Abstract

In the context of large-scale surveys, pre-screening or longitudinal studies, researchers may be faced with the choice of using a brief measure of disgust propensity (DP: the general tendency to respond with the emotion of disgust to any given situation) or using no measure at all. The goal of the present study was to develop and validate such a short scale based on the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Disgust Propensity (QADP); Schienle et al., 2002). The participants (n = 1367; 80% female; mean age = 28 years) completed the QADP, and scales on disgust sensitivity and self-disgust. Brain structural data and disgust rating data were available for subsets of the total sample. Factor analysis revealed a five-factor structure of the QADP. A total of 10 items (two items for each factor) with the highest item-total correlations were selected. The resulting five-factor QADP (Cronbach’s alpha = .76) covers a broad range of disgust domains. The short QADP is correlated with the original questionnaire (r = .90), disgust sensitivity, disgust ratings for gustatory, olfactory and visual disgust elicitors, and volume in the insular cortex (a brain region involved in disgust processing). For future investigations, the QADP_brief can be a useful tool for assessing DP with high time efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The personality trait disgust propensity (DP: the general tendency to respond with the emotion of disgust to any given situation) has received increasing attention in various fields of research (e.g., clinical psychology, social psychology, neuroscience; for a review see Vicario et al., 2017).

Elevated levels of DP have been found in anxiety-related disorders, such as animal/ blood phobias, and contamination-related obsessive-compulsive disorders (see meta-analysis by Olatunji et al., 2017). Additionally, diagnoses of other mental disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, eating disorders, hypochondriasis) are associated with increased DP (see Olatunji and McKay, 2007; Davey, 2011; Schienle et al., 2003). In contrast, DP is reduced in specific neurological disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease; Ille et al., 2015).

In their review article, Kavaliers et al. (2019) discuss the relationship between disgust and social cognition. They point out that DP influences friend/ mate choices, what social groups we adhere to and support or reject (concepts of in-groups vs. out-groups), as well as social learning and empathy. Thus, DP plays a direct (or at least indirect) role in generating interpretation biases and psychopathological symptoms (Davey, 2011).

The insular cortex has been shown by several studies to be the main neural correlate of the feeling of disgust and DP (e.g., Calder et al., 2007; Craig, 2009; Scharmüller & Schienle, 2012, Wicker et al., 2003). Neuroimaging research has demonstrated that disgust stimuli (e.g., repulsive images, aversive smells) activate the insula (e.g., Wicker et al., 2003). Moreover, DP is associated with the structure of the insula. In a study by Scharmüller and Schienle (2012), scores on a DP measure were positively correlated with grey matter volume in the insula. The insula is a portion of the cerebral cortex folded deep within the lateral sulcus within each hemisphere of the mammalian brain. This brain region has diverse functions linked to the regulation of the body’s homeostasis (e.g. Wicker et al., 2003).

The mentioned findings underline the large spectrum of applications for measures of DP. Until now DP has been assessed with more or less extensive (multi-item) questionnaires (e.g., Haidt et al., 1994; Schienle et al., 2002; Tybur et al., 2009; van Overveld et al., 2011; Olatunji et al., 2012; Eickmeier et al., 2017; Polák et al., 2019). All mentioned questionnaires are useful tools to assess DP. They are characterized by (very) good reliability (at least internal-consistency reliability) and predictive validity. However, the use of these multi-item measures also has problematic aspects. For example, when DP is assessed together with other personality traits, the high number of items might induce boredom and fatigue in the respondents (Burisch, 1984). Moreover, within clinical contexts, an extended DP assessment is often challenging for the patients. Individuals with specific mental disorders (e.g. borderline personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder) often do not answer all items of the multi-item DP questionnaires. Missing data, especially when unequally distributed across clinical and healthy samples can bias results. Other useful applications of short DP instruments include large-scale surveys, pre-screening, and longitudinal studies. Short scales have also advantages in terms of validity and convenience (Thalmayer et al., 2011). Finally, researchers and practitioners in mental health services might simply not have enough time and resources to use a multi-item DP instrument.

