Abstract

Purpose of Review

Bone-modifying agents have an important role in the treatment of patients with bone mineral density loss, early-stage breast cancer to reduce risk of recurrence, and metastatic breast cancer with bone involvement. Here we review mechanisms of action of these agents and clinical indications for their use.

Recent Findings

The meta-analysis undertaken by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group showed that the use of bisphosphonates was associated with a decreased risk of breast cancer recurrence.

Summary

The effect of bisphosphonates and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand inhibitors on bone health provides an opportunity to decrease the incidence of skeletal-related events and improve cancer outcomes in certain subsets of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with breast cancer commonly suffer from bone complications. In both localized and advanced disease, accelerated bone mineral density (BMD) loss can occur due to anticancer treatments. Additionally, approximately 70% of patients with metastatic breast cancer will have osseous involvement [1], altering the integrity of their mineralized bone matrix. Strategies to preserve bone health are therefore an important aspect of breast cancer care.

Mechanism of Action of Bone-Modifying Agents

Osteoclast activation is the main mechanism responsible for both accelerated BMD loss and osteolytic metastases associated with breast cancer. When osteoclasts are activated, multiple signaling cascades are turned on that destabilize the mineralized bone matrix, thereby accelerating BMD loss and creating an environment favorable for tumor cell introduction and overgrowth [2, 3]. Bone-modifying agents, including bisphosphonates (e.g., zoledronic acid) and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) inhibitors (e.g., denosumab), modulate osteoclastic activity to suppress these effects. In preclinical models, bisphosphonate use led to a reduction in the release of bone-derived growth factors [4] and an increase in cytotoxic T cells [5, 6], both of which likely inhibit cancer activity within the bone. Previous studies have also identified increased clearance of disseminated tumor cells, including within the bone marrow, in patients with high-risk, early-stage breast cancer treated with monthly zoledronic acid in addition to chemotherapy, compared to chemotherapy alone [7,8,9].

Oral and intravenous (IV) bisphosphonates protect bone integrity and density by interrupting hydroxyapatite crystal dissolution during osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. Additionally, bisphosphonates are internalized by endocytosis into osteoclasts leading to apoptosis, thereby providing further protection against osteoclast-mediated resorption in the setting of increased cell death [10]. With second- and third-generation nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, the enzyme farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) is also inhibited, leading to further dysregulation of osteoclast function by creating osteoclast cytoskeletal abnormalities and promoting osteoclast separation from the bone [10]. Denosumab is a fully humanized IgG2 monoclonal antibody against RANKL, which activates a receptor expressed on osteoblasts which is a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family of proteins. Normally, RANKL activates immature osteoclasts to promote osteoclast differentiation, and inhibition of RANKL therefore suppresses this function. Bisphosphonates and RANKL inhibitors may have additional antitumor effects that create a setting less suitable for micrometastatic disease, such as altering tumor vasculature and the immune microenvironment [11, 12]. Notably, levels of RANKL are increased in the presence of bone metastases [13].

Breast Cancer Treatment Impact on Bone Mineral Density

Several integral therapies used to treat breast cancer are associated with loss of BMD. In premenopausal women treated with chemotherapy, the rate of BMD loss is approximately 3–6% within 12 months of initiating chemotherapy [14,15,16]. While it is unlikely that chemotherapy is directly toxic to bone structure, chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea leads to BMD loss. Furthermore, premenopausal patients treated with ovarian function suppression experience a 7–11% BMD loss, with partial recovery after therapy is discontinued assuming menses resume [17]. Adjuvant treatment with tamoxifen can also accelerate BMD loss in premenopausal women, with one study citing a 4.6% loss of BMD from baseline in women who remain premenopausal after chemotherapy [18].

In postmenopausal patients, rates of BMD loss are more pronounced. Following treatment with chemotherapy, postmenopausal women experience up to a 10% loss in BMD [19]. In hormone receptor–positive disease, aromatase inhibitor (AI) use further accelerates BMD loss, with partial recovery after the completion of treatment [20, 21]. In comparison to tamoxifen use, which has been associated with BMD gains in postmenopausal women [22], AI therapy is associated with a 40% relative increase in fracture rate [23]. Additionally, 5 years of AI therapy led to the development of osteopenia in 17% of patients treated on the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone, or in Combination (ATAC) study who previously had normal bone density, and osteoporosis in 5% of patients who were osteopenic at trial enrollment [24]. With extended use of an AI, the risk of developing osteoporosis increases further, with new onset osteoporosis developing in 11% of patients treated with extended letrozole compared to 6% treated with placebo on the MA.17R trial [25].

