Abstract

The progressive contamination of food products by mycotoxins such as zearalenone (ZEN) has prompted the search for specific substances that can act as protectors against an accumulation of these toxins. This paper discusses the effect of selenium ions and 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) as non-organic and organic compounds that preserve human lymphoblastic cells U-937 under ZEN stressogenic conditions. Based on measurements of cell viability and a DAPI test, concentrations of ZEN at 30 μmol/l, Se at 2.5 μmol/l and EBR at 0.005 μmol/l were selected. The addition of both protectors resulted in an increase in the viability of ZEN-treated cells by about 16%. This effect was connected with a decrease in lipid peroxidation (a decrease in the malonyldialdehyde content) and the generation of reactive oxygen species, which were determined by a cellular ROS/superoxide detection assay and the SOD activity. The Se protection was observed as the blocking of the all excess ROS, while the EBR action was mainly concentrated on something other than the superoxide radical itself. The experiments on the model lipid membranes that mimic the environment of U-937 cells confirmed the affect of ZEN on the structure and physicochemical properties of human membranes. Although the presence of both Se and EBR reduced the effect of ZEN by blocking its interaction with a membrane, the action of Se was more evident.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The contamination of plants, especially cereals, which serve as a food source for animals and humans, by mycotoxins is a global problem. Detoxification of plants is difficult because mycotoxins can be absorbed by crops during all of their growth phases and even after harvesting (Kumar et al. 2008). Mycotoxins, which are taken up together with plant nutrients, are then accumulated in the cells of animals and people, which pose serious hazards to their health (Negedu et al. 2011). The expression of their toxicity is regulated by factors such as age, sex, species and the status of the nutrition of contaminated animals (Hook and Williams 2004). Laboratory observations that have been performed on mice, rats, guinea pigs, hamsters and rabbits have shown that the effects of toxins are associated with many physiological changes in their organs, which can even lead to developing cancer (Belhassen et al. 2015; Creppy 2002; Osweiler 2000). It was found that the liver and kidneys were the predominant tumour sites (Banu et al. 2009; Bray and Ryan 1991). Other studies have indicated that there are additional toxic effects that are connected with immunity suppression, dysfunctions of mitochondrial DNA and the induction of anaemia, which are a consequence of a reduced oxygen supply to tissues (Akande et al. 2006; Aydin et al., 2007; Verma et al., 2004). Moreover, it was suggested that these substances may also affect the structure of the central nervous system (Laag and Elaziz 2013).

One of the mycotoxins that is currently being studied intensively is zearalenone (ZEN, F-2 toxin), which is produced by several species that infect Fusarium, especially cereals such as wheat, oats and barley, which are still the most common food crops in the world (Zinedine et al. 2007). Studies of the mechanism of ZEN action, which have been conducted in in vitro conditions for both animal and human cells, have shown that the effects of its cytotoxicity were mainly due to oxidative stress, which initiated lipid peroxidation (Gautier et al. 2001) and/or oxidative damage of DNA (Verma et al., 2004; Hassen et al. 2007; Tatay et al. 2016). Lipid degradation alters the structure and function of the cellular membrane and inhibits cellular metabolism, which leads to cytotoxicity. The inhibition of protein and DNA syntheses results in the perturbation of the progression of the cell cycle (Abid-Essefi et al. 2004), which induces DNA fragmentation and micronuclei production (Ouanes et al. 2003) and, as a result, leads to apoptosis. However, as was described by Abid-Essefi et al. (2004), the cytotoxicity of Fusarium toxins on epithelium cell lines is concentration- and time-dependent.

Many strategies can be undertaken to reduce the accumulation of mycotoxins in both crops and farm animals, including the use of absorbent materials, which may bind mycotoxins (Wageha et al. 2010) or supplementation with chemicals in order to reduce the stress-inducing effects of ZEN, e.g. quercetin (Escriva et al. 2017). In our earlier studies, we observed that selenium ions and brassinosteroids (24-epibrassinolide; EBR) may serve as protectors that diminish the uptake of ZEN by plant cells (Filek et al. 2017; Kornaś et al. 2018). Plant supplementation with Se has mainly been studied in respect to providing protection against heavy metal stresses. It was suggested that the defence against antioxidative damage of cells is involved in the mechanism of its action (Sieprawska et al. 2015). For mammalian cells, this microelement was indicated as an inhibitor of tumour cell growth in many studies (Batist et al. 1986; Spyrou et al. 1996; Stewart et al. 1997). Brassinosteroids (BRs) have also been examined as potential anticancer and antioxidative factors. It was shown that when used at micromolar concentrations, natural BRs can inhibit the growth of human cancer cell lines (Malíková et al. 2008) and reduce the levels of intracellular reactive oxygen species (Carange et al. 2011).

