Abstract

This research investigated the relationship consequences of disclosing sexual secrets to a romantic partner. Analyses of data from a 39-item Internet questionnaire completed by 195 undergraduate students showed that revealing sex secrets to a romantic partner was associated with either neutral or positive relationship outcomes. Disclosure of sexual secrets almost never (< 5%) resulted in relationship dissolution and over a third of the sample reported that they appreciated the honest disclosure. In addition, keeping sex secrets was related to lower relationship satisfaction such that each additional sex secret being kept from a romantic partner was associated with a one-half point loss of satisfaction (on a 5-point relationship satisfaction scale). This decrease persisted when controlling for sex and race. Mediation analyses found support for the notion that the type of romantic relationship an individual is in explains part of the association between keeping secrets and relationship satisfaction. Implications and future research considerations are suggested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

College students are emerging adults who are increasingly away from their parents’ supervision, particularly for those who live on campus, leaving home for the first time. Their experimental behavior (Twenge et al. 2017), especially risky, permissive, casual sexual behaviors, generally seem to be part of a tolerant culture, focused more on hooking up and less on long-term committed relationships (Bogle 2008). However, college students still are likely to keep certain behaviors and sexual histories secret from their partners (Adams-Curtis and Forbes 2004; Borsari and Carey 1999; Lewis et al. 1997). Such secrets have been associated with negative physical and mental health outcomes for the secret keeper (Pennebaker 1989) in other age groups, so the psychological and social effects of keeping sexual secrets by emerging adults who are open about their sexuality is worthy of study.

It is not unusual for one or both partners in a romantic relationship to have a sexual secret in committed relationships, particularly if it is considered beneficial to their maintaining boundaries and privacy as an individual (Petronio and Child 2020). Whether to reveal a sex secret to a romantic partner is a “no, never” for some, a minor dilemma for others, or an agonizing issue for still others. The goals of this research were to identify the degree to which a sample of 195 undergraduates kept or revealed a sex secret from a romantic partner, the reaction of the partner, and outcome for the relationship. In particular, the researchers were interested in investigating if social attitudes encouraging more sexual freedom for college students resulted in their keeping or divulging sexual secrets and the partner reactions/relationship outcomes which followed.

Background

Sexual Disclosure in Relationships

While prior research exists on sexual relationships and secret-keeping, there is less literature focused on the affect of disclosure on individuals in romantic relationships. Sexual self-disclosure is defined as the willingness of an individual to share their sexual preferences or past behaviors with their romantic partner (Rehman et al. 2011; see also Snell et al., 1989 for sexual self-disclosure scales). Previously researched sexual behaviors and traumas that have been kept secret from romantic partners have included childhood sexual abuse (Gelik et al. 2018; Montigny Gauthier et al. 2019); HIV status (Wong et al. 2017); sexual orientation (Malterud and Bjorkman 2016); infidelity (Miller 2016); and sexual behavior with same same-sex partners (Newman et al. 2018).

As a society imbued with individualistic values, disclosure patterns in the U.S. may vary from countries with more collectivistic views. Until recently (e.g. the Trump era), the United States has stood firmly in its Westernized views of character and discipline. For Americans, the culturally accepted norm has been that telling the truth is “characteristic of a sincere and honest person” (Hofstede 1991). In terms of self-disclosure outside the context of sexual behavior, people in the West have been more likely than non-Westerners to engage in intimate self-disclosure (Tang et al. 2013), and since the sexual liberation movement of the 1960s, revealing sexual secrets have been part of these truth tellings (Tang et al. 2013). With its noteworthy prevalence in media, music, and other institutions, the cultural foundations of American society have primed the country to being a location apt for open dialogue regarding sexual themes and topics.

Keeping a sexual secret impacts the balance of trust within any relationship, while also having the potential to influence future relationships, whether romantic or explicitly sexual. Keeping a secret functions as a defense mechanism against any form of stigmatization, protecting one’s image in the market for a partner (Piazza and Bering 2010); however, keeping a secret has been associated with increased physical stress and dysfunctional in building intimacy in relationships (Cowan 2014). However, the revelation of a sexual secret may have different outcomes such that disclosing an extramarital affair may lead to strengthening or ending a marriage (Sharff 1978).

