Abstract

Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) are detectable in human blood. PFAA exposure may contribute to androgen receptor (AR)-related health effects such as prostate cancer (PCa). In Norway and Sweden, exposures to PFAAs and PCa are very real concerns. In vitro studies conventionally do not investigate PFAA-induced AR disruption at human blood-based concentrations, thus limiting application to human health. We aim to determine the endocrine disrupting activity of PFAAs based upon human exposure levels, on AR transactivation and translocation. PFAAs (PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFHxS, and PFUnDA) were tested at concentrations ranging from 1/10 × to 500 × relative to human blood based upon the exposure levels observed in a Scandinavian population. Translocation was measured by high content analysis (HCA) and transactivation was measured by reporter gene assay (RGA). No agonist activity (translocation or transactivation) was detected for any PFAAs. In the presence of testosterone, AR translocation increased following exposure to PFOS 1/10 × and 100 ×, PFOA 1/10 ×, and PFNA 1 × and 500 × (P < 0.05). In the presence of testosterone, PFOS 500 × antagonised AR transactivation, whereas PFDA 500 × increased AR transactivation (P < 0.05). PFAAs may contribute to AR-related adverse health effects such as PCa. PFAAs can disrupt AR signalling via two major components: translocation and transactivation. PFAAs which disrupt one signalling component do not necessarily disrupt both. Therefore, to fully investigate the disruptive effect of human exposure-based contaminants on AR signalling, it is imperative to analyse multiple molecular components as not all compounds induce a disruptive effect at the same level of receptor signalling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are organic compounds with hydrogen atoms replaced by fluorine atoms with the exception of the functional group. Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) are a class of PFAS. Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) is a fully fluorinated anion that was intentionally produced for commercial use in electric and electronic parts, firefighting foam, and textiles. PFOS may unintentionally be produced as the degradation product of similar anthropogenic chemicals (Buck et al. 2011). PFOS and related PFAAs have been categorised as new or emerging persistent organic pollutants (POPs) due to substantial bioaccumulation and biomagnifying properties (Buck et al. 2011; Olsen et al. 2009). Consequently, PFAAs are ubiquitous and stable chemicals widely detected in humans (Buck et al. 2011; Kishi et al. 2015). Unlike classical POPs, such as dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene, PFAAs do not partition into lipid-based tissues. Instead PFAAs have affinity for blood and liver-based proteins (Sheng et al. 2016), thus potentially increasing bioavailability in many bodily tissues.

Exposure to PFAAs may contribute to adverse health effects by disrupting hormonal signalling (Vogs et al. 2019; Steenland et al. 2010; Lei et al. 2015). Exogenous substances which disrupt hormonal signalling are called endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). In Scandinavian countries such as Norway and Sweden, exposure to PFAAs is an environmental and health concern (Haug et al. 2009; Banzhaf et al. 2017). For instance, PFOS levels in Norwegian men have sharply increased since 1977 with a plateau in the mid-1990s (Haug et al. 2009). Despite this, long-chain PFAAs such as those used in the present study have high structural integrity and long elimination half-lives; therefore, human exposure is still a very relevant concern (New Jersey Drinking Water Quality Institute Health Effects Subcommittee 2015; Butt et al. 2007; Li et al. 2018; Olsen et al. 2007).

In Scandinavian countries, such as Norway and Sweden, prostate cancer (PCa) is also a major health concern as they rank sixth and seventh, respectively, in the world for age-standardised PCa risk (Bray et al. 2018). In a recent case-control study, serum concenrations of PFAAs were analysed among 201 cases with PCa and 186 population-based control subjects (Hardell et al. 2014). This study found that blood-based levels of perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA) were associated with PCa risk (Hardell et al. 2014). Additionally, PFOS, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), PFDA, perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUnDA) yielded statistically higher odds ratio in cases with first-degree relatives with PCa (Hardell et al. 2014). This study shows a clear interaction between genetic and environmental factors on the etiology of PCa; however, the authors report the suspected mechanism of action to be unknown.

