Abstract

Wellbore drilling operations frequently entail the combination of a wide range of variables. This is underpinned by the numerous factors that must be considered in order to ensure safety and productivity. The heterogeneity and sometimes unpredictable behaviour of underground systems increases the sensitivity of drilling activities. Quite often the operating parameters are set to certify effective and efficient working processes. However, failings in the management of drilling and operating conditions sometimes result in catastrophes such as well collapse or fluid loss. This study investigates the hypothesis that optimising drilling parameters, for instance mud pressure, is crucial if the margin of safe operating conditions is to be properly defined. This was conducted via two main stages: first a deterministic analysis—where the operating conditions are predicted by conventional modelling procedures—and then a probabilistic analysis via stochastic simulations—where a window of optimised operation conditions can be obtained. The outcome of additional stochastic analyses can be used to improve results derived from deterministic models. The incorporation of stochastic techniques in the evaluation of wellbore instability indicates that margins of the safe mud weight window are adjustable and can be extended considerably beyond the limits of deterministic predictions. The safe mud window is influenced and hence can also be amended based on the degree of uncertainty and the permissible level of confidence. The refinement of results from deterministic analyses by additional stochastic simulations is vital if a more accurate and reliable representation of safe in situ and operating conditions is to be obtained during wellbore operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

An overview of experiences during the drilling and production of hydrocarbon from wells indicates rampant incidences arising from wellbore instability. The wellbore system becomes unstable when the integrity of the wellbore and surrounding formation can no longer hold or is threatened due to induced stresses or the weakening of the wellbore or formation materials. Wellbore instability poses a major problem during drilling, and its causes can be categorised into mechanical and chemical effects. Pašić et al. (2007) classify the factors contributing to wellbore instability as uncontrollable (natural) and controllable factors. Natural factors include the presence of naturally fractured or faulted formations, tectonically stressed formations, high in situ stresses, mobile formations, unconsolidated formations, naturally over-pressured rock collapse and induced over-pressure rock collapse; controllable factors include bottom-hole pressure (mud density), well inclination and azimuth, transient pore pressures, physicochemical rock–fluid interaction, drill string vibrations, erosion and temperature. Other factors which affect wellbore stability are the orientation of in situ stress fields, the mechanical properties of rock and bedding planes, and pore pressure (Chen et al. 1997).

The wellbore trajectory and mud density (also known as mud pressure) are amongst the factors which have a significant impact on the stability. Deviated wells have a greater tendency to become unstable (Standifird 2006) and can be measured in terms of the inclination and azimuth of wells with respect to the principal stresses. Wellbore failure happens when the tensile or shear strength of the formation and bedding plane is exceeded. To prevent this, the rock and bedding plane must be kept intact.

The mud density (mud pressure) is a dominant parameter that greatly influences the stability of wells, especially while drilling is being performed (Pašić et al. 2007). Pressure exerted by the drilling fluid (mud) instigates an additional concentration of stresses in the surroundings of the wellbore. Since the presence of effective stresses impacts on rock material behaviour, including failure, stability is highly dependent on the management of the mud pressure. The magnitude of mud pressure applied has to be adequate to avoid damage. Optimal values are usually in the high range; however, if the pressure is too high it may result in tensile fracturing and fluid loss, which are typical causes of instability. On the other hand, a mud pressure that is below the threshold (critical) value may not be sufficient in providing the necessary stress counterbalance to forestall collapse due to a preponderance of shear failure. The appropriate range of safe mud pressure is dependent on the local factors controlling individual cases and may differ for each scenario.

A classic example as illustrated in Mohiuddin et al. (2007) is the dependence of mud pressure on well inclination and azimuth. The susceptibility of deviated wells implies that they are more likely to fail if the same conditions used for vertical wells are applied. This is demonstrated in Mohiuddin et al. (2007), where comparisons of the mud density requirement between vertical, directional and horizontal wells are presented, indicating that generally greater magnitudes of mud densities are needed for non-vertical wells. It is inferred that horizontal wells require the highest range of values of mud densities. The derived critical mud pressure data and contour plots can be applied directly when designing wellbore alignment. Applications of this sort (the production and utilisation of critical mud pressure contour plots) are shown by Tan and Willoughby (1993) and Tan et al. (2004). Time dependency of the critical mud pressure is realised if there are temporal changes in controlling parameters such as rock material properties (e.g. cohesive strength). Chen et al. (2003a) showed a significant variation in critical mud weight when the shale cohesive strength changes with time.

Wellbore stability is also impacted by chemical interactions between drilling fluids (mud) and the host rock. Activities including ion exchanges and modifications in swelling pressure and rock water content are examples of chemical alterations; they occur when there is a disparity between the water activity in the rock and the water activity in mud (Chen et al. 2003a). Where the mud water activity is lower, the reduction in pore pressure and the corresponding increase in effective stresses increase stability (Chen et al. 2003a). In Ma and Chen (2015), a collapse pressure wellbore stability model for shale reservoirs was developed based on the analytical solution of stress induced by mechanical, hydraulic and chemical effects. The model is proposed for the assessment of the collapse pressure of shale reservoirs, and unlike conventional models, it shows the occurrence of failure regions not only at the borehole surface, but also at the interior of the formation. They demonstrate that rock strength parameters decrease with exposure to drilling mud, and in the formation, pore pressure increases while solute concentration decreases when the solute concentration of the drilling mud is less than that of the fluid in the pore space. A decrease in rock strength and an increase in pore pressure impact on wellbore stability in shale reservoirs. As illustrated by van Oort (2003), fluid–rock interaction can be managed so as to improve well stability or prevent instability.

The effect of temperature on wellbore stability can be observed when there is thermal diffusion within the formation. An increase in the formation temperature through the application of hotter drilling fluids adds to the pore pressure, thereby increasing the risk of instability (Chen et al. 2003a). In hydrate-bearing sediments (HBS), an increase in temperature has been shown in Freij-Ayoub et al. (2007) to speed up the dissociation of hydrates, causing corresponding reductions in cohesion.

The risk of instability is influenced by fractured reservoir formations. Fractured rock masses are embedded with natural discontinuities comprising bedding planes and fractures, which affect their homogeneity and overall physical and mechanical properties. Hence, apart from the failure of the intact rock, wellbore instability may be instigated at the planes of natural discontinuities. Chen et al. (2003b), Chen and Tan (2001) and Zhang et al. (1999) studied the effect of fractured rock masses on wellbore behaviour. It was ascertained that the probability of instability due to high differential stresses was considerably increased by the presence of fractures. Fracture patterns have variable effects due to differences in spacing, size, alignment, connectivity and strength property. Mud infiltration into fractures reduces their friction angle, causing a significant increase in the tendency for instability (Chen and Tan 2001; Chen et al. 2003b). Instability in fractured rock masses are mainly initiated along planes of discontinuity.

Uncertainty is inherent in wellbore design and drilling. Within a wider context it is generally split into two or three categories: aleatory uncertainties, epistemic uncertainties, and errors (Bulleit 2008; Chalupnik et al. 2009). Whereas aleatory uncertainties occur from randomness or contingency, epistemic uncertainties arise due to deficiencies in human knowledge. According to Bulleit (2008), sources of uncertainty include time, statistical limits, model limits, randomness and human error. Our focus is on uncertainties principally caused by randomness in material properties and underground conditions. This can be caused by inherent inconsistencies and unclear information due to limitations in test data (Savoia 2012). Parameters affecting wellbore stability consist of rock strength, magnitude and orientation of principal stresses, well orientation, pore pressure and mud pressure (Moos et al. 2003). The variability of these parameters implies a great deal of uncertainty during wellbore design, drilling and operation. While the other parameters are often uncontrollable, mud pressure (also referred to as mud density or mud weight) is an operational measure necessary to maintain stability.

Because we have limited our wellbore design and analysis in this study to a single vertical well, the magnitude and orientation of principal stresses, pore pressure and well orientation are assumed to be consistent at a given depth. Hence, the variability in the rock formation will be viewed as changes in rock material strength and deformation properties; amongst these, the Poisson ratio is considered the most unpredictable and as such also chosen as one of the variables to be stochastically modelled.