Secrets and Disclosure: When We Open Up

The decision to reveal (or not to reveal) sexual secrets to a partner can elicit internal feelings of stress out of feared social sanctions and damaging the existing romantic relationship (Brannon and Rauscher 2019; Brummett and Steuber 2015). The disclosure of sexual information between romantic partners is less likely to occur when a person anticipates that the disclosure will be followed by negative consequences. A conceptual framework that is useful for examining ways that romantic partners manage the disclosure of their sexual information is communication privacy management (CPM) theory (Petronio 2000, 2002). CPM theory provides a framework to understand how people actively manage private information in their daily lives (Petronio 2000, 2002; Petronio and Child 2020).

CPM theory emphasizes how individuals maintain ownership of their private information and serve as gatekeeper to control the flow of their sensitive information (Petronio 2000, 2002; Petronio and Child 2020). Sexual behaviors regarded as a type of private information to be shared judiciously out of feared negative reactions/consequences (Afifi and Caughlin 2006; Brannon and Rauscher 2019; Schrimshaw et al. 2014). Nichols (2012) found that individuals’ privacy concerns are predictive of refraining from disclosure of sexual history to romantic partners.

CPM theory includes the concept of boundary coordination which refers to the contextual factors in which actors share information and communicate in their relationships (Petronio 1991, 2002). Boundary coordination is composed of boundary ownership, boundary linkage, and boundary permeability (Brannon and Rauscher 2019; Petronio 2002; Petronio and Child 2020). Boundary permeability illustrates the level of private information that is being disclosed or not disclosed to someone else (Petronio and Child 2020). The level of thickness of privacy boundaries reflects the permeability of that boundary. Petronio and Child (2020) explained that when boundaries are more permeable there are fewer restrictions between the flow of private information (e.g. sex secrets) between two individuals due to feelings of trusting the partner with the information. However, as those boundaries thicken and owners enact greater levels of privacy management to limit access to their information, reflecting little trust in the partner’s reaction. Boundary permeability is salient in understanding the concealment or disclosure of sexual information between romantic partners, particularly when considering the seriousness (perceived or actual) of those sexual secrets.

Sexual Behavior in College: Keeping Secrets and Filling the Gaps

College is a time full of self-discovery and creating an identity for one’s self. It has also been observed as a time of experimentation, particularly related to sex and sexuality (Bogle 2008). One way students experiment is through hookups, which Garcia, Reiber, Massey, and Merriwether define as a “brief, uncommitted sexual encounter(s) among individuals who are not romantic partners or dating each other” (qtd by Klinger 2016). Though hookups today are less stigmatized than they were in previous generations, students often choose to keep prior hookups a secret since they fear a negative reaction. A gendered double standard places women at a greater disadvantage, as the likelihood of being stigmatized for casual sexual behavior is higher than for men (England et al. 2008). One problem with the idea of the hookup culture in that college students may believe hookups are far more common across campuses than is actually the case (Klinger 2016). As a result, many view hookups as a dominant and expected behavior, leading to the creation of judgements, secrets, and the dilemma of being open surrounding hookup culture behavior.

College hookup culture is also associated with changing attitudes towards romantic relationships and sexual freedom. Some research suggests that hooking up is replacing the need for romantic relationships on college campuses, though recent evidence challenges this assumption (Siebenbruner 2013). Rather than being seen as a replacement for romantic relationships, hookups are instead a source of fun and freedom for students as they navigate college life (Bogle 2008). Indeed, the most common context for sexual behavior remains within romantic relationships, with recent findings revealing sex in relationships occurring at approximately twice the rate of casual sex (Fielder et al. 2013). However, COVID-19 has reduced the frequency of hooking up with more stable relationships becoming the more common sexual context (Lehmiller et al. 2020).

Young adults define ideal relationships as a focus on exclusivity, trust, and commitment, with intimacy being the most prevalent motive to enter a relationship for emerging adults (Siebenbruner 2013). While sexual freedom and exploration are on the rise, especially within the social context of college life, young people are still drawn to forming lasting romantic relationships, creating a context in which their keeping secrets that diverge from this goal more likely.

