Abstract

Purpose of the review

Non-invasiveness and instantaneous diagnostic capability are prominent features of the use of echocardiography in critical care. Sepsis and septic shock represent complex situations where early hemodynamic assessment and support are among the keys to therapeutic success. In this review, we discuss the range of applications of echocardiography in the management of the septic patient, and propose an echocardiography-based goal-oriented hemodynamic approach to septic shock.

Recent findings

Echocardiography can play a key role in the critical septic patient management, by excluding cardiac causes for sepsis, and mostly by guiding hemodynamic management of those patients in whom sepsis reaches such a severity to jeopardize cardiovascular function. In recent years, there have been both increasing evidence and diffusion of the use of echocardiography as monitoring tool in the patients with hemodynamic compromise. Also thanks to echocardiography, the features of the well-known sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction have been better characterized. Furthermore, many of the recent echocardiographic indices of volume responsiveness have been validated in populations of septic shock patients.

Conclusion

Although not proven yet in terms of patient outcome, echocardiography can be regarded as an ideal monitoring tool in the septic patient, as it allows (a) first line differential diagnosis of shock and early recognition of sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction; (b) detection of pre-existing cardiac pathology, that yields precious information in septic shock management; (c) comprehensive hemodynamic monitoring through a systematic approach based on repeated bedside assessment; (d) integration with other monitoring devices; and (e) screening for cardiac source of sepsis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Rationale for the use of echocardiography in the septic critical patient

Sepsis and septic shock (SS) are common causes of cardiovascular failure in critical care and are the most frequent causes of mortality in intensive care units [1, 2]. SS is one of the most complex hemodynamic failure syndromes, as it may imply derangement of all the three mainstays of cardiovascular homeostasis, each one to a variable degree: absolute or relative reduction in central blood volume, peripheral vasodilatation and myocardial failure may coexist and variably overlap in different phases of septic shock’s course [3, 4]. Echocardiography (ECHO) has nowadays acknowledged clear indications in hemodynamic instability [5], is increasingly used by intensive and critical care physicians, and is advocated by many as an irreplaceable tool in the approach to and management of the critical patient [6–8]. Many are the reasons that make ECHO suitable for guiding hemodynamic management of septic critical patients at different stages of their critical illness: (1) non-invasiveness, rapidity—in adequately trained hands ECHO has the potential to non-invasively provide at the bedside instantaneous relevant diagnostic information on patients’ cardiovascular status [9, 10]. Even though a comprehensive ECHO examination may be time consuming, time required for a focused, limited ECHO examination ranges from seconds to a dozen of minutes [11, 12]; (2) diagnostic yield, monitoring capabilities—ECHO offers the matchless advantage to perform both detailed functional and morphological assessment of the heart; pathological changes in venous return and vascular tone can then be assessed with dynamic investigation of their consequences on the heart and the great vessels [13–15]; (3) impact on patient management—even in patients already monitored invasively, both transthoracic ECHO (TTE) and transesophageal ECHO (TEE) add new relevant information that leads to changes in therapy in more than 50% of cases [12, 16, 17], the majority of which concern volume status and inotropy [17]; (4) flexibility—its use is scalable from a limited/focused to a comprehensive examination, according to time available and complexity of clinical queries. Either TTE or TEE can alternatively be used, according to availability and to the specific information needed; (5) accuracy—the use of ECHO as hemodynamic monitoring tool has already been validated in populations of septic shock patients [14], so as have been many of the most recent ECHO indices of volume responsiveness [18]. ECHO seems to be more accurate than the standardized strategy proposed by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines in the detection of the dominant features of the failing circulation [19]. Indeed, a simplified qualitative approach has demonstrated to be accurate enough [20]; (6) specific cardiac issues related to sepsis—the heart, main target of the ECHO examination, frequently represents itself the core of the septic process, being either “a victim” (when sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction develops) or its source (in the context of endocarditis).

The purpose of this review was to describe ECHO applications and potential findings in the critical septic patient, and provide a framework for the practical approach with Echo to SS management, both at onset and in the subsequent course of the disease.

Early management of the septic shock patient: focused echocardiography

Sepsis mortality is directly linked to hemodynamic instability resulting in tissue hypoxia, and prompt support aimed at specific hemodynamic targets has been demonstrated to reduce it significantly [21], up to saving the lives of one in six sepsis patient [22]. One key component of early goal-directed therapy strategies in SS is the accurate hemodynamic assessment and recognition of the dominant feature of the failing cardiovascular system (defective volume or vascular tone, failing heart pump) with subsequent appropriate management [23, 24]. Consistently with this need to accelerate the correct treatment, bedside TTE in the early phase of undifferentiated shock sharply reduces the number of viable diagnosis [25]. Focused ECHO findings typical of early SS (Table 1) are represented by signs of profound hypovolemia: ventricular hyperkinesia [small hypercontractile left ventricle, LV, with end-systolic obliteration of cavity [26] (Fig. 1a–c, Video 1A, B ESM), small hypercontractile right ventricle, RV] and small inferior vena cava with marked respiratory variations [27, 28] (Figs. 1e, f, 2a). Once this hemodynamic pattern has been detected, matched with clinical findings to make a presumptive diagnosis, and hemodynamic support started, an increase in inferior vena cava size [27] and in right and left ventricular end-diastolic dimensions [29] is expected with progression of volume resuscitation (Fig. 2b, c, Video 1 ESM). Persistent small end-systolic dimensions suggest then vasodilatation and need for vasoconstrictors upward titration. Furthermore, early performance of focused echo allows for timely screening of sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction and hence more careful fluid administration and early inotropic support (vide infra).