The pattern describing the uncertainties of design variables are probability distributions that can be assigned based on the trends of statistical dispersions including Gaussian normal, log-normal, Bernoulli sequence and Poisson distributions. The uncertainty in material properties can thus be designated according to prescribed probability density functions. Although a deterministic approach can be employed to define the safe mud pressure by observing the stress responses, there are some inherent limitations, so it does not account for all the uncertainties mentioned above. This research aims at carrying out follow-up stochastic analyses to investigate the robustness of wellbore conditions and design and to test the reliability of results from preceding deterministic analyses.

1.1 Review of wellbore stability studies

Some probabilistic-based approaches have been adopted in studies of wellbore stability. One of such methods is quantitative risk assessment (QRA) (e.g. Ottesen et al. 1999; McLellan and Hawkes 1998), which was employed by Moos et al. (2003) to determine the effect of uncertainties in input parameters (rock and reservoir properties) on well stability and optimal mud weight windows. Ottesen et al. (1999) had earlier introduced a QRA-based statistical technique—specifically for wellbore stability analyses—to measure uncertainties in input data and the probabilities of their effect in relation to mud pressures. An approach akin to this was applied by McLellan and Hawkes (1998) in modelling sand production. The input parameters used in Moos et al. (2003) are uniaxial compressive strength (UCS), pore pressure and in situ principal stresses (the vertical and two horizontal components). The response surfaces, typifying the wellbore behaviour, were calculated as quadratic polynomial functions of each input parameter. Monte Carlo simulations were used to compute uncertainties in wellbore collapse and lost circulation pressures. Quantitative risk assessment, based on the Monte Carlo method, was also applied by Moos et al. (2003) to assess uncertainties in seismic velocities and velocity transforms (velocity-density functions and velocity-effective stress functions), as they impact estimations of density, effective stresses and pore pressure. This information can be applied in determining the sealing pressure of rocks (reservoir), the mud pressure window, and the required number of drilling casings. This method of probabilistic technique often requires an extensive and densely populated sample size.

Latter studies (Al-Ajmi and Al-Harthy 2010; Al-Khayari et al. 2016; Niño 2016; Sheng et al. 2006) have included some aspects of sensitivity analyses using, for instance, the one-at-a-time (OAT) technique, to identify critical parameters. To quantify uncertainties in input data (rock properties), Niño (2016) applied four approaches: expert judgement; spatial variability; indirect measurement [a procedure borrowed from Holzberg (2001)]; and inconsistency of data sources, using Monte Carlo simulation. Monte Carlo simulation was applied in the model output uncertainty analyses and used to derive safe mud windows based on probability estimates. Sensitivity analyses were also completed using both the one-at-a-time (OAT) method and the response surface methodology (RSM). The maximum horizontal stress and cohesion were key to determining collapse pressure, since they had the most influence, while the maximum and minimum stresses played a similar role in estimating the fracture pressure. The Poisson ratio and vertical stress were perceived to have trivial effects on responses. Similarly, critical mud pressures have been estimated through probabilistic wellbore stability analysis where Monte Carlo sampling techniques were used to capture uncertainties in in situ stresses, wellbore trajectory, cohesion, friction angle, Poisson ratio (Al-Ajmi and Al-Harthy 2010; Al-Khayari et al. 2016; Sheng et al. 2006), pore water pressure and rock strength (Sheng et al. 2006). Wellbore trajectory was determined as the most influential parameter causing wellbore collapse (Al-Khayari et al. 2016), while other critical parameters impacting on wellbore stability were identified as friction angle, cohesion and maximum horizontal stress (Al-Ajmi and Al-Harthy 2010). Comparisons between Mogi–Coulomb and Mohr–Coulomb failure criteria indicate that the former produces greater (conservative) magnitudes of minimum overbalance pressures (Al-Ajmi and Al-Harthy 2010).

In addition, deterministic wellbore stability models have been developed for the following purposes: to define safe mud pressure windows (Aslannezhad et al. 2016); for wellbore stability assessments which allow correlations through the use of limited available input data to derive others such as in situ stresses and some rock mechanical properties (Simangunsong et al. 2006); for well path optimisation (Ma et al. 2015); and to compare the outputs of failure models such as Mogi–Coulomb and Mohr–Coulomb failure criteria (Aslannezhad et al. 2016; Ma et al. 2015), and Mohr–Coulomb, Drucker–Prager and modified Lade failure criteria (Simangunsong et al. 2006). For instance, Ma et al. (2015) derived a semi-analytical model for wellbore stability analysis from the analytical solution of stress distribution around a borehole, rock failure criteria and a breakout width model. This model was used to compare the performance between Mohr–Coulomb and Mogi–Coulomb failure criteria, to calculate the mud weight extrema and to establish the most stable well path. The Mohr–Coulomb criterion is shown to be more conservative than the Mogi–Coulomb criterion, and contrary to conventional methods, the optimal stable well path using this method is shown to be vertical for normal faulting (NF), normal to strike-slip faulting (NF-SS) and strike-slip faulting (SS) stress regimes.

1.2 Focus of study

To address the high variability in underground conditions, stochastic methods are being used to reflect the temporal and spatial changes during drilling and operations. The uncertainty is applicable to a wide range of parameters comprising pore pressure, uniaxial compressive strength (UCS), in situ stresses, Poisson ratio, void ratio, tensile strength, angle of internal friction, cohesion, elastic modulus, etc. Hitherto, elastic modulus, Poisson ratio and void ratio are parameters that are largely omitted in wellbore stability investigations. A plausible reason for the non-inclusion of void ratio is that direct measurements and data are not readily available, especially within subsurface environments. Furthermore, the Monte Carlo-based probabilistic techniques commonly employed often require an extensive and densely populated sample size.

Consequently, this study considers the ramifications of uncertainties in void ratio, Poisson ratio and elastic modulus. These are sensitive properties with significant corollaries that reflect in the trend of other properties. The elastic modulus is a function of the compressive strength and strain of the rock. It is a deformation parameter as it determines the extent of material distortion for given imposed stress conditions. The void ratio is a measure of consistency and packing of the rock grains and has several ramifications through, for example, estimates of porosity, specific gravity, density and saturation. The Poisson ratio defines the attributes of alterations in the morphology of the rock under imposed stress conditions. The relationships between the elastic, bulk and shear moduli are readily quantifiable where appropriate estimates of the Poisson ratio and its uncertainties are available. In place of quadratic polynomial functions, the response surface in this study is characterised explicitly by a finite element geo-mechanical wellbore model. A linkage allows the exchange of information between the finite element wellbore model and the stochastic model. Traditional Monte Carlo simulations are also replaced by quasi-Monte Carlo simulations which circumvent the need for large samples.

To further the understanding of wellbore stability and the probabilistic delineation of safe mud pressure windows this study serves to

-

create a platform that engenders quantitative comparisons of outputs between deterministic and stochastic predictions of safe mud windows,

-

demonstrate the performance of quasi-Monte Carlo integration/sampling as a suitable method of achieving low discrepancies and decreased clustering during selection,

-

apply concurrent alterations of input variables during sampling (each selected from a repository of Gaussian distributed values),

-

illustrate the potential of a procedure that integrates deterministic and stochastic numerical models to obtain synchronised and optimised solutions, and

-

present the distinct combination of Poisson ratio, elastic modulus and void ratio as characteristic input rock properties.

2 Numerical procedure

Deterministic methods aimed at ascertaining the impact of design parameters on the overall behaviour of systems are often saddled with underlying assumptions that simplify the randomness in variability. Additional stochastic analysis ensures that, if the probabilistic distribution of design or input variables is accurately defined, the probabilistic distribution of output variables (e.g. stress and pressure) can be portrayed in a manner that more correctly describes the response of systems. An integrated process is adopted in this study entailing independent deterministic analyses, followed by stochastic analyses, which are conducted via interactive exchanges between a deterministic numerical model and a probabilistic numerical model to reach optimised solutions. Figure 1 shows how this approach may feed decision making.

