Abstract

Introduction

To gain insights into the needs, attitudes, perceptions, and preferences of people living with obesity using an online bulletin board (OBB) study.

Methods

The OBB is a moderated asynchronous online qualitative market research method that allows interactive discussion among participants. Participants were recruited via physician referral followed by screening questions to ensure eligibility and willingness to participate. The discussions in the OBB were moderated and allowed anonymized open answers and responses. Analysis was performed using various qualitative analytical tools.

Results

This OBB study included 23 participants (n = 11, UK; n = 12, USA). Participants expressed negative emotions associated with obesity. Obesity impacted various aspects of their life, and the feeling of loneliness caused food indulgence, especially during the evenings. Their appearance was their primary cause of anxiety, whilst health considerations were secondary. The participants felt trapped in a cycle where food was (ab)used to overcome problems associated with being obese. Participants were pessimistic about weight management measures as a result of unsuccessful past attempts, with little/no support from healthcare providers, friends, and family for weight management. They preferred medications that would allow them to maintain their current lifestyle yet cause visible weight reduction. Along with medications, they expressed a strong preference for an online support group with similar peers for motivation, support, and sustained outcomes.

Conclusions

As losing excess weight is a challenge for most overweight individuals, the qualitative insights from this OBB can inform the planning and successful execution of various weight management and drug development programs.

Funding

Novartis Pharma AG, Basel Switzerland.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The latest position statement from the World Obesity Federation mentions that obesity is a progressive disease process which is both chronic and relapsing. This means that obesity, like other chronic conditions, follows a continuous disease process where diagnosis is made when certain parameters like the body mass index (BMI) are in excess of the “normal range” [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) fact sheet published in 2016, 13% of adults aged 18 years or older (11% among men and 15% among women) are obese. The prevalence of obesity in adults increased by almost threefold between 1975 and 2016 [2], and people living with obesity are at a high risk of developing multiple comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular (CV) diseases, psychiatric disorders, asthma, etc. Obesity along with associated comorbidities not only lowers quality of life and life expectancy but also imposes substantial costs to the healthcare system [3,4,5,6].

As weight gain is a continuous process resulting from a combination of various factors such as excess intake of food, lack of physical activity, and various environmental and genetic factors, losing excess weight and then maintaining the reduced weight is clearly a challenge for people living with obesity [7, 8]. It has been observed that society, in general, has negative perceptions towards people living with obesity. They are viewed unfavorably and are often victims of poor treatment, discrimination, body shaming, and stigmatization [9,10,11,12]. These perceptions and stigmatization create negative bias among people living with obesity, resulting in low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, not seeking medical care, withdrawal from society, and overall poor quality of life [9,10,11,12]. This in turn might cause them to view their condition in a poor light. The negative views they hold and the challenges they face with maintained weight reduction might diminish their motivation to manage weight, leading to lack of adherence to weight management programs, which could be a combination of lifestyle changes and various pharmacological therapies [12]. A deeper understanding of emotional needs, attitudes, perceptions, and preferences of people living with obesity is considered as important to develop and successfully implement various weight management programs [13].

Traditionally, face-to-face focus group discussions have been used to gain insights into patients’ perspectives, needs, and experiences [14,15,16]. Online focus group discussions are gaining popularity with the recent advances in Web-based technology. The online bulletin board (OBB) is a moderated asynchronous online qualitative market research tool that allows virtual interactive focus group discussion and response to predefined questions in a comprehensive and anonymous manner and to generate patient insights [17,18,19]. Various publications have shown the utility of online bulletin or discussion board platforms to study issues in different health conditions [19,20,21]. In this qualitative study we used the OBB approach to gain insights into the needs, perceptions, and attitudinal drivers in people living with obesity.

Methods

This was a 4-day study that involved two OBBs, each with a mixture of participants from the USA and the UK, followed by two 1.5-h telephone group discussions conducted separately with participants from the USA and UK.

Recruitment

Recruitment of individuals living with obesity was done by reaching out to physicians treating these patients for their assistance. The investigators recruited the referred individuals on an opt-in basis based on their profile, a series of screening questions, and a telephone conversation to ensure eligibility and suitability. The participants had to fulfill all the criteria shown in Table 1 in order to be eligible for the study.

