Abstract

Insects from the Dermestidae family (Dermestes ater and Dermestes maculatus) are synanthropic insects, which are household, agricultural and warehouse pests. Their lipidomics and the insects’ ability to use compounds present in their bodies to protect them against pathogens are not fully understood. Therefore, the purpose of this work was to determine the composition of compounds present in the bodies of two insect species, Dermestes ater and Dermestes maculatus, by the MALDI technique. Several free fatty acids and acylglycerols were found to be present as a result of the research. Significant differences in the composition and number of identified compounds have been shown, depending on the tested species and on the development stage. In lipids of D. ater, a greater variety of free fatty acids were found than in those of the second species. Biological studies have determined the high resistance of both species of Dermestidae to fungal infection with Conidiobolus coronatus. These results provide baseline data for further studies on the possible role of lipids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The role of entomopathogenic fungi in regulation of insect pest’s populations is well described (Goettel et al. 2010; Shah and Pell 2003). The way fungi infect insects is made up of several stages including: (1) spore germination on the cuticle of the insect, (2) formation of the invasive structures disrupting cuticle with the help of enzymes (proteases, chitinases, and lipases) degrading the main components of the cuticle such as proteins, chitin and lipids, (3) colonization of the body cavity, and (4) the formation of spores on the insect’s surface allowing fungus to spread in the environment (Gillespie et al. 2000; Ortiz-Urquiza and Keyhani 2013). The defense of insects against the attack of pathogenic fungi takes place with the help of an immune system equipped with hemocytes (insect immunocompetent cells) and numerous antimicrobial peptides, but the main line of defense is the cuticle, which outer layer is covered with lipids (Vilcinskas and Götz 1999; Wojda et al. 2009; Boguś et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2017). Structure and chemical composition of insect cuticle is very heterogeneous and depends on species and developmental stage of insects (Andersen 2012).

Composition of cuticular lipids is considered as the determination factor of insect susceptibility or resistance to entomopathogenic fungi. A number of cuticular lipids show strong antimicrobial properties, however some other can stimulate the germination process, growth and virulence of fungi, thus species specific differences in cuticular lipids profiles may result in differential susceptibility of various insect species to fungal infection (Saito and Aoki 1983; Kerwin 1984; James et al. 2003; Gołębiowski et al. 2008, 2014; Boguś et al. 2010). When looking for new methods to reduce the population of harmful insects with entomopathogenic fungi, it is extremely important to know the lipids profiles of their cuticle. In addition, analysis of the cuticle composition of insects resistant to fungal infection may provide information helpful in searching for effective means of controlling mycoses in humans and farm animals. A soil fungus, Conidiobolus coronatus (Entomophthorales) selectively attacks various insect species (Boguś and Scheller 2002; Boguś et al. 2007) but is also known to cause the rhinofacial mycosis of humans in tropical and subtropical regions (Shaikh et al. 2016).

In the protection of insects against pathogens, the cuticle plays a special role (Wang et al. 2017), as well as the compounds located on it. The insect cuticle may contain compounds with a broad range of molecular weights (from only over 100 g/mol, such as caprylic acid, to large molecules of more than 1000 g/mol, such as triacylglycerols). It is difficult to analyze all these compounds with one analytical method (e.g. GC-MS). The GC-MS technique does not allow for the analysis of all compounds present in the insect cuticle due to the limited size of the analyzed compounds. It is therefore important to use additional analytical techniques, such as high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) combined with a laser light-scattering detector (HPLC-LLSD), spectrophotometer (UV–vis) and diode array detector spectrophotometer (UV–vis DAD), liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS), HPLC with atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization (HPLC/APCI-MS) and matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization (MALDI-MS) (Cerkowniak et al. 2013; Gołębiowski et al. 2011).

MALDI technology offers the non-destructive desorption and ionization of both small and large biomolecules. MALDI-TOF-MS can therefore be used to analyze insect lipids of a relatively high molecular weight. In addition, the MALDI technique offers several advantages over ESI, such as speed of analysis, simplicity and the stability of the ion source. MALDI is also characterized by higher tolerance to salts and other sample impurities (Schiller et al. 2004). Unfortunately, by this method, only sodium and potassium adduct ions are produced. These adduct ions do not produce informative product ion spectra for certain classes of lipids, e.g. TAGs (Duffin et al. 1991; Segall et al. 2005).

The main components of cell membranes are: saturated (SFA), monounsaturated (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) combined with glycerol. They are precursors of eicosanoids (paracrine hormones, prostaglandins), which are the products of the conversion of essential unsaturated fatty acids (EFAs), such as arachidonic acid, linoleic acid or α-linolenic acid (Hart et al. 2006; Żak and Szołtysek-Bołdys 2001). Due to the lack of double bonds, saturated acids are almost chemically inert and resistant to many drastic factors, such as high temperatures or oxidizing conditions. Sterols and their esters account for about 6% of insect lipids. Steroids are very often hormones and regulators in the body. These compounds are widespread and occur in both animals and plants (Saraiva et al. 2011; Dulf et al. 2012). Typically, they contain 27 to 30 carbon atoms in the molecule. Cholesterol is the most commonly found steroid in insect lipids (Sreekantuswamy and Siddalingaiah 1981; Gołębiowski et al. 2013; Cerkowniak et al. 2013; Wojciechowska et al. 2019). Cholesterol is present in all mammalian cells and body fluids. Thanks to Wieland’s (Nobel Prize 1927) and Windaus’ (Nobel Prize 1928) research, we know the exact structure of cholesterol. In 1936, Callow and Young named all the compounds chemically similar to cholesterol as steroids. In addition, stigmasterol, sitosterol and esters of sterols were also found in insect lipids (Lockey 1988).

