Abstract

Introduction

There is little evidence regarding the most effective timing of augmentation of antidepressants (AD) with antipsychotics (AP) in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) who inadequately respond to first-line AD (inadequate responders). The study’s objective was to understand the association between timing of augmentation of AD with AP and overall healthcare costs in inadequate responders.

Methods

Using the Truven Health MarketScan® Medicaid, Commercial, and Medicare Supplemental databases (7/1/09–12/31/16), we identified adult inadequate responders if they had one of the following indicating incomplete response to initial AD: psychiatric hospitalization or emergency department (ED) visit, initiating psychotherapy, or switching to or adding on a different AD. Two mutually exclusive cohorts were identified on the basis of time from first qualifying event date to first date of augmentation with an AP (index date): 0–6 months (early add-on) and 7–12 months (late add-on). Patients were further required to be continuously enrolled 1 year before (baseline) and 1 year after (follow-up) index date. Patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder diagnoses were excluded. General linear regression was used to estimate adjusted healthcare costs in the early versus late add-on cohort, controlling for baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, insurance type, medications, and ED visits or hospitalizations.

Results

Of the 6935 identified inadequate responders, 68.7% started an AP early and 31.3% late. At baseline, before AP augmentation, patients in the early add-on cohort had higher psychiatric comorbid disease burden (47.3% vs. 42.5%; p < 0.001) and higher inpatient utilization [mean (SD) 0.41 (0.72) vs. 0.27 (0.67); p < 0.001] than in late add-on cohort. During follow-up, the adjusted total all-cause healthcare cost was significantly lower in the early vs. late add-on cohort ($18,864 vs. $20,452; p = 0.046).

Conclusion

Findings of this real-world study suggest that, in patients with MDD who inadequately responded to first-line AD treatment, adding an AP earlier reduces overall healthcare costs.

Funding

Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc. and Lundbeck.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) has a lifetime prevalence of 16% among adults in the USA and an estimated annual cost of $83 billion [1, 2]. Adequate treatment of MDD remains a significant challenge. Results from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study indicated that the probability of depression remission decreases significantly after the failure of two treatment trials. About 60% of patients who continue for a second course of treatment do not respond, and after four trials, about 30% of patients remain depressed [3].

Incomplete remission of depression is associated with a higher risk of relapse, impaired work and social functioning, and an increased risk of suicide [4]. The World Health Organization rated unipolar depressive disorders as the third leading cause of disability-adjusted life years, which disproportionately accrues to individuals who have either not responded or only partially responded to first-line antidepressant (AD) treatment [2].

With patients suffering from lack of adequate response accounting for a large share of the MDD burden, developing safe and effective treatments is of great importance. Two main treatment strategies have been recommended for patients who are inadequately responding to first-line AD. These include switching to a different AD, favored for nonresponse [5], or augmentation with an atypical antipsychotic (AP) medication, lithium, or thyroid hormone, preferred in cases of partial response [6]. The American Psychiatric Association guidelines [7] designate the same level of confidence for augmentation with atypical APs, lithium, thyroid hormone, or another AD; however, among these agents, atypical APs have been studied in the largest number of randomized controlled trials using well-defined samples of patients with MDD [8]. In fact, the recently published Veterans Affairs Augmentation and Switching Treatments for Improving Depression Outcomes (VAST-D) trial compared augmentation with an atypical AP to an AD switch and found a slight benefit to augmentation over AD switch [9]. Prior studies focusing on inadequate treatment efficacy in MDD included patients of varying disease severity; some patients have experienced inadequate response to one AD, while others have not responded to up to four ADs [10].

The aim of this exploratory analysis was to understand the association between timing (early vs. late) of augmentation of AD with APs and overall healthcare cost in patients with MDD following an event indicative of inadequate depression treatment efficacy (inadequate responders). In this study, we characterized events occurring prior to the addition of the adjunctive AP medication. These events were considered proxies for inadequate treatment efficacy and included AD switches or add-ons, initiation of psychotherapy, or psychiatric hospitalization or emergency department (ED) visit.