In the presented experiments, the human cell line U-937 was examined to investigate its potential Se/EBR effects against ZEN stress. A stable cell line enables observations of monocyte cell behaviour in vitro and has been used as a model of the cytotoxicity of a substance against the human immune system in many studies (Gomez et al. 1993; Park et al. 2002; Barbasz et al. 2017). Because they are widely distributed cells that are present in the blood and tissues, they come into contact with “foreign” substances such as, for example, xenobiotics like mycotoxins. This interaction should promote and modulate cells in the course of an immune response. The possibility of using both protectants against ZEN-stress in U-937 cells was demonstrated by analyses of the differences in: (i) the destruction of cell viability, (ii) the generation of cellular ROS/superoxide radicals, (iii) the stimulation of the antioxidative enzymes and (iv) the modification of membrane structures. Changes in the membrane properties that resulted from lipid oxidation were examined as an increase in the MDA concentration, which is generally considered to be an index of ROS membrane degradation (Tomita et al., 1990). Moreover, in the model membranes, which were built from the lipids that were present in the largest quantities in the studied cells, the specific interactions of the tested substances were also considered.

Materials and methods

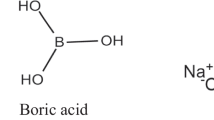

Chemicals

The ZEN was obtained from Fermentek (Jerusalem, Israel). The 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, 24-epibrassinolide (24-epibrassinolide, (22R, 23R, 24R)-2α,3α,22,23-tetrahydroxy-24-methyl-B-homo-7-oxa-5α-cholestane-6-one), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide, 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, bovine serum albumin, cytochrome C, EDTA, Griess reagent (modified), NADH, sodium selenate, thiobarbituric acid, trichloroacetic acid and xanthine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany). The 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (DOPG) were obtained from Avanti© Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). The chloroform, dimethyl sulfoxide and pyruvic acid were from POCH (Gliwice, Poland). The Cellular ROS/Superoxide Detection Assay Kit was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK).

Cell cultures

The human histiocytic lymphoma cell line U-937 (ATCC) was cultured in a suspension in RPMI 1640 containing 5% fetal bovine serum and penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml). Solutions of ZEN at concentrations of 1–300 μmol/l, Na2SeO4 (hereinafter referred to as Se) at concentrations of 0.5–30 μmol/l and EBR at concentrations of 0.1–100 nmol/l were tested. Based on the experiments of cell viability, the concentrations of ZEN (30 μmol/l), Se (2.5 μmol/l) and EBR (0.005 μmol/l) were selected.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using a colourimetric MTT ((3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay. Cells were cultured in 96-well plates with 0.2 × 106 cells per well at a volume of 0.2 ml/well. After 24 h of exposing the cells to selected factors, 50 μL of a MTT solution at a concentration of 5 mg/l was added to each well and left for 2 h at 37 °C. Next, the entire volume of the wells was transferred into Eppendorf tubes (1.5 ml) and then, 0.4 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to the Eppendorf tubes. After 5 min, the solutions were centrifuged and the absorbance of the supernatants was read at a wavelength of 570 nm on an Epoch microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

DAPI staining

In order to investigate the fragmentation of nuclei, 1 × 106 cells in a 0.5-ml suspension were treated with 30 μmol/l ZEN for 24 h with or without Se (2.5 μmol/l) or EBR (5 nmol/l) and the suspensions were prepared on slides and then stained with 1 μg/ml 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (DAPI-DNA complex Ex = 364 nm; Em = 454 nm). The morphology of a nucleus was observed using a Canon EOS 60D camera and a Delta IB-10 optical microscope set with a U filter (420 nm).

Nitric oxide production

The cells were cultured in 24-well plates with 1 × 106 cells per well at a volume of 0.5 ml/well. The cells were treated with the selected factors, adjusted to a final volume of a suspension equal to 0.5 ml and kept for 24 h. After the treatment, the supernatants were collected, centrifuged (1000×g, 5 min) and stored at − 20 °C. The nitric oxide (NO) production from the treated cells was quantified spectrophotometrically using a Griess reagent (modified) (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany). The absorbance was measured at 540 nm and the nitrite concentration was determined using a calibration curve.

