Abstract

Seepage lakes lacking surface-water inflow or outflow, but with surrounding peatlands, are important and vulnerable ecosystems with water budgets that depend largely on inputs from precipitation and groundwater discharge. We studied the sediment diversity in two such lake-wetland systems and their surrounding catchments. The lakes were located in relatively close proximity to one another within the West Polesie Transboundary Biosphere Reserve, West Polesie, East Poland. In spite of physiographic similarities, the studied lake-wetland systems and their catchments displayed considerable diversity in their underlying sediments. This was determined from data collected from several hundred geological boreholes and 164 determinations of the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the organic and mineral sediments (constant and falling head methods). Our research results showed that the functioning of a closed lake-wetland ecosystem is greatly influenced by the hydrogeological properties of its sediments. In the case of wetland zones surrounding lakes, especially closed-drainage seepage lakes, it is very important to identify the geological settings and the hydrogeological properties of those sediments in order to better understand groundwater influences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding the direction and rate of water movement is important in researching catchments where lakes are surrounded by wetlands (Dembek and Oświt 1992). Research on water inflow to lakes usually includes the determination of water exchange and hydrologically active zones (Cheng and Anderson 1994; Shaw and Prepas 1990; Hunt et al. 1999; Winter 1999; Hunt et al. 2003; Choiński 2007). This is usually based on detailed analyses of surface and groundwater inflows and outflows (Sacks et al. 1992; Hunt and Krohelski 1996; Walker and Krabbenhoft 1998; Ojiambo et al. 2003; Stets et al. 2010). In the case of surface-water components of the water balance, studies often focus on direct precipitation to the lake surface and the intensity of surface runoff. However, assessment of the groundwater component is more difficult, but can be estimated through analysis of aquifer contact with the lake. According to Choiński (2007), three types of interaction of groundwaters with lake waters exist: direct contact (when the aquifer contacts directly with lake water as a result of existing hydraulic gradients), inflow of waters under hydraulic pressure (usually in the lake bottom), and submerged spring mixing (Cieśliński et al. 2016).

A case involves groundwater inflow to lakes surrounded by wide wetland zones. These lakes are in the last stage of succession and provide model subjects for understanding factors influencing the genesis and development of wetlands (Lange 1993). Over time, the accumulation of matter in a lake basin results in its filling, and in the process, water is replaced by organic and mineral sediments. Water inflow to a lake that is being infilled with biogenic sediments is subject to transformation. The spatial distribution of particular hydrogeological zones within the infilling lake basin and its catchment affects the time of response of lake waters to precipitation, inflow from the surface and groundwaters, and the input of mineral and organic matter. In such areas, the extent and depth of the wetland zone within the basin does not constitute a hydrogeologically uniform layer – it includes both mineral and organic sediments with different capacities for hydrologic conductivity and accumulation.

Generally, in catchments where considerable areas between the water divide and the lake edge are occupied by wetlands (e.g., peatlands), sediment permeability can vary greatly (Gerla 1999; Krohelski et al. 2002; Beckwith et al. 2003; Ferone and DeVito 2004; Rudnick et al. 2015). Research concerning the importance of wetlands in the water balance of closed-drainage lakes is limited, largely due to difficulties determining the contribution of groundwater inflow to lakes. This is particularly true of lakes surrounded by large areas of peatlands and gyttja. Shallow, small, and infilling (i.e., terrestrializing) lakes are areas where research on water inflow should be supported by a detailed analysis of the primary lake basin and the sediments filling it. Some studies (i.e. Townley and Trefry 2000; Smerdon et al. 2005) have examined the effect of groundwater on the water balance of lakes. An important aspect of this research has been determining the role of the surrounding wetlands in shaping the water balance. The identification of the hydrologically active elements of the lake basin, together with analyses of sediments and the semi-liquid sediments deposited on the bottom of lakes, is necessary for a detailed analysis of the zone of hydrological contact of lakes and wetlands. We explored the hydrogeological properties of mineral and organic deposits of two infilling lake basins and their catchments in the Łęczna-Włodawa Lake District of West Polesie, East Poland to determine whether water circulation is modulated between the lake catchments, the surrounding wetlands and the lakes themselves.

Study Area

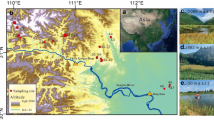

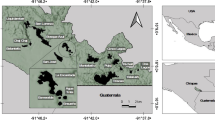

This study was conducted in the Łęczna-Włodawa Lake District, constituting the westernmost fragment of a large European region known as West Polesie (Poland, East Europe). The area is characterized by a great number of lakes, marshes, meadows, swamps and lake complexes. The primary feature of the area is the occurrence of a near-surface groundwater table resulting from shallow deposition of impermeable sediments (particularly muds and clays). Such conditions determine groundwater circulation in lake catchments (subsurface flow) under the strong influence of the local atmospheric conditions (especially precipitation, temperature and evaporation). The lakes, together with the surrounding wetlands, constitute one of the most ecologically valued components of the landscape of Polesie, and form one of only a few groups of lakes in Poland and Europe located outside the margin of the ice sheet of the last glaciation (Vistulian glaciation, also known as the Weichselian). Due to its uniqueness, and hydrological and hydrogeological character, this area, including the two analysed lake catchments, was incorporated within the borders of the West Polesie Transboundary Biosphere Reserve in Poland, Ukraine and Belarus (Chmielewski et al. 2014).