The eligible participants were categorized into two study groups (group I and group II), comprising the two OBBs. Participants who had already experienced a CV event were categorized as group I (higher CV risk group) and those without a previous CV event but having certain risk factors were categorized as group II (lower CV risk group). The details of having had a CV event were obtained during the patient screener completion. The hypothesis was that obese participants with a higher CV risk were likely to take their weight management more seriously compared to obese participants who had not experienced a previous CV event. This separation during the screening process generated two separate OBBs, one for each group. The insights obtained from both groups (higher and lower CV risk groups) were combined when the difference in their response was minimal and mentioned separately only when an obvious difference was observed.

This study was conducted within the British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association/The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (BHBIA/ABPI) guidelines following the code of conduct of the Market Research Society (MRS) and European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA). Ethics committee review was not sought for this online patient survey research. Informed consent was obtained electronically from all individual participants included in the study. Participants’ rights and privacy were protected at all times throughout the study. Participants were granted the right to withdraw from the study at any time during the study conduct and to withhold information as they saw fit. All information/data that could identify respondents to third parties was kept strictly confidential; all respondents remained anonymous as their answers were reported in aggregate with the answers of all other participants.

Procedure

Recruited participants were requested to log on to the OBB at least twice a day for at least 30 min each time, for four consecutive days. Participants used self-chosen nicknames rather than their actual names so that the discussion was entirely anonymized. Each day, the participants were provided with a set of questions focusing on a particular theme. The responses were monitored throughout each day by a trained moderator and on the basis of the responses some questions for the next day were modified.

Different types of questions were administered, including mandatory, masked (where a participant would only see other participants’ answers once he or she had answered the question first), open-ended, and closed questions. In addition, participants were also provided with the option to upload images illustrating their feelings about the disease. The length of answers to questions varied from detailed text paragraphs to short confirming answers, such as yes or no. Participants were encouraged to interact with each other through the online platform, comment on each other’s posts, and exchange experiences. Throughout the study, the moderator regularly followed the discussion and posted follow-up questions. Participants had the option to send private notes to the moderator, and could elect not to answer any specific question. At the end of the 4 days, all participants were invited to a 1.5-h follow-up telephone discussion to address any remaining questions and to provide feedback on the OBB.

Insights Sought During the OBB

During the 4 days, the investigators sought to:

-

1.

Explore the participants’ psychological and emotional attitude towards obesity.

-

2.

Identify the presumed causes or “triggers” that the participants believed were responsible for their condition.

-

3.

Understand the burden of obesity on the participants’ daily lives and the challenges that they face with weight management.

-

4.

Identify the weight management approaches they used and participant expectations regarding potential treatment for obesity.

-

5.

Seek information on the kind of support services required, in addition to medication.

Qualitative Analysis of Participant Responses

A combination of different qualitative analytical tools (content analysis, grounded analysis, and discourse analysis) was used to analyze the participant posts on the OBB platform [17,18,19]. For themes or questions where the investigators had initial ideas and hypotheses, content analysis was performed to assess the emerging patterns. The participant inputs obtained were coded and analyzed in a detailed manner. Responses that could not be fit into predefined themes were analyzed using grounded analysis, which helped in identifying areas of further exploration. Finally, discourse analysis was conducted to comprehensively understand the context of participant responses and what the stated information actually meant to them; the OBB approach provided an opportunity to follow up with either individual participants or the group as a whole in this regard. All the responses were consolidated and reported under the respective subject of each day’s discussion, such as (1) participants’ attitude towards obesity and its impact on daily life; (2) participants’ medical and emotional journey uncovering the treatments and measures undertaken to lose weight, including interactions with physicians and their assessment of physician’ attitudes towards obesity; (3) participants’ needs and aspirations, including the type of drug and the optimal treatment outcomes they desired (short- and long-term); and (4) additional support services the participants wished for, to complement the pharmacological treatment.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The OBBs included 23 participants: 11 from the UK and 12 from the USA and aged between 35 and 65 years with a mean (BMI) of 35 (BMI range 30–39). Ten participants (five each from the USA and the UK) had experienced a previous CV event (group I) and 13 participants (seven from the USA and six from the UK) had other comorbidities or risk factors but had not experienced a prior CV event (group II). Table 2 details baseline characteristics of the participants.

