Abstract

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the classic progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease (ILD), but some patients with ILDs other than IPF also develop a progressive fibrosing phenotype (PF-ILD). Information on use and cost of healthcare resources in patients with PF-ILD is limited.

Methods

We used USA-based medical insurance claims (2014–2016) to assess use and cost of healthcare resources in PF-ILD. Patients with at least two ILD claims and at least one pulmonologist visit were considered to have ILD. Pulmonologist visit frequency was used as a proxy to identify PF-ILD (at least four visits in 2016, or at least three more visits in 2016 vs. 2014).

Results

Of 2517 patients with non-IPF ILD, 15% (n = 373) had PF-ILD. Mean annual medical costs associated with ILD claims were $35,364 in patients with non-IPF PF-ILD versus $20,211 in the non-IPF ILD population. In 2016, patients with non-IPF PF-ILD made more hospital ILD claims than patients with non-IPF ILD (10.5 vs. 4.7).

Conclusions

These findings suggest higher disease severity and overall healthcare use for patients with a non-IPF ILD manifesting a progressive fibrosing phenotype (non-IPF PF-ILD).

Plain Language Summary

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a group of similar lung conditions with lung fibrosis, scarring, or inflammation of the lung tissue. Some patients with ILD also have worsening lung fibrosis, referred to as “progressive fibrosis” (PF-ILD). The most common type of PF-ILD is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), which has no known cause. Although much is known about IPF, there is limited information available on how often patients with ILDs other than IPF (non-IPF ILD) use healthcare, or the costs associated with the disease. This study used US medical insurance claims to gain further insights. The study examined data from over 2500 patients with non-IPF ILD, of which 15% had PF-ILD. Patients defined as having PF-ILD had higher yearly medical costs and used healthcare services more often than other patients with ILD. This study highlights the economic burden of non-IPF ILD with progressive fibrosis (non-IPF PF-ILD).

Similar content being viewed by others

Why carry out this study? |

There is a group of patients with non-IPF ILD that develop a progressive fibrosing phenotype (PF-ILD). |

PF-ILD is associated with worsening respiratory symptoms, lung function, and early mortality. |

What was learned from the study? |

Claims analysis shows that patients with PF-ILD have higher healthcare utilization and related costs. |

Medical costs for patients with PF-ILD also appear to increase over time. |

Higher costs and healthcare utilization in PF-ILD are suggestive of more severe disease with a greater need for medical care. |

Introduction

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) encompasses a group of more than 200 distinct lung disorders sharing a similar clinical, physiologic, radiologic, and pathologic presentation despite their diverse underlying etiologies [1, 2]. Clinical data indicate that a subset of ILDs exhibit a progressively fibrosing phenotype termed “progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease” (PF-ILD) [3, 4]. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the archetypal PF-ILD with an incidence of 3–9 cases per 100,000 in Europe and the USA (2000–2012). Incidence of IPF is likely to increase worldwide as disease awareness and diagnostics improve [5, 6]. Prior to the availability of antifibrotic therapy for the treatment of IPF, mean survival after an IPF diagnosis was estimated to be 3–5 years [6, 7]. Some patients with chronic fibrosing ILDs other than IPF also develop a progressive phenotype (non-IPF PF-ILD; hereafter, “PF-ILD”), typified by worsening respiratory symptoms, lung function, and early mortality [4, 8,9,10,11]. Currently, immunosuppressants are used to treat patients with non-IPF ILD; however, there remains a high unmet need for effective and tolerable treatments for patients with fibrosing ILDs that exhibit disease progression despite treatment [4, 12].

Limited data exist on incidence, prevalence, disease course, and mortality rate across different forms of ILD. Furthermore, clinical evidence guiding optimal management, healthcare utilization, and their associated costs is sparse. This study aimed to facilitate understanding about healthcare resources utilization and costs associated with PF-ILD in the USA.

Methods

US-based medical insurance claims and Electronic Health Record data from patients who had at least one medical claim (for any condition) in each of 2014, 2015, and 2016 were analyzed. Patients were considered to have ILD if they had at least two claims with an ILD diagnosis (based on ILD International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-9/10 codes [Tables S1A and 1B in the supplementary material]) and at least one pulmonologist visit between 2014 and 2016. To stabilize the dataset (as patients could enter or leave at any time), patients were required to have at least one ILD claim per year and at least two medical claims in both halves of each year. Patients with an IPF diagnosis were excluded from the analysis. Only data from patients with an ILD other than IPF (non-IPF ILD) were analyzed in this study.