PCa is an age- and endocrine-related cancer driven primarily by overstimulation of androgenic signalling (Heinlein and Chang 2004). Androgenic and anti-androgenic effects are executed molecularly by the androgen receptor (AR). The AR is a member of the nuclear receptor family that acts as a transcription factor regulating critical molecular and cellular events such as growth, proliferation, and secretion of prostate-specific antigen (PSA). The AR is activated by endogenous hormones (Guiochon-Mantel et al. 1996; Pratt et al. 1999; Black et al. 2004). Androgens such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) bind cytoplasmic AR and induce translocation to the nucleus whereby AR homodimers bind and regulate the transcriptional activity of target genes (Cutress et al. 2008). Successful receptor transactivation is dependent on receptor translocation yet in vitro-based studies tend to report on AR transactivation of a reporter plasmid transfected with a luciferase construct as their only (anti-) androgenic experimental endpoint. Functionally, the AR is involved in molecular and cellular processes beyond transactivation. Therefore, monitoring upstream translocation will reveal AR disrupting effects that may indicate more complex molecular pathways of endocrine disruption.

The aim of this study is to test human-based exposure levels of PFAAs (Berntsen et al. 2017), including PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFHxS, and PFUnDA, for a potential endocrine disrupting effect on two components of AR signalling. The first is translocation, using high content analysis (HCA), to detect agonist and antagonist effects. The second is transactivation, using reporter gene assay (RGA), to also detect agonist and antagonist effects. Combining both assays will allow for the detection of a new mechanism of action by which human-based exposure levels of PFAAs induce a disruptive effect on AR signalling, as reporting solely based upon one component of AR signalling may lead to potentially harmful PFAAs being categorised as having no endocrine disrupting activity. This will serve as a valuable screening process to detect for endocrine disruptors which mediate AR-related disruption via gene transactivation or via an alternative biological pathway linked to translocation.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

All reagents were purchased from Life Technologies (Paisley, UK) unless otherwise stated. Testosterone, phosphate buffered saline (PBS), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and MTT powder were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, Dorset, UK). Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) except for PFHxS which was purchased from Santa Cruz (Dallas, USA). The luciferase reporter gene assay kit was purchased from Promega (Southampton, UK). Hoechst 33342 was purchased from Thermo Scientific (UK).

Perfluoroalkyl Acids

PFAAs were based on concentrations measured in human blood, according to recent studies of the Scandinavian population (Berntsen et al. 2017), as shown in Table 2. All PFAAs (PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFHxS, and PFUnDA) were tested at 1/10 ×, 1 ×, 50 ×, 100 ×, and 500 × relative to blood-based concentrations levels, using stably transfected AR cell lines TARM-Luc (RGA) and recombinant AR U-2 OS (HCA).

Cell Culture

All cells were routinely cultured in 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

TARM-Luc Cells

TARM-Luc cells were obtained from the University of Liege (Dr Marc Muller) and previously generated by Willemsen and colleagues (Willemsen et al. 2004). TARM-Luc cells are androgen-sensitive cells with a pSV-AR0 expression vector which express a luciferase reporter protein in response to androgens. TARM-Luc cells were cultured in DMEM Glutamax™ supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS). For seeding and exposures, TARM-Luc cells were cultured in DMEM Glutamax™ supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped (CCS)-FBS.

Recombinant AR U-2 OS Cells

Recombinant U-2 OS cells with an AR (GenBank Acc. NM_000044) coding sequence (AR U-2 OS) fused to the C-terminus of an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) stably integrated onto the human osteosarcoma U-2 OS line (ATCC® HTB-96™) were cultured in DMEM Glutamax™ supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin (P/S), 2 mM l-Glutamine, and 0.5 mg/ml G418 sulphate. For experiments, cells were seeded in DMEM Glutamax™ supplemented with 10% CCS-FBS, 1% P/S, 2 mM l-Glutamine, and 0.5 mg/ml G418 sulphate. For exposures, cells were cultured in DMEM Glutamax™ supplemented with 1% P/S and 2 mM l -Glutamine.