Diacylglycerols (DAGs) consist of two fatty acid chains covalently bonded to a glycerol molecule through ester linkages. DAGs exist in two possible forms, as 1,2-diacylglycerols and 1,3-diacylglycerols. DAGs can act as surfactants and are commonly used as emulsifiers in processed foods (Phuah et al. 2015).

Another important group of neutral lipids are triacylglycerols (TAGs). TAGs are esters of glycerol and three fatty acids (Nelson and Cox 2000). We distinguish saturated and unsaturated TAGs, which have double bonds between some of the carbon atoms, reducing the number of places where hydrogen atoms can bond to carbon atoms. Triglycerides are components of the body fat of humans, other animals and vegetables. They are also present in the blood and are a major component of human skin oils (Lampe et al. 1983).

The large amount and variety of compounds present on the surface of and inside insects are certainly important for the behavior of the insect, and for its protective ability. Possibly, these compounds interact with each other (Kühbandner et al. 2012). Moreover, the MALDI-MS technique is useful to study the chemical interfaces in plant−pest interactions (Klein et al. 2015).

This paper describes the qualitative and quantitative comparisons of lipid profiles of Dermestes ater DeGeer, 1774 and Dermestes maculatus DeGeer, 1774 larvae and pupae, male and female. These results provide baseline data for further studies on the possible role of lipids. As biological tests have shown, they are pests with a high resistance to entomopathogenic fungi, so the purpose of the work was to identify compounds with potential biological properties. For proper analysis, the MALDI-TOF-MS technique was used to identify compounds of different sizes, which would not have been possible using the GC-MS technique.

Materials and methods

Insects

For the study, Dermestes ater and Dermestes maculatus were used, from different developmental stages of the insect: males, females, pupae, larvae and exuviae. The insects were obtained from the Institute of Parasitology of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. The larvae of D. maculatus and D. ater may molt from five to eleven times. The total duration of the larval period is dependent on the temperature, relative humidity, available moisture in the food, and the type of food (Hinton 1945; Haines and Rees 1989). Both Dermestes species were kept at 25 °C with cyclic changes of light (L:D 12:12), relative humidity at 70%, in separate glass aquaria with a layer of wood shavings spread on the bottom, and covered with mesh cloth to prevent insects from escaping. The beetles and larvae were fed beef meat ad libitum. Four groups of larvae were selected: LVS - very small larvae (size 3–4 mm), LS - small larvae (size 5–6 mm), LM - medium larvae (size 8–9 mm), LB - big larvae (size 12–15 mm). In order to select pupae, the fully grown final instar larvae, which had ceased feeding (size 12–15 mm), were regularly isolated from the basic colonies and kept in glass jars with wood shavings until pupation so as to avoid the slaughtering of larvae immobilized before pupation and naked pupae by younger larvae. For the experiments, one-day-old pupae were used. Adults collected from the basic colonies every 3 days were sexed under a stereo microscope and used either in biological tests or for the extraction of cuticular lipids.

A culture of the wax moth Galleria mellonella was reared, as described earlier (Boguś et al. 2007). Fully grown last instar larvae were collected before pupation and either used for routine testing virulence of Coniodiobolus coronatus colonies or after surface-sterilizationa and homogenization were used as a supplement in the fungal cultures.

Exposition to fungus

Conidiobolus coronatus strain number 3491, isolated from Dendrolaelaps spp., was obtained from the collection of Prof. Bałazy (Polish Academy of Sciences, Research Center for the Agricultural and Forest Environment, Poznań). C. coronatus was routinely cultured on a Sabouraud agar medium (SAM) with the addition of homogenized Galleria mellonella (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae) larvae at a final concentration of 10% wet weight to enhance the sporulation and virulence of the SAM cultures. The cultures were maintained at 20 °C with periodic changes of light (L:D 12:12) to stimulate sporulation (Callaghan 1969).

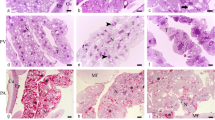

The insects were exposed for 18 h to fully-grown seven-day-old sporulating colonies of C. coronatus (10–20 individuals were placed in a 90 mm Petri dish containing a fungal colony). The control insects were exposed for 18 h to a sterile SAM. The exposure of the tested insects to a C. coronatus colony for 18 h at 20 °C and L:D 12:12 was found to be the most efficient method for resembling the natural infection process (Wieloch and Boguś 2005). In parallel, the virulence of the fungus towards G. mellonella larvae was tested in an analogous manner. G. mellonella is frequently used as a model host for fungal and other microbial pathogens (Binder et al. 2016). After termination of the exposure, insects were transferred to their growing conditions (Dermestidae 25 °C, L:D 12:12; G. mellonella 30 °C, darkness, respectively). The condition of the exposed and control insects of all three species was monitored daily for 10 consecutive days.