It is estimated that more than 80% of lakes in the Łęczna-Włodawa Lake District are surrounded by peatlands and gyttja (Turczyński et al. 2009). Thicknesses of the organic sediments can reach approximately 12 m. Diverse formations and sequences of layers within these peatlands and the surrounding lake-catchment suggest variable hydrologic conditions (Wojciechowski 1991). Lake Czarne Gościnieckie and Lake Brzeziczno are located in the western part of the Łęczna-Włodawa Lake District (Fig. 1). Both are distinguished their extensive wetland areas, as well as by their lack of surface outflow, stage of lake development (in final stage leading to transformation to wetlands) and low degree of anthropogenic influence. The entire West Polesie, including the two lake basins, were shaped by four Pleistocene glacial advances that resulted in a very high diversity of sediments, both in lithological and stratigraphic terms (Harasimiuk et al. 2002; Bałaga 2003). Hence, the area is dominated by relatively flat accumulation and accumulation-denudational landforms. Both of the lakes are of polygenetic genesis. According to the latest study results, their development was influenced by tectonic factors and the hydrogeological specificity of the Upper Cretaceous massif (Dobrowolski 2006).

Lake Czarne Gościnieckie

Lake Czarne Gościnieckie is the westernmost natural lake in West Polesie. It is a small closed-drainage lake approximately 12 ha in area, with a water surface at 150.00 masl. Its catchment to lake area ratio is 7.47 with a maximum depth and volume of 1.80 m and 130,200 m3, respectively. Lake Czarne Gościnieckie is distinguished by its surrounding peatland (25.5% of the total lake and catchment area), forest-covered catchment (57.1% of the total lake and catchment area) and lack of human settlement. Moreover, the 82.80 ha catchment of Lake Czarne Gościnieckie is one of the smallest catchment areas in the Lake District. Geologically, the catchment is dominated by sands and fluvio-periglacial muds that occupy almost 40% of the total catchment area. Underlying these sands and muds is a layer of hydrated silty sands that usually constitute the local aquifer. The basin of Lake Czarne Gościnieckie and its surrounding peatland is composed of peaty muds and transitional peats. The organic sediments show considerable diversity and vary in thickness from 0.1 to 12.1 m. Sedimentation of the lake basin began ~13,000 yrs BP at the end of the Vistula Glaciation (Bałaga 2003).

The lake is strongly overgrown, indicating that it is in the last stage of its transition to peatland (Michalczyk 1998). Of the 1,310 m lake shoreline, more than 75% of its entirety is difficult to accurately delineate. The width of the wetland (i.e., peatland) belt surrounding the lake varies from approximately 10 m (eastern part of the shore), up to 460 m (south-western part) and occupies an area of more than 20.5 ha. The wetland vegetation is mainly dominated by sedges typical of transitional bogs, specifically an assemblage of slender sedge (Caricetum lasiocarpae) and Ledo-Sphagnetum magellanicini. (Sugier 1998). The later is rarely encountered in Poland. Due to its high ecological value, the Lake Czarne Gościnieckie and its catchment were incorporated in the Natura 2000 network as a special protection area: “Lasy Parczewskie” (PLB060006).

Lake Brzeziczno

Lake Brzeziczno, is also a small (approximately 8.3 ha, with volume of 111,800 m3, water surface at 168.10 masl and catchment-lake area ratio = 85.11), shallow (2.3 m) closed-drainage lake in the final stages of transformation to wetland (Turczyński et al. 2009). In elevation, Lake Brzeziczno is the highest-located lake in the region. Its basin is filled with a thick layer of organic sediments. Its 409-m shoreline is weakly developed making its accurate delineation difficult to near-impossible (Turczyński et al. 2009). The difficulty in determining the lake edge results from the fact that the lake is, from all sides, surrounded by peatland Additionally, an acidic, floating-vegetation mat intrudes onto the water surface. The lake is distinguished by its compact shape, small volume, and sub-circular shaped basin. Physical-chemical water analyses performed from 2000 to 2008 revealed that the lake is humoeutrophic according to the Hydrochemical Dystrophy Index (HDI; Chmiel 2009).

The 706.4 ha catchment of Lake Brzeziczno is characterized by a forest-agricultural land use (forests 53% and arable land 30% of the total catchment area). The peatland, partially overgrown by European white birch (Betula pubescens EHRH) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) occupies the area immediately surrounding the lake. The shores of the Lake Brzeziczno basin are made up of peaty muds that have formed an extensive flat area where a peatland has formed. The peatland is composed of various organic sediments (among others, peats and gyttjas), frequently interlayered with mineral formations. Sediment thickness varies from 0.1 m to approximately 8.5 m. On the eastern shore of the lake, shallow deposits of fen incorporating peat (maximum thickness of near 2.0 m) have developed. This fen area occupies approximately 15.6 ha and is the most frequently encountered type of wetland in this part of Polesie. Among mineral formations in the lakes basin and catchment, the largest area is occupied by lacustrine and fluvial sands (near 65% of the catchment). These sediments are composed of particularly fine- and medium-grained sands with fine gravels, interlayered with silty sands.

