Abstract

Background

Behavior change interventions targeting self-regulation skills have generally shown promising effects. However, the psychological working mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Purpose

We examined theory-based mediators of a randomized controlled trial in couples targeting action control (i.e., continuously monitoring and evaluating an ongoing behavior). Self-reported action control was tested as the main mediating mechanism of physical activity adherence, and in addition self-efficacy and received social support from the partner.

Methods

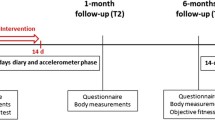

Overweight individuals (N = 121) and their heterosexual partners were randomly allocated to an intervention (information + action control text messages) or a control group (information only). Across a period of 28 days, participants reported on action control, self-efficacy, and received support in end-of-day diaries, and wore triaxial accelerometers to assess stable between-person differences in mediators and the outcome adherence to recommended daily activity levels (≥30 min of moderate activity in bouts of at least 10 min).

Results

On average, participants in the intervention group showed higher physical activity adherence levels and higher action control, self-efficacy, and received support compared to participants in the control group. Action control and received support emerged as mediating mechanisms, explaining 19.7 and 24.6% of the total intervention effect, respectively, in separate analyses, and 13.9 and 22.2% when analyzed simultaneously. No evidence emerged for self-efficacy as mediator.

Conclusions

Action control and received support partly explain the effects of an action control intervention on physical activity adherence levels. Continued research is needed to better understand what drives intervention effects to guide innovative and effective health promotion.

Trial Registration Number

(controlled-trials.com ISRCTN15705531)

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, et al.: Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. The Lancet. 2012, 380:247–257.

World Health Organization [WHO]: Physical activity. Fact Sheet. Retrieved June 27, 2016 from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/

Foster C, Hillsdon M, Thorogood M, Kaur A, Wedatilake T. Interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003180. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003180.pub2

Baranowski T, Anderson C, Carmack C Mediating variable framework in physical activity interventions. How are we doing? How might we do better? Am J Prev Med. 1998, 15:266–297.

Rhodes RE, Pfaeffli LA: Mediators of physical activity behaviour change among adult non-clinical populations: A review update. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition Physical Activity. 2010, 7:37.

Teixeira PJ, Carraca EV, Marques MM, et al.: Successful behavior change in obesity interventions in adults: A systematic review of self-regulation mediators. BMC Med. 2015, 13:84.

Lewis BA, Marcus BH, Pate RR, Dunn AL: Psychosocial mediators of physical activity behavior among adults and children. Am J Prev Med. 2002, 23:26–35.

Mann T, de Ridder D, Fujita K: Self-regulation of health behavior: Social psychological approaches to goal setting and goal striving. Health Psychology. 2013, 32:487–498.

Schwarzer R: Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2008, 57:1–29.

Sniehotta FF, Nagy G, Scholz U, Schwarzer R: The role of action control in implementing intentions during the first weeks of behaviour change. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2006, 45:87–106.

Carver CS, Scheier MF: On the self-regulation of behavior. Cambridge: Cambrigde University Press, 1998.

Fleig L, Lippke S, Pomp S, Schwarzer R: Intervention effects of exercise self-regulation on physical exercise and eating fruits and vegetables: A longitudinal study in orthopedic and cardiac rehabilitation. Prev Med. 2011, 53:182–187.

Prestwich A, Conner M, Hurling R, Ayres K, Morris B: An experimental test of control theory-based interventions for physical activity. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2016, 21:812–826.

Scholz U, Ochsner S, Luszczynska A: Comparing different boosters of planning interventions on changes in fat consumption in overweight and obese individuals: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Psychology. 2013, 48:604–615.

Bandura A: Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977, 84:191–215.

Olander EKO, Fletcher H, Williams S, et al.: What are the most effective techniques in changing obese individuals’ physical activity self-efficacy and behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2013, 10:1–15.

Anderson ES, Winett RA, Wojcik JR, Williams DM: Social cognitive mediators of change in a group randomized nutrition and physical activity intervention: Social support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations and self-regulation in the guide-to-health trial. J Health Psychol. 2010, 15:21–32.

Lewis BA, Williams DM, Martinson BC, Dunsiger S, Marcus BH: Healthy for life: A randomized trial examining physical activity outcomes and psychosocial mediators. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2013, 45:203–212.

Plotnikoff RC, Pickering MA, Rhodes RE, Courneya KS, Spence JC: A test of cognitive mediation in a 12-month physical activity workplace intervention: Does it explain behaviour change in women? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2010, 7:32.

Prestwich A, Conner MT, Lawton R, et al.: Randomized controlled trial of collaborative implementation intentions targeting working adults’ physical activity. Health Psychology. 2012, 31:486–495.

Burkert S, Scholz U, Gralla O, Roigas J, Knoll N: Dyadic planning of health-behavior change after prostatectomy: A randomized-controlled planning intervention. Social Science & Medicine. 2011, 73:783–792.

Schwarzer R, Knoll N: Social support. In D. French, K. Vedhara, A. A. Kaptein and J. Weinman (eds), Health Psychology. Malden: Blackwell, 2010, 283–293.

Sorkin DH, Mavandadi S, Rook KS, et al.: Dyadic collaboration in shared health behavior change: The effects of a randomized trial to test a lifestyle intervention for high-risk Latinas. Health Psychology. 2014, 33:566–575.

Prestwich A, Conner MT, Lawton RJ, et al.: Partner- and planning-based interventions to reduce fat consumption: Randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2014, 19:132–148.

Cutrona CE: Social Support in Couples. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1996.

Neff LA, Karney BR: Gender differences in social support: A question of skill or responsiveness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005, 88:79–90.