Qualitative Insights Gained from the OBB

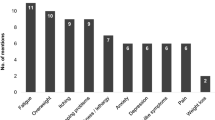

Thoughts About Obesity Triggered Negative Emotions

On day 1, the participants in both the groups expressed a generally positive attitude; as the study progressed, their “true inner feelings” became evident. Though it was observed that the number of participants expressing negative emotions was higher in group II versus group I (13 versus 8), it was inferred that the self-perception of the participants was negative on the whole (Table 3).

Physical and Emotional “Triggers” Resulted in Obesity

All the participants in both groups attributed their weight problem to various physical (e.g., giving birth or accidents that led to reduced mobility) and emotional (seeking comfort in food to overcome troubled relationships, problems at work, or with family) “triggers.” According to the participants these physical and emotional problems caused them to consume more food resulting in weight gain. During the daytime, participants indicated that they “put an act on” to show that all was well. The evenings and nighttime were the periods of maximum struggle, when the participants sought comfort in food to overcome their loneliness, boredom, and stress. A few quotes from participants associated with these findings are listed below:

“I seem to have a handle on my food consumption until nighttime. That is when I lose myself and my control.”

“I think that sometimes boredom kicks in and you crave something just to do.”

“I have trouble sleeping and get up at silly times of the night, and that’s when I begin looking in cupboards, fridge, etc. to find something to eat.”

Impact of Obesity on Daily Lives

Obesity had a psychological bearing and negative impact on the social, intimate, and work life of the all study participants irrespective of their CV risk (Table 4).

Anxiety and Apprehension

A total of 14 participants (5 in group I and 9 in group II) were anxious or apprehensive about their condition (Table 3). External appearance emerged as the primary cause of concern for almost all these participants, as opposed to the medical/health consequences of obesity. Participants from group I were relatively more up-front about having to encounter health issues such as heart problems, stroke, organ failure, T2D, and knee problems, though secondary to appearance. They also talked about reduced life expectancy and mobility, losing independence, and not being there for their children and grandchildren. Compared to group I, participants in group II did not discuss much about the health-related aspects of obesity unless prompted by the moderator to do so.

Measures Undertaken to Lose Weight

Although all participants in both the groups mentioned “diet” as a measure to lose weight, they refrained from mentioning the term “lifestyle changes” spontaneously. In their attempts to manage weight, all the participants in both the groups had tried/were trying different dietary regimens and weight-loss programs, which were often self-selected and not necessarily through medical referral, and often executed irregularly. Approximately 70% of the participants in both the groups sought help from healthcare professionals (HCPs), and almost all of them had tried medications (over the counter and/or prescribed) and also used digital health apps.

The reason to start on a diet or weight-loss program was almost always driven by a short-term goal and linked to a specific future event (e.g., holidays, weddings, Christmas festivities, or meeting someone and wanting to look their best).

The various motivators for the participants to start on a diet are summarized in Table 5. While four participants from group I mentioned health concerns as the primary reason for starting on a diet, none from group II mentioned the same. All group II participants stated that they went on a diet because of emotional/physical reasons.

Challenges Identified by Participants in Losing Weight

It was noted that almost 60% of the participants in both the groups set unrealistic and overambitious weight reduction goals for themselves (Table 6). The participants often tended to complain that their respective diet plans, physical activities, and/or weight-loss medications did not show quick results, resulting in frustration, loss of motivation, and discontinuation.

It was noted that participants were conscious about their appearance and felt embarrassed around other people. This prevented them from visiting the gym, or participating in open meetings or events conducted by organizations to manage weight; rather, they chose to sit at home, and in many cases indulged by finding emotional solace in food. Although a need for lifestyle modifications along with taking medications was understood by the participants, approximately 80% of participants in both the groups found it hard to execute and incorporate it permanently. The lack of adherence was mainly because of an absence of personal drive or motivation and due to the “fear of failing again,” based on their past experiences (Table 6). It was also observed that the participants lacked knowledge (or at least claimed to) on what healthy eating meant.

Those with a history of using weight-loss medications mentioned that they were not persistent with the medications because of the “side effects.” Interestingly, the medications were often blamed to be too short-acting and having a “plateau effect”—significant weight loss in the beginning after which they seemed to stop working and were discontinued. The participants blamed this as the reason for them to regain their lost weight.