Cell membrane damage

A lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was used as the marker of the entire cell membrane. The LDH activity was measured indirectly spectrophotometrically using a Thermo Scientific UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Waltham, MA, USA). This test is based on the ability of LDH to convert lactic acid into pyruvic acid and vice versa. LDH occurs in the cytoplasm of all cells and when the cell membrane is damaged, it is released into a culture medium. Pyruvic acid reacts with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, which leads to the formation of a coloured hydrazone. The amount of colour that is formed is proportional to the number of lysed cells. The cells were cultured in 24-well plates with silver nanoparticles with 0.3 × 106 U-937 cells. After the treatment, the samples were collected and centrifuged (1000×g, 5 min, MPW-351RH) (MPW Med. Instruments, Warsaw. Poland). One hundred microliters of supernatant was added to the tubes containing 0.5 ml of 0.75 mmol/l pyruvate and 10 μl NADH (140 μmol/l) (heated at 37 °C for 10 min) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, 0.5 ml of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine was added. After 1 h, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Determination of the MDA concentration

Membrane lipid peroxidation was estimated using a thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reaction with malondialdehyde (MDA). The cells were cultured in 24-well plates with 2 × 106 U-937 cells per well at a volume of 0.5 ml. After the treatment, the samples were collected and centrifuged (1000×g, 5 min). Vortex and 0.5 ml of 0.5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) were added to the pellets, for 1 min and then lysed by sonicating for 5 min. After centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 min, 0.4 ml of the supernatant was added to the 1.25 ml 20% TCA with 0.5% TBA and heated in a dry thermoblock (100 °C) for 30 min. After cooling, the absorbance was measured at 532 nm and corrected for any non-specific background by subtracting the absorbance at 600 nm. The MDA concentration was calculated using the molar excitation coefficient of 155 mmol/cm.

Cellular ROS/superoxide radicals assay

Free radicals and other reactive species were detected using a Cellular ROS/Superoxide Detection Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). In a 0.5 ml suspension, 1 × 106 cells/ml were incubated with 30 μmol/l ZEN for 24 h with or without Se (2.5 μmol/l) or EBR (0.005 μmol/l) and with a ROS/Superoxide Detection Mix for 30 min at 37 °C. The positive control was incubated with 0.2 mmol/l pyocyanine. After washing, superoxide (red) and oxidative stress (ROS, green)-positive cells were observed using a Canon EOS 60D camera (Tokyo, Japan) and a Delta IB-10 optical microscope set (Poland) with a B (520 nm) and G (590 nm) filter and fluorescence set (× 200 magnification).

Superoxide dismutase assay

Total superoxide dismutase activity (SOD; EC 1.15.11) was assayed according to the spectrophotometric cytochrome method. Of cells, 1 × 106 was homogenised in a 0.05 mol/l phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 0.1 mmol/l EDTA and 0.1% bovine serum albumin. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min. at 10,000×g. The reaction mixture consisted of a phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 0.1 mmol/l EDTA, 0.1 mmol/l cytochrome C and 0.1 mmol/l xanthine. Next, xanthine oxidase and supernatant were added. The absorbance was measured for 2 min at λ = 550 nm. It was expected that a unit of activity (one unit, one unit of cytochrome) would correspond to the amount of enzyme that caused a 50% inhibition of the reduction of cytochrome C at 25 °C. All of the measurements were carried out using a Thermo Scientific UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Waltham, MA, USA). The activity of SOD was expressed relative to the protein content in the supernatant. Protein was assessed by the method of Bradford (1976) using BSA as the protein standard.

Langmuir technique for measuring the model membrane structure

The experiments were performed using the Langmuir technique (Minitrough, KSV, Espoo, Finland) to assess the physicochemical parameters of the lipid monolayers (Rudolphi-Skórska et al. 2016). Surface pressure (π) was detected using a Platinum Wilhelmy plate connected to an electrobalance with an accuracy of ± 0.1 mN/m. The monolayers were prepared by spreading chloroform solutions of the DOPC/DOPG mixture at a molar ratio of 2:1 on the surface of water or with a Se (2.5 μmol/l) and EBR (0.005 μmol/l) aqueous solution as the subphase. The subphase was redistilled water, which had been purified using a Milli-Q system, with a specific resistance of above 18.2 MQ cm−1. ZEN (30 μmol/l) was added directly into the water phase or into the water with selenate ions. All of the experiments were performed at 25 °C. The monolayers were compressed at a rate of 3.5–4.6 Å2/molecule × min, and the experiments were repeated three or four times to ensure a high reproducibility of the obtained isotherms to ± 0.1–0.3 Å2. The dependence of surface pressure versus the area per lipid molecule (π–A) was the basis for calculating the parameters of the lipid monolayer structure: Alim—the minimum area occupied by a single molecule in a fully packed layer and πcoll—pressure at which a layer collapses and Cs−1—static compression representing the mechanical resistance against the layer compression that provides information on the stability and fluidity of a layer.

