Abstract

This work aims to contribute to addressing the global challenge of recycling and valorising spent potlining; a hazardous solid waste product of the aluminium smelting industry. This has been achieved using a simple two-step chemical leaching treatment of the waste, using dilute lixiviants, namely NaOH, H2O2 and H2SO4, and at ambient temperature. The potlining and resulting leachate were characterised by spectroscopy and microscopy to determine the success of the treatment, as well as the morphology and mineralogy of the solid waste. This confirmed that the potlining samples were a mixture of contaminated graphite and refractory materials, with high variability of composition. A large quantity of fluoride was solublised by the leaching process, as well as numerous metals, some of them toxic. The acidic and caustic leachates were combined and the aluminium and fluoride components were selectively extracted, using a modified ion-exchange resin, in fixed-bed column experiments. The resin performed above expectations, based on previous studies, which used a simulant feed, extracting fluoride efficiently from leachates of significantly different compositions. Finally, the fluoride and aluminium were coeluted from the column, using NaOH as the eluent, creating an enriched aqueous stream, relatively free from contaminants, from which recovery of synthetic cryolite can be attempted. Overall, the study accomplished several steps in the development of a fully-realised spent potlining treatment system.

Graphic Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spent potlining (SPL) is a hazardous waste product of aluminium smelting operations, which is generated at the end of the lifespan of a smelter electrolysis cell. There are two distinct fractions, these being “first-cut”, composed mainly of graphitic material from exhausted cathode blocks, and “second-cut”, formed mainly of cement and brick. Both cuts are heavily contaminated with fluoride-bearing compounds, with reported fluoride concentrations ≤ 20% [1]. Various other chemical species are also present, including ≤ 1% cyanides [2]. Estimates for the average mass of SPL generated per tonne of aluminium produced vary between 7 and 50 kg [3], but an average of ~ 25 kg is frequently given [4, 5]. The estimated global production of aluminium in 2018 was 64.3 MT, meaning ~ 1.61 MT of SPL was also created [6]. Of this, it is estimated that 50–75% of the waste was deposited either in landfill facilities or over-ground buildings [1, 7].

Hazardous waste status has been conferred on SPL in a number of countries, due to its leachable fluoride and cyanide components and potential to evolve flammable mixtures of ammonia, methane and hydrogen gases [4, 8]. A number of utilisation strategies have been developed for the waste: SPL may be added to cement clinker kilns, to improve firing conditions [9]. It can be partially substituted for fluorite (CaF2) in Arc furnaces for steelmaking [10], or used as an additive in pig iron and rock wool production [11, 12]. The issue with all such employments is that only relatively small amounts of SPL may be used, otherwise process complications ensue [9, 13]. Accordingly, various detoxification systems for SPL are also in use, with the goal of converting the waste to an environmentally-benign form. Most are pyrometallurgical, taking advantage of the high chemical energy value of SPL, which has been reported as ≤ 16 MJ g−1 for first-cut samples [14]. The waste may be combusted [15], or sintered with cement and bauxite [16]. This volatilises a fraction of the SPL fluoride content as HF, which can be captured by a scrubber, and recycled [15, 16]. These however cause the emission of CO2, which must either be captured or released into the atmosphere. The only operational hydrometallurgical process is the low caustic leaching and lime (LCLL) method developed by Rio Tinto Alcan. This has a throughput capacity of 80,000 T year−1 and produces an inert carbon/cement mixture, which can be used as an aggregate for building, and fluorite, which can be reused by smelters [17].

The LCLL process recovers the fraction of fluorides which are water-leached from SPL. Lisbona et al. however, showed that many fluoride compounds remain within the SPL matrix after water-washing [18]. Fluoride is rapidly becoming a scarce resource, as the only major natural reserves are in the form of geological fluorite, of which there are < 35 years-worth remaining globally. Fluorite has been classified as a “critical” mineral by the European Union for future conservation since 2014 [19] and its market price is on a long-term upwards trend [20]. Therefore, there is a clear impetus for a more efficient hydrometallurgical treatment, which will solublise and moreover, recover a greater fraction of the fluoride content of SPL.

A number of different leaching treatments for SPL have been researched. Only a very small number of single-step treatments have been proposed, one using chromic acid as the lixiviant [21]. This reduced the fluoride content in the solid output to < 150 mg kg−1, but an estimated 10–11% alumina (Al2O3) remained in the waste. Al3+ salts, in acidic conditions, have also been favoured as lixiviants [18]. The advantage of this approach is that an aluminium hydroxyfluoride (AHF) hydrate product can be precipitated from the leachate, which may then be converted to AlF3 and recycled directly back into aluminium smelters [22]. However, it has thus far achieved only 76–86% fluoride extraction [23, 24]. Dilute caustic leaching has also been investigated and found to extract 70–90% of the total fluoride content of SPL [25]. More recently, caustic leaching has been enhanced by ultrasonication techniques, as shown by Xiao et al. [26]. This technique has afforded a solid residue of ≤ 94.7% carbon. It should however be noted that the SPL used in this study was first-cut material only and the majority fraction of SPL excavated from decommissioned smelter cells is a mixture of first- and second-cut [18]. It is generally recognised that multi-step leaching is required to reduce the concentrations of fluoride and other contaminants in the solid residue to a level safe to landfill [17, 27]. Shi et al. used leaching conditions of 2.5 M NaOH, then 9.7 M HCl, both at 100 °C, attaining carbon of 96.4% purity [27]. Li et al. achieved a carbon purity of 95.5% after a leaching treatment using first, deionised water and second, acidic aluminium anodizing wastewater [3]. However, the SPL used in the instance was again first-cut in origin. The residual fluoride concentration in the carbon residue was also not reported. Neither previous study addressed the issue of labile cyanide destruction in the leachate. It is arguably necessary, from an environmental and economic perspective, that an optimum treatment system should recover close to 100% of the trapped fluorides within SPL waste. It should furthermore deal effectively with all grades of the waste, rather than a selected fraction.