Integrating structural analysis and optimisation (Howard 2007)

2.1 Domain description

The model domain and attendant conditions are modelled to represent wellbore drilling operations, comprising a single wellbore drilled in a multi-layered multi-property formation. Drilling of the wellbore is accompanied by string casing installations whereby segments of string casing pipes are placed as drilling continues towards the target zone. Development of stress during this phase is critical. The domain geometry and boundary conditions are built using the finite element software Abaqus, which was also used to conduct the deterministic analysis. Taking advantage of the domain symmetry, only a quarter of the section was simulated. A schematic showing the boundary conditions is given in Fig. 2 where the rock stratification depicts the different layers. A string casing segment of 183 m is considered and located at about 3000 m below sea level (Figs. 3, 4). Along this segment the horizontal principal stresses vary linearly with depth. The total horizontal stresses vary from 13.69 MPa at the top of the segment to 40.44 MPa at the bottom of the segment, while the effective horizontal stresses vary from 5.26 MPa at the top of the segment to 13.76 MPa at the bottom of the segment (Figs. 5, 6). These were determined based on the given subsurface geological conditions using relevant equations (Eqs. 1–13).

Adapted from Moos et al. (2003)

Longitudinal profile of the domain segment: lithology showing rock stratification of the formation segment (chert in green, sandstone in brown and shale in grey).

A cross section of rock layers consisting of sandstone strata sandwiched between layers of shale and chert is taken as the specific area to be investigated (Fig. 4), although the same analysis could be repeated at deeper or shallower depths. Table 1 shows the linear-elastic rock material properties.

Deep ocean drilling operations are typically carried out to extensive depths below the ocean floor. The average depth of oceans ranges from 1205 m for the Arctic Ocean to 3970 m for the Pacific Ocean with a maximum depth of up to 11,034 m recorded for the Challenger Deep located in the Pacific Ocean. Although the terms ocean and sea are often used interchangeably, a sea actually refers to that portion of an ocean that is partially enclosed by land and is shallower. For this model, a depth (2000 m) in between the lower and upper limits of average values is used. A rock depth of 1000 m below the ocean floor is selected as the top of the segment (Fig. 3). In essence, the top of the rock segment is considered to be 3000 m below sea level.

2.2 In situ and induced stresses

To account for the overburden pressure or vertical stress acting at the top plane of the segment of interest, loads accruing from the following were considered: the atmospheric pressure acting on the ocean surface; the hydrostatic pressure from the body of water constituting the ocean, which is assumed to be at static equilibrium or, more precisely, mechanical equilibrium; and the overburden effect due to the first 1000 m depth of rock layer directly beneath the ocean floor. Hence, the overburden pressure (stress) at the top of the segment is given by Eq. (1), adopted from the principle of stresses below water level, at the sea bed (Atkinson 2007).

where \(P_{\text{atm}}\) is the atmospheric pressure; \(\sigma_{{{\text{v}}({\text{water}})}}\) is the stress due to the weight of the ocean; \(\sigma_{{{\text{v}}({\text{rock}})}}\) is the vertical stress from the overlying rock layer; \(\rho_{\text{w}}\) is the density of water; \(g\) is the acceleration due to gravity; \(h_{\text{o}}\) is the ocean depth; \(\rho_{{{\text{b}}({\text{wet}})}}\) is the wet bulk density of the overlying 1000 m of rock; and \(h_{\text{r}}\) is the thickness of the overlying rock layer.

While vertical stresses are determined from rock densities integrated over cumulative depths from the surface to the position being considered, horizontal stresses can be measured from mini-fracture tests, step-down tests (injection/falloff tests), well log data and wellbore breakout analyses (Vernik and Zoback 1992). Alternatively, where values of the rock mechanical properties such as Poisson ratios and elastic moduli are accurately determined, relationships between in situ stresses can be established that enable the derivation of horizontal stresses from known values of the vertical stress. For a rock subjected to uniaxial compression, the total strain in the direction of loading, for instance, in any of the horizontal alignments, is given as

where \(\varepsilon_{\text{h}}\) is the horizontal strain; \(\sigma_{\text{H}}\) and \(\sigma_{\text{h}}\) are the maximum and minimum horizontal stresses, respectively; \(\sigma_{\text{v}}\) is the vertical stress; E is the elastic modulus; and \(\upsilon\) is the Poisson ratio. It is assumed that one of the horizontal strains is negligible (e.g. \(\varepsilon_{\text{h}} \approx 0\)) and the maximum and minimum horizontal stresses are equivalent (\(\sigma_{\text{h}} \approx \sigma_{\text{H}}\)); Eq. (2) is modified to

where

\(K\) is known as the coefficient of lateral earth pressure (ratio of horizontal to vertical stress). Under certain conditions, for instance, in normally consolidated soils at rest, \(K\) has been suggested to depend on the shearing resistance (\(\phi\)) (Jaky 1944; Radoslaw and Michalowski 2005), given as

This Eq. (4) was further adjusted to account for over-consolidated soils by incorporating an over-consolidation ratio (OCR), resulting in a modified \(K\) value (Mayne and Kulhawy 1982).

where \(\phi\) is the effective stress friction angle. In this study, we consider the depth and elastic modulus as influencing factors that significantly affect the stress regime. This is discussed in Sheorey et al. (2001) and Sheorey (1994), where it is demonstrated that in transverse isotropic conditions, the in situ horizontal stress is a function of not only the depth; it also depends on the elastic modulus measured in the horizontal direction since the elastic modulus in the horizontal orientation has a greater impact on the horizontal stress compared to other elastic properties. This dependency is primarily because of the geothermal gradient within the earth’s crust and mantle with the steepness of this ramp being much greater in the crust. The temperature gradient is shown to be considerably higher near the surface. In isotropic conditions, generalised expressions for the coefficient of lateral earth pressure and horizontal in situ stresses can be adopted (Sheorey et al. 2001), which presupposes that \(E_{\text{v}} = E_{\text{h}}\). K is thus given as (Sheorey 1994)

For Eq. (6), h is the depth of the cover, that is, the depth measured from the surface to the point of interest; K varies between 0.4 and 1.5 for depths below 1000 m (Eshiet and Sheng 2013). We have calculated our K values based on Eq. (6) since it produces more realistic estimates.

Pore pressure within a formation can be determined using data from acoustic and resistivity well logs whereby the sonic transient time and formation resistivity are measured against depth. A formation pore pressure can also be simply calculated from the hydrostatic pressure gradient which shows a linear increase in hydrostatic pressure with depth. However, this does not account for deviations from the normal trend line or the normal compaction trend due to disparities in rock properties, for instance, in areas of abnormal compaction, porosity and fluid movement. An over-pressure condition can be easily generated in locations of high density and decreased porosity. Whereas the sonic transient time decreases linearly with depth due to reduced porosity, resistivity is shown to increase nonlinearly with depth. This trend was established by Hottmann and Johnson (1965). The divergence of the measured sonic transient time and resistivity from those observed from normal compaction trends in hydrostatic conditions is used as an indicator of the abnormal fluid pressure in the area. This is based on the premise that deviations from the normal pore pressure in an area are caused by changes in the petrophysical properties such as porosity, density and fluid flow (Azadpour et al. 2015).

There are several methods of estimating pore-pressure-based empirical derivations and petrophysical properties, for example Eaton’s, Bower’s, and Miller’s compressibility and resistivity methods, and the Tau model (Azadpour et al. 2015; Zhang 2011). With an exception of the compressibility and resistivity methods which use the rock compressibility and resistivity, respectively, to calculate pore pressure, other techniques are based on compressional velocity and sonic transit time obtained from well logs. Eaton’s method is presently the most widely adopted technique and is based on empirical derivations using sonic transit times.