Electrokinetic potential of the model membranes

Liposomes were prepared according to the method described in detail by Filek et al. (2002) and Rudolphi-Skórska et al. (2018). The lipid mixture (DOPC+DOPG; 2:1, mol/mol) dissolved in chloroform, covering the wall with a round bottom glass tube in a stream of argon. The dried lipid film was hydrated with water (control—0) and vortexed. In the first experiment, ZEN solutions at 10, 20, 40 and 100 μmol/l were added to the media with liposomes and in the second, the liposomes were introduced into the media with ZEN (30 μmol/l), Se (2.5 μmol/l), EBR (0.005 μmol/l) and the mixture of ZEN with Se and EBR. The electrokinetic potential was calculated from the electrophoretic mobilities using the dynamic light scattering (DLS) method with a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Analytical Ltd., Malvern, UK). The mobility values were converted into electrokinetic potentials using the Smoluchowski equation.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SE. The experiments were repeated at least three times, and each experiment included at least three individual treatments. Data from the various treatments were statistically analysed using the SAS ANOVA procedure, and the mean comparisons were performed using Duncan’s test from PC SAS 8.0. Differences of p ≤ 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

The cytotoxicity of ZEN was dependent on the amounts of this substance in the media and increased when the concentration of this mycotoxin was raised—at above 200 μmol/l of ZEN, all of the cells were dead (Fig. 1a). Relatively low concentrations of Se and EBR were selected based on previous experiments, which were connected with their protective activity in a ZEN-stress action. For Se, in the range of studied concentrations (0.5 to 30 μmol /l), the decrease in cell viability was only about 4% (at more than 10 μmol /l), relative to the control and for EBR, it was about 15% (at more than 20 nmol /l) compared to the control (results not shown). Thus, the following concentrations were selected to study the effect of these substances on cell viability: ZEN at 30 μmol/l, Se at 2.5 μmol/l and EBR at 0.005 μmol/l.

Viability of U-937 cells in media with ZEN (a); the observation of the fragmentation of the nuclei (b) of the untreated U-937 cells (1), cells treated with 30 μmol/l ZEN for 24 h (2), cells treated with Se (2.5 μmol/l) (3) or cells treated with EBR (0.005 μmol/l) (4), with 30 μmol/l ZEN and with Se (2.5 μmol/l) (5), with 30 μmol/l ZEN and with EBR (0.005 μmol/l) (6), analysed using DAPI-standing; induction of inflammation in U-937 cells after a 24-h incubation with ZEN indicated by the secretion of nitric oxide (c)

Microscopic observations (DAPI test) showed that in the presence of ZEN, the number of damaged cells significantly increased (compared to the control) (Fig. 1b). More segmented cell nuclei indicated that their nucleus was significantly damaged. The addition of Se and EBR in the mixture with ZEN reduced the number of damaged cell nuclei.

An analysis of the effect of the tested substances on the initiation of cell inflammation showed that the addition of ZEN and ZEN + Se resulted in an increase of the nitric oxide secretions relative to the control, while in the case of EBR (both, alone and in a mixture with ZEN), the opposite reaction (a decrease in the nitric oxide content in the culture medium) was observed (Fig. 1c).

The study of membrane damage, which was measured using LDH and MDA tests, indicated an increase in the content of these substances under the influence of ZEN when it was added alone (Figs. 2a, b). In the LDH test, the Se ions stimulated a decrease, while EBR intensified the level of LDH compared to the control. When they were added together with ZEN, similar changes were observed in this test as in the case of separate applications. For MDA analysis, when both Se and EBR were applied with ZEN, they induced a decrease in the MDA concentration (compared to ZEN); however, when they were present alone, they increased the amounts of this indicator slightly.

The generation of ROS under the influence of ZEN was demonstrated in the measurements of the activity of the antioxidative enzymes (an increase in the SOD activity) (Fig. 3a) as well as by microscopic observations (Fig. 3b). The addition of Se reduced the SOD activity (for both: alone and in mixture with ZEN) significantly, while EBR did not induce significant SOD changes compared to the control (Fig. 3a). Analysis of the microscopic images enabled the superoxide radicals (orange channel) in the general pool of ROS (the green channel) to be characterised (Fig. 3b). The presence of ZEN increased both the total amount of ROS and, in particular, the level of superoxide radicals. When selenium and EBR were added individually, they did not affect the presence of ROS; only EBR initiated the creation of superoxide radicals. When these substances were mixed with ZEN, there was a significant decrease in the amount of ROS (compared to ZEN). EBR affects the total blocking of all of the ROS, while in the ZEN + Se mixtures, only small amounts of superoxide radicals were found.

