Abstract

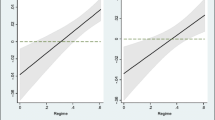

This paper reconsiders the proposition that remittances act as a political curse by reducing the poor’s demand for economic redistribution. With a newer democratization model focused on the demand for income protection from the rising groups in society, remittances may instead function as a political blessing. Since remittances increase income not only for the middle-class citizens that receive most of them, but also for the merchant and working classes that do not receive them per the multiplier effect, remittances should increase the demand for political rights to protect the economic assets of these societal groups. Using an error correction model with both country and year fixed effects, it reports a significant positive relationship between the change in democracy and net remittance inflows as a share of GDP using three different operational measures for democracy. It also reports results consistent with the underlying causal argument, showing how remittances increase national income and societal economic freedom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While both provide “redistribution” models, Boix (2003) and Acemoglu and Robinson (2006) make different predictions about how income inequality should influence the probability of democratization. Boix posits a linear negative relationship with the probability declining with greater inequality since the rich would have more to lose with redistributive democracy. Acemoglu and Robinson offer an inverted U-shaped relationship with the greatest probability of democratization at an intermediate level of inequality, arguing that when inequality is low, the poor also have less incentive to demand a more redistributive (i.e., democratic) regime.

In the Philippines, for example, estimates suggest that 80% of these remittance-receiving households fall within the middle class (Asian Development Bank 2010, 21).

We lead with the weakest result in our paper. Recall that our model is a very restrictive one, including a lagged dependent variable, country fixed effects, year fixed effects, and a control for regional democracy. In fact, the LRM for Remittances would be statistically significant at the 0.10 level using a one-tailed test, but this would not be appropriate since we are testing two competing hypotheses: the remittance curse versus the remittance blessing.

The results are also consistent with expectations when using the capital share of GDP measure of income inequality from Houle (2009), who expanded the dataset by Ortega and Rodriguez (2006). With the change in capital share as the dependent variable, the changes in remittances and lagged remittances are positively signed, but both are also statistically insignificant.

These data begin in 1970, but are only coded in five-year intervals through 2000, so we interpolate the missing internal values to obtain a more complete time series for the countries that are covered.

References

Abdih Y, Chami R, Dagher J, Montiel P. Remittances and institutions: are remittances a curse? World Dev. 2012;40(4):657–66.

Acemoglu D, Robinson JA. Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Acosta P, Calderon C, Fajnzylber P, Lopez H. What is the impact of international remittances on poverty and inequality in Latin America? World Dev. 2008;36(1):89–114.

Adams RH. Worker remittances and inequality in rural Egypt. Econ Dev Cult Chang. 1989;38(1):45–71.

Adams RH. International remittances and the household: analysis and review of global evidence. In: World Bank Policy Research Working Paper #4116. World Bank. Washington: DC; 2007.

Adams RH, Page J. Do international migration and remittances reduce poverty in developing countries? World Dev. 2005;33(10):1645–69.

Ahmed FZ. The perils of unearned foreign income: aid, remittances, and government survival. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2012;106(February):146–65.

Ahmed FZ. Remittances deteriorate governance. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2013;95(4):1166–82.

Allansson M, Melander E, Themnér L. Organized violence, 1989-2016. J Peace Res. 2017;54(4):574–87.

Altincekic C, Bearce DH. Why there should be no political foreign aid curse. World Dev. 2014;64(December):18–32.

Ansell BW, Samuels DJ. Inequality and democratization: a contraction approach. Comparative Political Studies. 2010;43(12):1543–74.

Ansell BW, Samuels DJ. Inequality and democratization: an elite-competition approach. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2014.

Asian Development Bank. Key indicators for Asia and the Pacific 2010. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank; 2010.

Barajas A, Chami R, Fullenkamp C, Gapen M, Montiel PJ. Do workers’ remittances promote economic growth?. IMF Working Paper WP/09/153; 2009. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Do-Workers-Remittances-Promote-Economic-Growth-23108. Accessed 12 May 2017.

Barham B, Boucher S. Migration, remittances, and inequality: estimating the net effects of migration on income distribution. J Dev Econ. 1998;55(2):307–31.

