm-centric view of marketing.

Moving beyond this firm-centric, dyadic perspective, the idea of stakeholder marketing advocates a network-oriented approach to stakeholder management (Bhattacharya and Korschun 2008). Proponents of stakeholder marketing encourage firms to adopt a societal perspective to create stakeholder benefits (Hillebrand et al. 2015; Laczniak and Murphy 2012) that deliver economic and social value to employees, suppliers and the community (Gonzalez-Padron et al. 2016). Case studies and firm surveys have found evidence of a competitive advantage that accrues to firms that can create this type of shared value for stakeholders (Maignan et al. 2011; Mish and Scammon 2010). When firms successfully create value for all the stakeholders in a marketing system, the resulting network of relationships are difficult for competitors to imitate (Kull et al. 2016).

Notably, there is growing convergence between the tenets of stakeholder marketing that emphasize networked value creation and the idea of value co-creation espoused by S-D logic. For example, Hillebrand et al. (2015) suggest that “building networks for shared value creation that give stakeholders a sense of identification with the firm (and the rest of the network)” (p. 420) results in stakeholder willingness to provide valuable resources to the firm. Likewise, Tantalo and Priem (2016) recommend a stakeholder synergy perspective where a firm seeks strategic actions that create value for two or more stakeholder groups without reducing value received by any other stakeholder group. In a similar manner, Lusch and Webster Jr (2011) acknowledge the role of stakeholders in the co-creation of value within the context of S-D logic. As follows, we discuss the potential for further integration of stakeholder theory and the marketing concept under the auspices of the S-D logic.

The service-dominant logic

While the purpose of the organization under the stakeholder concept is to manage stakeholders, the S-D logic suggests that the purpose of a marketing organization is to serve customers and stakeholders with a goal of total value creation for all stakeholders (Vargo and Lusch 2004, 2008). The S-D logic views marketing as value creation that takes place within and between systems, focusing on resource integration to create value. In the S-D logic framework, however, value is achieved via the exchange of a firm’s operant resources (e.g., knowledge and skills), not the exchange of tangible goods. This position is central to the S-D logic concept, where Vargo and Lusch (2004, p. 2) define a service as “the application of specialized competences (knowledge and skills) through deeds, processes, and performances for the benefit of another entity or the entity itself.”

Embedded within the S-D logic is the view that no single economic entity may unilaterally dictate the notion of value. Thus, value is co-created through the interaction of the firm with customers, competitors and other salient stakeholders (Lusch and Webster Jr 2011; Vargo and Lusch 2004). More pointedly, Lusch and Webster Jr (2011) argue that maximizing customer value is less important than maximizing collective value across all salient stakeholders. Importantly, this does not mean that S-D logic views customers as unimportant. Rather, this statement distinguishes end-user customers from other types of customers, emphasizing the idea that all transacting partners are social actors, engaged in the exchange process.

Recently, this idea has evolved to an actor-to-actor (A2A) conceptualization of the market (Vargo and Lusch 2011). Rather than (1) characterizing markets based on arbitrary distinctions between producer and consumer and (2) distinguishing transactions based on this dichotomy (e.g., B2B, B2C, etc.), the A2A approach “points toward a dynamic, networked and systems orientation to value creation” (Vargo and Lusch 2011, p. 181). The term “system” here refers to the totality of parties engaged in economic exchange working toward a common goal of value creation. This concept of a systems orientation is critical, as it can be directly contrasted with a market orientation. Unlike a pure MO, which sees value as arising in the form of a value proposition, a systems orientation sees value as a co-creational phenomenon, achieved only within the context of networks composed of a firm, its customers and any other stakeholder laying claim to network membership (Lusch and Webster Jr 2011).

Adopting a S-D logic leads to a broader definition of value creation as total value accrued to all firm stakeholders. Creating stakeholder value requires balancing the value propositions of all social and economic actors of a marketing system to gain a competitive advantage (Frow and Payne 2011). In such a system, value is determined by the beneficiary and may include economic value through cost saving and revenue generation, or intangible benefits such as brand building, reputation, environmental protection, and societal welfare (Ekman et al. 2016; Vargo and Lusch 2016). The total value created by a firm’s service offering is distributed among multiple stakeholders in a number of different ways, such as wages to employees, dividends to shareholders, payments to suppliers, taxes to governments, customer benefit, firm profit, and potentially to other firms through imitation (Garcia-Castro and Aguilera 2015; Mizik and Jacobson 2003). Therefore, measuring value for all stakeholders must consider (1) a multifaceted conceptualization of value, (2) the disparate values of some stakeholder groups, and (3) stakeholder network complexities.

If the previous statements are true, then the customer- and competitor-centric conceptualizations of MO are not in alignment with the contemporary notion of value creation. That is, while information generation, dissemination, and reaction are still key to maximizing value for customers and stakeholders, no longer can this information come only from “the market” nor can it be used simply for the creation of (narrowly speaking) customer value. Instead, information must be generated and disseminated across stakeholders for the purpose of value creation in toto. Lusch and Vargo (2011) suggest as much in their statement that “social and economic actors are embedded in a soup of potential resources and are always integrating resources to create new resources” (p. 195). Adopting a multiple stakeholder market orientation is about identifying the ingredients in that soup.

Multiple stakeholder market orientation

The integration of the marketing concept with stakeholder theory and S-D logic allows for a more dynamic conceptualization of the MO construct and the emergence of a higher-order strategic perspective as implied in RA theory (Madhavaram and Hunt 2008), a phenomenon to which we refer as a multiple stakeholder market orientation (MSMO). We suggest that MSMO reflects a more accurate conceptualization of the marketing concept within the current paradigm of marketing thought than does the relatively less inclusive MO. Thus, as follows, MSMO is positioned as a more appropriate reflection of both the generic concept of marketing (Kotler 1972) and the S-D logic (Vargo and Lusch 2004).

