Abstract

An occupied niche space implies resource use, and understanding the factors that lead to change in trophic niches is vital to assess food web structures. Quantifying niches and niche overlaps are important to assess interspecies resource partitioning and competition. In this study, stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes were used to characterize trophic niche width of and niche overlap among three commercially-important benthic-living fish (Carassius auratus, Pelteobagrus fulvidraco, and Silurus asotus) collected from northern and southern Poyang Lake. The separation of snails and mussels on the δ13C at southern part indicating the integration of terrestrial derived organic carbon, which led to larger trophic niche widths of fish in the south. The δ15N ratios of fishes were significantly higher in the northern Lake than in the southern part. Furthermore, the trophic overlaps were higher in the south than in the north. Trophic niche width of C. auratus was the smallest as their food sources were easy to acquire, and consumers tended to specialize and narrow their trophic niches when food resource is abundant. S. asotus, a predator species, was short of animal food sources due to heavy fishing pressure. Therefore, its diet broadened, and the trophic niche width was the largest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hutchinson’s conceptualization of niche as an n-dimensional hypervolume is a crucial foundation for ecologists (Hutchinson 1957). An occupied niche space implies resource use, and understanding the factors that lead to change in trophic niches is important to assess food web structures, resource use, and trophic interactions. Assessing the functional role of a specie depends on quantifying its trophic niche width, which represents the richness and evenness of resources consumed (Bearhop et al. 2004). When resources are limited, coexisting species may overlap along many niche axes but must differ in at least one to avoid competitive exclusion (Hutchinson 1957).

Quantifying niches and species niche overlaps is of interest to many ecologists. Recent advances in stable isotope ecology have proven that carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes are powerful tools in this area (Bearhop et al. 2004; Newsome et al. 2007). The isotopic signature of carbon (δ13C) provides information on the food source of the consumer, and the isotopic signature of nitrogen (δ15N) is associated with the trophic level (Peterson and Fry 1987). Isotopic variation within a consumer population can be utilized to examine niche characteristics through space and time because the isotopic composition of consumer tissues predictably reflects assimilated diet (Bearhop et al.2004; SyvÄRanta and Jones 2008). For example, Xu et al. (2012) found that Yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) could adjust their foraging strategies to temporal changes in food availability in Taihu Lake. In summer, they tend to forage small fish and shrimp to balance the energy demand on growth and reproduction. A study on two coexisting planktivores (silver carp and bighead carp) in southern China revealed a trophic niche overlap between these two species in an oligotrophic system with limited resources, and a hypereutrophic system with high resource availability. No such overlap was found in mesotrophic systems as moderate watershed size and productivity allowed bighead carps to exploitatively consume zooplankton, which made silver carp shift to phytoplankton (Chen et al. 2011). Advances in mathematical techniques have made quantifying niche dimensionality among and within communities increasingly practicable (Layman et al. 2007; Jackson et al. 2011; Swanson et al. 2015). For example, a study on native and invasive fish demonstrated that narrow trophic niche areas and high overlaps with non-native species are the reasons for the decline of native species populations in Lake Patzcuaro, Mexico (Cordova-Tapia et al. 2015).

Poyang lake is a complex wetland system with the composition of water, sand, mudflat and numerous species of vegetation (Han et al. 2015). The inundation regimes and water level fluctuations are largely controlled by the dynamic balance of five major tributaries (Gan River, Fu River, Xin River, Rao River, Xiu River) and the Yangtze River. Seasonal water level fluctuation determines vegetation cover area (Wang et al. 2011, 2012; You et al. 2015) which are important spawning, feeding, and roosting habitats for fishes. Fishery in Poyang Lake provides an important source of income and protein to local people. The average annual capture of wild stocks of freshwater fish from 2000 to 2011 was 3.1 × 104 t (Jiang et al. 2013). Around 137 species of fish exist in Poyang Lake, including 53 benthic species (38.7%) (Zeng 2014). Carassius auratus, Pelteobagrus fulvidraco, and Silurus asotus are important commercial fishes because they are widely distributed, adapt to water regime and hace large yield. These three species account for 35% of the total fishery catch (Jiang et al. 2013). S. asotus is carnivorous. P. fulvidraco and C. auratus are omnivorous, but P. fulvidraco favors animal food and C. auratus favors plant food (Zhang et al. 2013). The main food sources for C. auratus are plant materials, zooplankton, and benthic invertebrates (Zhang 2005). P. fulvidraco consume small fish, shrimps, mussels, snails, and aquatic insects (Tan 1997). S. asotus consume fish, shrimps, crabs, and snails (Yang et al. 2002).

