Abstract

The present paper deals with preform deformation and resin flow coupled to cure kinetics and chemo-rheology for the VARTM process. By monitoring the coupled resin infusion and curing steps through temperature control, our primary aim is to reduce the cycle time of the process. The analysis is based on the two-phase porous media flow and the preform deformation extended with cure kinetics and heat transfer. A novel feature is the consideration of temperature and preform deformation coupled to resin viscosity and permeability in the VARTM process. To tackle this problem, we extend the porous media framework with the heat transfer and chemical reaction, involving additional convection terms to describe the proper interactions with the resin flow. Shell kinematics is applied to thin-walled preforms, which significantly reduces the problem size. The proposed finite element discretized system of coupled models is solved in a staggered way to handle the partially saturated flow front under non-isothermal conditions efficiently. From the numerical example, we conclude that the cycle time of the VARTM infusion process can be shortened over 68% with the proper temperature control. Moreover, the proposed framework can be applied to optimize the processing parameters and check the compatibility of a resin system for a given infusion task.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

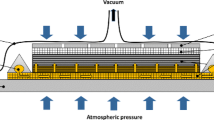

Nowadays, the vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding (VARTM) process is extensively used to produce fiber-reinforced polymer composites. It has the benefits of the enclosed volatile organic compounds emission, high flexibility, scalability, and affordability [1]. The VARTM process mainly consists of two stages, 1) the liquid thermoset resin infusion, and 2) the resin curing stage. The viscous resin is infused into the pre-compacted porous fiber preform by the pressure difference between atmospheric pressure and the vacuum inside the flexible bag. In this stage, void formation and thickness variation are the main challenges. Those are primarily related to various process parameters, such as the arrangement of inlets and vents, the permeability of the preform, the viscosity of the resin, and the geometry of the mold. The liquid thermoset resin is cured after the infusion stage. At this stage, the liquid resin turns to solid polymer networks, which is also named cross-linking. The irreversible curing stage is usually carried out under the designed combinations of pressure, temperature and time, which are known as cure cycles. An inadequate curing cycle may lead to the problems of residual stress, spring-in/spring-back, and void formation. A major challenge in the VARTM process design is to reduce the cycle time for both the infusion and curing stages and enhance the quality of final parts. To this end, researchers are developing models and numerical methods to assist the design and optimization of the holistic process via simulations.

The entire two-stage VARTM process is usually modeled separately. The resin infusion can be modeled as the problem of the resin flow transportation in porous media. Hsiao, Mathur, Advani, Gillespie & Fink [2] developed a closed-form solution for the VARTM resin flow. Besides, Wu & Larsson [3] reported a model of homogenized free surface flow in porous media for wet-out processing. What is more, Simacek & Advani [4] and Zhou, Alms & Advani [5] contributed methods of modeling dual-scale flow. To consider the deformation of the flexible vacuum bag, Loudad, Saouab, Beauchene, Agogue & Desjoyeaux [6] reported a multi-layer model. Chevalier, Bruchon, Moulin, Liotier & Drapier [7] integrated capillary actions into a general bi-fluid model. Moreover, Wu & Larsson [8] suggested a shell model that is capable of simulating both the resin flow and the lubrication and relaxation mechanisms of the preform during the VARTM process. These models have reported good agreements with the initial experiments, e.g., [9]. However, the models, as mentioned above, are limited to the isothermal condition. The onset of curing during the infusion stage has therefore been ignored.

To model and simulate the resin curing stage, many researchers have proposed a variety of cure kinetic and chemo-rheological models. Kamal & Sourour [10] and Bogetti & Gillespie [11] were the pioneers who proposed the most frequently used cure kinetics models. In addition, Stanko & Stommel [12] and Tao, Pinter, Antretter, Krivec & Fuchs [13] applied the Model Free Kinetics approach to model the curing under both non-isothermal and isothermal heating conditions. The curing processes of different processes and composite materials have been studied. Ruiz & Trochu [14] presented a reaction kinetics model for the Resin Transfer Molding (RTM) process. Muc, Romanowicz & Chwałl [15] reported optimization of the RTM curing process. Benavente, Marcin, Courtois, Lévesque & Ruiz [16] reported a model to predict the geometrical distortion during cure cycles. Moreover, the cure kinetics model for the autoclave molding process has been reported by Maji & Neogi [17]. As to the out-of-autoclave process, Dong, Zhao, Zhao & Yu [18] developed a fast curing model. Garschke, Parlevliet, Weimer & Fox [19] studied the curing stage of the out-of-autoclave (OOA) toughened resin film infusion (RFI) process. Guo, Du & Zhang [20] and Hwang, Park, Kwon & Choi [21] studied the curing stage of the Vacuum Bag Only (VBO) process. Park, Choi, Choi & Hwang [22] compared the autoclave and OOA curing of the VBO process.