Reporter Gene Assay

The AR reporter gene assay was performed as previously described (Frizzell et al. 2011). Briefly, TARM-Luc cells were seeded 40,000 cells per well in specialised white-walled, clear flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Greiner, Bio-One, Frickenhausen, Germany). Plates were incubated at 37 °C 5% CO2 overnight. Subsequently, cells were exposed to PFAAs in the presence of the solvent control (SC) DMSO (0.2% v:v in media) at 1/10 ×, 1 ×, 50 ×, 100 ×, and 500 × relative to blood level for the agonist test. For the antagonist test, the positive control (PC) testosterone was used at 50 nM and each PFAA was combined with the PC at 1/10 ×, 1 ×, 50 ×, 100 ×, and 500 × relative to blood level. Exposure of cells lasted 48 h. Cells were lysed with 1 × cell lysis reagent facilitated by agitation. Plates were then read using a Mithras Multimode Reader (Berthold, Other, Germany) which injected each well with 100 µl of luciferase (made according to manufacturer’s protocol; consisting of luciferase assay buffer and luciferase assay substrate) and measured the response of each well via detection of luminescence. TARM-Luc cells upon AR transactivation expressed a luciferase signalling protein allowing for the detection of both agonist and antagonist responses which were compared to the SC and PC, respectively.

High Content Analysis

Recombinant AR U-2 OS cells were seeded 6,000 cells per well in black-walled 96-well plates with clear flat bottoms (Greiner, Germany). Plates were incubated at 37 °C 5% CO2 overnight. Subsequently, cells were exposed as described above in "Reporter Gene Assay" section reporter gene assay. After 6 h of exposure, cells were washed with 1 × PBS and fixed using 5% formalin. Cells were then washed twice with 1 × PBS and subsequently stained using 2 µM Hoechst 33342. Plates were read using CellInsight NXT High Content Analysis Platform (ThermoFisher Scientific, UK) using Spot Detector Bioapplication which measures the translocation activity of the AR allowing for the detection of agonist and antagonist responses which were compared to the SC and PC, respectively.

Recombinant AR U-2 OS cells express a stably transfected AR fused with an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP-AR). A wavelength of 485 nm was used to detect EGFP-AR localisation upon successful AR binding to androgen response elements (AREs). This is illustrated in Fig. 1. The channel 2 experimental endpoint measuring successful receptor translocation was spot count per object:

Illustration of the AR translocation event. In unstimulated (or solvent control) recombinant AR U-2 OS cells, enhanced green fluorescent protein androgen receptor (EGFP-AR) is localised to the cytoplasm of the cells. Upon exposure to androgens such as testosterone, the EGFP-AR translocates to the cell nucleus whereby it binds to AREs in the promoter region of target genes. The HCA platform measures the formation of nuclear foci. For an agonist response, there is an increase in nuclear foci. Upon exposure to anti-androgens such as enzalutamide, EGFP-AR can still translocate to the nucleus; however, it is prevented from binding to AREs. For an antagonist response, there is a reduction in nuclear foci compared to the positive control. The ThermoFisher HCA platform refers to the formation of nuclear foci as “spots” and is measured using the Spot Detector bioapplication

Hoechst 33342 was used to counter stain cell nuclei in each well. A wavelength of 386 nm was used to detect binding of Hoechst 33342 to nuclei. Output parameters included object count (cell number), nuclear area, and nuclear intensity.

MTT Assay

TARM-Luc and recombinant AR U-2 OS cells were seeded in clear flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and followed the same seeding and exposure protocol as described. After 48 h (TARM-Luc) or 6 h (recombinant AR U-2 OS) of exposure, cells were incubated with MTT (0.33 mg/ml) solution. Healthy cells convert soluble yellow MTT solution to insoluble purple formazan crystals. Formazan crystals were solubilised in DMSO facilitated by agitation at 37 °C. Optical density was measured, as previously described (Shannon et al. 2019), using a Sunrise spectrophotometer at 570 nm with a reference filter at 630 nm (TECAN, Switzerland). Metabolic activity was calculated as a percentage absorbance of the sample compared with the absorbance of the SC. Metabolic activity was used as an indirect measure of gross cellular health.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicate and in three independent exposures. Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel in addition to Graphpad PRISM software, version 5.01 (San Diego, CA). Values are expressed as the mean of 9 triplicates from the 3 independent exposures ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Data are expressed as a percentage of the solvent or positive controls, where applicable. Analysis carried out includes (i) one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's procedure for multiple comparisons; the mean concentrations were tested for significant difference at the 95% confidence level. Significant values were as follows: P ≤ 0.05 (*), P ≤ 0.01 (**), and P ≤ 0.001 (***).