Taking these findings into account, prophylactic bone-modifying agents have been investigated as an adjunct to breast cancer therapies. Several early trials confirmed the role of oral bisphosphonates (e.g., risedronate, clodronate, and ibandronate) in preventing BMD loss, both in pre and postmenopausal patients, when taken for 2 years in conjunction with therapies for early breast cancer [26,27,28]. More recently, in the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 79809 trial, upfront administration of IV zoledronic acid (4 mg every 3 months for 2 years) in premenopausal women with early breast cancer treated with adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a significant increase in lumbar spine BMD compared to placebo (1.2% gain versus 6.7% loss) [29]. In postmenopausal patients, the Z-FAST and ZO-FAST trials also assessed upfront zoledronic acid therapy compared to delayed therapy and concluded upfront therapy protected against significant BMD loss [30, 31]. Denosumab has also been shown to reduce BMD loss and aromatase inhibitor-associated fractures in postmenopausal patients [32]. Given these findings, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends initiation of bone-modifying agents for postmenopausal women with a history of a fragility fracture, or with osteoporosis identified on a BMD scan defined as a T-score of < − 2.5 [33]. Treatment can also be considered for high-risk patients with T-scores between − 1.0 and − 2.4, with high-risk classification based on their Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) score. For most patients, bisphosphonates are favored over denosumab because of the favorable cost and availability of long-term safety data. For patients who are unable to tolerate oral or IV bisphosphonates, denosumab is an alternative option. Additionally, supplemental vitamin D (800 international units daily) and calcium (1200 mg daily) in addition to weight-bearing exercises should be recommended for all patients undergoing breast cancer therapies associated with BMD loss.

Adjuvant Bone-Modifying Agent Therapy and Breast Cancer–Related Outcomes

In addition to preventing BMD loss, bone-modifying agent therapy should be considered as a component of the adjuvant treatment plan in postmenopausal patients with early-stage breast cancer. In one of the first, large studies of adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy, 302 patients with early breast cancer were selected based on the presence of disseminated tumor cells (DTC) in the bone marrow and were randomly assigned to receive or not oral clodronate 1600 mg daily for 2 years [34]. The primary endpoints were incidence and number of new bony and visceral metastases and the length of time to their appearance. After a median follow-up of 8.5 years, 20.4% of patients who received clodronate were deceased compared to 40.7% in the control group (p = 0.049) [35]. However, no significant differences in the incidence of metastases or DFS were appreciated. More recently, adjuvant oral clodronate 1600 mg daily was studied in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-34 trial, where 3311 patients were randomized to receive bisphosphonate therapy or placebo for 3 years. After a median follow-up of 90.7 months, subgroup analyses identified an improved recurrence-free interval (hazard ratio [HR] 0.75, p = 0.045), bone metastasis-free interval (HR 0.62, p = 0.027), and non-bone metastasis-free interval (HR 0.63, p = 0.014) in postmenopausal patients with no differences in OS [36]. In the German Adjuvant Intergroup Node-Positive (GAIN) study, 3023 node-positive early breast cancer patients were randomized to receive either ibandronate 50 mg by mouth daily or placebo for 2 years; overall results were negative but a trend toward improved DFS was seen in postmenopausal patients who received ibandronate (HR 0.81, p = 0.039) [37].

While oral bisphosphonates were chosen in the initial trials, IV formulations are more potent and have been included in the majority of contemporary studies. The ZO-FAST trial, for example, assessed immediate versus delayed adjuvant IV zoledronic acid for 5 years in postmenopausal women, defining indications for delayed use as initiation after a fracture or on-study BMD decrease. Immediate use was associated with improved DFS after a median follow-up of 60 months (HR 0.66, p = 0.0375), with fewer local and distant recurrences [31]. In the ABCSG-12 trial, after a median follow-up of 76 months, premenopausal patients with hormone receptor–positive early breast cancer treated with zoledronic acid 4 mg every 6 months for 3 years in addition to ovarian function suppression and endocrine therapy achieved improved OS (HR 0.59, p = 0.027) and DFS (HR 0.73, p = 0.022) [38, 39]. In this study, the benefit was most pronounced in patients older than age 40. In the AZURE trial, the benefit from 5 years of adjuvant zoledronic acid was again only appreciated in an older population, and specifically in women who were postmenopausal for at least 5 years before enrollment, who had improved OS (HR 0.81, 95% CI (0·63–1·04)) compared to those for whom fewer than 5 years had passed since menopause (HR 1.04, 95% CI (0.86–1.25)) [40, 41]. The benefits of adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer were not reproduced in the Z-FAST study, with a similar DFS and OS seen associated with immediate and delayed use of zoledronic acid for 5 years [42]. In the aforementioned trials for which subgroup analyses included an evaluation of outcomes based on hormone receptor status, no significant differences were appreciated.