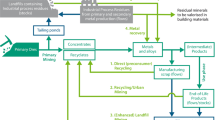

Our research group has conceptualised a treatment system, capable of dealing with all SPL cuts (Fig. 1). It aims to mobilise > 95% of fluoride-bearing contaminants via a two-step leach. The two leachate streams are then combined, whilst ensuring minimal precipitation, producing a liquor of high ionic strength. This however is likely too complex to afford recovery of commodity chemicals of high purity by precipitation. This is seen in the fact that the fluorite currently produced by the LCLL process, which is procured by leaching the SPL with only water, achieves a purity of only 87% [17]. Therefore, an ion-exchange step must be introduced, to immobilise the fluorides selectively upon a solid-phase extractant, allowing potential co-precipitating species to elute. The fluorides are then themselves eluted as an analytically pure and concentrated solution, from which precipitation of pure. A lanthanum-loaded, chelating, weak acid cation-exchange (WAC) resin was chosen for this purpose. The chemical functionality, modification and uptake behaviour has been reported in previous work and is beyond the scope of this study. However, key information is seen in Figures S1–S2. The adsorbent has extracted fluoride from a simulated SPL leachate with an efficiency of 126 mg g−1 via a unique complexation reaction between La centres and aqueous aluminium hydroxyfluorides (AHFs) [28]. It was also observed to load efficiently in simulated industrial conditions using a mini resin column [29]. We were able to elute a solution of aluminium and fluoride ions, relatively free of cocontaminants, from which it was calculated that synthetic cryolite (Na3AlF6) was a viable recovery product. Cryolite is the major component of the Al electrolysis bath. Modern smelter technology has led to improved recycling techniques in recent years, with some sources stating that bulk cryolite purchases are not necessary for the most efficient plants [30]. Nonetheless, the market price of synthetic cryolite is projected to remain high in the medium-term, due to the ever-increasing demand for Al metal, and is consistently higher than that of fluorite.

Hence, the major novelty and improvement of our proposed system over existing technology is that almost all of the SPL fluoride content is valorised, rather than merely a small fraction. It therefore has the potential to not only contribute towards efficient fluoride recycling, but also add economic value to Al smelting operations.

It must be noted however, that the elution behaviour of our column system was not optimised and it is vital to prove that the ion-exchange system performs equivalently in treating actual SPL leachate, as opposed to a simplified simulant solution. This article presents a simple, rapid leaching treatment of mixed-cut SPL, which is often eschewed in favour of the less challenging first-cut fraction. The system is based on the principles of the LCLL process, consisting of first, NaOH/peroxide, then H2SO4 leaching, at mild concentrations and temperatures. We present characterisation of the SPL waste before and after leaching, showing the efficacy of the treatment. The leachates themselves are also characterised in detail, with attention paid to their anionic make-up, which is a feature inadequately documented in the literature so far. Finally, we demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed ion-exchange circuit implementation via column loading and elution studies. These show that resin uptake performance and the quality of the resulting fluoride/Al-rich liquor actually exceeds results achieved previously with a simulant feed and marks a clear step towards realisation of this system industrially.

Experimental

Materials and Reagents

Mixed-cut SPL, of various grades and ages, was kindly provided by Trimet Aluminium (Essen, Germany). All purchased reagents were of analytical grade or better. Deionised water was used throughout. H2SO4 and H2O2 (30% aqueous solution) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. NaOH pellets were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Puromet™ MTS9501 was kindly donated by Purolite and converted into La-loaded form (which will be referred to as La-MTS9501) by the procedure previously reported [28].

Preparation of SPL Prior to Leaching Treatment

The as-received SPL ranged from a fragment size of fine powder to pieces ≤ 5 cm in diameter. The larger pieces were fed into a jaw crusher to be reduced in size. The fractions of each sample were then separated, by sieving, into three grades, these being > 9.51 mm (3/8 inch), 1.18–9.51 mm and < 1.18 mm. Three different samples, which will be designated as A, B and C henceforward, were identified by visual inspection as having significantly different ratios of cementious to carbonaceous material (Figure S3), thus representing reasonable limits of material that could be provided for processing. Previous research has shown that a particle size of ~ 1.18 mm represents the threshold, below which, leaching treatments are generally not more effective [18]. Therefore, the smaller two grades for samples A, B and C were carried forward to the chemical leaching trials.

Solid-State Characterisation of Materials

For powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis, SPL samples, at various process stages, were ground with a mortar and pestle, inside a glove bag. PXRD was performed using a Bruker D2 phaser, with diffractograms matched using the ICDD database [31]. SEM samples were mounted onto aluminium stubs, using carbon tape and were analysed, without any coating treatment, using a Jeol JSM6010 microscope. Quantification of C, H, N and S for leached samples was performed using a Perkin Elmer 2400 CHNS/ 0 Series II Elemental Analyzer.

Leaching Treatment of SPL

All leaching treatments were performed at ambient temperature (~ 20 °C). In a typical caustic leaching experiment, 2.0 g SPL was weighed into a large polypropylene beaker, fitted with a large magnetic stirrer. A 100 mL solution of NaOH at pH 11.0, including 10 mL H2O2 was added and the suspension was stirred at 200 rpm for 3 h. In initial studies, the complete oxidation of cyanide was checked using ion chromatography (IC), which is described in Sect. 2.5. After this time, the NaOH concentration was increased to 1 M and the total volume to 250 mL. Leaching proceeded for a further 3 h, after which the suspension was gravity filtered. The leachate was conserved for analysis and subsequent ion-exchange studies. The solid residue was briefly rinsed with 250 mL water, then dried in an air-flow oven at 50 °C for a minimum of 24 h, before being conserved for future experimentation. In a typical acidic leach, 2.0 g SPL was again weighed into a large polypropylene beaker, with stirrer. To this was added 250 mL 0.5 M H2SO4 and the suspension was stirred at 200 rpm for 3 h. Similar separation procedures to the caustic leach were then used. The solid:liquid ratio was chosen based on the efficiency reported by previous researchers [18, 24] and the aim to match the resulting [F−] and [Al3+] with the simulant leachate used in previous work. The rinsing water used between leaches was analysed for fluoride and cocontaminant concentration. However, levels were found to be insignificant compared to caustic and acidic leachate and this water was not conserved. In some experiments, small “thief” samples (100 μL) of the progressing leachate were removed from the beaker at various time intervals during the leaching, to allow the increasing fluoride concentration to be monitored. The volume of leachate removed did not exceed 1% of the total.