The goal of the present study, therefore, was to develop a short DP measure without significantly narrowing the assessment of the construct (Widaman et al., 2011). The development was based on the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Disgust Propensity (QADP; Schienle et al., 2002). The QADP describes 37 situations, which have to be rated according to experienced disgust using a 5-point Likert scale (0 “not disgusting”; 4 “very disgusting”). The QADP has five subscales: (a) death/deformation (e.g., “Accidentally, you touched the stump of an arm-amputated man”), (b) body secretions (e.g., “Someone intensively smelling of sweat takes seat next to you in the bus”), (c) spoilage/decay (e.g., “During a walk through the forest you see a carcass”), (d) poor hygiene (e.g., “You touch the toilet seat with part of your body in a public restroom”), and (e) oral rejection (e.g., “You bite into a grilled grasshopper”). In a recent study, Petrowsky et al. (2010) reanalyzed the factor structure of the QADP with data from a large, representative sample (n = 2473). The authors found three domains for the QADP-R labeled core disgust (threat of disease through oral contact), animal-reminder disgust (reminders of our own mortality and animal origin), and contamination disgust (threat of contagion).

The aim of the present study was to develop and validate a short version of the QADP. We examined the psychometric properties of the scale (confirmatory factor analysis, internal consistency analysis). Furthermore, we tested the validity of the scale by means of correlations with similar traits (e.g., disgust sensitivity), disgust states (intensity of experienced disgust elicited by olfactory, gustatory, visual stimuli), and a neurobiological measure (grey matter volume in the insula).

Method

Participants

A total of 1367 participants who completed an online DP screening (QADP; Schienle et al., 2002) were included in the study. The sample was predominantly female (79.9%). Age ranged from 18 to 75 years (M = 28.05, SD = 10.05). For the purpose of the study, the sample was split into two independent data sets based on odd/even case numbers. The two samples were comparable in terms of mean age (t(795) = −.26, p = .79), gender (χ2(1) = 1.97, p = .16), education level (χ2(1) = 6.64, p = .25) and the mean score of the QADP (t(1365) = .02, p = .99).

The first sample included 683 participants (81.40% women). Participants’ age ranged from 18 to 66 years (M = 28.14; SD = 9.65). Of the 516 participants, 63.2% had completed high school, 19.0% higher education, and the remaining participants had practical occupational training.

The second sample included 684 participants (78.40% women). Participants’ age ranged from 18 to 75 years, with the mean age of 27.96 years (SD = 10.45). Of the 514, 68.9% had completed high school, 18.1% higher education, and the remaining participants had practical occupational training.

Participants were recruited through printed and electronic advertisements on boards at various sites across the city and at the University. All participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

For the validation of the short QADP, two additional questionnaires were administered.

The Scale for the Assessment of Disgust Sensitivity (SADS; Schienle et al., 2010) is a 7-item scale assessing difficulties in regulating one’s own feelings of disgust (e.g., ‘Experiencing disgust is stressful for me’). The internal consistency (Chronbach’s α) in this study was high in both samples (sample 1 and 2 = .89).

The Questionnaire for the Assessment of Self-Disgust (QASD; Schienle et al., 2014) assesses two subtypes of self-disgust; disgust-related self-concept (e.g., I find myself repulsive) and disgust-related behavior (e.g., I regret my behavior). The internal consistency (Chronbach’s α) for the personal self-disgust subscale was .92 (sample 1); .92 (sample 2), and for behavioral self-disgust .82 (sample 1); .79 (sample 2).