On the other hand, concerning the viscosity, the Castro-Macosko model [23] is one of the most extensively well-known chemo-rheological models. Researchers propose many chemo-rheological models as well. Henne, Breyer, Niedermeier, & Ermanni [24] proposed a model having a higher dependency on the temperature and degree of cure. In addition, He, He, Ma & Guo [25] developed a viscosity model for almost the entire curing range. On the other hand, Li & Zhang [26] obtained viscosities of epoxy resin at each curing degree using the “viscosity-cure” shift function. Zhang, Zhao & Zhang [27] discovered the temperature-time regulation of viscosity. The Williams-Landel-Ferry (WLF) equation is applied by Karkanas & Partridge [28] to model the viscosity. Pandiyan & Neogi [29] performed a nonlinear-regression analysis of viscosity and degree of cure data to quantify the dependence of viscosity on temperature and extent of cure reaction. Geissberger, Maldonado, Bahamonde, Keller, Dransfeld & Masania [30] reported a time-dependent chemo-rheological model without the knowledge of the cure kinetics.

The studies mentioned above either aimed at the infusion stage or the curing process independently; however, in fact, the resin flow development, heat transfer, and resin cure are strongly interrelated at both stages. The exothermic reactions increase resin temperature – additionally change the viscosity, which in turn affect the flow filling pattern. Moreover, the degree of cure upon the completion of the infusion stage contributes to the initial conditions for the curing stage. The reduction of the process cycle time may benefit from the adequate control of the temperature and initialization of polymerization. In those regards, Celle, Drapier & Bergheau [31] modeled the non-isothermal fluid flow during the RFI process omitting the changes of resin viscosity. Keller, Dransfeld & Masania [32] proposed a framework to simulate the flow and heat transfer during the Compression Resin Transfer Molding (CRTM) process. Shi & Dong [33] and Yang, Lu, Xian & Liu simulated the filling and curing processes in the non-isothermal RTM process. So far, the holistic simulation of the VARTM process has rarely been reported. Grujicic, Chittajallu & Walsh [34] and Ma, Athreya, Mehta, Barpanda & Shafi [35] simulated the non-isothermal VARTM process of large and thick composite parts. However, the consideration of the multi-phase flow, the capillary effect, and mathematical models of preform deformations are absent in those works. Based on the previous shell model [8], we include the cure kinetics, chemo-rheological model, and heat transfer in this study to simulate both the filling and curing stages in the non-isothermal VARTM process. By virtue of the simplified shell model, we propose a system of coupled models that can efficiently simulate and predict the flow pattern, pressure, temperature, degree of cure, viscosity, and preform deformation in the course of non-isothermal VARTM process for the thin-walled preform. Through the numerical experiment, we also show the potential of initiating polymerization during the infusion stage to optimize the total process cycle time. In the numerical experiment, the thermoset resin and carbon NCF preform are studied initially. Besides, the emerging reactive thermoplastic resin is considered. Because the viscosity of the reactive thermoplastic liquid methyl-methacrylate resin [36] is as low as the thermoset polymer at room temperature, it can be processed directly by the VARTM process. On the other hand, the polymerized thermoplastics can be melted. Based on this characteristic, the numerical experiment discusses the possibility of accelerating the VARTM process using reactive thermoplastic resin under high temperature.

The paper is organized as follows: in “Governing equations”, we present the mathematical models, followed by numerical simulation in “Numerical simulation”. Furthermore, the results from the simulation are compared and discussed in “Results and discussion”. Finally, the concluding remarks are made in “Conclusion”.

Governing equations

In this section, we outline the flow model, the energy equation, the cure kinetics, and chemo-rheological models. Concerning the non-isothermal VARTM process, we assume

-

1.

the preform is considered as thin-walled and the through-thickness flow is neglected [8];

-

2.

the heat transfer between the preform and resin/air mixture fluid are instantaneous [37];

-

3.

the viscosity dissipation energy in the energy equation is neglected [33];

-

4.

the gravity is neglected;

-

5.

the infusion is stopped when the mold is filled.