Extraction of cuticular lipids

Three-stage solvent extraction was used to extract the compounds present in the insect. Thawed and weighed insects were subjected to solvent extraction (50 ml of organic solvent was used). The extraction was carried out with petroleum ether (60 s - extract I) and dichloromethane (5 min - extract II, 3 months - extract III) (Gołębiowski et al. 2016b).

Ultimately, 45 extracts of lipids from Dermestidae were produced by this extraction method. Because the largest amounts of macromolecular compounds in the lipids of insects (triacylglycerols) were in the third extracts (the longest), these extracts were selected for MALDI analysis. Table 1 lists the number of insects, the names of the samples, their weights and the designations of the samples.

MALDI-TOF-MS conditions

MALDI-TOF-MS mass spectra were recorded in positive ion mode ([M]+, [M + H]+, [M + Na] + and [M + K]+) at 19 and 20 kV. The range of masses in the MALDI-TOF spectrum varied from 190 to 1500 Da. Lipid samples were dissolved before analysis in ethanol and mixed with a saturated solution of the matrix - 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB).

Results

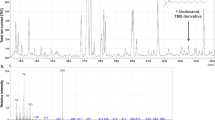

For the study, dichloromethane extracts of two insect species: Dermestes ater and Dermestes maculatus were used, from different developmental stages of the insect: males, females, pupae, larvae and exuviae. The insects were obtained from the Institute of Parasitology of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. 15 samples of insect extracts were used for MALDI analysis. The names of the samples, their weights and the designations of the samples are shown in Table 1. The identification of individual compounds was made using known m/z values. Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 show the percentage content of compounds identified in the individual development stages of D. ater and D. maculatus. As a result of the analysis, a number of free fatty acids, acylglycerols and sterols were identified.

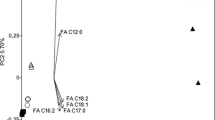

In the case of D. ater, the smallest amounts of compounds were identified in male and female lipids (11 and 12, respectively). There were definitely more compounds in the lipids of larvae (LVS – LB) of D. ater (27 compounds) than from the adult insects and pupae of this species. In the case of D. maculatus, the smallest amounts of compounds were found also in the extracts of males (12 compounds) and females (10 compounds). Most of the compounds were identified in the lipids of the larvae of D. ater (23 compounds) and D. maculatus (20 compounds). A circular diagram with the number of compounds identified by MALDI-TOF-MS analyses in the lipids of D. maculatus and D. ater is presented in Figs. 1 and 2.

Among the acids, the presence of both saturated (C13:0, C16:0, C18:0, C20:0), as well as unsaturated acids (C12:1, C15:1, C16:2, C19:3, C19:4, C20:1, C23:1, C23:2) was found. Tables 2 and 3 contain the composition and content of particular fatty acids. C12:1 acid was found in all extracts of both insect species. C18:0 and C16:0 acids were also often present in the extracts. The presence of such acids as: C19:4, C20:1 and C20:0 was found only in D. ater extracts. The acids: C19:3 and C23:2 are typical for the D. maculatus species. Furthermore, there are significant amounts of diacylglycerols (Tables 4 and 5) and triacylglycerols (Tables 6 and 7) in the lipids of D. ater and D. maculatus. In the composition of diacylglycerols, the following acids: PP (C16:0, C16:0) and OO (C18:1, C18:1) were most often identified. The DAGs: EnEn / BuCa and MLn were only present in the lipids of D. ater. DAGs specific to D. maculatus were ALn / LG. Almost in all extracts of both species of insects, such triacylglycerols as LLS, OOL and LLP were also identified. However, the lipid composition of the two species was quite different. In D. ater, lipids have been found to have a greater variety of free fatty acids than in lipids of the second species. There were more triacylglycerols in the case of D. maculatus: LnLnLa, LaLLn, LnLnS / LLL, LaMLn, MML / PoPoM / OOCa, LLG, OOG were found only in this species. Only in the lipids of D. ater were such TAGs identified as: BuBuCy /VVCo, BuBuS / VVP / CoCoM / CyCyA / EnEnLa / PgPgCy / CaCaCo, LnLnCa, PoPoLn / MLLn, LLPo and LnLnLn. Among the sterols, the presence of cholesterol and campesterol was found in both insect species (Table 8). Biological studies have determined the high resistance of the two Dermestidae species to C. coronatus infection (Table 9). For the larvae and pupae of D. ater and D. maculatus the resistance was more than 86% and 92%, respectively. The adult imago of both Dermestidae species was 100% resistant to C. coronatus infection. They are therefore completely insensitive to infection from this entomopathogenic fungus contrasting with high sensitivity of G. mellonella larvae to the same treatment (mortality: 93.3 ± 2.4%).

