Abstract

This introductory paper to the special section argues that there are now significant signs and opportunities of real transformations of food systems in which to create new synergies between sustainable consumption and production, and which can potentially shift agri-food into more secure and sustainable sets of conditions. With reference to empirical research in Europe, the paper assesses the transformative potential of a series of mobilisations associated with: sustainable city networks, community cooperative and share schemes, and regional agro-ecological, seed, plant and livestock schemes. Not denying the significance of countervailing intensive and industrialised food regimes, the paper introduces a set of conceptual building blocks, which emerge as ways of both assessing and progressing these mobilisations. It is argued that to succeed they need elements of at least four conditions: (i) a significant and lasting reconfiguration of governance and regulatory conditions; (ii) an ability and capacity to both promote sustainable production and food access and diet through the development of new assemblages; (iii) develop new social and physical and distributional infrastructures which can scale out their impacts; and (iv) be embedded in a more reflexive governance context which is both supportive and spatially sensitive to their diverse conditions. The succeeding papers in the special issue will deal with these transformatory factors in comparative and empirical depth. Here we outline how and why such a ‘re-building’ has become so critical at this current juncture.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction: rebuilding sustainable food systems in Europe

The European food system currently stands at an important crossroads. It is, on the one hand, still significantly harnessed and embedded in what can be regarded as somewhat outdated and some would argue dysfunctional governance and regulatory systems, which had their origins during a significant period of economic growth, modernisation and plenty, experienced in the later parts of twentieth century. On the other hand, and as we shall see, an entirely new and alternative paradigm is taking shape (see Marsden and Morley 2014) built upon a more diverse and fragmented set of actors and initiatives, and governance arrangements which are commonly called: ‘Alternative Food Networks (AFNs)’ or, as we develop here, Assemblages.

We need to develop a new conceptual vocabulary for these more sustainable systems as they are both expanding and affecting dominant food regimes in new ways. However, this ‘crossroads’ is fraught with contests regarding food politics, policies and effective regulatory systems. The appreciation of these contests and their outcomes are critical when we consider the need to adjust food systems in ways which begin to deliver higher levels of both food and nutrition security (FNS).

In many ways, and particularly resonant since the onset of the food, fuel, financial and fiscal crisis starting 2007–8, we can characterise the current and foreseeable future of food policy in Europe as one which is losing its means of coherent regulation and legitimacy. This means that current and dominant forms of food governance and economy, which we have long taken for granted, are now progressively losing their social and political consent and acceptance and are beginning to lose their powers to reproduce and to justify themselves.

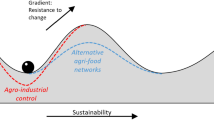

Whilst the burgeoning literature on alternative food networks (AFNs) often too readily asserts and celebrates its heterogeneous and explosive development as a new paradigm, such a movement can only have real transformative potential if, at the same time, we can witness significant evidence of the demise and weakening of current systems of conventional food governance. Indeed, much of transition management theory tells us that overall ‘regime change’ can only occur in food systems when two sets of conditions are beginning to prevail (see Grin et al. 2012; Spaargaren et al. 2012). First, the overriding regulatory regime faces significant and multiple ‘landscape change’ factors which affect its ability to sustain its legitimacy in terms of policy, technology, market regulation and consumer and public confidence. Second, collections and assemblages of niches become vitalised and empowered such that they can pose serious challenges to the dominant regime (Rip and Kemp 1998; Geels and Schot 2007.

It is important, therefore, in analysing the potential transformative potential of ‘alternative food networks’ that we simultaneously consider the evidence of the inherent and contested demise and decline of the current food governance systems. Transformations in food systems (as in broader political economy) thus entail studying both the extant crisis of current systems simultaneously with exploring the anatomies of new FNS systems and assemblages.

In beginning to approach this ‘dual-task’, this introductory paper to this special section of Food Security on FNS starts by mapping out the current nested characteristics of the three major and macro- forms of food governance currently operating in Europe during the more volatile geo-political and economic period that has occurred since 2007–8. We have shown in our recent research, and in many elements of the succeeding set of papers, that we are in the midst of a period of growing vulnerability of food systems, as demonstrated by much of the empirical evidence in the EU funded project (TRANSMANGO).