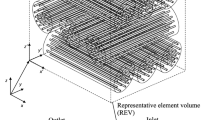

Model of resin infusion in the deformable preform

The flow front position is identified using the concept of saturation degree. Let ns and nf represent the volume fraction of fibers and the mixture fluid of liquid and air, respectively, which satisfies

The mixture fluid is further divided by the saturation degree, 0 ≤ ξ ≤ 1, as

where φl := ξnf denotes the liquid volume fraction, and φg := (1 − ξ)nf is the air volume fraction. The homogenized state variables can be expressed following the homogenization approach from [3]

where χ stands for the density – ρ, viscosity – μ, thermal conductivity – k, and specific heat capacity – cp.

Two equations from the mass balance relation have been derived from [8], i.e., the saturation equation

and the pressure equation,

In Eqs. 4 and 5, J is the Jacobian of the deformation gradient tensor F, which is defined as

where I is the second order identity tensor, N is the normal of the preform top surface, and \(\lambda := \frac {h}{h_{0}} = J\) denotes the ratio between the deformed preform thicknesses h and the un-deformed preform thicknesses h0 [8]. The Darcy velocity of the homogenized fluid, vdf, is expressed as

where \(\hat {\boldsymbol {k}}\) is the intrinsic permeability tensor of the preform. The relative permeabilities of resin, \({k}_{\mathrm {r}}^{l}\), and gas, \({k}_{\mathrm {r}}^{g}\), are obtained from [38], respectively

Equations 8 and 9 are derived from the Brooks and Corey’s [39] capillary pressure model,

where pc is the capillary pressure, the pressure of air is represented by pg and the pressure of resin is denoted as pl. The entry pressure pent and the parameter nb control the capillary pressure curve.

Fiber preform compaction model

From [8] and [9], we obtain a constitutive relation between the fluid pressure and the fiber preform stretch,

where ksE and m are parameters in the Toll’s packing law [40], the atmospheric pressure is represented by pa, the volume fraction of the un-deformed fiber preform is denoted as \({n}_{0}^{s}\). We emphasize that Eq. 11 is based on an exponential hyper-elastic law that describes the fiber packing in terms of the fiber volume fraction ns, cf. [8].

As long as the preform compacts or expands during the VARTM process, ns and nf are varying accordingly,

Thus, the permeability variations can be expressed using the Kozeny-Carman equation as

where \(\hat {k}_{ij}\) is the in-plane principle permeabilities, where i = 1,2, and j = 1,2.

Cure kinetics and chemo-rheological models

The Kamal and Sourour [10] autocatalytic model is modified with the diffusion factor to improve the cure kinetics at the final cross-linking stage as

where the function G denotes the rate of change of degree of cure, c is the degree of cure, T is the resin temperature. cd denotes the diffusion control factor, and cc is the critical degree of conversion, n1 and n2 are the overall reaction orders. k1 and k2 are the specific rate constants given by Arrhenius expressions,

where Ai is the pre-exponential factor, Ei is the activation energy, and R is the universal gas constant.

Given the fact that the cure reaction is moving as the fluid is transporting in the porous fiber preform, the degree of cure for a given temperature, T, depends on both time and positions of the flow, i.e., \(c:= c\left [ \boldsymbol {x},t\right ] \). We derive (16) from the mass balance of the cured resin (see Appendix A) following the theory of porous media as

When the preform is fixed, we have vs = 0. Thus (16) reduces to the form reported in [37, 41, 42] as

where De is the effective diffusivity tensor, and DD is the hydrodynamic dispersion tensor, which are defined as

where D = 8.2 × 10− 12m2/s is the molecular diffusion coefficient of the resin [43], I is the second order identity tensor.

where \( D_{\mathrm {D}}^{\parallel }=0.357 P e_{\mathrm {c}}^{1.256} D \text { and } D_{\mathrm {D}}^{\perp } =0.39 P e_{\mathrm {c}}^{0.683} D\) are longitudinal and transverse dispersion coefficients, respectively [44]. The Peclet number is defined as Pec = |vdl|df/D, where df = 7μm is the fiber diameter.

From the Castro-Macosko [23] model, we obtain the viscosity as a function of the temperature and degree of cure,

where \(\mu _{\infty }\) is the viscosity at zero cure and \(T=\infty \), Eμ is the activation energy, cg is the degree of cure at gelation, and a and b are the parameters fitted from the dynamic and isothermal rheology tests.

Energy equation

We formulate the heat transfer equation considering the multi-phase flow and the deformable preform as (see Appendix A for detailed derivations)

where the homogenized specific heat \(\hat {c}_{\mathrm {p}} = n^{s}\rho ^{s} {c}_{\mathrm {p}}^{s} + n^{f}\rho ^{f} {c}_{\mathrm {p}}^{f}\). If the preform is fixed, the preform velocity turns to zero, vs = 0. Therefore, Eq. 21 reduces to

where T is the temperature, ΔH is the reaction heat of resin, and c denotes the resin degree of cure. kf and ks are the conductivity of the fluid and preform, respectively. \({c}_{\mathrm {p}}^{f}\) and \(c_{\mathrm {p}}^{s}\) are the specific heats of the fluid and fiber, respectively.