Septic shock at its onset, in hospital-acquired pneumonia, 3rd postoperative month of double lung transplant. Patient intubated and mechanically ventilated. SAP 85/40 mmHg, HR 160 bpm, with signs of inadequate tissue perfusion. TTE subcostal 4-chamber view (upper panels, Video 1A ESM) and parasternal short axis midpapillary view (middle panels, Video 1B ESM) show a hyperkinetic pattern, with marked reduction of LV and RV size from end-diastole (a, c) to end-systole (b, d). Inferior vena cava (subcostal IVC view, lower panels) is small (e) and shows significant increase in size with mechanical passive inspiration (f). RA right atrium, RV right ventricle, LA left atrium, LV left ventricle, IVC inferior vena cava

Early septic shock in central venous line-related bloodstream infection. Spontaneously breathing patient. Severe hypotension. Very small IVC end-expiratory diameter (aright side) and marked inspiratory collapse (a, M-mode scanning, left side) are in favor of severe hypovolemia. Subsequent volume loading (colloids 1,000 ml, crystalloids 300 ml), improves SAP. This is paralleled by a progressive increase in IVC end-expiratory size (b, c, red double-headed arrows). IVC inferior vena cava, RA right atrium, INSP inspiratory phase of respiratory cycle, SAP systemic arterial pressure, HR heart rate

SS superimposing on pre-existing cardiac dysfunction, or sepsis-triggered cardiac derangements (myocardial ischemia), or aggressive mechanical ventilation (hindering RV function in the context of ARDS, pneumonia) may determine from the beginning a different pattern, where typical features are missing, and RV or LV dysfunction appears as the main finding. Recognition of a relevant dilatation of any cardiac chamber other than the RV (the only chamber that can dilate acutely) or dilatation and hypertrophy of the RV gives clues toward a subjacent chronic dysfunction, avoids misdiagnosis of a primary cardiogenic aetiology of shock [15], and bears prognostic information linked to relevant co-morbidity. Severe LV hypertrophy and/or LV diastolic dysfunction may represent potential pitfalls on ventricular size-based volume status assessment: in this case, persistent LV small dimension does not equate to safe fluid infusion. Fluid administration should altogether not be gauged on LV or RV dimensions in the aforementioned settings of co-existing chronic heart disease, but rather on inferior vena cava size, when small, and on volume-responsiveness indices (vide infra).

Additional focused ultrasound investigations (lung, abdominal, soft tissues, beyond the scope of this review) in a multi-focused transversal approach [30, 31] should help in confirming suspicion of a septic etiology of the critical state and save time in early institution of empirical antibiotic therapy, upon appropriate bacteriological sampling.

Monitoring the patient with septic shock: comprehensive echocardiography

While pattern recognition may suffice in the very early approach to SS [32], with ongoing resuscitation or more complex situations (ex. co-existing disease), a systematic step-by-step assessment is necessary to monitor hemodynamics. Repeated bedside assessment at each hemodynamic deterioration or significant therapeutic variation is the key to the use of Echo in this hemodynamic fashion [14] and allows for prompt recognition and correction of the specific causes of cardiovascular instability, which is mandatory in SS management [20, 24, 33]. ECHO findings should be appropriately interpreted in the clinical context and integrated with available data from other monitoring tools (systemic arterial mean pressure, central venous pressure and saturation, arterial blood lactates, urine output), especially with the ones concerning the adequacy of tissue perfusion, on which echocardiography is blind. TEE always enables a complete assessment, inclusive of detailed heart–lung interactions and fine volume responsiveness evaluation, cardiac output assessment, and left-ventricular end-diastolic pressures estimation, when required. When adequate views can be achieved, TTE allows for even less invasive and thus more repeatable assessment, especially once key hemodynamic features have already been focused. ECHO reporting and storage of images and video clips allow for accurate comparison of findings obtained at different time spots and should thus be mandatory.

ECHO assessment should systematically seek for the following situations (Table 2), with the aim to guide fluid therapy and inotropic/vasoconstrictor support institution and titration:

Low output state

Stroke volume is calculated through Doppler sampling of LV outflow tract (LVOT) flows (TTE 5 chamber view or TEE deep TG/TG LAX view), and is feasible provided the absence of aortic valve pathology [34]. Doppler sampling provides the time–velocity integral of blood exiting the LV; this integral (a distance) is then multiplied by the calculated cross sectional area of the LVOT itself (TTE parasternal LAX view/ME LAX view), yielding a volume, the stroke volume and then turned into cardiac index (Fig. 3a, b). This method actually provides an estimation of cardiac index rather than a precise determination: most validation studies using thermodilution as gold standard for cardiac output measurement reported limits of agreement with TEE reaching ± 1 L/min [35]. In practice, ECHO is used to semi-quantify cardiac index (i.e. to allocate patients into ranges of values: very low/low/normal/high), and most usefully to evaluate variations following therapeutic maneuvres (Fig. 3c). Relying upon the LVOT velocity–time integral, rather than calculated stroke volume, eliminates the major source of error (i.e. LVOT cross-sectional area calculation). Furthermore, the issue of potential inaccuracy of thermodilution should not be overlooked [36]. Due to peripheral flow distributive derangements, usual normal values of CI should not be considered necessarily adequate in SS. Other ways to calculate the stroke volume include the 2D-based modified Simpson’s rule and the M-mode-based Teicholz method; even if easier in their approach, they are not sufficiently accurate to be recommended as routine practice.

TEE Doppler assessment of cardiac output in a community-acquired pneumonia patient with septic shock (same patient of Fig. 5). Patient is hypotensive and badly perfused and 2D images show a pattern of biventricular dysfunction. LVOT diameter is measured in a mid-esophageal long axis view (a, red double-headed arrow) and LVOT cross sectional area calculated (LVOT diameter = 2.23 cm; CSA = 1.115 cm × 1.115 cm × 3.14 = 3.90 cm2). Measured LVOT VTI (panel 3B, TEE transgastric long axis view) is 8.7 cm, calculated stroke volume is 34 ml (3.90 cm2 × 8.7 cm), and heart rate 104 bpm, yielding a CO of 3.55 L/min. Epinephrine infusion [0.01 mcg/(kg min)] restores adequate pressures and flows, increasing LVOT VTI to 12.7 cm, SV to 49 ml (3.90 cm2 × 12.7 cm), heart rate to 120 bpm and CO to 5.83 L/min (c). LVOT left ventricular outflow tract, VTI Doppler velocity–time integral, CO cardiac output

