Abstract

Purpose

A discordance, predominantly towards overtreatment, exists between patients’ expressed preferences for life-sustaining interventions and those documented at hospital admission. This quality improvement study sought to assess this discordance at our institution. Secondary objectives were to explore if internal medicine (IM) teams could identify patients who might benefit from further conversations and if the discordance can be reconciled in real-time.

Methods

Two registered nurses were incorporated into IM teams at a tertiary hospital to conduct resuscitation preference conversations with inpatients either specifically referred to them (group I, n = 165) or randomly selected (group II, n = 164) from 1 August 2016 to 31 August 2018. Resuscitation preferences were documented and communicated to teams prompting revised resuscitation orders where appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine potential risk factors for discordance.

Results

Three hundred and twenty-nine patients were evaluated with a mean (standard deviation) age of 80 (12) and Charlson Comorbidity Index Score of 6.8 (2.6). Discordance was identified in 63/165 (38%) and 27/164 (16%) patients in groups I and II respectively. 42/194 patients (21%) did not want cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and 15/36 (41%) did not prefer intensive care unit (ICU) admission, despite these having been indicated in their initial preferences. 93% (84/90) of patients with discordance preferred de-escalation of care. Discordance was reconciled in 77% (69/90) of patients.

Conclusion

Hospitalized patients may have preferences documented for CPR and ICU interventions contrary to their preferences. Trained nurses can identify inpatients who would benefit from further in-depth resuscitation preference conversations. Once identified, discordance can be reconciled during the index admission.

Résumé

Objectif

Il existe une discordance, qui tend surtout vers un sur-traitement, entre les préférences exprimées par les patients pour les interventions de maintien de la vie et celles documentées lors de l’admission à l’hôpital. Cette étude d’amélioration de la qualité avait pour objectif d’évaluer cette discordance au sein de notre institution. Les objectifs secondaires de notre étude étaient d’explorer la possibilité que les équipes de médecine interne (MI) identifient les patients qui pourraient bénéficier de conversations approfondies et de voir si la discordance pouvait être corrigée en temps réel.

Méthode

Deux infirmières ont intégré des équipes de MI dans un hôpital tertiaire pour discuter avec les patients hospitalisés de leurs préférences en matière de réanimation entre le 1er août 2016 et le 31 août 2018; les patients leur étaient soit spécifiquement référés (groupe I, n = 165), ou sélectionnés au hasard (groupe II, n = 164). Les préférences en matière de réanimation ont été documentées et communiquées aux équipes, entraînant une révision des ordonnances de réanimation, le cas échéant. La régression logistique multivariée a été utilisée afin de déterminer les facteurs de risque potentiels de discordance.

Résultats

Trois cent vingt-neuf patients ont été évalués, d’un âge moyen (écart type) de 80 ans (12) et avec un score de 6,8 (2,6) à l’Indice de comorbidité de Charlson. Une discordance a été identifiée chez 63/165 (38 %) et 27/164 (16 %) patients dans les groupes I et II, respectivement. Au total, 42/194 patients (21 %) ne souhaitaient pas de réanimation cardiorespiratoire (RCR) et 15/36 (41 %) préféraient ne pas être admis à l’unité de soins intensifs (USI), malgré une mention dans leurs préférences initiales. Parmi les patients chez lesquels une discordance a été notée, 93 % (84/90) ont préféré une désescalade des soins. La discordance a pu être corrigée pour 77 % (69/90) des patients.

Conclusion

La documentation des patients hospitalisés pourrait indiquer des préférences pour des interventions de RCR et d’admission à l’USI contraires aux véritables préférences. Des infirmières formées à cet effet peuvent identifier les patients hospitalisés qui bénéficieraient d’une conversation approfondie sur leurs préférences en matière de réanimation. Une fois identifiée, une discordance peut être corrigée lors de l’admission initiale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Elicitation and documentation of resuscitation preferences for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and intensive care unit (ICU) admission at the time of hospital admission is standard practice in North America.1 These conversations may not be repeated until a subsequent admission or crisis. Frequently, the resuscitation order has no accompanying narrative documentation outlining the rationale for the choice.2,3 Recent reports suggest that elicitation and documentation of patients’ resuscitation preferences are frequently inadequate and often incorrect.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 In the majority of cases, discordance trends towards potential overtreatment with life-sustaining interventions in the ICU.4,5,6,9,10,11,12,13 In one Canadian study, estimates of potential overtreatment ranged across hospitals from 14% to as high as 82%.5 This discordance between patients’ expressed and documented preferences can place patients in vulnerable positions. On the one hand, those who prefer less aggressive care may be at risk of receiving unwanted, intrusive, and costly interventions in the ICU. On the other hand, others may receive less care than they would prefer. Both scenarios have been described as a ‘medical error’5 and efforts are urgently needed to reduce its occurrence.