Results

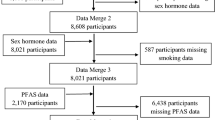

Endocrine disrupting activity of 6 PFAAs relevant to human exposure levels on AR transactivation and translocation was investigated. Concentrations of PFAAs were based upon the exposure levels detected in Scandinavian blood (Berntsen et al. 2017).

Cytotoxicity and Cellular Health

Gross cytotoxicity was evaluated in the AR RGA (TARM-Luc) and AR HCA (recombinant AR U-2 OS) cell models by quantifying metabolic activity using MTT conversion (Figs. 2 and 3, respectively). In AR RGA (TARM-Luc) cells, PFOS 1/10 × and 50 ×, PFOA 1 ×, and PFNA 1 × decreased metabolic by 13.9% ± 3.4 SEM, 13.3% ± 5 SEM, 15.5% ± 4.1 SEM, and 19.6% ± 4.1 SEM, respectively (Fig. 2a–c). Conversely, PFHxS 500 × and PFUnDA 100 × increased metabolic activity by 11.8% ± 4.7 SEM and 13% ± 3.1 SEM, respectively (Fig. 2e, f). For HCA (AR U-2 OS) cells, PFOS 500 × increased metabolic activity by 9.7% ± 3.2 SEM (Fig. 3a). Additionally, cellular health in the AR translocation assay (recombinant AR U-2 OS) was monitored using a HCA platform. Here, multiple parameters for pre-lethal cytotoxicity for nuclear morphology (nuclear area, nuclear intensity) were measured, in addition to gross cytotoxicity (cell number). PFOS, PFNA, and PFDA, all at 500 × blood level, deceased cell number by 23.2% ± 3.7 SEM, 21.5 ± 3.6 SEM, and 22.2% ± 5.1 SEM, respectively (Fig. 4a). Minor changes in nuclear area (Fig. 4b) and nuclear intensity (Table 2) were observed across most samples. A full summary of the cytotoxicity and cellular health results is shown in Table 1.

Metabolic effect of 6-h PFAA exposure in the recombinant AR U-2 OS cell line. Metabolic activity, as determined by MTT, of recombinant AR U-2 OS cells following 6-h exposure to PFAAs. Results are representative of three independent exposures (n = 3, mean ± SEM). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Exposure time = 6 h

Pre-lethal cytotoxicity markers following 6-h exposure to PFAAs in the recombinant AR U-2 OS cell line. a Changes in object count in response to PFAAs compared to SC. b Changes in nuclear area in response to PFAAs compared to SC. Changes for the nuclear intensity parameter can be found in Table 2. Results are representative of three independent exposures (n = 3, mean ± SEM). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Only significant results are presented for nuclear intensity parameter

Androgen Receptor (AR) mediated Reporter Gene Transactivation

At the concentrations tested (1/10 ×, 1 ×, 50 ×, 100 ×, and 500 ×), none of the PFAAs tested showed any agonist activity on AR transactivation when compared to the SC. When screened for antagonism, in the presence of testosterone, PFOS 500 × antagonised AR transactivation by 19.7% ± 5.4 SEM compared to the PC (P < 0.05, Fig. 5). In contrast, PFDA 500 × increased AR transactivation by 26.6% ± 11.5 SEM compared to the PC alone (P < 0.05, Fig. 5). A summary of the observed effect on AR transactivation can be seen in Table 2.