Bermeo SB. Aid is not oil: donor utility, heterogeneous aid, and the aid-democratization relationship. Int Organ. 2016;70:1): 1–32.

Beyene BM. The effects of international remittances on poverty and inequality in Ethiopia. J Dev Stud. 2014;50(10):1380–96.

Boix C. Democracy and redistribution. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Brown RPC, Jimenez E. Estimating the net effects of migration and remittances on poverty and inequality: comparison of Fiji and Tonga. J Int Dev. 2008;20(4):547–71.

Bueno de Mesquita B, Smith A, Siverson R, Morrow J. The logic of political survival. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2003.

Catrinescu N, Leon-Ledesma M, Piracha M, Quillin B. Remittances, institutions, and economic growth. World Dev. 2009;37(1):81–92.

Cheibub JA. Political regimes and the extractive capacity of governments: taxation in democracies and dictatorship. World Polit. 1998;50:349–76.

Cheibub JA, Gandhi J, Vreeland JR. Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice. 2010;143(1–2):67–101.

De Haan J, Sturm J-E. Does more democracy Lead to greater economic freedom? New evidence for developing countries. Eur J Polit Econ. 2003;19(3):547–63.

De Haas H. International migration, remittances and development: myths and facts. Third World Q. 2005;26(8):1269–84.

Dionne KY, Inman KL, Montinola GR. Another resource curse? The impact of remittances on political participation. Afrobarometer Working Paper No. 145. 2014. http://www.afrobarometer.org/files/documents/working_papers/Afropaperno145.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2018.

Djankov S, Montalvo JG, Reynal-Querol M. The curse of aid. J Econ Growth. 2008;13(3):169–94.

Doyle D. Remittances and social spending. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2015;109(4):785–802.

Durand J, Parrado EA, Massey DS. Migradollars and development: a reconsideration of the Mexican case. Int Migr Rev. 1996;30(2):423–44.

Easterly W. White man’s burden: why the west’s efforts to aid the rest have done so much ill and so little good. New York: Penguin Press; 2006.

Easterly W, Rebelo S. Fiscal policy and economic growth: an empirical investigation. J Monet Econ. 1993;32(3):417–58.

Easton MR, Montinola GR. Remittances, regime type, and government spending priorities. Stud Comp Int Dev. 2017;52(3):349–71.

Escribà-Folch A, Meseguer C, Wright J. Remittances and democratization. Int Stud Q. 2015;59(3):571–86.

Escribà-Folch A, Meseguer C, Wright J. Remittances and protest in dictatorships. Am J Polit Sci. 2018;62(4):889–904.

Galbraith JK. Inequality, unemployment and growth: new measures for old controversies. J Econ Inequal. 2009;7(2):189–206.

Geddes B, Wright J, Frantz E. Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: a new dataset. Perspect Polit. 2014;12(2):313–31.

Germano R. Migrants’ remittances and economic voting in the Mexican countryside. Elect Stud. 2013;32(4):875–85.

Giuliano P, Ruiz-Arranz M. Remittances, financial development, and growth. J Dev Econ. 2009;90(1):144–52.

Gleditsch KS, Ward MD. Double take: a reexamination of democracy and autocracy in modern polities. J Confl Resolut. 1997;41(3):361–83.

Gleditsch KS, Ward MD. Diffusion and the international context of democratization. Int Organ. 2006;60(4):911–33.

Gleditsch NP, Wallensteen P, Eriksson M, Sollenberg M, Strand H. Armed conflict 1946–2001: a new dataset. J Peace Res. 2002;39(5):615–37.

Glytsos NP. Measuring the income effects of migrant remittances: a methodological approach applied to Greece. Econ Dev Cult Chang. 1993;42(1):131–68.

Goodman GL, Hiskey JT. Exit without leaving: political disengagement in high migration municipalities in Mexico. Comparative Politics. 2008;40(2):169–88.

Gwartney J, Lawson R, Hall J. Economic freedom of the world: 2017 annual report. Vancouver, Canada: Fraser Institute; 2017. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom. Accessed 22 March 2018

Haber S, Menaldo V. Do natural resources fuel authoritarianism? A reappraisal of the resource curse. American Political Science Review. 2011;105:1): 1–26.

Houle C. Inequality and democracy: why inequality harms consolidation but does not affect democratization. World Polit. 2009;61(4):589–622.