Intervening around discordance requires that patients at risk be prospectively identified by their healthcare teams. To date, research on discordance has largely focused on documenting this error through surveys and structured questionnaires4,5,6,12 or through retrospective data collection7,9,11,13,14 rather than face-to-face conversations, further limiting the possibility of intervening in real-time. Thus, we hypothesized that trained and dedicated registered nurses (RN) could confirm the prevalence and nature of discordance and help the healthcare teams conduct further timely conversations to resolve it. The study had two objectives; the first was to assess the level of discordance in our setting, and the second was to explore if the admitting teams recognize which of their patients are at risk of discordance and if the discordance can then be resolved during the index admission.

Methods

The study protocol was prospectively approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (HSREB) at Western University (#107845). For those patients where written consent could not be obtained in a timely manner (n = 21), an amendment was filed and approved with the HSREB to include their data retrospectively.

Setting

This quality improvement study was conducted on internal medicine (IM) inpatients at a Canadian academic health sciences centre in a midsized urban community (catchment population 1 million). Patients are admitted to one of the three IM teams that typically manage 80–90 patients at any given instance averaging 3,800 admissions per year. Admitted patients usually have multimorbidity15 and high readmission rates.16 As per hospital policy, healthcare teams are expected to elicit and document resuscitation preferences for all their patients at admission.

Recruitment

Patients were included if they were ≥ 55 yr with one or more chronic active problems, such as chronic lung disease, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, kidney disease, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, cancer, or dementia. Exclusion criteria for both groups were an inability to communicate in English, a hearing impairment, an anticipated death or discharge within 24 hr, or a referral to palliative care during the index admission.

Study design

Two ICU RNs with more than 40 years of collective clinical experience were incorporated into IM teams (each two days/week) from 1 August 2016 to 31 August 2018 with the dedicated task of helping the teams elicit resuscitation preferences and goals of care. To get the teams and the nurses working together, context was provided to healthcare teams through email communication, presentations on rounds, formal meetings with IM teams, and educational sessions for allied healthcare staff. Training was provided prospectively through discussion of typical cases over a series of team meetings, role play and an extensive review of literature that included a number of recent advance care planning conversation guides.17,18,19,20,21,22 The trained nurses used an open-ended conversation format for eliciting values and beliefs23,24 to ensure provision of patient-centred care while explaining the different resuscitation options (Table 1)25 and their relationship to patient values.

The multifaceted intervention involved: 1) ascertaining and clarifying resuscitation preferences and fostering shared-decision making (SDM); 2) documentation of the discussions in a designated place in the electronic medical record; and 3) sharing findings with the medical team. The study had two groups; group I consisted of patients specifically referred to the trained nurses by healthcare teams who were invited to ‘identify which of their patients might benefit from further conversations about resuscitation preferences’. Initially, these referrals were done in person as the RNs participated in morning rounds with the team. Once the RNs had spent time with each team so that they were familiar with each other and the project, many of the consults occurred by paging the RN. Group II patients were randomly selected by the study team based on a random number generator (https://www.random.org/) from 1 to 26. This number was correlated with alphabet letters and the first patient on the daily work list with the matching corresponding first letter of their last name was approached for the intervention. If this patient had already been assessed by the trained nurses via referral or randomization, another random patient from the worklist was selected. Post-intervention support was provided via debriefs by the RNs or allied healthcare team members including social workers as per standard of care.