Our model composes three rock types (shale, sandstone and chert) in different layers spanning a 183-m segment (Fig. 4). The distribution and thickness of individual layers as well as the disparity in petrophysical properties such as porosity (13%–26%), void ratio (0.15–0.35) and bulk density (1880–2174 kg/m3) are not considered varied enough to warrant a non-trivial impact on the normal compaction trend and linear increase in hydrostatic pressure even though there are dissimilarities in material and properties. Fluid pressure is hence approximately represented by an incremental and linear increase in hydrostatic pressure with depth (Fig. 5). The assumption presupposes the dependency of pore pressure on the overburden stress and effective stresses. In other words, the overburden stress is balanced by the sum of the pore pressure and vertical effective stress. These fundamental relationships are presented in Biot (1941), Terzaghi (1943) and Terzaghi et al. (1996). The generalised form is

where S is the overburden stress; \(\acute{\sigma}_{\text{v}}\) is the effective vertical stress; \(\alpha\) is the Biot effective stress coefficient; and \(P_{\text{p}}\) is the pore pressure. Under hydrostatic conditions, the pore pressure is

The Biot effective stress coefficient defines the change in the bulk volume of a material as the pore pressure fluctuates and may be determined by means of several empirical relations. For rock, this coefficient generally increases with porosity and is shown to have values up to 0.9 for rock porosities of approximately 0.18 (Alam et al. 2010; Luo et al. 2015). With respect to this study, the formation being considered is predominantly sandstone with an average porosity of approximately 0.26. Hence, Biot’s effective stress coefficient with an estimated value of 1.0 is assumed.

By adopting Sheorey’s formulation (Eq. 6), we have assumed a vertically and transversely isotropic rock formation. This assumption is extended to the initial stress condition, which—for a simplified case—is also taken to be transversely isotropic implying insignificant disparities between the maximum and minimum horizontal stresses (\(\sigma_{\text{h}} \approx \sigma_{\text{H}}\)). While the vertical stress is computed from an integration of the weight of the overburden determined from the densities of water and the various rock types, the horizontal stresses are estimated using the horizontal-to-vertical stress ratio (Eq. 6) and are functions of the elastic modulus and depth. Profiles of the initial in situ stress distributions are shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

2.3 Formation rock properties

Porosity is the ratio of the volume of void space to the bulk volume of a material and is a measure of how much fluid can be contained within a volumetric space. It is a function of the material properties and decreases with depth due to increased compaction. It is also dependent on the fluid pressure at a given depth. This proportional relationship can be used to infer high porosity values in areas of abnormally high fluid pressures (Hottmann and Johnson 1965). Porosity values for rocks are wide ranging depending on a number of factors such as the formation and depth. For instance, average values for shale as low as 0.096 at deep depths (1833–1882 m) and as high as 0.335 for shallow depths (89–281 m) have been recorded for a formation in Eastern Venezuela formed during the Oligocene and Miocene periods (Manger 1963). Likewise, average sandstone values may be as low as 0.007 (for dolomitic sandstones at depths 3964–4013 m) to as high as 0.456 for outcrops (Manger 1963). The porosity of chert in some formations is shown to be within the range 0.01–0.06 for black chert and 0.21–0.40 for white chert (Shanmugam and Higgins 1988). The transformation, during which the rock is altered through a process of dissolution and weathering from black to white, increases its porosity. Black chert is much denser and less porous than white chert. From the segment profile (Fig. 4), sandstone is predominant, spanning about 60% of the vertical cross section. It is regarded as the main hydrocarbon-bearing rock type. To reflect this, an average initial porosity of \(\approx 0.26\) was assigned for sandstone, while shale and chert were given values of 0.15 and 0.13, respectively. With known values of porosity, the corresponding void ratios and wet and dry bulk densities are directly derived through the following standard expressions:

Alternatively, the porosity can be determined indirectly through the following relationship

where \(e\) is the void ratio; n is porosity; \(G_{\text{s}}\) is the specific gravity; \(\rho_{{{\text{b}}({\text{wet}})}}\) is the wet bulk density; \(\rho_{{{\text{b}}({\text{dry}})}}\) is the dry bulk density; and \(\rho_{\text{s}}\) is the particle (mass) density expressed as

Based on the range of typical values for specific gravity (e.g. 2.2–2.8 for sandstone and 2.4–2.8 for shale), 2.5 was taken to be a representative average. Mean values of other properties including Poisson ratio \(\upsilon\), elastic modulus \(E\), and permeability \(k\), are given in Table 1. The elastic modulus should generally increase with depth (Moayed and Bolandi 2012) which amongst other factors may be attributed to the increase in consolidation (Moayed et al. 2012); nevertheless, because of the short interval under consideration we have used consistent initial values for each rock type.

Pore pressure along the rock segment ranges from 29.7 MPa at 3000 m to 31.3 MPa at 3183 m, giving an average value of 30.4 MPa. Ideally to ensure equilibrium and to deter fluid flow into the wellbore, the applied mud pressure should, at least, match the maximum pore pressure within the reservoir. Once a well bore is drilled, a pore pressure gradient is naturally established with the lowest magnitude occurring at the wellbore. This phenomenon is essential for enabling fluid flow towards the well. Hence, mud pressure is used to control the pressure gradient and fluid flow. It is also used to maintain well stability by preventing well collapse due to excessive shear and compressive stresses at the periphery of drilled cavities. The magnitude of mud pressure applied is therefore subject to many factors. Excessive high mud pressure may lead to tensile failure and loss of fluid during circulation. On the other hand, insufficient mud pressures may instigate compressive failure and wellbore breakouts. Mud pressures that are too low may not be sufficient to prevent uncontrollable inward flow and well collapse. A pressure gradient was established by setting the pore pressure at the wellbore surface to 23.95 MPa in order to initiate fluid flow.

3 Modelling methodology

The mud pressure is the principal parameter to be investigated due to its role in well stability. The determination of a window that provides a safe range of mud pressures that can be applied without compromising the integrity of the wellbore during drilling is the underlying purpose of this work. This is accomplished in two main stages: deterministic and stochastic analyses.

3.1 Deterministic analysis

This method is used to define an initial range of safe mud pressures. The safe mud pressure window is restricted to the specific string casing length being considered, which implies that a repeated analysis should be performed for each successive interval of depth. Also, as previously mentioned, the deterministic method largely relies upon accurate measurements of the geo-mechanical conditions around the well and cannot account for uncertainties under this setting.

The deterministic analysis was conducted by finite element numerical method (using Abaqus 6.10) and the radial strain taken as the response parameter. A depth approximately 3000 m below sea level for an interval spanning 183 m was adopted as the target area. It is assumed that the magnitude of safe mud pressures increases progressively with depth. The mud pressure and radial strain were taken as input and output parameters, respectively. With these, a response curve is derived at the end of each set of simulations. The applied mud pressure was varied between 0 and 60 MPa, with each value plotted against the maximum radial strain at the onset of failure. Failure of wellbores occurs in two main modes: compressive and tensile. Compressive failure is attributed to wellbore breakouts which happen when the wellbore stress exceeds the rock compressive strength. This is often mitigated by increasing the mud pressure/weight to counterbalance and decrease the compressive stresses at the wellbore vicinity. Tensile failure occurs when the excessive mud pressure increases tensile stresses to magnitudes exceeding the rock tensile strength. An indication of tensile failure is the initiation and propagation of fractures. The magnitude of the maximum radial strain is, thus, matched against the corresponding exerted mud pressure, and the region where neither breakout/collapse, nor fracture occurs is delineated as the stable region. The compressive and tensile failure criterion is governed by the elastic theory of deformation of materials whereby failure is deemed to have occurred when the material yield strength is surpassed. The result is therefore conservative as the post-yield behaviour of the material is not considered.

3.2 Stochastic analysis

The stochastic analysis is carried out to verify the reliability of results from the deterministic study and where necessary redefine it for better accuracy. Additional variables are introduced that allow for risk assessment and optimisation of the results. Variability in the domain characteristics such as the rock material properties and behaviour presents uncertainties in resulting outputs. An iterative procedure ensures that various scenarios or combination of scenarios are accounted for. Repetitive calculations that entail the variation of different combinations of input parameters produce corresponding outcomes that depict the state of the wellbore for a given set of initial and boundary conditions. This heuristic approach is common in optimisation techniques, but is essential in determining required probability and cumulative density distributions.