Inadequate central blood volume

After the first phase of shock resuscitation, signs of severe hypovolemia may still exist and be detected as a small LV end-diastolic area (LVEDA, easily measured in a TTE parasternal short axis or in a TEE transgastric midpapillary view). But most frequently a volume-resuscitated shock will need a volume responsiveness assessment in order to unmask a persistent preload defect [37]. Volume responsiveness can be detected with various ECHO indices (Table 3), but this assessment must be tailored to the clinical setting. In fully passive mechanically ventilated patients with sinus rhythm, indices derived from study of heart–lung interactions are highly accurate: ≥12.5% respiratory variation of LV ejection [38], ≥18% inferior vena cava distensibility [39] (TTE subcostal view), or ≥36% superior vena cava collapsibility [40] (TEE bicaval view) are validated cutoffs, with sensitivities and specificities ranging from 90 to 100% (Fig. 4). Low tidal volumes may yield false negatives [41], and severe RV dysfunction, for LVOT flows-based indices, false positives [42]. Spontaneous breathing and/or non-sinus rhythm requires a passive leg-raising test: a ≥12.5% LVOT velocity–time integral increase upon shift of patient position from 45° trunk elevation to 45° leg raising is predictive of SV increase with volume loading (Fig. 2 ESM) with 77% sensitivity and 100% specificity [43]. False negatives to the test may occur, especially in the context of abdominal hypertension for values of intrabdominal pressure >16 mmHg [44]. When still in doubt, an Echo-monitored fluid challenge (the search for ≥15% Echo-measured stroke volume increase upon a limited fluid bolus infusion) is indicated as last choice. Of note is that the existence of volume responsiveness is better supported by a bundle of ECHO findings rather than a single positive index, and that it does not necessarily equate to the need for fluid infusion (absolute hypovolemia correction); also recruitment of unstressed volume from the venous reservoir (relative hypovolemia correction) may increase cardiac output [45, 46]: when an upward titration of vasoconstrictors determines an increase in stroke volume, this may be the preferred choice toward limiting harmful positive fluid balance [47].

Volume responsiveness assessment by means of heart–lung interaction-derived indices, in a mechanically ventilated passive patient with septic shock. Septic shock patient with peritonitis caused by colonic perforation. Left-sided panels show a volume responsiveness status, with marked respiratory SVC collapsibility (56%; a, TEE bicaval view, M-mode scanning), IVC distensibility (32%; c, TEE transgastric off-axis view on the IVC, M-mode scanning) and marked LV ejection respiratory variations (36%; e, TEE deep transgastric view, Doppler sampling of LVOT velocities). After 1,500 ml fluid infusion, these respiratory variations are greatly reduced and the various indices show now absence of volume responsiveness (right-sided panels): SVC collapsibility 18% (b), IVC distensibility 5% (d), LV ejection respiratory variations 10% (f). SVC superior vena cava, IVC inferior vena cava, SVCexp SVC diameter at end-expiration, SVCinsp SVC diameter at end-inspiration, IVCinsp IVC diameter at end-inspiration, IVCexp IVC diameter at end-expiration, Vpeak aortic blood flow velocity, VpeakMAX maximum Vpeak velocity, VpeakMIN minimum Vpeak velocity

LV systolic dysfunction

LV systolic function is assessed either visually (qualitatively), or by means of widely used 2D measurements (quantitatively). These are based on the percentage variation of LV size from end-diastole to end-systole, either referring to its diameter (FS, fractional shortening), its area (FAC, fractional area change), or its volume (EF, ejection fraction).

LV sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction is nowadays a well-known entity [48], and both global and regional systolic wall motion abnormalities can be found [49, 50]. A so-called hypodynamic pattern (low cardiac index associated with reduced ejection fraction, EF, below 40–45%) is described in up to 60% of SS patients [14, 51]: its detection should prompt inotropes administration, even if central venous pressure values indicated by guidelines as target for ceasing volume loading have not been reached yet (further increase in preload on an acutely failing LV may not only fail to increase oxygen delivery but may also cause harm). Sequential determinations of EF, FAC and FS will allow for appreciation of LV dysfunction’s complete recovery in survivors (Fig. 5, Video 5A, C ESM) [52, 53]. Time pattern of this phenomenon has been characterized: dysfunction appears usually on day 1 roughly in two-thirds of affected patients, on day 2–3 in the other third, while recovery takes 7–10 days. (Fig. 3 ESM) [51]. As sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction can be masked by associated vasodilatation and preload inadequacy, LV systolic function should always be re-assessed after preload and afterload optimization (Fig. 6, Video 6A, B). Conversely to what previously believed, there is no LV adaptive dilatation to this transient systolic function reduction (a relevant increase in chamber dimension to compensate for a reduced contractility): even if referred to as “dilatation” also by some recent echocardiographic literature[54], no acute relevant increase of LV size beyond upper limits of the normality range is to be expected in a previously healthy septic-depressed LV [53, 55], but rather changes is LV size according to different loading conditions in distinct phases of SS. Of note, ECG helps to distinguish between acute coronary syndrome-determined dysfunction triggered by sepsis (with electrical signs of ischemia) from true sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction (negative ECG for ischemia). Cardiac troponins show increases in both cases [56]. Myocardial perfusion ECHO may be a promising technique to allow for differential diagnosis [57].

Sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction. Septic shock in a patient with community-acquired pneumonia (same patient of Fig. 3). Repeated TEE assessments (mid-esophageal 4-chamber views). At ICU admission [SAP 110/70 mmHg, HR 118 bpm, norepinephrine 0.4 mcg/(kg min)] a pattern of severe biventricular dysfunction is detected (Video 5A ESM), as evidenced by a small reduction of both ventricle’s size from end-diastole (a) to end-systole (d); measured EF is 15%, TAPSE 12,9 mm, CO 3,59 L/min. Hemodynamic improvement occurs after epinephrine infusion at [0.1 mcg/(kg min)] (b–e, Video 5B ESM): SAP 140/76, HR 122 bpm, EF 25%, TAPSE 15.7 mm, CO 4.83 L/min. On day 12 patient is weaned from vasoactive drugs (c–f, Video 5C ESM): SAP 130/68, HR 93 bpm, EF 58%, TAPSE 21.1 mm, CO 6.43 L/min. Note that the LV looks dilated in a and b, but only if compared with its size after recovery (c), and not as absolute value (LV EDV = 146 ml, upper range of normality). RA right atrium, RV right ventricle, LA left atrium, LV left ventricle, EF ejection fraction, TAPSE tricuspid annulus plane systolic excursion, CO cardiac output