Lake Brzeziczno is surrounded by a transitional and raised bog with an area of approximately 58 ha. The peatland is surrounded by a subcontinental fresh pine coniferous forest (Peucedano-Pinetum) and a Subatlantic fresh pine coniferous forest (Leucobryo-Pinetum) (Fijałkowski 1996). In 1959, the lake, together with the surrounding peatland, was made into an 87.46 ha natural reserve due to its valued flora. The catchment of Lake Brzeziczno is also protected by its inclusion in the “Pojezierze Łęczyńskie” Landscape Park and the CORINE Refuge “Pojezierze Łęczyńsko-Włodawskie” and is considered an area of international importance within the ECONET-PL network.

Material and Methods

We determined the types, thicknesses and ranges of sediments at 464 locations within the two lakes (Czarne Gościnieckie - 51, Brzeziczno - 28) and their surrounding wetlands (Czarne Gościnieckie - 117, Brzeziczno - 119) and catchment areas (Czarne Gościnieckie - 80, Brzeziczno - 66) (Figs. 2 and 3). At each sample location, we used a spiral auger or Edelman hand auger to collect sediment samples to depths ranging between 0.1 and 12.0 m. In areas of unconsolidated bottom sediments, we used a Beeker’s sampler for sediment collection. Collection of organic sediments was performed to the top of the mineral substrate, both on land and within the lake basin for the purpose of determination of occurrence of biogenic sediments and for the identification of organic sediments. Sediment type was determined based upon their dominant composition and physical properties using the macroscopic methods of Okruszko and Troels-Smith (Troels-Smith 1955; Okruszko 1976; Ilnicki 2002).

The type of water movement, whether laminar or turbulent, was determined using piezometers via a modified test pumping method (see van der Schaaf 2004). In sediments where water movement was laminar, hydraulic conductivity (k) served as the basic parameter for permeability. Sediment permeability was used to identify hydrologically active areas (Rycroft et al. 1975; Tiner 1999; Malinowska and Hyb 2004; Iwanek 2005; Jaros 2006; Rosa and Larocque 2008; Żurek 2010). Such hydrologically active areas were later sampled via coring for detailed hydraulic conductivity analysis. In addition, selected piezometer monitoring of groundwater levels enabled us to produce a groundwater contour map for the lake catchments that revealed the directions of groundwater movement.

The hydrogeological properties of the sediments filling the lake basin and its shores were assessed using laboratory permeameter (Eijkelkamp, Netherlands). The laboratory permeameter allowed the measurement of saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ksat) of organic and mineral formations in the saturated state. We collected 100 cm3 of undisturbed-structure sediments (using soil sample stainless steel ring sets), either from the ground surface or from hydrogeological corings (to 12.0 m). The material was then transferred to sample rings (of 5.0 cm height and 5.3 cm diameter, cross-section surface of the sample - constant value 19,625 cm2). Two methods were applied to determine the saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ksat) of the sampled sediments (Rogoż 2012): a) measurement at a constant water level (constant head test) - this method was used in establishing Ksat in highly permeable formations (e.g. medium-grained sands), b) measurement at a variable water level (falling head test) - this method was used for medium and low permeable sediments (e.g. peats, peaty muds). If the samples were not subject to saturation after eight weeks (due to very low permeability), measurement could not be performed and the sample was assumed to have extremely low Ksat. The geological formation variability of saturated hydraulic conductivity conditions was determined based on the analysis of 76 samples (Lake Czarne Gościnieckie catchment), and 88 samples (Lake Brzeziczno catchment) of mineral and organic sediments taken from both the terrestrial and water part of the lake basins (in the period of ice cover on the lakes).

The potential for groundwater movement in the studied catchments was determined based on spatial analysis of hydrogeological parameters of particular sediments. The main groups of geological formations were ascribed mean values of Ksat measured in the laboratory.

Results

The results of our study showed that both of the lakes – Czarne Gościnieckie and Brzeziczno – are currently closed-drainage lakes. The lack of stream inflows and outflows has eliminated a component of the water balance. Due to the flatness of the surrounding terrain, surface runoff does not play a considerable role in lake inflow. Water drainage in the catchments, however, is observed in situations when snow melting occurs on the frozen layer of the peatland. A complex system of drainage routes is particularly visible in winter periods, as the complicated hummock-hollow structure of the surface of the peatland forces the development of specific routes of meltwater transport (Iwanow 1953, Frei et al. 2010). However, such inflow was not measured during the current research.