TRANSMANGO shows that Europe’s food system is, to varying degrees and intensities, stressed and under threat. This involves increasing levels of food poverty, environmental degradation, resource scarcity and climate change. These components are now more fragmented and are working against one another in many ways (see Moragues-Faus et al. 2017). For instance, over a quarter of UK citizens are now experiencing some form of food poverty, and the EU as a whole has lost one out of three farms over the past decade. Food insecurity, obesity, food poverty, increasing food miles and unhealthy food consumption amongst vulnerable groups are gradually and increasingly broadly shared as concerns. Many social actors (e.g. consumer groups, civil society movements, corporate groups, policy makers) are looking for ways to solve the food problem for now as well as in the future. It is widely acknowledged that solving these issues requires transformative change in food systems (Clapp 2016; Lang 2010; Van der Ploeg 2010).

Besides addressing food and nutritional security (FNS) problems, adopting a food systems approach also provides opportunities to address other challenges such as environmental degradation and social injustice (Wiskerke 2015). Challenges to food systems have long been subject to various national and global interventions, programmes and policies. These interventions have traditionally been production and distribution oriented. It is widely recognized in the literature and in policy making and practitioners’ circles that the range of policies and interventions emanating from these interventions have not been able to fully address or solve developing food related problems (Marsden 2013; Wright and Middendorf 2008). We therefore live in a period when the interlinkages or potential synergies among food security, sustainability, sovereignty and their effective governance can no longer be taken for granted.

The past synergies between the regulation of production and mass consumption of relatively ‘cheap’ foods has come to an end, with the reversal of ‘Engel’s Law’, whereby the proportion of household income expended on food and fuel is increasing not decreasing (House of Commons 2013; The Food Foundation 2014). We thus now have a European food crisis which is negatively affecting both ends of the food chain - both those that produce the food- not least through the endemic ‘cost-price’ squeeze - and those who consume it (significant rises in food-related nutritional and related health problems). The highly concentrated corporate food processing, retailing and catering sector continues to abstract the highest proportion of economic value from both their increasingly ‘dedicated’ suppliers (farmers and processors) and their growing segments of impoverished and under-nourished consumers. Since 2007–8 Europe thus faces something of an unprecedented rise in nutritional food insecurity with its interconnected ecological, social and political dimensions.

What has become significant since 2007–8 is that the well-known environmental negative externalities associated with industrialised food - resource depletion and contaminating pathogens, disease and pests - have been joined by a set of human metabolic effects associated with disease; obesity, under-nourishment and decline in healthy life opportunities and expectancy.Footnote 1 We wish to argue here that a major driver for this rise in food insecurity lies primarily in a crisis of food governance, as existing and longstanding governance regimes are no longer capable of delivering effective and long term food security and sustainability.

2 The anatomy of food insecurity: three interconnected (but increasingly fragmenting) regulatory models: food, agriculture and national welfare policies

It can be argued that, for much of the period between the 1980s and 2007–8, Europe enjoyed the benefits of a post-cold war and strong policy synergy between a corporate led, private-interest governance regime on the one hand, and a corporatist EU state-based regulatory regime on the other (see also Marsden et al. 2010). The former allowed, through the adoption of neo-liberal principles, corporate retailers, caterers and food manufacturers to control and police the food system through developing their own private systems of quality control (such as GlobalGap), hygiene management (HACCP), and the development of logistical systems which allowed the cheap transport of goods across long distances at relatively cheap cost (‘just-in-time’). This empowered and positioned the corporate food sector (both retail and caterers) as the archetypal private deliverers of relatively stable food prices and ‘quality’ on behalf of the state.

From the 1980s to 2007, successive governments and the EU encouraged the private sector to manage and deliver public food goods. They could deliver an increasingly vast array of food for their citizens and, at the same time, manage (not least through the externalisation of significant environmental costs) relatively low levels of food inflation. This was very attractive for neo-liberalising governments in the EU. In return, and with the rapid expansion of globalised supply chains, European consumers then experienced a massive growth in consumer food choices at relatively low cost. This also ‘flattened’ the significance of natural seasonality and food geographies, and created massive expansions in standardised but differential ‘just-in-time’ delivery systems (Spaargaren et al. 2012; Busch 2007).

At the same time, the development and maintenance of a Europeanised and still ‘common’ agricultural policy - originally developed to protect producers, while also stabilising prices for consumers - continued to provide and underwrite public financial support for farmers in order for them to be able to pass on lower priced farm-gate goods to the corporate sector, as well as create a baseline regulatory system to support food consumers (through the development of the European Food Safety Agency, for instance).