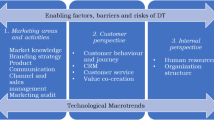

Figure 1 provides an illustration of the comprehensive approach to this construct as a higher-order bundle of resources that can be used to create value for the firm and society. We use the term “higher-order” here to differentiate between MO and MSMO based on (1) resource bundling and (2) how such resources are leveraged for competitive advantage. Based on Ngo and O’Cass’ (2009) suggestion that operant-based capabilities (such as MO, or other appropriate strategic postures) help explain differential value offerings, we argue that because MSMO employs a broader set of operant capabilities than does MO, the former can be seen as a higher order resource, or what Madhavaram and Hunt (2008) refer to as an interconnected operant resource. Accordingly, in accordance with the tenets of RA theory, we propose that organizations that adopt the more comprehensive MSMO may gain sustainable competitive advantage vis-à-vis competitors. Further, we propose that such gains come not just from the interconnection of resources but from a more inclusive approach to stakeholder prioritization as espoused by the systems approach to stakeholder value creation advocated by the S-D logic and RA theory.

An interconnected operant resource

In consideration of the theoretical arguments concerning the need for a more inclusive conceptualization of a market orientation, we now begin a more focused discussion of the MSMO construct. As proposed, MSMO includes a set of organizational behaviors reflective of an organization-wide commitment to total value creation by understanding and reacting to the needs of salient stakeholder markets, while generating and communicating relevant information across these markets. This definition and conceptualization aligns with the meaning of a strategic orientation outlined by Varadarajan (2017) by including firm behaviors that lead to value creation throughout the marketing system. As depicted in Fig. 1, MSMO bundles operant resources to create value for the firm and its stakeholders.

In order to confer a sustainable competitive advantage, resources must be rare, inimitable, valuable and non-substitutable (Barney 1991). A further conceptualization of sustainable advantage is the ability of firms to combine resources into higher-order resource bundles (Madhavaram and Hunt 2008). These authors refer to a single resource as a basic operant resource (BOR). Alone, a BOR represents a relatively weak source of sustainable competitive advantage. However, when organizations combine BORs into bundles of interrelated resources, Madhavaram and Hunt (2008) refer to the result as a composite operant resource (COR). These resource bundles are both difficult to acquire (e.g., from a competitor), take longer to develop, are not easily imitated and, if leveraged properly, are more likely to represent a source of sustained competitive advantage.

As Madhavaram and Hunt (2008) point out, market orientation is itself a COR. A market orientation combines three BORs (information generation, intelligence dissemination and the ability to respond tactically vis-à-vis customers and competitors) into a bundled resource. Likewise, stakeholder orientation is a COR, as stakeholder orientation incorporates similar BORs as those that make up a market orientation. An MSMO does this as well but within the context of a more broadly defined stakeholder network, creating a higher-order resource (relative to a more simply defined market orientation). Thus, MSMO moves beyond the intra-firm (and thus limiting) focus of MO to engage in inter-firm generation of information, dissemination of intelligence and response to each, across and between all salient stakeholders to create value for all actors in the marketing system. In sum, MSMO combines a complex set of composite operant resources (stakeholder orientation, a systems perspective/A2A conceptualization of the marketplace, and shared value orientation) to create what Madhavaram and Hunt (2008) refer to as an interconnected operant resource (IOR). Each is discussed as follows.

Stakeholder orientation

As discussed previously, stakeholder orientation refers to the extent to which a firm understands and addresses stakeholder demands to create firm value. A stakeholder orientation assesses the firm’s attitude toward stakeholders and the level of activities relating to information generation, internal dissemination of knowledge to employees, and the response to relevant stakeholder issues in strategic decision-making (Maignan and Ferrell 2004; Yau et al. 2007). Accordingly, we propose that a MSMO mandates that organizations (1) generate, interpret, and react to information pertaining to the stakeholders’ interests in, and expectations of, the organization; and (2) communicate the results of these analyses to other relevant stakeholders.

Stakeholder prioritization

A distinguishing component of MSMO from MO is that there are no a priori assumptions regarding the stakeholder markets towards which an organization should be oriented. Additionally, the definition of MSMO refers to the prioritization of salient stakeholder markets. Because different firms will have different salient stakeholder markets depending on location, industry, legal status, etc. (Donaldson and Preston 1995), it is critical to provide an appropriate explication of what it means to be a salient organizational stakeholder. Ferrell et al. (2010) suggest that an actor is a stakeholder of an organization when at least one of the following conditions is met:

(1) the actor can potentially be affected (either positively or negatively) by the organization’s activities and/or the actor has an interest in the organization’s potential to affect its own or others’ well-being, (2) when the actor has the power to give or take away resources necessary for the continuation of the organization’s activities, and/or (3) the overall culture within the organization values the activities of the actor (p. 94)

At a minimum, a salient stakeholder must meet one of these three criteria. However, because Ferrell et al.’s (2010) definition, if interpreted loosely, could potentially include every person and organized group in existence as a salient organizational stakeholder, the onus is on the manager (or scholar) to determine which stakeholders should be attended to in any organization- or industry-specific operationalization of MSMO. Thus, close attention to earlier literature as well as the interpretation of practical managerial data are essential to an exposition of a given organization’s MSMO.

The degree of legitimacy and power that a stakeholder group exhibits towards the firm should determine which stakeholders require attention (Donaldson and Preston 1995; Ferrell et al. 2010; Mitchell et al. 1997). In this way, the stakeholder prioritization process inherent to a multiple stakeholder market-oriented organization can be described in the language of Donaldson and Preston (1995) as both normative and managerial. Donaldson and Preston (p. 67) suggest that “stakeholder management requires, as its key attribute, simultaneous attention to the legitimate interests of all appropriate stakeholders, both in establishment of organizational structures and general policies and in case-by-case decision making.” Likewise, we suggest that those firms that excel in distinguishing salient stakeholders from those that are less important may develop a competitive advantage compared to a more myopic competitor.