Discordance was defined as a difference between the documented resuscitation preferences (Table 1)25 and those ascertained by the trained nurses. Institutional policy allows only physicians to enter resuscitation orders, hence when discordance was discovered, a physician from the healthcare team was prompted to communicate with the patient/SDM again, confirm patient’s expressed preferences, and change resuscitation orders as appropriate. In the remainder of this document, those instances where patients preferred more intensive resuscitation than was initially documented will be referred to as “escalation” and vice-versa as “de-escalation”.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics (Table 2) were described using means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables (depending on their distributions) and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Student t test or Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables for comparison of outcomes. To obtain exploratory, hypothesis-generating inferences about factors which were potentially predictive of discordance, we used a multivariable logistic regression model that included a priori clinically relevant covariates known5,13 or assumed to be associated with discordance (Table 5). Goodness of fit and discrimination of the logistic regression model were tested using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and the C-statistic respectively. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

We had initially aimed to recruit 400–600 patients; this would, given an anticipated discordance rate of 23% observed and an incomplete resuscitation order rate of 10% in the earlier phase of this study (unpublished data), result in approximately 100 discordances (the dependent variable). This would allow for an a priori evaluation of eight to ten clinically relevant covariates (independent variables) potentially associated with discordance. The study was terminated 1) once we had accumulated 110 discordances; or 2) when the hospital created a new position to continue this work on the unit.

Results

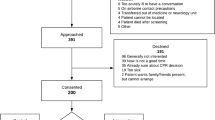

A total of 393 patients were approached for participation and the intervention was provided to all patients or their SDMs. Thirty-seven (10%) patients with out-dated default attempt resuscitation status were excluded; 21 patients refused to have their data included in any research analysis and a complete conversation could not be held with six patients, leaving 329 patients for analysis. At the time of intervention, resuscitation preferences had been elicited and documented by the healthcare teams for 325 (98.5%) of these patients as per standard of care.

The trained nurses were well received by the hospital administration. Sixty-four (19%) patients evaluated did not have capacity (as determined by IM physicians), necessitating further conversations with SDMs as per standard of care. Two hundred and sixty-three (80%) patients required one meeting (Table 3); 69 patients (20%) patients required another conversation lasting a median [interquartile range (IQR)] of 22 [15–32] min. Patients in both groups were similar with regards to initial resuscitation orders and resources needed for elicitation of resuscitation preferences by the trained nurses. Nevertheless, referred patients (group I) had a higher discordance (38% [63/165]) than randomly selected patients (group II) did (16% [27/164]; P < 0.001). Ninety-three percent (84/90) of patients with discordance expressed preferences for de-escalation of care (Tables 3, 4).

Identified discordances are characterized in Table 4. Of the 194 patients with an initial attempt resuscitation order, 42 (21%) preferred a care plan that did not involve CPR. Seventy percent (30/42) of these expressed preferences were for care that would not involve an ICU admission (Tables 3, 4). Of the 36 patients initially designated do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) advanced (i.e., admission to ICU if needed), 15 (41%) declined ICU care. Moreover, the proportion of patients who were originally designated DNAR restricted (i.e., did not want to go to ICU nor receive non-invasive ventilation) increased from 39/329 (11%) to 77/329 (23%) after the intervention. Healthcare teams applied the recommendations of the trained research nurses in 63/69 (91%) de-escalations—the difference for six patients being only the degree of de-escalation. Of the six patients who wanted escalation of their care plans, four wanted a limited period of resuscitation for reversible issues that could not be adequately captured on the resuscitation form and the intervention facilitated detailed documentation of preferences.

In a hypothesis-generating analysis, multivariable logistic regression showed that discordance was independently associated with increasing age (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.05; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02 to 1.08 per additional year of age; P < 0.001), and team referral vs random selection (aOR], 3.92; 95% CI, 2.50 to 8.71; P < 0.001) (Table 5).

Discussion

Getting resuscitation preferences right is essential. Once a patient has been admitted to the ICU, it is often only the SDMs that can communicate the preferences of their loved ones to the healthcare team. This is particularly problematic because recent literature has suggested poor levels of communication between individuals and their SDMs.26 Most participants believe that their SDMs would know their wishes, but are unable to describe any explicit conversations with them and simultaneously admit that they have not discussed any of these preferences with them.26 Given that almost 30% of patients require ICU care in the last 30 days of life,27 failure to document resuscitation status correctly can come at a great cost to the patient, the family, the provider, and the healthcare system.