Studies have found that diet composition of wetland fishes varied between hydrological periods (Silva et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2011, 2012). Flow reductions in wetland systems could increase the dietary overlap between fishes (Mazumder et al. 2012). Potential food source for fishes in Poyang Lake also varied as wetland water level fluctuated (Wang et al. 2011, 2012), however it is not clear about trophic relationship during high water seasons. Although many studies have found spatial variations in water environments and nutrient concentrations in Poyang Lake (Hu et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2013a, b, c; Liu et al., 2016), only a few studies (Wang et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2015) have focused on whether these spatial variations influence fish niches and trophic relationships in this large and complex floodplain lake. The primary objective of this study is to determine the niche space and dietary overlap among three benthic species of fish residing northern and southern parts of Poyang Lake experiencing heavy fishing pressure during high water seasons.

Materials and methods

Sampling and pretreatment

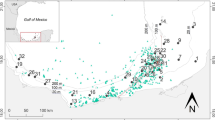

Samples of fish and macrozoobenthos were collected on August 2011 in the northern and southern parts of Poyang Lake (Fig. 1) when the water level was high. The northern narrow part from lake outlet to Xingzi county is Hukou segment, the southern open water area belongs to Poyang Lake fault depression. C. auratus, P. fulvidraco, and S. asotus were collected at two sites by local fishermen in each part of the lake. The fish were preserved in ice, and their white dorsal muscle tissues were dissected in the laboratory.

Mussels and snails used in stable isotope analysis were collected by 0.05 m2 modified Peterson grab at the location where fish nets were settled. At each site, 10 Peterson grab samples were taken to survey biomass and abundance of macrozoobenthos. The grab samples were pre-sieved in situ through a 250 μm (mesh size) sieve before being taken to the laboratory for further sorting. In the laboratory, samples were sorted on a white tray, counted, blotted dry, and weighted to determine their wet weight through an electronic balance. Foot muscle tissues of two dominant species Corbicula fluminea and Bellamya aeruginosa with wet weight more than 2.0 g were cut by scalpel. The tissues of animals were dried at 60 °C to a constant weight. These samples were then ground to fine homogeneous powder with mortar and pestle and placed in tin capsules for stable isotope analysis.

At the 20 grab sampling sites, water samples were also collected. Water depth and Secchi depth were measured in the field. Turbidity was measured with a Hydrolab DataSonde 5 (HydroLab Corporation, Austin, Texas, USA) sensor in situ. Water samples were collected and placed in acid-cleaned 10 L plastic containers and kept cool and shaded before transportation to the laboratory. Total nitrogen (TN), ammonium (NH4-N), nitrate (NO3-N), suspended solids (SS), chemical oxygen demand (CODMn), and chlorophyll a (Chl-a) were measured in the laboratory according to American Public Health Association (APHA) standards (2012).