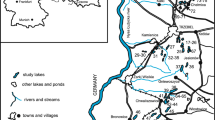

The period of study (2009–2011) had almost 22% higher annual precipitation totals than the long-term mean (525 mm; 1951–2000) in the Łęczna-Włodawa Lake District (Fig. 4 B1 and B2). In addition, frequent thaws, simultaneous with varied rainfall, occurred during the winter seasons. Our analysis of lake water-level fluctuation showed that this did not directly react to rainfall. Our data also showed that the groundwater tables in the organic and mineral sediments (in selected piezometres) essentially reflected the dynamics of the lake water levels, as these were characterised by an increasing trend, albeit with high monthly variability. We found that the shape of the shallow (quaternary) groundwater table of both lake catchments conformed, in general, to the surface topography (Fig. 4 A1 and A2. Measurements recorded in the Czarne Gościnieckie Lake catchment (mean value of lake water level - 152.34 masl) showed that the top of the water table (about 70% of the total area of catchment) was at an elevation between 152.00 and 153.00 masl. Furthermore, outflow from this area was generally in the north direction, towards the Bobrówka river valley Fig. 4 A1). In spring 2010, the mean value of the water level in Lake Brzeziczno (170.95 masl) was above that of the adjacent Lake Piaseczno, and the central and eastern part of the Lake Brzeziczno catchment drained to Lake Piaseczno, while the western part of the catchment drained to the neighbouring Lake Rogóźno catchment (Fig. 4 A2). Towards the west, the groundwater divide was dislocated towards the east with reference to the topographic water divide. In the studied catchment, recharge (feeding) was possible only from the northern and southern divide zones. The complexity of the hydrogeology of both lakes is indicated in Fig. 4a.

Groundwater table elevations and fluctuations in catchments of two lakes in West Polesie, East Poland: a groundwater table elevations in catchments and their vicinity for (A1) Lake Czarne Gościnieckie (surface elevation on 17 Apr 2010 = 152.34 masl) and (A2) Lake Brzeziczno (surface elevation on 26 April 2010 = 170.95 masl); b water table fluctuation in the lakes and in the organic and mineral sediments contrasted with the monthly precipitation in 2009–2011 for (B1) Lake Czarne Gościnieckie and (B2) Lake Brzeziczno

Hydraulic Conductivity

The saturated hydraulic conductivity determined by means of the laboratory permeameter showed very high variability, not only between particular sediments, but also within the same type of formation (Tables 1, 2, Fig. 5).

The calculated mean Ksat in mineral formations occurring in the catchment of Lake Czarne Gościnieckie showed that many types of sediment have very low Ksat (muddy sands, muds with high amounts of fine sand) and may be considered impermeable layers. Other sediments, such as the various-grained sands, had very high saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ksat =1.1·10−3 m·s−1) (Table 1).

Considerably higher variability in Ksat was observed in the organic sediments. The analysed peat samples, irrespective of their type, were distinguished by similar values of saturated hydraulic conductivity, varying from 1·10−4 to 3·10−4 m·s−1. Gyttja sediments, however, showed a higher variability of the saturated hydraulic conductivity. This was particularly determined by the depth of location of the layer, its degree of hydration and its micro-vegetal content. The highest values of saturated hydraulic conductivity were recorded in the shallowest, usually strongly hydrated, algal-detritus gyttja (2.6·10−3 m·s−1). In sediments of more compact algal-detritus gyttja, those with visible micro-vegetal remains had higher Ksat (2.1·10−3 m·s−1) in contrast to those without micro-vegetal remains (2·10−4 m·s−1). Compact and very compact algal-detritus gyttjas, usually located in the bottom layer of the organic sediments, had the lowest Ksat values (6.1·10−7-1.13·10−6 m·s−1). In general, the carbonate loam had very low Ksat (Fig. 5) and could be considered impermeable. Carbonate loam was the deepest analysed sediments of the studied areas and the samples were not subject to saturation, i.e. they did not meet the requirements of the study.

The hydrogeological parameters of sediment samples collected from Lake Brzeziczno and its catchment also showed high variability of saturated hydraulic conductivity, both within mineral and organic formations (Table 2). The mean saturated hydraulic conductivity of sandy formations varied from 6·10−8 to 8·10−4 m·s−1. The muddy sands with a high amount of fine sand and hardpan (Ksat = 6·10−8 m·s−1) showed the lowest Ksat values. Generally, all the muds underlying organic sediments in the analysed catchment had very low Ksat. These, e.g. muds with a small admixture of fine sand or silty muds, were also practically impermeable (Ksat =2·10−9 m·s−1), and some of the analysed samples were not even subject to saturation.

Our analyses of organic formations revealed considerably higher Ksat values in peat sediments, as compared to the gyttjas. The highest saturated hydraulic conductivities were recorded for weakly decomposed reed peats (Ksat = 1.3·10−3 m·s−1) and moss peats (Ksat = 1.2·10−3 m·s−1). The lowest saturated hydraulic conductivities were determined for sedge-reed peats (Ksat = 5·10−5-1.1·10−3 m·s 1). Among algal-detritus gyttjas, the highest saturated hydraulic conductivity rate were observed for strongly hydrated sediments (Ksat = 2·10−4 m·s−1) and loose sediments with a high amount of visible vegetal remains (Ksat = 1·10−3 m·s−1). Gyttjas sampled from the bottom layers were distinguished by their very low saturated hydraulic conductivities (Ksat = 2.2·10−7-1.28·10−5 m·s−1). Moreover, low values of saturated hydraulic conductivity were also seen in the case of organic-mineral peaty muds (Ksat = 2.28·10−6 m·s−1) (Fig. 5):