In addition, and often ignored in these accounts, but indeed to be shown as particularly critical from our TRANSMANGO national reporting, was also the significant role of national social welfare programmes for low income groups, which for a long time enabled food (and fuel) poverty for the lower income groups to be kept at bay. The onset of national and EU ‘austerity’ programmes, which acted to cut state welfare benefits severely, increased food security vulnerabilities, particularly from 2010 onwards.

Together with the vast expansion of relatively cheap imports (not least in fresh fruit and vegetables and fish) from around the world, driven by the corporate retail global sourcing strategies, these tripartite and overriding governance frameworks (i.e food, agriculture and overall state welfare support systems) created a stability in food security from the 1980s until 2007–8.

The onset of the food price crisis in 2007–8 significantly disrupted these synergies among these governance frameworks but did not stop their operation, or their attempts, as we shall see, to re-define the growing problem of food insecurities. Faced with increasing fuel and food costs, greater international instability in geo-politics and food supply (such as the Arab spring and Russian food embargo), the renewed fiscal crisis of both European and national member states, and the emergence of state ‘austerity’ agendas in social welfare programmes, the historical synergies among the established regulatory systems started to weaken. We can see this as part of the beginnings of the end of ‘cheap food’ (see Moore 2015), and indeed as a segment of wider governance crises in industrialised food regimes.

The rise of new civil regulatory assemblages - those around alternative food networks (AFNs), food welfare initiatives, sustainable food cooperatives and buying groups and so on - has emerged very much, as we shall depict in this special section of Food Security, to fill the gaps left by the partial collapse and growing dysfunction experienced by the dominant triumvirate of regulatory systems. This has been fuelled, as much of our empirical evidence has shown, by a much more variegated set of actors involving civil society, small independent businesses, some farmers and landowners, and is based upon more cooperative and collaborative models of governance (see for instance cases such as the UK Sustainable Food Cities network, CSAs in Flanders, Coops schemes in Wales and peri-urban consumer-producer alliances in Spain).

Some consistent features of these alternative regulatory assemblages (McFarlane 2009) are that they are place-based, and sometimes trans-local in character; they are based on developing ‘shorter supply chains’ between producers and consumers; are non-corporate in organisation, and define themselves by being outside the three dominant food regulatory regimes outlined above. Moreover, they explicitly address and aim to solve local and regional forms of food insecurity and sovereignty, as well as often having strong ecologically sustainability goals and visions. Much of the recent agri-food studies literature has now become dominated by exploring and indeed celebrating the explosion of alternative food assemblages (see Goodman et al. 2012; Constance et al. 2015) on both sides of the Atlantic.

We can see that, in the current period, the rise of new and alternative assemblages are being given significantly more energy and vibrancy as the older regulatory regimes progressively lose their legitimacy. Nevertheless, the degree to which these assemblages become potentially transformatory will partly depend upon the continued adjustments and actions of the dominant regulatory structures and the degree to which alternative assemblages can become more embedded and institutionalised without losing their inherent integrity and autonomy.

It is important, however, to recognise that the rise and proliferation of alternative food assemblages in Europe is occurring in a changing policy context with regard to the three major established governance systems outlined above. For instance, the private interest model, during the period of crisis, has attempted to continue to drive down their marginal costs in their supply chains in order to continue to provide relatively cheap food available in its stores (especially by discounting strategies). This has further pressured the producer and small processor sectors, which have had to absorb these pressures (for instance, in the now more deregulated dairy sectors). In addition, many corporate food retailers and manufacturers have attempted to embrace the sustainability and food security agenda by creating ‘green’ sustainability initiatives with their ‘dedicated suppliers’. Pepsico, Nestlé and Tesco, as examples, all now have ‘partnership’ schemes with their suppliers which monitor reductions such as in carbon emissions and water usage. Other European retailers (see the Belgian example elaborated in the collaborative paper by Pedro Cerrada-Serra et al. [this issue]) are transforming their supply chains to circular economy principles in both their procurement and waste reduction processes.

As the food crisis has deepened therefore, we see the private-interest governance model - one which is also becoming more highly financialised - attempting to regain public and consumer legitimacy through corporate greening strategies. The paper by Francesca Galli et al. [this issue] highlights the varying roles of corporate business in addressing European food poverty issues. Greening is now only one challenge for the private interest model. The rising health agenda associated with obesity, diabetes and undernourishment means that the corporate are having to continue to lobby governments to maintain their traditional relations with them and their level of control and flexibility over food safety and quality. They are finding it necessary to continue to articulate their role as the real and trustworthy custodians of the consumer.

