Abstract

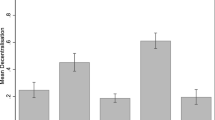

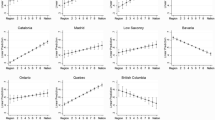

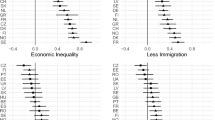

This article presents three related findings on regional decentralization. We use an original dataset collected in Uganda to establish, for the first time in a developing country context, that individuals have meaningful preferences over the degree of regional decentralization they desire, ranging from centralism to secessionism. Second, multilevel models suggest that a small share of this variation is explained at the district and ethnic group levels. The preference for regional decentralization monotonically increases with an ethnic group or a district’s average ethnic attachment. However, the relationship with an ethnic group or district’s income is U-shaped: both the richest and the poorest groups desire more regionalism, reconciling interest-based and identity-based explanations for regionalism. Finally, we show that higher individual ethnic attachment increases preferences for regionalism using fixed effects and a new matching method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, ethnic diversity undermines economic performance and public good provision (Easterly and Levine 1997; Habyarimana et al. 2007); ethnic boundary institutions negatively affect government responses to pandemics like HIV/AIDS (Lieberman 2009); ethnic groups often drive secessionist movements (Horowitz 1985; Hechter 2000); and national leaders tend to favor their own ethnic group (Franck and Rainer 2012; Kramon and Posner 2016).

A territorial cleavage exists when a self-conscious minority is geographically concentrated (Amoretti and Bermeo 2004, p. 2).

The one nationwide study of preferences for devolution or regionalism comes from a study of Belgian MPs (Dodeigne et al. 2016).

Fearon (2003), for instance, lists Uganda as the third most ethnically fractionalized country in Africa and fourth most in the world. His dataset lists 18 ethnic groups that comprise 1% or more of the population in Uganda, which is more than any other country in Africa after Tanzania, with 21.

The 66% is not statistically different from 0 because the number of secessionists in Uganda is low regardless of their level of ethnic attachment.

See Sambanis and Milanovic (2011) for a concise literature review.

Horowitz also distinguishes between backward and advanced groups, such that there are advanced groups in backward regions and backward groups in advanced regions. However, in both cases, he correctly notes a general lack of interest in secession or separatism due to a more complex calculation of costs and benefits.

We examine the empirical correlates of individual-level ethnic attachment in “Results”.

In all of these cases, the data was collected after regional governments had already been established. Our case study allows us to examine the same relationship without any such government yet.

Note that this view is not homogeneous within the social sciences. Hechter (2013), for instance, notes the ways in which alien or non-native rulers can become legitimate through effective and fair governance.

An alternative means to the same end is posited by Alesina and Spolaore (2003), who suggest that the size and borders of states are drawn by trading off economies of scale and heterogeneous preferences.

The lone exception was a brief attempt at secession among the Bakonjo and Baamba in western Uganda in the early 1960s.

Two vignettes in the Online Appendix allude to the financial under-provision that districts suffer (Fig. 7) and to the clientelistic use of new districts (Fig. 8).

The only kingdom not restored was Ankole, which happens to be the home territory for President Museveni. The ostensible reason given for not restoring Ankole was its local unpopularity; however, some have speculated that another reason was that the Omugabe (king) of Ankole would be, if restored to his position, politically superior to Museveni himself according to traditional norms.

We were able to insert the ethnicity of the respondent from a previous answer thanks to using around 80 tablet computers, one for each Ugandan enumerator. This question is identical to one asked in Afrobarometer surveys; elsewhere it has become known as the “Moreno question” after the Spanish political scientist who pioneered its use in Scotland and Catalonia.

Most of the survey took place between the two questions and was unrelated to ethnicity.

44% of our sample had not finished primary school, in line with the national average. Reassuringly, decentralization preferences by region are almost identical between the 44% that did not finish primary and the 56% that did.

We conducted two focus groups of six members each in July of 2012. Discussions lasted roughly two hours in each case. We instructed the organizer to recruit three males and three females in each group from different ethnic groups that did not know each other beforehand. The focus groups were ethnically mixed to foster engaged discussions.

Tables 5 and 6 in the Online Appendix present the corresponding statistical results.

The linear and quadratic fits in the right scatterplot of Fig. 5 do not include Mubende, an extreme outlier likely due to small sample size.

In “Regionalism as a Deviation from a Centralist Status Quo” we defined regionalism as a deviation from the centralism. We can think of the dependent variable as a latent variable representation of that deviation (Y ∗) for which four outcomes are observed. Hence, we have Y i ∈{1, 2, 3, 4} with each corresponding respectively to centralism, autonomism, federalism, and secessionism. Each individual chooses the institutional design closest to his ideal point \(Y_{i}^{*}\).