Characterisation and Mixing of Leachates

The majority of elemental quantification was achieved by inductively-coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS), using an Agilent 7500CE spectrometer by diluting samples appropriately in a 1% HNO3 matrix (Trace Select grade). Anions were quantified using a Metrohm 883 Basic IC plus IC system, fitted with a Metrosep A Supp 5-4 × 150 mm column and using Na2CO3/NaHCO3 eluent. Samples were diluted appropriately with deionised water. Fluoride was also quantified by potentiometry, using a Sciquip ion-selective electrode (ISE), using total ionic strength adjustment buffer (TISAB) solution. A number of samples were cross-measured by both methods during data collection and results were consistently in agreement within 2%.

Acidic and basic leachates were combined by pipetting appropriate volumes into polypropylene vials, followed by any necessary pH adjustment, using H2SO4 or NaOH. Any precipitates were collected by vacuum filtration of the suspension through a sintered glass funnel, followed by drying of the solids via air-flow oven as previously described. Precipitates were characterised by PXRD, as previously mentioned. Theoretical aqueous speciation data was determined using the Aqion computer programme [32]. Concentrations of each species were inputted to the programme, according to ICP-MS and IC data. Charge balance was achieved by adjusting either [Na+] or [SO42−].

Fluoride Uptake by La-MTS9501 and Elution in Fixed-Bed Column Studies

La-MTS9501 resin (5.50 mL wet settled volume, 1.79 g dry mass) was packed into a miniature polypropylene column, fitted with porous frits above and below the resin bed. This was connected, as a reverse-flow system, to a Watson Marlow 120U peristaltic pump, using Watson Marlow Marprene® tubing (0.8 mm internal diameter) A photograph of the set-up is shown in the Supporting Information, Figure S4. The system was calibrated over a period of 24 h to give a flow rate of 1.00 bed volume (BV) per hr (BV = an equivalent volume of inlet solution to that of the mass of the resin bed). The combined leachates were thus passed through the resin column. Eluent was collected in 0.5 BV fractions and analysed for fluoride concentration, via ISE. A number of common dynamic breakthrough models were used to attempt to describe the data (Supporting Information, p3). For elution experiments, the loaded resin bed was connected, as before, to an inlet stream of deionised water, followed by 1 M NaOH. Eluent was collected and analysed for fluoride concentration as before. Certain fractions were also analysed for Al and selected other elements, via ICP-MS and IC, as previously described. The % recovery of fluoride from the inlet leachate was estimated by calculating the area under the major fluoride elution peak and dividing this by the theoretical uptake capacity of the column, determined from dynamic model-fitting.

Results and Discussion

Solid-State Characterisation

The elemental analysis results for the full range of samples and size fractions is presented in Table 1.

From the elemental composition of the leached samples, it is seen that the C % of the SPL increases for mixed-cut and mainly first-cut samples, following the acidic leach, as more contaminants are solublised. The H % also decreases significantly for most samples between the leaching treatments, which may suggest the original material contained an organic hydrocarbon component, which dissolves during the treatment (also suggested in PXRD spectra by the amorphous region). The N % is very inconsistent across all samples and the S % actually increases slightly, following the acidic leach, which is likely due to residual SO42− not entirely removed by the final water wash. Notably, the C % was always greater in the smaller size fraction, across all samples, but the difference was only consistently very large in the case of sample B. It would not be possible, for example, to separate the carbonaceous and cementious fractions effectively on this basis. The attained carbon purity for our first-cut samples is slightly lower that reported in some previous work (> 90%) [3, 27]. However, since the proposed treatment is designed for mixed-cut SPL, this parameter is of lesser significance. The separation of first-, second- and mixed-cut SPL is a crude process, employing pneumatic hammers to break up the material [33]. Therefore, the quality of separation varies, depending on the individual smelter.

The attained PXRD diffractograms, as expected, showed a large variety of crystalline species in the untreated SPL samples and substantial variation in the amount of mineral contamination between the three samples, relative to their graphitic content (Fig. 2). In the mixed-cut samples, there was also an amorphous component, which is believed to be closely related to NaAlSi3O8 (albite) [34]. After the caustic leaching treatment, some crystalline species were absent or obviously reduced in concentration in the diffractograms, but only the full leaching process returned diffractograms that showed principally graphite and only trace levels of contaminants. The effect of the leaching treatment is shown in Fig. 2. The full array of diffractograms may be seen in Figures S9–S22.

Compared to previous SPL characterisation attempts, sample C appeared to be relatively free of contamination, with NaF being the only significant species present, apart from graphite. Li et al. reported a similar XRD spectrum for, first-cut SPL, to Fig. 2c [3]. Other researchers have reported high levels of alumina (Al2O3), fluorite, cryolite and diaoyudaoite in first-cut material [18, 27]. There have been few attempts to characterise second- or mixed-cut SPL by PXRD, with the exception of Tschope et al. [35], who did not find evidence of sodium carbonate hydrate or silicon carbide (SiC). However, the species observed in this instance are predictable, given the known components of a smelting cell. Portland cement and fire brick would be expected to contain a large SiO2 component [36], whilst the sidewall bricks of a smelting cell can made entirely of SiC, depending on design [37].

Selected SEM data is seen in Fig. 3. Again, the full set of micrographs may be viewed in the Supporting Information, S23–S25. The elemental composition of the material, determined by point EDX analysis in the regions denoted with Greek symbols, is shown in Table 2.