Effect of ZEN on the SOD activity (a) and cellular ROS/Superoxide production by U-937 cells after treatment with ZEN with or without Se and EBR compared to the positive control (cells treated with pyocyanine). General oxidative stress was observed in the green channel, while superoxide production was detected in the red channel (b)

In model studies, the effect of the studied substances was observed on the lipid layers that had been built from 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), which is a lipid that is found in the largest quantities in membranes (Vance and Vance, 2008) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (DOPG), which brings a negative charge to the lipid layer that is appropriate to the actual charge that occurs on the surface of the tested cell lines (based on the electrokinetic potential of U-937 cells and liposomes—data described later). Lipid monolayers of DOPC+DOPG (2:1, mol/mol) that formed on the water media to which the examined substances were added are shown in Fig. 4 as the dependence of the surface pressure (π) versus the area of the molecules (A) and the monolayer compressibility (Cs−1) versus π (Fig. 4, insert). The physicochemical parameters of the membrane structures were calculated based on these dependences (Table 1). The presence of ZEN in the water media resulted in an increase in the surface that was occupied by the individual molecules in the monolayer (Alim) and a decrease in the pressure and lipid compressibility (Cs−1) compared to the control (water). Se and EBR (separately) also increased the Alim, although to a lesser extent than those of ZEN. In the mixture with ZEN, there were greater values of Alim than for this substance alone, especially in the case of Se. There was a similar tendency for the other parameters—a decrease in their mixture with ZEN, compared to the values that were obtained for Se and EBR alone as well as an increase compared to ZEN.

The values of the electrokinetic potential of the liposomes that were obtained from the studied lipids depended on the concentration of ZEN in the tested media and increased at about 8 mV when the concentration of this toxin was increased from 10 to 100 μmol/l (Table 2). The presence of selenium in the media resulted in a decrease, while the presence of EBR resulted in an increase in the values of the electrokinetic potential of the liposomes compared to the values under the control conditions (0). The mixtures of ZEN + Se caused the electrokinetic potential to decrease (compared to those that were registered for ZEN alone at 30 μmol/l), whereas for the ZEN + EBR mixture, there was an increase in the tendency of the potential values (Table 3).

Discussion

The studies of the human U-937 cells indicated that an IC50 (the half maximal inhibitory concentration) factor for these cells was 57.09 ± 2.27 μmol/l of ZEN. The same IC50 value for ZEN was found for LO2 hepatocyte cells by Ku et al. (2014). On the other hand, Vero, Caco-2, DOK or HepG2 cells that had been treated with ZEN exhibited features of classical apoptosis at lower ZEN concentrations of 10–40 μmol/l (Abid-Essefi et al., 2004; Ayed-Boussema et al. 2008). The IC50 factor indicates that 50% of the cells were severely damaged and that above this value, cells may be destroyed. Thus, in our studies of the protective effect of Se and EBR against the action of a toxin, a concentration of 30 μmol/l ZEN was selected so that the possible recovery action of these substances were more visible in a higher percentage of cells that had not been destroyed. It was found that both Se and EBR increased the cell viability, while it was decreased in the presence of ZEN.

The ZEN-cytotoxicity was confirmed by an analysis of the LDH leakage assay and the ZEN-induced increase in the extracellular LDH level, which correlated with the number of damaged U-937 cells. Similar observations of a loss of plasma membrane integrity were made for neuronal cells (Venkataramana et al. 2014).

Finding that ZEN stimulated an increase in the MDA content indicates the initiation of membrane lipid oxidation as an effect of the oxidative stress action (Tomita et al., 1990). Changes that result from the oxidative stress that was caused by ZEN were also found in HepG2 and Caco-2 cells (Hassen et al. 2007; Kouadio et al. 2005) as well as in plant cells (Filek et al. 2017; Kornaś et al. 2018). An increase in the ROS concentration, which is a direct indicator and stimulator of oxidative stress, was observed in the presented experiments and the protective effects of Se as well as EBR causing a decrease in the amount of ROS were also observed.

The inclusion of defensive mechanisms against an excess of ROS was demonstrated as an increase in the activity of the antioxidant enzymes. The different reactions of the tested protective substances indicate the activation of various stages of the defence mechanisms. The decrease in the amount of ROS in the presence of Se is associated with a decrease in the SOD activity, which is responsible for the peroxidation of the superoxide anion radicals. This was confirmed by the observation of the total disappearance of the superoxide radicals in the ZEN + Se media. The selenium atom is incorporated into selenocysteine and in this form, it is included into enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase and type I iodothyronine 5′-deiodinase (Rayman 2000). Thus, Se has a significant impact on reducing ROS production. While EBR acts by stimulating the overall antioxidant system, EBR is also involved in the removal of H2O2 as has been demonstrated in earlier studies (Janeczko 2016). Thus, it is probable that the small amounts of superoxide radicals, which were not fully eliminated in the presence of EBR, were observed in the present experiments.