Casual sex is a common experience for college-aged individuals who are exploring their sexual freedom (Owen et al. 2010). In fact, hookups are often seen as a way for young adults to meet their sexual needs or desires without committing to a monogamous romantic relationship (Shulman and Connolly 2013). It should be noted, however, that emerging adult scholars suggest that a large number of young adults’ prefer and expect their sexual experiences to occur in committed romantic partnerships (Olmstead et al. 2013, 2017), though often not planning for deeper commitments, such as marriage (Shulman and Connolly 2013). Recent literature identifies relationship readiness as an important factor among emerging adults who may not be ready to give up their newfound social freedoms and be committed to one person (LeFebvre and Carmack 2020). By contrast, emerging adults who indicate higher levels of readiness are more likely to perceive relationship commitment as a salient element in their romantic partnerships (Arnett 2015; Konstam et al. 2019). In summary, it appears that there is an overarching theme suggesting that young adults—particularly college students—delay deeply committed partnerships while pursuing more casual relationships to satisfy short-term needs, but there is still an expectation to form a committed relationship in the future.

Secrets between romantic partners are not uncommon, yet there are societal expectations that romantic partners are to share everything; when this open discourse fails to occur, there is often discord between partners (Afifi et al. 2011; Aldeis and Afifi 2015), even if partners ironically keep secrets because they are scared to damage their relationship (Easterling et al. 2012). Negative implications for romantic partnerships include the “chilling effect,” or partners’ failure disclose information to one another in anticipation of disapproval or rejection (Cloven and Roloff 1993; Roloff and Cloven 1990) which, in turn, decreases the level of openness in the communication process between partners (Easterling et al. 2012). In addition, “putative secrets,” or the realization that a secret is being kept (Aldeis and Afifi 2015) increases relationship conflict, emphasizing, again, that secrets are often problematic for the creation and maintenance of relationships (Afifi et al. 2011; Aldeis and Afifi 2015; Petronio and Child 2020).

Methods

Participants

Data for the study were obtained from a voluntary anonymous 39-item survey (developed by the authors) approved by the Institutional Review Board at mid-sized southeastern university and posted on the Internet, Fall (2019). Survey questions were created based on previous measures when applicable. For example, questions about relationship satisfaction were based on Hendrick’s (1988) Relationship Assessment Scale, while self-esteem and self-concept questions were based on Rosenberg’s (1965) and Robson’s (1989) measures, respectively. Questions about sexual secrets were derived from existing literature, particularly “mating” measures used by Piazza and Bering (2010: 297) in their research on emotional secrets. Students in the third author’s Courtship and Marriage as well as Marriage and Family courses were emailed the link and asked to complete the survey. Sociology faculty at each of the authors’ current universities also sent the survey link to the students in their introductory classes. Questions regarding gender, race/ethnicity, life-satisfaction etc. preceded questions about the respondents’ sex secrets. Since such content may elicit very sensitive memories, respondents were reminded that the survey was anonymous and voluntary—they could stop taking the survey at any time without penalty.

A total of 247 undergraduate students completed the survey. After removing respondents who did not answer questions related to our focal variables of interest or had sample sizes too small for meaningful analyses (i.e., only one respondent reported being transgender), the sample used for analysis contained 197 respondents. Of these respondents, 160 (81%) were female and 37 (18%) were male. Respondents ranged in age from 18 to 29, with the majority of respondents (53%) reporting that they were 18 years old at the time of study with an average age of 18.94 years. 135 (68%) of respondents were White, 33 (17%) were Black, 21 (11%) were Hispanic, and 15 (8%) reported being an other racial identity. The majority of respondents (179, 90%) reported that they were heterosexual, though 14 (7%) of respondents were bisexual; two (1%) were gay/lesbian; and 3 (2%) reported being an other sexual orientation. There were no statistically significant differences in sexual secrets and their impact by sexual orientation, so these analyses are not included below, however, they are available by request.