Methods

Data Source and Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Truven Health MarketScan® Medicaid, Commercial, and Medicare Supplemental claims databases to compare healthcare costs in patients who initiated an oral AP presumably because of inadequate response to first-line ADs. The MarketScan Medicaid Database includes demographic and clinical information, inpatient and outpatient utilization data, and outpatient prescription data for 40 million Medicaid enrollees from multiple geographically dispersed states. To ensure complete medical claims histories, patients with Medicare dual-eligibility, capitated health insurance, or without mental health coverage were excluded. The MarketScan Commercial Database includes medical and pharmacy claims for approximately 65 million individuals and their dependents who are covered through employer-sponsored private health insurance plans. The MarketScan Medicare Supplemental Database contains records on about 5.3 million retired employees and spouses older than 65 years who are enrolled in Medicare with supplemental Medigap insurance paid by their former employers.

The study used medical, pharmacy, and enrollment claims from 7/1/09 through 12/31/16 for Medicaid data and 7/1/09 through 9/30/16 for Commercial and Medicare Supplemental data. All data were compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. Institutional review board approval was not required as MarketScan data are recorded in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects. Meeting these conditions makes this research exempt from the requirements of 45 CFR 46 under the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS): “Research, involving the collection or study of existing data, documents, records, pathological specimens, if these sources are publicly available or if the information is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects [11].” This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Sample Selection

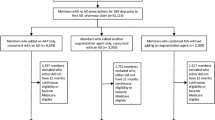

Patients with a diagnosis of MDD were identified if they had at least one inpatient or two outpatient medical claims for MDD (International Classification of Disease—Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code: 296.2x, 296.3x; ICD-10-CM: F32.0-F32.5, F32.9, F33.0x-F33.4x, F33.9x; see Appendix Table 1 for full list of codes with descriptions) in any diagnosis field of a claim between 7/1/09 and 12/31/16 (Medicaid) or 7/1/09 through 9/30/16 (Commercial and Medicare Supplemental). Patients must have had evidence of inadequate treatment efficacy during the clinical event identification period (10/1/09–12/31/14 for Medicaid data, and 10/1/09–9/30/14 for Commercial and Medicare Supplemental data). These inadequate treatment efficacy events (“clinical events”) included psychiatric hospitalization, psychiatric ED visits, initiation of psychotherapy, and AD class-level switches or augmentation (see Appendices Tables 2 and 3 for full lists of codes with descriptions). Patients with qualifying clinical events were required to have at least one AD medication claim during the 90 days prior to the first of the clinical events to ensure that this was a medically treated population. Only the first qualifying event for each patient was captured.

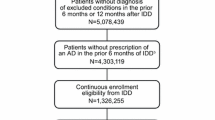

The index date, or the first date of augmentation with an oral AP, was captured up to 12 months from the clinical event. Patients were grouped into the following two cohorts based on time from first qualifying clinical event date to first date of augmentation with an AP: 0–6 months (early add-on) and 7–12 months (late add-on). All patients were required to have at least 60 days of the AP medication use within the 6 months following the index date. Additionally, to ensure that the AP was being utilized as adjunctive treatment, patients were required to have at least one AD pharmacy claim each in the 90 days prior and the 90 days after the index date, with at least 15 days overlap of AD supply with the first index oral AP prescription. Patients using combination AP therapy or those who had utilized AP medication prior to the index date were not included in the study sample. The baseline and follow-up periods were defined as the 12 months before and after the index date, respectively (Fig. 1).