Stakeholder information generation and dissemination

Organizations adopting an MSMO leverage stakeholder information generation and dissemination with the recognition that the marketing function has moved beyond a mere customer/competitor focus. Thus, instead of generating and disseminating information from consumer markets only, firms adopting a MSMO pursue information across the spectrum of stakeholder markets. Likewise, instead of taking a myopic, inward focus concerning the dissemination of that information, those firms promote information externally as well. From a knowledge generation/dissemination standpoint, this means that firms must generate information about the system (as opposed to the market only) and then disseminate it through the entire system (as opposed to internal dissemination only).

For example, Walmart gathers large amounts of data on its own energy use (at the store level, distribution centers, contract factories, etc.) in an effort to enhance ROI dollars from greater efficiencies (Johnston 2013). From a classic MO perspective, these data would be for internal consumption only, designed to determine the cost-saving measures’ effects on customer value. From an MSMO perspective however, saving energy conveys an image of corporate social responsibility, thus burnishing Walmart’s public image. Therefore, data on how Walmart has reduced its carbon footprint through more efficient in-store lighting should be disseminated to interested NGOs (e.g., Sierra Club), suppliers (e.g., CPG companies whose packages may be affected by new lighting fixtures), the media (to generate positive PR) and finally to governments at all levels (e.g., to confirm that tax abatements were worthwhile).

Systems orientation

The idea of passing knowledge and information through a collaborative network is central to the MSMO framework. Under the new dominant logic of marketing, it is no longer sufficient to simply generate knowledge from the marketplace and then disseminate it internally (cf Kohli and Jaworski 1990). Accordingly, a systems orientation is central to an S-D logic. It is also similar to the idea of network competence, a COR that enables a firm to establish and use relationships with other firms (Madhavaram and Hunt 2008). We propose two firm-level constructs that lead to a systems orientation – market sensing and resource integration.

Market sensing

Market sensing is a well-established aspect of market driven firms. Day (1994a) introduced the process of market sensing, described as acting on information through “open-minded inquiry, synergistic information distribution, mutually informed interpretations, and accessible memories” (p. 44). Importantly, Day’s sensing process stipulates that generating and disseminating information is not enough to anticipate market changes. Morgan (2012) recognizes this in the description of market sensing as a broader market-learning ability “to actively and purposefully learn about customers, competitors, channel members, and the broader business environment in ways that not only allow a deep understanding of the current marketplace conditions but also permit future marketplace changes to be predicted” (p. 109).

Market sensing can help enhance innovation and create societal value through relationships in stakeholder networks. Marketers able to sense and respond to new knowledge among partners in the marketing system are better equipped to survive technological and global threats to their businesses (Velu 2015). Accordingly, Dentoni et al. (2016) argue that a stakeholder orientation for cross-sector partnerships of private sector, governments, and NGOs should include (among other things), sensing stakeholders as a key aspect of stakeholder management. They describe sensing stakeholders as:

The ability of identifying both existing and potential stakeholders and understanding their needs and demands; recognizing conflicting views among multiple stakeholders, their dynamics and the changing nature of their requests; assessing stakeholders’ (tangible and intangible) resources and capabilities; finding and processing information about their stakeholders to evaluate new opportunities for collaboration (p. 40).

As an example, Dentoni and colleagues cite Heinz’ move from simply demanding a responsible supply chain to its efforts in partnering with NGO’s like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil and the Rainforest Alliance to provide direct value to the company through certification of farmers.

Sett (2017) also advocates for a system-centric approach to MO that requires market sensing to gather intelligence on all stakeholders or entities that assist or prohibit the firm’s response to disruptive innovation. Accordingly, we propose that market sensing should no longer be limited to the consumer marketplace (i.e., customers and competitors). An expanded view of market sensing incorporates all stakeholders, supports a systems orientation, and along with the process of resource integration, is central to the idea of an MSMO.

Resource integration

Value creation under the S-D logic relies on resource integration by all actors in a marketing system. A fundamental premise of the S-D logic is that “all social and economic actors are resource integrators” which “implies the context of value creation is networks of networks” (Vargo and Lusch 2008, p. 7). A decade after the introduction of S-D logic, Vargo and Lusch (2017) observe that, in a systems orientation, the “key to value co-creation was the ongoing interplay of resource creation and application afforded through reciprocal exchange and differential access and integration” (p. 48).

Marketing generally defines resource integration as a process whereby actors interact with and use resources. Therefore, it is only through the deployment of resources that value is realized by the beneficiaries of the marketing system (Edvardsson et al. 2014; Laud et al. 2015). Thus, a capacity for resource integration includes the ability for system actors to access, mobilize, and deploy resources. Describing resource integration as a reconfiguration of network resources, Sett (2017) defines the reconfiguration of resources in terms of “the firm’s capacity to maintain competitiveness through enhancing, combining, protecting, and when necessary, reconfiguring tangible as well as intangible resource bases” (p. 7). Similar to the resource integration practices of Laud et al. (2015), reconfiguration of resources requires the ability to access, bundle and deploy internal, alliance and market resources (Sett 2017). Thus, bundling is about creating value by adapting and combining complementary resources.

Shared value orientation

The primary contribution of MSMO lies in its comprehensive approach to creating value for stakeholders. Instead of viewing value creation as a zero-sum game where the firm protects its share of economic value (Mizik and Jacobson 2003), a shared value orientation considers the economic and social value accrued to all the stakeholders of the firm (Garcia-Castro and Aguilera 2015). As Porter and Kramer (2011) suggest, such a view is about “expanding the pool of economic social value” (p. 65) rather than a redistribution of value.

As an example, Nestlé S.A. embraces a shared value perspective in marketing food by “offering tastier and healthier choices” and “inspiring people to lead healthier lives” (Nestlé 2017, p. 10). To ensure food safety, Nestlé works with farmers that provide the raw materials used to make their products. For example, milk is an ingredient in a wide range of Nestlé’s products including infant nutrition, ice cream, chocolates, and beverages. According to the 2016 Creating Shared Value report, Nestlé purchases milk from 353,000 farmers in 30 countries, who receive onsite support to monitor quality and safety; technical and veterinary support; financial assistance, and a consistent revenue stream. Thus, Nestlé acquires a secure supply for its products, while farmers increase yields and income. The key to Nestlé’s shared value orientation is engagement with stakeholders to align their goals with firm value creation (Porter and Kramer 2011).

