Abstract

Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), characterized as excess lipid accumulation in the liver which is not due to alcohol use, has emerged as one of the major health problems around the world. The dysregulated lipid metabolism creates a lipotoxic environment which promotes the development of NAFLD, especially the progression from simple steatosis (NAFL) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Purposeand Aim

This review focuses on the mechanisms of lipid accumulation in the liver, with an emphasis on the metabolic fate of free fatty acids (FFAs) in NAFLD and presents an update on the relevant cellular processes/mechanisms that are involved in lipotoxicity. The changes in the levels of various lipid species that result from the imbalance between lipolysis/lipid uptake/lipogenesis and lipid oxidation/secretion can cause organellar dysfunction, e.g. ER stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, lysosomal dysfunction, JNK activation, secretion of extracellular vesicles (EVs) and aggravate (or be exacerbated by) hypoxia which ultimately lead to cell death. The aim of this review is to provide an overview of how abnormal lipid metabolism leads to lipotoxicity and the cellular mechanisms of lipotoxicity in the context of NAFLD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In line with the global epidemic of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is increasing throughout the world. Recently, a new definition of NAFLD was suggested by a panel of international experts: Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD), which contains “positive criteria” and is independent of alcohol use to diagnose the disease [1]. However, considering that the majority of studies referred to in this review were based on criteria of NAFLD, we decided to use the nomenclature of NAFLD in the current review. NAFLD is the most common liver disorder in Western countries with a prevalence of approximately 25% [2]. It is characterized by excessive hepatic lipid deposition (steatosis) in the absence of excessive alcohol use or alternative causes. The spectrum of NAFLD ranges from simple steatosis (NAFL) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis and ultimately cirrhosis with its known complications, such as decompensation and/or hepatocellular carcinoma [3]. From 2003 to 2014 NASH was the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in the United States [4]. In the near future, NASH will become the leading indication for liver transplantation [5].

NAFLD is recognized as the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Abundant data link NAFLD with abdominal obesity, T2DM, hypertension and atherogenic dyslipidemia which are risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [6, 7]. Mortality in patients with NAFLD is mainly attributed to increased risk of death due to CVD and liver-related death. Fibrosis stage predicted both overall and disease-specific mortality [8].

From a clinical point of view, the full understanding of the mechanisms underlying the development of NAFLD and NASH is of extreme importance to treat the hepatic and extrahepatic complications of NAFLD. It is now generally recognized that the development of NAFLD is a multifactorial process. Apart from obesity and T2DM, which are two important factors commonly associated with NAFLD, environmental and genetic factors, as well as gut microbiota, are likely to play a role in the onset and progression of NAFLD [3, 9, 10]. A thorough discussion of the role of microbiota and NAFLD is outside the scope of this review and has been reviewed recently [11]. Thus, both the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to disease and the clinical manifestations are highly heterogeneous. Hepatic steatosis results from an imbalance between synthesis and utilization of lipids. Dysregulation of lipid homeostasis in hepatocytes leads to the generation of toxic lipids that result in dysfunctional organelles promoting inflammation, hepatocellular damage and cell demise [8]. Elucidating the pathways leading to lipotoxicity-induced cell injury may lead to the development of new therapeutic options. Thus, the various pathways involved in hepatic fat accumulation and lipid toxicity contributing to the pathogenesis of NAFLD and eventually end-stage liver disease are discussed below.

Metabolic changes of lipids in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Lipolysis of adipose tissue

Most NAFLD patients have increased white adipose tissue (WAT) mass and its expansion is a high-risk factor in the progression of NAFLD [12, 13]. Human studies have shown that the shift of fat storage from subcutaneous to visceral adipose tissue is associated with liver damage [12, 14] and the expansion of visceral adipose tissue may be a powerful predictor for NAFLD. Nonetheless, determining whether the liver damage is associated with the changes in the fatty acid composition of adipose tissues needs more study [15].

As the main source of circulating lipids, the increased secretion of FFAs from adipose tissue is strongly associated with enhanced lipolysis, in particular increased triglyceride (TG) hydrolysis. Obese NAFLD patients demonstrated greater lipolysis in adipose tissue, which may account for 60–70% of fat accumulating in the liver [16]. The excessive lipolysis of adipose tissue is accompanied with abnormal production of hormones released by adipocytes (e.g. reduced production of adiponectin) and adipose tissue inflammation (e.g. the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines), all of which participate in promoting insulin resistance (IR), thus further contributing to ectopic fat deposition [17, 18].

In addition to the cytosolic lipolysis, lipophagy is an alternative way of TG hydrolysis. As a form of autophagy, specifically macroautophagy, lipophagy mediates the hydrolysis of TG stored in lipid droplets via fusion of the engulfed droplets with lysosomes. Of note, the contribution of lipophagy to the catabolism of TG is more prominent in brown adipose tissue and the liver compared to WAT [19]. Moreover, NAFLD patients, subjected to chronic lipid exposure, exhibit an inhibited lipophagy, whereas an acute addition of lipids to cells in vitro may enhance lipophagy, which might be an adaptive response. In addition, FFAs derived from the efflux from other cell types, for example, hepatocytes, as well as FFAs released from TG-rich lipoproteins by lipoprotein lipase (LPL), are also sources of circulating FFAs (Fig. 1).