Study timeline for patients with MDD who initiated adjunctive antipsychotic early vs late. The index date, or the first date of augmentation with an oral AP, was captured up to 12 months from the clinical event. All patients were required to have at least 60 days of the AP medication use within the 6 months following the index date. Additionally, to ensure that the AP was being utilized as adjunctive treatment, patients were required to have at least one AD pharmacy claim each in the 90 days prior and the 90 days after the index date, with at least 15 days overlap of AD supply with the first index oral AP prescription. The baseline and follow-up periods were defined as the 12 months before and after the index date, respectively. *Includes ED visits, hospital stays, initiation of psychotherapy, and/or antidepressant switches. C commercial, MC medicaid, mo months, SUP Medicare Supplemental

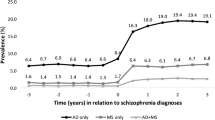

Further, eligible patients were at least 18 years of age on the index date, had their first diagnosis of MDD on or before the index date, and fulfilled the requirement of 12 months of continuous enrollment both during the baseline and follow-up periods. Patients were excluded if they had at least one diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM codes: 295.xx, excluding 295.4x and 295.7x; or ICD-10-CM codes: F20x, excluding F20.81) or bipolar I disorder (ICD-9-CM codes: 296.0x, 296.1x, 296.4x-296.8x, excluding 296.82; or ICD-10-CM codes: F30.x-F31.x, excluding F31.81) anytime during the study period to account for the potentially different resource utilization and treatment patterns of these patients, compared to patients with MDD only.

Study Measures

Baseline variables, which employed data during the 12 months prior to the index date, included patient demographics (age, gender, and insurance type), event type, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [12, 13], number of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) chronic condition indicators [14], psychiatric comorbidities (anxiety, personality disorder, and substance abuse disorder), psychiatric (antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications, sedatives or hypnotics, and mood stabilizers) and non-psychiatric (antidiabetic, lipid-lowering, and antihypertensive medications) medication use, ED visits, and hospitalizations. Unlike our patient identification algorithm (which required one inpatient or two outpatient claims for MDD), when we identified patients as having psychiatric comorbidities (anxiety, personality disorder, and substance abuse disorder), the presence of a single code during the baseline period for the relevant condition was considered adequate.

The main outcome of interest was all-cause total healthcare cost and its components during the 12-month follow-up period. Total cost consisted of three main components: outpatient medical cost (outpatient and ED visits), inpatient cost (acute and non-acute inpatient stays), and outpatient pharmacy cost. Additionally, we analyzed inpatient costs among patients who experienced at least one hospitalization. All outcomes were compared between the early and late add-on study cohorts.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to assess differences between cohorts across all baseline covariates, including means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables, and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests and t tests were utilized as appropriate. General linear regression was used to estimate the all-cause total cost during the 12-month follow-up period. Baseline covariates included age, gender, insurance type, event type, CCI, number of chronic conditions, psychiatric comorbidities (anxiety, personality disorder, substance abuse disorder), baseline psychiatric medication use (serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], tricyclic or tetracyclic agents, antianxiety medications, sedatives or hypnotics, mood stabilizers), hospitalizations, ED visits, and index AP class (atypical, typical). Beta coefficients, p values, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for model covariates were provided. All costs were adjusted to 2016 US dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index. All data transformations and statistical analyses were performed using SAS© version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Sample Description

Of the 1,868,031 patients with MDD without schizophrenia or bipolar disorder as comorbidities identified from the combined dataset (Medicaid, Commercial, and Medicare Supplemental), 515,478 experienced a clinical event indicating inadequate treatment efficacy while taking an AD. There were 86,610 patients that had evidence of AP use within 12 months after the clinical event date. Of those patients, 30,884 had no AP use prior to the index date and filled at least 60 days of the index AP within 6 months of the index date. In total, 6935 patients met all inclusion requirements.

The most commonly prescribed index APs in this population were aripiprazole (53.4%), quetiapine (28.0%), risperidone (9.5%), olanzapine (4.8%), and ziprasidone (1.3%). All other AP medications collectively comprised less than 5% of index AP. The early add-on cohort included 4762 (68.7%) patients and the late add-on cohort consisted of 2173 (31.3%) patients.

