Abstract

There is a growing consensus in the literature that the occurrence of political budget cycles (PBCs) is highly conditional upon context. Most studies have focused on incumbents’ abilities to engage in pre-electoral fiscal manipulation while neglecting their incentives. This is particularly true for studies outside the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which have attributed to incumbents a uniform and constant motivation to manipulate budgets in order to win elections. We argue that this is not the case. Using new data on state spending from 1960 to 2006 for 76 non-OECD countries, we show that PBCs primarily occur under conditions of uncertain electoral prospects. Thus, incentives to manipulate public spending prior to elections vary according to the incumbent’s electoral confidence. Given the particular context of non-OECD countries, we argue theoretically and show empirically that incumbents’ electoral confidence primarily depends on the tightness of past electoral results. Past political competition is thus a key driver of fiscal behavior in non-OECD countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

29 May 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-023-09397-w

Notes

Following Alt and Rose (2009, p. 845), we define PBCs as “regular, periodic fluctuation in a government’s fiscal policies induced by the cycle of elections.”

We exclude all countries that are currently members of the OECD from the analysis. The group of countries we analyze is thus not entirely commensurate, yet certainly overlapping to a large extent, with economically less developed countries.

It is generally agreed that PBCs are stronger in spending than in revenues (Alt and Rose 2009). Thus, if we do not find PBCs in spending, it is unlikely that we will find PBCs in revenues.

We consider PBCs, patronage, and vote-buying distinct phenomena (with corresponding distinct bodies of literature) but recognize that they intersect when patronage and vote-buying is government funded. Our analysis captures only this intersection. Whether budget increases are used to fund public goods (roads, schools, hospitals, etc.) or private goods (wages, pensions, jobs, etc.) is a question of budget allocation, which we do not analyze in this paper.

Persson and Tabellini (2003) argue that in parliamentary systems, incumbents control both the executive and the legislature, making it easier to push through budgets and public accounts. Franzese (2002) argues that the separation of powers that characterizes presidential systems prevent incumbents from manipulating public spending.

Schultz (1995) suggests that the effect is positive and linear (unpopular governments boost public spending, as they fear losing elections; popular governments do not), while Price (1998) argues that it is bell-shaped (very unpopular governments also do not boost public spending as the costs of hiking up spending to the required level outweigh the benefits of being re-elected).

First surveys occurred in the USA (1936), the UK (1937), and France (1938), followed by Australia, Canada, Denmark, Switzerland, the Netherlands, West Germany, Finland, Norway, and Italy by 1946 (see Worcester 1989).

In a survey conducted by the University of Maryland just before the elections, Amr Moussa was predicted to obtain 28 % (obtained 11.13 %), and Abdel Moneim Abdel Fotouh was given 32 % (obtained 17.47 %).

Particularly problematic are restrictions that forbid the publication of polls prior to elections. These blackout periods vary from 1 day to up to 4 weeks in some countries. According to the World Association for Public Opinion Research (WAPOR), pre-election restrictions have increased, and in 2012, virtually, every other country reported the existence of blackout periods before elections (Chung 2012). This means that even if pre-election polls exist, incumbents might be unable to access the information that would allow them to gauge their re-election prospects.

Correlation between both data sources is still high, generally in the area of 0.70 and above. This implies that both datasets can be used interchangeably for periods past 1972.

The three properties are coded in Hyde and Marinov (2011).

In the classification scheme proposed by Marshall and Jaggers (2010), the polity threshold of −6 separates autocracies from hybrid regimes.

In practice, this means that we do not consider parliamentary elections in presidential political systems. To select politically important elections, we combine data from the Arthur Banks Dataset (2011) on the type and the mode of selection of the chief executive.

Since there is no literature on cross-country predictors of survey accuracy, we selected our predictors inductively, bearing in mind theoretical plausibility and a high predictive power as measured by R 2. The final R 2 was quite satisfactory with 49 % of the error predicted by our model. Details on the model including a full list of variables are available in the Online Appendix (Table A3).

This binary indicator combines information from two variables in the NELDA dataset, namely, Nelda 25 and Nelda 26.

However, a stumbling economy might considerably limit the incumbent’s capacity to engage in discretionary fiscal policies, making the latter scenario somewhat unlikely.

A summary statistic of our variables, as well as a list of all included countries is available in the Online Appendix (Tables A1 and A2).

An Arellano-Bond test suggests the inclusion of three lags to remove all serial correlation in the error term.

A Hausman test suggests the use of country fixed effects.

Panel-specific heteroskedasticity was detected using a modified Wald test.