Hydrogeological Parameters of Sediments

We identified sediments representative of six hydraulic-conductivity classes (Table 3). This provided the basis for the determination of hydraulic-conductivity classes, and this approach is partially based on the method proposed by Pazdro and Kozerski (1990). However, measured Ksat obtained for the same type of sediment in each catchment were frequently different (Tables 1 and 2). For example, sandy formations (fine, various grained) were classified to a group with very high permeability in the catchment of Lake Czarne Gościnieckie (Ksatmean = 1.1·10−3 m·s−1), and to a group with high permeability in the catchment of Lake Brzeziczno (Ksatmean = 6·10−4 m·s−1). Due to this, the analysis of potential conditions of water movement was conducted for each catchment separately, using the obtained values of saturated hydraulic conductivity specific to the catchments. The ranges of values for particular classes of hydraulic conductivity were identical for each of the studied areas (Table 3):

The analysis of the permeability conditions of sediments for Lake Czarne Gościnieckie revealed that the surface layers of the analysed area were distinguished by their very-high permeability (Fig. 6). The hydrated sediments of algal-detritus gyttja that fill the basin of the lake in its current state was categorised to the same class. High permeability was also determined for peats, although lower Ksat values were associated with increased decomposition of the organic sediments.

We found a complex system of layers with various degrees of saturated hydraulic conductivity in the north-western part of the peatland in the Lake Czarne Gościnieckie catchment. This area is distinguished by the highest variability of particular layers of formations. Much lower permeability was observed in the sediments at the bottom of the central part of the basin where biogenic accumulation occurred. Loose and compact algal-detritus gyttjas and very well decomposed compact peats were very evident in this area. In the lake basin, organic sediments usually overlaid sediments with very low Ksat (i.e. carbonate loam) and could be considered as impermeable (Fig. 6a). There was no evidence of carbonate loam sediments in the cores taken in the south-eastern part of the Lake Czarne Gościnieckie catchment.

The existing sediment layers in the Czarne Gościnieckie Lake catchment, distinguished by such variable hydraulic conductivity, leads to the lack of possibility of inflow to the lakes, of waters through their bottoms (Fig. 6a). The impermeable muds developing the shores of the lake also limit groundwater flow from deeper aquifers. Water movement can, therefore, only occur in the surface layers of the catchment (as shallow groundwater flow). In the water divide zones, the water circulates in sandy formations; on peatlands, its movement is recorded in the acrotelm zone (in the near-surface layer of the undisturbed peatland, containing living plants); and, in the current lake basins, within strongly hydrated algal-detritus gyttja.

In the Lake Brzeziczno catchment, the existence of impermeable layers disturbs groundwater discharge and affects the complexity of the water circulation process (Fig. 6b). The highest permeability was observed in the surface formations developed within the biogenic accumulation reservoir. Such high values of the majority of peats suggest potential fast water retention by the sediments. The sands within the water divide zones, and the strongly hydrated algal-detritus gyttja in the lake, however, show lower permeability. In addition, the weakly decomposed sedge-reed peats constituting a considerable part of the peat deposit, show medium permeability. Loose sediments of algal-detritus gyttja, however, are semi-permeable and have the lowest permeability of the organic sediments. The algal-detritus gyttja occurred on very permeable moss peat sediments. The deepest layers of considerable parts of the lake basin and its shores are impermeable silty muds and muddy sands. These layers do not extend continuously across the basin. Rather they are frequently interrupted with zones with higher hydraulic conductivity permitting water runoff and inflow to the lake.

Water exchange in the catchment of Lake Brzeziczno mostly occurs in its near-surface layers. Water discharge within the surrounding peatland is determined by a mosaic of sediments with varied hydraulic conductivity. The existence of hydrogeological windows in the sides of the geologic lake basin permit potentially large groundwater exchange to lakes. The movement, however, is considerably limited by thicker sediments of semi-permeable and compact gyttja.

Discussion

The hydrogeological research performed in the selected catchments showed a complicated pattern of water relations resulting from the complex geological structure. The type of geological formations in the selected catchments and the varied hydraulic gradients reveal that within the analyzed sediments, water movement is largely laminar in character (in the sense of fluid dynamics). However, in some parts of the catchment, particularly in sandy sediments, the critical groundwater flow velocity was exceeded, suggesting that turbulent or mixed type of water movement may occur.

Mineral and organic formations in both of the studied catchments were distinguished by varied lithological and hydrogeological properties. These have consequences in water circulation. The identification of types of sediments, and then their hydrogeological parameters permitted the determination of water-movement potential (particularly in zones of contact of groundwaters circulating in mineral sediments with waters filling peat massifs).

The obtained values are typical of particular formations and are in broad accordance with data presented by other researchers (i.a. Dai and Sparling 1973, Päivänen 1973, Zawadzki and Olszta 1977, Kellner 2007, Petrone et al. 2008, Malloy 2013, Rydelek et al. 2014, Thompson et al. 2015). Our determinations of saturated hydraulic conductivity were conducted for profiles in particular sediment layers separately, not generally for a whole profile. This methodology is found sporadically in the research of wetlands ecosystems but gives comprehensive information about the potential for groundwater movement in such ecosystems - in some, groundwater movement is possible, and in some, it is limited or impossible.