Transactivation effects of 48-h exposure to PFAAs on the androgen receptor in the TARM-Luc cell line. Analysing transactivation of the AR following PFAA exposure. Results are representative of three independent exposures (n = 3, mean ± SEM). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Only significant results are presented

Translocation of the Androgen Receptor in the Recombinant AR U-2 OS Model

At the concentrations tested (1/10 ×, 1 ×, 50 ×, 100 ×, and 500 ×), none of the PFAAs tested showed any agonist activity on AR translocation when compared to the SC (Fig. 6 and Table 2). However, when tested in the presence of testosterone, PFOS 1/10 ×, 100 ×, and 500 ×, PFOA 1/10 ×, and PFNA 1 × and 500 × significantly increased AR translocation activity by 28.5% ± 9.1 SEM, 27.9% ± 9.2 SEM, 41.2% ± 10.1 SEM, 30.4% ± 12 SEM, 26.4% ± 9 SEM, and 42% ± 6.9 SEM, respectively, compared to the PC alone (P < 0.05, Fig. 6). Images from the translocation assay (for SC, PC, PC + PFOS 1/10 × and 100 ×, PFOA 1/10 ×, and PFNA 1 × only) are shown in Fig. 6. The remaining PFAAs, PFDA, PFHxS, and PFUnDA, did not significantly change AR translocation activity compared to the PC (Table 2). A summary of the observed effect on AR transactivation can be seen in Table 2.

Translocation effects of 6-h exposure to PFAAs on the androgen receptor in recombinant AR U-2 OS cell line. a Analysing AR translocation activity following exposure to PFAAs + PC compared to the PC alone. Figure includes representative images of the antagonist test; upper panels = channel 1 (nucleus), middle panels = channel 2 (EGFP-AR localisation), and lower panels = composite (channel 1 + channel 2). Results are representative of three independent exposures (n = 3, mean ± SEM). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Only significant results are presented. × 10 objective magnification. Scale bars = 100 µm

Discussion

Human exposure-based PFAAs were evaluated for their potential endocrine disruptive effect on AR signalling using in vitro cell models. Two major components of AR signalling were assayed; transactivation (by RGA) and translocation (by HCA). Additionally, assays indicative of cellular health were carried out concomitantly with each assay to control for sample cytotoxicity. Cytotoxicity and cellular health are important to consider for cell-based assays as the experimental endpoints may be impacted by sample-induced cytotoxicity (Mamsen et al. 2017; Eke et al. 2017). Two cytotoxicity assays were utilised as assay controls: MTT assay and HCA.

In a similar study, PFOS and PFDA were found to be cytotoxic at ≥ 1 × 10–4 molar or 1000 µM as determined by MTT (Kjeldsen and Bonefeld-Jorgensen 2013). Presently, however, the upper limit concentration of PFOS and PFDA was 2.1 µM and 0.02 µM, respectively. This illustrates the need for human-based exposure levels to be used in vitro if conclusions regarding human health are to be made. In the present study, PFAA concentrations are based upon blood-based levels measured in a Scandinavian population (Berntsen et al. 2017) as shown in Table 2, and thus have more relevant implications for human health.

Cytotoxicity results highlight limitations of the MTT assay used to determine sample-induced cytotoxicity. In the same experimental setting, recombinant AR U-2 OS cells following exposure to PFOS 500 × increased metabolic activity as determined by MTT; however, cell number decreased as measured by HCA. Thus, two markers of gross cellular health directly contradict one another. The MTT assay is dependent on the oxidoreductase enzyme succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), located in the inner mitochondrial membrane, to catalyse the reduction of the tetrazolium dye MTT to insoluble formazan (Chacon et al. 1997; Roomi et al. 2016). Therefore, it would be more appropriate to implicate changes in MTT as changes in metabolic activity. Additional limitations of the MTT assay include bioavailability of experimental compounds with fluctuations in cell seeding density (Riss et al. 2004), MTT-induced toxicity (Lu et al. 2012), and MTT incubation time (Riss et al. 2004). Given the limitations of the MTT assay, future investigations which directly measure gross cellular toxicity should be used.