This study highlights that the incidence of discordance between patients’ expressed resuscitation preferences following a meaningful in-depth conversation of resuscitation options, and those documented in their medical records was quite high (16%) with the majority (93%) of patients indicating less invasive resuscitation preferences. Twenty-one percent of patients documented as preferring full resuscitation on their healthcare records expressed preferences for not receiving CPR. Forty-two percent of those documented for ICU care expressed preferences against it. While healthcare teams could recognize many patients who would benefit from more in-depth exploration of preferences, other randomly selected patients also showed discordance. Regardless, trained nurses could help elicit and reconcile resuscitation preferences in real-time.

Contributors to discordance are poorly described. Eliciting goals of care and resuscitation preferences is challenging in acute care settings, and trainees who are commonly entrusted to complete this task lack the education and experience.28,29 Decision-making is also fraught with preference instability30 as well as conflicts between values and treatment preferences.31 Similar to our results, increasing age has been reported as an independent risk factor for discordance.5,7 In contrast to other studies, however, factors such as frailty and a lack of SDM5,7,13 were not associated with discordance in this study. Nevertheless, this study adds to the literature in a key way. Referrals from the healthcare teams were the strongest independent predictor of discordance (aOR, 3.92). We believe that the healthcare teams likely had valuable clinical context about their patients and, hence, their referrals might lead to inclusion of patients with higher discordance (Table 3). Less clear were the case features that would have triggered this recognition. Was it simply patients whom the team disagreed with their initially expressed choices or were there other features raising their concerns? Answering this question is important so that the teams can better target conversations to those who need them most. With increasing complexity of patients being admitted to Canadian hospitals32 and their high risk of requiring ICU care with life-sustaining interventions,33 reducing discordance should be a high priority for improving health services. Given that discordance was still noted in randomly selected patients (group II) in our setting, it would be premature at this stage to restrict conversations to those solely identified by the team.

Although recognized as important, in-depth resuscitation conversations are often suboptimal in clinical settings.34 Time constraints may be a barrier.35,36 Our data supports this notion since > 10% of patients in this study still remained in the ‘default attempt resuscitation’ category (valid only for 24 hr at our institution; Table 1)25 for a median of three days after admission. While improving the ability of physicians and medical trainees to have these conversations is important, in today’s busy practice, it may not be feasible for them to independently hold in-depth conversations with all patients requiring them. This study shows that dedicated nurses with appropriate training can effectively elicit and facilitate reconciliation of resuscitation preferences. While we have not formally presented data on acceptance, the nurses were welcomed onto the teams; their recommendations led to changes in resuscitation orders in the majority of cases, and the hospital created a new nursing position to continue this work. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT)37 attempted similar interventions with less apparent success. Nevertheless, since SUPPORT, noticeable changes have occurred as most hospitals now mandate documentation of resuscitation preferences for nearly all admitted patients. Furthermore, research nurses in SUPPORT were not integrated into the healthcare teams and their communication objectives were different.38

Further research is needed. First, the contextual situatedness of the work requires that it be assessed in other settings. Regulatory guidelines that recommend how and when resuscitation preferences should be elicited and reconciled in the acute care setting will provide a useful benchmark, as will clarification of terminology and legal framework in the Canadian context. While the intervention itself is likely reproducible, the authors strongly believe that those having the conversation should be able to communicate well with healthcare teams as well as with patients. Second, cost-effectiveness analyses are required to quantify the impact of reconciling this discordance. Finally, future studies might want to explore how else to identify patients at risk of discordance so that scarce resources can be targeted towards those most needing them.

