Abstract

Camelid management was a major part of the Wari Empire’s (ca. ad 600–1050) economy; however, it is uncertain whether camelid husbandry was centrally regulated or locally managed. To address this problem, we applied combined isotope ratio analyses (δ13C, δ15N, δ18O, 87Sr/86Sr, and 20nPb/204Pb) to camelid remains from Castillo de Huarmey, a Wari administrative center along the northern Peruvian coast. Results support a mostly local herding scenario, but Sr isotopes indicate that at least three animals were non-local and most likely came from the highlands. Compared to data from two contemporary Wari sites, Cerro Baul and Conchopata, bimodal distribution of δ13C values suggest that regardless of the distinctive geographical and ecological location of these sites, two distinct foddering strategies were practiced, based on only C3 plant diet, or intermixed C3/C4 plants diet. Our data support a dimorphic husbandry model with some herds engaged in grazing on the maize stubble and some herds operating outside arable areas, possibly indicative of short-distance seasonal transhumance. The presence of non-local animals at Castillo de Huarmey underscores the site’s importance with respect to developed trade networks between the coast and the highlands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the Pre-Columbian Andes, the two New World domesticated camelids, llama (Lama glama) and alpaca (Vicugna pacos), served as the primary source for meat, pelts, bone tools, and secondary source with wool for textiles, dung for fuel, and as pack animals (Moore 1989; Bonavia 2008; Thornton et al. 2011). Zooarchaeology has an interest in reconstructing husbandry systems and especially animal diet and mobility, and recently has adapted stable isotope analysis of bone and dental tissues to address important questions with respect to camelid ecology and husbandry (Shimada and Shimada 1985; Miller and Burger 1995; Yacobaccio 2007; Szpak 2013). In this study, we explore camelid management at the archeological site of Castillo de Huarmey, located along the northern coast of Peru, by using multiple isotopic analyses (δ13C, δ15N, δ18O, 87Sr/86Sr, and 20nPb/204Pb) and comparing these data regionally against published data from other Wari sites of Cerro Baul (Thornton et al. 2011) and Conchopata (Finucane et al. 2006).

Cultural and environmental background

The Wari cultural tradition was the first Andean empire to originate prior to the Inca Empire, during the Middle Horizon period, between ca. ad 600–1050 (Isbell and McEwan 1991; Schreiber 1992; Isbell 2008; see overviews in Bergh 2012; Tung 2012; Giersz and Makowski 2014). Its main capital was established at HuariFootnote 1 in the Ayacucho Valley in the central highlands; however, administrative and religious control of hinterland sites was likely managed through regional centers, including Castillo de Huarmey on the north coast of Peru (Giersz and Makowski 2014).

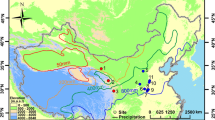

Castillo de Huarmey is located less than 4 km from the Pacific coastline, in the suburbs of the modern city of Huarmey (Figs. 1 and 2), close to the Huarmey River estuary. The Huarmey River is one of many seasonal rivers that originate in the western Andean Cordillera Negra and extend to the Pacific Ocean, passing through the arid Peruvian desert. Adjacent lands may be cultivated by use of artificial irrigation (Giersz 2017). The annual precipitation does not exceed 25 mm/m2 (INRENA report, 2007) and, as a consequence, all water resources in the Huarmey Valley rely on rainfall originating in the Andes and the occasional El Niño event (Sandweiss et al. 2001). At higher elevations in the coastal zone, additional moisture accumulates with winter fog (garúas) which promotes the formation of fog oases (lomas). Their distribution is variable and could expand during El Niño events (Wells and Noller 1999). Vegetation in the coastal zone is mostly xerophytic; therefore, lomas are the only habitats along the coast that do not require irrigation and can be used as pastures. Lomas vegetation possibly occurred within the Huarmey Valley during the site occupation, but upper valley area has not yet been subjected to archeological excavations.

To date, stable isotope analyses of archeological camelid remains have been conducted at two Wari ceremonial centers situated some distance from Castillo de Huarmey: Conchopata (2700 masl) in the Wari heartlands, located near Huari (Finucane et al. 2006) and Cerro Baul with adjacent Cerro Mejía (both 2500 masl) at the southern frontiers of the empire in the Moquegua Valley (Thornton et al. 2011; McEwan and Williams 2012) (Fig. 1). At Conchopata, Finucane et al. (2006) observed two divergent camelid foddering strategies based on δ15N and δ13C results. One group had lower δ13C values (− 19.5 to − 16.8 ‰) and likely consumed almost exclusively C3 plants, while the other group was more 13C-enriched, with higher δ13C values (− 12.1 to − 8.2‰). The authors interpreted the lower δ13C values as evidence for alpaca grazing on puna grasslands; however, others (e.g., Thornton et al. 2011; Szpak 2013) suggest different animal husbandry methods and question the original species differentiation. Analysis of δ15N, δ13C, and 87Sr/86Sr values from Cerro Baul and Cerro Mejía indicate that the camelids with lower δ13C values were local and fed on C3 plants, although three camelid samples with higher δ13C and δ15N values were probably foddered in the lomas (Thornton et al. 2011).

Stable isotope analysis in the Andean environment

Carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotope ratios are now well established for the reconstruction of paleodiet (DeNiro and Epstein 1978, 1981). δ13C values in terrestrial animal remains are directly related to the photosynthetic pathways of consumed plants: C3 (Calvin-Benson Cycle), C4 (Hatch-Slack Pathway), and CAM (Crassulacean Acid Metabolism) (Calvin and Benson 1948; Hatch and Slack 1966; Smith and Epstein 1971). Carbon stable isotope ratios for modern Peruvian plants demonstrate a mean δ13C value of − 13.5 ± 1.0‰ for modern wild C4 plants and − 27.6 ± 1.9‰ for modern wild C3 plants (Szpak et al. 2013). CAM plants exhibit intermediate δ13C values, but do not seem to be important in the camelid diet (San Martin and Bryant 1989; Genin et al. 1994). Both C3 and C4 plants are present in the Andean ecosystem, with C3 plants being predominant.

Among C4 taxa, maize (Zea mays) is the most significant component in the diet of the New World archeological populations (Szpak 2013). It has been assumed that significant δ13C deviation toward C4 plant range is a sign of intentional maize feeding of camelids, as a part of organized herding (Finucane et al. 2006; Thornton et al. 2011; Dufour et al. 2014). Although wild highland C4 grasses (e.g., Muhlenbergia sp.) grow in the area, it has been suggested that they would represent a small portion (15–20%) of the camelid diet (Reiner and Bryant 1986; San Martin and Bryant 1989).