Stochastic methods are statistical approaches for determining probabilities of specific outcomes. The main object of stochastic analysis as applied in this study was geared towards defining the safe mud pressure window under a given set of conditions. To achieve this it is mandatory to predict the probability of obtaining a predefined outcome for given mud pressures. The Monte Carlo sampling method remains the most widely used stochastic technique. The simple Monte Carlo method requires a large sample size resulting in greater computational cost. Hence, in its simple form, it may not be suitable where there are constraints in the extent of the sample domain and computational resources.

The stochastic analysis was performed using the optimisation software, HyperStudy, by linking it with the finite element solver. Thus, by altering the study set-up within the HyperStudy domain, the finite element solver is repeatedly fed different sets of input parameter values. For this work we focused on the spatially and temporally changing rock properties at the proximity of the wellbore. Amongst these properties Poisson’s ratio was identified as a parameter that may have greater inconsistency because of uncertainties in its estimation. The Poisson ratio plays a major role in rock deformation and impacts on stress distributions and, in general, wellbore stability. Whereas in the deterministic analysis only mud pressure is varied, for the stochastic study Poisson’s ratio, void ratio, elastic modulus (which are inputs representing the material property design variables) and mud pressure are altered in a manner predefined by an assigned statistical distribution pattern, in this case the normal distribution. HyperStudy generates samples through the Hammersley algorithm. A sample size of up to 200 was produced and each passed on to the finite element solver at every run.

Many variances of the Monte Carlo method which require much reduced sample sizes are available such as Latin hypercube sampling, orthogonal array sampling, adaptive importance sampling and generalised antithetic sampling. Quasi-Monte Carlo methods provide good or even better alternatives to random sampling methods (i.e. Monte Carlo sampling). These are also known as low-discrepancy sequences. Though quasi-Monte Carlo integration functions in a similar manner to Monte Carlo integration, it uses sequences of quasi-random numbers for the numerical integration. They reduce clustering during sampling, resulting in a wider spread, and also enable an accelerated convergence rate (Caflisch 1998). In order to take advantage of these features, Hammersley sampling (Hammersley and Hanscomb 1964), which is one of such methods, was employed in this study.

The domain of the design variables are characterised by a normal distribution, typically comprising mean values, standard deviations and variances. For stochastic analyses it was necessary, in some cases, to modify the variances to ensure the desired dispersion is maintained which should ideally spread between lower and upper bound values. These may sometimes require an amendment of the mean value.

The wellbore analysis was performed using a design exploration, study and optimisation software, HyperStudy 13.0. The physical model and solver was executed by a finite element software, Abaqus 6.14. The physical wellbore model was built with Abaqus, while all analyses, using Abaqus as the solver, were conducted with HyperStudy. The study was set up through the following sequential procedures: introducing and defining the parameterised file model; defining the design variables; specifying the mode of running the study set-up; evaluating and performing relevant tasks; defining the responses to be analysed; and post-processing the results. When the study has been set up, several analyses can be conducted. Depending on the object of the investigation, an unlimited number of combinations of study approaches can be employed (e.g. Fig. 7). Study approaches commonly used in practice comprise design of experiments (DOEs), fit, optimisation and stochastic analysis; however, in accordance with the delineation of this investigation, emphasis was placed on DOE and stochastic analysis.

Typical combinations of study approaches (Altair Engineering 2014)

3.2.1 Study set-up

3.2.1.1 Parameterised file model

The Solver input file created by Abaqus was parameterised to obtain a HyperStudy template file with an ASCII text format. Details of the model are included in template statements that enable the replacement of data fields with parameters. The use of parameters permits the automatic alteration of design variables within predefined bounds. The solver input-parameterised file precludes the need for importing the complete Abaqus model environment (.cae file).

3.2.1.2 Design variables

To define the design variables, the following were specified: the initial, lower bound and upper bound values, the data type, data continuity and distribution, and distribution properties. A continuous rather than a discrete dispersion of data was used, and the normal distribution was used to characterise the statistical scatter of each design variable.

3.2.1.3 Responses

Responses were defined with respect to the most important output variables required for observation. Usually, values of the output variables are subsequently fed into the main study approaches (e.g. DOEs and stochastic analyses).

3.2.2 Description of study approaches

Two interrelated but independent categories of analysis will suffice for this investigation: design of experiment (DOE) and stochastic analysis. The scope of this study is limited to stochastic analyses.

3.2.2.1 Design of experiment

DOE is a systematic way of establishing trends in the relationship between the factors that contribute to a process and the outcomes of the process (Fig. 8). In this cause-and-effect type of relationship, the input variables are examined to determine their impact on the response of the system in such a way that facilitates understanding of its global behaviour. This information is crucial if the input factors are to be manipulated to optimise the system output; it is also essential for abating the extent of exposure to risk. Input factors may be either controllable or uncontrollable. As the nomenclature implies uncontrollable factors are parameters that cannot be altered and so may either remain constant or are governed by remote conditions. On the other hand, controllable input factors can be modified to yield outcomes that are subjected to further scrutiny. DOE determines the extent of influence of input factors; the most influential input factors can be set such that the system response is close to the desired output and variation in the output as well as the brunt of uncontrollable input factors is minimised. DOE studies can also be used to construct surrogate models for computationally intensive solvers.

3.2.2.2 Design variables

One operation parameter and three controlled design parameters were selected as input variables: mud pressure, elastic modulus, Poisson ratio and void ratio. Mud pressure is a well operation parameter that represents the mud weight commonly applied to maintain well integrity during drilling and extraction process. It is also referred to as the bottom-hole pressure. The magnitude and gradient of this pressure must exceed the formation pressure gradient to avert the inflow of formation fluid to the wellbore and well breakout; however, excessive mud pressure increases the potential for tensile fracturing and fluid loss. The elastic modulus and Poisson ratio are deformation parameters that dominate control of the rock strain characteristics, particularly at the elastic range. The void ratio is a measure of consistency and packing of the rock grains and can be used to estimate porosity, specific gravity, density and saturation.

The proposed lower bound, upper bound and initial value of the input design parameters are given in Table 2. These are generated random variables that are continuous and characterised by normal statistical distributions typically skewed about the mean. The normal distribution was chosen since it approximates the occurrence of most natural phenomena. Its probability density function (PDF) is

where \(\sigma_{{\bar{x}}}\) is the standard deviation; \(\mu\) is the mean value of sample; and \(x\) is the value of the design variable.

3.2.2.3 Responses/output

The range of selected responses is usually required in assessing wellbore integrity either directly or indirectly. They are categorised under stress, strain and displacement with only the maximum and minimum values being recorded since the extrema values were solely required for the investigation. An exhaustive list of the response parameters is presented in Table 3.

The state of a wellbore can be checked by evaluating the stress, strain and deformation conditions. These can be applied in determining criteria for wellbore failure. Wellbore failure is often described in two modes: compressive and tensile failure (Sheng et al. 2006). Compressive failure happens where the compressive strength of the rock is exceeded by the wellbore stresses resulting in well breakout. Likewise, tensile failure occurs where the rock tensile strength is exceeded causing hydraulic fracturing and loss of circulation fluid. Because wellbore stability is directly dependent on the extent at which compressive or tensile deformation has occurred, it is more straightforward to adopt a strain or deformation criterion as a measure of the wellbore failure. For this study critical radial compressive and tensile strain values were used to ascertain the advent of rock failure and wellbore instability.