Following stakeholder marketing’s societal perspective on the creation of stakeholder benefits (Hillebrand et al. 2015; Laczniak and Murphy 2012) and the S-D logic’s premise that marketing should strive to create value for all stakeholders (Vargo and Lusch 2004, 2008), MSMO mandates that managers consider value creation from a systems perspective through a shared value orientation. Some criticize the shared value concept as lacking in terms of organizational guidance regarding implementation (Dembek et al. 2016). We elaborate on the concept by proposing two key aspects of a shared value orientation: stakeholder value driver alignment and stakeholder value proposition.

Stakeholder value driver alignment

Studies show that stakeholder groups interpret value differently, including economic and non-economic drivers (Ekman et al. 2016; Garriga 2014; Tantalo and Priem 2016). Garriga (2014) suggests that understanding the objective or goals of stakeholder groups can identify what they value. Such a process is about finding common themes among company stakeholders regarding employability, autonomy, innovativeness, empathy, responsiveness, entrepreneurism, health, and environmental sustainability. Rather than focusing on the differences among the values of stakeholder groups, marketers can cultivate stakeholder value driver alignment to identify the drivers that intersect and offer opportunities to increase value for multiple stakeholders, without reducing value received by any other stakeholder group (Tantalo and Priem 2016).

Stakeholder value proposition

Sharing value among stakeholders also requires the ability to construct and balance the value propositions of all social and economic actors of a marketing system to gain a competitive advantage (Frow and Payne 2011). To create customer value, firms must formulate the value proposition to address a customer problem, articulate and communicate the value proposition, and manage the value proposition process (Skålén et al. 2015). Focusing on the communication aspect, Payne et al. (2017) define a customer value proposition as a “strategic tool facilitating communication of an organization’s ability to share resources and offer a superior value package to targeted customers” (p. 472), suggesting that organizational structures and processes for crafting value propositions are valuable resources.

While the idea of creating value for non-market stakeholders has gained some traction among marketing scholars, the concept of a stakeholder value proposition is relatively new. Furthering research in stakeholder value propositions, Ballantyne et al. (2011) posit that value propositions to firm stakeholders develop through a negotiation process. They argue that rather than the firm offering value propositions for stakeholders to accept or reject, stakeholder network participants must create mutual promises outlining the benefits expected to be gained and given up by each party. Stakeholder value propositions involve processes for dialogue and knowledge sharing that develop over time into system resources that lead to competitive advantages (Ballantyne et al. 2011; Frow and Payne 2011). Constructing value propositions to all system stakeholder groups requires both market sensing and information sharing activities to understand and share value.

Total value creation

The superiority of MSMO lies in the development of a cohesive stakeholder network. When a multiple stakeholder market-oriented firm facilitates the development of a network of interconnected stakeholders committed to a single value proposition, and stakeholders realize value in the network, it becomes more difficult for those with a competing notion of value to enter that network. That is, when the network is in place, there is less incentive for stakeholders to allow a new entrant into the network. This results in increased costs for those outside the network. These increased costs represent a barrier to network entry that decreases the potential advantages of entering the network for the new entrant. Thus, those that deploy the network reap the most benefit. The ability to do this effectively is the essence of MSMO.

As the focus of MSMO is a systems-orientation, value creation in MSMO accrues to two groups: the focal firm and the firm’s stakeholders. However, research on creating value for societal stakeholders is relatively new and as a result, the measurable outcomes are not well defined (Dembek et al. 2016). For example, while firms are typically focused on profit and sales, Ekman et al. (2016) find that stakeholders experience reputational effects from associating with members in a marketing system. Thus, because the idea of total value considers the entire marketing system, outcomes outside of profit and sales must be considered. Accordingly, we propose a shared value perspective regarding the outcomes of MSMO that includes reputation, innovation, and performance-based effects.

MSMO and reputation

Reputation refers to stakeholder perceptions of a company’s past actions and future prospects when compared to other competitors (Fombrun and Shanley 1990). A study of MO in nonprofits in India finds that market oriented organizations realize greater peer reputation for staying true to their mission, attracting financial resources, service/program delivery, and attracting staff and volunteers (Modi and Mishra 2010). Studies also support a positive relationship between stakeholder orientation behaviors and company reputation (Gonzalez-Padron et al. 2016; Maignan et al. 2011). Similarly, MSMO-adopting firms commit to creating value with stakeholders, generating trust and stability in the network, thereby enhancing the reputation of all organizations (Ekman et al. 2016; Frow and Payne 2011). Consequently, we propose that the total reputational effects of MSMO will create a sustainable competitive advantage due to stable and committed relationships with and among stakeholders.

MSMO and innovation

Innovation relates to the implementation of new ideas, products, and processes within a marketing system (Hurley and Hult 1998). The relationship between MO and innovativeness has been found to be positive and strong in nature (Paladino 2007). This relationship is attributable to the environmental scanning methods taken by organizations adopting such a strategic posture. That is, gathering competitor information and maintaining close connections with customers (followed by intra-organizational dissemination of relevant information), signifies a proactive approach to MO. Such an approach yields an innovation-based competitive advantage to the extent that knowledge of future customer needs and competitor offerings results in successful product innovations.

Likewise, a stakeholder orientation contributes greatly to innovative products and processes (Gonzalez-Padron et al. 2016; Maignan et al. 2011; Mena and Chabowski 2015). Additionally, a network competence in accessing resources, integrating communication, and fostering collaboration is important for achieving innovation success (Ritter and Gemünden 2003). Therefore, we propose that firms adopting MSMO will have a sustainable competitive advantage over those that are merely market oriented, as the network effects of associating and learning within a system create innovative outcomes for the stakeholder network.