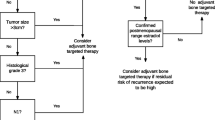

To evaluate the potential magnitude of benefit of adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy in patients with early-stage breast cancer, a large meta-analysis of 18,766 individual patient data was carried out by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) [43••]. Participants were either postmenopausal or premenopausal treated with ovarian function suppression. There was a wide range of the type of bisphosphonate administered and the duration of treatment. The majority of patients included received adjuvant chemotherapy (83%). The study concluded that bisphosphonate therapy was overall associated with a statistically significant improvement in distant recurrence (risk ratio [RR] 0.92, p = 0.03), bone recurrence (RR 0.83, p = 0.004), and breast cancer mortality (RR 0.91, p = 0.04) with a 10-year risk of breast cancer mortality of 16.6% in patients treated with bisphosphonates versus 18.4% in patients who did not receive bisphosphonates. Bisphosphonate therapy was particularly favorable in postmenopausal patients, with an absolute 3.3% reduction in the risk of breast cancer mortality at 10 years and significantly improved bone recurrence rates (RR 0.72, p = 0.002). While the benefit seen was independent of estrogen receptor status, tumor grade, axillary nodal status, and type of adjuvant therapy employed, given that the absolute benefit was small, this approach should be used in patients at higher risk of recurrence. According to the guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and Cancer Care Ontario (CCO), the same criteria used to decide that a patient is a candidate for adjuvant systemic therapy may also apply when deciding on bisphosphonate use [44••].

Also notable from this meta-analysis was that more intense schedules of bisphosphonate therapy, as in the AZURE trial where zoledronic acid was administered every 3–4 weeks for the initial 6 months, were not more efficacious than a more conservative 6-month dosing schedule (more intensive schedule RR 0.84 versus less intensive schedule RR 0.75). Additionally, the specific bisphosphonate used did not significantly affect outcomes, except for pamidronate that was associated with a RR of 1.17 in the 953 patients studied. The ongoing Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) S0307 trial is also assessing outcomes among patients with early breast cancer treated with clodronate, ibandronate, and zoledronic acid. Preliminary evidence suggests a similar 5-year DFS (88%) and OS (93%) benefit regardless of agent [45]. In current clinical practice, IV zoledronic acid is the preferred agent due to patient compliance (once every 6-month IV dosing) coupled with robust clinical data.

In June of 2017, a joint practice guideline from ASCO and CCO was published which recommended adjuvant IV zoledronic acid in appropriate postmenopausal patients, but noted that additional research was needed to clarify the duration, dose, and dosing interval of bone-modifying agent therapy [44••]. At the 2017 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, preliminary results from the SUCCESS trial were reported, showing no benefit for 5 years of extended IV zoledronic acid therapy versus 2 years [46]. Zoledronic acid was given every 3 months for the first 2 years, and every 6 months thereafter for patients randomized to receive 5 years of therapy. The trial included 3754 women with high-risk early breast cancer, and after a median follow-up of 3 years, DFS and OS were similar (90 and 95%, respectively). However, because the number of events was low, the decision to proceed with less than 5 years of adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy should be tailored to the patient’s risk profile.

While the use of RANK ligand inhibitors has not been fully validated in this setting, the results from two trials evaluating adjuvant denosumab and potential anticancer outcomes were recently presented. The Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group (ABCSG)-18 trial enrolled 3425 postmenopausal patients with early-stage breast cancer receiving treatment with AIs. Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive denosumab 60 mg subcutaneously (SQ) every 6 months or placebo during AI therapy for up to 5 years. After a median follow-up of 72 months, the secondary endpoint of disease-free survival (DFS) was significantly improved in the denosumab arm (80.6% at 8 years compared to 77.5% in the placebo group) [47]. Interestingly, the biggest reduction was observed in second primary, non-breast invasive cancers. Although there was no difference in adverse events, we are awaiting long-term follow-up data and overall survival (OS) signals. The D-CARE trial assessed a more intensive adjuvant denosumab regimen (120 mg SQ monthly for six doses then every 3 months for up to 5 years compared to placebo) in high-risk patients regardless of menopausal status, with over 90% of study participants having node-positive disease. The study terminated early in 2018 following a primary analysis that demonstrated the trial did not meet its primary endpoint of bone metastasis-free survival, with no improvements in the postmenopausal cohort either [48]. Investigators also determined 5.4% of patients treated with denosumab developed osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) compared to 0.2% of patients on placebo, and 0.4% of patients on denosumab experienced an atypical femoral fracture. With conflicting outcomes and immature survival data, RANK ligand inhibitor therapy is not endorsed by the national guidelines in the adjuvant setting.