Figure 3a confirms that a large fraction of second-cut material was present in sample A. The accompanying EDX mapping (Fig. 3b) suggested that the distribution of fluorides within the material, at the microscale, was strongly heterogenous. The visible crystalline precipitation in Fig. 3c appeared to be NaF, according to elemental composition (Table 2) and was unsurprisingly absent following the leaching treatment (Fig. 2d). Needle-like formations of NaF crystals have previously been reported from investigations of exhausted smelter cells [34].

Leachate Characterisation

Table 3 shows the quantities of major chemical species that were mobilised by the two leaching treatments. Data for the more minor contaminants are shown in Table S1.

The data suggested there was no increase in leaching efficiency between the two size fractions, which would be advantageous industrially, as coarser grinding of the SPL would require less energy input. The approximate composition of the SPL material, derived from the leaching data can be compared to values quoted by Holywell and Bréault [1] (Table S3), which is often referenced in the literature as being an accurate range [28, 38]. The apparent concentrations of Al Fe, Ti and Mg were considerably lower than expected, although it should be noted that our values are based on the total leachable content under the conditions stated and should not be considered total quantification values. For example, the Ca and Fe content of the SPL was mainly solublised by the second acidic leach, but the values in Table 3 do not reflect the mass fractions in the original SPL, because a large mass % is solublised in the first caustic leach. Nonetheless, because nearly all fluoride is solublised in the initial caustic leach, these values are roughly comparable to the literature. It can be seen that the total amount of fluoride in this SPL is lower than has been reported for previous samples. Lisbona et al. analysed samples from a now disused smelted in the United Kingdom and found the fluoride concentration to be > 19% [18]. Xiao et al. reported a concentration of ~ 13% in a sample sourced from China [26]. These examples however, were both first-cut only material, in which the fluoride and Na content is markedly higher [1]. Given the relatively low fluoride and cyanide contamination identified in this report, it is likely that the original cells were of prebake, rather than Söderberg design [1].

As expected, the majority fraction of the SPL fluoride content was mobilised by the caustic leach [25]. This would have included most of the NaF originally present, which previous studies, and indeed the LCLL process, have shown to be mainly removed by washing with water [3, 17]. Our work however, shows that both caustic and acidic leaching conditions decrease the quantity of NaF within the solid material (this is seen for example, in Figures S11–S13). NaF is highly water soluble (~ 4 g L−1 at ambient temperature), hence it is likely that the different lixiviants solublise different fractions of the SPL matrix, allowing the leaching solution to access further trapped NaF crystals. NaF was only observed in large quantities in sample C, with most fluoride in the other two received samples being more complex species (Fig. 2a). The other main SPL contaminants soluble in base are cryolite and alumina. The latter was surprisingly not detected in this study, although it is not always present in SPL samples [34]. Major contaminants diaoyudaoite and fluorite, in contrast, are only soluble in acidic conditions. This is seen most clearly in Figure S12.

Although the quantity of fluoride mobilised by the acid leach was, on average, ~ 20 times less than by the basic leach, it is a necessary step to reduce the fluoride concentration in the residual solid to a level that would allow classification as non-hazardous waste. There are a range of national and international classifications for solid waste-forms, which govern the level of control required with respect to landfill disposal. This paper will refer throughout to criteria used by the European Union (Council Decision annex 2003/33/EC) [39]. It can be seen from Table 3 that the caustic leaching treatment also does not fully solublise a number of hazardous metals. Considering an average across all samples studied, the SPL, post-caustic leaching, would contain potentially leachable quantities of fluoride (> 4,000 mg kg−1) and selected fraction would contain 295 mg kg−1 Cu, 90 mg kg−1 Cr and 46 mg kg−1 Ni. All of these figures are in excess of the EU maximum allowable levels for ‘landfilled hazardous waste’, these being 50, 100, 70 and 40 mg kg−1 respectively [39]. This demonstrates the necessity of the acidic leach. This research group plans to conduct future trials on the residual barren SPL samples, after both leaches, to determine leachability of remaining contaminants.

Any labile cyanide originally in the samples was oxidised to cyanate via the initial peroxide treatment, then caustic leachate samples were checked, during IC analysis, for the presence of a cyanate peak. This peak was not detectable above baseline for any of the samples analysed, at a dilution factor of 10. It can therefore be assumed that the great majority of cyanide present in this particular source of SPL was converted to ferrocyanides or ferricyanides, most likely Na4Fe(CN)6 and Na3Fe(CN)6, which is known to occur when the waste is exposed to the environment over time [40]. These species may ultimately end up in the ion-exchange circuit and specifically, the wastewater from the fluoride and Al elution process. This water would also contain other toxic species and its potential treatment has been discussed in previous work [29]. However, there is an existing ferro- and ferricyanide-removal process in the LCLL system, which would be implemented before the ion-exchange step [17].

The anionic composition of the leachates is of particular interest compared to our previous studies, with respect to competition and suppression effects on the uptake of fluoride during the ion-exchange treatment. We predicted a greater NO3− concentration, but under-predicted the SO42− concentration [29]. This was partially due to considering only the contribution from the acid lixiviant, rather than this and the contribution from the material itself [41]. SO42− has only weak affinity for Al3+, but at such high concentrations, AlSO4+ and Al(SO4)2− are predicted to form [32] and this could partially suppress the formation of aqueous aluminium fluorides, hence interfering with the resin uptake mechanism.

The progression of the leaching treatment over time was determined by quantification of fluoride in the leachate at various time intervals, during leaching of sample B, 1.18–9.51 mm (Fig. 4). This sample was so chosen, due to having large carbonaceous and cementious components. It can be seen that the largest fraction of fluoride, most likely principally in the form of NaF, is rapidly solublised by the dilute NaOH /H2O2 solution. This is unsurprising, given the high level of solublisation reported via water-washing of SPL [24], which can essentially be attributed to the presence of ammonia, sodium carbonate hydrate and other basic species [42], which cause fairly alkaline leaching conditions in-situ. Upon increasing the NaOH concentration to 1 M, solublisation continues more slowly and reaches equilibrium in a total of ~ 6 h. Nonetheless, it is clear that significant extra fluoride is mobilised by the increase in base concentration, which confirms that water-washing alone does not lead to full fluoride extraction for mixed-cut SPL. This is in agreement with previous work, focussed on only first-cut SPL [18, 24]. The acidic leaching is more rapid, reaching equilibrium in ~ 2 h.