This study has limitations. First, we were unable to determine if the discordance was purely based on the quality or timing of initial discussion versus those that may have arisen through emerging information about diagnosis and prognosis. Physician bias has traditionally supported choices to limit treatment options towards end-of-life (EOL) per se rather than fulfillment of individual patient preferences.39 This could have been interpreted as discordance. Furthermore, preference instability27 or response shifts40 (changing internal standards, values, conceptualization of quality of life and preferences for EOL over time) following admission might have reflected decision conflicts26 or increasing adaptability to changing health status,41,42 but identified as discordance. Second, there were a small number of patients where discordance was not resolved in favour of the preference identified by the nurses. Study data (not shown) suggests that most of these patients were discharged soon after the recommended change and we wonder if teams were simply too busy to address a low likely event on a soon to be discharged patient. Third, budgetary limitations made it necessary to limit the study sample to English-speaking individuals. This study was not discriminatory in that it was an innovation to explore and improve on current practice. Since this innovation has now become part of normal practice, if an interpreter is needed, the nurse in the current role will obtain the interpreter. We recognized this retrospectively, and would handle this differently in future studies. It is important to note though that being excluded from the study did not mean that patients did not receive more in-depth conversations; only that those conversations were handled by the healthcare teams as per the standard of care. It is recognized that the demographics of the trained nurses as well as participants may have influenced decision-making. Lastly, our ‘random’ sample was not truly random because surnames were unequally distributed, and the regression model, which identified putative risk factors for discordance, was undoubtedly affected by residual confounding and should be interpreted with caution. Its purpose was for generating hypotheses about potentially important factors predicting discordance; it was not intended, nor does it serve, as a definitive analysis.

Conclusions

Revisiting resuscitation preferences and having effective conversations in the acute care setting can yield a discordance between patients’ expressed resuscitation preferences and those documented in the medical records at admission. Internal medicine teams may not be able to identify all their inpatients at risk of discordance. Once identified, trained nurses can help elicit values and beliefs and reconcile the discordance in real-time. Further research is necessary to evaluate this intervention in the broader clinical setting.

References

Burns JP, Truog RD. The DNR order after 40 years. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 504-6.

Walker E, McMahan R, Barnes D, Katen M, Lamas D, Sudore R. Advance care planning documentation practices and accessibility in the electronic health record: implications for patient safety. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 55: 256-64.

Thurston A, Wayne DB, Feinglass J, Sharma RK. Documentation quality of inpatient code status discussions. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 48: 632-8.

Young KA, Wordingham SE, Strand JJ, Roger VL, Dunlay SM. Discordance of patient-reported and clinician-ordered resuscitation status in patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 53: 745-50.

Heyland DK, Ilan R, Jiang X, You JJ, Dodek P. The prevalence of medical error related to end-of-life communication in Canadian hospitals: results of a multicentre observational study. BMJ Qual Saf 2015; 25: 671-9.

Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, et al. Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 778-87.

Parr JD, Zhang B, Nilsson ME, et al. The influence of age on the likelihood of receiving end-of-life care consistent with patient treatment preferences. J Palliat Med 2010; 13: 719-26.

Cosgriff JA, Pisani M, Bradley EH, O’Leary JR, Fried TR. The association between treatment preferences and trajectories of care at the end-of-life. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22: 1566-71.

Teno JM, Fisher ES, Hamel MB, Coppola K, Dawson NV. Medical care inconsistent with patients ’ treatment goals : association with 1-year Medicare resource use and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 496-500.

Somogyi-Zalud E, Zhong Z, Hamel MB, Lynn J. The use of life-sustaining treatments in hospitalized persons aged 80 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 930-4.

Pasman HR, Kaspers PJ, Deeg DJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Preferences and actual treatment of older adults at the end of life. A mortality follow-back study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61: 1722-9.

Brunner-La Rocca HP, Rickenbacher P, Muzzarelli S, et al. End-of-life preferences of elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 752-9.

Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170: 1533-40.

Turley M, Wang S, Meng D, Kanter MH, Garrido T. An information model for automated assessment of concordance between advance care preferences and care delivered near the end of life. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016; 23: e118-24.

Flegel K. What we need to learn about multimorbidity. CMAJ 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.181046.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Medical Patients Readmitted to Hospital details for London Health Sciences Centre. Available from URL: https://yourhealthsystem.cihi.ca/hsp/indepth?lang=en#/indicator/027/4/O5142/ (accessed September 2020).

You JJ, Dodek P, Lamontagne F, et al. What really matters in end-of-life discussions? Perspectives of patients in hospital with serious illness and their families. CMAJ 2014; 186: E679-87.

You JJ, Fowler RA, Heyland DK. Just ask: discussing goals of care with patients in hospital with serious illness. CMAJ 2014; 186: 425-32.

Bernacki RE, Block SD; American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174: 1994-2003.

Speak Up Ontario. Available from URL: https://www.speakupontario.ca/ (accessed October 2020).

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The Conversation Project. Available from URL: https://theconversationproject.org/about/ (accessed October 2020).