Since clinically meaningful data are not collected in the ICD codes (e.g., imaging, pulmonary function testing), pulmonologist visit frequency was considered an appropriate proxy to identify patients with PF-ILD. This was based on the following evidence: (i) physician interviews, indicating that patients are more likely to visit their pulmonologist with increasing frequency if their ILD is progressing, and (ii) real-world data analysis that showed a correlation between increased frequency of pulmonologist visits and increases in other utilization metrics indicative of severe/worsening disease (inpatient, outpatient, and emergency room [ER] visit frequency). Patients with PF-ILD were defined as the subset of patients with non-IPF ILD with at least four pulmonologist visits in 2016 (indicative of severe disease) or at least three more pulmonologist visits in 2016 than in 2014 (indicative of worsening disease).

Analysis of healthcare resource utilization and costs was limited to patients identified as having non-IPF ILD and the subpopulation of patients with PF-ILD. Medical costs consisted of costs associated with claims (either ILD-specific claims, or all medical claims) from physician offices, ERs, hospitals, and other healthcare places of service. The analyses reported here were based on US-based medical insurance claims and Electronic Health Record data, and do not contain data from any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Permissions to access the database were obtained from the data provider (Decision Resources Group).

Results

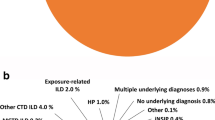

Overall, 113,752 patients were identified as having ILD. In this group, 2517 patients (2.2%) had at least one ILD claim per year, at least two medical claims in both halves of each year, and a non-IPF ILD diagnosis. Categorizing patients by pulmonologist visit frequency identified 373 patients (15%) within this group as having non-IPF PF-ILD.

Over the 3-year period, mean annual medical costs per patient were higher for PF-ILD than ILD: $77,666 versus $68,085 for any medical claims, and $35,364 versus $20,211 for ILD-specific claims. Mean annual medical costs associated with any claims increased between 2014 and 2016 in both PF-ILD and ILD groups, but to a much greater degree in the PF-ILD group (+ $23,776 vs. + $5190 for PF-ILD and ILD, respectively). For ILD-specific claims, the change in mean annual medical costs between 2014 and 2016 was much smaller (+ $1501 vs. − $956 for PF-ILD and ILD, respectively). Notably, the mean annual medical costs of ILD-specific claims per patient with PF-ILD in 2016 was 87% higher relative to the ILD group ($37,555 vs. $20,030 per patient). Median costs followed the same trend (Table S2 in the supplementary material).

Patients with PF-ILD had higher utilization across all healthcare settings (physician’s office, ER, hospital, and other healthcare centers) compared with the ILD population (Fig. 1). In all 3 years, the highest number of billable claims (both ILD-related claims and “any claims”) were made in the physician’s office and hospital settings. In the physician’s office, patients with PF-ILD made 3.0 more ILD-specific claims, and 1.9 more “any claims”, compared with the ILD group (difference in mean average for 3-year period). In the hospital setting, patients with PF-ILD made 5.0 more ILD-specific claims, and 3.5 more “any claims”, compared with the ILD group. In 2016, hospitalization costs per patient for ILD-specific claims were $33,686 in the PF-ILD group versus $17,355 in the ILD group. For all medical claims, hospitalization costs were $77,320 in the PF-ILD group versus $58,245 in the ILD group in the same year (data not shown). Considering all healthcare settings between 2014 and 2016, the majority of medical costs for patients with PF-ILD were associated with hospital claims (83.6%; data not shown).

Discussion

Of the patients identified as having non-IPF ILD, 15% were categorized as having a progressive fibrosing phenotype (PF-ILD) using the proxy of pulmonologist visit frequency. We found that patients with PF-ILD in the USA have higher healthcare utilization and related costs compared with patients who have ILD without a progressive phenotype, suggesting greater disease severity and additional medical care needs for patients with PF-ILD. Medical costs for patients with PF-ILD increased over time, most notably in the “any claims/treatments” category (unfortunately, further details regarding the nature of such claims/treatments were not captured). While this study utilized data from US health records, it is anticipated that patients with PF-ILD in other countries will also have higher healthcare utilization and related costs, compared with patients who have ILD without a progressive phenotype.

In this study, we attempt to define an entity (the progressive phenotype in ILD) that has been poorly defined in the past via healthcare databases, as well as the costs associated with this phenotype in the USA. However, several limitations are acknowledged. One limitation is the use of pulmonologist visit frequency as a proxy to identify patients with a progressive phenotype. Pulmonary function tests, 6-min walking tests, serial high-resolution computed tomography, and assessment of respiratory symptoms would be more accurate and clinically meaningful methods of identifying patients with progressive disease indicative of PF-ILD; however, these data are not collected in ICD codes. In the absence of these data, we felt that pulmonologist visits would be an acceptable surrogate for identifying patients with PF-ILD. Patients who had more pulmonologist visits in 2016 than in 2014 also had an increased frequency of other utilization metrics, indicating severe/worsening disease. While we acknowledge that this approach does not distinguish between patients with severe or worsening disease, we assume some overlap. By default, selecting patients with a higher frequency of pulmonologist visits likely results in a higher cost per patient group. However, in this study it was not the frequency of pulmonologist visits that drove the higher cost in PF-ILD, but rather the cost of making hospital claims.