4 Results and discussion

It is imperative that wellbore instability be considered as an integral factor during drilling and other well operations. These instabilities are attributed to mechanical and/or chemical effects (Pašić et al. 2007). Mechanical effects may be caused by, for instance, lack of caution during drilling, excessive stresses around the wellbore or weak formation rock. On the other hand, chemical effects arise due to the often complex interactions between the formation rock, formation fluid and drilling fluids. The combined impact of both mechanical and chemical effects is frequently manifested in field conditions. The conventional approach to ensure that the rock surrounding the wellbore during drilling or production remains intact is by the radial application of mud pressure using fluids with specialised properties. Knowing the correct magnitude of mud pressure (also referred to as mud weight since the pressure is a function of its density) to exert is crucial in order not to instigate instabilities that may lead to wellbore failure. A deterministic approach can be used to mark the limits beyond which well failure would occur. Theses limits are defined in terms of the range of safe mud pressures, implying an upper and lower bound. The upper bound represents the highest mud pressure value. Pressures above this magnitude result in wellbore failure or jeopardise its stability. Similarly, the lower bound represents the lowest mud pressure value below which wellbore failure will occur. The actual window of safe mud pressure is case specific and highly dependent on the type of rock encountered in the reservoir, the drilling practice and fluid flow in the reservoir.

In several instances the lower bound is set as the minimum allowable mud pressure to counterbalance compressive stresses that lead to compressive/shear failure of the wellbore; this is referred to as well breakout. For permeable formations, the minimum allowable mud pressure should also prevent an inflow of the reservoir fluid. For this to be achieved, the minimum allowable mud pressure must be greater than the formation pore pressure. At the opposite end, the maximum allowable mud pressure is defined as the highest magnitude of mud weight that can be applied without causing tensile failure, loss in circulation or hydraulic fracturing of the formation (Hilgedick 2012; Moos et al. 2003). The above conditions are likely to apply where the pore pressure gradient is low or normal such that a considerably low mud pressure is sufficient to restrict the influx of reservoir fluids. A low or normal pore pressure gradient also invariably suggests that the pore fluid velocity at the vicinity of the wellbore face is low. If the pore pressure gradient is steep, the associated pore fluid velocity near the wellbore will be high. Sufficiently high pore pressures can generate effective tensile stresses causing tensile failure where the rock strength is exceeded. This has been observed by French et al. (2012) and Secor (1965), where natural hydraulic fractures and dilation are reported to occur when the pore pressure surpasses the least in situ compressive stress by a magnitude equivalent to the rock tensile strength. Dilation and fracture were also shown to take place in response to a high strain rate. Likewise, high pore fluid velocities create tensile stresses that may cause tensile failure if the rock tensile strength is exceeded. Where there is a decline in permeability or at very high flow rates, the increased drag forces cause the effective radial stresses to become negative, leading to tensile failure (Eshiet and Sheng 2013; Morita et al. 1998; Nouri et al. 2002).

Hence, the in situ pore pressure or pore pressure gradient influences the reservoir characteristics, especially near the wellbore region, and plays a dominant role in determining the regime of stresses generated. This weighty effect of the prevailing pore pressure condition implies that at high in situ pore pressures there is likely going to be a reverse in the impact of mud pressure applied on the wellbore wall. Where the mud pressure is too low to counteract the increased flow rate caused by high pore pressure gradients, the corresponding large drag forces will instigate rock failure in tension. At the other extreme of the spectrum, under parallel pore pressure conditions, if the mud pressure is too high, viscous and, in some instances, applied rapidly, the excess over the compressive forces which counterbalances the in situ pore pressure at the wellbore wall will cause rock failure in compression or shear when the rock compressive strength is exceeded.

Imposed drawdown conditions are shown to generate tensile forces due to high fluid flows in the vicinity of the wellbore. It is particularly observed where the rock material permeability is significantly low or the flow rate is very high resulting in large drag forces and negative effective radial stress. This phenomenon is consistent with Nouri et al. (2002) and Morita et al. (1998). Consequently, tensile stresses and strains will be generated at low mud weights which are insufficient to counteract the impact of influxes. On the other hand, compressive stresses and strains are generated if mud weights are excessively applied. The mud weight should be regulated such that it is not too low thereby allowing tensile failure, nor high enough to cause compressive failure.

This investigation is performed on a reservoir formation subjected to high in situ pore pressure and pore pressure gradient. The pore pressure at the wellbore face is 23.95 MPa with an initial overburden pore pressure gradient of 0.01 MPa/m and initial lateral pore pressure gradient of 2.13 MPa/m. The lateral pore pressure gradient is indicative of the reservoir drawdown. Both vertical and horizontal pore pressure gradients are considerably large (see Zhang 2011); the stress and strains generated are thus expected to be in accordance with field conditions under high naturally occurring pore pressure.

Establishing criteria for compressive failure and tensile failure of the wellbore is complicated because of the complexity of reservoir formations. The state of the rock is lithology dependent, and there are several factors that determine formation rock behaviour. Usually, tensile and compressive rock failure takes place when the respective rock tensile and compressive strength is exceeded by prevalent stresses. In wellbore stability analyses, initial rock failure does not necessarily jeopardise the stability of the wellbore, at least in the short term. Eventually, the onset of rock failure initiates a progression of mechanisms culminating in a critical state where an unstable condition is reached. An excellent measure of this is the critical radial inward and outward deformation or the critical radial tensile and compressive strain. Their actual values can be set as thresholds of the extent of strain that is tolerable, which is a function of the consequences in relation to the well stability. This may be case and site specific, varying with each drilling system and field condition. As a consequence of the primary focus of this research, an array of predefined critical tensile and compressive strains was tested. They were grouped in the following matching pairs: ±4.0e−4, ±6.0e−4, ±7.0e−4, ±8.0e−4, ±9.0e−4, and ±1.0e−3, where the positive and negative signs denote tension and compression, respectively.

There are several criteria that could be used to determine wellbore instability. Some of these are linked to established rock strength or failure criteria, such as Mohr–Coulomb, Mogi–Coulomb, Drucker–Prager and Modified Lade, where the main parameters are stress-related variables. The displacement or deformation of the wellbore is an alternative measure of its instability (e.g. Sheng et al. 2006). This focuses on the extent of wellbore deformation without recourse to the rock strength failure criteria. Adopting this form of criterion, radial strain is arbitrarily chosen, in this case, as an indicator of wellbore performance. This is also made to be consistent with the direction of application of mud pressure, since it is basically applied in the radial direction. In a similar manner, other displacement or strain parameters orientated tangentially or vertically to the wellbore may be suitable for this purpose.

In reality, rock tensile strength is significantly lower than its compressive strength. Nonetheless, in this analysis, hypothetical criterion values are used and the relative magnitudes of the pair were found to be irrelevant provided they remain consistent throughout each set of calculations. The emphasis, primarily, is to provide an accurate qualitative description of the trend.

4.1 Deterministic study

Figure 9 shows the results of the deterministic method in terms of the variation of the maximum radial tensile and compressive strains with mud pressure. The range of mud pressures is between 0 and 60 MPa. Where no mud pressure is applied the magnitude of radial tensile strain increases to a maximum of 6.75e−3. With a stepwise increase in mud pressure the maximum radial strain decreases at an almost linear rate to an almost stable value at a mud pressure of 30 MPa. Beyond 30 MPa the maximum radial tensile strain remains fairly constant, ranging from 0.50e−3 at 30 MPa to 0.44e−3 at 58 MPa. Between the mud pressures of 0 and 35 MPa, the maximum radial compressive strain stays relatively constant at approximately 1.0e−3, but immediately rises to 6.0e−3 at a linear rate from a mud pressure of 35 to 58 MPa.

The isotropic state of the horizontal stresses represents the in situ stress condition of the target formation. This equilibrium condition is affected once the wellbore is drilled, leading to a redistribution of the horizontal stresses. In cylindrical coordinates, these are represented by radial and tangential stresses. With respect to the wellbore axis, radial stresses act in both inward and outward directions resulting in corresponding compressive and tensile radial strains. The mud pressure is merely meant to act as a counterbalance. It is worth noting that stress measurements are not taken at a single point, but throughout the target segment of the wellbore.