MSMO and performance

A market orientation tends to have a positive effect on overall firm performance (e.g., Jaworski and Kohli 1993; Kumar et al. 2011). This is confirmed by both Rodriguez Cano et al. (2004) and Kirca et al. (2005), who find in separate meta-analytic studies that MO positively effects organizational performance and overall business performance. In terms of various measures of performance, Kumar and his colleagues find that although MO lifts both profit and sales (short and long-term), it has a larger effect on profit than sales due to MO’s focus on customer retention as opposed to customer acquisition.

Similarly, empirical studies support a positive influence on firm financial performance of investments in stakeholder relations (e.g., Graves and Waddock 2000), effective stakeholder management (e.g., Hillman and Keim 2001), and stakeholder-oriented behaviors (Gonzalez-Padron et al. 2016; Maignan et al. 2011). However, while marketing scholars have developed scales to measure economic, social, and environmental outcomes (e.g., Cronin et al. 2011), few empirical studies explore total value in a marketing system. Nevertheless, in qualitative research, Ekman et al. (2016) find that stakeholders experience network effects from energy reductions by increasing environmental awareness and the sense of belonging to a group that contributes to society. Thus, we posit that stakeholders of organizations that adopt a MSMO strategic posture will realize increased overall performance of their own, regardless of whether those organizations themselves adopt MSMO.

Operationalization

According to Churchill’s (1979) process for the development of marketing constructs, operationalization of a new construct includes specifying the construct’s domain and generating a sample of potential measurement items reflective of this domain. In this sense, the domain of MSMO is the S-D logic-based conceptualization of the marketing concept that differs from other market or stakeholder orientations. Accordingly, operationalization of MSMO relates to the three basic operant resources that require operationalization, including: (1) stakeholder orientation (prioritization of salient stakeholders; stakeholder intelligence generation and dissemination); (2) systems orientation (market sensing and network resource integration); and (3) shared value orientation (skills in stakeholder value alignment and stakeholder value proposition). Table 3 provides some suggestions for operationalizing MSMO based on the relevant literature.

A successful operationalization of MSMO also depends on an appropriate recognition of salient organizational stakeholders. However, because different industries are characterized by different stakeholder structures, it is unlikely that a single operational structure of MSMO exists. Thus, whereas relatively generic MO scales have been widely deployed across a vast number of firm and industry contexts, the added depth of MSMO may hinder its generalizability from an operational (though not conceptual) standpoint. As such, the critical component of any future investigations is that MSMO must be operationalized with respect to the focal organization’s key stakeholder constituencies. That is, because MSMO precludes the assumption of a homogeneous set of inter-industry organizational stakeholders, industry-specific operationalizations of MSMO must be conducted.

There are two approaches to operationalize salient stakeholders in research. First, a typology to prioritize stakeholders advocated by Mitchell et al. (1997) identifies salient stakeholders by their legitimacy, power, and urgency characteristics. According to Mitchell et al. (1997), a stakeholder has legitimacy only when its actions toward the firm are desirable or proper within the norms, values, and beliefs of the larger society. Ferrell et al. (2010) also include power in designating an organizational stakeholder as an actor with the power to give or take away resources necessary for the continuation of the organization’s activities. The final characteristic is urgency, defined as the extent to which a stakeholder calls for immediate attention by a firm. Salient stakeholders exhibit greater degrees of legitimacy, power, and urgency than other stakeholder groups. In a survey of CEOs, Agle et al. (1999) observe that managerial attention increased for a stakeholder group as perceptions of power, legitimacy, and urgency of the stakeholder group increased.

The second approach to identifying salient stakeholders includes evaluating the degree of attention the firm gives to specific stakeholder groups. Greenley and Foxall (1997) provide a measurement of company attention to stakeholders that includes five factors for each stakeholder group, including (1) the degree of formal research, (2) managerial judgment, (3) planned strategies to address interests, (4) corporate culture to engage in dialog, and (5) importance of stakeholder in corporate mission. Similarly, Maignan et al. (2011) include a ranking of importance of six stakeholder groups to generate a stakeholder orientation measure weighted by the firm’s prioritization of those stakeholders. Both approaches use self-reports of stakeholder salience. Other measurements include content analysis of company documents to determine attention to specific stakeholder groups (Gonzalez-Padron and Nason 2009).

Most stakeholder orientation operationalization for stakeholder information generation and stakeholder information dissemination follow Kohli and Jaworski’s MARKOR scale (Maignan and Ferrell 2004; Yau et al. 2007). However, the MSMO-based behaviors of information gathering and dissemination must go beyond the organization. Firms adopting a MSMO should pursue information across the spectrum of stakeholder markets and seek to share information externally as well as internally. For example, in a study of destination marketing organizations, Line and Wang (2017) measure stakeholder orientation information and dissemination with items such as “Our organization appreciates input from local politicians when setting strategic objectives” and “Our organization facilitates the flow of relevant information from our local government to the local industry” (p. 129).

The operationalization of MSMO must also consider a systems orientation that includes inter-organizational relationships with stakeholders. Two constructs form a system orientation: the ability to sense the market to learn about stakeholders and network resource integration to access, mobilize and deploy resources. Measures for market sensing should be multi-faceted to reflect an organization’s degree of open-minded inquiry, widespread information distribution, mutually informed interpretations, and memory accessibility (Day 1994a). Survey measures for resource integration should include the extent to which an organization has (1) access to resources, (2) resource adaptability to generate value, (3) resource mobilization that refers to the preparedness and willingness to exchange resources, and (4) the ability to internalize systems norms for resource integration (Laud et al. 2015; Sett 2017).