When investigating potential EDCs, transactivation-based assays such as reporter gene assays are commonly used to determine endocrine disrupting effects (Kjeldsen and Bonefeld-Jorgensen 2013; Frizzell et al. 2011). Only using transactivation-based assays to investigate AR-mediated endocrine disruption limits the magnitude of endocrine disruption an EDC may induce. This is the case for PFOS 1/10 × and 100 ×, PFOA 1/10 ×, and PFNA 1 × as each of these PFAAs increased AR translocation yet did not show any effect in terms of AR transactivation. Therefore, making conclusions based solely upon one aspect of receptor signalling may lead to false-negative results as compounds may induce an endocrine disrupting effect via different molecular mechanisms. Further investigation to determine the effect of PFAA-induced AR translocation in the nucleus would potentially elucidate the full extent by which AR signalling is disrupted. Molecular biology techniques such as chromatin-immunoprecipitation combined with sequencing followed by transcriptional analysis would determine the epigenetic changes induced by PFAAs and the effect on subsequent transcription of AR target genes responsible for cell growth and proliferation, thus providing an in-depth analysis of the mechanism of action by which PFAAs disrupt AR signalling.

Recent work by Kjeldsen and Bonefeld-Jorgensen (2013) demonstrated that PFOS at 50 µM and PFDA at 100 µM antagonised AR transactivation. Despite concentrations of PFOS between the two studies being vastly different (Table 2), an antagonistic effect was seen in both studies suggesting that once the antagonistic effect is achieved (500 ×) it is maintained at higher concentrations (50 µM) and is not limited to the cell model used to express the AR-luciferase reporter construct. The conflicting PFDA result may be explained by the fact that PFDA was used at 0.02 µM in the current study, a 5000-fold reduction in the concentration used in the Kjeldsen and Bonefeld-Jorgensen (2013) study.

A possible reason for the contrasting PFDA result may be explained by a biphasic effect. The PCa cell line LNCaP is androgen-dependent for growth and proliferation in vitro (Schuurmans et al. 1988; Sonnenschein et al. 1989; Bélanger et al. 1990). DHT exposure from 10–12 M to 10–10 M positively increases cell growth by AR-mediated signalling until a shutoff point > 3 × 10–10 M. At this point cell growth ceases and regresses. In another study, LNCaP cells exhibited a clear biphasic bell-shaped dose response curve for DHT exposure (Lee et al. 1995). Stipulating cell proliferation and growth is positively correlated with AR transactivation; this may explain the contrasting results in the current study and the study by Kjeldsen and Bonefeld-Jorgensen (2013). An illustration of this is shown in Fig. 7. Despite difference in methodology and experimental design between each of the studies, the core biological dependency is the same as all cells are dependent AR signalling and the experimental outcome is AR transactivation. Current results therefore reiterate the importance of exposure concentration levels in vitro, and given our exposure concentration is based upon actual human blood data, our results are much more relevant to human exposure and health. Furthermore, disruption of AR signalling may cause AR-mediated health effects such as PCa (Mamsen et al. 2017; Eke et al. 2017). In Swedish men, blood-based levels of PFAAs were positively correlated with PCa risk and increased AR transactivation. Therefore, it is possible PFAAs are involved in the pathogenesis of PCa by contributing to the overstimulation of androgenic signalling via the AR, and our study is the first to demonstrate this at human-based exposure levels in vitro.

Illustration of possible AR transactivation effects observed in the current study vs a recent study. Bell curve is based upon results reported in LNCaP cells following DHT exposure (Lee et al. 1995). Comparison between recent study (Kjeldsen and Bonefeld-Jorgensen 2013) and the current study which may explain the biphasic effects on AR transactivation associated with PFDA exposure. PC positive control (50 nM testosterone), DHT dihydrotestosterone

Conclusion

PFAA concentrations based upon the exposure profile of the human Scandinavian population disrupt AR signalling by two different biological mechanisms. The first is mediated by increasing receptor translocation (PFOS 1/10 × and 100 ×, PFOA 1/10 ×, and PFNA 1 ×) leading to an increased presence of AR in the nucleus. The second is by disrupting AR transactivation (PFOS 500 × and PFDA 500 ×). PFAA exposure and PCa are health concerns in Scandinavian countries such as Norway and Sweden. Exposure to such PFAAs may contribute to AR-mediated adverse health effects such as PCa by disrupting AR signalling. Further investigation into the mechanism by which PFAAs increase AR translocation is needed, in addition to the epigenetic, transcriptional, and proteomic profiling of increased PFAA-induced nuclear AR, to fully address the endocrine disrupting effect and possible etiology for AR-related health effects such as PCa. Additionally, PFAAs at specified concentrations which disrupted AR transactivation were not the same as those which disrupted AR translocation, thus addressing the necessity of using more than one method to evaluate endocrine disrupting potential of PFAAs and the wider category of POPs.