Although we used the frequency of pulmonologist visits as a proxy measure of progression, it is not possible to say how many visits were scheduled by the pulmonologist as part of standard follow-up or monitoring protocols, and how many resulted from actual or perceived clinical need (as determined by the patients themselves). Frequency of visits may also have been affected by differences in insurance plans and changes in employment status during the study.

Lastly, the 3-year timeframe for data included in these analyses is short (in the absence of historical data, this time period was chosen on the basis of data availability and feasibility). It is acknowledged that a longer study timeframe is necessary for a more meaningful investigation of healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with the disease course of non-IPF ILDs with a progressive fibrosing phenotype. In future, it may prove more informative to conduct longitudinal studies evaluating healthcare resource utilization and medical costs in the year of an ILD diagnosis compared with subsequent time points in later disease. Also, a more detailed analysis of medical costs relating to medications, diagnostic procedures, and supplemental oxygen may provide a more comprehensive and meaningful assessment of healthcare resource utilization than claim-associated costs alone.

Conclusion

Patients with PF-ILD have higher healthcare utilization and related costs when compared with the overall non-IPF ILD population; moreover, these costs appear to increase over time. The data highlight the need for an improvement in the understanding and clinical management of PF-ILDs other than IPF, and we hope that our findings will lead to further, larger-scale investigation of the progressive phenotype in ILD and its associated health costs.

References

Buzan MTA, Pop CM. State of the art in the diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease. Clujul Med. 2015;88(2):116–23.

Valeyre D, Duchemann B, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Annesi-Maesano I. Interstitial lung diseases. In: Annesi-Maesano I, Lundbäck B, Viegi G, editors. Respiratory epidemiology. Lausanne: European Respiratory Society; 2014. p. 79.

Flaherty KR, Brown KK, Wells AU, et al. Design of the PF-ILD trial: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial of nintedanib in patients with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2017;4(1):e000212.

Wells AU, Brown KK, Flaherty KR, Kolb M, Thannickal VJ, IPF Consensus Working Group. What's in a name? That which we call IPF, by any other name would act the same. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(5):1800692.

Hutchinson J, Fogarty A, Hubbard R, McKeever T. Global incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(3):795–806.

Raghu G, Chen SY, Yeh WS, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older: incidence, prevalence, and survival, 2001–11. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(7):566–72.

Fernandez Perez ER, Daniels CE, Schroeder DR, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and clinical course of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a population-based study. Chest. 2010;137(1):129–37.

Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):733–48.

Akira M, Inoue Y, Arai T, Okuma T, Kawata Y. Long-term follow-up high-resolution CT findings in non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Thorax. 2011;66(1):61–5.

Kim EJ, Elicker BM, Maldonado F, et al. Usual interstitial pneumonia in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(6):1322–8.

Khanna D, Tseng CH, Farmani N, et al. Clinical course of lung physiology in patients with scleroderma and interstitial lung disease: analysis of the Scleroderma Lung Study Placebo Group. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2011;63(10):3078–85.

Meyer KC. Diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease. Transl Respir Med. 2014;2:4.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This research, the journals’ rapid service and open access fees were funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH (BI).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. The authors received no direct compensation related to the development of the manuscript. BI was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy, as well as intellectual property considerations.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Writing support was provided by Tom Priddle of Cognito Medical, which was contracted and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Disclosures

Amy Olson has received personal fees from Genentech (for consulting), United Therapeutics (for clinical research) and Boehringer Ingelheim (for clinical research and advisory board participation). Toby M. Maher has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline, Indalo Therapeutics, Pliant Therapeutics, ProMetic, Roche, Samumed and UCB, and stock options from Apellis (his institution has received grants or research fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and UCB). He is currently supported by an NIHR Clinician Scientist Fellowship (NIHR Ref: CS-2013–13-017) and a British Lung Foundation Chair in Respiratory Research (C17-3). Christopher D. Wells has disclosed that he is an employee of Decision Resources Group, which was employed by Boehringer Ingelheim to conduct this research. Valentina Acciai, Baher Mounir, Manuel Quaresma and Leila Zouad-Lejour are all employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. Lou De Loureiro has nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The analyses reported here were based on US-based medical insurance claims and Electronic Health Record data, and do not contain data from any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Permissions to access the database were obtained from the data provider (Decision Resources Group).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the data being from a proprietary DRG data set but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12249695.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Olson, A.L., Maher, T.M., Acciai, V. et al. Healthcare Resources Utilization and Costs of Patients with Non-IPF Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Disease Based on Insurance Claims in the USA. Adv Ther 37, 3292–3298 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01380-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01380-4