The participants also felt that they did not receive enough support from HCPs, friends, or family members to achieve their weight reduction goals. The participants were not satisfied with HCP visits, which included general practitioners (GP), family doctor, dietitian, and/or nutritionist. Approximately 40% of participants in both groups I and II felt that GPs did not see the situation from their perspective and had limited time for them. They felt that HCPs were keen on advocating lifestyle modifications but were reluctant to prescribe weight-loss medications and the participants said that they had to often “proactively” request weight-loss medications. Participants in group I felt that their physicians were usually overly aggressive with their advice, as they were at a higher risk of developing further CV problems. It was also acknowledged that there was limited support from friends or family members to help them adhere to and successfully implement their weight management programs.

Trapped in a Cycle

From the interactions it was inferred that all participants felt “trapped” in a cycle of weight gain and weight loss, from which they thought they could never break free. The participants acknowledged that once they lost some amount of weight it was soon regained. This was primarily because of lack of long-term planning, and lack of guidance and support mechanisms. The weight gain further impacted their daily lives and they turned to the comfort of food more to overcome various physical, emotional, and social problems associated with being obese (Fig. 1).

Needs and Aspirations Regarding Future Treatments

As most of the participants in the study had already tried weight-loss medications in the past, with the feeling they were either “ineffective” or “too short-acting”, they aspired for “a magic pill” that could effectively manage their weight without much effort from their end. Ideally, they desire a drug that would allow them to continue with their old eating and lifestyle habits, whilst helping them achieve their weight goals. Participants also wanted the drug to not have too many “side effects.” The participants tended to categorize their goals into both short- and long-term. The short-term goals identified were noticeable weight loss (1–2 lb lost in a week) along with a reduction in abdominal fat, increased physical fitness, ability to wear nice clothes, and prevention of diabetes or high cholesterol levels. Long-term goals included losing a good amount of body weight by the end of the first year of treatment, without regaining the lost weight again.

Support Systems or Programs

When probed on the additional requirements that were essential to help participants achieve their weight reduction goals, 70% of participants in group I and nearly 40% of participants in group II desired for support systems or programs. Unlike the existing large online weight-loss support groups, which were felt to be targeted primarily at more athletic/fit and healthier individuals, participants expressed a desire for a small local online social group of “people like me,” where they could understand each other’s daily challenges and extend emotional support (similar to the OBB platform), along with a support app for helping them achieve targets. The participants also expressed the need for a moderator (e.g., a nutritionist or a nurse) for such online groups who could check-in regularly, answer questions, share tips, and track progress. The participants also valued having a 24-h toll-free support line as well as some form of encouragement such as e-mails, texts, or a reward program to achieve their weight reduction goals.

Discussion

In the contemporary digital era the use of an OBB platform provides a convenient and effective medium to derive patient insights whilst overcoming geographical restrictions. Earlier we have applied the OBB methodology in various disease areas like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and even very rare conditions like pigmented villonodular synovitis [19, 22,23,24]. One of the key strengths of this methodology is that it maintains patient anonymity, which leads to open-minded, spontaneous, and interactive responses even when dealing with more sensitive topics. Moreover the small and “intimate” size of the OBB group is seen as a success factor for the participants to feel comfortable while exchanging their views with each other and discussing their feelings on topics that they are generally not comfortable to speak about. Thus this approach is helpful to understand more the holistic impact of disease from the patients’ perspective. Our participants too expressed appreciation and gave positive feedback on the OBB methodology.

In accordance with findings from earlier research, we observed that the participants in our study presented with negative emotions associated with their condition which they tend to suppress or hide [25]. As the OBB progressed, the participants tended to express more their inner feelings, and challenges they faced also came to the fore. This behavior could potentially be attributed to the fact that discussions in the OBB setup provided the participants more confidence to speak up and share their problems in a small, relatively close group. However, overall the participants expressed low self-esteem and low confidence because of obesity and the problems associated with it, similar to reports of earlier studies [11, 12, 25,26,27].