A precise analysis of the effects of Se and EBR on the membrane of the examined cells was performed in model experiments. DOPC, which is the main lipid in human cells, has been used in many studies to explain the first steps of the mechanisms that are involved in the interactions between various chemicals and membranes (Mosca et al. 2011; Rudolphi-Skórska et al. 2017). In the presented experiments, the mixture of DOPC with DOPG mimicked the physicochemical properties of the native human U-937 cells, which was confirmed by the measurements of the electrokinetic potential of the model and natural cells. There was a significant increase in the Alim value (by about 30% compared to the control), a decrease in πcoll and an almost 40% decrease in Cs−1 (compression module that indicates a decrease in the stiffness of the layer) in the presence of ZEN, which confirms the possibility that this toxin may also be found in human cell membranes. Such an assumption was proposed in the studies of the ZEN interaction with model plant cells (Gzyl-Malcher et al. 2017). When ZEN is incorporated into the monolayers, it decreases their stability and stiffness. The presence of Se and EBR in the mixture with ZEN partially reversed the influence of ZEN on the physiochemical properties of membranes. The larger Se effect compared to EBR on the modification of the membrane structure that was observed in the present experiments may result from differences in the interactions of both of these substances with the membranes. As was demonstrated in previous experiments, the presence of Se influences the modification of the structure of the molecules in the hydrophilic layer of lipids (Gzyl-Malcher et al. 2017), while EBR can also penetrate the hydrophobic part (such as ZEN and other hydrophilic-hydrophobic compounds) (Filek et al. 2018).

Based on the presented experiments, it can be concluded that ZEN exhibits cytotoxic activity against human U-937 cells with an IC50 equal to 57.09 ± 2.27 μmol/l. The addition of Se at 2.5 μmol/l and EBR at 0.005 μmol/l protects against the cytotoxic action of ZEN. Their protective mechanism is related to decreasing the production of ROS, which is stimulated in the presence of ZEN. Se reduces the ROS excess and thus prevents membrane lipid peroxidation and damage to the cells (measured as a decrease in LDH leakage), while the effect of EBR is based on an enhancement of the ability of cells to cope with the consequences of oxidative stress. This study of model membranes enabled the physicochemical parameters of lipid structure of U-937 cells to be precisely described. It was found that the destabilising effect of ZEN on lipid organisation in the membranes was “reversed” by both of the studied substances but to a greater extent in the presence of Se.

Abbreviations

- BRs:

-

Brassinosteroids

- DLS:

-

Dynamic light scattering

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- DOPC:

-

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DOPG:

-

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol)

- EBR:

-

24-epibrassinolide

- GM-CSF:

-

Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- IFN-γ:

-

γ-Type interferon

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- iNOS:

-

Nitric oxide synthase

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- MTT:

-

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- NBT:

-

Nitroblue tetrazolium

- PMA:

-

Phorbol esters, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- RA:

-

Retinoic acid

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase activity

- TNF-α:

-

Tumour necrosis factor α

- TPA:

-

12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- VD3:

-

Cholecalciferol, vitamin D3

- ZEN:

-

Zearalenone

References

Abid-Essefi S, Ouanes Z, Hassen W, Baudrimont I, Creppy E, Bacha H (2004) Cytotoxicity, inhibition of DNA and protein syntheses and oxidative damage in cultured cells exposed to zearalenone. Toxicol in Vitro 18:467–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2003.12.011

Akande KE, Abubakar MM, Adegbola TA, Bogoro SE (2006) Nutritional and health implications of mycotoxins in animal feeds: a review. Pak J Nutr 5:398–403

Aydin A, Erkan ME, Başkaya R, Ciftcioglu G (2007) Determination of aflatoxin B “1” levels in powdered red pepper. Food Control 18:1015–1018

Ayed-Boussema I, Bouaziz C, Rjiba K, Valenti K, Laporte F, Bacha H, Hassen W (2008) The mycotoxin zearalenone induces apoptosis in human hepatocytes (HepG2) via p53-dependent mitochondrial signaling pathway. Toxicol in Vitro 22:1671–1680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2008.06.016

Banu GS, Kumar G, Murugesan AG (2009) Ethanolic leaf extract of Trianthema portulacastrum L. on aflatoxin induced hepatic damage in rats. Indian J Clin Biochem 24:250–256

Barbasz A, Oćwieja M, Walas S (2017) Toxicological effects of three types of silver nanoparticles and their salt precursors acting on human U-937 and HL-60 cells. Toxicol Mech Methods 27:58–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376516.2016.1251520

Batist G, Katki AG, Klecker RW, Myers CE (1986) Selenium-induced cytotoxicity of human leukemia cells: interaction with reduced glutathione. Cancer Res 46:5482–5485