Results are quantitatively almost identical for all coefficients of interests whether we use survey weights or not and whether we use restricted MLE or simple MLE. Steenbergen and Jones (2002, p. 226) suggest restricted MLE to reduce bias in models with few level 2 observations, but results do not change: the random intercepts standard deviation changes from .023 to .024 and the individual-level ethnic attachment coefficient from .057 to .059. In the article, we present the results with simple MLE to be able to include survey weights and clustered standard errors at the district level in the model.

In generalized linear models like an ordered logit, β might not be consistent if the number of groups j is large and the number of observations i is small. Because of the large sample size (n > 2800), including 40 district indicators and 27 group indicators simultaneously should not affect consistency.

Region fixed effects are de facto included in models 3 and 4 since regions are a linear combination of districts.

We ran the models with an interaction between ethnic attachment and ethnic regional majority to ascertain whether the effect of ethnic attachment was stronger among the ethnic majority. The effect becomes insignificant as soon as we include some fixed effects (models 2 to 4).

Variables include gender, education, work frequency, wealth, public services received (to proxy for welfare), trust in Ugandans, trust in coethnics, trust in the local council chairman (LC3), trust in the governing party (NRM), perceptions of corruption, residence in a kingdom, and membership in the district’s ethnic majority. Some of those covariates may not be “pre-treatment,” notably the trust battery. As we mention in several table footnotes, the effect of ethnic attachment is unaffected by the trust battery—trust variables are not correlated with ethnic attachment (ρ < 0.05).

Using potential outcomes notation, the problem is that Y i (t)

T

i

|X

i

∀t ∈ T. The method ensures that for a variable T, at least with respect to observables, we have that Y

i

(t) ⊥ ⊥ T

i

|X

i

∀t ∈ T.

T

i

|X

i

∀t ∈ T. The method ensures that for a variable T, at least with respect to observables, we have that Y

i

(t) ⊥ ⊥ T

i

|X

i

∀t ∈ T.

The 66% is not statistically different from 0 because the number of secessionists in Uganda is low regardless of their level of ethnic attachment.

The serious shortcomings of subnational public finance data in developing countries are evident in current datasets such as the Government Finance Statistics published by the International Monetary Fund.

References

Ahlerup, P, Olsson O. The roots of ethnic diversity. J Econ Growth 2012;17 (2):71–102.

Alesina, A, Spolaore E. 2003. The size of nations. MIT Press.

Allport, G W. The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Books; 1954.

Amoretti, U M, Bermeo N. Federalism and territorial cleavages. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2004.

Ashraf, Q, Galor O. The “Out of Africa” hypothesis, human genetic diversity, and comparative economic development. Am Econ Rev 2013;103(1):1–46.

Bakke, K M, Wibbels E. Diversity, disparity, and civil conflict in federal states. World Politics 2006;59(1):1–50.

Barcikowski, R S. Statistical power with group mean as the unit of analysis. J Educ Behav Stat 1981;6(3):267–85.

Bleaney, M, Dimico A. State history, historical legitimacy and modern ethnic diversity. Eur J Polit Econ 2016;43:159–70.

Boylan, B M. In pursuit of independence: the political economy of Catalonia’s secessionist movement. Nations and Nationalism 2015;21(4):761–85.

Breton, A. The economics of nationalism. J Polit Econ 1964;72(4):376–86.

Burg, S L. Identity, grievances, and popular mobilization for independence in catalonia. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 2015;21(3):289–312.

Cederman, L -E, Weidmann N B, Gleditsch K S. Horizontal inequalities and ethnonationalist civil war: a global comparison. Am Polit Sci Rev 2011;105(3):478–95.

Cilliers, J, Dube O, Siddiqi B. 2012. ‘White man’s burden’? A field experiment on generosity and foreigner presence. Working paper.

Deiwiks, C, Cederman L -E, Gleditsch K S. Inequality and conflict in federations. J Peace Res 2012;49(2):289–304.

Dodeigne, J, Gramme P, Reuchamps M, Sinardet D. Beyond linguistic and party homogeneity: determinants of Belgian MPs’ preferences on federalism and state reform. Party Polit 2016;22(4):427–39.

Easterly, W, Levine R. Africas’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ 1997;112(4):1203–50.

Eifert, B, Miguel E, Posner D N. Political competition and ethnic identification in Africa. Am J Polit Sci 2010;54(89):494–510.

Fearon, J D. Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. J Econ Growth 2003;8(2): 195–222.

Findley, M G, Harris AS, Milner HV, Nielson DL. 2017. “Who Controls Foreign Aid? Elite versus Public Perceptions of Donor Influence in Aid-Dependent Uganda.” International Organization.

Franck, R, Rainer I. Does the leader’s ethnicity matter? ethnic favoritism, education, and health in Sub-Saharan Africa. Am Polit Sci Rev 2012;106(02):294–325.

Gellner, E. Nations and nationalism. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press; 1983.

Goodfellow, T. Legal manoeuvres and violence: law making, protest and semi-authoritarianism in Uganda. Dev Chang 2014;45(4):753–76.