Septic shock after preload and afterload optimization, unmasking sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction. Same patient of Fig. 1 (hospital-acquired pneumonia, 3rd postoperative month of double-lung transplant), 18 h later, after volume resuscitation, infusion of norepinephrine [1 mcg/(kg min)], vasopressin 0.02 U/min, now again unstable (SAP 90/60, HR 121 bpm, low cardiac output). TTE subcostal 4-chamber view (upper panels, Video 6A ESM) and parasternal short axis midpapillary view (middle panels, Video 6B ESM) show a severely depressed LV systolic function with negligible reduction of LV size from end-diastole (a, c) to end-systole (b, d). RV shows preserved systolic function. The IVC (subcostal IVC view, lower panels) is now larger (e) with absent inspiratory increase at mechanical passive inspiration (f). RA right atrium, RV right ventricle, LA left atrium, LV left ventricle, IVC inferior vena cava, SAP systemic arterial pressure, HR heart rate

RV systolic dysfunction

RV systolic dysfunction can also develop in SS, and it is been described in up to one-third of patients [14, 58]. It can either be part of biventricular dysfunction or represent an isolated RV dysfunction. Intrinsic depression of RV myocardial function is detected as RV hypokinesia, and semi-quantitatively appreciated as a variable degree of RV dilatation (with RV end-diastolic area, RVEDA, to LV end-diastolic area, LVEDA, ratio measurement in a four chamber view). When RV systolic overload (due to ARDS, mechanical ventilation) develops [59], or even worse superimposes on an already poor RV function, an overt state of acute cor pulmonale can appear, and it is revealed by septal dyskinesia (Fig. 7, Video 7A, B) [60]. With introduction of lung protective ventilation strategies, frequency of this phenomenon has markedly decreased [61], and RV dilatation represents the most frequent finding. Such as LV dysfunction may be unmasked by vasoconstrictors administration, so can RV failure become manifest only upon institution of mechanical ventilation. Time course of sepsis-related RV dysfunction resembles that of LV dysfunction [48]. Whenever detected as main hemodynamic feature (in the ARDS setting), not only inotropes administration but also vasoconstrictors upward titration is indicated, together with low plateau pressure of ventilation; this hemodynamic pattern may also represent an indication for inhaled nitric oxide administration and for patient’s pronation [60, 61].

Acute cor pulmonale in septic shock. Septic shock in community-acquired pneumonia superimposed on chronic pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary fibrosis). TEE midesophageal 4-chamber view (upper panels, Video 7A ESM) and transgastric midpapillary short axis view (lower panels, Video 7B ESM). SAP 100/53 mmHg, HR 123 bpm, low cardiac output. Norepinephrine [1 mcg/(kg min)] is infused. The RV looks markedly dilated (its end-diastolic area is bigger than the LV area (7A, RVEDA/LVEDA > 1), and hypokinetic (small reduction of its size from end-diastole, a, to end-systole, b). The interventricular septum is flattened (a, c) and shows a paradoxical motion at end-systole (b, d, red arrow). RA right atrium, RV right ventricle, LA left atrium, LV left ventricle, RVEDA RV end-diastolic area, LVEDA LV end-diastolic area

Low peripheral vascular tone

Echocardiography offers theoretically the tools to calculate systemic arterial vascular resistance but with a cumbersome method and infrequent clinical applicability. In clinical practice, sepsis-related vasodilatation is diagnosed with exclusion criteria: persistence of hypotension despite adequate preload and preserved (or pharmacologically normalized) biventricular systolic function, and thus absence of a low-output state, invariably means a need for an increase in systemic arterial vascular tone [15]. As mentioned above, also in some situations of volume responsiveness upward titration of vasoconstrictors is indicated.

LV diastolic dysfunction, LV filling pressure

Additionally, assessment of LV diastolic properties and LV filling pressures estimation may be of use. Diastolic dysfunction has been demonstrated in SS patients using relatively preload-independent parameters, based on mitral annulus tissue Doppler and mitral inflow propagation velocity; not only as associated with systolic dysfunction, but also as isolated impairment of LV relaxation [62, 63]. Even if clinical implications of this still have to be fully clarified, practical impact may be derived for patients with isolated diastolic dysfunction and evidence of elevated LV filling pressures in the context of hypoxemia: fluid restriction and diuretics are then consistent choices (patients with systolic dysfunction do not viceversa risk to remain undetected, as they already usually are submitted to such a tretment, toghether with inotropes). Various Doppler-derived parameters provide estimation of LV filling pressure with good correlation to invasively measured pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP), specifically in septic shock patients populations [64]. In mechanically ventilated patients, mitral E/A < 1.4, pulmonary vein S/D > 0.65 and systolic fraction >44% best predict a PAOP ≤ 18 mmHg [65]; lateral E/E′ < 8.0 or E/Vp < 1.7 predicts a PAOP ≤ 18 mmHg with a sensitivity of 83 and 80% [65]; mitral E/A > 2 predicts a PAOP > 18 mmHg with 100% positive predictive value [66].

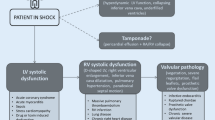

A structured approach integrating assessment of these hemodynamic targets into a practical algorithm is proposed in Fig. 8.

Septic Shock ECHO-based goal-directed algorithm. To monitor hemodynamics in septic shock the targets of the echocardiographic investigation are organized in a systematic five-step approach. Starting point is to detect potential signs of pre-existing chronic cardiac dysfunction (Step 1): LV or LA significant dilatation, and LV marked hypertrophy are signs or chronic volume/pressure overload; RA significant dilatation, RV dilatation and hypertrophy have the same meaning for right-side chronic disease (isolated RV dilatation can vice versa be a sign of acute RV dysfunction). If unrecognized, these findings can mislead in interpretation of subsequent findings (i.e. primary cardiogenic cause of shock, instead of sepsis; wrong assessment of volume status based on LV or RV dimensions). LV and RV systolic function must then be assessed (Step 2), together with cardiac output Doppler measurement (Step 3). A low output state can then be ascribed to sepsis-related LV systolic dysfunction (associated or not to RV dysfunction) or isolated RV dysfunction, and treated accordingly. Low output with evidence of normal biventricular systolic function should prompt investigation of volume status (Step 4): overt hypovolemia or presence of volume responsiveness will lead to fluid infusion. When inadequacy of global perfusion and/or hypotension is associated with a non-low output state, persistent preload defect should be investigated (again step four) and if detected corrected. If this is not the case, an exclusion diagnosis of vasodilatation is made (Step 5), and systemic arterial tone corrected with upward titration of vasopressors. Whenever this is done, LV systolic function should subsequently be re-assessed, as normalization of LV afterload can unmask sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction. If chronic LV failure is found, or LV dysfunction develops acutely, LV filling pressure estimation is mandatory, to guide fluid management and differential diagnosis of potential hypoxemia and pulmonary edema (cardiogenic vs. non cardiogenic). ScvO2 central venous saturation, LV left ventricle, RV right ventricle, SV stroke volume, CI cardiac index, SAPm mean systemic arterial pressure

Cardiac source of sepsis

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a microbial infection of intracardiac structures facing the blood. It can be encountered in ICU patients mainly in two scenarios: (A) as cause of admission, due to severity of its complications leading to cardiogenic shock in a febrile context, or to pure septic shock; (B) as acquired infection during ICU stay, leading to a septic state with no evident focus.