Belhassen H, Jiménez-Díaz I, Arrebola JP, Ghali R, Ghorbel H, Olea N, Hedili A (2015) Zearalenone and its metabolites in urine and breast cancer risk: a case-control study in Tunisia. Chemosphere 128:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.12.055

Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254

Bray GA, Ryan DH (1991) Mycotoxins, cancer and health. Louisiana State University Press, 1991

Carange J, Longpré F, Daoust B, Martinoli MG (2011) 24-Epibrassinolide, a phytosterol from the brassinosteroid family, protects dopaminergic cells against MPP. J Toxicol 2011:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/392859

Creppy EE (2002) Update of survey, regulation and toxic effects of mycotoxins in Europe. Toxicol Lett 127:19–28

Escriva L, Jose Ruiz M, Font G, Manyes L (2017) Effects of quercetin against mycotoxin induced cytotoxicity: a mini-review. Curr Nutr Food Sci 13:240–246

Filek M, Zembala M, Szechyńska-Hebda M (2002) The influence of phytohormones on zeta potential and electrokinetic charges of winter wheat cells. Z Naturforsch C 57:696–704

Filek M, Łabanowska M, Kurdziel M, Sieprawska A (2017) Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy in studies of the protective effects of 24-epibrasinoide and selenium against zearalenone-stimulation of the oxidative stress in germinating grains of wheat. Toxins 9:1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins9060178

Filek M, Sieprawska A, Oklestkova J, Rudolphi-Skórska E, Biesaga-Kościelniak J, Miszalski Z, Janeczko A (2018) 24-Epibrassinolide as a modifier of antioxidant activities and membrane properties of wheat cells in zearalenone stress conditions. J Plant Growth Regul 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-018-9792-0

Gautier JC, Holzhaeuser D, Markovic J, Gremaud E, Schilter B, Turesky RJ (2001) Oxidative damage and stress response from ochratoxin A exposure in rats. Free Radic Biol Med 30:1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00507-X

Gomez MJ, Torosantucci A, Quinti I, Testa U, Peschle C, Cassone A (1993) Mannoprotein-induced anti-U937 cell cytotoxicity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from uninfected or HIV-infected subjects: role of interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α. Cell Immunol 152:530–543. https://doi.org/10.1006/cimm.1993.1310

Gzyl-Malcher B, Filek M, Rudolphi-Skórska E, Sieprawska A (2017) Studies of lipid monolayers prepared from native and model plant membranes in their interaction with zearalenone and its mixture with selenium ions. J Membr Biol 250:273–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00232-017-9958-x

Hassen W, Ayed-Boussema I, Oscoz AA, Lopez ADC, Bacha H (2007) The role of oxidative stress in zearalenone-mediated toxicity in Hep G2 cells: oxidative DNA damage, gluthatione depletion and stress proteins induction. Toxicology 232:294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2007.01.015

Hook SCW, Williams R (2004) Investigating the possible relationship between pink grains and Fusarium mycotoxins in 2004 harvest feed wheat. HGCA Project Report No 354:1–16 Available at: https://cereals.ahdb.org.uk/media/272347/pr354.pdf

Janeczko A (2016) Presence, transport and physiological activity of brassinosteroids in crop plants from Poaceae and Fabaceae family. Monography 17 of the Institute of Plant Physiology Polish Academy of Sciences in Krakow 1–75. Available at: http://ifr-pan.krakow.pl/public/files/misc/files/book_brassinosteroids_aj.pdf

Kornaś A, Filek M, Sieprawska A, Bednarska-Kozakiewicz E, Gawrońska K, Miszalski Z (2018) Foliar selenium-application for protection against the first stages of mycotoxin infection of crops plants leaves. J Sci Food Agric 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.9145

Kouadio JH, Mobio TA, Baudrimont I, Moukha S, Dano SD, Creppy EE (2005) Comparative study of cytotoxicity and oxidative stress induced by deoxynivalenol, zearalenone or fumonisin B “1” in human intestinal cell line Caco-2. Toxicology 213:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2005.05.010

Ku KJ, Liu X, Fang M, Wu YN, Gong ZY (2014) Zearalenone induces oxidative damage involving Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in hepatic L02 cells. Mol Cell Toxicol 10:451–457

Kumar V, Basu MS, Rajendran TP (2008) Mycotoxin research and mycoflora in some commercially important agricultural commodities. Crop Prot 27:891–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2007.12.011

Laag EM, Elaziz HOA (2013) Effect of aflatoxin B “1” on rat cerebellar cortex: light and electron microscopic study. Egypt J Histol 36:601–610. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.EHX.0000432619.75801.15

Malíková J, Swaczynová J, Kolář Z, Strnad M (2008) Anticancer and antiproliferative activity of natural brassinosteroids. Phytochemistry 69:418–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.07.028