Measures

Independent Variables

Two independent variables were “Revealing Sexual Secrets” and “Number of Sexual Secrets.” Regarding the revelation of sex secrets, respondents were asked whether they had ever revealed a sex secret to a romantic partner; 89 (45.64%) of respondents had not revealed a sexual secret to a romantic partner while the majority (54.36%—106 respondents) had revealed a sexual secret to a romantic partner. Regarding the number of sexual secrets, respondents were asked to report the number of sex secrets they were currently keeping from their current partner or had kept from their most recent romantic partner. Choices ranged from 0 through 4, with the addition of “5 or more” and “Not Applicable” categories. Most respondents (62.12%) reported that they were not keeping sexual secrets from a partner, though 22.22% reported keeping one secret; 14.14% reported keeping 2–3 secrets; and 1.52% reported keeping 4 or more secrets from their current or most recent romantic partner.

Dependent Variables

Dependent variables of the study were relationship satisfaction, relationship formation, and disclosure outcomes. Current Relationship Satisfaction was measured by asking respondents to rate their current relationship satisfaction on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 5 (very satisfied). Scores ranged from 1 to 5 with an average relationship satisfaction rating of 4.08 out of 5.

Relationship Formation was measured by asking respondents how they felt “sexual secrets impact the formation (beginning) of a relationship.” Most (54.69%) respondents reported feeling neutral about the impact of a sex secret; 34.38% of respondents thought keeping a sex secret positively influenced the relationship; 10.94% of the respondents reported that sex secrets negatively impacted relationship formation.

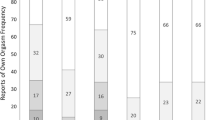

Disclosure Outcomes were measured in two ways. First, respondents were asked about the outcome of having told their partner a sex secret. Respondents chose all that applied from the following statements: disapproval/disgust from partner (5.05%); partners’ appreciation for sharing the information (38.89%); partner’s termination of the relationship (5.05%); personal relief (21.72%); personal regret (8.59%); other/not applicable (2.53%); and I have never revealed a sexual secret (19.19%). Hence over 60% of the respondents reported a positive reaction from telling a sex secret to a romantic partner.

Respondents were also asked the same question, only reporting what happened after their partner had disclosed a sex secret to them (the respondent). Respondents’ reactions included the following possible answers: disapproval/disgust toward partner (9.60%); appreciation for sharing the information (47.98%); dissolution of the relationship (2.02%); I have never been told a sexual secret (6.06%); and other/not applicable (17.17%). Hence, the most frequent reaction of being told a sex secret by a partner was positive for almost half of the respondents (48%).

Mediating Variable (Current Relationship Status)

Current Relationship Status asked respondents “which of the following categories best describes your current relationship status?” Over half (55.67%) of respondents were romantically involved/dating one person, serving as the referent. In addition, 39.18% of respondents were single or casually dating; 3.61% are cohabiting with their romantic partner; 0.52% were engaged; and 1.03% were married at the time of survey.

Control Variables

Sex of respondent was dummy coded into male (18.78%) and female (81.22%) due to small sample sizes, with female serving as the referent. Race/ethnicity was assessed by asking respondents to identify themselves based on the following categories: White, Black, Hispanic, Asian American/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaskan Native, Multiracial, and Other. Categories were combined to sustain cell size. White respondents comprised about 68.18% of the sample and served as the referent for analyses. Approximately 16.67% identified as Black, 10.61% identified as Hispanic, and 7.58% identified as other racial/ethnic group.

Analysis

The analysis employed both cross-tabulations using Pearson χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests, as well as regressions using STATA version 14. Tests analyzed how respondents thought sex secrets impacted relationships overall, as well as the outcomes for their relationships after sex secrets were revealed, either by the respondent or their partner. Regression analyses tested the impact of the number of sex secrets a respondent had on their current or most recent relationship satisfaction. Finally, the authors tested whether there was an association between the number of sex secrets kept and the relationship status of the respondent.