The bias amounts to 1/T.

In the Online Appendix, we run an alternative model with a continuous measure of electoral confidence, carried forward from the last elections (Table A8). The substantive findings of this paper remain robust to this model adjustment.

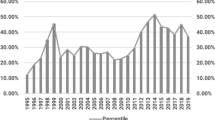

This graph follows the suggestions of Berry et al. (2012).

The scale for the effect on the budget balance can be found on the left y axis.

The scale for the histogram can be found on the right y axis.

To be precise, we should see this effect in 95 % of our cases.

As the survey indicator is not available for all countries in the sample, we lose 225 observations and three countries when adding the variable.

These additional control variables are not included in our base model as they are considered less important in the literature and are therefore rarely included in standard models of PBCs.

Recall that we exclude elections where no opposition was allowed, where only one party was legal, or where there was no choice of candidates on the ballot. Effectively, Party ban therefore becomes a three-point scale, ranging from “yes, many parties are banned” to “no, no parties are officially banned.”

References

Aidt T, Veiga FJ, Veiga LG. Election results and opportunistic policies: a new test of the rational political business cycle model. Public Choice. 2011;148(1-2):21–44.

Akhmedov A, Zhuravskaya E. Opportunistic political cycles: test in a young democracy setting. Q J Econ. 2004;119(4):1301–38.

Alesina A. Macroeconomic policy in a two-party system as a repeated game. Q J Econ. 1987;102(3):651–78.

Alesina A, Cohen G, Roubini N. Macroeconomic policies and elections in OECD democracies. Econ Polit. 1992;4(1):1–30.

Alesina A, Cohen G, Roubini N. Electoral business cycle in industrial democracies. Eur J Polit Econ. 1993;9(1):1–23.

Alesina A, Cohen G, Roubini N. Political cycles and the macroeconomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997.

Alt JE, Lassen DD. Transparency, political polarization, and political budget cycles in OECD countries. Am J Polit Sci. 2006;50(3):530–50.

Alt JE, Rose SS. Context-conditional political budget cycles. In: Boix C, Stokes SC, editors. The Oxford handbook of comparative politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 845–67.

Banks A. Cross-National Time Series Data Archive [Dataset]. 2011 Retrieved June 13, 2016. www.databanksinternational.com

Beck NL, Katz JN. Modeling dynamics in time-series-cross-section political economy data. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2011;14:331–52.

Berry WD, Golder M, Milton D. Improving tests of theories positing interaction. J Polit. 2012;74(3):653–71.

Block SA. Political business cycles, democratization, and economic reform: the case of Africa. J Dev Econ. 2002;67(1):205–28.

Block SA, Ferree KE, Singh S. Multiparty competition, founding elections and political business cycles in Africa. J Afr Econ. 2003;12(3):444–68.

Brender A, Drazen A. Political budget cycles in new versus established democracies. J Monet Econ. 2005;52(7):1271–95.

Brender A, Drazen A. Electoral fiscal policy in new, old, and fragile democracies. Comp Econ Stud. 2007;49:446–66.

Carr A. Psephos. 2013. http://psephos.adam-carr.net/: (accessed 10 Feb 2016)

Center of Democratic Performance. Election Results Archive. 2012. http://www.binghamton.edu/cdp/era15.html (accessed: 10 Feb 2016).

Chowdhury A. Political surfing over economic waves: parliamentary election timing in India. Am J Polit Sci. 1993;37:1100–18.

Chung R. The freedom to publish opinion poll results. Hong Kong: World Association for Public Opinion Research and University of Hong Kong; 2012.

Coppedge M, Gerring J, Lindberg S I, Skaaning S-E, Teorell J, Altman D, … Zimmerman, B. V-Dem Country-Year Dataset v5. 2015. https://www.v-dem.net (accessed: 10 Feb 2016)

Crespi I. Public opinion, polls, and democracy. London: Westview; 1989.

Dreher A. IMF and economic growth: the effects of programs, loans, and compliance with conditionality. World Dev. 2006;34:769–88.

Efthyvoulou G. Political budget cycles in the European Union and the impact of political pressures. Public Choice. 2011;153(3-4):295–327.

Franzese RJ. Electoral and partisan cycles in economic policies and outcomes. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2002;5:369–421.

Gibney M. Cornett L. Reed W, Haschke P, Arnon D. The Political Terror Scale 1976-2015. 2015. http://www.politicalterrorscale.org (accessed: 10 Feb 2016)

Goemans HE, Gleditsch KS, Chiozza G. Introducing Archigos: a dataset of political leaders. J Peace Res. 2009;46(2):183–269.