In terms of the timescale required for effective leaching, this treatment is Comparable to most literature procedures (Table S2). The alkaline H2O2 pre-leaching cyanide-oxidation step could possibly be shortened to improve efficiency, but because of the complete absence of labile cyanide in these samples, this could not be assessed. One advantage of this treatment is that it operates at ambient temperature, whereas most studies have performed leaching at elevated temperature, finding the efficiency to be improved [21, 27]. A comparison of laboratory-scale leaching treatments (Table S2) illustrates that our proposed treatment uses much higher dilutions of lixiviants than has been previously attempted [27]. Temperature was not considered as a variable in this work, as the uptake capacity of La-MTS9501 decreases at elevated temperature [29]. Hence it would be more practical industrially for both the leaching and ion-exchange sides of the process to operate at ambient temperature.

The variability of key chemical species concentrations within the range of samples appears to be very high, which is rarely discussed in previous studies. This reinforces the need for the proposed ion-exchange system to handle an inlet stream of variable composition.

Combination of Leachates and Resulting Precipitates

Parameters from the theoretical mixing of caustic and acidic leachates for selected samples and fraction sizes were inputted into the Aqion modelling software. Sample A, < 1.18 mm and sample A, 1.18–9.51 mm were chosen, as they represented the limits for the sample range studied, with respect to the F−:Al3+ molar ratio in the final mixed leachate. For sample A, < 1.18 mm, this was 1.54 and for sample A 1.18–9.51 mm, it was 7.66. This choice was made because our previous work suggested that the performance of the La-MTS9501 resin was sensitive to this parameter [29]. We also acquired data for sample C, 1.18–9.51 mm, to compare first-cut with mixed-cut leachates. We finally calculated a theoretical average that would be produced by mixing the leachates from all samples and size fractions together. Previous ion-exchange experiments, using synthetic leachate, were run at pH 5.5. However, Aqion predicted substantial precipitation of SiO2 and CaF2 under these conditions, which experimental observations, at small scale, appeared to confirm. Therefore, pH was adjusted to 3.0 to minimise any precipitation. Our equilibrium work suggested this would result in a minimal decrease in resin performance [28].

The aqueous speciation results are presented in Table 4. For brevity, only major F, Al and S species are shown. It should also be noted that Aqion does not account for Ba, Be, Li, Ti, V, Y and Zr, which would all have been present in the mixed leachates. The associated concentrations would be < 10 mg L−1, meaning any significant interference in fluoride or Al uptake behaviour would be minimal.

Table 4 shows that, at both the lower and upper limit of the F−:Al3+ ratio, the dominant fluoride-bearing species is an Al complex, due to the well-known mutual affinity of the two species [43]. This was also the case for the simulant leachate used in previous ion-exchange experiment, which produced excellent resin uptake performance [29]. The real leachates possess greater relative concentrations of AlF2+ and AlF3, rather than AlF2+. This may be advantageous to resin efficiency, assuming the main complexation reaction involves stoichiometric binding of one AHF with one La centre on the resin surface, as this would lead to the loaded resin being more fluoride-rich (Figure S2). It can also be seen that some leachates contain significant concentrations of free aqueous fluoride and HF. We had not previously examined a system with these species and aluminium fluoride complexes co-existing and the effect on uptake behaviour was unknown at this point.

It was found that the most efficient way to combine the two leachate streams was to cautiously add caustic leachate to acidic, whilst maintaining pH below 3.5, to minimise precipitation. The masses of precipitates attained were recorded and are shown in Table S4. The amount of precipitation generally increased with the fraction of second-cut material in the sample. PXRD spectra of selected precipitates from all three samples were examined, namely sample A, 1.18–9.51 mm, sample B, < 1.18 mm and sample C < 1.18 mm (Figures S29–S32). The only identifiable crystalline component in the spectra was cryolite. There was also an amorphous component, most likely albite and colloidal silica [34, 44], which varied in size between samples, being much lesser for sample C (mainly first-cut). The purity of the cryolite was thus unlikely to be acceptable for resale as a chemical commodity.

A small amount of precipitation appears to be inevitable, upon mixing the caustic and acidic leachates. It would not be feasible to treat acidic and caustic streams individually with La-MTS9501 resin, as it is completely ineffective at extreme pHs [28]. However, it is desirable to avoid loss of fluoride from the leachate by precipitation of impure cryolite, before it enters the ion-exchange system. There are two potential strategies to negate this. First, the F−/Al3+ ratio could be kept relatively low via addition of aqueous Al3+ salts. Anodizing wastewater would be a potential cost-effective candidate for this application [3, 24]. This however, would require monitoring and quantification techniques performed on both leachate streams before mixing [29, 45]. The second strategy would simply be to redissolve the precipitate in the acid leaching vessel, in-lieu of a small quantity of SPL, as suggested in the flow diagram in Fig. 1.

La-MTS9501 Column-Loading Behaviour

Full breakthrough profiles were attained for column-loading treatment of combined leachates from sample A < 1.18 mm and sample A 1.18–9.51 mm (these again being chosen for representing the extremes of the F−/Al3+ molar ratio). The breakthrough behaviour was generally best-modelled as a pair of individual breakthrough curves, seemingly describing two discreet breakthrough stages, though occurring in quick succession. The first breakthrough “plateau” was determined to have been reached after three BVs were analysed, where the fluoride concentration did not vary by > 1%. Modelling of the second breakthrough curve was started immediately after this. Column data are shown for sample A < 1.18 mm in Fig. 5 (data for sample A 1.18–9.51 mm shown in Supporting Information, p15-16). Parameters for model-fitting are shown in Table S5.