-

IE on native or prosthetic valves is defined on the bases of a well-established set of diagnostic criteria [67, 68], and echocardiography provides for one of the major ones. IE is a severe disease with a high mortality, ranging from 20 to 25% [69] and up to 45% in patients then admitted to ICU [70]. Echocardiography highly contributes to IE diagnosis, allows for severity assessment, and has a pivotal role in IE management and decision making both on therapy and complications [71, 72].

Three potential ECHO findings are deemed to be important criteria in establishing an IE diagnosis (Table 4): (A) mobile echo dense mass attached to valvular or mural endocardium or to implanted material (Fig. 9a–d, Video 9A, B, Video 10–11 ESM), (B) paravalvular fistulae or abscess formation (Fig. 9d, Video 12 ESM), and (C) new disruption or dehiscence of a prosthetic valve (paravalvular leak) (Video 13 ESM). In severely damaged native valves (especially rheumatic), clear identification of small vegetations may be very difficult. Differential diagnosis between prosthetic valve IE and non-obstructive thrombus, or between bioprosthetic valve IE and degeneration, can be very challenging.

Table 4 Echocardiographic findings suggestive of endocarditis Fig. 9 Infectious endocarditis in ICU patients. a Patient with septic shock, acute pulmonary edema, and systemic arterial embolization (TEE midesophageal long axis view): massive mobile vegetation (white arrow) on native aortic valve (right cusp; note also anatomic disruption of the non-coronary cusp). See also Video 9A, B ESM. b Febrile dyspnoeic patient (TEE midesophageal long axis view): thin vegetations and cusps perforation on native aortic valve (white arrows). See also Video 10 ESM. c Septic shock patient (TEE midesophageal commissural view): small linear vegetation (white arrow) on prosthetic valve in mitral position. See also Video 11 ESM. d Patient with cardiac tamponade (bloody fluid at pericardiocentesis) and septic shock (TEE midesophageal 2-chamber view): huge mobile vegetation incorporating the posterior mitral leaflet (white arrow); note sub-annular abscess and escavation (red arrow) responsible for subacute LV wall rupture and hemopericardium. See also Video 12 ESM. In Video 13 ESM see in another febrile ICU patient a paravalvular leak, regurgitant jet originating outside the prosthetic valve annulus (red arrow; TEE midesophageal 2-chamber view, mechanical bileaflet valve in mitral position). e Febrile patient with dilated cardiomyopathy and biventricular pacing device (TEE bicaval view): thrombus is evident in the SVC (red arrow), attached to the pacemaker wire (white arrow). See also Video 14 ESM. Note pulmonary embolic lesion at CT-scan (f, red arrow). RA right atrium, LA left atrium, LV left ventricle, Asc AO ascending aorta, SVC superior vena cava

Relevant differences in diagnostic accuracy for IE exist between the transthoracic and the transesophageal technique. Compared with TTE [73, 74], TEE has greater sensitivity on small vegetations and on mitral valve IE. Both techniques reach high specificity in equal manner, and detection of a vegetating mass with focused TTE in first approach to a shocked patient can be lifesaving.

The clinical context influences TTE and TEE diagnostic capability [75]: while with low IE pre-test probability a negative good-quality TTE can exclude the diagnosis, TEE should be performed on all TTE negative cases with a more-than-low clinical suspicion.

In mechanically ventilated ICU patients TEE is almost invariably needed. It is then mandatory in the assessment of suspected prosthetic valves IE, and in TTE positive cases to identify major valvular complications and guide surgical planning [76].

Of particular note is that the clinical presentation of IE in acutely ill patients can be very much variable, ranging from a febrile state, to septic or cardiogenic shock, to any embolic manifestation. Echocardiography alone cannot be used to make diagnosis of IE: a combination of clinical-instrumental-microbiological criteria is required, and differential diagnosis between IE vegetations and other intracardiac masses should always be considered.

Even if one-third to a half of IE develop in absence of pre-existing cardiac pathology or prosthetic devices, a high suspicion for IE should be kept for septic patients with prosthetic valves, implantable devices, or known significant native valve pathology, and for ICU bacteriemic patients with unknown septic focus.

-

IE on indwelling central venous catheters or implantable devices (pace-makers, internal cardioverters-defibrillators) is uncommon due to the lack of the hemodynamic factors usually involved in IE pathogenesis (flow turbulence, high pressure gradients) [77], but is getting more frequent as a consequence of development and increased use of invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. In an ICU septic patient with no other clear infective focus it should thus be considered, especially if evidence of pulmonary septic embolism exists [78] (Fig. 9e, f, Video 14 ESM). Besides searching for vegetations on the catheter, from superior vena cava to its implantation on the myocardium, the ECHO exam should seek carefully for IE-associated localizations on right heart valves [77–81]. Visualizing vegetations on implantable devices (mass or sleeve-like) may be difficult, due to artifacts coming from the device itself. Small fibrin strands may represent a difficult differential diagnosis.

-

Septic thrombus on temporary central venous catheters in ICU patients [82] and right heart endocarditis following pulmonary heart catheterization have also been described [83]. Finding of masses on central venous catheters, more frequent, should prompt to consider non-septic thrombosis as differential diagnosis with EI. Microbiological data become obviously crucial.

Limitations of Echo in diagnosis and monitoring the critical septic patient

Even if ECHO has been extensively validated as accurate and safe, and is currently employed on septic critical patients by many clinicians, real outcome data related to its use (beyond simple demonstration on impact on patient management) are lacking.