Statistical Analyses

Confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to assess the degree to which unitary, three-factor (Petrowsky et al., 2010) and five-factor (Schienle et al., 2002) structures of the original QADP fit the data. The analyses were conducted with R (version 1.1.436; R Core Team, 2018) using the lavaan package (Rossel, 2012). The parameter estimates were obtained using the weighted least squares (WLS; also knows as asymptotic distribution-free, or ADF), due to the violations of the normality assumption at the item-level (Brown, 2015). In order to evaluate absolute fit, Chi-square and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1998) were used. Comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) and the Tucker Lewis index (TLI; also known as non-normed fit index NNFI; Bentler and Bonett, 1980) were calculated as incremental fit indices. An RMSEA of .06 or less and CFI and TLI/NNFI values of .95 or more were considered to indicate a good fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005).

We checked for the potential common factor bias using Harman’s single factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The unrotated principal component analysis with a fixed one-factor solution indicated that the first factor did not account for the majority of the variance (32.52%). Thus, the common method variance does not seem to be a major issue in the present study.

Voxel-Based-Morphometry (VBM) Analyses

Brain structural data from 112 women (mean age: M = 25.32 years, SD = 7.92) were available (T1-weighted scans recorded with a 32-channel head coil, 3-T Siemens Skyra Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The scanning parameters were as followed: voxel size: 0.88 × 0.88 × 0.88 mm; 192 transverse slices, FoV = 224 mm, slice thickness: 0.88 mm, TE = 1.89 ms, TR = 1680 ms; TI = 1000 ms, flip-angle = 8°. Structural scans were analyzed with the Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12; r1318) implemented in SPM12 (v7219; Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/) for voxel-wise comparisons of grey matter volume (GMV). The structural images were first segmented into grey and white matter. Then the images were modulated to compensate for the effect of spatial normalization. The voxels were resliced to 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm. Finally, grey matter images were smoothed with a Gaussian kernel with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 8 mm.

Statistical analyses were carried out using random-effects models. We conducted regression analyses between DP and GMV for the left and right insular cortex. Insula masks were taken from the AAL atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer, et al., 2002). Furthermore, we used the total intracranial volume (TIV), age as well as the overall image quality as covariates. TIV was included as a covariate to correct for differences in head size. Results of the voxel intensity-based tests were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05 (corrected for family-wise error) and the voxel was part of a cluster with at least five contiguous voxels. All results were small volume corrected.

Analysis 1

Descriptive Item Analysis

We first examined the item-level descriptive statistics of the original 37-item scale (Supplementary Table 1). All items were rated as at least somewhat disgusting by the majority (i.e., > 50%) of the participants. Consistent with previous studies on DP (e.g., Petrowsky et al., 2010), distributions of individual items were not normal, as shown by the skewness and kurtosis statistics and Shapiro-Wilk test of normality (all ps < .001).

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

As seen from Table 1, from all of the estimated models, the five-factor model showed the best fit, both in terms of the absolute fit measures and the incremental fit indices. Standardized factor loadings ranged from .390 to .781.

In order to obtain a short scale that encompasses the entire range of the DP construct (Widaman et al., 2011), five sets of item intercorrelation analyses were conducted focusing on each of the original five subscales. Items were picked in sequence based on the magnitude of their corrected item-total correlations. Two items from each subscale with the highest item-total correlations were chosen, leaving us with a 10 item scale (Table 2).

Analysis 2

Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Short Scale

The second sample was used in order to validate the five-factor structure of the short version of the scale and validate its relationship with the original scale and other measures relevant for DP. As seen from Table 3, the overall fit statistics suggest a poor fit for the one-factor solution, whereas the five-factor solution suggests an excellent fit based on all indices of model fit. The standardized factor loadings range from .58 to .83 (see Table 4).

Internal Consistency

Due to a low number of items included in each subscale (i.e., two items per subscale), the internal consistency coefficients (Chronbach’s alpha) for the five subscales are low: oral defense (.64), hygiene (.59), spoilage (.63), body fluids (.64) and death (.78). For the total scale, however, the internal consistency is adequate (.76).

Validation

Construct Validity

We examined the correlations of the short scale with the original scale and other disgust-relevant constructs. To investigate the relationship between the short scale and the original scale, Levy’s correction (1964) was applied to obtain a ‘true score’. As seen in Table 5, the short scale is highly correlated with the original scale. Furthermore, the correlations with other disgust-relevant constructs, such as disgust sensitivity and self-disgust are all statistically significant.

