Abstract

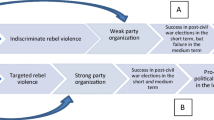

Over the last several decades, numerous civil wars have ended as a consequence of negotiated settlements. Following many of these settlements, rebel groups have made the transition to political party and competed in democratic elections. In this paper, I assess the legacy of civil war on the performance of rebel groups as political parties. I argue that the ability of rebels to capture and control territory and their use of violence against the civilian population are two key factors explaining the performance of rebels as political parties. I test these hypotheses against the case of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) in El Salvador using one-way ANOVA and multivariate regression analyses. In analyzing the FMLN’s performance in the 1994 “elections of the century,” I find that, as a political party, the FMLN benefited both from the state’s violently disproportionate response and its ability to hold territory during the war.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These elections have been referred to as the “elections of the century” because, in addition to being the first election in the postwar period, it was the first time since the adoption of the 1983 constitution that the election for each level of government was held simultaneously. Elections for the presidency are held every 5 years while those for legislative and municipal office every three.

Since the signing of the Peace Accords in 1992, the FMLN has competed in four presidential elections (1994, 1999, 2004, and 2009) and six legislative and municipal elections (1994, 1997, 2000, 2003, 2006, and 2009).

Alvarez cites an undated document, El Poder Popular en El Salvador, by J. Ventura(e) as the source of FMLN activity.

In addition, McClintock supplements these municipalities with others where elections were held, but the mayor was forced to govern in exile because of the presence of the FMLN.

Future studies are encouraged to refine the operationalization of FMLN-controlled zones. First, more extensive research might systematically divide these two categories to further distinguish between FMLN controlled territory and “zones of FMLN operation.” The degree to which the FMLN controlled these 59 zones varied significantly as did the length of time over which the FMLN operated in these municipalities.

During the initial coding of the municipalities most severely affected by the civil war, ten municipalities were not coded because they were too dangerous. In the following analyses, I have coded these ten as conflict zones. I ran the analyses with and without these ten municipalities as ex-conflict zones. There were no differences in the results.

Ministerio de Economía, Dirección General de Estadística y Censos. Encuesta de Hogares de Propositos Multiples, 1998.

The FMLN won 13 municipal elections by itself and two in an alliance with the CD.

While the FMLN was guilty of assassinating civilian government officials and engaging in sporadic forced recruitment, there is no credible evidence that the FMLN participated in large-scale attacks against the civilian population. One might make the argument, that had the FMLN captured state power, it would have ruled with an iron fist and through the use of terrorism, but there is little evidence that during the war the FMLN controlled the population within its sphere of influence through violence.

I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for further refining this expectation.

In the 1984 elections, the FMLN prevented elections from being held in 59 municipalities. San Luis de la Reina in San Miguel drops from all analyses, though, because there is no available electoral data from 1994. San Luis would have counted as an FMLN controlled zone and conflict zone.

Readers should be aware that Brian J. Bosch is a former U.S. military attaché whose analysis of the civil war in El Salvador is self-described as “principally from the San Salvador government’s perspective” (1999: xi), José Angel Moroni Bracamonte is the “pen name of a combatant in the war” on the Salvadoran military’s side, and David E. Spencer served in the U.S. Army and National Guard while working as a political consultant to the armed forces.

One possible explanation, of course, is that the FMLN was responsible for more of the deaths in these areas than the government. Unfortunately, at this point, I am unable to distinguish between the two.

References

Allison ME. The transition from armed opposition to electoral opposition in Central America. Lat Am Pol Soc. 2006;48:137–62.

Alvarez FA. Transition before the transition: the case of El Salvador. Lat Am Persp. 1988;15:78–92.

Baloyra-Herp EA. Elections, civil war, and transition in El Salvador, 1982–1994: A preliminary evaluation. In: Seligson MA, Booth JA, editors. Elections and democracy in Central America revisited. NC: University of North Carolina Press; 1995. p. 45–65.

Bosch BJ. The Salvadoran Officer Corps and the Final Offensive of 1981. NC: McFarland; 1999.