Limitations in its use also exist. Low echogenicity at surface examination matched with contraindications to TEE clearly prevent its use. Whenever there is strict requirement of continuous monitoring (of cardiac output or pulmonary artery pressure) or precise measurement rather than estimation of deemed relevant variables (mainly PAOP or extravascular lung water), ECHO is not the right tool. In centres where a tradition and adequate training on the use of critical care ECHO exist, this is no frequent [14], and repeated bedside assessment and semi-quantification of hemodynamic variables enable use of ECHO alone as monitoring tool. As it happens with targets of critical care practice other than hemodynamics, integrated monitoring remains fundamental, and ECHO is in the best position to be used in conjunction with other devices (pulse contour technique based cardiac output monitors, pulmonary artery catheter, PiCCO) [13]. Indeed, it can guide choice between them and timing of use. A final issue is represented by time required to the clinician to acquire sufficient competence in critical care ECHO. For applications beyond focused ECHO, particularly comprehensive hemodynamic monitoring, the training may in fact be demanding [8], and not all physician may be willing to undergo a dedicated training.

Conclusions

Echocardiography marries diagnostic capability with monitoring accuracy, morphological assessment with functional investigation. In the complex scenario of the critical septic patient it has therefore the potential to be regarded as an ideal monitoring tool, in most circumstances used alone, sometimes in combination with other devices. Beyond the very first stages of septic shock, where focused ECHO may suffice, a comprehensive systematic ECHO assessment of cardiac output, left and right systolic ventricular function, volume status and filling pressures is required, and allows for effective hemodynamic management. Unfortunately, outcome studies on the use of ECHO in septic shock are lacking, and are therefore strongly advocated. As a matter of fact, availability of ECHO equipment and adequate training remain actual major limitations on a wider use of ECHO in this setting.

References

Angus DC (2001) Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the USA: analysis of incidence, outcome and costs of care. Crit Care Med 29:1303–1310

Brun-Buisson C (1995) Incidence, risk factors and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults: a multicenter prospective study in ICU. JAMA 274:968–974

Magder S (1993) Shock physiology. In: Pinsky M et al (eds) Pathophysiologic foundations of critical care. William & Wilkins, Baltimore, pp 140–160

Annane D, Bellissant E, Cavaillon JM (2005) Septic shock. Lancet 365:63–78

TTE/TEE Appropriateness Criteria Writing Group, Douglas PS, ACCF Appropriateness Criteria Working Group. American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group; American Society of Echocardiography; American College of Emergency Physicians; American Society of Nuclear Cardiology; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography; Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (2007) ACCF/ASE/ACEP/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR 2007 appropriateness criteria for transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography: a report of the ACCF/ASE/ACEP/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR. Endorsed by SCCP and SCCM. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 20:787–805

Cholley BP, Vieillard-Baron A, Mebazaa A (2006) Echocardiography in ICU: time for widespread use. Intensive Care Med 32:9–10

Seppelt IM (2007) All intensivists need echocardiography skills in the 21st century. Crit Care Resusc 9:286–288

Price S, Via G, Sloth E, Guarracino F, Breitkreutz R, Catena E, Talmor D, World Interactive Network Focused On Critical Ultrasound ECHO-ICU Group (2008) Echocardiography practice, training and accreditation in the intensive care: document for the World Interactive Network Focused on Critical Ultrasound (WINFOCUS). Cardiovasc Ultrasound 6:49

Price S, Nicol E, Gibson DG, Evans TW (2006) Echocardiography in the critically ill: current and potential roles. Intensive Care Med 32: 48–59

Boyd JH, Walley KR (2009) The role of echocardiography in hemodynamic monitoring. Curr Opin Crit Care 15:239–243

Breitkreutz R, Walcher F, Seeger FH (2007) Focused echocardiographic evaluation in resuscitation management: concept of an advanced life support-conformed algorithm. Crit Care Med 35:S150–S161

Manasia AR, Nagaraj HM, Kodali RB, Croft LB, Oropello JM, Kohli-Seth R, Leibowitz AB, DelGiudice R, Hufanda JF, Benjamin E, Goldman ME (2005) Feasibility and potential clinical utility of goal-directed transthoracic echocardiography performed by noncardiologist intensivists using a small hand-carried device (SonoHeart) in critically ill patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 19:155–159

Vignon P (2005) Hemodynamic assessment of critically ill patients using echocardiography Doppler. Curr Opin Crit Care 11:227–234

Vieillard-Baron A, Prin S, Chergui K, Dubourg O, Jardin F (2003) Hemodynamic instability in sepsis: bedside assessment by Doppler echocardiography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168:1270–1276

Via G, Mongodi S, Venti A, Mojoli F (2009) Ultrasound-enhanced hemodynamic monitoring: echocardiography as a monitoring tool. Minerva Anestesiol 75(Suppl. 1 to No. 7–8): 178–184

Hüttemann E, Schlenz C, Kara F (2004) The use and safety of TEE in the general ICU—a minireview. Acta Aanaesthesiol Scand 48:827–836

Orme RM, Oram MP, McKinstry CE (2009) Impact of echocardiography on patient management in the intensive care unit: an audit of district general hospital practice. Br J Anaesth 102:340–344

Charron C, Caille V, Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A (2006) Echocardiographic measurement of fluid responsiveness. Curr Opin Crit Care 12:249–254

Bouferrachea K, Caille V, Chimot L, Castro S, Charron C, Page B, Vieillard-Baron A (2010) Monitorage hémodynamique dans le sepsis: confrontation des recommandations de la Surviving Sepsis Campaign à l’échocardiographie. Réanimation 19S:S32–S33 (Abst)

Vieillard-Baron A, Charron C, Chergui C, Peuyrouset O, Jardin F (2006) Bedside echocardiographic evaluation of hemodynamics in sepsis: is a qualitative evaluation sufficient? Intensive Care Med 32:1547–1552

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M (2001) Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 345:1368–1377

Rivers EP, Coba V, Whitmill M (2008) Early goal-directed therapy in severe sepsis and septic shock: a contemporary review of the literature. Curr Opin Anesthesiol 21:128–140

Zanotti Cavazzoni SL, Dellinger RP (2006) Hemodynamic optimization of sepsis-induced hypoperfusion. Crit Care 10(Suppl 6):S2