Baseline Characteristics

The mean age of the overall sample was 49.5 years; 68.3% of patients were female, 74.7% carried Commercial insurance, and 45.8% suffered from at least one psychiatric comorbidity (other than schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, as they were excluded), with anxiety (40.3%) being the most common. Baseline hospitalizations occurred in 28.3% of patients, and 23.5% had a baseline ED visit. The most prevalent clinical event was initiation of psychotherapy (42.7%). Patients in the early and late add-on cohorts differed significantly in gender, insurance type, clinical event, psychiatric comorbidities and medication use, and baseline utilization. The early add-on cohort comprised a lower percentage of women, Medicaid patients, patients who experienced an AD switch or add-on, patients prescribed SNRIs, other AD, mood stabilizers, and non-psychiatric medications; and a greater percentage of patients prescribed SSRIs and sedatives and hypnotics, patients with anxiety and substance abuse, and patients with ED visits and hospitalizations (p < 0.05 for all comparisons) (Table 1).

Timing of Antipsychotic Initiation and All-Cause Cost: Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

The mean unadjusted all-cause cost during the 12-month follow-up period was not statistically significantly different when comparing the early and late add-on cohorts [mean (SD): $18,842 (27,886) vs. $20,500 (38,127) p = 0.069]. While all components of the total cost were numerically lower in the early add-on cohort, the difference was only statistically significant for outpatient pharmacy costs [mean (SD): $6328 (6185) vs. $7091 (6305), p < 0.001]. The cost of hospitalization among those who were hospitalized in the early add-on cohort was $24,138 (39,296) vs. $30,516 (67,037) in the late add-on cohort (p = 0.054) (Table 2).

After adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics, the timing of adjunctive AP initiation (early vs. late cohort) was a significant predictor of all-cause cost. The early add-on cohort incurred $1587 less in total during the 12-month follow-up period (95% CI − 3148 to − 26) than the late add-on cohort. The adjusted total all-cause cost was $18,864 for the early add-on cohort and $20,452 for the late add-on cohort (Table 3).

Discussion

We performed an exploratory analysis to investigate cost outcomes in patients who initiated an oral AP medication early versus late following an event suggestive of inadequate depression treatment efficacy. The early add-on cohort seemed to be sicker and have a greater burden of psychiatric disease. Considering the triggering events denoting treatment inadequacy, higher percentages of patients in the early add-on cohort experienced a psychiatric admission or ED visit, as well as initiation of psychotherapy; a lower percentage of patients in the early add-on cohort switched or added on an AD, when compared with the late add-on cohort. Further, on univariate analysis of baseline characteristics, the early add-on cohort also showed signs of more complicated psychiatric disease, reflected as higher rates of psychiatric comorbidities; however, this result is tempered by the incorporation of psychiatric exclusion criteria. In multivariate analysis, the patients who initiated an oral AP medication early (within 6 months) demonstrated lower all-cause total healthcare costs during the ensuing 12 months, compared to those who were prescribed an oral AP later [mean (SD) $18,864 (18,004–19,725) vs. $20,452 (19,167–21,736), p = 0.046].

The early add-on cohort in this retrospective study was associated with lower total all-cause cost during the first year of AP use, suggesting that earlier augmentation could decrease costs. If further studies were to support these findings, it would suggest that earlier augmentation with AP medication could be superior to AD switch in patients with inadequate response to ADs. This finding is consistent with the emerging evidence of benefit to augmentation over AD switch [9]. Patients in the early add-on cohort had lower percentages of AD switches and add-ons prior to initiation of AP medication, as compared with the late add-on cohort (37.2% vs. 49.7%, p < 0.001). Although all patients in this study were prescribed oral AP augmentation, it is possible the early add-on cohort consisted of patients who were more rapidly augmented with oral APs and may have experienced fewer trials of AD switches. Instead of focusing on the number of failed AD trials, we characterized the absolute timing from an event indicating suboptimal response to current therapy, and the associated economic effects, adding these important data to the literature.