Stable isotope analysis

Stable isotopic analysis was performed with Finnegan MAT 253 (Thermo Scientific, USA) continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer coupled with a Flash Elemental Analyzer 1112 system (Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences). The isotope ratios were expressed as δ13C and δ15N (per thousand percent) with the following equation: δX = [(Rsample/Rstandard) − 1] × 1000, where X is 13C or 15N and R is the corresponding ratio of 13C/12C or 15N/14N. The reference standard for δ13C was Pee Dee Belemnite limestone and atmospheric nitrogen for δ15N. Based on replicates of laboratory standards (urea), the observed analytical precisions of δ13C and δ15N were ±0.1% and ±0.3%, respectively. Due to low lipid content (C:N of all fish samples <3.5), lipid content for muscle tissues was normalized (Post et al. 2007).

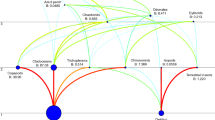

Standard ellipse areas (SEA) (Syväranta et al. 2013) in the δ13C–δ15N bi-plots of each fish were utilized to compare the isotopic niches. SEA was estimated with multivariate ellipse-based metrics, which are bivariate equivalents of SDs in univariate analysis and contain 40% of the data regardless of the sample size; therefore, they represent the core dietary niche and reveal the typical resource use within a species or population (Jackson et al. 2011). We calculated the isotopic niche occupied by each fish by using the SIAR package in the R computing program (Jackson et al. 2011; R Development Core Team 2015). When the SEAs overlapped, we also calculated the area and percentage of overlap through the Monte Carlo method to bootstrap the same number of samples for each fish. The procedure was repeated 1000 times for each species, and the mean of each value of the trophic niche analysis and the trophic niche overlap were calculated. We calculated the isotopic niche overlap of fishes with the nicheROVER package in the R computing program (R Development Core Team 2015; Swanson et al.2015).

Nonparametric one way ANOVA was used to determine macrozoobenthos biomass, macrozoobenthos abundance, water quality difference and isotopic variability in B. aeruginosa, C. fluminea, C. auratus, S. asotus, P. fulvidraco between northern and southern parts of Poyang Lake.

Results

Sample sizes, length range and mean length for the fishes used in the isotope analysis are shown in Table 1. The difference between body length of fishes collected at northern and southern parts was not significant (Table 1, all p > 0.05).

Grazing snail, B. aeruginosa, and filter-feeding mussel, C. fluminea presented in 80.0% and 63.6% of sampled sites at northern and southern Poyang Lake. These two species accounted for 67.3% and 76.5% of the biomass of macrozoobenthos in northern and southern part, respectively. Although the biomass and abundance of total macrozoobenthos were lower in the northern part than in the southern part, the difference were insignificant (Table 2, all p > 0.05). Only NH4-N concentration in water was significantly lower (p = 0.001) in the northern part than in the southern part (Table 2), while other physical and chemical variables of the water environment during high water times showed no significant difference.

The δ13C and δ15N values of both mussel and snail varied significantly between northern and southern parts of the lake (Table 3). The δ15N values of three fish species were significantly different between locations (Table 3). The enriched δ15N value indicated that S. asotus was higher in the food chain in Poyang Lake (Fig. 2). The trophic niche widths of C. auratus, P. fulvidraco, and S. asotus were 24.7% smaller in northern than in southern Poyang Lake (Fig. 3, Table 4). Assessment of the isotopic niche overlap showed that the probability that C. auratus fed within the dietary niche of the P. fulvidraco population was up to 90.09% in southern Poyang Lake, and the probability that P. fulvidraco fed from within the dietary niche of C. auratus was 73.39% (Table 5). The lowest isotopic niche overlap was 23.54% found between S. asotus and C. auratus in Northern Poyang Lake (Table 5). Niche overlaps among these three fish species were higher in southern part (Table 5).

Discussion

Water flow is high in northern Poyang Lake (Gu and Wan 2011). The high flow might lead to dilution of nutrients in the water and slightly reduces the concentration of nutrients (i.e., TN, NO3-N, and NH4-N). Chen et al. (2013c) also reported that TN concentration in the water samples of Poyang Lake had a downward trend from the south part to the north part. Meanwhile, suspended solids and turbidity are also higher at southern part.