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, Reinhart K, Angus DC, Brun-Buisson C, Beale R, Calandra T, Dhainaut JF, Gerlach H, Harvey M, Marini JJ, Marshall J, Ranieri M, Ramsay G, Sevransky J, Thompson BT, Townsend S, Vender JS, Zimmerman JL, Vincent JL (2008) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Intensive Care Med 36:296–327

Jones AE, Tayal S, Sullivan M, Kline JA (2004) Randomized, controlled trial of immediate versus delayed goal-directed ultrasound to identify the cause of nontraumatic hypotension in emergency department patients. Crit Care Med 32:1703–1708

Leung JM, Levine EH (1994) LV end systolic cavity obliteration as an estimate of intraoperative hypovolemia. Anesthesiology 81:1102–1109

Lyon M, Blaivas M, Branman M et al (2005) Sonographic measurement of the inferior vena cava as a marker of blood loss. Am J Em Med 23:45–50

Lichtenstein D, Jardin F (1994) Appréciation non invasive de la pression veineuse centrale par la mesure échogaphique deu calibre de la veine cave inférieure en réanimation. Réanimation Urg 3:79–82

Cheung AT, Savino JS, Weiss SJ et al (1994) Echocardiographic and Hemodynamic indexes of LV preload in patients with normal and abnormal ventricular function. Anesthesiology 81:376–387

Neri L, Storti E, Lichtenstein D (2007) Toward a ultrasound curriculum for critical care medicine. Crit Care Med 35(Suppl):S290–S304

Lichtenstein D (2007) Point-of-care ultrasound: Infection control in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 35(Suppl):S262–S267

Griffee MJ, Merkel MJ, Wei KS (2010) The role of echocardiography in hemodynamic assessment of septic shock. Crit Care Clin 26:365–368

Hollenberg SM, Ahrens TS, Annane D, Astiz ME, Chalfin DB, Dasta JF, Heard SO, Martin C, Napolitano LM, Susla GM, Totaro R, Vincent JL, Zanotti-Cavazzoni S (2004) Practice parameters for hemodynamic support of sepsis in adult patients. 2004 update. Crit Care Med 32:1928–1948

Feinberg MS, Hopkins WE, Davila-Roman VG, Barzilai B (1995) Multiplane transesophageal echocardiographic doppler imaging accurately determines cardiac output measurements in the critically ill patients. Chest 107:769–773

Poelaert J, Schmidt C, Van Aken H, Hinder F, Mollhoff T, Loick HM (1999) A comparison of transoesophageal echocardiographic Doppler across the aortic valve and the thermodilution technique for estimating cardiac output. Anaesthesia 54:128–136

Jardin F, Bourdarias JP (1995) Right heart catheterization at bedside: a critical view. Intensive Care Med 21:291–295

Jardin F (1999) Persistent preload defect in severe sepsis despite fluid loading: a longitudinal echocardiographic study in patients with septic shock. Chest 116:1354–1359

Feissel M, Michard F, Mangin I, Ruyer O, Faller JP, Teboul JL (2001) Respiratory changes in aortic blood velocity as an indicator of fluid responsiveness in ventilated patients with septic shock. Chest 119:867–873

Barbier C, Loubières Y, Schmit C, Hayon J, Ricôme JL, Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A (2004) Respiratory changes in inferior vena cava diameter are helpful in predicting fluid responsiveness in ventilated septic patients. Intensive Care Med 30:1740–1746

Vieillard-Baron A, Chergui K, Rabiller A, Peyrouset O, Page B, Beau-chet A, Jardin F (2004) Superior vena caval collapsibility as a gauge of volume status in ventilated septic patients. Intensive Care Med 30:1734–1739

De Backer D, Heenen S, Piagnerelli M, Koch M, Vincent JL (2005) Pulse pressure variations to predict fluid responsiveness: influence of tidal volume. Intensive Care Med 31:517–523

Mahjoub Y, Pila C, Friggeri A, Zogheib E, Lobjoie E, Tinturier F, Galy C, Slama M, Dupont H (2009) Assessing fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients: False-positive pulse pressure variation is detected by Doppler echocardiographic evaluation of the right ventricle. Crit Care Med 37:2570–2575

Lamia B, Ochagavia A, Monnet X, Osman D, Maizel J, Richard C, Chemla D (2007) Echocardiographic prediction of volume responsiveness in critically ill patients with spontaneous breathing activity. Int Care Med 32:1125–1132

Mahjoub Y, Touzeau J, Airapetian N, Lorne E, Hijazi M, Zogheib E, Tinturier F, Slama M, Dupont H (2010) The passive leg-raising maneuver cannot accurately predict fluid responsiveness in patients with intra-abdominal hypertension. Crit Care Med 38:1824–1829

Monnet X, Jabot J, Maizel J, Gharbi R, Richard C, Teboul J-L (2010) La noradrénaline réduit la précharge-dépendance en recrutant du volume sanguin non contraint chez les patients septiques. Réanimation 19S:S34 (Abst)

Hamzaoui O, Georger JF, Monnet X, Ksouri H, Maizel J, Richard C, Teboul JL (2010) Early administration of norepinephrine increases cardiac preload and cardiac output in septic patients with life-threatening hypotension. Crit Care 14:R14

Alsous F, Khamiees M, DeGirolamo A, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA (2000) Negative fluid balance predicts survival in patients with septic shock: a retrospective pilot study. Chest 117:1749–1754

Rabeul C, Mebazaa A (2006) Septic shock: a heart story since the 1960s. Intensive Care Med 32:799–807

Ellrodt AG (1985) LV performance in septic shock: reversible segmental and global abnormalities. Am Heart J 110:402–409

Jardin F (1990) Sepsis-related cardiogenic shock. Crit Care Med 18:1055–1060

Vieillard-Baron CailleV, Charron C et al (2008) The actual incidence of global left ventricular hypokinesia in adult septic shock. Crit Care Med 36:1701–1706

Parker MM (1984) Profound but reversible myocardial depression in patients with septic shock. Ann Int Med 100:483–496

Vieillard-Baron A (2001) Early preload adaptation in septic shock? A TEE study. Anesthesiology 94:400–406

Bouhemad B, Nicolas-Robin A, Arbelot C, Arthaud M, Fégere F, Rouby J-J (2009) Acute left ventricular dilatation and shock-induced myocardial dysfunction. Crit Care Med 37:441–447

Etchecopar-Chevreuil C, François B, Clavel M, Pichon N, Gastinne H, Vignon P (2008) Cardiac morphological and functional changes during early septic shock: a transesophageal echocardiographic study. Intensive Care Med 34:250–256