Equations 21 and 16 are the complete form of the infusion stage. The convection terms in those equations vanish during the curing stage since the velocities vdf and vdl are zero.

Numerical simulation

Figure 1 shows the setup of the numerical simulation. The carbon NCF preform is 350 mm in length, 70 mm in width, and 6.5 mm thick. The thermoset resin inlet and outlet are marked by the red and blue lines, respectively. The black edges are impermeable and perfectly insulated, and the green centerline is selected to collect and represent results. Because of the symmetry, we only model half of the preform.

Equations 4, 5, 21, 16 and 20 form a coupled initial-boundary value problem system. The system is decoupled by a staggered approach (shown in Fig. 2). In each time step, Eq. 4 is first solved for the degree of saturation. The updated degree of saturation is then used to solve the pressure from Eq. 5. Next, Eq. 21 is capable of updating the temperature, and the degree of cure is solved from Eq. 16. Finally, the viscosity is computed from Eq. 20. Upon the end of the infusion stage, the curing process is solved without (4) and (5).

Equations 4, 5, 21 and 16 are solved by the Galerkin finite element method and stabilized by the streamline upwind Petrov–Galerkin method [3, 45], when necessary. The backward Euler method is used for the time integration. The initial and boundary values are set as follows

-

ξ =0ξ = ξ(x,0) = 1 × 10− 6 as initial degree of saturation,

-

ξ = ξ0 = 1.0 at the inlet, and ∂xξ = 0 at the outlet;

-

p =0p = p(x,0) = 32mbar as initial pressure,

-

p = p0 = 1atm at the inlet, and p = p1 = 32mbar at the outlet;

-

T =0T = T(x,0) as initial temperature,

-

\(T=T_{0}={}^{0}{}{T}\) at the inlet, and \(T=T_{1}={}^{0}{}{T}\) at the outlet;

-

c =0c = c(x,0) = 0 as initial degree of cure,

-

c = c0 = 0 at the inlet, and ∂xc = 0 at the outlet.

We discretize the preform to a number of four-node bilinear elements. Different numbers of elements and time step sizes are chosen to study the convergence in “Results and discussion”. Tables 1, 2 and 3 list the parameters used in the simulation. Specifically, the parameters of the NCF fiber preform are obtained from the experiment in [9]. The parameters of cure kinetics and rheology of the thermoset resin are obtained from [33] and [46]. The temperature dependent heat conductivity and specific heat capacity of fiber and resin are obtained from [32]. The in-house code is developed in C with the Intel®; MKL PARDISO library and OpenMP®; library. The meshes are generated in Abaqus CAE, and the post processing is done by ParaView. We also remark that in the present development of the code distribution media has not been implemented.

Results and discussion

Convergence study

To study the convergence of the spatial and temporal discretizations, we employ five mesh schemes, which are mesh-1: 1000 elements, mesh-2: 2250 elements, mesh-3: 4000 elements, mesh-4: 6250 elements, and mesh-5: 9000 elements. Accordingly, we select five different time-step sizes, which are 1 × 10− 1 seconds (size-1) , 5 × 10− 2 seconds (size-2), 1 × 10− 2 seconds (size-3), 5 × 10− 3 seconds (size-4), and 1 × 10− 3 seconds (size-5). The studies are carried out when the initial temperature equals to 373 K and the infusion lasts 70 seconds.

The mesh size convergence study is based on the difference of state variables between mesh schemes 1 to 4 and the scheme 5, when the time step size is fixed at size-5. The error concerning the spatial discretization emRMS is defined as the root-mean-square (RMS) error as,

where NT is the total number of time steps; χmesh−i,t denotes the variable of the i-th mesh scheme at the t-th second. Once emRMSs are computed, the normalized error em is computed as

In Eq. 23, χ is computed as the integration of the variables over the whole preform as

where ϖ stands for the variable of temperature T, degree of cure c, viscosity μ, saturation degree ξ, and fluid pressure p in turns, B is the domain of the preform.

Similarly, the RMS error of time step size, etRMS, is defined as

where NNO equals to the total node numbers of the mesh scheme 5. ςsize−n,i represents the value of temperature T, degree of cure c, viscosity μ, saturation degree ξ, and fluid pressure p at the i-th node of n-th time step size. The normalized error et is computed as

Figure 3 shows that the fastest decrease in error happens when the element number changes from 1000 to 2250. As the element numbers increase, the error continues to reduce; however, the rate of change of error reduction becomes smaller and smaller. Thus, we choose the 6250 elements as the mesh scheme in this study since the error is lower than 10%.