Discussion

D. ater and D. maculatus are pests found in food stores, warehouses, etc. The problem of combating these pests makes it necessary to know the lipid composition of the compounds present in these insects. These compounds may be important not only as the insect’s structural component, but also as a chemical barrier to external factors such as insecticides.

In biological extracts, neutral lipids, including diacylglycerols (DAGs), triacylglycerols (TAGs) and sterols are present. These lipids are present in all cells of animals and plants. They play a variety of biochemical functions: they store energy (in fat tissues in organisms) and are precursor pools for signaling molecules (a result of the occupation of membrane receptors) (Murphy et al. 2011), and they also provide defence against harmful factors, e.g. chemicals, microbials and insecticides, which can be used against pest insects (Lockey 1988; Buckner 1993; Laznik et al. 2010; Rojht et al. 2012; Gołębiowski et al. 2014).

MALDI technology is an increasingly popular technique used in lipid and protein analysis (Fuchs et al. 2010; Fuchs and Schiller 2009). This technique is widely used for both fatty acid and acylglycerol analysis. Thanks to MALDI, it is possible to analyze whole extracts without the prior division of the sample into fractions, or purification, which is useful in the analysis of insect lipids. Unfortunately, this technique may involve some problems in the identification of compounds. In the analysis of free fatty acids, it is quite difficult if standard MALDI matrices are used. In this situation, we often have to deal with an overlap of matrix signals. The problem is that free fatty acids are particularly abundant in the low mass range. This gets worse when fatty acids have to be analyzed at low concentrations (Fuchs et al. 2010).

Some problems may also be encountered in the case of cholesterol and its esters. Cholesterol is not detectable as the expected H+ adduct, but only subsequent to water elimination at m/z = 369.3 (Schiller et al. 2000). Using standard MALDI matrices such as DHB, there is a considerable overlap between the cholesterol peak and the matrix background (Fuchs et al. 2010).

However, a standard DHB matrix is useful in the analysis of both DAGs, (Benard et al. 1999) as well as TAGs (Asbury et al. 1999) with positive ion MALDI-TOF mass spectra. Malone and Evans (2004) investigated the formation of diglycerides by the loss of fatty acid moieties. Thanks to the differences in abundance, they found that the loss of the central fatty acid seemed to be less favored. In higher abundance, product ions manifested the loss of higher unsaturated fatty acids, and long-chain fatty acids were shown to be favored. Thanks to measuring the product ion intensities, it is possible to distinguish between isomeric TAGs (Zehethofer and Pinto 2008).

In the lipids extracted from Dermestes maculatus and Dermestes ater, carboxylic acids, sterols, diacylglycerols and triacylglycerols were identified. There were some problems with identifying individual compounds. Signals originating from the matrix hindered identification, as these signals interfered with signals derived from carboxylic acids. They were eliminated by comparing with the matrix spectra and plotting the corresponding signals. This problem can be solved, for example, by using another matrix. In addition, it was difficult to identify unequivocally each compound, particularly triacylglycerols, due to identical m/z values. The ability to analyze the entire extract, the ease of preparation and analysis, and a wide range of results makes the MALDI technique the most readily applicable in the analysis of insect lipids.

Compounds identified in the lipids of D. ater and D. maculatus have also been identified in other insect species. Triacylglycerols are the dominant lipid class of internal lipids in all insects (Stanley-Samuelson and Nelson 1993; Kofroňová et al. 2009). Phospholipids and triacylglycerols were identified e.g. in two chinch bug species: Blissus leucopterus leucopterus and B. iowensis (Insecta: Hemiptera; Lygaeidae). The PL and TG fatty acid profiles from B. l. leucopterus and B. iowensis are very similar. Their profiles are characterized by high proportions of 16:1 fatty acid and very low proportions of C18 and C20 PUFAs. Their profiles are similar only to the patterns known from most species of Diptera and differ from the fatty acid compositions known from all other Heteroptera. The fatty acid profiles of most species in Aphidoidea feature very high proportions of 12:0 and 14:0, and relatively small proportions of 18:2n-6 (Fast 1970; Thompson 1973).

The content of triacylglycerols varies greatly depending on the studied insect species, its occurrence, and even environmental factors such as the season. For example, the prepupae of Eurosta solidaginis have an unusual neutral lipid composition, predominated by acetylated TAGs and FFAs. Marshall et al. observed that field-collected E. solidaginis accumulated large quantities of acTAGs for energy storage over winter (Marshall et al. 2014).

The matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization technique was used, among others, for the analysis of lipids of Drosophila melanogaster (Niehoff et al. 2014; Herren et al. 2014). D. melanogaster is a major model organism for numerous lipid-related diseases. Thanks to MALDI, MS image profiles were obtained of six major lipid classes: phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, and triacylglycerols (Niehoff et al. 2014).

The high content and diversity of DAGs and TAGs in the surface and interior lipids of Dermestidae testify to their important role as a backup, and their building role within the organism of the insect, and their contribution to its cuticle. However, the high amount and variety of fatty acids (especially in surface lipids) can be associated with their protective role and antimicrobial properties.