The EU state regulatory system is also, in combination with these changes, struggling to maintain its legitimacy. One fairly immediate reaction to the emergence of the food crisis was to regain a justification for productionism, or as it was framed ‘sustainable intensification’. Armed and aligned with several influential scientific bodies, the renewed emphasis and policy direction for ‘solving’ the food security problems was again focussed on neo-productivist approaches. This has been aligned to various R&D, EU and national funding schemes and agro-industrial strategies. In the UK, for instance, a new agri-industrial strategy was announced in 2013 linked to new private/public partnership funding programmes. The emphasis is on sustainable intensification and increases in ‘productivity’ through the application of a new round of digital, big data, and precision farming practices. The assumptions here were (see Beddington et al. 2012) that the growing instabilities and potential FNS problems emerging since 2007–8 could be largely resolved (as indeed in the past) by a recourse to particular technological innovations which could continue to raise food productivity at the same time as progressing environmental sustainability (see Pretty 2013; Horlings and Marsden 2012). Such a productivist answer to the wider FNS problem, as we shall witness below, tended to exclude consideration of both the complexity of downstream food supply linkages, and the increasingly active (and oppositional) role of both consumers and citizens in developing alternative assemblage innovations in meeting changing market demands.

It is important in considering the ‘transformative potential’ of alternative assemblages (see below) to recognise how the dominant governance systems have attempted to reposition themselves given the objective of ‘cheap food’. In one sense, the key governance models - corporate private interest, EU state policy, and new alternative food assemblages - espouse advances in sustainability and FNS; and this places pressures upon the alternative movements, particularly in maintaining their integrity, and in resisting co-option and appropriation of their activities inside, as opposed to outside these dominant regulatory systems. These boundary problems between the interlocking but significantly contested governance systems are a major issue with regard to assessing the transformatory potential of the alternative assemblages. For, as we will see below, one challenge for the new assemblages is to engage with and be part of the deliberations in established governance systems if they are to become more empowered and embedded.

3 Towards a new food security regulatory landscape: opportunities for transformational potential and empowerment

It is now possible to posit several important research questions with regard to both the decline in the legitimacy of established food governance systems, and the rise of new assemblages. How will these relations evolve? Will they remain mutually incompatible and in permanent contest and competition with each other? Or shall we eventually see some morphing and flexing of the established regulatory systems such that they begin to radically internalise both the ecological and the metabolic negative effects and externalities? That is, shall we see whole system change towards an ecological and nutrition centred food policy (as advocated by some expert groups now in Brussels (e.g. Food 2030; IPES). Also, shall we begin to see, as our first empirical researches suggest here in this special section of Food Security, the growth of new food assemblages playing an increasingly significant role in re-building Europe’s FNS systems through both local and translocal processes and practices?

What seems more than likely as a significant backdrop to these questions is that there will be a continuous decline in state welfare spending which in itself will provide a critical and fertile basis for the further proliferation of new food assemblages - a shift of responsibility from the state in its conventional guise to the civic and local community sectors. The question will be – as we shall see in many of the succeeding papers - that this is putting an emphasis upon more reflexive and innovative state support systems, perhaps at place-based levels. In order for the new food assemblages to become more empowered and potentially transformatory therefore, our evidence suggests several areas of action and opportunity, which need to be addressed.

First, there needs to be far more recognition and opportunity for these assemblages to be brought into and made part of the central decision-making structures of the existing multi-level, state-based regulatory and policy frames. This means, as we see in the case of the Welsh Government (see the paper by Ana Moragues Faus and Bridin Carroll [this issue]), the recognition and prioritisation of food poverty alleviation as an area of government action. The government has funded the Community Food Co-operative programme and created a Food Poverty Alliance. At the EU level, discussions are now taking place about the next reform of the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP) into a much wider Common Food Policy or Framework. At city municipality levels many authorities (e.g. London, Rotterdam and Rome) are embracing food policy councils and are now setting sustainable food targets. Hence a key empowering and potentially transforming process involves the proactive participation of assemblages as part of more reflexive, strategic and deliberative food governance.