According to analysis done by Szpak et al. (2013), consumable parts of modern Andean maize have a mean δ13C value of − 11.8 ± 0.4‰ and foliage mean δ13C value of − 12.9 ± 0.4‰. These results, adjusted for + 1.5‰ to account for the modern fossil fuel use, called the Suess Effect (Marino et al. 1992), give − 10.3‰ and − 11.4‰ of average δ13C values for the grains and leaves (respectively) and can be used for paleodietary reconstruction in the Andes (Szpak et al. 2013). The expected δ13C values for consumer's bone apatite and bone collagen are different, as those components are differentially affected by fractionation and derived from different macronutrient sources: the δ13C values are offset by ~ 5‰ for bone collagen and by ~ 12–14‰ for bone and tooth enamel apatite (Cerling and Harris 1999; Dufour et al. 2014; Passey et al. 2005). Therefore, bone/tooth enamel apatite is enriched in 13C relative to bone collagen by an average of + 7.6 ± 0.5‰ for herbivores (Clementz et al. 2009).

Stable nitrogen isotope values (δ15N) vary by trophic level and are used to distinguish terrestrial versus marine-based food webs (DeNiro and Epstein 1981; Schoeninger et al. 1983). δ15N values may also reflect plant fertilization (Szpak et al. 2012). Fractionation between herbivores and their food averages + 3–4‰ for δ15N (DeNiro and Epstein 1981). Plant δ15N values depend on soil characteristics, such as general water availability and/or manuring. Plants and soils in hot and arid ecosystems tend to have higher δ15N values than plants grown in cooler, more humid environments (Handley et al. 1999). Hence, camelids raised along the coast would have relatively higher δ15N values compared to those from the highlands (Thornton et al. 2011), with observed differences of 4–6‰ (Szpak et al. 2013). However, maize cultivated in the coastal irrigated fields also exhibits δ15N values comparable to highland plants (Szpak et al. 2015). In addition, lomas plants tend to exhibit relatively high δ15N values between 6 and 12‰ (Evans and Ehleringer 1994; Thornton et al. 2011), although there are no isotopic studies of lomas plant ecology. Also, two traditional fertilizers, seabird guano and camelid dung, are known to elevate δ15N values of cultivated plants by 11.3–20.0‰ or 1.8–4.2‰, respectively (Szpak et al. 2012, 2014a).

The stable oxygen isotope value (δ18O) of an organism depends on the local sources of potable water and therefore can be a useful tool to infer mobility (Knudson et al. 2012). However, the interpretation of oxygen isotope values (δ18O) in vertebrate tissues in the Andean region is less straightforward (Knudson 2009), in large part due to the marked contrasts in topography in the western Andes and the high natural variability of δ18O precipitation water (δ18Oprec). As the evaporation rate is correlated with temperature, lower δ18O values are expected in colder environments, away from the ocean shore and at higher altitudes (Dufour et al. 2014; Epstein and Mayeda 1953). Additionally, El Niño events can influence δ18O values (Knudson 2009).

Andean environmental conditions have not changed appreciably during the last 2000 years (Wells 1996; Sandweiss et al. 2007; Knudson 2009), so modern δ18Oprec values may serve as an analog. However, there are limited data for the Peruvian coast and δ18Oprec may not be comparable because mammalian body water δ18O was likely influenced by source waters consumed including riverine water or stored water, collected in cisterns (Turner et al. 2009). As no surface or groundwater values are provided, the potential for comparison is limited. To estimate the theoretical δ18Oprec value of the Huarmey River, we used the Online Isotopes in Precipitation Calculator (OPIC version 2.2, http://www.waterisotopes.org/; Bowen and Revenaugh 2003; Bowen 2016). The mean annual δ18Oprec value for Castillo de Huarmey is − 4.8‰ (annual variability − 8.7 to − 2.8‰, all expressed in mean ocean water (SMOW) standard). In addition, δ18O of water from two local wells and a spring were analyzed, with a mean value of − 10.93 ± 0.76‰ (SMOW) (Knudson et al. 2017).

Strontium and lead isotope analyses also serve as tools to reconstruct mobility, as Sr and Pb isotopic signals reflect the bedrock composition in the area where individuals lived during the formation of particular tissues (Turner et al. 2009). The geology in the study area can be divided into three major regions that run parallel to the coast. The coastal region is mainly composed of Cenozoic volcanic and plutonic rocks, expected to show generally low 87Sr/86Sr and 208Pb/204Pb, 207Pb/204Pb, 206Pb/204Pb ratios. Based on lead isotope data for ore deposits, this region was generally named Province I (Macfarlane and Petersen 1990; Kamenov et al. 2002). The region to the east of the Cenozoic igneous bedrock is mainly composed of Mesozoic sediments (lead isotope Province II), expected to show elevated Sr and Pb isotope ratios compared to the coastal region. Older sedimentary and Precambrian metamorphic rocks (lead isotope Province III) outcrop to the east of the Mesozoic sediments and are expected to show the highest Sr and the most variable Pb isotope ratios in the region. Recent work confirms this general pattern for Sr as the coastal Andean valleys show lower Sr isotope ratios, although alluvial soils accumulated along riverbanks could incorporate Sr from the adjacent highlands (Knudson and Tung 2011; Knudson et al. 2014).

Aim of the study

In this study we consider four camelid husbandry models, which could have been practiced in the Andean environment, and can be characterized by different stable isotopic signatures.

-

1.

Transhumance: herd movement between lowlands and highlands, accordingly to the agricultural calendar; presumably characterized by high fluctuations of 20nPb/204Pb, 87Sr/86Sr, and δ18O.

-

2.

Highland husbandry: animals breed only at the elevated pastures (called puna, cf. Pulgar Vidal 1987) and were occasionally brought to lowlands in trade caravans, shortly before butchery or as ready by-products. This model can be characterized by 20nPb/204Pb and 87Sr/86Sr ratios typical for highland locations, decreased δ18O values indicative of higher altitude drinking water, δ13C values expected for C3 plants, and decreased δ15N values, suggesting as probability of fertilization usage or minimal consumption of marine plants.

-

3.

Lowland husbandry: herds kept constantly at the lower altitudes and along the coast. This model would be characterized by predominantly 20nPb/204Pb and 87Sr/86Sr ratios expected for the coast, increased δ18O values which indicate an arid coastal environment, and possibly increased δ15N values caused by manuring or consumption of marine plants, and slightly increased δ13C values, caused by possible access to maize stubble.

-

4.

Enclosed husbandry: camelids kept at grass pastures in the vicinity of human settlements and probably allowed to graze the stubble of maize fields after the harvest. This model would be characterized by isotopic signatures mirroring the environment of the archeological site: local 20nPb/204Pb and 87Sr/86Sr ratios, δ18O, δ15N values consistent with local conditions, and δ13C values expected for a mixed C3–C4 plant diet.