Some of the sediments surrounding both of the lakes in their current condition constitute an evident barrier isolating the lake waters from waters moving towards the lake from the groundwater retention zone. The group of impermeable sediments in the case of the studied lakes included silty muds and muds with a small admixture of fine sand, loams, as well as carbonate loams. In the analysed catchments, the impermeable sediments usually constitute the bottom layer – below the deposited organic sediments. Impermeable sediments also occur at near surface in the catchment water-divide. The surface layer of the outermost edge of the catchments were composed of highly and very highly permeable sandy formations of variable granulometric composition. In contrast, the group of sediments that displayed high hydraulic conductivity included the majority of the analysed peats and strongly hydrated gyttjas. These sediments formed zones enabling water inflow to the lakes, albeit, some potential water movement is thought to occur through the basin sides of Lake Brzeziczno through hydrogeological windows.

We found that groundwater recharge of the studied lakes could generally occur through the upper layers of organic sediments (shallow groundwater flow), constituting deposits of peats of various types. This is because the majority of sediments filling these lake basins are impermeable or semi-permeable for water inflowing to the lakes themselves. Moreover, our results reveal the need to consider surrounding wetlands in lake studies so as to better understand the inflows of groundwater. Wetlands, being areas characterized by great retention potentials, profoundly influence the relative hydrological stability of small and shallow lakes. Thus, our results indicate that water circulation in small catchments is crucial for the lake-wetland ecosystem, especially in wetlands such as those we studied in West Polesie.

The functioning of a closed lake-wetland ecosystem is greatly influenced by the hydrogeological properties of the sediments. In the case of wetland zones surrounding lakes, especially closed-drainage seepage lakes, it is very important to identify the geological settings and the hydrogeological properties of the sediments as best as possible. In these lakes, natural hydrogeological isolation of the catchment brings about a situation in which the water inputs to the lakes and surrounding wetlands almost solely depend on precipitation. Water deficits result as plants (trees and bushes) encroach into the wetland zone adjacent to lake. However, retention of abundant water reserves in those zones brings about their long-time inundation and plant decay. Understanding such ecosystems is basic for the future protection and conservation activities of unique landscapes.

Unfortunately, these valuable lake-wetland systems have experienced adverse human impacts for over the past 200 years. Coal mining and draining of wetlands for agriculture purposes, as well as tourist developments, have engendered strong degradation of these systems and brought about often irreversible changes in the environment. Such situations are exacerbated by weak and inadequate state of knowledge about the functioning of these lake-wetland systems. Pointing out the essential role of wetlands in the existence of water (especially lake) ecosystems, could limit or stop many negative actions. The authors of the paper hope that such ecologically valuable lake-wetland ecosystems will gain even greater value within our society.

References

Bałaga K (2003) Hydrological changes in the Lublin Polesie during the late glacial and Holocene as reflected in the sequences of lacustrine and mire sediments. Studia Quarternaria 19:37–53

Beckwith CW, Baird AJ, Heathwaite AL (2003) Anisotropy and depth-related heterogeneity of hydraulic conductivity in a bog peat. I: laboratory measurements. Hydrological Processes 17:89–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.1116

Cheng X, Anderson MP (1994) Simulating the influence of lake position on groundwater fluxes. Water Resources Research 30(7):2041–2049. https://doi.org/10.1029/93WR03510

Chmiel S (2009) Hydrochemical evaluation of dystrophy of the water bodies in the Łęczna and Włodawa area in the years 2000-2008. Limnological Review 9(4):157–162

Chmielewski TJ, Kułak A, Michalik-Śnieżek M (2014) Method of retrospective evaluation of physiognomic landscape changes and its application in the west Polesie region (CE Poland). Regional Environmental Change 14(4):1627–1639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0601-4

Choiński A (2007) Limnologia fizyczna Polski [physical limnology of Poland]. Wyd. Naukowe UAM, Poznań, pp 1–548

Cieśliński R, Piekarz J, Zieliński M (2016) Groundwater supply of lakes: the case of Lake Raduńskie Górne (northern Poland, Kashubian Lake District). Hydrological Sciences Journal 61(13):2427–2434

Dai TS, Sparling JH (1973) Measurement of hydraulic conductivity of peats. Canadian Journal of Soil Science 53(1):21–26

Dembek W, Oświt J (1992) Rozpoznanie warunków hydrologicznego zasilania siedlisk mokradłowych [identification of hydrological conditions for recharge of palustrine habitats]. Biblioteka Wiadomości IMUZ 79:15–38

Dobrowolski R (2006) Glacjalna i peryglacjalna transformacja rzeźby krasowej północnego przedpola wyżyn lubelsko-wołyńskich (Polska SE, Ukraina NW) [glacial and periglacial transformation of karst relief in the northern foreland of the Lublin Volhynia uplands (SE Poland, NW Ukraine)]. Wyd. UMCS, Lublin, 188 pp

Ferone JM, DeVito KJ (2004) Shallow groundwater–surface water interaction in pond-peatland complexes along a Boreal Plains topographic gradient. Journal of Hydrology 292:75–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2003.12.032