Many free fatty acids found in Dermestidae lipids play an important role in the body of insects. They have a building and structural function in biological membranes as components of phospholipids and glycolipids. Free fatty acids released from triacylglycerols provide excellent energy. On the other hand, derivatives of twenty-carbon fatty acids act as tissue hormones (Żak and Szołtysek-Bołdys 2001). The presence of C20:0 acid was found in the lipids of D. ater. In extracts of both species of Dermestidae, stearic acid (C18:0) and palmitic acid (C16:0) were present. They are particularly important for the body, because they participate in covalent protein modification (Żak and Szołtysek-Bołdys 2001).

Another very important group of compounds present in insect lipids are sterols. Cholesterol (m/z = 369.4) and campesterol (m/z = 400.4) were extracted from D. ater and D. maculatus. Insects cannot synthesize sterols de novo, so they typically require a dietary source. Cholesterol is the dominant sterol in most insects. Plants contain only small amounts of cholesterol, so plant-feeding insects must generate most of their cholesterol by metabolizing plant sterols. Sterols are essential for an insect’s organism, because they are important components of cellular membranes (Jing et al. 2014), they are precursors for many hormones (Bouvaine et al. 2014) and they play a role in regulating genes involved in developmental processes (Jing et al. 2013). The presence of cholesterol was found in e.g. Musca domestica, Sarcophaga carnaria and Caliphora vicina (Gołębiowski et al. 2013). Campesterol was metabolized in the silkworm to cholesterol (Maruyama et al. 1982). Moreover, many sterols have been identified in plants, e.g. sitosterol, stigmasterol and spinasterol (Behmer et al. 2011; Singh et al. 2016).

The biological tests were very interesting, resulting in the high resistance of the two Dermestidae species to C. coronatus infection. The entomopathogenic fungus C. coronatus causes high mortality of various insect species (Boguś et al. 2012; Gołębiowski et al. 2016a). Therefore, the high resistance of D. ater and D. maculatus to infection with this fungus testifies to their extraordinary ability to protect against entomopathogens. The very diverse lipid content and the presence of compounds with already documented protective activity can have a significant effect on such a high insect resistance. For example, the antimicrobial activity is shown by fatty acids and their mixtures. These compounds strongly influence spore germination and mycelium growth. Fatty acids have been found to be toxic to different fungal species, e.g. Paeciliomyces fumoroseus and Conidiobolus coronatus (Saito and Aoki 1983; James et al. 2003). Also the growth of Beauveria bassiana mycelium is inhibited by short-chain saturated fatty acids extracted from Heliotis zea larvae (Smith and Grula 1982). Other studies confirm that fatty acids inhibit fungal growth to varying degrees depending on chain length and presence of double bonds (Gołębiowski et al. 2014). Among the mixture of fatty acids present on insect cuticle, short-chain fatty acids (C6:0, C11:0, C13:0) show the strongest activity against different species of entomopathogenic fungi, e.g. Metarhizium anisopliae, Paecilomyces fumosoroseus, Paecilomyces lilacinus, Lecanicillium lecanii, Beauveria bassiana (Dv-1/07) and Beauveria bassiana (Tve-N39) (Gołębiowski et al. 2014).

In D. ater and D. maculatus, lipids were extracted and 49 compounds belonging to different lipid groups were pre-identified. There was a great diversity in the number and composition of the identified compounds, depending on the species and the developmental stage of the studied insects. Differences in the composition of the compounds found on the cuticle and interior of the insect can be influenced by many individual and environmental factors. In social insects, their position in a group, and the tasks they perform can even be of importance (Bruschini et al. 2008).

Conclusions

The MALDI-TOF-MS method is successful for the determination of high molecular weight compounds of D. maculatus and D. ater. A total of 43 compounds were identified in D. maculatus and D. ater, including fatty acids, DAGs, TAGs and sterols. Thanks to the application of MALDI, organic compounds in Dermestidae lipids have been identified, which could not be identified by the GC-MS technique. The identified compounds can be involved in the chemical defense of insects. Therefore, more experiments need to be conducted to understand the ecological and physiological function of the identified compounds.

References

Andersen, S. O. (2012). Cuticular sclerotization and tanning. Insect Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, 167–192.

Asbury, G. R., Al-Saad, K., Siems, W. F., Hannan, R. H., & Hill Jr., H. H. (1999). Analysis of triacylglycerols and whole oils by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 10, 983–991.

Behmer, S. T., Grebenok, R. J., & Douglas, A. E. (2011). Plant sterols and host plant suitability for a phloem-feeding insect. Functional Ecology, 25, 484–491.

Benard, S., Arnhold, J., Lehnert, M., Schiller, J., & Arnold, K. (1999). Experiments towards quantification of saturated and polyunsaturated diacylglycerols by matrix assisted laser desorption and ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Chemistry and Physics of Lipids, 100, 115–125.

Binder, U., Maurer, E., & Lass-Florl, C. (2016). Galleria mellonella: An invertebrate model to study pathogenicity in correctly defined fungal species. Fungal Biology, 120, 288–295.