Bone-Modifying Agent Therapy in Metastatic Breast Cancer with Bone Involvement

It is estimated that approximately 20–30% of initial early-stage breast cancers will become metastatic [49, 50] and 6–10% of breast cancers are diagnosed as de novo metastatic disease [51, 52]. Furthermore, 70% of metastatic breast cancer patients have bone involvement, and two thirds of these patients will suffer from a skeletal-related event (SRE) [1]. Skeletal-related events include pathologic fracture, the need for palliative radiation to reduce pain, orthopedic intervention for impending fracture, hypercalcemia, or spinal cord compression.

Patients with metastatic breast cancer and evidence of bone metastases, regardless of menopausal status, should receive a bone-modifying agent to help prevent SREs following the results of multiple randomized clinical trials that confirmed a benefit for this indication (Table 1). According to the ASCO guidelines, bone-modifying agents are recommended for patients with evidence of bone destruction on plain radiographs. In patients with normal plain radiographs and abnormal bone scan, it is reasonable to start bone-modifying agents in the presence of an abnormal CT scan or MRI showing bone destruction. However, this is not recommended for women with only abnormal bone scan but without evidence of bone destruction on radiographs, CT scans, or MRI outside of a clinical trial. Different from bisphosphonate use in the adjuvant setting, there is no survival advantage [55]. Zoledronic acid is favored over pamidronate, due to ease of infusion (15 min every 12 weeks versus 120 min every 4 weeks) and a trend toward decreased long-term risk of SREs [56].

In a recent Cochrane review that summarized nine clinical trials assessing bisphosphonate use versus placebo in patients with osseous metastatic disease (including 2810 breast cancer patients), bisphosphonate therapy reduced the SRE risk by 14% (RR 0.86, p = 0.003) [55]. When evaluating zoledronic acid treatment alone, there was a 41% risk reduction in SREs compared to placebo. No study has compared denosumab to placebo for this indication, though denosumab has been compared to bisphosphonate therapy. In a combined analysis of patients with bone metastases from a variety of solid tumors (36% breast), denosumab 4-week dosing was found to be superior to zoledronic acid 4-week dosing, reducing the risk of first SRE by 17% (HR 0.83, p = <0.001) and delaying the time to first on-study SRE by a median of 8.21 months [57]. This difference was most pronounced in patients with breast and hormone-refractory prostate cancer. In the recent Cochrane Review, three studies of 2345 breast cancer patients demonstrated that denosumab use was associated with a 22% reduction in the risk of developing a SRE compared with bisphosphonates (RR 0.78, p = <0.001) [55]. Two of the included studies assessed 4-week versus 12-week dosing of denosumab, with results favoring 4-week dosing to maintain suppression of bone turnover markers [53, 54]. The phase III clinical trials SAKK 96/12 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02051218) and REaCT-BTA (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02721433) are currently ongoing to further assess the efficacy of a 4-week versus 12-week denosumab schedule.

Regarding zoledronic acid dosing schedules, three randomized controlled trials (ZOOM, OPTIMIZE-2, CALGB 70604) have assessed the efficacy of 12-week versus 4-week dosing in preventing SREs. In each trial, similar rates of SREs were observed regardless of the dosing schedule. In the CALGB 70604 trial, 855 bisphosphonate therapy naïve metastatic breast cancer patients were enrolled and received zoledronic acid for 2 years [58]. Higher rates of ONJ and more frequent elevations in baseline creatinine were appreciated in the 4-week dosing arm (2% versus 1%, p = 0.10; 19.9% versus 15.5%, p = 0.02), whereas rates of SREs were similar (27% with 4-week dosing versus 29%). In the ZOOM and OPTIMIZE-2 trials, approximately 400 patients were enrolled in each trial to receive zoledronic acid every 4 weeks for 1 year, and then were randomized to receive either 4-week or 12-week dosing [59, 60]. Both trials concluded that 12-week dosing was non-inferior (ZOOM SRE rate 26% with 12-week dosing versus 22%; OPTIMIZE-2 SRE rate 23.2% with 12-week dosing versus 22%). Additionally, in a meta-analysis by Ibrahim et al. evaluating five studies that compared a 4-week dosing schedule to 12-week of pamidronate, or zoledronic acid, the 4-week dosing schedule led to a comparable SRE risk (RR 0.90) with higher risks of ONJ (RR 0.83) [61]. Taken together, a 12-week dosing schedule of zoledronic acid is preferred.

If an SRE occurs despite zoledronic acid 4 mg IV every 12 weeks or denosumab 120 mg SQ every 4 weeks, treatment should continue as the patient remains at risk for subsequent SREs. However, one might consider transitioning therapy to a more potent bisphosphonate or from a bisphosphonate to denosumab. Several clinical studies have suggested an improved response with this approach [54, 62, 63].