Criterion Validity

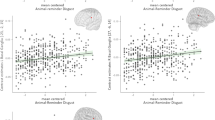

We conducted three validation experiments during which the participants were exposed to a) gustatory, b) olfactory and c) visual disgust elicitors after they had completed the QADP.

-

a)

A total of 200 women (mean age = 23.3 years, SD = 7.25 years) rinsed their mouth with 20 ml concentrated wormwood tea that was made with one teaspoon of dried herbal powder (Artemisia absinthium) per 300 ml of water. The tea steeped for exactly seven minutes and then cooled down to room temperature. The extremely bitter fluid was kept in the mouth for 30 s and then spat out. Subsequently, ratings for experienced disgust (1 = low; 9 = high) were collected. The QADP scores correlated positively with the disgust ratings (short QADP: r = .31, p < .001; original QADP: r = .32, p < .001).

-

b)

A total of 150 participants (74 men, 76 women, mean age = 24.0 years, SD = 4.02) were exposed to sweat samples of women and men. To generate the sweat samples, 3 women and 3 men participated in a 30-min outdoor exercise program (jogging). Prior to this exercise, an odorless cotton pad had been placed under the right shaved armpit of each participant and was attached with odorless adhesive. Directly after the exercise, each participant removed the cotton pad and placed it into a test tube. The tube was sealed and stored for 24 h at 20 °C (room temperature) in order to enhance the disgust intensity of the stimuli. The QADP scores were positively correlated with the mean disgust ratings for the sweat samples of males (short QADP: r = .34, p < .001; original QADP: r = .33, p < .001) and females (short QADP: r = .27. p < .001; original QADP: r = .29, p < .001).

-

c)

Fifty participants (25 men, 25 women, mean age = 23.4 years, SD = 2.7) were presented with images of typical disgust elicitors (e.g., maggots, dirty toilets) for 3 s each on the computer screen. The disgust ratings for the pictures were positively correlated with the QADP (original QADP: r = .53, p < .001; short QADP: r = .50, p < .001).

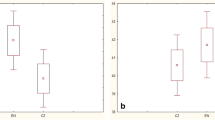

Gender Differences

Women scored higher on the short QADP (M = 2.59, SD = .64) compared to men (M = 2.07, SD = .72; t(682) = −8.40, p < .001).

VBM Results

The analysis of the brain-structural data revealed that the grey matter volume of the left insula was correlated with the original QADP (MNI coordinates: x,y,z: −38, −24, 21; t-value = 3.60, p (FWE) = .041) as well as with the short QADP (MNI coordinates: x,y,z: −38, −23, 15; t-value = 3.20, p (FWE) = .045).

Discussion

Brief DP instruments have many useful applications in large-scale surveys, prescreening, or longitudinal studies. We developed and validated such an instrument. The short QADP consists of 10 items that cover a broad range of disgust domains (e.g., spoilage, poor hygiene, body secretions, death, oral rejection). The total score of the short DP correlated with the total score of the original questionnaire with r = .90. Thus, the shared variance (81%) is sufficient. The scale has adequate internal consistency and can thus be used to reliably asses the personality trait DP. Due to the small number of items (and thus low internal consistency) for each subscale, we recommend the use of the total score when assessing DP with the short QADP. If researchers wish to assess specific disgust domains, the use of the original scale is advised.

The construct validity of the short QADP was assessed by correlating the total score with the scores for other disgust-related personality constructs (disgust sensitivity, self-disgust). The expected correlation pattern emerged. DP was moderately correlated with disgust sensitivity (r = .35). Similar coefficients have been found before (e.g., Schienle et al., 2010). The correlations between DP and self-disgust (personal: r = .22; behavioral: r = .13) were low. This finding is in line with other authors, who have observed only week associations between reports of self-disgust and common measures of DP (for a summary see Powell et al., 2015). The short QADP was also able to predict state disgust in experiments on visual, olfactory and gustatory disgust processing (reflecting sufficient criterion validity).