Our observations suggest that physicians are adhering to the evidence and augmenting more complicated or less treatment-responsive patients earlier than those who are less severe. The early add-on cohort had more complex psychiatric disease and tended toward ED visits and inpatient admissions; patients in the early add-on cohort experienced a psychiatric-related hospitalization prior to AP initiation at nearly three times the rate of the late add-on cohort (14.9% vs. 5.2%, p < 0.001). The faster onset and improved effects of adjunctive APs may be related to why these more severe patients initiated these medications earlier. AP medications are known for their relatively rapid onset, showing clinical benefits within 1–2 weeks [15], and these effects are at doses as low as a quarter to half of those used to treat acute schizophrenia or mania [16]. A recent study found that augmentation with an atypical AP medication demonstrated added benefit in patients with a higher degree of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) [17]. Further, a study by McIntyre et al., based on physician surveys, found that one of the main predictive factors that led to the prescription of an AP medication in MDD was severity of illness [18]. Using insurance claims data, our findings demonstrate higher rates of patients with more severe disease undergoing earlier AP augmentation, validating the results of the previous survey-based study.

The adjusted all-cause total costs for the 1-year period following oral AP initiation were $18,864 for the early add-on cohort and $20,452 for the late add-on cohort; these values provide an updated cost of MDD treated with oral APs. A previous study utilizing data from the Medicare population with managed depression found the yearly total cost to be $13,252 [19]. Since this cohort comprised patients with managed depression, it is likely that less severe, and therefore, less expensive patients are included. Halpern et al. investigated total medical costs of various adjunctive APs in a commercial population; the 1-year costs ranged from $10,664 to $14,583 [20]. Our costs were higher than these studies, which could stem from the dataset utilized. Our study population combined patients with Medicaid, Medicare, and Commercial insurance. The study by Halpern et al. better matches our methodology, in that costs are measured from the initiation of the AP medication; however, this study was performed using a population with Commercial insurance, likely causing the costs to be lower. Additionally, the previous analyses were performed several years prior and healthcare costs have continued to increase over time.

Several limitations of this study stem from the health insurance claims dataset utilized. First, we were unable to directly measure disease severity; we were not only unable to ascertain the level of a patient’s MDD but also could not determine when a patient entered remission. We did, however, use a variety of measures to adjust for severity, including baseline non-psychiatric and psychiatric comorbidities, pre-index event, medication use, and inpatient and ED utilization. There may have been additional differences we could not measure or adjust for in models. Second, because we were unable to assess MDD severity directly, we identified proxies indicative of inadequate treatment efficacy, such as psychiatric hospitalizations or ED visits. Third, increased rates of side effects, when compared to ADs, are an important aspect of AP use to identify when investigating the outcomes surrounding augmentation and switching. Insurance claims data are not an ideal source to capture patients who discontinued AP medications secondary to side effects or intolerability. In fact, given the requirement for at least 60 days of AP use during the 6 months following the index date, many patients who may have suffered from intolerable side effects were likely excluded from the analysis. This requirement was employed as a way to fairly adjust for the severity of the study population; a patient who utilized only a week of AP medication likely had different experiences and costs than a patient who adhered for several months. Lastly, all MDD diagnoses were identified through health insurance claims data, where misclassification, diagnostic uncertainty, or coding errors are possible. Although claims data do have the aforementioned limitations, studies utilizing these data include more diverse individuals who may better characterize conditions and their treatment in a real-world setting, as opposed to the relatively homogenous populations that tend to comprise clinical trials. Despite these limitations, we believe that this initial exploratory analysis provides valuable insight into cost outcomes associated with the timing of oral AP augmentation.

Conclusions

This study investigated the differences between patients with MDD who initiated oral AP augmentation early versus late following an event indicative of inadequate depression treatment efficacy. Patients in the early add-on cohort, despite their higher levels of both baseline psychiatric comorbidities and hospitalizations, had significantly lower costs during the 1-year period following oral AP medication initiation in a real-world study of a population that combined patients with Medicaid, Medicare, and Commercial insurance. Further studies are warranted to more thoroughly characterize this association between earlier oral AP medication initiation and lower all-cause total cost.