In the northern part, mussels and snails overlapped on their δ13C values but not on their δ15N values, while the opposite was observed in the southern area. The separation of snails and mussels on the δ13C in the southern area implied different basal resource inputs feeding the food web (Rossi et al. 2010). In the southern large open water area C. fluminea has more negative δ13C values, indicating the integration of terrestrial derived organic carbon from surrounding wetlands, while the higher δ13C values of B. aeruginosa indicating the assimilation of aquatic derived organic carbon. Both Wang et al. (2011) and Zhang et al. (2017) had reported contribution of terrestrial plants to consumers in Poyang Lake food web. S. asotus had the highest δ15N ratio, and C. auratus had the lowest δ15N ratio. These results confirmed the previous trophic position estimations according to records of dietary analysis (Tan 1997; Yang et al.2002; Zhang 2005). Wang et al. (2014a) found that the δ15N value of suspended particulate organic matter in Xingzi could reach 19.69‰ at high water seasons because of large amounts of domestic sewage discharge and pollution from livestock breeding. Agricultural non-point source pollution and soil erosion in the basin have caused the δ15N value of sediments in Duchang to be the highest (6.72‰) (Wang et al. 2014b). Marcozoobenthos consumes suspended particulate organic matter and surface sediment organic matter, δ15N value of their muscle enriched due to their food sources have high δ15N ratios (Wang et al. 2014a, b). Since trophic baselines in the northern part are already enriched with δ15N; thus, consumers, such as fish, in the food web are also enriched with δ15N (Wang et al. 2009).

The range of the variance of δ13C signatures of baseline species was wider in the southern part. The SEAs of C. auratus, P. fulvidraco and S. asotus were also larger in southern than in north part (Figs. 2 and 3), reflected the δ13C range width of baseline species (Sanders et al. 2015).

Plants were relatively easy to acquire since Poyang Lake was rich in vegetation (You et al. 2015), SEA of C. auratus was smallest among these benthic fishes as consumers tended to specialize and narrow their trophic niches when high resource availability presence (Rossi et al. 2015). Due to heavy fishing pressure in Poyang Lake (Wang et al. 2014), even small fish were capture by local fish men, the predator S. asotus might be short of food sources. As a result, its diet was broadened, and had the largest trophic niche width (SEA) in both northern and southern parts (Table 4).

Trophic overlaps indicate shared diets. In Lake Poyang, the three commercially-important benthic-living fish species displayed substantial trophic niche overlaps, suggesting that they consume the same food source of aquatic macrozoobenthos. Optimal foraging theories predict trophic niche broadening as a consequence of reduced food availability, where consumers relying on insufficient preferred food items are forced to add less profitable resources to their diet, hence widening their trophic niche (Rossi et al., 2015; Calizza et al. 2017). For example, in the southern part of the lake, overlapping between S. asotus and C. auratus, S. asotus and P. fulvidraco were higher than in northern part (Table 5), implied higher intraspecific competition, which would promote trophic generalization within populations due to differentiation in food use among conspecifics (Svanback and Bolnick 2007), led to increase of S. asotus trophic niche width.

References

APHA (2012) Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater 22 ed. American Public Health Association, Washington, DC

Bearhop S, Adams CE, Waldron S, Fuller RA, Macleod H (2004) Determining trophic niche width: a novel approach using stable isotope analysis. The Journal of Animal Ecology 73:1007–1012

Calizza E, Costantini ML, Careddu G, Rossi (2017) Effect of habitat degradation on competition, carrying capacity, and species assemblage stability. Ecology and Evolution 7:5784–5796

Chen G, Wu ZH, Gu BH, Liu DY, Li X, Wang Y (2011) Isotopic niche overlap of two planktivorous fish in southern China. Limnology 12:151–155

Chen GJ, Hou WB, Li MT, Tong L, Hu CH (2013a) Research on the of nitrogen and phosphorus on the phytoplankton community in Poyang Lake. China Rural Water Hydropower 3:48–52+61