Fijałkowski D (1996) Ochrona przyrody i środowiska naturalnego w środkowowschodniej Polsce [Nature and natural environment protection in the central-eastern Poland]. Wyd. UMCS, Lublin, 1–318

Frei S, Lischeid G, Fleckenstein JH (2010) Effects of micro-topography on surface–subsurface exchange and runoff generation in a virtual riparian wetland-a modeling study. Advances in Water Resources 33(11):1388–1401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2010.07.006,2010

Gerla PJ (1999) Estimating the ground-water contribution in wetlands using modeling and digital terrain analysis. Wetlands 19(2):394–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03161771

Harasimiuk M, Dobrowolski R, Rodzik J (2002) Budowa geologiczna i rzeźba Poleskiego Parku Narodowego [Geological structure and relief of the Poleski National Park]. In: Radwan S (eds) Poleski Park Narodowy. Monografia przyrodnicza [Poleski National Park. Environmental monography]. Morpol, Lublin, 29–42

Hunt RJ, Haitjema HM, Krohelski JT, Feinstein DT (2003) Simulating ground water-Lake interactions: approaches and insights. Groundwater 41(2):227–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.2003.tb02586.x

Hunt RJ, Krohelski JT (1996) The application of an analytic element model to investigate groundwater-Lake interactions at pretty lake, Wisconsin. Lake and Reservoir Management 12(4):487–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/07438149609354289

Hunt RJ, Walker JF, Krabbenhoft DP (1999) Characterizing hydrology and the importance of ground-water discharge in natural and constructed wetlands. Wetlands 19(2):458–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03161777

Ilnicki P (2002) Torfowiska i torf [Peatlands and peat]. Wyd. AR, Poznań, 1–606

Iwanek M (2005) Badanie współczynnika filtracji gleb metodą polową i w laboratorium [analysis of hydraulic conductivity of soils by means of field and laboratory methods]. Acta Agrophysica 55(1):39–47

Iwanow KE (1953) Gidrologija bolot [Wetland hydrology] In: A. A. Sokolov (Eds.) Gidrometeorologitcheskoje Izdatelstvo. Gidrometeoizdat, Leningrad, 1–295

Jaros H (2006) Właściwości filtracyjne gleb i utworów hydrogenicznych oznaczane różnymi metodami [permeability properties of soils and hydrogenic sediments analyzed by means of various methods]. In: Brandyk T, Szajdak L, Szatyłowicz J. (Eds.) Właściwości fizyczne i chemiczne gleb organicznych [Physical and chemical properties of organic soils]. Wyd. SGGW, Warszawa, 127–140

Kellner E (2007) Effects of variations in hydraulic conductivity and flow conditions on groundwater flow and solute transport in peatlands, SKB, University of Helsinki, Finland http://www.iaea.org/inis/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/38/117/38117445.pdf, Accessed 3 Feb 2015

Krohelski JT, Rose WJ, Hunt RJ (2002) Hydrologic investigation of Powell Marsh and its relation to Dead Pike Lake, Vilas County, Wisconsin. Water-Resources Investigations Report No 02–4034, Middleton, Wisconsin, 1–20

Lange W (Ed.) (1993) Metody badań fizycznogeograficznych [methods of physical-geographical research]. Wyd. Uniw. Gdańskiego, Gdańsk, 1–175

Malinowska E, Hyb M (2004) Wyznaczanie współczynnika filtracji na podstawie badań laboratoryjnych [determination of hydraulic conductivity on the basis of laboratory research]. EU GeoEnvNet Seminar on Geoenvironmental Engineering–Transfer of Knowledge and EU's Directives to Newly Associated States, SGGW, Warszawa, 71–81

Malloy S (2013) Fen restoration on a bog cut down to sedge peat: a hydrological assessment of rewetting and the impact of a subsurface gyttja layer, University of Waterloo, https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/handle/10012/7355. Accessed 10 Jan 2016

Michalczyk Z (1998) Stosunki wodne Pojezierza Łęczyńsko-Włodawskiego [Water conditions of Łęczna-Włodawa Lake District]. In: Harasimiuk M, Michalczyk Z, Turczyński M. (Eds.) Jeziora Łęczyńsko-Włodawskie. Monografia przyrodnicza [Łęczna-Włodawa lakes. Environmental monography]. BMŚ, UMCS Lublin, PIOŚ Warszawa, 55–70

Ojiambo SB, Lyons WB, Welch KA, Poreda RJ, Johannesson KH (2003) Strontium isotopes and rare earth elements as tracers of groundwater–lake water interactions, Lake Naivasha, Kenya. Applied Geochemistry 18(11):1789–1805

Okruszko H (1976) Field methods for the peat decomposition degree determination in the three- and ten- grade scale. Transactions of the Working Group for Classification of peat. International PeatSociety Commission I. Helsinki: IPS, 27–30

Päivänen J (1973) Hydraulic conductivity and water retention in peat soils, Acta Forestalia Fennica.129:1–70. http://hdl.handle.net/1975/8450. Accessed 20 Feb 2016

Pazdro Z, Kozerski B (1990) Hydrogeologia ogólna [General hydrogeology]. Wyd. Geol., Warszawa, 1–623