Findings

Sex Secrets: Amounts and Disclosure

The focus of the research was to identify/assess the perception of the impact of disclosure of a sex secrets on an individual’s romantic relationship. As previously mentioned, over half (54.63%) of respondents had revealed a sex secret to a romantic partner. Table 1 reveals that the number of sexual secrets a respondent had was significantly associated with their having revealed—or kept hidden—those secrets (p < 0.001). Specifically, the more sex secrets an individual had, the more likely they were to have revealed one of them to a romantic partner. In addition, most respondents felt that, at the beginning of a relationship, having a sex secret had either no impact or a positive impact on their relationship. Part of the explanation for these trends may come from two additional findings: (1) the non-significant change in relationship satisfaction by disclosure of sexual secrets (hence, no negative consequences from revealing a sex secret); and (2) the amount of secrets being kept by respondents from their recent or current romantic partners (thus, not needing to keep sex secrets). The vast majority of respondents either had no sexual secrets (62.12%) or one secret (22.22%) that they were keeping. Far fewer (1.52%) were keeping 4 or more secrets.

As the relationship between a couple continued, how did the partner react in terms of disapproval when the respondent disclosed a sex secret? Survey analyses revealed that negative outcomes were rare. Approximately, only five percent of the partners registered disapproval (5.05%, p < 0.01) or ended the relationship (5.05%, n.s.) when the respondent revealed a sex secret. Indeed, over a third (38.89%, p < 0.001) of the partners appreciated the romantic partner’s disclosure. Furthermore, 21.72% of the respondents who revealed a sex secret felt relief, compared to only 8.59% of respondents who regretted doing so (p < 0.001). To determine if there were differences in reactions depending on the discloser of sex secrets, respondents were asked about their reactions to being told a sex secret by their partner. Similarly, responses were overwhelmingly positive. Almost half of respondents (47.98%, p < 0.001) appreciated being told a sex secret, while only 9.60% (n.s.) of respondents reported either disapproving or being disgusted with their partner’s disclosure and 2.02% (n.s.) broke up with the partner who disclosed.

Sex Secrets and Relationship Satisfaction

Table 2 presents results from regression models that predicted relationship satisfaction by the number of sexual secrets a respondent was keeping. As shown in Model 1, there was a significant association (p < 0.001) between the number of sex secrets a respondent kept and their reported relationship satisfaction level. Specifically, for every additional sex secret kept, satisfaction decreased by almost half a point (− 0.403) on the 5-point scale. Specifically, Pearson chi2 and Fisher’s exact tests of the association supported this inverse relationship—respondents who reported having no secrets were most likely to report being very satisfied in their relationships (64.36%), while respondents reporting 1 or 2–3 sexual secrets were most likely to report being only mildly satisfied (38.89%) and neutral (38.10%), respectively (p < 0.001).

The association remained in Model 2, which added control variables (sex and race/ethnicity), although the coefficient decreased slightly from − 0.403 in Model 1 to − 0.342 in Model 2 (p < 0.01). Finally, Model 3 tested the influence of relationship status on the association between sex secret and relationship satisfaction. We found partial support for the hypothesis that relationship status helped explain the association—respondents with larger numbers of sexual secrets were still more likely to report lower levels of relationship satisfaction (− 0.124), though the association was no longer significant. Tests of mediation effects showed that approximately 54% of the effect of the number of sexual secrets on relationship satisfaction is indirect via relationship status.

To determine which types of relationships mattered more—or less—for the number of sexual secrets a respondent had, Pearson chi2 and Fisher’s exact tests were run. Single respondents were significantly more likely to report having 2–3 sexual secrets (64%) than their non-single counterparts (36%) (p < 0.05), and were twice as likely to report having 4 or more sexual secrets (66.67%) than their non-single counterparts (33.33%) (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in whether respondents in each of these relationship types had previously disclosed a sexual secret to a romantic partner. One interpretation is that casual daters may have felt that their private sexual history belonged to them whereas those in more involved relationships may have felt that their partner was entitled to have more access to their sexual history.