Etchells E, Darzins P, Silberfeld M, et al. Assessment of patient capacity to consent to treatment. J Gen Intern Med 1999; 14: 27-34.

Scheunemann LP, Arnold RM, White DB. The facilitated values history: helping surrogates make authentic decisions for incapacitated patients with advanced illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186: 480-6.

Fahner JC, Beunders AJ, van der Heide A, et al. Interventions guiding advance care planning conversations: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019; 20: 227-48.

London Health Sciences Centre. Resuscitation Status. Available from URL: https://forms.lhsc.on.ca/forms_view/view_file.php?key=9hkg6483la (accessed October 2020).

Taneja R, Faden LY, Schulz V, et al. Advance care planning in community dwellers: a constructivist grounded theory study of values, preferences and conflicts. Palliat Med 2019; 33: 66-73.

Teno JM, Gozalo P, Trivedi AN, et al. Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions among US Medicare beneficiaries, 2000-2015. JAMA 2018; 320: 264-71.

Schmit JM, Meyer LE, Duff JM, Dai Y, Zou F, Close JL. Perspectives on death and dying: a study of resident comfort with end-of-life care. BMC Med Educ 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0819-6.

Arai K, Saiki T, Imafuku R, Kawakami C, Fujisaki K, Suzuki Y. What do Japanese residents learn from treating dying patients? The implications for training in end-of-life care. BMC Med Educ 2017; 17: 205-9.

Auriemma CL, Nguyen CA, Bronheim R, et al. Stability of end-of-life preferences: a systematic review of the evidence. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174: 1085-92.

Heyland DK, Heyland R, Dodek P, et al. Discordance between patients’ stated values and treatment preferences for end-of-life care: results of a multicentre survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017; 7: 292-9.

Roberts KC, Rao DP, Bennett TL, Loukine L, Jayaraman GC. Prevalence and patterns of chronic disease multimorbidity and associated determinants in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2015; 35: 87-94.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Care in Canadian ICUs; August 2016. Available from URL: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/ICU_Report_EN.pdf (accesed October 2020).

Hall CC, Lugton J, Spiller JA, Carduff E. CPR decision-making conversations in the UK: an integrative review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019; 9: 1-11.

Binder AF, Huang GC, Buss MK. Uninformed consent: do medicine residents lack the proper framework for code status discussions? J Hosp Med 2016; 11: 111-6.

Chittenden EH, Clark ST, Pantilat SZ. Discussing resuscitation preferences with patients: challenges and rewards. J Hosp Med 2006; 1: 231-40.

Anonymous. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA 1995; 274: 1591-8.

Lynn J, De Vries KO, Arkes HR, et al. Ineffectiveness of the SUPPORT intervention: review of explanations. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48: S206-13.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Care at the End of Life. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Field MJ, Cassel CK (Eds). Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 1997: 456.

Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med 1999; 48: 1507-15.

Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med 2010; 153: 256-61.

Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, O’Leary JR. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57: 1547-55.

Author contributions

Ravi Taneja, Robert Sibbald, and Mark Goldszmidt contributed significantly to this manuscript by making substantial contributions to study conception, study design, data acquisition, data analysis, and drafting and critically revising the manuscript. Launa Elliott contributed to study design, data collection, and drafting and revising the manuscript. Elizabeth Burke contributed to study design and data collection, and provided feedback on the draft revision of the manuscript. Kristen A. Bishop contributed significantly to this manuscript by making substantial contributions to the analysis of the data as well as drafting and critically revising the manuscript. Philip M. Jones contributed significantly to this manuscript by making substantial contributions to study conception, study design, data analysis, and drafting and critically revising the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. W. Haddara (critical care), Dr. M. Mrkobrada (internal medicine) and all CTU staff at University Hospital, London Health Sciences Centre for collaborative efforts and helpful discussions as well as Dr. D. Bainbridge (anesthesia) for reviewing the manuscript.

Disclosures

None.

Funding

AMOSO Opportunities Grant (RT) # S15-001. AMOSO Innovations Grant (RT, RS) # INN17-003.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Alana M. Flexman, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Taneja, R., Sibbald, R., Elliott, L. et al. Exploring and reconciling discordance between documented and preferred resuscitation preferences for hospitalized patients: a quality improvement study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 68, 530–540 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01906-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01906-y