The maximum radial strain values generated for varying mud pressures, as depicted in Fig. 10, confirm that the bounds of the safe mud pressure are dependent on stability criteria. Where it exists, the limit of the safe mud window increases with a stability criterion. For a strain criterion of ±4.0e−4 (Fig. 10a), there is no safe mud window; the wellbore is defined as totally unstable since the maximum compressive and tensile radial strains exceed the strain criterion. As the strain criterion is increased to ±6.0e−4 (Fig. 10b), the wellbore is only stable in tension above 29.5 MPa and still remains unstable in compression for the full range of applied mud pressure. An analogous trend is observed for a similar stepwise increase in strain criterion through ±7.0e−4, ±8.0e−4, ±9.0e−4 and ±1.0e−3. For instance, for a strain criterion of ±8.0e−4 and ±1.0e−3, tension-induced unstable conditions are reached if the mud pressure falls below 28.0 and 27.0 MPa, respectively, and the wellbore continues to be unstable in compression for all magnitudes of mud pressure (Fig. 10c, d). Note that for a strain criterion ≤ ±1.0e−3, the overall stability of the wellbore is regarded as being compromised since a true stable state is only obtained when both the tensile and compressive strains are lower than their corresponding failure/stability criteria.

Deterministic values: maximum radial strains at different mud pressures. a Strain criterion: ±4.0e−4. b Strain criterion: ±6.0e−4. c Strain criterion: ±8.0e−4. d Strain criterion: ±1.0e−3. e Strain criterion: ±1.2e−3. f Mud window: tensile strain criterion = +1.0e−3; compressive strain criterion = –1.1e−3

A further increase in strain criterion to ±1.2e−3 (Fig. 10e) establishes a safe mud window delineated by a lower bound of 26.0 MPa and an upper bound of 35.5 MPa. While the compressive integrity is still maintained, tensile failure and instability occur when the mud pressure declines below the lower limit. At the other end of the spectrum, compressive failure and instability occur at mud pressures above 35.5 MPa, whereas, under equivalent conditions, the maximum tensile strains are considered insignificant. It becomes immediately obvious that for a radial strain criterion greater than ±1.0e−3, a margin of safe mud pressure can be clearly delineated (Fig. 10d, f). Hence, if a radial tensile strain criterion of +1.0e−3 is combined with a radial compressive strain criterion of −1.1e−3, it is then possible to define a safe mud window, denoted by the base of the curve (Fig. 10f).

4.2 Stochastic study

Stochastic techniques promise to be a more rigorous approach in dealing with uncertainties in design and implementation. This can be manifested in the form of risks which are quantifiable. The extent to which risks are accurately assessed depends on the complexity of the process and the interchanging factors. Risks of drilling, completion and production of wells are mainly associated with wellbore instability. These forms of instability are defined in various ways. In this context, an unplanned fracturing of the reservoir by excessive pressure from injected fluid leading to loss in circulation is described as an unstable condition; well collapse or convergence caused by high compressive and shear stresses around the wellbore is defined as an unstable condition; also, reservoir erosion due to the weakening and detachment of rock is another unstable condition.

The causes of wellbore instability are undeniably attributed to drilling, completion and production practices. Nonetheless, the mechanical properties, physical properties and the structural constituents of the formation have an equal weighting. In this regard, the stochastic analysis employed in this study does not only emphasise the aspects of the operation during drilling, completion and operation, it also focuses, to a large extent, on the rock properties and their variations. Rock formations are naturally mostly heterogeneous. This heterogeneity is often difficult to estimate the wide range of incidences and the randomness at which they occur; however, their probability of occurrences may be encompassed in a stochastic procedure linking the likelihood of the existence of a combination of a set of controlling parameters on the performance of the wellbore. Factors affecting wellbore stability can be categorised as the in situ stress field, rock properties, pore pressures and mud pressure (Chen et al. 1996). An examination of the mechanisms of these factors indicates that changes in their magnitude, orientation and distribution are likely to have a profound impact on the stability of wellbores.

For this stochastic analysis the in situ stress field is incorporated in terms of the magnitude and orientation, but precluding residual stresses, thermal stresses and the history of tectonic events. The stress field is assumed to be hydrostatic and lithostatic with an extensional regime as described in Anderson (1951) and Eckert and Liu (2014), where \(\sigma_{\text{v}} > \sigma_{\text{H}} > \sigma_{\text{h}}\). A vertical borehole is used for the analysis implying drilling in the downward direction with zero deviation angle. The elastic modulus and Poisson ratio as elastic deformation parameters are used to represent the rock mechanical properties since the well integrity is significantly influenced by the allowable strain. For the physical property, the void ratio is used, as it characterises the compactness of the rock. A pore pressure gradient of 10 kPa/m is applied, measured as the hydrostatic pressure from sea level to the depth of the subsurface, which falls within the range for normal pressure conditions. Drilling and completion operations are restricted to mud pressure conditions applied in various ways as to represent balanced, underbalanced and overbalanced drillings.

The input parameters used to evaluate wellbore stability are derived from data that tend to be inconsistent. The uncertainty in data is thus manifested in the results of predicted safe mud pressures. The variability of each input parameter should be accounted for in a manner that properly represents their uncertainties. This can be accomplished by employing quantitative risk analysis (QRA), where, as applied by Moos et al. (2003) and McLellan and Hawkes (1998), cumulative distribution density (CDF) and probability density function (PDF) curves are used to measure uncertainties in input parameters. Where actual/real data are accessible, CDF and PDF curves that more accurately portray disparities in values of input parameters are used. In the absence of reliable data, the values of input parameters are varied between upper and lower bounds with the PDF defined by an appropriate distribution function. Examples of continuous distribution supported on bounded intervals are uniform distributions, truncated normal distributions, logit-normal distributions, logarithmic distributions and triangular distributions. An example of a continuous distribution supported on semi-infinite intervals is the log-normal distribution, and an example of a continuous distribution that takes values over the whole “real line” is the generalised normal (generalised Gaussian) distribution. At one end, if there is absolutely no indication of the likely values, the uniform distribution is adopted because of the high degree of caution required. At the other end, it is pertinent to use the triangular distribution where a specific value has been identified as most likely to occur.

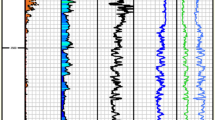

The choice of distribution function is dependent on what is considered most valid for predicting the variation in data. In some cases, such as presented by Gholami et al. (2015), beta-general, inverse-Gaussian and logistic distributions have been applied as functions for P-wave transit time log, porosity log, S-wave transit time log and density log data, respectively, even though they were unable to predict the whole variation of data. The normal or Gaussian distribution was adopted in this study, as it is a characteristic continuous probability distribution based on the central limit theorem. It is grounded on the premise that random variables individually drawn from independent distributions become normally distributed if the sample size is sufficiently large. This pattern of distribution has been successfully applied, for instance, by Moos et al. (2003) and Liang (2002) to quantify the distribution of input parameters for wellbore stability analyses. The probability density function of the normal distribution is given in Eq. (14). Hammersley sampling was employed to select from the prescribed range of values of individual input variables. Figure 11 describes the various histograms and associated probability curves (PDFs and CDFs) for the three design input variables following the implementation of this technique. Details of the corresponding statistical data for these distributions are presented in Table 4.

The Gaussian distribution of the design variables is further emphasised by reliability plots which indicate the probability of an arbitrary selection being above specific values between the given lower and upper bound limits of each parameter. The downward trend in probability of a random selection exceeding a given value of a design parameter is similar with each parameter (Fig. 12) and indicates that at the midpoint of the bound scale, equivalent to the mean, the probability of a random sample being greater than the mean value is 0.5. Invariably, this suggests that the probability of a random sample being less than the mean is 0.5. In Fig. 12, the reliability plots for the elastic modulus, Poisson ratio and void ratio are depicted. As reflected in the statistical data (Table 4), the minimum value, mean and maximum value of the elastic modulus are 1.18, 23.2 and 45.2 GPa, respectively. These have, in the same order, corresponding probabilities of being exceeded given as ≈ 1.0, ≈ 0.5 and 0.0. In the same manner, the probabilities for the minimum value (0.1006), mean (0.2212), and maximum value (0.3326) of Poisson ratio are ≈ 1.0, ≈ 0.5 and 0.0, respectively, and the probabilities for the minimum value (0.05099), mean (0.3389), and maximum value (0.5806) of void ratio are ≈ 1.0, ≈ 0.5 and 0.0, respectively.