Regarding the duration of treatment with bone-modifying agents for metastatic breast cancer, the ASCO guidelines recommend indefinite use until evidence of substantial decline in a patient’s general performance status [64••]. However, there is emphasis on the need to weigh the potential benefits and harms of therapy when considering long-term use of these agents.

The OPTIMIZE-2 trial attempted to analyze duration with a discontinuation of zoledronic acid arm after 1 year of therapy; however, accrual was poor. It may be reasonable to consider discontinuation of bone-modifying agents in patients with stable osseous metastatic disease after 3 to 5 years of use, weighing the risks of continued therapy in terms of ONJ and detrimental bone remodeling against likely modest additional benefits.

Considerations Prior to Treatment Initiation

Prior to initiation of a bone-modifying agent for treatment-related BMD loss, adjuvant therapy in postmenopausal patients, or to reduce SREs in patients with osseous metastatic disease, the provider should ensure that the patient has undergone appropriate dental clearance and laboratory evaluations. Additionally, patients should be counseled regarding side effects associated with treatment. Notably, a flu-like prodrome (fever and myalgias) may occur in up to 55% of patients [65], typically within 24 h of the infusion. Subsequent pre-treatment with acetaminophen often ameliorates symptoms. Hypocalcemia may develop, particularly on denosumab therapy, and patients should take supplemental calcium and vitamin D during the duration of treatment with a bone-modifying agent.

Dental Clearance

Bone-modifying agents are associated with a risk of ONJ, which carries significant morbidity. The risk of ONJ increases with frequency, dose, and duration of bisphosphonate therapy, with an incidence of approximately 1.3% [66]. According to Stopeck et al., ONJ was more frequent in patients treated with 2–3 years of denosumab versus zoledronic acid (2.0% versus 1.4%, p = 0.39), and at 5 years, the cumulative incidence of ONJ was 4.7% for denosumab-treated patients versus 3.5% for zoledronic acid [67]. Conversely, Lipton et al. reported similar rates of ONJ in 5677 patients who received denosumab 120 mg versus zoledronic acid 4 mg every 4 weeks, 1.8% versus 1.3%, respectively [57]. Risk factors for developing ONJ include poor oral hygiene, recent history of dental extraction, use of a dental appliance, preexisting periodontal disease, glucocorticosteroid and/or antiangiogenic agent use, or radiation therapy [65, 66]. Therefore, prior to treatment initiation, all patients should undergo a dental examination and complete all invasive dental procedures as indicated (including extractions and implants). Additionally, patients should be directed to maintain good oral hygiene with regular dental preventative visits for the duration of their bone-modifying agent therapy.

Laboratory Evaluations

Bisphosphonate use, mainly with pamidronate, is associated with acute kidney injury, and it is dependent on the dose and the duration of administration (with decreased toxicity associated with lower doses and longer infusion times of IV bisphosphonates). Zoledronic acid dose should be reduced when serum creatinine clearance is ≥ 30 and < 60 mL/min. Because the kidneys do not excrete denosumab, it can be safely used in patients with kidney disease. Hypophosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and hypo or hypermagnesemia may also be appreciated on laboratory evaluations. Hypocalcemia is more common in patients treated with denosumab.

Recommendations

-

1.

Adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy should be considered for patients with early breast cancer that are candidates for systemic therapy, either postmenopausal or premenopausal patients receiving ovarian function suppression

-

Associated with a 3.3% absolute risk reduction in breast cancer mortality.

-

Benefit independent of estrogen receptor status and axillary nodal status.

-

Efficacy of different bisphosphonates appears to be similar, though IV zoledronic acid or oral clodronate are preferred.

-

Limited data for denosumab for this indication.

-

-

2.

Bone-modifying agents (denosumab or bisphosphonates) are recommended for all metastatic breast cancer patients with bone involvement as previously defined

-

Denosumab may be superior to zoledronic acid, though it is associated with increased patient inconvenience (4-week dosing, financial toxicity). Decisions regarding which agent to pursue should take into account patient preference.

-

When zoledronic acid is prescribed for this indication, every 12-week dosing is preferred to every 4-week dosing.

-

If an SRE occurs on bone-modifying agent therapy, the patient should continue to receive treatment but with a different agent.

-

For patients with stable disease, it is reasonable to consider discontinuation of therapy after 5 years, with risks of continued use potentially outweighing further benefit.

-

-

3.

All patients should undergo dental evaluation and laboratory evaluations including a mineral panel and renal function prior to bone-modifying agent treatment initiation.

-

4.

Routine prophylactic bisphosphonate or denosumab use for BMD protection is not recommended for all patients with early-stage, low-risk breast cancer receiving chemotherapy and/or aromatase inhibitors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

Hess KR, Varadhachary GR, Taylor SH, Wei W, Raber MN, Lenzi R, et al. Metastatic patterns in adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106(7):1624–33.