The result of the convergence study of the time step size is depicted in Fig. 4. The error reduces faster when denser time steps are utilized, nevertheless the total error reduction is about 1%. That means that the smaller time step size will not contribute very much to the error control. Because of this, the 0.01 seconds is chosen as the time step size to save computational effort while still keeping good accuracy.

Process simulation

The exothermic infusion process highly depends on the ambient temperature. To study the effects of the initial temperature, we design five different cases. The initial temperatures, 0T, start from 298 K, end at 398 K, and we select the temperature every 25 K in between. Figure 5 shows the filling time and the maximum degree of cure for each given initial temperature. When the initial temperature varies from 298 K to 373 K, the filling out time drops 68.5%. On the contrary, the degree of cure increase three times. In this regard, the infusion process is accelerated by increasing the initial temperature. However, when the initial temperature keeps rising to 398 K, the resin gels at around 39 seconds. At this moment, the thermoset resin can not move forward anymore, and the process stops finally. However, if we consider the reactive thermoplastic resin instead of conventional thermoset resin, e.g., reactive methyl-methacrylate [36], the in-situ polymerized resin can be melted and flow again due to the heat from exothermic chemical reactions. In this regard, we find out that the resin flow through the whole preform much longer than the other temperatures. It takes about 278 seconds to fill out the preform with a very high degree of cure (0.839) at the end, as the semitransparent parts shown in Fig. 5. However, this theoretical hypothesis of the active thermoplastic resin need further experimental validation as a future work. In conclusion, there is a window of the processing temperature that can shorten the time of the infusion stage. If the initial temperature is too low, the effect of the accelerating process is small; however, if the temperature is too high, the resin gels before it flows through the whole preform. Nevertheless, regarding the advanced reactive thermoplastic resin, the total infusion time is unacceptable.

Figure 6 shows the flow front positions during the process at different initial temperatures. When the temperature varies from 298 K to 373 K, curves exhibit similar shape. The higher temperature gives a higher tangent of the curve, i.e., the flow front moves faster. Apart from that, at 398 K, the flow front moves fastest at the beginning, and it significantly slows down after 35 seconds until the resin flow stops at around 39 seconds. This is because the high initial temperature results in a faster curing process and the gelation of resin lead the viscosity to increase significantly. As mentioned before, the stopped resin can flow again under the heating from the chemical reactions of the reactive thermoplastic resin. The dashed line in Fig. 6 indicates the flow front positions of the reactive thermoplastic resin. It is obvious to notice the “elbow” shape at around 39 seconds, which implies the dramatic decreasing of the infusion speed after the polymerization starts.

In the VARTM process, a fundamental problem is the preform deformation. As reported in [9], the relaxation and lubrication mechanisms dominate the fiber preform deformation modes. Figure 7 shows the preform deformation along the centerline when the initial temperature equals to 373 K. The regions nearby the inlet have the largest thickness. Due to the lubrication mechanism, the minimum thickness parts locate around the flow front, and the widths of them overlap the partially-saturated regions. Upon the end of the infusion stage, the initial flatted preform turns into the shape of a wedge.

To study the development of the flow front in the course of the VARTM process, we plot the changes in temperature throughout the filling stage in Fig. 8a. The changes of flow front temperatures are limited small except the case of 398 K. The dashed line shows the rising of the flow front temperature due to the reactions of the reactive thermoplastic resin. The dashed line tells that the rate of change of the temperature changes from high to low at around 130 seconds since the amount of polymer that can be reacted reduces. When the whole preform is filled out, the jump of temperature is about 43 K. This large jump of the temperature accelerates the curing process and slows down the infusion process. Furthermore, the temperature profile of the case 0T = 373 K along the centerline is shown in Fig. 8b. During the process, the temperature profiles show the shape of an upside-down parabola at all four times. What is more, the maximum temperature at a specific time locates in the middle of the length of the filled-out path. This behavior reveals the heat conduction between the flow front and the dry fiber preform and the heat convection due to the moving resin/air-fluid in the wetted region.