Discussion

Results revealed that, for respondents keeping one or more sexual secrets from a current or previous romantic partner (a little over 1/3 of the sample), outcomes for secret disclosure were overwhelmingly positive. Indeed, relationship satisfaction was not significantly altered by disclosure, supporting previous research emphasizing how disclosure can actually strengthen relationships (Sharff 1978) or, at the least, remove some of the negative stressors associated with secret-keeping (Cowan 2014). This was true for both the respondent and their partner, as secret disclosures toward either partner were overwhelmingly positive (47.98% and 38.89% appreciating the disclosure, respectively).

Keeping secrets from a romantic partner, whether due to college hookup expectations (Bogle 2008; Klinger 2016); fear of stigma (Brannon and Rauscher 2019; Piazza and Bering 2010); even boundary maintenance (Petronio and Child 2020) does have a significant impact on romantic relationships, however. Analyses found that the more secrets being kept by a respondent, the more likely they were to be less satisfied in their relationship, with non-secret-keepers reporting the most relationship satisfaction, similar to research on the “chilling effect” and the difficulty in creating and maintaining successful relationships when secrets remain (Aldeis and Afifi 2015; Petronio and Child 2020). The type of relationship also matters, with respondents in more casual, short-term relationships keeping more sexual secrets from partners, illustrating the concept of boundary permeability in particular (Petronio and Child 2020) in the need to restrict private information from casual linkages compared to longer term relationships.

Overall, even in a life course period that allows for more permissive sexual activity, college students still report keeping sexual secrets, even when they know divulging often ends positively. By maintaining these secrets, students are risking the quality of their relationships, as well as contributing to their own—and their partner’s—stress and mental health risks (Aldeis and Afifi 2015; Easterling et al. 2012). Though society promotes openness and honesty, there is still a gap between expectation and reality for emerging adults—those very individuals who are of age to create—and maintain—the very relationships they are keeping secrets about. Whether or not to keep a sex secret from a partner may seem like an individual concern, but the social implications of doing so are best shared with others.

Limitations

The data should be interpreted cautiously. Regarding the undergraduate sample, the data were skewed toward Whites (68%) and females (81%) and are hardly representative of the 17 million college and university undergraduates throughout the United States (National Center for Education Statistics 2020). Another limitation of the study is that it was cross-sectional. Respondents were asked to report on sex secret disclosure in a current or previous relationship at the time they took the survey, so we were unable to track fluctuations in their experiencing or revealing sex secrets over time. Finally, the survey only asked respondents about their partners’ having disclosed secrets to them, but did not survey the partner in question. Future research on sex secrets would ideally include both members of the romantic relationship to determine true mutual impact and reactions to the disclosure of sexual secrets.

In conclusion, among undergraduate college students, keeping sex secrets was associated with lower relationship satisfaction than revealing those secrets to a romantic partner. This difference was partly accounted for by the type of romantic relationship the respondent was in; however, the vast majority of disclosing experiences were met with either acceptance, relief, or neutrality. Future studies should use larger, more representative samples of adults and track satisfaction and secret disclosure over time.

Availability of Data and Material

Data is available by request from the corresponding author.

References

Adams-Curtis, L. E., & Forbes, G. B. (2004). College women’s experiences of sexual coercion: a review of cultural, perpetrator, victim, and situational variables. Trauma Violence Abuse, 5, 91–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838003262331.

Afifi, W. A., & Caughlin, J. P. (2006). A close look at revealing secrets and some consequences that follow. Communication Research, 33(6), 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650206293250.

Afifi, T. D., Joseph, A., & Aldeis, D. (2011). The “standards for openness hypothesis:” Why women find (conflict) avoidance more dissatisfying than men. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29, 102–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407511420193.

Aldeis, D., & Afifi, T. D. (2015). Putative secrets and conflict in romantic relationships over time. Communication Monographs, 82(2), 224–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2014.986747.

Arnett, J. J. (2015). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through early twenties (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Bogle, K. A. (2008). Hooking up: Sex, dating, and relationships on campus. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Borsari, B. E., & Carey, K. B. (1999). Understanding fraternity drinking: Five recurring themes in the literature, 1980 − 1998. Journal of American College Health, 48, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448489909595669.