Second, a major challenge is to enrol conventional farmers and their unions into the food sustainability and security debates and policy framings. This is a recognisable major challenge and obstacle as the majority of farmers are still highly dependent upon the conventional regulatory regimes outlined above. They are dependent on retail and catering corporates for their price and quality settings; and far too many are also still highly dependent upon EU state subsidies. It is thus not surprising that they feel alienated from many of the sustainable and food security movements given their ‘locked-in’ and dependent status on these historically reliable regulatory systems. BREXIT in the UK and the debates about potential radical reform of the EU CAP after 2020 may be a political opportunity to unify the farming lobbies with the alternative food movements, and to significantly modernise agricultural policy along a wider set of food and nutritional security principles associated with quality food provision, bio-diversity enhancement and health and well being.

Third, a major government role needs to create and encourage new forms of both physical and social infrastructures - what we term the ‘missing middle’ – which are currently the weakest links in creating the transformative potential of new food assemblages. This means creating more physical hubs for the more distributed rather than concentrated nature of their food networks and shorter supply chains. Alternative food assemblages are distinguished partly by their distributed (rather than concentrated) geographies of production, processing and consumption. They do not abide by the same centralised and scalar logics as the retailer-led logistical and concentrated chains. Thus far, many suffer getting goods to market, or meeting urban consumers demands. In addition, government bodies also tend to prefer to deliver and fund programmes and procurement contracts to large and concentrated delivery agents, rather than groups of smaller and distributed actors. This is particularly a problem for the much-needed growth in fruit and vegetable production and supply, which not only requires local and distributed levels of pump-priming funding, but also a more diverse set of wholesaling, retail and consuming outlets.

Finally, it is important for established government agencies at all levels to begin to collaborate in reflexive visioning of the future food systems in their areas and regions, and to create platforms for the bringing together of actors in all of the governance arenas we have explored in the TRANSMANGO project. The paper in Ecology and Society by Hebinck et al. 2018 reflexively summarizes the experiences and inherent societal problems with foresight exercises for planning transformative changes in food systems. There is some evidence at the UN, EU and city and regional levels that such spaces of deliberation are beginning to be enacted (i.e. in Eindhoven, Tuscany and Dar es Salaam). So far, however, our research evidence suggests that the proliferation of alternative assemblages have yet to reach a point or to have the necessary ‘design principles’ whereby they can enter with confidence and legitimacy the established governance arena.

In order to do this it will be necessary to enrol politicians as well as government officers into the arenas of alternative and new food politics. Forms of coalition-building and future visioning become important for the alternative assemblages, almost because, by their nature, they can be seen as fragmented and in competition with one another. Some level of translocal coordination between a range of different assemblages become an important challenge, as we have seen in our analysis of sustainable food in city networks and community food co-operatives. Government support is needed in fostering these coordinating mechanisms, as in the creation of national and regional food policy councils.

All of this takes political will and requires recognition on the part of established state structures that they can no longer marginalise food policy concerns or ring-fence them under narrow sectoral or scientific specifications. The rise of alternative food assemblages in Europe, especially since 2007–8, (see below) needs to be seen as far more than potentially and palliatively ‘filling in the gaps’ in responsibility left by the established and less effective governance frameworks outlined here. As has already been shown, these assemblages articulate a far more holistic, diverse, ecologically sound and nutritionally robust set of principles around which the synergies among food security, sustainability and sovereignty can again be recreated and actively re-connected. In order for this to be truly transformative it will involve a pragmatic re-organisation of the rules, regulations and eventually power relations. Critical here will be the rising legitimacy of new collaborations and coalitions between both producer and consumer interests and actors, and more reflexive governance processes and structures which are confident enough to allow such assemblage voices and the power to re-design and re-build food futures.

4 Theoretical and methodological entry points for locating transformation: assemblages

The thrust of TRANSMANGO has, from the start, been to perceive the European food ‘system’ not as uniform but as highly fragmented. Such fragmentation unfolds, and has unfolded over time, as different configurations in which food is produced, procured, distributed and consumed. These configurations are theoretically and methodologically conceptualised as assemblages. Assemblage theory, (as set out by Deleuze and Guattari 1987), provides inspiration for an analysis of a range of food related actor projects which not only co-exist but also periodically interact, giving shape and content to multi-level transformations at ‘local’ level, in municipalities, in the countryside, etc. that, when aggregated, potentially stand to reshape the European food system or regime as a whole.