Maeder M (2006) Sepsis-associated myocardial dysfunction: diagnostic and prognostic impact of cardiac troponins and natriuretic peptides. Chest 129:1349–1366

Sado D, Greaves K (2010) Myocardial perfusion echocardiography: a novel use in the diagnosis of sepsis-induced left ventricular systolic impairment on the intensive care unit. Eur J Echocardiogr (Epub ahead of print)

Kimchi A, Ellrodt AG, Berman DS, Riedinger MS, Swan HJ, Murata GH (1984) Right ventricular performance in septic shock: a combined radionuclide and hemodynamic study. JACC 4:945–951

Sibbald WJ, Paterson NA, Holliday RL, Anderson RA, Lobb TR, Duff JH (1978) Pulmonary hypertension in sepsis: measurement by the pulmonary artery diastolic-pulmonary wedge pressure gradient and the influence of passive and active factors. Chest 73:583–591

Vieillard-Baron A, Schmitt JM, Augarde R, Fellahi JL, Prin S, Page B, Beauchet A, Jardin F (2001) Acute cor pulmonale in ARDS submitted to protective ventilation: incidence, clinical implications, and prognosis. Crit Care Med 29:1551–1555

Vieillard-Baron A, Jardin F (2007) Is there a safe plateau pressure in ARDS: the right heart only knows. Intensive Care Med 33:444–447

Bouhemad B, Nicolas-Robin A, Arbelot C, Arthaud M, Fégere F, Rouby J-J (2008) Isolated and reversible impairment of ventricular relaxation in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 36:766–774

Poelaert J, Declerck C, Vogelaers D, Colardyn F, Visser CA (1997) Left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in septic shock. Intensive Care Med 23:553–560

Mousavi N, Czarnecki A, Ahmadie R, Tielan F, Kumar K, Lytwyn M, Kumar A, Jassal DS (2010) The utility of tissue Doppler imaging for the noninvasive determination of left ventricular filling pressures in patients with septic shock. J Intensive Care Med 25:163–167

Vignon P, AitHssain A, François B, Preux PM, Pichon N, Clavel M, Frat JP, Gastinne H (2008) Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary artery occlusion pressure in ventilated patients: a transoesophageal study. Crit Care 12:R18

Boussuges A, Blanc P, Molenat F, Burnet H, Habib G, Sainty JM (2002) Evaluation of left ventricular filling pressure by transthoracic Doppler echocardiography in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 30:362–367

Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK (1994) New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Am J Med 96:200–209

Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler VG Jr, Ryan T, Bashore T, Corey GR (2000) Proposed modifications to Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 30:633–638

Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB (2001) Infective endocarditis in adults. NEJM 345:1318–1330

Mourvillier B, Trouillet JL, Timsit JF, Baudot J, Chastre J, Régnier B, Gibert C, Wolff M (2004) Infective endocarditis in the ICU: clinical spectrum and prognostic factors in 228 consecutive patients. Intensive Care Med 30:2046–2052

Perron JM (2001) Échocardiographie dans la prise en charge de l’endocardite infectiouse. Arch Mal Cœur 94:29–37

Flachskampf FA, Daniel WG (2000) Role of TEE in infective endocarditis. Heart 84:3–4

Erbel R, Rohmann S, Drexler M, Mohr-Kahaly S, Gerharz CD, Iversen S, Oelert H, Meyer J (1988) Improved diagnosis value of echocardigraphy in patients with infective endocarditis by TEE approach: a prospective study. Eur Heart J 9:45–53

Roudaut R (1993) Appport diagnostique de l’échocardiographie transœsophagienne dans les endocardites infectieuses: fiabilité et limites. Arch Mal Cœur 86:1819–1823

Lindner JR, Case RA, Dent JM, Abbott RD, Scheld WM, Kaul S (1996) Diagnostic value of echocardiography in suspected endocarditis. An evaluation based on the pretest probability of disease. Circulation 93:730–736

Daniel WG, Mügge A, Grote J, Hausmann D, Nikutta P, Laas J, Lichtlen PR, Martin RP (1993) Comparison of TTE and TEE for detection of abnormalities of prosthestic and bioprosthetic valves in the mitral and aortic position. Am J Cardiol 71:210–215

Victor F, De Place C, Camus C, Le Breton H, Leclercq C, Pavin D, Mabo P, Daubert C (1999) Pacemaker lead infection: echocardiographic features, management, and outcome. Heart 81:82–87

Weber T, Huemer G, Tschernich H, Kranz A, Imhof M, Sladen RN (1998) Catheter-induced thrombus in the superior vena cava diagnosed by TEE. Acta Anaesth Scand 42:1227–1230

Yamashita S, Noma K, Kuwata G, Miyoshi K, Honaga K (2005) Infective Endocarditis at the tricuspid valve following central venous catheterization. J Anesth 19:84–87

Cohen GI, Klein AL, Chan KL, Stewart WJ, Salcedo EE (1992) TEE diagnosis of right sided cardiac mass in patients with central lines. Am J Cardiol 70:925–929

Vilacosta I, Sarriá C, San Román JA, Jiménez J, Castillo JA, Iturralde E, Rollán MJ, Martínez Elbal L (1994) Usefulness of TEE for diagnosis of infected transvenous permanent pacemakers. Circulation 89:2684–2687

Garcia E, Granier I, Geissler A, Boespflug MD, Magnan PE, Durand-Gasselin J (1997) Surgical management of Candida suppurative thrombophlebitis of superior vena cava after central venous catheterization. Intensive Care Med 23:1002–1004

Rowley KM, Clubb KS, Smith GJ, Cabin HS (1984) Right-sided infective endocarditis as a consequence of flow-directed pulmonary-artery catheterization. NEJM 311:1152–1156

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 9 (MPG 338 kb)

Supplementary material 10 (MPG 236 kb)

Supplementary material 12 (MPG 401 kb)

Supplementary material 13 (MPG 664 kb)

Supplementary material 14 (MPG 499 kb)

Supplementary material 15 (MPG 517 kb)

Supplementary material 16 (MPG 295 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Via, G., Price, S. & Storti, E. Echocardiography in the sepsis syndromes. Crit Ultrasound J 3, 71–85 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13089-011-0069-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13089-011-0069-0