Brannon, G. E., & Rauscher, E. A. (2019). Managing face while managing privacy: Factors that predict young adults' communication about sexually transmitted infections with romantic partners. Health Communication, 34(14), 1833–1844.

Brummett, E. A., & Steuber, K. R. (2015). To reveal or conceal? Privacy management processes among interracial romantic partners. Western Journal of Communication, 79(1), 22–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2014.943417.

Celik, G., Tahirogulu, A., Yoruldu, B., Varmis, D., Cekin, N., & Avci, A. (2018). Recantation of sexual abuse disclosure among child victims: Accommodation syndrome. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 27(6), 612–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2018.1477216.

Cloven, D. H., & Roloff, M. E. (1993). The chilling effect of aggressive potential on the expression of complaints in intimate relationships. Communication Mongraphs, 60, 198–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759309376309.

Cowan, S. K. (2014). Secrets and misperceptions: The creation of self-fulfilling illusions. Sociological Science, 1, 466–492. https://doi.org/10.15195/v1.a26.

Easterling, B., Knox, D., & Brackett, A. (2012). Secrets in romantic relationships: Does sexual orientation matter? Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 8, 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428x.2011.623928.

England, P., Shafer, E. F., & Fogarty, A. C. (2008). Hooking up and forming romantic relationships on today’s college campuses. In M. Kimmel & A. Aronson (Eds.), The Gendered Society Reader (3rd ed., pp. 531–593). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fielder, R. L., Carey, K. B., & Carey, M. P. (2013). Are hookups replacing romantic relationships? A longitudinal study of first-year female college students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(5), 657–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.001.

Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 93–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/352430.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. London: McGraw-Hill.

Klinger, L. (2016). Hookup culture on college campuses: Centering college women, communication barriers, and negative outcomes. College Student Affairs Leadership, 3(2). https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/csal/vol3/iss2/5.

Konstam, V., Curran, T., Celen-Demirtas, S., Karwin, S., Bryant, K., Andrews, B., et al. (2019). Commitment among unmarried emerging adults: Meaning expectations, and formation of relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(4), 1317–1342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407518762322.

LeFebvre, L. E., & Carmack, H. J. (2020). Catching feelings: Exploring commitment (un)readiness in emerging adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(1), 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519857472.

Lehmiller, J. J., Garcia, J. R., Gesselman, A. N., & Mark, K. P. (2020). Less sex, but more sexual diversity: Changes in sexual behavior during the COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Leisure Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1774016.

Lewis, J. E., Malow, R. M., & Ireland, S. J. (1997). HIV/AIDS risk in heterosexual college students. A review of a decade of literature. Journal of American College Health, 45, 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.1997.9936875.

Malterud, K. B., & Bjorkman, M. (2016). The invisible work of closeting: A qualitative study about strategies used by lesbian and gay persons to conceal their sexual orientation. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(10), 1339–1354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1157995.

Miller, L. (2016). Seeking the hiding: Working through parental infidelity. Clinical Social Work Journal, 44(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0561-2.

Montigny Gauthier, L., Vaillancourt-Morel, M. P., Rellini, A., Godbout, N., Charbonneau-Lefebvre, V., Desjardins, F., et al. (2019). The risk of telling: A dyadic perspective on romantic partners’ responses to child sexual abuse disclosure and their associations with sexual and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy., 45(3), 480–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12345.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). Condition of education 2020. NCES Annual Reports. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020144_AtAGlance.pdf.

Newman, C. E., Persson, A., Manolas, P., Schmidt, H. M., Ooi, C., Rutherford, A., et al. (2018). “So much is at stake”: Professional view on engaging heterosexually identified men who have sex with men with sexual health care in Australia. Sexuality Research and Social Policy: Journal of NSRC, 15(3), 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0291-z.

Nichols, W. L. (2012). Deception versus privacy management in discussion of sexual history. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 20, 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2012.665346.

Olmstead, S. B., Anders, K. M., & Conrad, K. A. (2017). Meanings for sex and commitment among first semester college men and women: A mixed-methods analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 1831–1842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0777-4.