This is, indeed, the main postulate of this special section of the journal. Food-associated assemblages appear potentially as platforms of transformation, distinguished as sites where a rebuilding of the food system takes place. Assemblages are seen as composed of heterogeneous elements that may be human and/or non-human, organic and inorganic, technical and natural (Anderson and McFarlane 2011:124). Assemblage theory is thus an attempt to go beyond the social per se: to include the material as objects of study and to explore how social actors engage the material (e.g. food, markets, infrastructure, transport systems and logistics). Assemblages thus stand for – in our case – those associations of practices and relationships concerned with the production, consumption and distribution of food, connecting consumers with producers and processors of food, as well as town and country-side, and more generally the global with the local. Typical of food assemblages is a continuous reassembling of old and new ideas and the reassembling of resources in many different ways.

We follow Li (2007:265) in her definition of reassembling as the ‘grafting of new elements and reworking of old ones; employing existing discourses to new ends’. Assemblages are fertile grounds capable of continuously generating ‘new’ practices and new hybrid human and non-human actor projects. More specifically, socio-material and natural realities and practices are reassembled to form new expressions that did not exist before. Part of the complexity – and our challenge – that emerges from this is argument is showing empirically that the actual process of reassembling does not follow a single logic or one master plan. Such an approach, we find, allows for an improved theorisation and empirical underpinning of the current (post 2007) fragmented European foodscape, as constituted by new patterns of connecting and/or reconnecting resources in new ways, leading to new routines and patterns as well as new social relationships.

Thus the more fragmented food landscape in Europe and elsewhere are approached as being constituted of a range of often contrasting assemblages that co-exist and interact with one another; continuously producing new assemblages. The fragmented food landscape is hypothesised as being stretched between two extremes, which find their expressions also at the ideological level and are legitimised by ideologically ‘opposing’ stakeholder groups: supermarkets and big corporate food multinationals (Nestlé, Unilever, AHold-Delhaize, Woolworth, Carrefour, Walmart) referred to as Empire by Van Der Ploeg (2010); versus local and translocal ‘alternative’ food networks and movements allied to, for instance, Via Campesina (Martínez-Torres and Rosset 2014).

At the level of discourse and networks these are separate and barely interacting assemblages that hardly share a common view on the future of food and sustainable development. These assemblages are well researched and described in the literature as well as being addressed in the reports of expert committees such as the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE) and The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB). Assemblages driven by corporate interest groups clearly hinge on continuous and new rounds of industrialisation of food production and consumption and can be captured as such. This modernisation of the food security paradigm argues for modern, scientifically sound production technologies, efficient in terms of resource use, market driven, cheap and efficient marketing systems, combining spaces of (cheap) production with those of consumption. These are often centrally organised and vertically coordinated (e.g. up- and down-stream of the farm enterprise). These assemblages truly span the globalising world and at the same time perform in such a way that they produce a globalising world. Cures for problems are found in fine-tuning the modern food system (Marsden 2017). A second, contrasting paradigm to attain food security centres around agro-ecological principles of regional food sovereignty, autonomy of production and consumption, shorter regional oriented food networks, driven by different and often more horizontally organised and poly-centred markets(Altieri and Toledo 2011; Hebinck et al. 2015).

The assemblages that were researched in the various European countries of TRANSMANGO (Latvia, Finland, Belgium, The United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain) were purposely and systematically selected such that certain key transformations and rebuilding attempts would be captured. This selection process followed in-depth national analyses of FNS in each country, a media analysis demonstrating the variable rise of FNS concerns since 2007; and a more detailed Delphi survey and analysis of key European stakeholders focussing on their understanding of FNS (see Moragues-Faus et al. 2017). The eventual selection of assemblage cases were clustered as follows: (1) those assemblages that focussed on re-enforcing food entitlements of traditional and newly emerging vulnerable groups; (2) those assemblages clearly attempting to re-connect sustainability and health, and (3) those that attempt rebuilding food systems through fostering new and novel urban-rural synergies. Through this clustering TRANSMANGO researchers were able to identify a series of assemblages where active rebuilding of the food system was on-going. These were later regrouped and subdivided as follows: (a) Assemblages that have a common agenda for addressing food entitlements though various forms of food assistance. Food banks and related agencies and actor configurations play central but, as we shall see, varying roles; (b) Assemblages where social struggles to access productive resources such as land play a constituent role. These assemblages are best labelled as (peri-) urban land-access movements; (c) A third set of assemblages hinge on (increasing) consumer-citizen commitment which has become a regular feature, and again expressed in different ways. This includes urban food project and city food councils; and (d) A final set of assemblages that were found relevant for our objectives deal with public procurement and aspects of preparedness. These kinds of assemblages are captured by public catering as well as by school feeding projects.