Another major finding of our study was that people living with obesity found themselves trapped in a cycle of weight loss and weight gain. Having low self-esteem, low confidence levels, and a sense of feeling embarrassed around others caused participants to become less outgoing and withdraw from society. As reported in earlier studies, our study also showed that loneliness and lack of emotional support along with certain physiological aspects caused participants to seek solace in food, resulting in further increase of weight and low health-related quality of life [11, 12, 28,29,30,31]. This also demotivated them from adhering to their weight management programs [32]. According to participants in our study, even if they managed to get motivated to reduce their weight, it was often for a short time period for which they would mostly choose a dietary regimen. They would “relax” their dietary regime once the date or target is upon them and would revert back to old habits because of lack of motivation and no proper guidance and support—this caused them to regain the lost weight. As reported in previous research, once the lost weight was regained, people living with obesity tended to overeat and abuse food as a way to compensate for the negative impact obesity had on their daily lives, causing patients to feel trapped in a “vicious cycle” [26, 33]. Indeed, this was the primary and the most important challenge highlighted by our study participants, who felt that despite having tried “all possible weight management approaches” numerous times in the past, they either regained the body weight they had lost or ended up becoming more obese (a “yo–yo effect”). These repeated failed attempts in turn led the study participants to believe that they could never break out of the cycle and had effectively given up hope.

Another challenge that our participants felt that prevented them from breaking out of the cycle was the unrealistic and overambitious weight reduction goals that they set for themselves. As seen in previous research, failure to achieve these goals quickly caused annoyance and frustration and reluctance to try any other weight management programs because of the “fear of failing again” [34]. This too caused participants to revert back to their early lifestyle and remain trapped in the cycle.

Our study participants felt that a lack of proper support from HCPs, friends, and family was also a contributing factor for their non-adherence to weight management programs. Previous research has pointed out that the reason for lack of much-needed support from HCPs could be attributed to the existence of bias against obese people in the healthcare establishment [9, 10]. The study participants felt that friends and family members who were themselves not obese would often sabotage their weight-loss attempts through food temptations, as the non-obese could eat what they desired. Studies further indicated that “social pressure” from friends and family members often compels people living with obesity to dine with them and not adhere to a recommended weight management program [32, 35].

The OBB findings also suggest that participants were primarily anxious or apprehensive about their appearance and wanted to lose weight in order to improve “how they looked” and to “fit into nice clothes.” Previous research on obesity has also identified appearance besides health as the main motivator for wanting to lose weight [36]. Notably, the participants in group I were more concerned about health issues associated with their condition than the participants in group II, albeit secondary to their appearance. This was because the participants in group I had already experienced a CV event and felt that they were at a higher risk of developing further complications.

Though study participants identified various physical and emotional “triggers” that caused them to consume more food resulting in weight gain, they were under the notion that medications had to help them achieve their weight reduction goals without much effort from them. Because of this mind-set, they blamed their “past failures” on medications rather than their lack of willpower and perseverance and squarely labelled them as “ineffective.” They sought a “magic pill” that would work long-term with minimal side effects and help them lose excess weight, with minimal effort from their end. Additionally, the participants envisaged a need for support systems or programs such as an online forum of participants (similar to an OBB) on weight management programs and/or on medications and a support app to go with it. This approach would offer emotional support from members having similar issues, as they might be able to convey their feelings and express their emotions openly in a forum, without embarrassment or discrimination. They identified that peer support and motivation was essential to help each other adhere to the diet/exercise plan and lose weight.

We consider that this qualitative OBB study in obesity provides valuable insights. Nevertheless, a few study limitations need a mention. As the number of patients in the OBB was small, the study findings may not be representative of the broader real-world obese population. Of note, qualitative patient preference methodologies typically have small sample sizes and are a scientifically well-established and trusted method of gaining insights around a specific research topic [37, 38]. Though the OBB included a diverse group of patients with different CV risk levels, as a result of the small patient numbers our study did not reveal many differences between patients with differing CV risk propensity; however, this observation needs further investigation with larger sample sizes to draw definitive conclusions. Although this was a short-term exploratory study, the presented findings could be the basis to inform future studies of longer duration that quantitatively analyze patient perceptions from larger patient groups or specific subgroups.