Olmstead, S. B., Billen, R. M., Conrad, K. A., Pasley, K., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). Sex, commitment, and casual sex relationships among college men: A mixed-methods analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0047-z.

Owen, J. J., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Fincham, F. D. (2010). 'Hooking up' among college students: Demographic and psychosocial correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 653–663.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1989). Confession, inhibition, and disease. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 22, pp. 211–244). New York: Academic Press.

Petronio, S. (1991). Communication boundary management: A theoretical model of managing disclosure of private information between marital couples. Communication Theory, 1(4), 311–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.1991.tb00023.x.

Petronio, S. (2000). Balancing the secrets of Private disclosures. Mahwah, NJ, US: Laurence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Petronio, S. (2002). Boundaries of privacy: Dialectics of disclosure. New York, NY: State University of New York Press.

Petronio, S., & Child, J. T. (2020). Conceptualization and operationalization: Utility of communication privacy management theory. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.009.

Piazza, J., & Bering, J. M. (2010). The coevolution of secrecy and stigmatization: Evidence from the content of distressing secrets. Human Nature: An Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective, 21(3), 290–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-010-9090-4.

Rehman, U. S., Rellini, A. H., & Fallis, E. (2011). The importance of sexual self-disclosure to sexual satisfaction and functioning in committed relationships. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8, 3108–3115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02439.x.

Robson, P. J. (1989). Development of a new self-report questionnaire to measure self-esteem. Psychological Medicine, 19, 513–518. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329170001254X.

Roloff, M. E., & Cloven, D. H. (1990). The chilling effect in interpersonal relationships: The reluctance to speak one’s mind. In D. D. Cahn (Ed.), Intimates in conflict: A communication perspective (pp. 49–76). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Scharff, D. E. (1978). Truth and consequences in sex and marital therapy: The revelation of secrets in the therapeutic setting. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 4(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926237808403003.

Schrimshaw, E. W., Downing, M. J., Cohn, D. J., & Siegel, K. (2014). Conceptions of privacyand the non-disclosure of same-sex behaviour by behaviourally-bisexual men in heterosexual relationships. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 14(4), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2014.887779.

Shulman, S., & Connolly, J. (2013). The challenge of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood: Reconceptualization of the field. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696812467330.

Siebenbruner, J. (2013). Are college students replacing dating and romantic relationships with hooking up? Journal of College Student Development, 54(4), 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2013.0065.

Snell, W. E., Jr., Belk, S. S., Papini, D. R., & Clark, S. (1989). Development and validation of the Sexual Self-Disclosure Scale. Annals of Sex Research, 2, 307–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00849749.

Tang, N., Bensman, L., & Hatfield, E. (2013). Culture and sexual self-disclosure in intimate relationships. Interpersona: An International Journal on Personal Relationships, 7(2), 227–245.

Twenge, J. M., Sherman, R. A., & Wells, B. E. (2017). Sexual inactivity during young adulthood is more common among U.S. millenials and iGen: Age, period, and cohort effects on having no sexual partners after age 18. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0798-z.

Wong, W. C. W., Holroyd, E., Miu, H. Y. H., Wong, C. S., Zhao, Y., & Zhang, J. (2017). Secrets, shame and guilt: HIV disclosure in rural Chinese families from the perspective of caregivers. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 12(4), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2017.1344343.

Funding

No funding was garnered for this project. All work was completed voluntarily by researchers, with no incentives or profits provided by any university or external entity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest with this project.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. In addition, this project was approved by the university IRB prior to beginning the study.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Informed consent was established prior to beginning the survey. A statement was provided before questions were presented that detailed the goal of the study, the participant’s ability to stop the survey at any time, who to contact if the participant had any questions, and that by proceeding with the survey the participant agreed that they were over the age of 18.

Consent for Publication

The informed consent statement, mentioned in the above section, included consent for study participation and the publication of any significant or important findings from the research.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ritter, L.J., Martin, T., Fox, K. et al. “Thanks for Telling Me”: The Impact of Disclosing Sex Secrets on Romantic Relationships. Sexuality & Culture 25, 1124–1139 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09812-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09812-7