Material

We exported 39 samples representing 34 animals from three different areas of Castillo de Huarmey (Fig. 3). Three samples came from the masonry and mudbrick platform, situated ca. 200 m to the northeast from the monumental core of the site. Archeological excavations in the 2010 and 2012 field seasons exposed an Early Horizon (800–100 bc) cemetery overlaid by a Middle Horizon rectangular mudbrick architectural compound with the faunal assemblage being part of an accumulated midden associated with the residential quarter (Fig. 4a). Sixteen samples were taken at the palatial complex, from foundation deposits with human and animal offerings dated to the Middle Horizon (Giersz 2016) which contained six complete and nine partial camelid skeletons, seemingly sacrificed (Fig. 4b). As this assemblage was poorly preserved, in order to maximize the rate of successful collagen extraction, we sampled more than one bone for several individuals (n = 4). Hence, 16 samples represent nine individuals. For CdH-3422/24m, both M2 and left M3 molars were analyzed to assess isotopic variability throughout the lifespan; this camelid was the only one with well-preserved and fully developed M2 and M3 teeth. Nineteen samples were selected from the animal offering deposits of the royal mausoleum where in 2012, Giersz and colleagues uncovered the first undisturbed Wari elite woman’s tomb (Giersz and Pardo 2014; Giersz 2016; Giersz 2017), and where camelid bones represented 98% of the faunal assemblage of the animal offerings (Fig. 4c). Lastly, one sample was taken from a camelid skeleton buried between two construction phases of the mausoleum northern wall (Fig. 4d), as a votive offering (CdH-3453).

Archeological context of the sampled camelid bones from the site of Castillo de Huarmey: a the faunal assemblage with camelid bones at the midden associated with Middle Horizon residential quarter; b one of the sacrificed camelids placed in the architectural fill of the Middle Horizon palatial complex; c the royal mausoleum with the animal offering deposits; d the votive offering of a camelid placed under the wall (© Miłosz Giersz)

Not all exported samples were suitable for analysis. In sum, 29 samples of bone (from 27 individuals) and 24 samples of enamel (from 18 individuals) were analyzed in the University of Florida’s Departments of Anthropology and Geological Sciences. Bone samples were analyzed for bone collagen (δ13C, δ15N) and bone apatite (δ13C, δ18O), while tooth samples were analyzed for tooth enamel apatite (δ13C, δ18O, 87Sr/86Sr, and 20nPb/204Pb). The majority of selected teeth were fully developed second molars (n = 20, 10 mandibular, 10 maxillary) but if poorly preserved or absent, fully developed third molars were used (n = 4, 2 mandibular, 2 maxillary).

Methods

Portions of manually cleaned bone were cut using a Dremel tool and gently crushed with a ceramic acid-cleaned mortar and pestle or a Spex 6700 freezer mill (e.g. Szpak et al. 2017).

For bone collagen, samples were demineralized using 0.1 M HCl and refreshed daily for 5–7 days. The presence of collagen pseudomorphs throughout indicated samples were completely demineralized. Samples were then rinsed with dH2O to neutral pH, and then ~ 12 ml of 0.125 M NaOH was added for 16 h to remove contaminants, such as humic and fulvic acids. Samples were then rinsed to neutral pH and ~ 10 ml 0.1 M HCl was added and all contents of the tube were transferred into 20-ml glass scintillation vials, loosely capped, and heated at 95 °C. After 5 h, 100 μl of 1.0 M HCl was added to each collagen solution to remove base-soluble organics and heated for another 5 h. Samples were removed from the oven, and each solution was placed in its respective tube, centrifuged, and the solution alone was reduced to ~2 ml at 65 °C. Samples were then frozen and freeze-dried. Each freeze-dried sample was weighed to determine percent collagen yield and then 600 μg was loaded into tin capsules and introduced to a Carlo Erba elemental analyzer connected to a Delta V isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS). δ13C was compared against the standard Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) and δ15N was compared with atmospheric nitrogen (AIR) using USG40 and USG41 standards. The precision of USGS40 (n = 6) for δ13C was ± 0.15‰ and for δ15N was ± 0.14‰.

With respect to diagenetic checks, the minimum acceptable yield of preserved collagen is 1% (van Klinken 1999) and atomic C/N should fall between 2.9 and 3.6 (DeNiro 1985). The atomic C/N ratio in bone collagen and percent collagen yield are good indicators of sample quality and possible contamination (Ambrose 1990). The percent carbon and percent nitrogen yields in uncontaminated collagen should not be lower than 13, and 4.8%, respectively (Ambrose 1990). Only measurements following all these criteria were accepted.

For bone apatite, ~ 200 mg ground powder (< 0.25 mm fraction) was loaded into 15-ml centrifuge tubes and reacted with ~12 ml 2.5% NaOCl. Once oxidation was complete (ca. 24 h), samples were rinsed to neutral pH and ~ 12 ml of 0.2 M acetic acid (C2H4O2) was added to remove secondary carbonates for 16 h, and then rinsed to neutral pH prior to being placed in freezer. Samples were then freeze-dried, weighed to estimate the carbonate yield, and 600 μg of pretreated sample was loaded into glass vials and placed into a Kiel carbonate preparation device connected to a Finnigan MAT 252 IRMS. The samples were measured against the VPDB standard using NBS-19 standards. The precision of the NBS-19 (n = 23) for δ13C was ± 0.03‰ and for δ18O was ± 0.07‰.

To monitor the quality of apatite measurements, we followed Dufour et al.’s (2014) approach by a comparison of δ13C from bone apatite to δ13C from collagen to assess the collagen loss and its affect on structural carbonate. The spacing or difference in δ13C values of bone apatite and bone collagen (Δ13Capatite-collagen) is also a useful indicator, and for herbivores is estimated at 7.6 ± 0.5‰ (Clementz et al. 2009).

Tooth enamel apatite samples were collected using a Brassler dental drill and Dedeco separating discs cutting along the highest lobe of the proximal and lingual cusps of each molar. For light isotopes, ca. 25 mg of cleaned enamel was crushed to powder using an agate mortar/pestle, weighed and placed in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube, and filled with ~ 1 ml 2.5% NaOCl for 8 h. Samples were then rinsed to neutral and ~ 1 ml of 0.2 M acetic acid was added to remove secondary carbonates. After an additional 8 h, samples were rinsed to neutral, frozen, freeze-dried, and then weighed to calculate percent yield. Like bone apatite described above, about 0.6 μg of pretreated samples was weighed and placed into a Kiel carbonate prep device connected to a Finnigan MAT 252 isotope ratio mass spectrometer for δ18O and δ13C.

To analyze strontium (Sr) and lead (Pb) isotope ratios, a 40–50 mg cleaned tooth enamel chunk was weighed and transferred to acid-cleaned Teflon vials and dissolved in 8 M HNO3 (optima) on a 120 °C hot plate. Strontium and lead were separated by ion chromatography from single aliquots as described in Valentine et al. (2008). Sr and Pb ratios were measured using a Nu-Plasma multiple-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS) and are reported relative to NBS-987 and NBS 981 standards, respectively.