5 This special section of food security

This introduction is followed by a series of empirically-based articles that analytically address the aforementioned assemblages. Hebinck and Oostindie elaborate in some detail the theoretical and methodological foundation for exploring FNS-assemblages that have emerged in the European food landscape. They position their paper vis-a-vis the food security literature and strands in the food literature, which emphasise that continued and extended modernisation is required to address food poverty and insecurity. Their innovative contribution is to conceptualise the assemblages as evolving around the creation of novel governance arrangements. They argue that the assemblages emerged as concrete responses to a (gradual but definitive) retreat of the welfare state as part of neo-liberalisation and globalization tendencies and its closely associated expansion of different types of FNS vulnerabilities. Their paper sets the tone for most of the other papers in this special section of Food Security.

Pedro Cerrada-Serra et al. focus on social struggles as key aspects of food assemblages. The struggle for land access is particularly important in order to be able to engage in urban agriculture, and this is central to new forms of production for addressing food related entitlements - an essential for coming to grips with what urban agriculture means for food poverty.

Ana Moragues Faus and Bridin Carroll reflect in their contribution on the integrative plans and urban food governance approaches. In order to understand these policy trajectories they mobilise a political ecology framework to explore how the specific configurations of nature and society express themselves in the processes and outcomes of urban food policies. Drawing on the experiences of two European cities (Cardiff and Cork) they argue that sustainable food transitions are conditioned by the specific socio-ecological configurations of individual cities.

The paper by Francesca Galli et al. explores food assistance as examples of assemblages that span multi-sector collaborations among public, private and civil society institutions. They argue that food assistance initiatives succeed in bringing together institutions, organisations and civil society in order to address food poverty in novel ways - pursuing a systems approach to the analysis of governance relations in food assistance across different countries. Data for their analysis is from Italy, the Netherlands and Ireland.

Pedro Cerrada-Serra et al. explore in various empirical and socio-political contexts the role of so-called alternative food networks. Drawing on data from Belgium, Spain and the United Kingdom, they set out to establish new linkages between food security debates and the critical AFN literature. Inspired by new food security concepts, they propose a location-based approach to food security as a useful starting point to assess AFNs’ links with food security outcomes. In this way they strive to overcome the limitations of food security conceptual frameworks, which tend to be locked into fixed levels of scale and generalised, as well as oppositional assumptions.

The article by Mikelis Grivins et al. takes school meals as an entry point to explore the void between policies and regulations. Drawing on empirical material from Latvia and Finland, they offer a conceptual model that helps to re-establish the links between the regulated elements of the food system. They show in detail how the separate regulations are aligned and what difficulties emerge in developing and implementing school meal provision as part of complex food policy.

Andre Deppermann et al. analyse market impacts resulting from a much wanted switch to regionally produced feed in the European livestock sector. They use simulation models to show that regionalisation and shortening of the food supply chain will have strong impacts on prices for livestock products in Europe. This is in turn will significantly increase livestock production costs.

Jessica Duncan and Priscilla Claeys analyse global food governance processes which were given a boost by the reform of the World Food Security Council (CFS) in 2009. Participation of “stakeholders” and an explicit commitment to advancing human rights and prioritizing the voices of those most affected by hunger and food insecurity marked the new governance that holds promise for food security globally and locally. They argue that the new architecture of global food security governance has evolved in an increasingly anti-political way; one that is increasingly organized to minimise, avoid, or conceal the relations of power and conflictual dimensions inherent in complex and normative policy processes and reflective of the antagonisms inherent in human society. Through the reform process, however, they argue that the CFS has emerged as a forum where politics can, and do, play out. Supporting this role requires supporting the CFS as a political committee.

Overall, the collection of papers demonstrates how new dynamic coherences and infrastructures are forming out of the food crisis and the fragmented European food system. This is a process of re-building in two senses: first, by crossing old boundaries of governance, space and material practices in ways which disrupt established producer-consumer relations and creating new spaces for the possibility of sustainable and nutritional progress; second, by demonstrating the need for a conceptual rebuilding, one which re-assembles the social and material elements of food itself and the very ‘security’ of its supply.

Notes

This wider and combinational set of negative externalities have been documented in our earlier papers and progress reports which include the results of national surveys, media analyses and Delphi studies. See the website for the research reports and deliverables: http://www.transmango.eu/publications.

References

Altieri, M., & Toledo, V. (2011). The agroecological revolution in Latin America: rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38, 587–612.