Boguś, M. I., Scheller, K. (2002). Extraction of an insecticidal protein fraction from the pathogenic fungus Conidiobolus coronatus. Acta Parasitologica, 47, 66–72.

Boguś, M. I., Kędra, E., Bania, J., Szczepanik, M., Czygier, M., Jabłoński, P., Pasztaleniec, A., Samborski, J., Mazgajska, J., & Polanowski, A. (2007). Different defense strategies of Dendrolimus pini, Galleria mellonella, and Calliphora vicina against fungal infection. Journal of Insect Physiology, 53, 909–922.

Boguś, M. I., Czygier, M., Gołębiowski, M., Kędra, E., Kucińska, J., Mazgajska, J., Samborski, J., Wieloch, W., & Włóka, E. (2010). Effects of insect cuticular fatty acids on in vitro growth and pathogenicity of the entomopathogenic fungus Conidiobolus coronatus. Experimental Parasitology, 125, 400–408.

Boguś, M. I., Ligęza-Żuber, M., Wieloch, W., Włóka, E. (2012). Mechanism of insect paralysis by parasitic fungus Conidiobolus coronatus and insect defense reactions. Chapter in the book titled "Development directions of insect pathology in Poland" ISBN 978-83-62830-11-4 IBL, pp. 225-248.

Bouvaine, S., Faure, M. L., Grebenok, R. J., Behmer, S. T., & Douglas, A. E. (2014). A dietary test of putative deleterious sterols for the aphid Myzus persicae. PLoS One, 9, e86256.

Bruschini, C., Cervo, R., Protti, I., & Turillazzi, S. (2008). Caste differences in venom volatiles and their effect on alarm behaviour in the paper wasp Polistes dominulus (Christ). Journal of Experimental Biology, 211, 2442–2449.

Buckner, J. S. (1993). Cuticular polar lipids of insects. In D. W. Stanley-Samuelson & D. R. Nelson (Eds.), Insect lipids: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology (pp. 227–270). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press ISBN 0-8032-4231-X.

Callaghan, A. A. (1969). Light and spore discharge in Entomophthorales. Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 53, 87–97.

Cerkowniak, M., Puckowski, A., Stepnowski, P., & Gołębiowski, M. (2013). The use of chromatographic techniques for the separation and the identification of insect lipids. Journal of Chromatography B, 937, 67–78.

Duffin, K. L., Henion, J. D., & Shieh, J. J. (1991). Electrospray and tandem mass spectrometric characterization of acylglycerol mixtures that are dissolved in nonpolar solvents. Analytical Chemistry, 63, 1781–1788.

Dulf, F. V., Andrei, S., Bunea, A., & Socaciu, C. (2012). Fatty acid and phytosterol contents of some Romanian wild and cultivated berry pomaces. Chemical Papers, 66, 925–934.

Fast, P. G. (1970). Insect lipids. Progress in the Chemistry of Fats and Other Lipids, 11, 181–242.

Fuchs, B., & Schiller, J. (2009). Application of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in lipidomics. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology, 111, 83–98.

Fuchs, B., Süß, R., & Schiller, J. (2010). An update of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in lipid research. Progress in Lipid Research, 49, 450–475.

Gillespie, J. P., Bailey, A. M., Cobb, B., & Vilcinskas, A. (2000). Fungi as elicitors of insect immune responses. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology, 44, 49–68.

Goettel, M. S, Eilenberg, J., Glare, T. (2010). Entomopathogenic fungi and their role in regulation of insect populations. In “Insect control: Biological and synthetic agents” Gilbert, L. I., Gill S. S., Eds., Academic Press, pp. 387-437.

Gołębiowski, M., Maliński, E., Boguś, M. I., Kumirska, J., & Stepnowski, P. (2008). The cuticular fatty acids of Calliphora vicina, Dendrolimus pini and Galleria mellonella larvae and their role in resistance to fungal infection. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 38, 619–627.

Gołȩbiowski, M., Boguś, M. I., Paszkiewicz, M., & Stepnowski, P. (2011). Cuticular lipids of insects as potential biofungicides: Methods of lipid composition analysis. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 399, 3177–3191.

Gołębiowski, M., Cerkowniak, M., Boguś, M. I., Włóka, E., Przybysz, E., & Stepnowski, P. (2013). Developmental changes in the composition of sterols and glycerol in the cuticular and internal lipids of three species of fly. Chemistry and Biodiversity, 10, 1521–1530.

Gołębiowski, M., Urbanek, A., Oleszczak, A., Dawgul, M., Kamysz, W., Boguś, M. I., & Stepnowski, P. (2014). The antifungal activity of fatty acids of all stages of Sarcophaga carnaria L. (Diptera: Sarcophagidae). Microbiological Research, 169, 279–286.

Gołębiowski, M., Ostachowska, A., Paszkiewicz, M., Boguś, M. I., Włóka, E., Ligżza-Żuber, M., & Stepnowski, P. (2016a). Fatty acids and amino acids of entomopathogenic fungus Conidiobolus coronatus grown on minimal and rich media. Chemical Papers, 70, 1360–1369.