Change history

09 September 2019

The current title reads: Human-Based Exposure Levels of Perfluoroalkyl Acids May Induce Harmful Effects to Health by Disrupting Major Components Androgen Receptor Signalling In Vitro. However the correct title should be: Human-Based Exposure Levels of Perfluoroalkyl Acids May Induce Harmful Effects to Health by Disrupting Major Components of Androgen Receptor Signalling In Vitro. As seen, there is an ���of��� missing in the title between words ���component��� and ���androgen���.

References

Banzhaf S, Filipovic M, Lewis J et al (2017) A review of contamination of surface-, ground-, and drinking water in Sweden by perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). Ambio 46:335–346

Bélanger C, Veilleux R, Labrie F (1990) Stimulatory effects of androgens, estrogens, progestins, and dexamethasone on the growth of the LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci 595:399–402

Berntsen HF, Berg V, Thomsen C et al (2017) The design of an environmentally relevant mixture of persistent organic pollutants for use in in vivo and in vitro studies. J Toxicol Environ Health A 80:1–15

Black BE, Vitto MJ, Gioeli D et al (2004) Transient, ligand-dependent arrest of the androgen receptor in subnuclear foci alters phosphorylation and coactivator interactions. Mol Endocrinol 18:834–850

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I et al (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68:394–424

Buck RC, Franklin J, Berger U et al (2011) Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr Environ Assess Manag 7:513–541

Butt CM, Muir DC, Stirling I et al (2007) Rapid response of Arctic ringed seals to changes in perfluoroalkyl production. Environ Sci Technol 41:42–49

Chacon E, Acosta D, Lemasters JJ (1997) Primary cultures of cardiac myocytes as in vitro models for pharmacological and toxicological assessments. In: In vitro methods in pharmaceutical research, chap 9. The University Press, Cambridge, pp 209–223

Cutress ML, Whitaker HC, Mills IG et al (2008) Structural basis for the nuclear import of the human androgen receptor. J Cell Sci 121:957–968

Eke D, Celik A, Yilmaz MB et al (2017) Apoptotic gene expression profiles and DNA damage levels in rat liver treated with perfluorooctane sulfonate and protective role of curcumin. Int J Biol Macromol 104:515–520

Frizzell C, Ndossi D, Verhaegen S et al (2011) Endocrine disrupting effects of zearalenone, alpha- and beta-zearalenol at the level of nuclear receptor binding and steroidogenesis. Toxicol Lett 206:210–217

Guiochon-Mantel A, Delabre K, Lescop P et al (1996) The Ernst Schering poster award. Intracellular traffic of steroid hormone receptors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 56:3–9

Hardell E, Karrman A, van Bavel B et al (2014) Case-control study on perfluorinated alkyl acids (PFAAs) and the risk of prostate cancer. Environ Int 63:35–39

Haug LS, Thomsen C, Becher G (2009) Time trends and the influence of age and gender on serum concentrations of perfluorinated compounds in archived human samples. Environ Sci Technol 43:2131–2136

Heinlein CA, Chang C (2004) Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr Rev 25:276–308

Kishi R, Nakajima T, Goudarzi H et al (2015) The association of prenatal exposure to perfluorinated chemicals with maternal essential and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids during pregnancy and the birth weight of their offspring: the Hokkaido study. Environ Health Perspect 123:1038–1045

Kjeldsen LS, Bonefeld-Jorgensen EC (2013) Perfluorinated compounds affect the function of sex hormone receptors. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 20:8031–8044