A shared value orientation considers the economic and social value accrued to all the stakeholders of the firm (Garcia-Castro and Aguilera 2015; Porter and Kramer 2011) and consists of two new constructs: stakeholder value driver alignment and stakeholder value proposition. The operationalization of a firm’s ability to facilitate stakeholder value driver alignment should reflect the ability to identify the stakeholder value drivers that intersect and offer opportunities to increase value for multiple stakeholders without reducing value received by any other stakeholder group (Tantalo and Priem 2016). Drawing from Ekman et al. (2016), new measures for stakeholder value driver alignment should assess how an organization considers system stakeholder’s (1) role (initiator, provider, or beneficiary); (2) value determination (monetary or non-monetary); and (3) perceived level of value creation (actor, dyad, or network). New measures for the ability to craft a stakeholder value proposition could be adopted from processes identified by Skålén et al. (2015) to include a reciprocal value proposition (Ballantyne et al. 2011).

Total value creation in MSMO consists of two groups: the focal firm and the firm’s network of stakeholders. Company performance could be self-reported through tested scales or through secondary sources such as financial reporting and social index databases. However, because MSMO is posited to yield a sustained competitive advantage for the focal firm greater than firms adopting only a MO, longitudinal studies of firm performance may be required to demonstrate whether companies adopting MSMO do, in fact, achieve greater performance than MO over time. The operationalization of MSMO in longitudinal studies could replicate existing longitudinal studies that include content analysis of company documents, interviews with managers, and engaging in ethnographic observation (e.g., Gebhardt et al. 2006; Noble et al. 2002).

MSMO is posited to create value for a firm’s stakeholders through reputation, innovation, and performance regardless of whether the stakeholder itself adopts a MSMO. By seeking information on the needs of stakeholders, companies are more likely to recognize opportunities to address stakeholder needs and create value for the company and its employees, suppliers and community stakeholders (Porter and Kramer 2011). However, because the measurement of the value created for a company’s stakeholders is challenging (Dembek et al. 2016), it may be difficult to link stakeholder performance outcomes to inter-organizational relationships with the focal firm.

Finally, operationalization of many of the components of MSMO can draw from existing scales with modifications. However, reliable measurements need to address the complexity of integrating stakeholder salience and total value creation in marketing research (Vargo et al. 2017). A cross-disciplinary review of like constructs or value calculation may generate new measurement or mapping techniques. Additionally, observing best-performing companies in creating shared value may provide insights into stakeholder salience and total value creation.

Implications

The purpose of conceptualizing a multiple stakeholder market orientation is to offer a comprehensive model to address stakeholder relationships in a dynamic business environment. MSMO mandates that organizations (1) generate, interpret, and react to information pertaining to the stakeholders’ interests in, and expectations of, the organization; and (2) communicate the results of these analyses to other relevant stakeholders. Accordingly, MSMO-based value creation emphasizes a systems orientation that includes inter-organizational relationships with stakeholders. Differing from other conceptualizations of market orientation and stakeholder orientation, MSMO considers the value generated for all stakeholders. Accordingly, the primary contribution of MSMO lies in its comprehensive approach to creating value for stakeholders. Unlike the extant conceptualization of market orientation, MSMO does not make any a priori assumptions regarding an organization’s salient stakeholder constituencies. Instead, by acknowledging the tenets of stakeholder marketing and the corresponding perspective of marketing as an activity enacted within a complex network of interorganizational relationships, MSMO considers value creation from a systems perspective (cf Lusch and Webster Jr 2011).

This conceptualization of MSMO has implications for marketing research and practice. The systems-theoretic perspective embedded in MSMO furthers marketing research to view phenomena at a micro, meso, and macro level. Advocating for a systems perspective in marketing, Vargo et al. (2017) identify four shifts in thinking about markets that lead to a research agenda that MSMO begins to address. As follows, we address how MSMO incorporates this type of systems thinking.

The first shift is about understanding the market as a whole, rather than a sum of independent parts. While most marketing research focuses on the manager or business transaction (the micro level), Layton (2011) suggests that a marketing system includes industry, brand or supply chain aggregates (the meso level), as well as the economy and society (the macro level). In terms of this perspective, Vargo et al. (2017) suggest “zooming out and zooming in on different levels of analysis” (p. 264) to explore how businesses and society interact. MSMO addresses this call by focusing business processes such as a stakeholder orientation (micro), broadening processes to include all stakeholders (meso), and creating shared value leading to social and environmental performance (macro).

The second shift is about recognizing the importance of relationships over transactions. A key research challenge is understanding “how the constellations of relationships are coordinated within markets” (Vargo et al. 2017, p. 264). The underlying theories of MSMO, S-D Logic and stakeholder marketing all place value on network relationships over individual transactions. To explore how such relationships are coordinated, the operationalization of MSMO should include a systems orientation that focuses on (1) cooperative and collaborative processes between actors and (2) shared value creation whereby all system stakeholders realize value.

The third shift is a movement away from a short-term focus on structures to a long-term perspective on emerging processes that influence and shape markets. Recent calls have encouraged researchers to include institutional complexity and market shaping through innovation (Vargo et al. 2017). The network effects of associating and learning within a system create innovative outcomes for both the stakeholder network and society. Accordingly, the present research aligns with this perspective and proposes longitudinal studies to foster a long-term perspective of MSMO-based processes and their outcomes.

Finally, there is a shift from measuring predictability and mapping patterns. Vargo et al. (2017) suggest that systems thinking requires “higher-order structures through lower-order activities” (p. 266) and that traditional methodological approaches may not explain the complexity of such a systemic perspective. Therefore, there are two considerations for the operationalization of MSMO. First, MSMO is a higher order strategic perspective, positing a comprehensive shared-value approach to total value creation. Second, mapping MSMO for companies could expose patterns and increase the understanding of the links between micro and macro levels of value (Kennedy 2017).

As previously discussed, marketing managers are called to respond to business model innovations such as the sharing economy, complex global supply chain configurations, and dynamic business conditions that challenge the firm’s competitive advantage (Hult and Ketchen 2017; Robertson 2017; Sett 2017). At the same time, pressures are increasing for firms to strategically address social and environmental issues by redefining business in terms of the value shared with communities (Porter and Kramer 2011). Building on stakeholder theory and shared value concepts, MSMO is thus positioned as a more broadly defined conceptualization of what it means to implement the stakeholder-marketing concept in the contemporary business environment.