Government of Uganda. 2005. Constitution amendment (no 2) act, 2005.

Government of Uganda. 2012. Review of local government financing. Technical report local government finance commission Kampala.

Green, ED. Patronage, district creation, and reform in Uganda. Stud Comp Int Dev 2010;45:83–103.

Green, E D. Explaining African ethnic diversity. Int Polit Sci Rev 2013;34(3): 235–53.

Green, E D. Decentralization and development in contemporary Uganda. Regional and Federal Studies 2015;25(5):491–508.

Grossman, G, Lewis JI. Administrative unit proliferation. Am Polit Sci Rev 2014;108(01):196–217.

Habyarimana, J, Humphreys M, Posner D N, Weinstein J M. Why does ethnic diversity undermine public goods provision? Am Polit Sci Rev 2007;101(4): 709–25.

Hagendoorn, L, Poppe E, Minescu A. Support for separatism in ethnic republics of the Russian Federation. Eur Asia Stud 2008;60(3):353–73.

Hechter, M. The political economy of ethnic change. Am J Sociol 1974;79(5): 1151–78.

Hechter, M. Internal colonialism: the celtic fringe in british national development 1536–1966. London: Routledge; 1975.

Hechter, M. Containing nationalism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Hechter, M. Alien rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

Horowitz, D L. Ethnic groups in conflict. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1985.

Kramon, E, Posner D N. Ethnic favoritism in education in Kenya. Quarterly Journal of Political Science 2016;11:1–58.

Lieberman, E. Boundaries of contagion. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press; 2009.

Mann, M. The dark side of democracy: explaining ethnic cleansing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Michalopoulos, S. The origins of ethnolinguistic diversity. Am Econ Rev 2012; 102(4):1508–39.

Minority Rights Group International. 2001. Map of ethnic groups and tribes of Uganda. Technical report. http://reliefweb.int/map/uganda/ethnographic-uganda.

Muñoz, J, Tormos R. Economic expectations and support for secession in Catalonia: between causality and rationalization. Eur Polit Sci Rev 2015;7(2):315–41.

Ratkovic, M. 2014. Balancing within the margin: causal effect estimation with support vector machines.

Ricart-Huguet, J, Paluck EL. When the sorting hat sorts randomly: a natural experiment on culture ; 2017.

Robinson, A L. National versus ethnic identification in africa: modernization, colonial legacy, and the origins of territorial nationalism. World Politics 2014;66(4): 709–46.

Roeder, P G. Power dividing as an alternative to ethnic power sharing. In: Roeder P G and Rothchild D, editors. Sustainable peace: power and democracy after civil wars. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press; 2005. p. 51–82.

Sambanis, N, Milanovic B. 2011. Explaining the demand for sovereignty. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (November).

Selassie, A G. Ethnic federalism: its promise and pitfalls for Africa. The Yale Journal of International Law 2003;28:51–107.

Steenbergen, M R, Jones B S. Modeling multilevel data structures. Am J Polit Sci 2002;46(1):218–237.

UBOS. Statistical abstract. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS); 2014.

Varshney, A. Ethnic conflict and civic life: Hindus and muslims in India. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2003.

Weber, E. Peasants into frenchmen: the modernization of rural France, 1870–1914. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1976.

Wimmer, A. Nationalist exclusion and ethnic conflict: shadows of modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

Wimmer, A. Nation building: a long-term perspective and global analysis. Eur Sociol Rev 2015;31(1):30–47.

Wimmer, A, Cederman L -E, Min B. Ethnic politics and armed conflict: a configurational analysis of a new global data set. Am Sociol Rev 2009;74(2):316–337.

Zuber, C I. Understanding the multinational game: toward a theory of asymmetrical federalism. Comp Pol Stud 2011;44(5):546–571.

Acknowledgments

For advice and comments, we thank Scott Abramson, Mark Beissinger, Michael Donnelly, Evan Lieberman, Rebecca Littman, John Londregan, Brandon Miller de la Cuesta, Betsy Levy Paluck and Marc Ratkovic. Two anonymous reviewers provided very detailed and valuable comments. We also thank seminar participants at Princeton University and at the annual meetings of the American Political Science Association and the Midwest Political Science Association. Ricart-Huguet is grateful to Helen Milner, Daniel Nielson and Mike Findley for their support during fieldwork.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ricart-Huguet, J., Green, E. Taking it Personally: the Effect of Ethnic Attachment on Preferences for Regionalism. St Comp Int Dev 53, 67–89 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-017-9240-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-017-9240-3

T

i

|X

i

∀t ∈ T. The method ensures that for a variable T, at least with respect to observables, we have that Y

i

(t) ⊥ ⊥ T

i

|X

i

∀t ∈ T.

T

i

|X

i

∀t ∈ T. The method ensures that for a variable T, at least with respect to observables, we have that Y

i

(t) ⊥ ⊥ T

i

|X

i

∀t ∈ T.