Similarly, the flow front degree of cure and the profile of degree of cure along the centerline are plotted in Fig. 9. From Fig. 9a, we can notice that the flow front degree of cure develops linearly when the initial temperature is low (298 K, 323 K, and 348 K). When the initial temperature locates at a middle range (373 K), the degree of cure development represents non-linear behavior. At a high initial temperature, e.g., 398 K, the fully non-linear curing process is exhibited as the dashed line shows. By the control of the initial temperature, we can find a suitable process window of the temperate to reduce the cycle time and limit the resin polymerization. On the other hand, for a given initial temperature, 0T = 373 K, the profile of the centerline degree of cure is shown in Fig. 9b. The highest degree of cure occurs at the fully saturated flow front. The curves of the degree of cure represent the “cliff” shape fronts. Ideally, if it is the fully saturated case, the “cliff” will be straight and upright. However, the existence of the partially-saturated flow front in this study makes the steep slop “cliff” observed instead.

Last but not least, the curves of viscosity at the flow front and along the centerline are shown in Fig. 10a and b, respectively. The flow front resin viscosity shows similar linear and non-linear behaviors like Fig. 9a The viscosity increases to the peak very fast when the initial temperature equals to 398 K. The time matches with the “elbon point on the purple line shown in Fig. 6.

Just because of this high viscosity, the flow moves hardly forward in case of the thermoset resin. After this time, the temperature keeps rising due to the exothermic reactions, and the viscosity starts reducing for a long time, if the reactive thermoplastic resin is chosen. As the resin fills out the mold, the cure accelerates and leads the viscosity to increase again as the dashed line shows. Figure 10b is similar to Fig. 9b, but the curve at 70 seconds changes from the convex to concave. Then position of the change point corresponds with the peak temperature location in Fig. 8b. The reduction of temperatures gives rise the slower resin polymerization and viscosity rise.

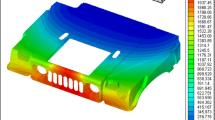

Next, we plot the contour plots from the 2-D simulation in Fig. 11. From Fig. 11a, we can see the temperature at the center of the width is lower than the edges. Furthermore, the differences in the temperature between the center and edges in the width direction are more extensive in the top half part, but very small in the lower half part, where is far away from the inlet. This pattern also shows in Fig. 11b regarding the degree of cure. Moreover, the lower part in Fig. 11bis almost in the same color, i.e., the resin is stacked at the same degree of cure in those regions. The color gradients only exist in the top half part, which means that the rate of change of the degree of cure is higher close to the inlet and lower when it is far from the inlet.

Conclusion

In this study, the coupled resin infusion and curing stages are modeled for the non-isothermal reactive VARTM process. Restriction is made to thin-walled fiber-reinforced polymer composite components, which significantly reduces the problem size. The implementation is thus made based on the shell model [8], extended by heat transfer, cure kinetics, and rheological models to investigate the effects of the exothermic polymerization during the VARTM process. In this development, two-phase porous media is used to model the in-plane resin infusion flow. For the flow front, the capillary effect combined with the relative permeability concept were considered to describe the competition between the resin and remaining air inside the fiber preform. In this context, heat transfer and cure kinetics equations are extended to consider the fiber preform deformation. When the highly convective non-isothermal flow of the reactive resin migrates into the preform, the resin curing generates heat that accelerates the process of polymerization. Accordingly, the resin viscosity and the flow velocity increase or decrease depending on the temperature and the degree of cure. On the other hand, the compaction and extension of the preform change the structure and permeability of the preform, which affects the infusion speed. In order to handle the coupled problem, a FE-based staggered solution procedure is considered. The corresponding convergence studies are also carried out.

By applying the VARTM process in different environmental temperatures, we discovered the existence of a temperature window, allowing for the infusion process speed up via the proper temperature control. When the temperature is too low, the infusion stage cannot speed up too much; however, when the temperature is too high, the process is facing stagnation due to gelation. As to the type of resin, emerging reactive thermoplastic resin with low viscosity at room temperature can replace the traditional thermoset resins in the RTM and VARTM processes. If we do so, based on the characteristics of thermoplastic resins, the partially polymerized resin can melt due to heating from chemical reactions. However, even though the process can continue, the infusion process slows down due to the high viscosity. With the aid of the presented framework, we can optimize the process parameters and the design of the mold, such as the initial temperature, the vacuum level, the position of the inlet and outlet. What is more, the proposed method can check the compatibility of a resin system for a given infusion task without relying on the experience and the “trial and erron approach.