References

Kennedy SH. A review of antidepressant therapy in primary care: current practices and future directions. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(2). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.12r01420.

McIntyre RS, Filteau M-J, Martin L, et al. Treatment-resistant depression: definitions, review of the evidence, and algorithmic approach. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1–7.

Rush A, Trivedi M, Wisniewski S, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–17.

Thase ME. Treatment-resistant depression: prevalence, risk factors, and treatment strategies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:e18.

Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. Acceptability of second-step treatments to depressed outpatients: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:753–60.

Shelton RC, Osuntokun O, Heinloth AN, Corya SA. Therapeutic options for treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2010;24:131–61.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2010.

Patkar AA, Pae C-U. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation strategies in the context of guideline-based care for the treatment of major depressive disorder. CNS Drugs. 2013;27:29–37.

Mohamed S, Johnson GR, Chen P, et al. Effect of antidepressant switching vs augmentation on remission among patients with major depressive disorder unresponsive to antidepressant treatment: the VAST-D randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:132.

Zhou X, Ravindran AV, Qin B, et al. Comparative efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of augmentation agents in treatment-resistant depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;e487–98.

Office for Human Research Protections. Coded private information or specimens use in research, guidance (2008). HHS.gov. 2008. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/research-involving-coded-private-information/index.html. Accessed 26 Oct 2018.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP chronic condition indicator. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. HCUP. 2015. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. Accessed 22 May 2018.

Thase ME. Adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics as adjuncts to antidepressants. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39:477–86.

Connolly KR, Thase ME. If at first you donʼt succeed: a review of the evidence for antidepressant augmentation, combination and switching strategies. Drugs. 2011;71:43–64.

Wang HR, Woo YS, Ahn HS, Ahn IM, Kim HJ, Bahk W-M. Can atypical antipsychotic augmentation reduce subsequent treatment failure more effectively among depressed patients with a higher degree of treatment resistance? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18(8). https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyv023.

McIntyre RS, Weiller E. Real-world determinants of adjunctive antipsychotic prescribing for patients with major depressive disorder and inadequate response to antidepressants: a case review study. Adv Ther. 2015;32:429–44.

Feldman RL, Dunner DL, Muller JS, Stone DA. Medicare patient experience with vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. J Med Econ. 2013;16:62–74.

Halpern R, Nadkarni A, Kalsekar I, et al. Medical costs and hospitalizations among patients with depression treated with adjunctive atypical antipsychotic therapy: an analysis of health insurance claims data. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:933–45.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Funding for the study and article processing fees were received from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc. and Lundbeck. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

All authors met the ICMJE criteria for authorship, including contributing to study concept and design, interpretation of the data, and to the drafting and critical review of the manuscript. E. Chang further contributed to the analysis of the data. This manuscript has been read and approved by all authors.

Disclosures

Michael S. Broder is an employee of PHAR, LLC, which was paid by Otsuka and Lundbeck to perform the research described in this manuscript. Tingjian Yan is an employee of PHAR, LLC, which was paid by Otsuka and Lundbeck to perform the research described in this manuscript. Eunice Chang is an employee of PHAR, LLC, which was paid by Otsuka and Lundbeck to perform the research described in this manuscript. Irina Yermilov is an employee of PHAR, LLC, which was paid by Otsuka and Lundbeck to perform the research described in this manuscript. Mallik Greene is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc. Ann Hartry is an employee of Lundbeck.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as the Truven Health data were used under license for the current study, but are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Truven Health.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7297541.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Yermilov, I., Greene, M., Chang, E. et al. Earlier Versus Later Augmentation with an Antipsychotic Medication in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder Demonstrating Inadequate Efficacy in Response to Antidepressants: A Retrospective Analysis of US Claims Data. Adv Ther 35, 2138–2151 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0838-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0838-2