Brown HK, Ottewell PD, Evans CA, Holen I. Location matters: osteoblast and osteoclast distribution is modified by the presence and proximity to breast cancer cells in vivo. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29(8):927–38.

Kaplan RN, Rafii S, Lyden D. Preparing the “soil”: the premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 2006;66(23):11089–93.

Normanno N, Gallo M, Lamura L, De Luca A. Effect of zoledronic acid acts on the interaction between mesenchymal stem cells and breast cancer cells within the bone microenvironment [abstract 10602]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 Suppl):748s.

Morita CT, Jin C, Sarikonda G, Wang H. Nonpeptide antigens, presentation mechanisms, and immunological memory of human Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells: discriminating friend from foe through the recognition of prenyl pyrophosphate antigens. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:59–76.

Clezardin P. Bisphosphonates’ antitumor activity: an unravelled side of a multifaceted drug class. Bone. 2011;48(1):71–9.

Aft R, Naughton M, Trinkaus K, Watson M, Ylagan L, Chavez-MacGregor M, et al. Effect of zoledronic acid on disseminated tumour cells in women with locally advanced breast cancer: an open label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(5):421–8.

Banys M, Solomayer EF, Gebauer G, Janni W, Krawczyk N, Lueck HJ, et al. Influence of zoledronic acid on disseminated tumor cells in bone marrow and survival: results of a prospective clinical trial. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:480.

Rack B, Jückstock J, Genss EM, Schoberth A, Schindlbeck C, Strobl B, et al. Effect of zoledronate on persisting isolated tumour cells in patients with early breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(5):1807–13.

Russell RG, Xia Z, Dunford JE, et al. Bisphosphonates: an update on mechanisms of action and how these relate to clinical efficacy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1117:209–57.

Holen I, Coleman RE. Anti-tumour activity of bisphosphonates in preclinical models of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:214.

Santini D, Stumbo L, Spoto C, D’Onofrio L, Pantano F, Iuliani M, et al. Bisphosphonates as anticancer agents in early breast cancer: preclinical and clinical evidence. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:121.

Kasimir-Bauer S, Bittner AK, Goebel A, et al. Serum levels of RANKL are increased in primary breast cancer patients in the presence of disseminated tumor cells in the bone marrow. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. 2016, Abstract P6–07-11.

Shapiro CL, Manola J, Leboff M. Ovarian failure after adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with rapid bone loss in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(14):3306–11.

Powles TJ, McCloskey E, Paterson AH, et al. Oral clodronate and reduction in loss of bone mineral density in women with operable primary breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(9):704–8.

Saarto T, Blomqvist C, Valimaki M, et al. Chemical castration induced by adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil chemotherapy causes rapid bone loss that is reduced by clodronate: a randomized study in premenopausal breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(4):1341–7.

Gnant M, Mlineritsch B, Luschin-Ebengreuth G, Kainberger F, Kässmann H, Piswanger-Sölkner JC, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy plus zoledronic acid in premenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: 5-year follow up of the ABCSG-12 bone-mineral density substudy. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(9):840–9.

Vehmanen L, Elomaa I, Blomqvist C, Saarto T. Tamoxifen treatment after adjuvant chemotherapy has opposite effects on bone mineral density in premenopausal patients depending on menstrual status. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(4):675–80.

Van Poznak C, Morris PG, D'Andrea G, et al. Bone mineral density (BMD) changes at 1 year in postmenopausal women who are not receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer (BCA). San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. 2009. Abstract 1066.

Eastell R, Adams J, Clack G, Howell A, Cuzick J, Mackey J, et al. Long-term effects of anastrozole on bone mineral density: 7-year results from the ATAC trial. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(4):857–62.

Coleman RE, Banks LM, Girgis SI, Vrdoljak E, Fox J, Cawthorn SJ, et al. Reversal of skeletal effects of endocrine treatments in the intergroup exemestane study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124:153–61.

Love RR, Mazess RB, Barden HS, Epstein S, Newcomb PA, Jordan VC, et al. Effects of tamoxifen on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:852–6.

Mouridsen H, Giobbie-Hurder A, Goldhirsch A, et al. Letrozole therapy alone or in sequence with tamoxifen in women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(8):766–76.

Eastell R, Adams JE, Coleman RE, Howell A, Hannon RA, Cuzick J, et al. Effect of anastrazole on bone mineral density: 5-year results from the anastrazole, tamoxifen, alone or in combination trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(7):1051–7.

Goss PE, Ingle JN, Pritchard KI, Robert NJ, Muss H, Gralow J, et al. Extending aromatase-inhibitor adjuvant therapy to 10 years. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):209–19.

Delmas PD, Balena R, Confravreux E, Hardouin C, Hardy P, Bremond A. Bisphosphonate risedronate prevents bone loss in women with artificial menopause due to chemotherapy of breast cancer: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):955–62.