Fluoride breakthrough behaviour via loading of La-MTS9501 resin column from combined leachate of SPL sample A, < 1.18 mm size fraction: a raw data, b modelling of first breakthrough region, c modelling of second breakthrough region. Column volume = 5.50 mL. Resin mass = 1.792 g. Flow rate = 0.50 BV hr−1. T = 20 °C. Error bars represent 95% confidence limits, derived from 3 replicate electrode measurements

The Dose–Response model provided the most accurate modelling of the two breakthrough regions (Table S5). This model has previously been observed to minimise the errors produced by other breakthrough models [29, 46]. The resulting maximum dynamic uptake capacity values (q0, in units of mg g−1) were therefore considered the most valid to compare the different experiments. These values for sample A < 1.18 mm were 5.01 ± 0.11 and 26.7 ± 0.4 mg g−1 respectively for each breakthrough region. For sample A 1.18–9.51 mm, they were 4.23 ± 0.07 and 33.4 ± 0.7 mg g−1. The leachate of sample A < 1.18 mm had a significantly greater inlet fluoride concentration (434 mg L−1, compared to 275 mg L−1). Previous work with simulant leachate showed that the q0 parameter is strongly influenced by this variable [29], so the difference in resin uptake performance is not as great as would be expected. This is especially surprising, given the differences in F−/Al3+ ratio and speciation (Table 3). Our previous kinetic work however, suggested that, as the uptake process approaches equilibrium, ligand-exchange reactions occur with the surface-bound AHFs (Figure S2). This causes some release of fluoride back into solution and leads to the dominant adsorbed species tending towards Al(OH)2F, [29]. This may explain the similar resin performance over the two experiments.

Our previous work also provided strong evidence that the uptake of AHFs by La-MTS9501 is heterogenous, with an initial chemisorption complexation between La centres and aqueous AHFs, followed by a secondary uptake where further AHFs bind to the existing complexation through much weaker interactions, again involving F or O bridging ligands (Figure S2) [28, 29]. This would explain the two discrete breakthrough regions, the first representing the full saturation of the La centres, while the secondary adsorption is still proceeding; the second representing full breakthrough for both adsorption mechanisms. In previous work, using simulant leachate, there was not significant evidence of a two-stage breakthrough process [29]. However, the ionic strength of the inlet was much greater in this work (554 and 605 mmol L−1 in these experiments verses 24.8 mmol L−1 for the simulant leachate), which is likely to have retarded the adsorption kinetics [47].

Overall, the efficiency of the resin, using SPL leachate, compares well to data produced using a simulant feed and otherwise similar conditions. This produced a q0 value of 66.7 ± 9.1 mg g−1, with the inlet fluoride concentration being substantially higher (1500 mg L−1) [29]. It can be concluded that the more complex chemistry and higher ionic strength of the real leachate is not detrimental to resin performance.

La-MTS9501 Column-Elution Behaviour

Elution of the column proceeded first with deionised water, which displaced the residual leachate and also removed the majority of weakly-bound cocontaminant ions. Figure 6 shows that this process was complete after ~ 35 BV. Previously, in experiments with synthetic leachate, we then switched the eluent to 0.01 M NaOH. This resulted in a fairly pure stream of fluoride and Al, but at unsatisfactory concentrations unsuitable for cryolite recovery [29]. In this work, we immediately switched to 1 M NaOH, with the result being sharp fluoride and Al elution peaks at almost identical retention times. Furthermore, the averaged concentrations of fluoride and Al for the relevant eluent fractions was 658 ± 18 mg L−1 and 807 ± 30 mg L−1 respectively (34.6 ± 0.9 mmol L−1 and 29.9 ± 0.6 mmol L−1). This appears to support the hypothesis that the dominant resin-bound species has an approximate 1:1 F−/Al3+ molar ratio [29]. To assess the purity of the eluent stream, these fractions were also analysed for all of the cocontaminants present in Table 3, again by ICP-MS or IC. The great majority of species were below detectable limits. Those present in significant quantities are shown in Table 5.

The substantial presence of SO42− and PO43− can be attributed to deprotonation of the secondary amine in the MTS-9501 functional group [29]. This would preferentially bind SO42− and PO43− from the leachate during column-loading, due to the high affinity of these two anions for amine functionalities [48]. Neither anion would be expected to be deleterious to cryolite precipitation. In fact, Na2SO4 may be used to add to acidic F−/Al3+ solutions to induce cryolite precipitation [49]. The most problematic species in the solution is likely to be Si, which could feasibly coprecipitate as SiO2 over the working range for cryolite recovery [32], or form polymeric silica colloids [44]. However, there are recognised economical commercial methods for silicon removal from aqueous circuits if necessary, such as the inorganic salt SilStop® [44]. The LCLL process, in fact, already implements a Si removal step from acidic leachate [1]. A key consideration for the proposed process is whether the F−/Al3+ molar ratio produced is appropriate for cryolite precipitation. The literature is somewhat diverse on this point. Chen et al. reported that, at a 1:1 ratio, aluminium hydroxyfluoride precipitation dominates over cryolite, although only at pH 5.5 [49], whereas Jiang and Zhou predicted favourable cryolite recovery at the same ratio at pH 9 [50] and Wang et al. demonstrated success using a F−/Al3+ molar ratio of ~ 1:2.55 (although this was achieved by neutralisation of an acidic starting solution) [51]. We have considered the molar ratio monitoring and potential adjustment in previous work [29]. It is notable that, in the initial elution from the column with deionised water, [F−] greatly exceeds [Al3+] and this fraction could potentially be recycled and used for ratio control of the inlet stream, but detailed precipitation studies and optimisation are clearly called for as a next step of the process development. Overall however, the inlet leachate, has been not only purified, but enriched in fluoride. The calculated recovery, derived from the Dose–Response model q0 parameter, was 59.0% and, as mentioned, the initial water wash eluent could potentially be re-treated to further maximise recovery. The quantity of water used also decreased greatly, relative to previous work, from 2500 to 600 mL for elution of a 5.5 mL column [29].