References

Advani SG, Hsiao K-T (2012) Manufacturing Techniques for Polymer Matrix Composites (PMCs). Elsevier Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Hsiao K-T, Mathur R, Advani SG, Gillespie JW, Fink BK (2000) A closed form solution for flow during the vacuum assisted resin transfer molding process. J Manuf Sci Eng 122(3):463. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1285907

Wu D, Larsson R (2018) Homogenized free surface flow in porous media for wet-out processing. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 1(17). https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.5812

Simacek P, Advani SG (2003) A numerical model to predict fiber tow saturation during liquid composite molding. Compos Sci Technol 63(12):1725–1736. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-3538(03)00155-6

Zhou F, Alms J, Advani SG (2008) A closed form solution for flow in dual scale fibrous porous media under constant injection pressure conditions. Compos Sci Technol 68(3):699–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.09.010

Loudad R, Saouab A, Beauchene P, Agogue R, Desjoyeaux B (2017) Numerical modeling of vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding using multilayer approach. J Compos Mater 51(24):3441–3452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998316687145

Chevalier L, Bruchon J, Moulin N, Liotier P-J, Drapier S (2018) Accounting for local capillary effects in two-phase flows with relaxed surface tension formulation in enriched finite elements. Compt Rend Mécan 346(8):617–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crme.2018.06.008

Wu D, Larsson R (2019) A shell model for resin flow and preform deformation in thin-walled composite manufacturing processes. Int J Mater Form. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-019-01517-z

Wu D, Larsson R, Rouhi MS (2019) Modeling and experimental validation of the VARTM process for thin-Walled preforms. Polymers 11(12):2003. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11122003

Kamal MR, Sourour S (1973) Kinetics and thermal characterization of thermoset cure. Polym Eng Sci 13(1):59–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.760130110

Bogetti TA, Gillespie JW (1992) Process-Induced stress and deformation in thick-Section thermoset composite laminates. J Compos Mater 26(5):626–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/002199839202600502

Stanko M, Stommel M (2018) Kinetic prediction of fast curing polyurethane resins by model-Free isoconversional methods. Polymers 10(7):698. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10070698

Qi T, Pinter G, Antretter T, Krivec T, Fuchs P (2018) Model free kinetics coupled with finite element method for curing simulation of thermosetting epoxy resins. J Appl Polym Sci 135(27):46408. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.46408

Ruiz E, Trochu F (2005) Numerical analysis of cure temperature and internal stresses in thin and thick RTM parts. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 36(6):806–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2004.10.021

Muc A, Romanowicz P, Chwał M (2019) Description of the Resin Curing process—Formulation and Optimization. Polymers 11(1):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11010127

Benavente M, Marcin L, Courtois A, Lévesque M, Ruiz E (2018) Numerical analysis of viscoelastic process-induced residual distortions during manufacturing and post-curing. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 107:205–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2018.01.005

Maji P, Neogi S (2018) Development of kinetics sub-model of cyanate ester-based prepregs for autoclave molding process simulation. High Temper Mater Process 37(8):769–776. https://doi.org/10.1515/htmp-2017-0039

Dong A, Zhao Y, Zhao X, Yu Q (2018) Cure cycle optimization of rapidly cured out-Of-Autoclave composites. Materials 11(3):421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11030421

Garschke C, Parlevliet PP, Weimer C, Fox BL (2013) Cure kinetics and viscosity modelling of a high-performance epoxy resin film. Polym Test 32 (1):150–157. ISSN 0142-9418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymertesting.2012.09.011

Guo Z-S, Du S, Zhang B (2005) Temperature field of thick thermoset composite laminates during cure process. Compos Sci Technol 65(3):517–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2004.07.015

Hwang S-S, Park SY, Kwon G-C, Choi WJ (2018) Cure kinetics and viscosity modeling for the optimization of cure cycles in a vacuum-bag-only prepreg process. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 99 (9):2743–2753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-018-2467-y

Park SY, Choi CH, Choi WJ, Hwang SS (2019) A Comparison of the Properties of Carbon Fiber Epoxy Composites Produced by Non-autoclave with Vacuum Bag Only Prepreg and Autoclave Process. Appl Compos Mater 26(1):187–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10443-018-9688-y

Castro JM, Macosko CW (1982) Studies of mold filling and curing in the reaction injection molding process. AIChE J 28(2):250–260. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690280213

Henne M, Breyer C, Niedermeier M, Ermanni P (2004) A new kinetic and viscosity model for liquid composite molding simulations in an industrial environment. Polym Compos 25(3):255–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.20020

He W, He L, Ma Z, Yanlia G (2016) The kinetic and viscosity analysis of glycidyl azide polymer spherical propellant. J Therm Anal Calorim 124(2):943–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-015-5225-5

Li H, Zhang B (2016) Improved models of viscosity and relaxation modulus for epoxy resin during cure. Polym Eng Sci 56(6):617–621. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.24286

Zhang T, Zhao Y, Zhang B (2018) A method based on the time–temperature superposition principle to predict pressurization time in compression molding. J Appl Polym Sci 135(36):46664. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.46664