A major difference between MSMO and the prevailing stakeholder perspectives is the focus on salient stakeholders, rather than the narrower focus on customers or a defined set of stakeholder groups. However, it is important to recall that the prioritization of stakeholders varies by industry as well as the level of scrutiny that a firm receives from the media, regulatory agencies, and activist groups. There is also a tendency to acknowledge and value a stakeholder defensively, in response to negative publicity or legislative action (Gonzalez-Padron and Nason 2009). Accordingly, the prioritization of stakeholder groups by an organization is central to understanding the managerial implications of the framework.

This research offers a conceptual definition of a multiple stakeholder market orientation as the behaviors that facilitate an organization-wide commitment to understanding and reacting to the needs of salient stakeholder markets for the purpose of total value creation. MSMO is posited to create value for a firm’s stakeholders through system-wide reputation, innovation, and social, economic and environmental performance; regardless of whether the stakeholder itself adopts a multiple stakeholder market orientation. By seeking information on the needs of stakeholders, companies are more likely to recognize opportunities to address stakeholder needs and create value for the company and its employee, supplier, and community stakeholders.

References

Agle, B. R., Mitchell, R. K., & Sonnenfeld, J. A. (1999). Who matters to CEOs? An investigation of stakeholder attributes and salience, corporate performance, and CEO values. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 507–525.

American Marketing Association (AMA): Marketing Power. (2017). Dictionary. Retrieved from: http://www.marketingpower.com/AboutAMA/Pages/DefinitionofMarketing.aspx

Bagozzi, R. P. (1975). Marketing as exchange. Journal of Marketing, 39(4), 32–39.

Ballantyne, D., Frow, P., Varey, R. J., & Payne, A. (2011). Value propositions as communication practice: taking a wider view. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 202–210.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm-resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Bharadwaj, N., & Dong, Y. (2014). Toward further understanding the market-sensing capability-value creation relationship. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(4), 799–813.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Korschun, D. (2008). Stakeholder marketing: Beyond the four Ps and the customer. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 27(1), 113–116.

Carpenter, G. S. (2017). Market orientation: reflections on field-based, discovery-oriented research. AMS Review, 7(1), 13–19.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73.

Clarkson, M. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92–117.

Cronin, J. J., Smith, J. S., Gleim, M. R., Ramirez, E., & Martinez, J. D. (2011). Green marketing strategies: an examination of stakeholders and the opportunities they present. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 158–174.

Day, G. S. (1994a). The capabilities of market-driven organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 37–52.

Day, G. S. (1994b). Continuous learning about markets. California Management Review, 36(4), 9–31.

Dembek, K., Singh, P., & Bhakoo, V. (2016). Literature review of shared value: a theoretical concept or a management buzzword? Journal of Business Ethics, 137(2), 231–267.

Dentoni, D., Bitzer, V., & Pascucci, S. (2016). Cross-sector partnerships and the co-creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(1), 35–53.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: concepts, evidence and implications. Academy of Management Review, 29(1), 65–91.

Edvardsson, B., Kleinaltenkamp, M., Tronvoll, B., McHugh, P., & Windahl, C. (2014). Institutional logics matter when coordinating resource integration. Marketing Theory, 14(3), 291–309.

Ekman, P., Raggio, R. D., & Thompson, S. M. (2016). Service network value co-creation: Defining the roles of the generic actor. Industrial Marketing Management, 56, 51–62.

El-Ansary, A., Shaw, E. H., & Lazer, W. (2018). Marketing’s identity crisis: insights from the history of marketing thought. AMS Review, 8(1–2), 5–17.

Ferrell, O. C., Gonzalez-Padron, T. L., Hult, G. T. M., & Maignan, I. (2010). From market orientation to stakeholder orientation. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 29(1), 93–96.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What's in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Friedman, A., & Miles, S. (2006). Stakeholders: Theory and practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frow, P., & Payne, A. (2011). A stakeholder perspective of the value proposition concept. European Journal of Marketing, 45(1–2), 223–240.

Garcia-Castro, R., & Aguilera, R. V. (2015). Incremental value creation and appropriation in a world with multiple stakeholders. Strategic Management Journal, 36(1), 137–147.

Garriga, E. (2014). Beyond stakeholder utility function: stakeholder capability in the value creation process. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(4), 489–507.

Gebhardt, G. F., Carpenter, G. S., & Sherry, J. F. J. (2006). Creating a market orientation: a longitudinal, multifirm, grounded analysis of cultural transformation. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 1.

Gonzalez-Padron, T. L. (2017). Ethics in the sharing economy: creating a legitimate marketing channel. Journal of Marketing Channels, 24(1/2), 84–96.

Gonzalez-Padron, T. L., & Nason, R. W. (2009). Market responsiveness to societal interests. Journal of Macromarketing, 29(4), 392–405.

Gonzalez-Padron, T. L., Hult, G. T. M., & Ferrell, O. C. (2016). A stakeholder marketing approach to sustainable business, in marketing in and for a sustainable society: Emerald.

Graves, S. B., & Waddock, S. A. (2000). Beyond built to last ... Stakeholder relations in "built-to-last" companies. Business and Society Review, 105(4), 393.

Greenley, G. E., & Foxall, G. R. (1997). Multiple stakeholder orientation in UK companies and the implications for company performance. Journal of Management Studies, 34(2), 260–284.

Greenley, G. E., Hooley, G. J., & Rudd, J. M. (2005). Market orientation in a multiple stakeholder orientation context: implications for marketing capabilities and assets. Journal of Business Research, 58(11), 1483–1494.

Gundlach, G. T., & Wilkie, W. L. (2010). Stakeholder marketing: why "stakeholder" was omitted from the American Marketing Association's official 2007 definition of marketing and why the future is bright for stakeholder marketing. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 29(1), 89–92.

Hillebrand, B., Driessen, P., & Koll, O. (2015). Stakeholder marketing: theoretical foundations and required capabilities. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(4), 411–428.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: what's the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 125.