Gołębiowski, M., Cerkowniak, M., Ostachowska, A., Naczk, A. M., Boguś, M. I., & Stepnowski, P. (2016b). Effect of Conidiobolus coronatus on the cuticular and internal lipid composition of Tettigonia viridissima males. Chemistry and Biodiversity, 13, 982–989.

Haines, C. P., Rees, D. P. (1989). Dermestes spp. A field guide to the types of insects and mites infesting cured fish http://www.faoorg/docrep/003/t0146e/T0146E04htm (28 September 2009).

Hart, H., Craine, L. E., Hart, D. J. (2006). Organic chemistry. Short course. Medical Publishing PZWL, pp. 281-289.

Herren, J. K., Paredes, J. C., Schüpfer, F., Arafah, K., Bulet, P., Lemaitre, B. (2014). Insect endosymbiont proliferation is limited by lipid availability. eLife, 3, e02964 elifesciencesorg.

Hinton, H. E. (1945). A monograph of the beetles associated with stored products Volume I British Museum (Natural History) England, pp. 261-268.

James, R. R., Buckner, J. S., & Freeman, T. P. (2003). Cuticular lipids and silverleaf whitefly stage affect conidial germination of Beauveria bassiana and Paecilomyces fumosoroseus. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 84, 67–74.

Jing, X., Grebenok, R. J., & Behmer, S. T. (2013). Sterol/steroid metabolism and absorption in a generalist and specialist caterpillar: Effects of dietary sterol/steroid structure mixture and ratio. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 43, 580–587.

Jing, X., Grebenok, R. J., & Behmer, S. T. (2014). Balance matters: How the ratio of dietary steroids affects caterpillar development growth and reproduction. Journal of Insect Physiology, 67, 85–96.

Kerwin, J. L. (1984). Fatty acid regulation of the germination of Erynia variabilis conidia on adults and puparia of the lesser housefly, Fannia canicularis. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 30, 158–161.

Klein, A. T., Yagnik, G. B., Hohenstein, J. D., Ji, Z., Zi, J., Reichert, M. D., Macintosh, G. C., Yang, B., Peters, R. J., Vela, J., & Lee, Y. J. (2015). Investigation of the chemical interface in the soybean−aphid and rice−bacteria interactions using MALDI-mass spectrometry imaging. Analytical Chemistry, 87, 5294–5301.

Kofroňová, E., Cvačka, J., Jiroš, P., Sýkora, D., & Valterová, I. (2009). Analysis of insect triacylglycerols using liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-mass spectrometry. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology, 111, 519–525.

Kühbandner, S., Sperling, S., Mori, K., & Ruther, J. (2012). Deciphering the signature of cuticular lipids with contact sex pheromone function in a parasitic wasp. Journal of Experimental Biology, 215, 2471–2478.

Lampe, M. A., Burlingame, A. L., Whitney, J., Williams, M. L., Brown, B. E., Roitman, E., & Elias, M. (1983). Human stratum corneum lipids: Characterization and regional variations. Journal of Lipid Research, 24, 120–130.

Laznik, Ž., Tóth, T., Lakatos, T., Vidrih, M., & Trdan, S. (2010). Control of the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata [Say]) on potato under field conditions: A comparison of the efficacy of foliar application of two strains of Steinernema feltiae (Filipjev) and spraying with thiametoxam. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 117, 129–135.

Lockey, K. (1988). Lipids of the insect cuticle origin composition and function. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, 89, 595–645.

Malone, M., & Evans, J. J. (2004). Determining the relative amounts of positional isomers in complex mixtures of triglycerides using reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Lipids, 39, 273–284.

Marshall, K. E., Thomas, R. H., Roxin, Á., Chen, E. K. Y., Brown, J. C. L., Gillies, E. R., & Sinclair, B. J. (2014). Seasonal accumulation of acetylated triacylglycerols by a freeze-tolerant insect. Journal of Experimental Biology, 217, 1580–1587.

Maruyama, S., Fujimoto, Y., Morisaki, M., & Ikekawa, N. (1982). Mechanism of campesterol demethylation in insect. Tetrahedron Letters, 23, 1701–1704.

Murphy, R. C., Leiker, T. J., & Barkley, R. M. (2011). Glycerolipid and cholesterol ester analyses in biological samples by mass spectrometry. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1811, 776–783.

Nelson, D. L., & Cox, M. M. (2000). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (3rd ed.). New York: Worth Publishing ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

Niehoff, A. C., Kettling, H., Pirkl, A., Chiang, Y. N., Dreisewerd, K., & Yew, J. Y. (2014). Analysis of Drosophila lipids by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometric imaging. Analytical Chemistry, 86, 11086–11092.

Ortiz-Urquiza, A., & Keyhani, N. O. (2013). Action on the surface: Entomopathogenic fungi versus the insect cuticle. Insects, 4, 357–374.