To estimate the proportion of the C4 plants in the diet, we used δ13C values for 100% C3 (δ13C ≤ − 21‰, δ13C ≤ − 14‰, and δ13C ≤ − 12‰ for bone collagen, bone apatite, and enamel, respectively) and 100% C4 feeders (δ13C ≥ − 6.5‰, δ13C ≥ 0‰, and δ13C ≥ 2.5‰ for bone collagen, bone apatite, and enamel, respectively), as outlined in the graphs in Dufour et al. (2014).

To verify if camelids were local or non-local, geological samples were collected to establish a local environmental range for Sr and Pb. The local range for Sr and Pb ratios can be estimated using the environmental average values ± two standard deviations (Price et al. 2002). The Sr local range for Castillo de Huarmey was determined by Knudson et al. (2017). For Pb, we assayed two soil samples from two mortuary contexts, the mausoleum (A1) and the palatial complex (B1), and two andesite samples (RP1 and RP4) collected in the vicinity of a site. Rock and soil samples were prepared and analyzed following methods described in Valentine et al. (2015).

Statistical differences of the Castillo de Huarmey samples were evaluated using the Mann–Whitney nonparametric test, which could potentially demonstrate the possibly dimorphic character of the animal economy, even if the assumption of normal distribution(s) cannot be well justified for a small sample. Distribution of δ13C and δ15N values was tested using likelihood ratios to test for bimodality (Holzmann and Vollmer 2008) using the R package “bimodality test” (Schwaiger et al. 2013). This is a parametric test that has high statistical power and two important advantages. First, its scope is strictly limited to distinction between one population with normal distribution and two mixed populations with normal distribution, in contrast to more general tests of deviation from normal distribution, such as Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (Lilliefors 1967), or tests distinguishing between unimodal and polymodal distributions as Hartigan–Hartigan dip test (Hartigan and Hartigan 1985). Second, the likelihood ratio test allows estimation of parameters (mean and standard deviation) of two mixed populations (Holzmann and Vollmer 2008).

Results

Carbon and nitrogen isotopic measurements had good collagen yields in 21 samples; however, the mudbrick platform and the palatial complex samples’ results were not reliable (Table 1). The C/N ratio varied between 3.2 and 3.6, %N ranged between 9.2 and 16.6%, and %C ranged between 26.5 and 45.3%. Therefore, the collagen comparison within these contexts was omitted. δ15Ncol mean value was 6.84 ± 1.08‰, and δ13Ccol was − 17.09 ± 2.2‰. With respect to bone apatite, δ13Cap had a mean of − 10.05 ± 1.81‰, and the δ18Oap mean was − 1.15 ± 2.09‰ (VPDB). Δ13Cap-col ranged between 5.2 and 8.9‰ (mean 7.03 ± 1.07).

All tooth enamel samples produced δ13C and δ18O isotope data, regardless of context. If more than one sample per individual was available, average values were included for further analysis. The mean δ13Cen value was − 8.86 ± 2.23‰ and mean δ18Oen value was − 1.76 ± 2.25‰.

In total, Sr and Pb ratios were obtained for 18 and 14 individual animals, respectively (Figs. 5, 6, and 7). 87Sr/86Sr values were obtained in all analyzed enamel samples (n = 24), and 20 of the 24 enamel samples produced reliable 20nPb/204Pb values (Table 2). For four samples omitted from analysis, the Pb concentration was too low due to low voltage of 208Pb precluding reliable isotope analysis. The mean values were 87Sr/86Sr = 0.7067 ± 0.003, 208Pb/204Pb = 38.65 ± 0.05, 207Pb/204Pb = 15.63 ± 0.01, and 206Pb/204Pb = 18.78 ± 0.05. Isotope data for individuals from the palatial complex with more than one sample analyzed (n = 4) were all within error based on long-term reproducibility of the Pb, Sr, and δ18O standards reported above, and so we used the average results (m next to sample numbers in Table 1).

Analyzed environmental samples (Table 3) showed Pb ratios between 38.69 and 38.78 (208Pb/204Pb), 15.64–15.66 (207Pb/204Pb), and 18.82–18.94 (206Pb/204Pb). On the basis of analyzed environmental samples, we assume local ranges as follows: 208Pb/204Pb, 38.63–38.80; 207Pb/204Pb, 15.63–15.67; and 206Pb/204Pb, 18.74–18.97.

The average proportion of C4 plants in the camelid diet was estimated to be about 30%.

Mann–Whitney U test showed that there was a significant difference in δ13Cen between the palatial complex and mausoleum enamel samples (Z = 2.81, p < 0.005) but no significant difference in δ18Oen (Z = − 1.32, p = 0.186) (Fig. 8). δ13Cap was not tested due to the lack of appropriate results.

For all three Wari sites, the result of the test for bimodality (Table 4) in δ15Ncol values was not significant. In δ13C values, however, bimodality was observed at two sites: at Conchopata and Cerro Baul (collated together with Cerro Mejía). The difference between the two subsets is distinct, while at Castillo de Huarmey the data only slightly deviate from unimodality and this deviation is not statistically significant.

Discussion

Castillo de Huarmey camelid husbandry

The bone and tooth enamel δ13C results from Castillo de Huarmey confirm that the camelid diet included mainly C3 plants, with some contribution of C4 plants (Fig. 9). While considering the carbon spacing (Δ13Cap-col), no significant difference was observed, which suggests that there was no significant dietary change during the animals’ lifespan. A twofold foddering strategy is observed based on the samples analyzed at Castillo de Huarmey. The results from δ13Cen suggest that the camelids sacrificed in the palatial complex fed more on C3 plants than did the camelids from the mausoleum, which likely had better access to maize. We suggest that those two sacrifices were distinct events and that these animals were derived from separate herds (Fig. 8).

δ13C and δ15N distribution of camelid bone collagen from Wari sites; 95% confidence ellipses are drawn assuming bimodality of δ13C values. Estimated proportion of C4 plants in the diet after Dufour et al. (2014).

δ15N values of the Castillo de Huarmey camelids are slightly higher than those obtained from modern highland camelids (Thornton et al. 2011; Dufour et al. 2014). Such a difference is expected for camelids foddered with plants growing at lower altitudes, as δ15N values are generally higher in more arid environments. However, Castillo de Huarmey values do not suggest significant consumption of lomas plants, which would have higher δ15N values. Even the relatively high δ15N values (>8‰) observed for two Castillo de Huarmey camelids (Fig. 9) are lower than the average value (δ15N = 12.33‰) of three Cerro Baul camelids interpreted as foddering on lomas (Thornton et al. 2011). In addition, our results do not suggest extensive fertilization, although we cannot exclude the use of camelid dung or minimal amount of guano as fertilizers. Use of such fertilizers typically does not result in very high δ15N values in plant tissues and therefore is far more difficult to detect (Szpak et al. 2012).