Karkanas PI, Partridge IV (2000) Cure modeling and monitoring of epoxy/amine resin systems. II. Network formation and chemoviscosity modeling. J Appl Polym Sci 77(10):2178–2188. https://doi.org/10.1002/10.1002/1097-4628(20000906)77:10<2178::AID-APP11>3.0.CO;2-0

Raghu K, Pandiyan R, Neogi S (2012) Viscosity modeling of a medium reactive unsaturated polyester resin used for liquid composite molding process. J Appl Polym Sci 125(2):1400–1408. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.35447

Geissberger R, Maldonado J, Bahamonde N, Keller A, Dransfeld C, Masania K (2017) Rheological modelling of thermoset composite processing. Compos Part B Eng 124:182–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.05.040

Celle P, Drapier S, Bergheau J-M (2008) Numerical modelling of liquid infusion into fibrous media undergoing compaction. Eur J Mech- A/Solids 27(4):647–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechsol.2007.11.002

Keller A, Dransfeld C, Masania K (November 2018) Flow and heat transfer during compression resin transfer moulding of highly reactive epoxies. Compos Part B Eng 153:167–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.07.041

Shi F, Dong X (2011) 3d numerical simulation of filling and curing processes in non-isothermal RTM process cycle. Finite Elem Anal Des 47(7):764–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.finel.2011.02.007

Grujicic M, Chittajallu KM, Walsh Shawn (2005) Non-isothermal preform infiltration during the vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding (VARTM) process. Appl Surf Sci 245(1):51–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2004.09.123

Ma L, Athreya SR, Mehta R, Barpanda D, Shafi A (2017) Numerical modeling and experimental validation of nonisothermal resin infusion and cure processes in large composites. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731684417691673

Fredi G, Dorigato A, Pegoretti A Novel reactive thermoplastic resin as a matrix for laminates containing phase change microcapsules 40(9):3711–3724. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.25233

Rudd CD, Long AC, Kendall KN, Mangin C (1997) Liquid Moulding Technologies: Resin Transfer Moulding, Structural Reaction Injection Moulding and Related Processing Techniques. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-84569-544-6

Burdine NT (1953) Relative permeability calculations from pore size distribution data. J Pet Technol 5(03):71–78. https://doi.org/10.2118/225-G

Brooks RH, Corey AT (1964) Hydraulic properties of porous media and their relation to drainage design. Trans ASAE 7(1):0026–0028. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.40684

Toll S (1998) Packing mechanics of fiber reinforcements. Polym Eng Sci 38(8):1337–1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.10304

Tucker CL, Dessenberger RB (1994) Govening equations for flow and heat transfer in stationary fiber beds. In: S.G. Advani (ed) Flow and rheology in polymer composites manufacturing. Elsevier, Science B.V, Amsterdam, p 257

Tan H, Pillai KM (2010) Numerical simulation of reactive flow in liquid composite molding using flux-corrected transport (FCT) based finite element/control volume (FE/CV) method. Int J Heat Mass Transfer 53 (9):2256–2271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2009.12.003

Staffan Lundström T (1997) Measurement of void collapse during resin transfer moulding. Compos Part A: Appl Sci Manuf 28(3):201–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-835X(96)00109-1

Han N-W, Bhakta J, Carbonell RG (1985) Longitudinal and lateral dispersion in packed beds: Effect of column length and particle size distribution. AIChE J 31(2):277–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690310215

Donea J, Huerta A (2003) Finite element methods for flow problems. Wiley, New York

Lin R, Lee LJ, Liou M (1991) Non-isothermal mold filling and curing simulation in thin cavities with preplaced fiber mats. Int Polym Process 6(4):356–369

Advani SG, Murat Sozer E (2010) Process modeling in composites manufacturing. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge partial suppo rt by Swedish Research Council Grant 621-2013-3907 and Chalmers University Area of Advance: Production. The simulations were performed on resources provided by the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC) at Chalmers Center for Computational Science and Engineering (C3SE).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Chalmers University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A:: Appendix A: Derivations of Eqs. 16 and 22

The balance relation of the resin chemical reaction can be expressed as

From [47], the energy balance for the fluid can be expressed without viscous dissipation as

Similarly, for the fiber preform,

Combining Eqs. 30 and 29 we obtain,

Appendix B: Materials data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, D., Larsson, R. & Blinzler, B. A preform deformation and resin flow coupled model including the cure kinetics and chemo-rheology for the VARTM process. Int J Mater Form 14, 421–434 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-020-01570-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-020-01570-z