Phuah, E. T., Tang, T. K., Lee, Y. Y., Choong, T. S., Tan, C. P., & Lai, O. M. (2015). Review on the current state of diacylglycerol production using enzymatic approach. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 8, 1169–1183.

Rojht, H., Košir, I. J., & Trdan, S. (2012). Chemical analysis of three herbal extracts and observation of their activity against adults of Acanthoscelides obtectus and Leptinotarsa decemlineata using a video tracking system. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 119, 59–67.

Saito, T., & Aoki, J. (1983). Toxicity of free fatty acids on the larval surfaces of two Lepidopterous insects towards Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill. And Paecilomyces fumoso-roseus (wize) Brown et Smith (Deuteromycetes: Moniliales). Applied Entomology and Zoology, 18, 225–233.

Saraiva, D., Semedo, R., Castilho, M. C., Silva, J. M., & Ramos, F. (2011). Selection of the derivatization reagent—The case of human blood cholesterol, its precursors and phytosterols GC–MS analyses. Journal of Chromatography B, 879, 3806–3811.

Schiller, J., Arnhold, J., Glander, H. J., Arnold, K., & Arnold, K. (2000). Lipid analysis of human spermatozoa and seminal plasma by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy – Effects of freezing and thawing. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids, 106, 145–156.

Schiller, J., Suss, R., Arnhold, J., Fuchs, B., Lessig, J., Muller, M., Petkovic, M., Spalteholz, H., Zschornig, O., & Arnold, K. (2004). Matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry in lipid and phospholipid research. Progress in Lipid Research, 43, 449–488.

Segall, S. D., Artz, W. E., Raslan, D. S., Ferraz, V. P., & Takahashi, J. A. (2005). Analysis of triacylglycerol isomers in malysian cocoa cutter using HPLC-mass spectrometry. Food Research International, 38, 167–174.

Shah, P. A., & Pell, J. K. (2003). Entomopathogenic fungi as biological control agents. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 61, 413–423.

Shaikh, N., Hussain, K. A., Petraitiene, R., Schuetz, A. N., & Walsh, T. J. (2016). Entomophthoramycosis: A neglected tropical mycosis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 22, 688–694.

Singh, V., Soni, L. K., Dobhal, S., Jain, S. K., Parasher, P., & Dobha, M. P. (2016). Phytochemicals and pharmacological properties of urginea species. Chemical Science Review and Letters, 5, 79–95.

Smith, R. J., & Grula, E. A. (1982). Toxic components on the larval surface of the corn earworm (Heliothis zea) and their effects on germination and growth of Beauveria bassiana. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 39, 15–22.

Sreekantuswamy, H. S., & Siddalingaiah, K. S. (1981). Sterols and fatty acids from the neutral lipids of desilked silkworm pupae (Bombyx mori L.). Fette, Seifen, Anstrichmittel, 83, 97–99.

Stanley-Samuelson, D. W., Nelson, D. R. (1993). Insect lipids: Chemistry Biochemistry and Biology. University of Nebraska Press Lincoln NE, pp. 45-97.

Thompson, S. N. (1973). A review and comparative characterization of the fatty acid compositions of seven insect orders. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, 45, 467–482.

Vilcinskas, A., & Götz, P. (1999). Parasitic fungi and their interactions with the insect immune system. Advances in Parasitology, 43, 267–313.

Wang, Y., Carballo, R. G., & Moussian, B. (2017). Double cuticle barrier in two global pests the whitefly Trialeurodes vaporariorum and the bedbug Cimex lectularius. Journal of Experimental Biology, 220, 1396–1399.

Wieloch, W., & Boguś, M. I. (2005). Exploring pathogenicity potential of Conidiobolus coronatus against insect larvae in various infection conditions. Pesticides, 4, 133–137.

Wojciechowska, M., Stepnowski, P., & Gołębiowski, M. (2019). Identification and quantitative analysis of lipids and other organic compounds contained in eggs of Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata). Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 126, 379–384.

Wojda, I., Kowalski, P., & Jakubowicz, T. (2009). Humoral immune response of Galleria mellonella larvae after infection by Beauveria bassiana under optima and heat-shock conditions. Journal of Insect Physiology, 55, 525–531.

Żak, I., & Szołtysek-Bołdys, I. (2001). Fatty acid and eicosanoids. Medical Chemistry Katowice ŚAM, pp., 177–192.

Zehethofer, N., & Pinto, D. M. (2008). Recent developments in tandem mass spectrometry for lipidomic analysis. Analytica Chimica Acta, 627, 62–70.

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the National Center of Science grant: UMO-2012/05/N/NZ4/02210, and by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education grant: 531-8617-D594-19. We would like to thank Dr. M. Alicka and Dr. M. Behrendt (University of Gdańsk - Institute of Physics) for providing the electronic scanning microscope.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cerkowniak, M., Boguś, M.I., Włóka, E. et al. The composition of lipid profiles in different developmental stages of Dermestes ater and Dermestes maculatus and their susceptibility to the entomopathogenic fungus Conidiobolus coronatus. Phytoparasitica 48, 247–260 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12600-020-00789-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12600-020-00789-5