The tooth enamel and bone apatite δ18O values suggest that the majority of animals had an 18O-enriched water source (Table 1). There is no significant difference between δ18Oen values from the mausoleum and the palatial complex. Based on the observed enamel and bone results, we calculated the δ18O of drinking water (δ18Odw) using the equation from Chenery et al. (2012). This equation is used for structural carbonate in human enamel, but there is no equation for direct calculation of δ18Odw from structural carbonate isotope values for camelids. The calculated values (Table 1) show that the camelids’ δ18Odw ranges from − 8.07 to 3.93‰. On the low end, the values overlap with the expected annual variability of the regional water (− 8.07 to − 2.8‰), based on a theoretical model by Bowen (2016). On the high end, however, the calculated δ18Odw for nine animals (half of all analyzed) are much higher than expected for regional meteoric water. Furthermore, those values are higher than modern δ18O values observed in local spring water. Given the arid environment in the area, the most likely explanation for the observed high δ18Odw is that the animals obtained water from evaporative basins. Such evaporative basins might include natural stagnant water pools or man-made reservoirs. Regardless, the observed δ18O values are not useful for the estimation of provenance for the camelids as such evaporative water basins can exist in many places in regions with an arid climate. Potentially, however, this can be interpreted as another indicator for human management, for example, if the animals were drinking water from maintained wells or reservoirs in or near the Castillo de Huarmey. Additionally, all values of δ18Odw, except the two lowest CdH-3420 δ18Odw = − 8.07‰ and CdH-3436 δ18Odw = − 8.02‰, are similar to values of camelid enamel samples from other coastal sites (Goepfert et al. 2013; Dufour et al. 2014). The two lowest δ18Odw individuals likely had distinct source of water, indicating that they were possibly raised outside the coastal region.

The Sr local range for Castillo de Huarmey, although presented in Knudson et al. (2017) as divided into separate values based on faunal and geological samples, is 87Sr/86Sr: 0.7045–0.7080. This range overlaps with other local values calculated at various Andean sites (Table 5). Among the 18 analyzed individuals, 15 exhibit 87Sr/86Sr ratios that fall within the estimated local range and three (CdH-3420, CdH-3451/52m, CdH-3436) have ratios decidedly higher than the others (Fig. 5). Interestingly, two of these individuals also show the lowest δ18Odw values (Table 1). These three outliers are also distinct from the Castillo de Huarmey human population (mean 87Sr/86Sr = 0.70738 ± 0.00030 (2σ, n = 68); Knudson et al. 2017). Furthermore, none of the coastal sites show such high 87Sr/86Sr values (Table 5). Therefore, the most likely explanation for the observed high Sr isotope ratios in these three animals is highland origin. Their presence at Castillo de Huarmey suggests strong long-distance interactions, which could be expected for the Wari Empire’s local capital (Giersz 2017). Interestingly, for two of the outliers (CdH-3420 and CdH-3436), all of the isotopic proxies suggest a different dietary base. Both have relatively low δ15N values, δ13C values that indicate predominantly C3 plants in the diet, and also δ18O values that suggest a different water source. The influence of marine-based Sr with a seawater value estimate of 87Sr/86Sr = 0.7092 (Veizer 1989) was not noticed in the samples analyzed.

In Fig. 10, the camelid 206Pb/204Pb and 208Pb/204Pb data are compared to ore Pb isotopic provinces described by Kamenov et al. (2002). The four isotopic provinces depicted are based on Pb data from ore minerals, which in turn inherit their Pb isotopic signature from local crustal rocks (Kamenov et al. 2002). In the area of Castillo de Huarmey, Provinces I, II, and III run parallel to the Pacific coast (Macfarlane et al. 1990). Province IV is located below 15°S, in southern Peru (Kamenov et al. 2002). Province I, spanning the coast is characterized by Tertiary volcanic and plutonic rocks. Province II is located to the east of Province I and the bedrock is composed of Cretaceous and older sedimentary rocks interbedded with Tertiary volcanic and plutonic rocks. Further to the east is Province III, generally characterized with older sedimentary and metamorphic bedrock than Province II.

Castillo de Huarmey camelid Pb ratios compared to Andean lead ore provinces (Kamenov et al. 2002)

As expected, the Pb isotopes of the local rocks and soils from Castillo de Huarmey (Table 3) plot within Province I (Fig. 10), as do the camelids. However, three of the Pb isotopic provinces overlap in the area where the camelid Pb data plot in Province I. In this particular case, therefore, we cannot solely use the Pb isotope data to identify if the camelids were local or non-local to the region of Castillo de Huarmey. Turner et al. (2009) combined Sr and Pb isotopic analyses to reconstruct paleomobility in the Andes, and distinguished six isotopic clusters based on tooth enamel data from Machu Picchu human remains. The camelid Sr–Pb isotope data overall fit in their cluster 3, which includes multiple regions roughly comprising two thirds of the present-day Peruvian territory. Given the multi-province overlap in Pb isotope space and the possibility that camelids originated in multiple regions based on the fit in cluster 3 of Turner et al. (2009), the most useful information in our case can be obtained from the Sr isotopes. As noted above, based on Sr isotopic signatures we can identify at least three animals that are non-local to Castillo de Huarmey. The elevated 87Sr/86Sr ratios suggest an origin to the east of the archeological site. Most likely these three camelids resided in the highlands to the east, characterized by bedrock composed of older sedimentary and/or metamorphic rocks, during the time of the formation of their enamel.

The suite of isotope data (C–N–O–Sr–Pb) reported here suggest that Castillo de Huarmey camelids were managed following enclosed husbandry. In this scenario, the camelids were kept in higher elevated grass pastures, but at relatively short distance from human settlements, and allowed to graze the stubble of maize fields after harvest. These isotopic results are similar to values obtained from camelid remains at other coastal sites (Szpak et al. 2014b, 2015), overlap with measured plant isotope values from northern Peru (Szpak et al. 2013), and corroborate Shimada and Shimada’s (1985) predictions of coastal camelid management.