Carlson LE, Goodey E, Bennett MH, Taenzer P, Koopmans J: The addition of social support to a community-based large-group behavioral smoking cessation intervention: Improved cessation rates and gender differences. Addictive Behaviors. 2002, 27:547–559.

Scholz U, Ochsner S, Hornung R, Knoll N: Does social support really help to eat a low-fat diet? Main effects and gender differences of received social support within the Health Action Process Approach. Applied Psychology: Health and Well Being. 2013, 5:270–290.

Scholz U, Berli C: A Dyadic Action Control Trial in Overweight and Obese Couples (DYACTIC). BMC Public Health. 2014, 14:1321.

Berli C, Stadler G, Inauen J, Scholz U: Action control in dyads: A randomized controlled trial to promote physical activity in everyday life. Social Science & Medicine. 2016, 163:89–97.

Bundesamt für Sport [BASPO], Bundesamt für Gesundheit [BAG], Gesundheitsförderung Schweiz, Netzwerk Gesundheit und Bewegung Schweiz: Gesundheitswirksame Bewegung [Health-enhancing physical activity]. Magglingen: BASPO, 2009.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al.: The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2013, 46:81–95.

Choi L, Liu Z, Matthews CE, Buchowski MS: Validation of accelerometer wear and nonwear time classification algorithm. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2011, 43:357–364.

Sasaki JE, John D, Freedson PS: Validation and comparison of ActiGraph activity monitors. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2011, 14:411–416.

Cranford JA, Shrout PE, Iida M, et al.: A procedure for evaluating sensitivity to within-person change: Can mood measures in diary studies detect change reliably? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006, 32:917–929.

Scholz U, Nagy G, Schüz B, Ziegelmann JR: The role of motivational and volitional factors for self-regulated running training: Associations on the between- and within-person level. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2008, 47:421–439.

Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, Schwarzer R: Bridging the intention-behaviour gap: Planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. Psychology & Health. 2005, 20:143–160.

Bolger N, Zuckerman A, Kessler RC: Invisible support and adjustment to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000, 79:953–961.

Schulz U, Schwarzer R: Soziale Unterstützung bei der Krankheitsbewältigung: Die Berliner Social Support Skalen (BSSS). Diagnostica. 2003, 49:73–82.

Cerin E, Mackinnon DP: A commentary on current practice in mediating variable analyses in behavioural nutrition and physical activity. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12:1182–1188.

Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J: Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioal Research. 2004, 39:99–128.

Shrout PE, Bolger N: Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002, 7:422–445.

Hayes AF: Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach.: Guilford Press, New York, 2013.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF: Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavioral Research Methods. 2008, 40:879–891.

Fitzsimons GM, Finkel EJ: Interpersonal influences on self-regulation. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010, 19:101–105.

Banik A, Luszczynska A, Pawlowska I, et al.: Enabling, not cultivating: Received social support and self-efficacy explain quality of life after lung cancer surgery. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2017, 51:1–12.

Fuemmeler BF, Masse LC, Yaroch AL, et al.: Psychosocial mediation of fruit and vegetable consumption in the body and soul effectiveness trial. Health Psychology. 2006, 25:474–483.

Opdenacker J, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Auweele YV, Boen F: Psychosocial mediators of a lifestyle physical activity intervention in women. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2009, 10:595–601.

Baruth M, Wilcox S, Blair S, et al.: Psychosocial mediators of a faith-based physical activity intervention: Implications and lessons learned from null findings. Health Education Research. 2010, 25:645–655.

Donovan HS, Kwekkeboom KL, Rosenzweig MQ, Ward SE: Nonspecific effects in psychoeducational intervention research. West J Nurs Res. 2009, 31:983–998.

Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, et al.: Correlates of physical activity: Why are some people physically active and others not? The Lancet. 2012, 380:258–271.

Scholz U, Sniehotta FF, Schwarzer R: Predicting physical exercise in cardiac rehabilitation: The role of phase-specific self-efficacy beliefs. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 2005, 27:135–151.

Van Dyck D, Cardon G, Deforche B, et al.: Environmental and psychosocial correlates of accelerometer-assessed and self-reported physical activity in Belgian adults. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011, 18:235–245.

Thomas G, Fletcher GJ: Mind-reading accuracy in intimate relationships: Assessing the roles of the relationship, the target, and the judge. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003, 85:1079–1094.

Sallis JF, Taylor WC, Dowda M, Freeson PS, Pate RR: Correlates of vigorous physical activity for children in grades 1 through 12: Comparing parent-reported and objectively measured physical activity. Pediatric Exercise Science. 2002, 14:30–44.

Heron KE, Smyth JM: Ecological momentary interventions: Incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2010, 15:1–39.

MacKinnon, DP, Pirlott AG: Statistical approaches for enhancing causal interpretation of the M to Y relation in mediation analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2015, 19:30–43.

Preacher KJ: Advances in mediation analysis: A survey and synthesis of new developments. Annual Review of Psychology. 2015, 66:825–852.

Pituch KA, Stapleton LM: Distinguishing between cross- and cluster-level mediationprocesses in the cluster randomized trial. Sociological Methods & Research. 2012, 41:630–670.

Acknowledgements

This project (PP00P1_133632/1) and the first author (P2BEP1_158975) were funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards Authors Berli, Stadler, Shrout, Bolger, and Scholz declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

About this article

Cite this article

Berli, C., Stadler, G., Shrout, P.E. et al. Mediators of Physical Activity Adherence: Results from an Action Control Intervention in Couples. ann. behav. med. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-017-9923-z

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-017-9923-z