Conclusions

Though we acknowledge that obesity is a continuous disease process dependent on many physiological and psychosocial factors and etiologies, we found that our participants also seemed to lack the knowledge, guidance, and motivation to properly implement weight management programs which are required to help break this cycle of weight loss and weight gain. This is a major challenge facing people living with obesity. Though the participants viewed their condition negatively, they appeared reluctant to modify their lifestyle and food habits permanently. Participants had unsuccessfully undertaken various weight management measures in the past and were apprehensive of trying out new measures because of the fear of failing again. This study provided first-hand information that a drug alone, even with advice from a nutritionist or healthcare professional, might not be enough for sustained outcomes in the absence of a tailored and individualized support program. The OBB methodology was an appealing platform for the participants to express themselves openly and they expressed interest in a support group or program built on similar lines to provide support alongside new therapeutic options.

Notes

BHBIA guidelines: https://www.bhbia.org.uk/guidelines/legalandethicalguidelines.aspx.

ABPI code of practice: http://www.pmcpa.org.uk/thecode/Pages/default.aspx.

MRS code of conduct: https://www.mrs.org.uk/standards/code_of_conduct.

EphMRA code of conduct: https://www.ephmra.org/standards/code-of-conduct/code-of-conduct-online/.

References

Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH, World Obesity Federation. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715–23.

World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Accessed 30 Oct 2017.

Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88.

Rajan TM, Menon V. Psychiatric disorders and obesity: a review of association studies. J Postgrad Med. 2017;63(3):182–90.

Mensink GB, Schienkiewitz A, Haftenberger M, Lampert T, Ziese T, Scheidt-Nave C. Overweight and obesity in Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56(5–6):786–94.

Rudisill C, Charlton J, Booth HP, Gulliford MC. Are healthcare costs from obesity associated with body mass index, comorbidity or depression? Cohort study using electronic health records. Clin Obes. 2016;6(3):225–31.

Montesi L, El Ghoch M, Brodosi L, Calugi S, Marchesini G, Dalle Grave R. Long-term weight loss maintenance for obesity: a multidisciplinary approach. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:37–46.

Qi L, Cho YA. Gene-environment interaction and obesity. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(12):684–94.

Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, van Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16(4):319–26.

World Health Organization. Weight bias and obesity stigma: considerations for the WHO European Region. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases/obesity/publications/2017/weight-bias-and-obesity-stigma-considerations-for-the-who-european-region-2017. Accessed 5 Dec 2017.

O’Brien KS, Latner JD, Puhl RM, et al. The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite. 2016;102:70–6.

Duarte C, Matos M, Stubbs RJ, et al. The impact of shame, self-criticism and social rank on eating behaviours in overweight and obese women participating in a weight management programme. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0167571.

Yoong SL, Carey ML, Sanson-Fisher RW, D’Este CA. A cross-sectional study assessing Australian general practice patients’ intention, reasons and preferences for assistance with losing weight. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:187.

Kennedy-Martin T, Bae JP, Paczkowski R, Freeman E. Health-related quality of life burden of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a robust pragmatic literature review. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;2:28.

Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24:9–18.

LaVela SL, Gallan A. Evaluation and measurement of patient experience. Patient Exp J. 2014;1:28–36.

The Association for Qualitative Research. Online Bulletin Board. https://www.aqr.org.uk/glossary/online-bulletin-board. Accessed 19 Sep 2017.

Green Book Directory. Online Bulletin Board. https://www.greenbook.org/market-research-firms/online-bulletin-boards. Accessed 19 Sep 2017.

Cook NS, Nagar SH, Jain A, et al. Understanding patient preferences and unmet needs in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): insights from a qualitative online bulletin board study. Adv Ther. 2019;36(2):478–91.

Griffiths KM, Reynolds J, Vassallo S. An online, moderated peer-to-peer support bulletin board for depression: user-perceived advantages and disadvantages. JMIR Ment Health. 2015;2(2):e14.

Richard J, Badillo-Amberg I, Zelkowitz P. “So much of this story could be me”: men’s use of support in online infertility discussion boards. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11(3):663–73.

Landskroner K, Walda S, Weiss O, Pallapotu V, Cook N. VP161 identification of needs of pigmented villonodular synovitis patients using online bulletin board. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017;33(S1):222–3.