Castillo de Huarmey versus other Wari sites

A comparison of δ13C and δ15N values from three Wari sites (Fig. 9; Table 4) shows broad similarities in camelid diet. The observed bimodality within Conchopata and Cerro Baul/Mejía and the relatively broad range of δ13C at Castillo de Huarmey, even if bimodality at the latter site is not statistically significant (Fig. 8), suggests two types of foddering reflecting two distinct ecological niches. One subset at each site is characterized by similar mean δ13C values, consistent with a predominantly C3-based diet with the possibility of some C4 plant consumption (likely no more than 30%, based on the estimation from Dufour et al. (2014)). The data for the three Wari sites (Table 4) clearly show that some camelids fed almost exclusively on C3 plants with no or very little maize biomass used as fodder. The second subset of δ13C is more variable, representing: a mainly C3-based diet with moderate C4 (likely maize) input at Castillo de Huarmey (only slightly differing from an exclusively C3-based diet), a higher contribution of C4 plants in diet of three camelids from Cerro Baul, and almost exclusively C4 diet at Conchopata. The intense maize foddering observed at Conchopata has not yet been explained. However, the suggested separated fodder scenario for llamas and alpacas (Finucane et al. 2006) is not confirmed, as those species could live together within one herd, and even crossbreed, causing hybrids (Shimada and Shimada 1985; Wheeler et al. 1995). Such a general bimodality has been observed in other parts of the world with environmental conditions similar to coastal Peru. In the semi-arid areas of the Middle East, for example, some limited strips of land suitable for agriculture were surrounded by dry steppes that may have been exploited only as pastures. Such a setting contributed to increased sedentism with settled farmers and city dwellers interacting with mobile tribes of herdsmen, referred to as a dimorphic society (Charles 1939; Rowton 1977; Liverani 1997). In such a dual economy, some animals (mainly pigs, cattle, but also some sheep and goats) were fed mainly with biomass of cultivated plants while others (mainly sheep and goats) spent most of the time in dry steppe pastures. Alternatively, after harvest they may have been introduced to arable fields to feed on stubble and to manure them. A similar system could have been suitable in the Andean areas where maize has been cultivated mainly in the valleys with highlands offering only meadows for camelid herding. This effect is most evident at Conchopata and much less clear at Castillo de Huarmey, which may be the consequence of lower availability of maize biomass for foddering.

As each of these sites was located in different ecological zones, the similar results could reflect one, perhaps more centrally regulated, camelid management strategy, with additional exploitation of accessible local ecological niches (e.g., Cerro Baul). The available data possibly reflect the “dimorphic” model of husbandry, which could be something between proposed model 1: transhumance and model 4: enclosed husbandry. Some herds could move between higher pastures (but not in puna), where animals spend the crop-growing phase, and the lower pastures, where they could be driven to feed on maize stubble. Simultaneously, some herds were always kept away from the agricultural lands.

Collagen data are not sufficient to check for differences in δ13C between contexts in Castillo de Huarmey, but data from tooth enamel suggest that the diet of the animals retrieved from the mausoleum included significantly more C4 plants than diet of the animals from the palatial complex. This provides additional evidence of dimorphic character of animal husbandry in the Wari cultural tradition.

Conclusions

The isotope data presented in this work show that the majority of Castillo de Huarmey camelids were local, and their diet was consistent with a coastal environment. The presence of three individuals with non-local 87Sr/86Sr ratios indicates that an inter-regional trade network existed. The δ13C distribution shows the bimodality in camelid diet in Castillo de Huarmey as well as in the other Wari sites. Some herds were foddered almost solely with C3 plants and some had greater access to C4 plants (i.e., maize). Access to the maize was restricted by perhaps short-distance transhumance, which could protect the growing crops from the damage caused by camelids. Simultaneously, herds would be kept close enough to bring them back to human settlements for grazing after the harvest or when needed for some event, e.g., for ritual sacrifice, as this scenario likely happened at Castillo de Huarmey.

References

Andrushko VA, Buzon MR, Simonetti A, Creaser RA (2009) Strontium isotope evidence for prehistoric migration at Chokepukio, valley of Cuzco. Peru Lat Am Antiq:57–75

Ambrose SH (1990) Preparation and characterization of bone and tooth collagen for isotopic analysis. J Archaeol Sci 17(4):431–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-4403(90)90007-R

Bergh SE (ed) (2012) Wari: lords of the ancient Andes. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

Bethard JD, Gaither C, Vasquez V et al (2008) Stable isotopes from Santa Rita B: subsistence and residential mobility in the Chao Valley of Peru. Invited paper presented at the 73rd Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Vancouver, BC, March 26–30

Bonavia D (2008) The south American camelids. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. University of California, Los Angeles

Bowen GJ (2016) The online isotopes in precipitation calculator, version 2.2. http://waterisotopes.org. Accessed 15 March 2016

Bowen GJ, Revenaugh J (2003) Interpolating the isotopic composition of modern meteoric precipitation. Water Resour Res 39(10). https://doi.org/10.1029/2003WR002086

Calvin M, Benson AA (1948) The path of carbon in photosynthesis. Science 107(2784):476–480. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.107.2784.476

Cerling TE, Harris JM (1999) Carbon isotope fractionation between diet and bioapatite in ungulate mammals and implications for ecological and paleoecological studies. Oecologia 120(3):347–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050868

Charles, H. (1939) Les tribus moutonnières du Moyen Euphrate. Documents d'Études Orientales, VIII. Beirut: Institut Français de Damas

Chenery CA, Pashley V, Lamb AL, Sloane HJ, Evans JA (2012) The oxygen isotope relationship between the phosphate and structural carbonate fractions of human bioapatite. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 26(3):309–319. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.5331

Clementz MT, Fox-Dobbs K, Wheatley PV, Koch PL, Doak DF (2009) Revisiting old bones: coupled carbon isotope analysis of bioapatite and collagen as an ecological and palaeoecological tool. Geol J 44(5):605–620. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.1173

Conlee CA, Buzon MR, Gutierrez AN et al (2009) Identifying foreigners versus locals in a burial population from Nasca, Peru: an investigation using strontium isotope analysis. J Archaeol Sci 36:2755–2764

DeNiro MJ (1985) Postmortem preservation and alteration of in vivo bone collagen isotope ratios in relation to palaeodietary reconstruction. Nature 317(6040):806–809. https://doi.org/10.1038/317806a0

DeNiro MJ, Epstein S (1978) Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 42(5):495–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(78)90199-0

DeNiro MJ, Epstein S (1981) Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 45(3):341–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(81)90244-1

Dufour E, Goepfert N, Gutiérrez Léon B, Chauchat C, Franco Jordán R, Sánchez SV (2014) Pastoralism in northern Peru during pre-Hispanic times: insights from the Mochica period (100–800 AD) based on stable isotopic analysis of domestic camelids. PLoS One 9(1):e87559. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087559

Epstein S, Mayeda T (1953) Variation of O18 content of waters from natural sources. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 4(5):213–224

Evans RD, Ehleringer JR (1994) Plant δ15N values along a fog gradient in the Atacama Desert, Chile. J Arid Environ 28(3):189–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-1963(05)80056-4

Finucane B, Agurto PM, Isbell WH (2006) Human and animal diet at Conchopata, Peru: stable isotope evidence for maize agriculture and animal management practices during the Middle Horizon. J Archaeol Sci 33(12):1766–1776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2006.03.012

Genin D, Villca Z, Abasto P (1994) Diet selection and utilization by llama and sheep in a high altitude-arid rangeland of Bolivia. J Range Manag 47(3):245–248. https://doi.org/10.2307/4003025