Chen GJ, Zhou WB, Hu CH (2013b) Assessment of phytoplanktonic diversity and present nutrition status in the five river estuaries of Poyang Lake. Hubei Agricultural Sciences 54:2048–2052

Chen XL, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Chen LQ, Lu JZ (2013c) Distribution characteristic of nitrogen and phosphorus in lake Poyang during high water period. Journal of Lake Science 25:643–648

Cordova-Tapia F, Contreras M, Zambrano L (2015) Trophic niche overlap between native and non-native fishes. Hydrobiologia 746:291–301

Gu P, Wan JB (2011) Hydrology character of Poyang Lake and its influence on water quality. Environmental Pollution & Control 3:15–19

Han X, Chen X, Feng L (2015) Four decades of winter wetland changes in Poyang Lake based on Landsat observations between 1973 and 2013. Remote Sensing of Environment 156:426–437

Hu CH, Zhou WB, Wang ML, Wei ZW (2010) Inorganic nitrogen and phosphate and potential eutrophication assessment in Lake Poyang. Journal of Lake Science 22:723–728

Hutchinson GE (1957) Concluding remarks. Population studies: animal ecology and demography. Cold Spring Harbour Press, New York, pp 415–427

Jackson AL, Inger R, Parnell AC, Bearhop S (2011) Comparing isotopic niche widths among and within communities: SIBER - Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R. The Journal of Animal Ecology 80:595–602

Jiang H, Liu LT, Zheng XS (2013) The Poyang Lake fishery resources environment status and protection countermeasures. Fishery Modernization 40:68–72

Layman CA, Arrington DA, Montana CG, Post DM (2007) Can stable isotope ratios provide for community-wide measures of trophic structure? Ecology 88:42–48

Liu X, Li YA, Liu BG, Qian KM, Chen YW, Gao JF (2016) Cyanobacteria in the complex river-connected Poyang Lake: horizontal distribution and transport. Hydrobiologia 768:95–110

Mazumder D, Johansen M, Saintilan N, Iles J, Kobayashi T, Knowles L, Wen L (2012) Trophic shifts involving native and exotic fish during hydrologic recession in floodplain wetlands. Wetlands 32:267–275

Newsome SD, del Rio CM, Bearhop S, Phillips DL (2007) A niche for isotopic ecology. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 5:429–436

Peterson BJ, Fry B (1987) Stable isotopes in ecosystem studies. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 18:293–320

Post DM, Layman CA, Arrington DA, Takimoto G, Quattrochi J, Montana CG (2007) Getting to the fat of the matter: models, methods and assumptions for dealing with lipids in stable isotope analyses. Oecologia 152:179–189

R Development Core Team (2015) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Rossi L, Costantini ML, Carlino P, di Lascio A, Rossi D (2010) Autochthonous and allochthonous plant contributions to coastal benthic detritus deposits: a dual-stable isotope study in a volcanic lake. Aquatic Sciences 72:227–236

Rossi L, di Lascio A, Carlino P, Calizza E, Costantini ML (2015) Predator and detritivore niche width helps to explain biocomplexity of experimental detritus-based food webs in four aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecological Complexity 23:14–24

Sanders D, Vogel E, Knop E (2015) Individual and species-specific traits explain niche size and functional role in spiders as generalist predators. The Journal of Animal Ecology 84:134–142

Silva JCD, Éder André Gubiani, Neves MP, Delariva RL (2017) Coexisting small fish species in lotic neotropical environments: evidence of trophic niche differentiation. Aquatic Ecology 51:1–14

Svanback R, Bolnick DI (2007) Intraspecific competition drives increased resource use diversity within a natural population. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 274:839–844

Swanson HK, Lysy M, Power M, Stasko AD, Johnson JD, Reist JD (2015) A new probabilistic method for quantifying n-dimensional ecological niches and niche overlap. Ecology 96:318–324