The validity of the short QADP was further substantiated by gender differences. Women scored higher compared to men. Gender differences in DP have been reported in numerous studies in the past (Druschel, & Sherman, 1999; Rohrmann et al., 2008; Schienle et al., 2005), with women consistently scoring higher.

Finally, a neural correlate of DP was investigated. We were able to show that both QADP versions (short, original) correlated with grey matter volume in the insular cortex. This finding is in line with other studies that identified the importance of the insula for disgust processing (e.g., Calder et al., 2007; Craig, 2009; Scharmüller & Schienle, 2012, Wicker et al., 2003).

Our study has some limitations, which have to be taken into account when interpreting the findings. Firstly, our sample predominately included women. Further studies using a representative sample should be conducted in order to evaluate the short DP scale. Furthermore, our study was not conducted in clinical settings, therefore clinical implications of the short QADP should be assessed in future studies.

In summary, we constructed a short measure of DP that has sound psychometric properties, encompasses a broad DP construct and correlates highly with the original QADP, thus providing the ability to compare the results of studies using the original version with studies using the short version. The short version includes only 10 items, yet is reliable and valid, which makes it a convenient option when researchers are interested in a quick assessment of the broad construct of DP.

References

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Burisch, M. (1984). Approaches to personality inventory construction: A comparison of merits. American Psychologist, 39(3), 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.39.3.214.

Calder, A. J., Beaver, J. D., Davis, M. H., van Ditzhuijzen, J., Keane, J., & Lawrence, A. D. (2007). Disgust sensitivity predicts the insula and pallidal response to pictures of disgusting foods. European Journal of Neuroscience, 25(11), 3422–3428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05604.x.

Craig, A. D. (2009). How do you feel — now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2555.

Davey, G. C. (2011). Disgust: the disease-avoidance emotion and its dysfunctions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1583), 3453–3465. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0039.

Druschel, B., & Sherman, M. (1999). Disgust sensitivity as a function of the Big Five and gender. Personality and Individual Differences, 26(4), 739–748. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00196-2.

Eickmeier, K., Hoffmann, L., & Banse, R. (2017). The 5-factor disgust scale: Development and validation of a comprehensive meause of disgust propensity. Europen Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35, 403–413.

Haidt, J., McCauley, C., & Rozin, P. (1994). Individual differences in sensitivty to disgust : A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors. Personality and Individual Differences, 16(5), 701–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)90212-7.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Ille, R., Wabnegger, A., Schwingenschuch, P., Katsching-Winter, P., Kögl-Wallner, M., Wenzel, K., & Schienle, A. (2015). Role of disgust propensity in parkinson’s disease: A voxel-based morphometry study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 21(4), 314–317. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135561771500017X.

Kavaliers, M., Ossenkopp, K. P., & Choleris, E. (2019). Social neuroscience of disgust. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 18(1), e12508. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbb.12508.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Methodology in the social sciences. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Levy, P. (1964). The correction for spurious correlation in the evaluation of short-form tests. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23(1), 84–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(196701)23:1<84::AID-JCLP2270230123>3.0.CO;2-2.

Olatunji, B. O., & McKay, D. (2007). Disgust and psychiatric illness: Have we remembered? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 457–459. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032631.

Olatunji, B. O., Adams, T., Ciesielski, B., David, B., Sarawgi, S., & Broman-Fulks, J. (2012). The three domains of disgust scale: factor structure, psychometric properties, and conceptual limitations. Assessment, 19(2), 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111432881.

Olatunji, B. O., Armstrong, T., & Elwood, L. (2017). Is disgust propensity associated with anxiety and related disorders? A qualitative review and meta-analysis of group comparison and correlational studies. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(4), 613–648. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616688879.