Huntington S. The third wave: democratization in the late twentieth century. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press; 1991.

Kato J. Regressive taxation and the welfare state. path dependence and policy diffusion. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Kenworthy L. Jobs with equality. London: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Leblang DA. Property rights, democracy and economic growth. Polit Res Q. 1996;49(1):5–26.

Lindert PH. Growing public: vol. 1, the story: social spending and economic growth since the eighteenth century. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

Lipset SM. Some social requisites of democracy: economic development and political legitimacy. American Political Science Review. 1959;53(March):69–105.

Mahdavy H. The patterns and problems of economic development in rentier states: the case of Iran. In: Cook MA, editor. Studies in the economic history of the Middle East. London: Oxford University Press; 1970. p. 37–61.

Marshall MG, Gurr TR, Jaggers K. Polity IV project: political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2013. Severn, MD: Center for Systemic Peace; 2014. http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html. Accessed 10 Oct 2014

McKenzie D, Rapoport H. Network effects and the dynamics of migration and inequality: theory and evidence from Mexico. J Dev Econ. 2007;84(1):1–24.

Meltzer AH, Richard SF. A rational theory of the size of government. J Polit Econ. 1981;89(5):914–27.

Mulligan CB, Gil R, Sala-i-Martin X. Do democracies have different public policies than nondemocracies? J Econ Perspect. 2004;18(1):51–74.

Nishat M, Bilgrami N. The impact of migrant worker’s remittances on Pakistan economy. Pak Econ Soc Rev. 1991;29(1):21–41.

OECD. International migrant outlook. Paris, France: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2006.

Ortega D, Rodriguez F. Are capital shares higher in poor countries? Evidence from industrial surveys. In: Unpublished manuscript: Corporación Andina de Fomento and Wesleyan University; 2006.

Pérez-Armendáriz C, Crow D. Do migrants remit democracy? International migration, political beliefs, and behavior in Mexico. Comp Polit Stud. 2010;43(1):119–48.

Pfutze T. Clientelism vs. social learning: the electoral effects of international migration. Int Stud Q. 2014;58(2):295–307.

Ratha D. Workers’ remittances: an important and stable source of external development finance. In: Maimbo SM, Ratha D, editors. Remittances: development impact and future prospects. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2005. p. 19–51.

Ratha DA, Gemechu A, Silwal A. Remittances to developing countries will surpass 400 billion dollar in 2012. Migration and Development Brief # 19. Washington DC: World Bank; 2012. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/563761468331462418/Remittances-to-developing-countries-will-surpass-400-billion-dollar-in-2012. Accessed 1 March 2017.

Rigobon R, Rodrik D. Rule of law, democracy, openness, and income. Econ Transit. 2005;13(3):533–64.

Ross ML. Does oil hinder democracy? World Polit. 2001;53(April):325–61.

Taylor JE. The new economics of labor migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. Int Migr. 1999;37(1):63–86.

Timmons JF. Taxation and representation in recent history. J Polit. 2010;72(1):191–208.

Tyburski MD. The resource curse reversed? Remittances and corruption in Mexico. Int Stud Q. 2012;56(2):339–50.

Tyburski MD. Curse or cure? Migrant remittances and corruption. J Polit. 2014;76(3):814–24.

UCDP, PRIO. The UCDD/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset (V. 17.2). Oslo, Norway: International Peace Research Institute; 2017. http://ucdp.uu.se/downloads/. Accessed 22 March 2018

Vanhanen T. Measures of democracy 1810-2010 [computer file]. FSD1289, version 5.0 (2011- 07-07). Tampere: Finnish Social Science Data Archive [distributor]; 2011. Accessed October 10, 2014

Woodruff C, Zenteno R. Migration networks and microenterprises in Mexico. J Dev Econ. 2007;82(2):509–28.

World Bank: World development indicators. 2014. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators. Accessed 10 Oct 2014.

Yang D. International migration, remittances and household investment: evidence from Philippine migrants’ exchange rate shocks. Econ J. 2008;118(528):591–630.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bearce, D.H., Park, S. Why Remittances Are a Political Blessing and Not a Curse. St Comp Int Dev 54, 164–184 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-018-9277-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-018-9277-y