Mosca M, Ceglie A, Ambrosone L (2011) Effect of membrane composition on lipid oxidation in liposomes. Chem Phys Lipids 164:158–165

Negedu A, Atawodi SE, Ameh JB, Umoh VJ, Tanko HY (2011) Economic and health perspectives of mycotoxins: a review. J Biomed Sci 5:5–26

Osweiler GD (2000) Mycotoxins: contemporary issues of food animal health and productivity. Vet Clin North Am: Food Anim Pract 16:511–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-0720(15)30084-0

Ouanes Z, Abid S, Ayed I, Anane R, Mobio T, Creppy EE, Bacha H (2003) Induction of micronuclei by zearalenone in Vero monkey kidney cells and in bone marrow cells of mice: protective effect of vitamin E. Mutat Res-Gen Tox En 538:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1383-5718(03)00093-7

Park JE, Yang JH, Yoon SJ, Lee JH, Yang ES, Park JW (2002) Lipid peroxidation-mediated cytotoxicity and DNA damage in U-937 cells. Biochimie 84:1198–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-9084(02)00039-1

Rayman MP (2000) The importance of selenium to human health. Lancet 356:233–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02490-9

Rudolphi-Skórska E, Filek M, Zembala M (2016) α-Tocopherol/gallic acid cooperation in the protection of galactolipids against ozone-induced oxidation. J Membr Biol 249:87–95

Rudolphi-Skórska E, Filek M, Zembala M (2017) The effects of the structure and composition of the hydrophobic parts of phosphatidylcholine-containing systems on phosphatidylcholine oxidation by ozone. J Membr Biol 250:493–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00232-017-9976-8

Rudolphi-Skórska E, Dyba B, Kreczmer B, Filek M (2018) Impact of polyphenol-rich green tea extracts on the protection of DOPC monolayer against damage caused by ozone induced lipid oxidation. Acta Biochim Pol 65:193–195. https://doi.org/10.18388/abp.2018_2612

Sieprawska A, Kornaś A, Filek M (2015) Involvement of selenium in protective mechanisms of plants under environmental stress conditions—review. Acta Biol Cracov Ser Bot 57:9–20

Spyrou G, Björnstedt M, Skog S, Holmgren A (1996) Selenite and selenate inhibit human lymphocyte growth via different mechanisms. Cancer Res 56:4407–4412

Stewart MS, Davis RL, Walsh LP, Pence BC (1997) Induction of differentiation and apoptosis by sodium selenite in human colonic carcinoma cells (HT29). Cancer Lett 117:35–40

Tatay E, Font G, Ruiz MJ (2016) Cytotoxic effects of zearalenone and its metabolites and antioxidant cell defense in CHO-K1 cells. Food Chem Toxicol 96:43–49

Tomita M, Okuyama T, Hatta Y, Kawai S (1990) Determination of free malonaldehyde by gas chromatography with an electron-capture detector. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl 526:174–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4347(00)82495-0

Vance DE, Vance JE (2008) Phospholipid biosynthesis in eukaryotes. In: Vance DE, Vance JE (eds) Biochemistry of lipids, lipoproteins and membranes, 5th edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 213–244

Venkataramana M, Nayaka SC, Anand T, Rajesh R, Aiyaz M, Divakara ST, Rao PL (2014) Zearalenone induced toxicity in SHSY-5Y cells: the role of oxidative stress evidenced by N-acetyl cysteine. Food Chem Toxicol 65:335–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2013.12.042

Verma J, Johri TS, Swain BK, Ameena S (2004) Effect of graded levels of aflatoxin, ochratoxin and their combinations on the performance and immune response of broilers. Br Poult Sci 45:512–518

Wageha AA, Ghareeb K, Böhm J, Zentek J (2010) Decontamination and detoxification strategies for the Fusarium mycotoxin deoxynivalenol in animal feed and the effectiveness of microbial biodegradation. Food Addit Contam 27:510–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/19440040903571747

Zinedine A, Soriano JM, Moltó JC, Maňes J (2007) Review on the toxicity, occurrence, metabolism, detoxification, regulations and intake of zearalenone: an oestrogenic mycotoxin. Food Chem Toxicol 45:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2006.07.030

Funding

This work was supported by the project of National Center of Science (NCN) Poland No. 2014/15/B/NZ9/02192.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Barbasz, A., Rudolphi-Skórska, E., Filek, M. et al. Exposure of human lymphoma cells (U-937) to the action of a single mycotoxin as well as in mixtures with the potential protectors 24-epibrassinolide and selenium ions. Mycotoxin Res 35, 89–98 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12550-018-0334-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12550-018-0334-1