Anderson, B., & McFarlane, C. (2011). Assemblage and geography. Area, 43, 124–127.

Beddington, J. R., Asaduzzaman, M., Clark, M. E., Fernández Bremauntz, A., Guillou, M. D., Howlett, D. J. B., Jahn, M. M., Lin, E., Mamo, T., Negra, C., Nobre, C. A., Scholes, R. J., Van Bo, N., & Wakhungu, J. (2012). What next for agriculture after Durban. Science, 335, 289–290.

Busch, L (2007) Performing the economy, performing science: from neo-classical to supply chain models in the agri-food sector. Economy and Society, 36(3), 437–466

Clapp, J. (2016). Food (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Constance, D., et al. (2015). Alternative Agri-food movements: patterns of convergence and divergence. Emerald: Research in Rural Sociology and Development Series.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Geels, F., & Schot, J. (2007). Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy, 36(3), 399–417.

Goodman, D., et al. (2012). Alternative food networks. London: Routledge.

Grin, J., et al. (2012). Transitions to sustainable development. London: Routledge.

Hebinck, P., Mango, N., & Kimanthi, H. (2015). Local maize practices and the cultures of seed in Luoland, West Kenya. In J. Dessein, E. Battaglini, & L. Horlings (Eds.), Cultural sustainability and regional development: Theories and practices of territorialisation (pp. 206–219). London: Routledge.

Hebinck, A., Vervoort, J., Hebinck, P., Rutting, L., & Galli, F. (2018). Imagining transformative futures: participatory foresight for food systems change. Ecology and Society, 23, 16.

Horlings, I., & Marsden, T. K. (2012). Towards the real green revolution? Exploring the conceptual dimensions of a new ecological modernisation of agriculture that could feed the world. Global Environmental Change, 21, 441052.

House of Commons (2013). Food Security: Second Report of Session 2014-14. House of Commons. Westminster: London.

Lang, T. (2010). Crisis? What crisis? The normality of the current food crisis. Journal of Agrarian Change, 10, 87–97.

Li, T. (2007). Practices of assemblage and community forest management. Economy and Society, 36, 263–293.

Marsden, T. K. (2013). Sustainable place-making for sustainability science: the contested case of Agri-food and urban-rural relations. Sustainability Science, 8(2), 213–222.

Marsden, T. K., & Morley, A. (2014). Sustainable food systems: building a new paradigm. London: Earthscan/ Routledge.

Marsden, T. K., et al. (2010). The new regulation and governance of food: beyond the food crisis. London: Routledge.

Marsden, T., (2017). Agri-food and rural development: sustainable place-making. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Martínez-Torres, M., & Rosset, P. (2014). Diálogo de saberes in La Vía Campesina: food sovereignty and agroecology. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 41, 979–997.

McFarlane, C. (2009). Translocal assemblages: space, power and social movements. Geoforum, 40, 561–567.

Moore, J. (2015). Capitalism and the web of life. New York: Verso.

Moragues-Faus, A., Sonnino, R., & Marsden, T. (2017). Exploring European food system vulnerabilities: towards integrated food security governance. Environmental Science and Policy, 74, 184–215.

Pretty, J. (2013). The consumption of a finite planet: well-being, convergence, divergence and the nascent green economy. Environmental and Resource Economics, 55, 475–499.

Rip, A., & Kemp, R. (1998). Technological change. In S. Rayner & E. L. Malone (Eds.), Human choice and climate change- resources and technology (pp. 327–399). Columbus: Batelle Press.

Spaargaren, G., et al. (Eds.). (2012). Food practices in transition. London: Routledge.

The Food Foundation (2015) Force-fed: Does the food system constrict healthy choices for typical British families? London

van der Ploeg, J. D. (2010). The food crisis, industrialized farming and the Imperial regime. Journal of Agrarian Change, 10, 98–106.

Wiskerke, J. S. C. C. (2015). Urban Food Systems. In H. de Zeeuw & P. Drechsel (Eds.), Cities and agriculture: Developing resilient urban food systems (pp. 1–25). London: Routledge.

Wright, W., & Middendorf, G. (Eds.). (2008). The Fight over Food : producers, consumers, and activists challenge the global food system. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marsden, T., Hebinck, P. & Mathijs, E. Re-building food systems: embedding assemblages, infrastructures and reflexive governance for food systems transformations in Europe. Food Sec. 10, 1301–1309 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0870-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0870-8