Conclusions

A simple leaching treatment for spent potlining (SPL) has been developed, with a view to valorisation of the waste, via fluoride and aluminium uptake in an ion-exchange column system, using chemically-modified La-MTS9501 resin. The leaching employs economical lixiviants (NaOH/H2O2, then H2SO4) at high dilutions, works at ambient temperature and is effective for a variety of SPL grades. First-cut and mixed-cut SPL samples, of two different size fractions, were subjected to both stages of the leaching treatment. The SPL was characterised by PXRD and SEM, which confirmed both the strongly heterogeneous nature of the material and the effectiveness of the leaching in terms of mobilising the contaminants. The leaching produced a variety of liquors, which were characterised by ICP-MS and IC, again revealing large differences in elemental composition. Caustic and acidic leachates were combined and pumped through an ion-exchange column to assess the performance of La-MTS9501 with a real industrial leachate feed. The resin performed similarly well in the uptake of fluoride from two inlet solutions of substantially different composition. Dynamic maximum uptake values were in excess of 30 mg g−1 in both cases. The loaded fluoride and aluminium could be coeluted, using 1 M NaOH, with minimal cocontaminants, producing an enriched, alkaline solution, with a minimum 59.0% recovery, which will now be taken forward to cryolite precipitation studies. This work confirmed the high selectivity of the resin for uptake of aluminium hydroxyfluorides in a complex industrial liquor of high ionic strength and demonstrated improved process efficiency.

References

Holywell, G., Bréault, R.: An overview of useful methods to treat, recover, or recycle spent potlining. J. Miner. Met. Mater. Soc. 65, 1441–1451 (2013)

Sleap, S.B., Turner, B.D., Sloan, S.W.: Kinetics of fluoride removal from spent pot liner leachate (SPLL) contaminated groundwater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 3, 2580–2587 (2015)

Li, X.M., Yin, W.D., Fang, Z., Liu, Q.H., Cui, Y.R., Zhao, J.X., Jia, H.: Recovery of carbon and valuable components from spent pot lining by leaching with acidic aluminum anodizing wastewaters. Metall Mater. Trans. B 50, 914–923 (2019)

Suss, A., Kuznetzova, N., Damaskin, A., Paromova, I., Panov, A.: Issues of spent carbon potlining processing. The International Committee for Study of Bauxite, Alumina & Aluminium, United Arab Emirates (2015)

Pawlek, R.: Spent Potlining: An Update. In: Suarez, C.E. (ed.) Light Metals 2012, pp. 1313–1317. Wiley, Hoboken (2012)

International Aluminium Institute: Primary Aluminium Production. https://www.world-aluminium.org/statistics/ (2019). Accessed 20 Apr 2019

Yu, D., Mambakkam, V., Rivera, A.H., Li, D., Chattopadhyay, K.: Spent Potlining (SPL): A myriad of opportunities. Alum. Int. Today Sept. 17–20 (2015)

European Union.: Council Directive of 12 December 1991 on hazardous waste (91/689/EEC). Off. J. Eur. Commun L 377, 20–27 (1991)

Miksa, D., Homsak, M., Samec, N.: Spent potlining utilisation possibilities. Waste Manag Res. 21, 467–473 (2003)

Deshpande, K.G.: Use of spent potlining from the aluminium electrolytic cell as an additive to arc furnace steel melting and cupola iron melting in steel industries. Environ. Waste Manag. 831, 129–136 (1998)

Olsen, F.: Elkem spent potlining recycling project. Waste Treatment and Clean Technology. Warrendale, Pensylvania, REWAS Global Symposium on Recycling (2008)

Breivik, Ø.: From waste to resource. Norsk Hydro, Oslo (2013)

Gao, L., Mostaghel, S., Ray, S., Chattopadyay, K.: Using SPL (spent pot-lining) as an alternative fuel in metallurgical furnaces. Metall. Mater. Trans. E 3E, 179–188 (2016)

Cardoso, A.B.: Spent potliner management in primary aluminium production. 62nd ABM International Annual Congress. Vitoria, Brazil (2007)

Hopkins, T., Merline, P.: Comtor process for treatment of spent potlining. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 15, 247–255 (1995)

Bazhin, V.Y., Patrin, R.K.: Modern methods of recycling spent potlinings from electrolysis baths used in aluminium production. Refract. Ind. Ceram. 52, 63–65 (2011)

Birry, L., LeClerc, S., Poirier, S.: The LCL&L process: A sustainable solution for the treatment and recycling of spent potlining. In: Williams, E. (Ed.) Light Metals 2016, pp. 467–471 (2016)

Lisbona, D., Somerfield, C., Steel, K.: Leaching of spent pot-lining with aluminium nitrate and nitric acid: Effect of reaction conditions and thermodynamic modelling of solution speciation. Hydrometall. 134, 132–143 (2013)

European Commission: Communication from The Commission to The European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of The Regions. On the 2017 list of Critical Raw Materials for the EU. European Union, Brussels (2017)

Roskill: Fluorspar. Global Industry, Markets and Outlook 2018. Roskill Information Services, Wimbledon (2018)

Mazumder, B.: Chemical oxidation of spent cathode carbon blocks of aluminium smelter plants for removal of contaminants and recovery of graphite value. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 62, 1181–1183 (2003)

Ntuk, U., Tait, S., White, E.T., Steel, K.M.: The precipitation and solubility of aluminium hydroxyfluoride hydrate between 30 and 70 degrees C. Hydrometall. 155, 79–87 (2015)

Lisbona, D.F., Steel, K.M.: Recovery of fluoride values from spent pot-lining: Precipitation of an aluminium hydroxyfluoride hydrate product. Sep. Purif. Technol. 61, 182–192 (2008)

Lisbona, D.F., Somerfield, C., Steel, K.M.: Leaching of spent pot-lining with aluminum anodizing wastewaters: Fluoride extraction and thermodynamic modeling of aqueous speciation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 8366–8377 (2012)