Giersz M (2017) Castillo de Huarmey. Un centro del imperio Wari en la costa norte del Perú. Ediciones del Hipocampo, Lima

Giersz M (2016) Castillo de Huarmey: centro político Wari en la costa norte del Perú. In: Giersz M, Makowski K (eds) Nuevas Perspectivas en la Organización Política Wari. ANDES. Boletín del Centro de Estudios Precolombinos de la Universidad de Varsovia. Polish Society for Latin American Studies and Institut Français d’Études Andines, Warsaw-Lima, pp. 217–262

Giersz M, Makowski K (2014) El fenómeno Wari: tras las huellas de un imperio prehispánico. In: Giersz M, Pardo C (eds) Castillo de Huarmey: el mausoleo imperial Wari, MALI, Lima, pp. 34–67

Giersz M, Pardo C (eds) (2014) Castillo de Huarmey: el mausoleo imperial Wari. Asociación Museo de Arte de Lima

Goepfert N, Dufour E, Gutiérrez B, Chauchat C (2013) Origen geográfico de camélidos en el periodo mochica (100-800 AD) y análisis isotópico secuencial del esmalte dentario: enfoque metodológico y aportes preliminares. Bull Inst Fr D'études Andin 25–48

Handley LL, Austin AT, Stewart GR et al (1999) The 15N natural abundance (δ15N) of ecosystem samples reflects measures of water availability. Funct Plant Biol 26:185–199

Hartigan JA, Hartigan PM (1985) The dip test of unimodality. Ann Stat 13(1):70–84. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176346577

Hatch MD, Slack CR (1966) Photosynthesis by sugar-cane leaves: a new carboxylation reaction and the pathway of sugar formation. Biochem J 101(1):103–111. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj1010103

Holzmann H, Vollmer S (2008) A likelihood ratio test for bimodality in two-component mixtures with application to regional income distribution in the EU. AStA Adv Stat Anal 92(1):57–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10182-008-0057-2

Horn P, Hölzl S, Rummel S et al (2009) Humans and camelids in river oases of the Ica–Palpa–Nazca region in prehispanic times–insights from HCNOS-Sr isotope signatures. In: New Technologies for Archaeology. Springer, pp 173–192

Isbell WH (2008) Wari and Tiwanaku: international identities in the central Andean Middle Horizon. In: Silverman H, Isbell WH (eds) The Handbook of South American Archaeology. Springer, New York, pp. 731–759. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-74907-5_37

Isbell WH, McEwan GF (1991) Huari administrative structure: prehistoric monumental architecture and state government. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

Kamenov G, Macfarlane AW, Riciputi L (2002) Sources of lead in the San Cristobal, Pulacayo, and Potosi mining districts, Bolivia, and a reevaluation of regional ore lead isotope provinces. Econ Geol 97:573–592

Knudson KJ (2008) Tiwanaku influence in the south central Andes: strontium isotope analysis and middle horizon migration. Lat Am Antiq:3–23

Knudson KJ (2009) Oxygen isotope analysis in a land of environmental extremes: the complexities of isotopic work in the Andes. Int J Osteoarchaeol 19(2):171–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.1042

Knudson KJ, Tung TA (2011) Investigating regional mobility in the southern hinterland of the Wari empire: biogeochemistry at the site of Beringa, Peru. Am J Phys Anthropol 145(2):299–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21494

Knudson KJ, Price TD, Buikstra JE, Blom DE (2004) The use of strontium isotope analysis to investigate Tiwanaku migration and mortuary ritual in Bolivia and Peru. Archaeometry 46(1):5–18

Knudson KJ, Williams SR, Osborn R et al (2009) The geographic origins of Nasca trophy heads using strontium, oxygen, and carbon isotope data. J Anthropol Archaeol 28:244–257

Knudson KJ, Gardella KR, Yaeger J (2012) Provisioning Inka feasts at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: the geographic origins of camelids in the Pumapunku complex. J Archaeol Sci 39(2):479–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2011.10.003

Knudson KJ, Webb E, White C, Longstaffe FJ (2014) Baseline data for Andean paleomobility research: a radiogenic strontium isotope study of modern Peruvian agricultural soils. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 6(3):205–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-013-0148-1

Knudson KJ, Giersz M, Więckowski W, Tomczyk W (2017) Reconstructing the lives of Wari elites: paleomobility and paleodiet at the archaeological site of Castillo de Huarmey, Peru. J Archaeol Sci Rep 13:249–264

Lilliefors HW (1967) On the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality with mean and variance unknown. J Am Stat Assoc 62(318):399–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1967.10482916

Liverani M (1997) “Half-nomads” on the middle Euphrates and the concept of dimorphic society. Altorient Forschungen 24:44–48

Macfarlane AW, Petersen U (1990) Pb isotopes of the Hualgayoc area, northern Peru; implications for metal provenance and genesis of a cordilleran polymetallic mining district. Econ Geol 85(7):1303–1327. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.85.7.1303

Macfarlane AW, Marcet P, LeHuray AP, Petersen U (1990) Lead isotope provinces of the Central Andes inferred from ores and crustal rocks. Econ Geol 85:1857–1880

Makowski K (2008) Andean urbanism. In: Silverman H, Isbell WH (eds) The Handbook of South American Archaeology. Springer, New York, pp. 633–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-74907-5_32

Marino BD, McElroy MB, Salawitch RJ, Spaulding WG (1992) Glacial-to-interglacial variations in the carbon isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2. Nature 357(6378):461–466. https://doi.org/10.1038/357461a0

McEwan GF, Williams PR (2012) The Wari built environment: landscape and architecture of empire. In: Bergh SE (ed) Wari: lords of the ancient Andes. Thames and Hudson, New York, pp 65–81

Miller GR, Burger RL (1995) Our father the Cayman, our dinner the llama: animal utilization at Chavin de Huantar, Peru. Am Antiq 60(03):421–458. https://doi.org/10.2307/282258

Moore KM (1989) Hunting and the origins of herding in Peru. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan

Passey BH, Robinson TF, Ayliffe LK, Cerling TE, Sponheimer M, Dearing MD, Roeder BL, Ehleringer JR (2005) Carbon isotope fractionation between diet, breath CO2, and bioapatite in different mammals. J Archaeol Sci 32(10):1459–1470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2005.03.015

Price TD, Burton JH, Bentley RA (2002) The characterization of biologically available strontium isotope ratios for the study of prehistoric migration. Archaeometry 44(1):117–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4754.00047

Pulgar Vidal J (1987) Geografía del Perú Las Ocho Regiones Naturales, 9th Edition, Peisa

Reiner RJ, Bryant FC (1986) Botanical composition and nutritional quality of alpaca diets in two Andean rangeland communities. J Range Manag 39(5):424–427. https://doi.org/10.2307/3899443