Petrone RM, Devito KJ, Silins U, Mendoza C, Brown SC, Kaufman SC, Price JS (2008) Transient peat properties in two pond-peatland complexes in the sub-humid western boreal plain, Canada. Mires Peat 3(5):1–13 http://mires-and-peat.net. Accessed 18 Dec 2015

Rogoż M (2012) Metody obliczeniowe w hydrogeologii [Computable methods in hydrogeology]. Wyd. Naukowe “Śląsk”, Katowice, 1–530

Rosa E, Larocque M (2008) Investigating peat hydrological properties using field and laboratory methods: application to the Lanoraie peatland complex (southern Quebec, Canada). Hydrological Processes 22(12):1866–1875. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.6771

Rudnick S, Lewandowski J, Nützmann G (2015) Investigating groundwater-Lake interactions by hydraulic heads and a water balance. Groundwater 53(2):227–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.12208

Rycroft DW, Williams DJA, Ingram HAP (1975) The transmission of water through peat I. Review. Journal of Ecology 63:535–556. https://doi.org/10.2307/2258734

Rydelek P, Bąkowska A, Zawrzykraj P (2014) Variability of horizontal hydraulic conductivity of fen peats from eastern Poland in relation to function of peatlands as a natural geological barriers. Geological Quarterly 59(1):426–432

Sacks LA, Herman JS, Konikow LF, Vela AL (1992) Seasonal dynamics of groundwater-lake interactions at Donana National Park, Spain. Journal of Hydrology 136:123–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(92)90008-J

Shaw RD, Prepas EE (1990) Groundwater-lake interactions: II. Nearshore seepage patterns and the contribution of ground water to lakes in Central Alberta. Journal of Hydrology 119:121–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(90)90038-Y

Smerdon BD, Devito KJ, Mendoza CA (2005) Interaction of groundwater and shallow lakes on outwash sediments in the sub-humid Boreal Plains of Canada. Journal of Hydrology 314:246–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.04.001

Stets EG, Winter TC, Rosenberry DO, Striegl RG (2010) Quantification of surface water and groundwater flows to open and closed-basin lakes in a headwaters watershed using a descriptive oxygen stable isotope model. Water Resources Research 46(3). https://doi.org/10.1029/2009WR007793

Sugier P (1998) Przekształcenia szaty roślinnej Jeziora Czarnego Gościnieckiego na Pojezierzu Łęczyńsko-Włodawskim [Changes of plants in Czarne Gościnieckie Lake in Łęczna-Włodawa Lake District]. Przegląd Przyrodniczy 9(1/2):213–222

Thompson C, Mendoza CA, Devito KJ, Petrone RM (2015) Climatic controls on groundwater-surface water interactions within the Boreal Plains of Alberta: field observations and numerical simulations. Journal of Hydrology 527:734–746

Tiner R (1999) Wetland indicators: a guide to wetland identification, delineation, classification, and mapping. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, CRC Press, London, New York, Washington, 1–392

Townley LR, Trefry MG (2000) Surface water–groundwater interaction near shallow circular lakes: flow geometry in three dimensions. Water Resources Research 36(4):935–948. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999WR900304

Troels-Smith J (1955) Karakteriserung af lose jordarter. Characterization of unconsolidated sediments. Geological Survey of Denmark, Series IV 3(10):1–73

Turczyński M, Sobolewski W, Mięsiak-Wójcik K (2009) Selected problems related to the demarcation of lake range in the light of field surveys. Limnological Review 9(4):3–12

van der Schaaf S (2004) A single well pumping and recovery test to measure in situ acrotelm transmissivity in raised bogs. Journal of Hydrology 290(1):152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2003.12.005

Walker JF, Krabbenhoft DP (1998) Groundwater and surface-water interactions in riparian and lake-dominated systems. Isotope tracers in catchment. Hydrology:467–488

Winter TC (1999) Relation of streams, lakes, and wetlands to groundwater flow systems. Hydrogeology Journal 7(1):28–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100400050178

Wojciechowski KH (1991) Warunki obiegu wody w zlewniach jezior Piaseczno i Głębokie [Conditions of water circulation in catchments of Piaseczno and Głębokie lakes]. Studia Ośrodka Dokumentacji Fizjograficznej, PAN Oddział w Krakowie 19:175–192

Zawadzki S, Olszta W (1977) Wpływ stopnia rozkładu, głębokości zalegania oraz rodzaju torfu na wielkość przepuszczalności organicznych utworów glebowych [Effect of degree of decomposition, depth of occurrence and type of peat on hydraulic conductivity of organic soil sediments]. Materiały Seminaryjne, Falenty 11:71–79

Żurek S (2010) Metody badań osadów bagiennych [Paludal sediments and their methods of investigation]. Landform Analysis 12:137–148

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported from the funds of Polish Ministry of Sciences and High Education in the framework of grant No. 1803/B/PO1/2009/37: Importance of transitional retention zones in water inflow to lakes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mięsiak-Wójcik, K., Turczyński, M. & Sposób, J. Diverse Sediment Permeability and Implications for Groundwater Exchange in Closed Lake-Wetland Catchments (West Polesie, East Poland). Wetlands 38, 779–792 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-018-1027-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-018-1027-4