Silveira, B.I., Dantas, A.E., Blasquez, J.E., Santos, R.K.P.: Characterization of inorganic fraction of spent potliners: evaluation of the cyanides and fluorides content. J. Hazard. Mater. 89, 177–183 (2002)

Xiao, J., Yuan, J., Tian, Z.L., Yang, K., Yao, Z., Yu, B.L., Zhang, L.Y.: Comparison of ultrasound-assisted and traditional caustic leaching of spent cathode carbon (SCC) from aluminum electrolysis. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 40, 21–29 (2018)

Shi, Z.-N., Li, W., Hu, X.-W., Ren, B.-J., Gao, B.-L., Wang, Z.-W.: Recovery of carbon and cryolite from spent pot lining of aluminium reduction cells by chemical leaching. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 22, 222–227 (2012)

Robshaw, T.J., Tukra, S., Hammond, D.B., Leggett, G.J., Ogden, M.D.: Highly efficient fluoride extraction from simulant leachate of spent potlining via La-loaded chelating resin. An equilibrium study. J. Hazard. Mater. 361, 200–209 (2019)

Robshaw, T.J., Dawson, R., Bonser, K., Ogden, M.D.: Towards the implementation of an ion-exchange system for recovery of fluoride commodity chemicals. Kinetic and dynamic studies. Chem. Eng. J. 367, 149–159 (2019)

Kvande, H.: Production of Primary Aluminium. In: Lumley, R. (Ed.) Fundamentals of aluminium metallurgy; production, processing and applications. Woodhead Books, Sawston, Cambridge (2011)

Fawcett, T.G., Needham, F., Crowder, C., Kabekkodu, S.: Advanced materials analysis using the powder diffraction file. 10th National Conference on X-ray Diffraction and ICDD Workshop. Shanghai, China (2009)

Kalka, H.: Aqion: Manual (selected topics). https://www.aqion.de/site/98? (2015). Accessed 20 April 2019

Tschope, K.: Degradation of cathode lining in Hall-Heroult cells. PhD thesis. Materials Science and Engineering, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim (2010)

Tschope, K., Schøning, C., Rutlin, J., Grande, T.: Chemical degradation of cathode linings in Hall-Heroult cells—An autopsy study of three spent pot linings. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 43B, 290–301 (2012)

Tschope, K., Store, A., Solheim, A., Skybakmoen, E., Grande, T., Ratvik, A.P.: Electrochemical wear of carbon cathodes in electrowinning of aluminum. J. Met. 65, 1403–1410 (2013)

Afshinnia, K., Poursaee, A.: The potential of ground clay brick to mitigate alkali-silica reaction in mortar prepared with highly reactive aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 95, 164–170 (2015)

Yurkov, A.: Refractories For Aluminium. Springer, Switzerland (2015)

The Council of the European Union: Council decision of 19 December 2002, establishing criteria and procedures for the acceptance of waste at landfills pursuant to Article 16 of and Annex II to Directive 1999/31/EC (2003/33/EC). Official J. European Communities L11, 27–49 (2003)

Courbariaux, Y., Chaouki, J., Guy, C.: Update on spent potliners treatments: Kinetics of cyanides destruction at high temperature. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 43, 5828–5837 (2004)

Ospina, G., Hassan, M.I.: Spent pot lining characterization framework. J. Met. 69, 1639–1645 (2017)

Pong, T.K., Adrien, R.J., Besida, J., O'Donnell, T.A., Wood, D.G.: Spent potlining - A hazardous waste made safe. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 78, 204–208 (2000)

Cooper, B.: Applying industrial ecology to address environmental concerns associated with aluminum smelter spent potlining. In: 66th Annual technical meeting of the indian institute of metals, Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India (2012)

Strunecka, A., Strunecky, O., Patocka, J.: Fluoride plus aluminum: Useful tools in laboratory investigations, but messengers of false information. Physiol. Res. 51, 557–564 (2002)

Sole, K.C., Crundwell, F.K., Dlamini, N., Kruger, G.: Mitigating effects of silica in copper solvent extraction. 9th Southern African Base Metals Conference, Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Livingstone, Zambia (2018)

Hanson, T.J., Smetana, K.M.: Determination of aluminium by four analytical methods. Atlantic Richfield Hanford Company, Richland, Washington (1975)

Yan, G.Y., Viraraghavan, T., Chen, M.: A new model for heavy metal removal in a biosorption column. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 19, 25–43 (2001)

Moreira, M.J., Ferreira, L.M.: Kinetic studies for sorption of amino acids using a strong anion-exchange resin. Effect of ionic strength. J. Chromatogr. A 1092, 101–106 (2005)

Helfferich, F.G.: Ion Exchange. McGraw-Hill, New York (1962)

Chen, J.Y., Lin, C.W., Lin, P.H., Li, C.W., Liang, Y.M., Liu, J.C., Chen, S.S.: Fluoride recovery from spent fluoride etching solution through crystallization of Na3AlF6 (synthetic cryolite). Sep. Purif. Technol. 137, 53–58 (2014)

Jiang, K., Zhou, K.: Recovery of cryolite with high molar ratio from high fluorine-containing wastewater. Euro-Mediterranean J. Environ. Integr. 2, 22 (2017)

Wang, L.S., Wang, C.M., Yu, Y., Huang, X.W., Long, Z.Q., Hou, Y.K., Cui, D.L.: Recovery of fluorine from bastnasite as synthetic cryolite by-product. J. Hazard. Mater. 209, 77–83 (2012)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mr Neil Bramall and Ms Heather Grievson (University of Sheffield, Dept. Chemistry) for ICP-MS and elemental analysis respectively. This work was jointly financed by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (Grant no. EP/L016281/1) and Bawtry Carbon International. TJR also thanks the Royal Society of Chemistry, Environmental Chemistry Group for support in presenting this work internationally.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Robshaw, T.J., Bonser, K., Coxhill, G. et al. Development of a Combined Leaching and Ion-Exchange System for Valorisation of Spent Potlining Waste. Waste Biomass Valor 11, 5467–5481 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-020-00954-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-020-00954-1