Saarto T, Blomqvist C, Valimaki M, et al. Chemical castration induced by adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil chemotherapy causes rapid bone loss that is reduced by clodronate: a randomized study in premeno-pausal breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1341–7.

Lester JE, Dodwell D, Purohit OP. Prevention of anastrazole-induced bone loss with monthly oral ibandronate during adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(19):6336–42.

Shapiro CL, Halabi S, Hars V, Archer L, Weckstein D, Kirshner J, et al. Zoledronic acid preserves bone mineral density in premenopausal women who develop ovarian failure due to adjuvant chemotherapy: final results from CALGB 79809. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(5):683–9.

Brufsky A, Harker WG, Beck JT, Carroll R, Tan-Chiu E, Seidler C, et al. Zoledronic acid inhibits adjuvant letrozole-induced bone loss in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:829–36.

Coleman R, de Boer R, Eidtmann H, Llombart A, Davidson N, Neven P, et al. Zoledronic acid (zoledronate) for postmenopausal women with early breast cancer receiving adjuvant letrozole (ZO-FAST study): final 60-month results. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(2):398–405.

Gnant M, Pfeiler G, Dubsky PC, Hubalek M, Greil R, Jakesz R, et al. Adjuvant denosumab in breast cancer (ABCSG-18): a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:433–43.

Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359–81.

Diel IJ, Solomayer EF, Costa SD, Gollan C, Goerner R, Wallwiener D, et al. Reduction in new metastases in breast cancer with adjuvant clodronate treatment. NEJM. 1998;339(6):357–63.

Diel IJ, Jaschke A, Solomayer EF, Gollan C, Bastert G, Sohn C, et al. Adjuvant oral clodronate improves the overall survival of primary breast cancer patients with micrometastases to the bone marrow – a long-term follow up. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(12):2007–11.

Paterson AH, Anderson SJ, Lembersky BC, et al. Oral clodronate for adjuvant treatment of operable breast cancer (National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocol B-34): a multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(7):734–42.

Von Minckwitz G, Mobus V, Schneeweiss A, et al. German adjuvant intergroup node-positive study: a phase III trial to compare oral ibandronate versus observation in patients with high-risk early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(28):3531–9.

Gnant M, Mlineritsch B, Luschin-Ebengreuth G, et al. Long-term follow-up in ABCSG-12: significantly improved overall survival with adjuvant zoledronic acid in premenopausal patients with endocrine-receptor-positive early breast cancer. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. 2011. Abstract S1–02.

Gnant M, Mlineritsch B, Stoeger H, Luschin-Ebengreuth G, Heck D, Menzel C, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy plus zoledronic acid in premenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: 62-month follow-up from the ABCSG-12 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(7):631–41.

Coleman RE, Marshall H, Cameron D, Dodwell D, Burkinshaw R, Keane M, et al. Breast-cancer adjuvant therapy with zoledronic acid. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1396–405.

Coleman R, Cameron D, Dodwell D, Bell R, Wilson C, Rathbone E, et al. Adjuvant zoledronic acid in patients with early breast cancer: final efficacy analysis of the AZURE (BIG 01/04) randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):997–1006.

Brufsky AM, Harker WG, Beck JT, Bosserman L, Vogel C, Seidler C, et al. Final 5-year results of Z-FAST trial: adjuvant zoledronic acid maintains bone mass in postmenopausal breast cancer patients receiving letrozole. Cancer. 2012;118(5):1192–201.

•• Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Adjuvant bisphosphonate treatment in early breast cancer: meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomized trials. Lancet. 2015;386(10001):1353–61. In this meta-analysis bisphosphonates adjuvant use in postmenopausal women was associated with decrease in risk of breast cancer recurrence.

•• Dhesy-Thind S, Fletcher GG, Blanchette PS, et al. Use of adjuvant bisphosphonates and other bone-modifying agents in breast cancer: a cancer care Ontario and American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):2062–81. Most recent CCO/CCF Guidelines on the use of bone modifying agents in the adjuvant setting to decrease risk of breast cancer recurrence.

Gralow J, Barlow WE, Paterson AH, et al. Phase III trial of bisphosphonates as adjuvant therapy in primary breast cancer: SWOG/alliance/ECOG-ACRIN/NCIC clinical trials group/NRG oncology study S0307. American society of clinical oncology annual meeting. 2015. Abstract 503.

Janni W, Friedl TWP, Fehm T, et al. Extended adjuvant bisphosphonate treatment over five years in early breast cancer does not improve disease-free and overall survival compared to two years of treatment. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. 2017. Abstract GS1–06.