The shape of the reliability plots for the design variables is somewhat similar to the s-shaped curve typically described by the sigmoid function (a form of the logistic function). This type of curve is usually created through logistic regression models. The major difference between the reliability plots and the s-shaped curve is the negative relationship between reliability and rock properties. As the rock property increases, the probability of a random choice of value being greater than a given magnitude decreases (Fig. 12). This is consistent for all three cases.

The Hammersley method was used to sample the distribution function. This technique belongs to the family of quasi-Monte Carlo methods and uses a quasi-random number generator for uniform sampling. The quasi-random sequence is an option that can be used instead of random or pseudo-random sequences. Whereas pseudo-random sequences exhibit statistical randomness since they are designed to imitate several properties of random sequences via deterministic procedures, quasi-random sequences implement an alternative deterministic algorithm that provides better uniformity in comparison with random sequences while still exploring the full design space. The standard Monte Carlo method which is based on a random or pseudo-random sequence is given to clumping of points, thereby lowering its accuracy. This constraint is overcome by quasi-Monte Carlo methods through correlations between points. Quasi-Monte Carlo methods are known to converge faster (Caflisch 1998) and provide low discrepancies, which is attributed to the improved uniformity. The advantages of quasi-Monte Carlo techniques are demonstrated in Caflisch (1998). The Hammersley method, being a class of quasi-Monte Carlo sequences, is able to provide reliable approximations while using fewer samples than random or pseudo-random sampling. Using this approach, the minimum number of runs is specified as

where N is the number of design variables. Notwithstanding, more iterations are necessary for stochastic simulation as better outputs are obtained with increasing iterations. The combination of design variables for the sequencing is presented in Fig. 13. Apparently, quasi-Monte Carlo techniques, on which the Hammersley method is based, are superior space fillers in comparison with random or pseudo-random techniques. Hammersley sampling was applied to generate the collection of triple data points representing values of the input parameters. The 2D and 3D design spaces showing the combinations of design variables selected as sample inputs are demonstrated in Figs. 14 and 15, respectively. The sample positions are evenly distributed across the design space irrespective of the parameter combinations, and this uniform spread is consistent for each pair of design variables (Fig. 14).

The two parameters chosen to represent the response of the wellbore and to monitor stability are the radial tensile strain and radial compressive strain. Because of the importance of the extrema, more emphasis is given to the maximum magnitudes of tensile and compressive radial strains. Although, as an alternative, principal strain values can also be used, relatively larger vertical strains caused by overburden loads may give a misleading indication of contributions from applied mud weights and reservoir drawdowns, which are better reflected by either radial or tangential (horizontal) strains. To demonstrate the wellbore response with changing mud pressures, the statistical distribution of maximum tensile and compressive strains after each series of iterations for specific mud pressures is constructed (Figs. 16, 17, 18). To illustrate the effect of mud pressure, results of three key magnitudes are presented (Figs. 16, 17, 18). These comprise

-

1.

the distribution of responses due to the application of mud pressures (PM = 15 MPa) significantly lower than the pore pressure at the vicinity of the wellbore (PP = 23.95 MPa), \(P_{\text{M}} \ll P_{\text{P}}\) (Fig. 16);

-

2.

the distribution of responses due to the application of mud pressures (PM = 23.95 MPa) equivalent to the pore pressure at the vicinity of the wellbore (PP = 23.95 MPa), \(P_{\text{M}} = P_{\text{P}}\) (Fig. 17); and

-

3.

the distribution of responses due to the application of mud pressures (PM = 50 MPa) significantly higher than the pore pressure in the vicinity of the wellbore (PP = 23.95 MPa), \(P_{\text{M}} \gg P_{\text{P}}\) (Fig. 18).

Generally, there is a higher frequency and hence higher probability of lower tensile and compressive strains in the range of distribution, which implies that within the context of any bound limit (upper and lower values) considered, there is a low tendency for higher strains to occur. For instance, given a mud weight of 15 MPa, there is an occurrence of maximum tensile strains within the range of 3.24e−4 (minimum) and 8.027e−3 (maximum) (Fig. 16a and Table 5). The CDF computed up to the maximum tensile strain of 1.865e−3 is 0.98. The cumulative probability of the maximum tensile strain exceeding this value (> 1.865e−3) is less than 0.02. Similarly, for the same mud weight, the maximum compressive strain falls within the range of −2.47e−3 (maximum) to −8.14e−5 (minimum) (Table 6). The CDF calculated from −2.47e−3 to −5.58e−4 is 0.04. Between −5.58e−4 and −8.14e−5 the CDF rapidly increases from 0.04 to 1.0. The same pattern occurs even when the mud pressure is considerably increased. At a mud weight of 50 MPa, the CDF for the maximum tensile strains ranging from 5.07e−5 to 1.37e−3 is 0.98, measured from 5.07e−5 to 3.65e−4. Thus, the probability of the maximum tensile strain surpassing 3.65e−4 is 0.02. For the spread of maximum compressive strain from −1.04e−2 to −3.97e−4, the CDF rises to 0.06 between −1.04e−2 and −1.91e−3 and then steeply advances to 1.0 between −1.91e−3 and −3.97e−4.

This implies that the probability of exceeding the maximum radial strain at the lower range is very high, but rapidly drops after only slight increases in strain magnitudes. Under a mud pressure of 15 MPa, the probability falls to 0.02 and 0.06 after a tensile strain of 2.0e−3 and a compressive strain of ≈ 5.0e−04 are attained, respectively (Figs. 19a, 20a). For a mud pressure of 23.95 MPa, the probability decreases to 0.02 and 0.06 at a tensile strain of 1.0e−3 and a compressive strain of ≈ 5.0e−04 (Figs. 19b, 20b). Likewise, for a mud pressure of 50 MPa, the probability reduces to 0.02 and 0.06 at a tensile strain of 4.0e−04 and a compressive strain of ≈ 2.0e−3, respectively (Figs. 19c, 20c).

The magnitude of tensile strain reduces as the mud pressure is raised (Fig. 21). Moreover, the rate of reduction in tensile strain decreases significantly at higher mud weights. Generally, below a mud pressure of 30 MPa, the rate of response in tensile strain is very sensitive resulting—for the lower bound strain value—in a higher reduction rate of ≈ 1.78e−5/MPa (Fig. 21a). Beyond a mud pressure of 30 MPa, the rate decreases remarkably to a constant value of ≈ 4.1e−7/MPa (Fig. 21a). For the upper bound strain (Fig. 21b), the rate of reduction is ≈ 4.415e−5/MPa when the mud pressure is below 30 MPa and ≈ 6.9e−7/MPa within the regime of mud pressures above 30 MPa. The general attenuation of tensile strain as the mud pressure increases implies a susceptibility of the wellbore to tensile-failure-related instabilities at relatively low mud pressures.

In contrast to the defined trend in tensile strain, the compressive strain increases with increases in mud pressure (Fig. 21). There is a remarkable difference in the progression in compressive strain between the lower and upper mud weight regimes with the rate of increase being considerably higher at higher mud pressures. Prior to the attainment of a mud pressure of 35 MPa, the lower bound compressive strain increases at a rate of 5.8e−7/MPa, then escalates sharply to a steep rate of 2.03e−5/MPa beyond this value (Fig. 21a). The same pattern occurs at the other end of the scale (the upper bound) (Fig. 21b), where the compressive strain increases at 6.4e−6 below 35 MPa and then accelerates to 5.25e−4 above 35 MPa. Consequently, the attenuation in tensile strain is followed by synchronised increments in compressive strain.

The stability of a wellbore can be described in terms of the tendency of failure of the rock surrounding the well. Where the rock around the wellbore fails, this immediately compromises the stability of the wellbore. Rock failure can be quantified in various ways. This include, for instance, the extent of brittle failure, the onset of a given strain criterion, and the proportion of rock and depth of area that reach the yield criterion. Because rock failure models are necessary for predicting rock behaviour, they are instrumental in determining wellbore stability conditions.