Lee C, Sutkowski DM, Sensibar JA et al (1995) Regulation of proliferation and production of prostate-specific antigen in androgen-sensitive prostatic cancer cells, LNCaP, by dihydrotestosterone. Endocrinology 136:796–803

Lei M, Zhang L, Lei J et al (2015) Overview of emerging contaminants and associated human health effects. Biomed Res Int 2015:404796

Li Y, Fletcher T, Mucs D et al (2018) Half-lives of PFOS, PFHxS and PFOA after end of exposure to contaminated drinking water. Occup Environ Med 75:46–51

Lu L, Zhang L, Wai MS et al (2012) Exocytosis of MTT formazan could exacerbate cell injury. Toxicol In Vitro 26:636–644

Mamsen LS, Jonsson BAG, Lindh CH et al (2017) Concentration of perfluorinated compounds and cotinine in human foetal organs, placenta, and maternal plasma. Sci Total Environ 596–597:97–105

New Jersey Drinking Water Quality Institute Health Effects Subcommittee (2015) Health-based maximum contaminant level support document: perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA). New Jersey Drinking Water Quality Institute Health Effects Subcommittee

Olsen GW, Burris JM, Ehresman DJ et al (2007) Half-life of serum elimination of perfluorooctanesulfonate, perfluorohexanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanoate in retired fluorochemical production workers. Environ Health Perspect 115:1298–1305

Olsen GW, Chang SC, Noker PE et al (2009) A comparison of the pharmacokinetics of perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS) in rats, monkeys, and humans. Toxicology 256:65–74

Pratt WB, Silverstein AM, Galigniana MD (1999) A model for the cytoplasmic trafficking of signalling proteins involving the hsp90-Binding immunophilins and p50cdc37. Cell Signal 11:839–851

Riss TL, Moravec RA, Niles AL, Duellman S, Benink HA, Worzella TJ, Minor L (2004) Cell viability assays. In: Sittampalam GS, Coussens NS, Brimacombe K (eds) Assay guidance manual. Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda.

Riss TL, Moravec RA (2004) Use of multiple assay endpoints to investigate the effects of incubation time, dose of toxin, and plating density in cell-based cytotoxicity assays. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2:51–62

Roomi MW, Kalinovsky, Rathet al (2016) Chapter 11—nutraceuticals in cancer prevention, pp 135–144.

Schuurmans AL, Bolt J, Mulder E (1988) Androgens stimulate both growth rate and epidermal growth factor receptor activity of the human prostate tumor cell LNCaP. Prostate 12:55–63

Shannon M, Wilson J, Xie Y et al (2019) In vitro bioassay investigations of suspected obesogen monosodium glutamate at the level of nuclear receptor binding and steroidogenesis. Toxicol Lett 301:11–16

Sheng N, Li J, Liu H et al (2016) Interaction of perfluoroalkyl acids with human liver fatty acid-binding protein. Arch Toxicol 90:217–227

Sonnenschein C, Olea N, Pasanen ME et al (1989) Negative controls of cell proliferation: human prostate cancer cells and androgens. Cancer Res 49:3474–3481

Steenland K, Fletcher T, Savitz DA (2010) Epidemiologic evidence on the health effects of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). Environ Health Perspect 118:1100–1108

Vogs C, Johanson G, Naslund M et al (2019) Toxicokinetics of perfluorinated alkyl acids influences their toxic potency in the Zebrafish embryo (Danio rerio). Environ Sci Technol 53:3898–3907

Willemsen P, Scippo ML, Kausel G et al (2004) Use of reporter cell lines for detection of endocrine-disrupter activity. Anal Bioanal Chem 378:655–663

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 722634. We also gratefully acknowledge PhD Studentship funding provided by the Department for Education (DfE) Northern Ireland, and allocated by Queen’s University Belfast as a supportive studentship for the PROTECTED ITN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

McComb, J., Mills, I.G., Berntsen, H.F. et al. Human-Based Exposure Levels of Perfluoroalkyl Acids May Induce Harmful Effects to Health by Disrupting Major Components of Androgen Receptor Signalling In Vitro. Expo Health 12, 527–538 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12403-019-00318-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12403-019-00318-8