Hult, G. T. M. (2011a). Market-focused sustainability: Market orientation plus! Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 1–6.4.

Hult, G. T. M. (2011b). Toward a theory of the boundary-spanning marketing organization and insights from 31 organization theories. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(4), 509–536.

Hult, G. T. M., & Ketchen, D. J. (2017). Disruptive marketing strategy. AMS Review, 7(1), 20–25.

Hult, G. T. M., Mena, J. A., Ferrell, O. C., & Ferrell, L. (2011). Stakeholder marketing: a definition and conceptual framework. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1, 44–65.

Hunt, S. D. (1976). The nature and scope of marketing. Journal of Marketing, 40(3), 17–28.

Hurley, R. F., & Hult, T. M. (1998). Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: an integration and empirical examination. Journal of Marketing, 62(3), 42–54.

Jaworski, B. J., & Kohli, A. K. (1993). Market orientation: antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing, 57, 53–70.

Jaworski, B. J., & Kohli, A. K. (2017). Conducting field-based, discovery-oriented research: lessons from our market orientation research experience. AMS Review, 7(1), 4–12.

Jaworski, B., Kohli, A. K., & Sahay, A. (2000). Market-driven versus driving markets. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 45–54.

Johnston, A. (2013). Walmart targets ambitious renewable energy, energy efficiency standards by 2020. Clean Technica, April 23, (accessed April 24, 2015), [available at https://www.cleantechnica.com].

Kennedy, A.-M. (2017). Macro-social marketing research. Journal of Macromarketing, 37(4), 347–355.

Kirca, A. H., Jayachandran, S., & Bearden, W. O. (2005). Market orientation: a meta-analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and impact on performance. Journal of Marketing, 69(2), 24–41.

Kohli, A. K., & Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market orientation: the construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 1–18.

Kohli, A. K., Jaworski, B. J., & Kumar, A. (1993). MARKOR: a measure of market orientation. Journal of Marketing Research, 30(4), 467–477.

Kotler, P. (1972). A generic concept of marketing. Journal of Marketing, 36(2), 46–54.

Kull, A. J., Mena, J. A., & Korschun, D. (2016). A resource-based view of stakeholder marketing. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5553–5560.

Kumar, V., Jones, E., Venkatesan, R., & Leone, R. P. (2011). Is market orientation a source of sustainable competitive advantage or simply the cost of competing? Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 16–30.

Laczniak, G. R., & Murphy, P. E. (2012). Stakeholder theory and marketing: Moving from a firm-centric to a societal perspective. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 31(2), 284–292.

Laszlo, C., Sherman, D., Whalen, J., & Ellison, J. (2005). Expanding the value horizon: how stakeholder value contributes to competitive advantage. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship (20), 65.

Laud, G., Karpen, I. O., Mulye, R., & Rahman, K. (2015). The role of embeddedness for resource integration. Marketing Theory, 15(4), 509–543.

Layton, R. A. (2011). Towards a theory of marketing systems. European Journal of Marketing, 45(1/2), 259–276.

Line, N. D., & Wang, Y. (2017). Market-oriented destination marketing. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 122–135.

Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2006). Service-dominant logic as a foundation for a general theory. In R. F. Lusch & S. L. Vargo (Eds.), The service-dominant logic of marketing (pp. 406–420). Armank: M.E. Sharpe.

Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2011). Service-dominant logic: a necessary step. European Journal of Marketing, 45(7/8), 1298–1309.

Lusch, R. F., & Webster Jr., F. E. (2011). A stakeholder-unifying, co-creation philosophy for marketing. Journal of Macromarketing, 31(2), 129–134.

Madhavaram, S., & Hunt, S. D. (2008). The service-dominant logic and a hierarchy of operant resources: developing masterful operant resources and implications for marketing strategy. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 67–82.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and marketing: an integrative framework. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 32(1), 3–19.

Maignan, I., Ferrell, O. C., & Ferrell, L. (2005). A stakeholder model for implementing social responsibility in marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 39(9/10), 956.

Maignan, I., Gonzalez-Padron, T. L., Hult, G. T. M., & Ferrell, O. C. (2011). Stakeholder orientation: development and testing of a framework for socially responsible marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 19(4), 313–338.

Matsuno, K., & Mentzer, J. T. (2000). The effects of strategy type on the market orientation-performance relationship. Journal of Marketing, 64(4), 1–16.

Matsuno, K., Mentzer, J. T., & Rentz, J. O. (2000). A refinement and validation of the MARKOR scale. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(4), 527–539.

Mena, J., & Chabowski, B. (2015). The role of organizational learning in stakeholder marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(4), 429–452.

Mish, J., & Scammon, D. L. (2010). Principle-based stakeholder marketing: Insights from private triple-bottom-line firms. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 29(1), 12–26.

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853.

Mizik, N., & Jacobson, R. (2003). Trading off between value creation and value appropriation: the financial implications of shifts in strategic emphasis. Journal of Marketing, 67(1), 63–76.

Modi, P., & Mishra, D. (2010). Conceptualising market orientation in non-profit organisations: definition, performance, and preliminary construction of a scale. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(5/6), 548–569.

Morgan, N. (2012). Marketing and business performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 102–119.

Narver, J. C., & Slater, S. F. (1990). The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. Journal of Marketing, 54(4), 20–35.

Narver, J. C., Slater, S. F., & MacLachlan, D. L. (2004). Responsive and proactive market orientation and new-product success. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 21(5), 334–347.

Nestlé S.A. (2017). Nestlé in society: Creating shared value and meeting our commitments 2016 Retrieved from Nestlé S.A., Avenue Nestlé 55, Vevey 1800, Switzerland.

Ngo, L. V., & O’Cass, A. (2009). Creating value offerings via operant resource-based capabilities. Industrial Marketing Management, 38(1), 45–59.

Noble, C. H., Sinha, R. K., & Kumar, A. (2002). Market orientation and alternative strategic orientations: a longitudinal assessment of performance implications. Journal of Marketing, 66(4), 25–39.