SyvÄRanta J, Jones RI (2008) Changes in feeding niche widths of perch and roach following biomanipulation, revealed by stable isotope analysis. Freshwater Biology 53:425–434

Syväranta J, Lensu A, Marjomäki TJ, Oksanen S, Jones RI (2013) An empirical evaluation of the utility of convex hull and standard ellipse areas for assessing population niche widths from stable isotope data. PLoS ONE 8:e56094

Tan BP (1997) Analyses on ecological importance of several carnivorous fishes in Lake Taihu. Reservoir Fisheries 5:27–30

Wang YY, Yu XB, Zhang L, Xu J (2009) Food web structure of Poyang Lake during the dry season by stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes analysis. Acta Ecologica Sinica 29:1181–1188

Wang YY, Yu XB, Li WH, Xu J, Chen YW, Fan N (2011) Potential influence of water level changes on energy flows in a lake food web. Chinese Science Bulletin 56:2794–2802

Wang YY, Yu XB, Xu J, Li WH, Fan N (2012) Temporal variation of energy sources in a floodplain lake fish community. Journal of Freshwater Ecology 27:295–303

Wang Y, Xu J, Yu X, Lei G (2014) Fishing down or fishing up in Chinese freshwater lakes. Fisheries Management and Ecology 21:374–382

Wang ML, Zhang DL, Lai JP, Hu KT, Lai JH (2014a) Distribution and sources of stable organic carbon and nitrogen isotopes in suspended particulate organic matter of Poyang Lake. China Environmental Science 4:2342–2350

Wang ML, Lai JP, Hu KT, Zhang DL, Lai JH (2014b) Compositions and sources of stable organic carbon and nitrogen isotopes in surface sediments of Poyang Lake. China Environmental Science 34:1019–1025

Wu Z, Cai Y, Liu X, Xu CP, Chen Y, Zhang L (2013) Temporal and spatial variability of phytoplankton in Lake Poyang: the largest freshwater lake in China. Journal of Great Lakes Research 39:476–483

Xu J, Wen ZR, Gong ZJ, Zhang M, Xie P, Hansson LA (2012) Seasonal trophic niche shift and cascading effect of a generalist predator fish. PLoS ONE 7:e49691

Yang RB, Xie CX, Yang XF (2002) Study on the diet content of six species of fierce fish in Lake Liangzi. Reserve Fish 22:1–3

Yang SR, Li MZ, Zhu QG, Wang MR, Liu HZ (2015) Spatial and temporal variations of fish assemblages in Poyanghu Lake. Resources and Environment in Yangtze Basin 24:54–64

You H, Xu L, Liu G, Wang X, Wu Y, Jiang J (2015) Effects of inter-annual water level fluctuations on vegetation evolution in typical wetlands of Poyang Lake, China. Wetlands 35:931–943

Zeng ZG (2014) Studies on diversity, age and growth of fishes in sublakes of Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve, Jiangxi China. Master dissertation, Nanchang University

Zhang TL (2005) History strategies, trophic patterns and community structure in the fishes of Lake Biandantang. PhD dissertation, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Zhang H, Zhang H, Wu G, Zhang P, Xu J (2013) Trophic fingerprint of fish communities in subtropical floodplain lakes. Ecology of Freshwater Fish 22:246–256

Zhang H, Yu X, Wang Y, Xu J (2017) The importance of terrestrial carbon in supporting molluscs in the wetlands of Poyang Lake. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology 35:825–832

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41301077). We would like to thank Dr. Li Wen and Prof. Jun Xu for their comments on the early version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Huan, Z., YuWei, C. et al. Trophic Niche Width and Overlap of Three Benthic Living Fish Species in Poyang Lake: a Stable Isotope Approach. Wetlands 39 (Suppl 1), 17–23 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-018-0995-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-018-0995-8