Gnant M, Pfeiler G, Steger GG, et al. Adjuvant denosumab in early breast cancer: disease-free survival analysis of 3,425 postmenopausal patients in the ABCSG-18 trial. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2018. Abstract 500.

Coleman RE, Finkelstein D, Barrios CH, et al. Adjuvant denosumab in early breast cancer: first results from the international multicenter randomized phase III placebo controlled D-CARE study. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2018. Abstract 501.

O’Shaughnessy J. Extending survival with chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2015;10(suppl 3):20–9.

Fodor J, Major T, Jozsef T, et al. Comparison of mastectomy with breast-conserving surgery in invasive lobular carcinoma: 15-year results. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2011;16(6):227–31.

Dawood S, Broglio K, Ensor J, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Survival differences among women with de novo stage IV and relapsed breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(11):2169–74.

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. editors. SEER fast stats, 1975-2014. Stage distribution 2005–2014. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/faststats/. Accessed 30 January 2018.

Lipton A, Steger GG, Figueroa J, Alvarado C, Solal-Celigny P, Body JJ, et al. Extended efficacy and safety of denosumab in breast cancer patients with bone metastases not receiving prior bisphosphonate therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(2):6690–6.

Fizazi K, Lipton A, Mariette X, Body JJ, Rahim Y, Gralow JR, et al. Randomized phase II trial of denosumab in patients with bone metastases from prostate cancer, breast cancer, or other neoplasms after intravenous bisphosphonates. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(10):1564–71.

O’Carrigan B, Wong MHF, Willson ML, et al. Bisphosphonates and other bone agents for breast cancer. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017;10.

Rosen LS, Gordon D, Kaminski M, Howell A, Belch A, Mackey J, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid compared with pamidronate disodium in the treatment of skeletal complications in patients with advanced multiple myeloma or breast carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, comparative trial. Cancer. 2003;98(8):1735–44.

Lipton A, Fizazi K, Stopeck AT, Henry DH, Brown JE, Yardley DA, et al. Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: a combined analysis of 3 pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(16):3082–92.

Himelstein AL, Foster JC, Khatcheressian JL, Roberts JD, Seisler DK, Novotny PJ, et al. Effect of longer-interval vs standard dosing of zoledronic acid on skeletal events in patients with bone metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(1):48–58.

Amadori D, Aglietta M, Alessi B, Gianni L, Ibrahim T, Farina G, et al. Efficacy and safety of 12-weekly versus 4-weekly zoledronic acid for prolonged treatment of patients with bone metastases from breast cancer (ZOOM): a phase 3, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):663–70.

Hortobagyi GN, Van Poznak C, Harker WG, et al. Continued treatment effect of zoledronic acid dosing every 12 vs 4 weeks in women with breast cancer metastatic to bone: the OPTIMIZE-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(7):906–12.

Ibrahim MF, Mazzarello S, Shorr R, et al. Should de-escalation of bone-targeting agents be standard of care for patients with bone metastases from breast cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(11):2205–13.

Clemons MJ, Dranitsaris G, Ooi WS, Yogendran G, Sukovic T, Wong BYL, et al. Phase II trial evaluating the palliative benefit of second-line zoledronic acid in breast cancer patients with either a skeletal-related event or progressive bone metastases despite first-line bisphosphonate therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4895–900.

Clemons M, Dranitsaris G, Ooi W, Cole DE. A phase II trial evaluating the palliative benefit of second-line oral ibandronate in breast cancer patients with either a skeletal related event (SRE) or progressive bone metastases (BM) despite standard bisphosphonate (BP) therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108(1):79–85.

•• Van Poznak C, Somerfield MR, Barlow WE, et al. Role of bone-modifying agents in metastatic breast cancer: an American society of clinical oncology-cancer care Ontario focused guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(35):3978–86. Most recent ASCO/CCO guidelines on the use of bone modifying agents in metastatic breast cancer.

Mortimer JE, Pal SK. Safety considerations for use of bone-targeted agents in patients with cancer. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(suppl 1):S66–72.

Saad F, Brown JE, Van Poznak C, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of osteonecrosis of the jaw: integrated analysis from three blinded active-controlled phase III trials in cancer patients with bone metastases. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(5):1341–7.

Stopeck AT, Lipton A, Martin M, et al. Denosumab in patients with breast Cancer and bone metastases previously treated with zoledronic acid or denosumab: results from the 2-year open-label extension treatment phase of a pivotal phase 3 study. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. 2011. Abstract P3–16–07.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Arielle Heeke, Maria Raquel Nunes, and Filipa Lynce declare they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Systemic Therapies

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Heeke, A., Nunes, M.R. & Lynce, F. Bone-Modifying Agents in Early-Stage and Advanced Breast Cancer. Curr Breast Cancer Rep 10, 241–250 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-018-0295-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-018-0295-6