Rowton MB (1977) Dimorphic structure and the parasocial element. J East Stud 36(3):181–198. https://doi.org/10.1086/372560

Tung TA, Knudson KJ (2008) Social identities and geographical origins of Wari trophy heads from Conchopata, Peru. Curr Anthropol 49(5):915–925

San Martin F, Bryant FC (1989) Nutrition of domesticated south American llamas and alpacas. Small Rumin Res 2(3):191–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-4488(89)90001-1

Sandweiss DH, Maasch KA, Burger RL, Richardson JB, Rollins HB, Clement A (2001) Variation in Holocene El Niño frequencies: climate records and cultural consequences in ancient Peru. Geology 29(7):603–606. https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0603:VIHENO>2.0.CO;2

Sandweiss DH, Maasch KA, Andrus CFT, et al (2007) Mid-Holocene climate and culture change in coastal Peru. In: Climate change and cultural dynamics: A global perspective on Mid-Holocene transitions. Elsevier, San Diego, pp 25–50

Schoeninger MJ, DeNiro MJ, Tauber H (1983) Stable nitrogen isotope ratios of bone collagen reflect marine and terrestrial components of prehistoric human diet. Science 220(4604):1381–1383. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6344217

Schreiber KJ (1992) Wari imperialism in Middle Horizon Peru. Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Schwaiger F, Holzmann H, Vollmer S, et al (2013) Package "bimodalitytest: Testing for bimodality in a normal mixture", R package version 1.0

Shimada M, Shimada I (1985) Prehistoric llama breeding and herding on the north coast of Peru. Am Antiq 50(01):3–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/280631

Slovak NM, Paytan A, Wiegand BA (2009) Reconstructing middle horizon mobility patterns on the coast of Peru through strontium isotope analysis. J Archaeol Sci 36:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2008.08.004

Smith BN, Epstein S (1971) Two categories of 13C/12C ratios for higher plants. Plant Physiol 47(3):380–384. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.47.3.380

Szpak P (2013) Stable isotope ecology and human–animal interactions in northern Peru. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Western Ontario

Szpak P, Millaire J-F, White CD, Longstaffe FJ (2012) Influence of seabird guano and camelid dung fertilization on the nitrogen isotopic composition of field-grown maize (Zea mays). J Archaeol Sci 39(12):3721–3740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2012.06.035

Szpak P, White CD, Longstaffe FJ, Millaire JF, Vásquez Sánchez VF (2013) Carbon and nitrogen isotopic survey of northern Peruvian plants: baselines for paleodietary and paleoecological studies. PLoS One 8(1):e53763. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053763

Szpak P, Longstaffe FJ, Millaire J-F, White CD (2014a) Large variation in nitrogen isotopic composition of a fertilized legume. J Archaeol Sci 45:72–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2014.02.007

Szpak P, Millaire J-F, White CD, Longstaffe FJ (2014b) Small scale camelid husbandry on the north coast of Peru (Virú Valley): insight from stable isotope analysis. J Anthropol Archaeol 36:110–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2014.08.005

Szpak P, Chicoine D, Millaire J-F, White CD, Parry R, Longstaffe FJ (2015) Early horizon camelid management practices in the Nepeña Valley, north-central coast of Peru. Environ Archaeol 21(3):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1179/1749631415Y.0000000002

Szpak P, Metcalfe JZ, Macdonald RA (2017) Best practices for calibrating and reporting stable isotope measurements in archaeology. J Archaeol Sci Rep 13:609–616

Thornton EK, deFrance SD, Krigbaum J, Williams PR (2011) Isotopic evidence for Middle Horizon to 16th century camelid herding in the Osmore Valley, Peru. Int J Osteoarchaeol 21(5):544–567. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.1157

Tung TA (2012) Violence, ritual, and the Wari empire: a social bioarchaeology of Wari imperialism in the ancient Andes. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. https://doi.org/10.5744/florida/9780813037677.001.0001

Turner BL, Kamenov GD, Kingston JD, Armelagos GJ (2009) Insights into immigration and social class at Machu Picchu, Peru based on oxygen, strontium, and lead isotopic analysis. J Archaeol Sci 36(2):317–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2008.09.018

Valentine B, Kamenov GD, Krigbaum J (2008) Reconstructing Neolithic groups in Sarawak, Malaysia through lead and strontium isotope analysis. J Archaeol Sci 35:1463–1473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2007.10.016

Valentine B, Kamenov GD, Kenoyer JM, Shinde V, Mushrif-Tripathy V, Otarola-Castillo E, Krigbaum J (2015) Evidence for patterns of selective urban migration in the greater Indus Valley (2600–1900 BC): a lead and strontium isotope mortuary analysis. PLoS One 10(4):e0123103. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123103

van Klinken GJ (1999) Bone collagen quality indicators for palaeodietary and radiocarbon measurements. J Archaeol Sci 26(6):687–695. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1998.0385

Veizer J (1989) Strontium isotopes in seawater through time. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 17(1):141–167. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ea.17.050189.001041

Wells LE (1996) The Santa beach ridge complex: sea-level and progradational history of an open gravel coast in central Peru. J Coast Res:1–17

Wells LE, Noller JS (1999) Holocene coevolution of the physical landscape and human settlement in northern coastal Peru. Geoarchaeology 14(8):755–789. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6548(199912)14:8<755::AID-GEA5>3.0.CO;2-7

Wheeler JC, Russel AJF, Redden H (1995) Llamas and alpacas: pre-conquest breeds and post-conquest hybrids. J Archaeol Sci 22(6):833–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-4403(95)90012-8

Yacobaccio HD (2007) Andean camelid herding in the South Andes: ethnoarchaeological models for archaeozoological research. Anthropozoologica 42:143–154

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Diamond Grant (DI 2013012043) received from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Poland. The 2010–2015 field seasons of the Castillo de Huarmey Archeological Project (PIACH) were supported by grants from the National Science Center of the Republic of Poland (2970/B/H03/2009/37, NCN 2011/03/D/HS3/01609 and NCN 2014/14/M/HS3/00865), National Geographic Society (EC0637-13, GEFNE85-13, GEFNE116-14, and W335-14), and financial support from Compañia Minera Antamina S.A. We thank the Peruvian Ministry of Culture, which granted permission for the 2010–2015 field seasons of the Castillo de Huarmey Archeological Project and for the export of samples to the University of Florida (108-2015-VMPCIC-MC). Thanks are also due to T. Elliott Arnold and Ashley Sharpe for technical assistance, Kristopher Geda for final English correction, and Jason Curtis who conducted the C, N, and O isotope analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tomczyk, W., Giersz, M., Sołtysiak, A. et al. Patterns of camelid management in Wari Empire reconstructed using multiple stable isotope analysis: evidence from Castillo de Huarmey, northern coast of Peru. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11, 1307–1324 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-017-0590-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-017-0590-6