Bracamonte JAM, Spencer DE. Strategy and tactics of Salvadoran FMLN Guerrillas: last battle of the cold war, blueprint for future conflicts. CT: Praeger; 1995.

Deonandan K, Close D, Prevost G (Eds) From revolutionary movements to political parties. NY: Palgrave MacMillan; 2007.

Department of Social Science Universidad de El Salvador. An analysis of the correlation of forces in El Salvador. Lat Am Persp. 1987;14:426–52.

de Zeeuw, J, (ed) From soldiers to politicians: Transforming rebel movements after civil war. CO: Rienner; 2007.

Fearon JD, Laitin DD. Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. Am Pol Sci Rev. 2003;97:75–90.

Hammond JL. Fighting to learn: popular education and Guerrilla war in El Salvador. NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1998.

Hauss C, Rayside D. The development of new parties in western democracies since 1945. In: Maisel L, Cooper J, editors. Political parties: development and decay. CA: Sage Publications; 1978. p. 31–57.

Herman ES, Brodhead F. Demonstration elections: US-staged elections in the Dominican Republic, Vietnam, and El Salvador. MA: South End; 1984.

Kalyvas SN. Wanton and senseless? The logic of massacres in Algeria. Rationality and Society. 1999;11:243–85.

Kalyvas SN. ‘New’ and ‘old’ civil wars: a valid distinction? World Politics. 2001;54:99–118.

Kumar K. Postconflict elections, democratization & international assistance. CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc; 1998.

Lewis P. Political parties in post-communist eastern Europe. NY: Routledge; 2000.

Lewis-Beck M, Stegmaeir M. Economic determinants of electoral outcomes. An Rev Pol Sci. 2000;3:183–219.

Licklider R. The consequences of negotiated settlements in civil wars, 1945–1993. Am Pol Sci Rev. 1995;89:681–90.

Luciak IA. After the revolution: gender and democracy in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2001.

Manning C. Armed opposition groups into political parties: comparing Bosnia, Kosovo, and Mozambique. Stud Comp In Dev. 2004;39:54–76.

McClintock C. Revolutionary movements in Latin America: El Salvador’s FMLN and Peru’s shining path. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press; 1998.

Pearce J. Promised land: peasant rebellion in Chalatenango, El Salvador. London: Latin American Bureau; 1984.

Seligson MA, McElhinny V. Low-intensity warfare, high-intensity death: the demographic impact of the wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua. Can J Lat Am Can Stud. 1996;21:211–41.

Shugart MS. Guerrillas and elections: an institutionalist perspective on the costs of conflict and cooperation. Int Stud Quart. 1992;36:121–52.

Spence J, Vickers G. Toward a level playing field? A report on the post-war Salvadoran electoral process. MA: Hemisphere Initiatives; 1994.

Stahler-Stolk R. El Salvador’s negotiated transition, from low intensity conflict to low intensity democracy. Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 1995;19:1–53.

Tucker JA. The first decade of post-communist elections and voting: what have we studied, and how have we studied it? Ann Rev Pol Sci. 2002;5:271–304.

Vickers G, Spence J. Elections: the right consolidates power. NACLA Rep Amer. 1994;18:1–15.

Wantchekon L. Strategic voting in conditions of political instability: the 1994 elections in El Salvador. Comp Pol Stud. 1999;32:810–34.

Wickham-Crowley TP. Winners, losers, and also-rans: Toward a comparative sociology of Latin American Guerrilla movements. In: Eckstein S, editor. Power and popular protest. CA: UC Press; 1990. p. 132–81.

Wickham-Crowley TP. Guerrillas and revolution in Latin America: a comparative study of rebels and regimes since 1956. NJ: Princeton Univ. Press; 1992.

Wood EJ. Forging democracy from below: rebel transitions in South Africa and El Salvador. NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Wood EJ. Rebel collective action and civil war in El Salvador. NY: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Paul Hensel, Christina Fattore, Joe Young, Stephen Shellman, Len Champney, William Parente, and the editors and anonymous reviewers of Studies in Comparative International Development for their constructive and helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allison, M.E. The Legacy of Violence on Post-Civil War Elections: The Case of El Salvador. St Comp Int Dev 45, 104–124 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-009-9056-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-009-9056-x