Petrowsky, K., Paul, S., Schmitzer, G., Roth, M., Brähler, E., & Albani, C. (2010). Domains of disgust sensitivity: revisited factor structure of the questionnaire for the assessment of disgust sensitivity (QADS) in a cross-sectional, representative german survey. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-10-95.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Polák, J., Landová, E., & Frynta, D. (2019). Undisguised disgust: a psychometric evaluation of a disgust propensity measure. Current Psychology, 38(3), 608–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9925-4.

Powell, P. A., Overton, P. G., & Simpson, J. (2015). The revolting self: Perspectives on the psychological, social, and clinical implications of self-directed disgust. New York, NY: Routledge.

R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Rohrmann, S., Hopp, H., & Quirin, M. (2008). Gender differences in psychophysiological responses to disgust. Journal of Psychophysiology, 22(2), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1027/0269-8803.22.2.65.

Rossel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36.

Scharmüller, W., & Schienle, A. (2012). Voxel-based morphometry of disgust propensity. Neuroscience Letters, 529(2), 172–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2012.09.004.

Schienle, A., Dietmaier, G., Leutgeb, V., & Ille, R. (2010). Eine Skala zur Erfassung der Ekelsensitivität (SEE). Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 39, 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1026/1616-3443/a000016.

Schienle, A., Ille, R., Sommer, M., & Arendasy, M. (2014). Diagnostik von selbstekel im rahmen der depression. Verhaltenstherapie, 24(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000360189.

Schienle, A., Schäfer, A., Stark, R., Walter, B., Franz, M., & Vaitl, D. (2003). Disgust sensitivity in psychiatric disorders: A questionnaire study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(12), 831–834. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000100928.99910.2d.

Schienle, A., Schäfer, A., Stark, R., Walter, B., & Vaitl, D. (2005). Gender differences in the processing of disgust- and fear-inducing pictures: An fMRI study. NeuroReport, 16(3), 277–280. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-200502280-00015.

Schienle, A., Walter, B., Stark, R., & Vaitl, D. (2002). Ein fragebogen zur erfassung der ekelempfindlichkeit (FEE). Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 31(2), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1026//1616-3443.31.2.110.

Steiger, J. H. (1998). A note on multiple sample extensions of the RMSEA fit index. Structural equation modeling, 5(4), 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519809540115.

Thalmayer, A. G., Saucier, G., & Eigenhuis, A. (2011). Comparative validity of short to medium-length big five and big six personality questionnaires. Psychological Assessment, 23(49), 995–1009. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024165.

Tybur, J., Lieberman, D., & Griskevicius, V. (2009). Microbes, mating, and morality: Individual differences in three functional domains of disgust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015474.

Tzourio-Mazoyer, N., Landeau, B., Papathanassiou, D., Crivello, F., Etard, O., Delcroix, N., Mazoyer, B., & Joliot, M. (2002). Automated anatomical labeling of activations in spm using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the mni mri single-subject brain. NeuroImage, 15(1), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2001.0978.

Van Overveld, M., de Jong, P., Peters, M. L., & Schouten, E. (2011). The disgust scale-R: A valid and reliable index to investigate separate disgust domains? Personality and Individual Differences, 51(3), 325–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.023.

Vicario, C. M., Rafal, R. D., Martino, D., & Avenanti, A. (2017). Core, social and moral disgust are bounded: A review on behavioral and neural bases of repugnance in clinical disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.05.008.

Wicker, B., Keysers, C., Plailly, J., Royet, J. P., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (2003). Both of us disgusted in My insula: the common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron, 40(3), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00679-2.

Widaman, K. F., Little, T. D., Preacher, K. J., & Sawalani, G. M. (2011). On creating and using short forms of scales in secondary research. In K. H. Trzesniewski, M. B. Donnellan, & R. E. Lucas (Eds.), Secondary data analysis: An introduction for psychologists (pp. 39–61). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The institutional review board approved the study.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after a full explanation of the study procedure.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Data will be made available upon request.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schienle, A., Zorjan, S. & Wabnegger, A. A brief measure of disgust propensity. Curr Psychol 41, 3687–3693 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00883-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00883-1