Haber S, Menaldo V. Do natural resources fuel authoritarianism? A reappraisal of the resource curse. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2011;105(1):1–26.

Heath A, Fisher S, Smith S. The globalization of public opinion research. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2005;8(1):297–333.

Heston A, Summers R, Aten B. 2006. Penn World Table version 6.2. http://cid.econ.ucdavis.edu/pwt.html (accessed: 10 Feb 2016)

Hibbs DA. Political parties and macroeconomic policy. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1977;71(04):1467–87.

Hibbs DA. Political-economic cycles. In: Weingast B, Wittman D, editors. The Oxford handbook of political economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 565–86.

Hyde SD, Marinov N. Which elections can be lost? Polit Anal. 2011;49(4):503–16.

Hyde SD, O’Mahony A. International scrutiny and pre-electoral fiscal manipulation in developing countries. J Polit. 2010;72(3):690–704.

Ito T. The timing of elections and political business cycles in Japan. J Asian Econ. 1990;1:135–56.

Jeffries R, Thomas C. The Ghanaian elections of 1992. Afr Aff. 1993;92(368):331–66.

Kayser MA. Who surfs, who manipulates? The determinants of opportunistic election timing and electorally motivated economic intervention. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2005;99(1):17–27.

Klomp J, De Haan J. Political budget cycles and election outcomes. Public Choice. 2012;157(1-2):245–67.

Krause GA. Voters, information heterogeneity, and the dynamics of aggregate economic expectations. Am J Polit Sci. 1997;41(4):1170–200.

Larmer M, Fraser A. Of cabbages and King Cobra: populist politics and Zambia’s 2006 election. Afr Aff. 2007;106(425):611–37.

Lucas V, Richter T. State hydrocarbon rents, authoritarian survival and the onset of democracy: evidence from a new dataset. Res Polit. 2016;3(3). doi:10.1177/2053168016666110

Marshall M G, Jaggers K. Polity IV Annual time-series 1800-2010. 2010. http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html (accessed: 10 Feb 2016)

Marshall MG, Gurr TR, Jaggers K. Polity IV project: dataset users’ manual. Arlington: VA/Severn; 2010.

Nickell S. Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica 1981;49(6):1417–1426.

Persson T, Tabellini G. Do electoral cycles differ across political systems? Working Paper No. 232, Innocenzo Gasparini Institute for Economic Research (IGIER). 2003; Bocconi University: Milan.

Petterson-Lidbom P. An empirical investigation of the strategic use of debt. J Polit Econ. 2001;109(3):570–83.

Price S. Comment on “The politics of the political business cycle.”. Br J Polit Sci. 1998;28(1):201–10.

RCP. Real Clear Politics. 2013. Retrieved from http://www.realclearpolitics.com (accessed: 15 May 2015).

Rogoff K. Equilibrium political budget cycles. Am Econ Rev. 1990;80(1):21–36.

Schedler A. The menu of manipulation. J Democr. 2002;13(2):36–50.

Schneider C. Fighting with one hand tied behind the back: political budget cycles in the West German States. Public Choice. 2010;142:125–50.

Schuknecht L. Political business cycles and fiscal policies in developing countries. Kyklos. 1996;49(2):155–70.

Schuknecht L. Fiscal policy cycles and the exchange rate regime in developing countries. Eur J Polit Econ. 1999;15(3):569–80.

Schultz KA. The politics of the political business cycle. Br J Polit Sci. 1995;25(1):79–99.

Shelton CA. Legislative budget cycles. Public Choice. 2014;159(1):251–75.

Shi M, Svensson J. Political budget cycles: do they differ across countries and why? J Public Econ. 2006;90(8-9):1367–89.

Vergne C. Democracy, elections and allocation of public expenditures in developing countries. Eur J Polit Econ. 2009;25(1):63–77.

Worcester R. The internationalization of public opinion research. Pub Opin Q. 1989;51(2):79–85.

World Bank. Database of political institutions 2012. 2013. http://econ.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/EXTDEC/EXTRESEARCH/0,,contentMDK:20649465~pagePK:64214825~piPK:64214943~theSitePK:469382,00.html (accessed: 10 Feb 2013).

World Bank. World development indicators. 2010. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=wdi-database-archives-(beta) (accessed: 10 Feb 2016)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 51 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eibl, F., Lynge, H. Electoral Confidence and Political Budget Cycles in Non-OECD Countries. St Comp Int Dev 52, 45–63 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-016-9230-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-016-9230-x