Cook NS, Gey J, Oezel B, et al. Sleep disturbance and fatigue as consequences of cough and mucus production in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from a patient online bulletin board study. Poster presented at ISPOR Europe [PRS98]; November 10–14, 2018; Barcelona, Spain.

Cook NS, Gey J, Oezel B, et al. Impact of cough and mucus on the emotional and psychosocial wellbeing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative patient online bulletin board study. Poster presented at ISPOR Europe [PRS99]; November 10–14, 2018; Barcelona, Spain.

Görlach MG, Kohlmann S, Shedden-Mora M, Westermann S. Expressive suppression of emotions and overeating in individuals with overweight and obesity. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2016;24(5):377–82.

Pretlow RA. Addiction to highly pleasurable food as a cause of the childhood obesity epidemic: a qualitative Internet study. Eat Disord. 2011;19(4):295–307.

Burrows T, Skinner J, McKenna R, Rollo M. Food addiction, binge eating disorder, and obesity: is there a relationship? Behav Sci (Basel). 2017;7(3):E54.

Klok MD, Jakobsdottir S, Drent ML. The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obes Rev. 2007;8(1):21–34.

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Saunders K, et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):824–30.

Foster GD, Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Brewer G. What is a reasonable weight loss? Patients’ expectations and evaluations of obesity treatment outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(1):79–85.

Tompkins CL, Laurent J, Brock DW. Food addiction: a barrier for effective weight management for obese adolescents. Child Obes. 2017;13(6):462–9.

Sharifi N, Mahdavi R, Ebrahimi-Mameghani M. Perceived barriers to weight loss programs for overweight or obese women. Health Promot Perspect. 2013;3(1):11–22.

Vallis M. Quality of life and psychological well-being in obesity management: improving the odds of success by managing distress. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70(3):196–205.

O’Brien K, Venn BJ, Perry T, et al. Reasons for wanting to lose weight: different strokes for different folks. Eat Behav. 2007;8(1):132–5.

Wang ML, Pbert L, Lemon SC. Influence of family, friend and coworker social support and social undermining on weight gain prevention among adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(9):1973–80.

Cheskin LJ, Donze LF. msJAMA: appearance vs health as motivators for weight loss. JAMA. 2001;286(17):2160.

Hammarberg K, Kirkman M, De Lacey S. Qualitative research methods: when to use them and how to judge them. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(3):498–501.

Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2018.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges (including the open access fee) were funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel Switzerland. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship Contributions

NSC conceptualized the study, and designed the research including the discussion guide together with PT, AB, OW, and SW. OW moderated the online bulletin board during the study, with all authors contributing to the daily review of patient posts and input regarding follow-up questions. ATG, NSC,and PT prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and revision of subsequent drafts and reviewed and approved the final version before submission. All authors are writers of the manuscript and no external assistance for manuscript writing was sought.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

The findings of this study were partly presented as a poster at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) 21st Annual European Congress, 10–14 November, 2018, Barcelona, Spain.

Disclosures

Nigel S. Cook is a full-time employee of Novartis and holds stocks of Novartis. Pradhumna Tripathi is a full-time employee of Novartis. Andrew Bushell is a full-time employee of Novartis. Aneesh T. George is a full-time employee of Novartis. Olivia Weiss is an employee of Ipsos Suisse SA (previously GfK) and declares no conflict of interest. Susann Walda is an employee of Ipsos Suisse SA (previously GfK) and declares no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

This study was conducted within the BHBIAFootnote 1/ABPIFootnote 2 guidelines following the code of conduct of the MRSFootnote 3 and EphMRA.Footnote 4 Ethics committee review was not sought for this online patient survey research. Informed consent was obtained electronically from all individual participants included in the study. Participants’ rights and privacy were protected at all times throughout the study. Participants were granted the right to withdraw from the study at any time during the study conduct and to withhold information as they saw fit. All information/data that could identify respondents to third parties was kept strictly confidential; all respondents remained anonymous as their answers were reported in aggregate with the answers of all other participants.

Data Availability

The datasets (online bulletin board transcripts) generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7660616.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cook, N.S., Tripathi, P., Weiss, O. et al. Patient Needs, Perceptions, and Attitudinal Drivers Associated with Obesity: A Qualitative Online Bulletin Board Study. Adv Ther 36, 842–857 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-00900-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-00900-1