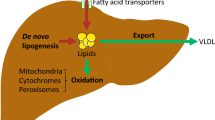

Hepatic lipid metabolism in NAFLD. Dietary lipids are mainly absorbed in the intestine and incorporated into intestinal chylomicrons (intestinal CMs) and then transported to adipose tissue and the liver via the bloodstream. In adipose tissue, intestinal CMs are taken up and stored in lipid droplet. In NAFLD, the hydrolysis of TG is largely enhanced in adipocytes. TG is hydrolyzed into diacylglycerol (DAG), monoacylglycerol (MAG) and glycerol, releasing one fatty acid in each step. The increased fatty acid load is then delivered to the liver, scavenged by fatty acid translocase (FAT/CD36), fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs) and caveolins and incorporated into lipid droplets. In hepatocytes, de novo lipogenesis is increased which contributes to the lipid pool as well. On the other hand, fatty acids are oxidized in mitochondria (mitochondrial β-oxidation), peroxisomes (peroxisomal β-oxidation) and microsomes (microsomal ω-oxidation), accompanied by an elevated production of ROS. The secretion of TG-enriched very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) is another route of lipid disposal. It is increased in absolute terms, but its increase does not match the increased fat accumulation in NAFLD. Arrows (red) indicate the up- or down-expressions of specific proteins in NAFLD. CPT1/2 carnitine palmitoyltransferase ½, FFA free fatty acid, TCA cycle: the citric acid cycle, ETC electron transport chain, FABP fatty acid-binding protein, ACC acetyl-CoA carboxylase, FAS fatty acid synthase, DGAT diacylglycerol acyltransferase, MGAT monoacylglycerol acyltransferase

Lipid uptake

In NAFLD patients, the uptake of circulating lipids, in particular FFAs and lipoproteins, by the liver is increased. This increased uptake is related to the enhanced level of lipid transport proteins in the plasma membrane, as well as increased levels of hepatic lipase and lipoprotein lipase (LPL) in response to IR [20, 21].

Fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs), caveolins and fatty acid translocase (FAT/CD36) are the main hepatic plasma membrane proteins that act as scavengers of lipids and contribute to the hepatic lipid pool. Among the FATP members, FATP2 and FATP5 are the main isoforms expressed in the liver. Silencing FATP2 or knockout of FATP5 led to reduced hepatic TG levels and resistance to diet-induced obesity in mice [9, 22]. On the other hand, NAFLD is associated with increased expression and translocation of caveolin-1, a protein functioning in cellular cholesterol transport [23]. Interestingly, caveolin-1 overexpression protected and caveolin-1 knockout aggravated hepatic steatosis in HFD-fed mice by affecting lipogenesis, which indicates regulatory functions of caveolin-1 other than lipid transport in the liver [24]. In NAFLD patients, the expression of FAT/CD36 is increased in the liver and correlated with hepatic apoptosis [9]. Moreover, hepatocyte-specific deletion of FAT/CD36 prevented fat accumulation in the liver and repressed inflammation [25]. Notably, in the liver, FAT/CD36 is highly expressed in non-parenchymal cells in comparison to hepatocytes, thus FAT/CD36 might play more important roles in hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis compared to lipid uptake. With regards to the role of lipases, loss-of-function studies on hepatic lipase and LPL in the liver showed that knockout of hepatic lipase resulted in increased hepatic steatosis and inflammation in mice fed a high-fat high-cholesterol diet that might be due to the activation of stress pathways like SAPK/JNK and p38 [26]. LPL is mainly expressed in non-parenchymal cells in the liver and is also involved in hepatic fibrogenesis [27].

In addition, hepatic FABPs facilitate the shuttling of fatty acids and their expression positively correlates with the progression of NAFLD. Different FABPs transfer fatty acids to phospholipid bilayers at different rates and via distinct kinetic mechanisms [28]. Furthermore, FABPs may also participate in other cellular processes, such as cell differentiation [28]. Thus, more studies are needed to elucidate their role in the progression of NAFLD.

De novo lipogenesis (DNL) and triglyceride synthesis

DNL is a cellular process that converts acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA into fatty acids. Several clinical studies indicated that the rate of DNL is increased and responsible for around 20–30% of fat accumulation in the liver in obese NAFLD patients [13, 16]. Mechanistically, the elevated DNL is closely associated with IR and excessive carbohydrate intake. IR hampers glucose oxidation and shuttles carbohydrates into the DNL pathway [20]. Of note, compared to glucose, fructose demonstrates a greater influence on activating DNL and fueling TG synthesis [29]. The elevated DNL is concomitant with increased de novo glycerolipid synthesis and subsequent TG accumulation, incorporating FFAs into TG and forming lipid droplets. Apart from facilitating TG synthesis, glycerolipid metabolism is a major process that produces a large number of lipid second messengers, including phosphatidic acid, lysophosphatidic acid, diacylglycerol (DAG), other lipid intermediates and related lipids (e.g. ceramides and various sphingolipids). These lipids have been linked to impaired insulin signaling and cytotoxic effects [30]. Although several lipidomics studies have shown that NAFLD patients demonstrated abnormal glycerolipid metabolism (summarized in 3.1), the underlying molecular mechanisms are still largely unclear.

Fatty acid oxidation (FAO)

Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) is roughly proportional to the concentration of plasma FFAs. Within cells, FFAs, either imported from plasma or released from intracellular lipids via cytosolic lipolysis or lipophagy, are mainly oxidized in mitochondria (mitochondrial β-oxidation), peroxisomes (peroxisomal β-oxidation) and microsomes (microsomal ω-oxidation). Although mitochondrial β-oxidation is one of the best-studied processes, contradictory results were reported in subjects with NAFLD. Since there is no direct measurement of mitochondrial oxidation available in vivo, indirect measures assessing plasma ketone body concentrations suggest that hepatic FAO could be either increased or decreased [13, 31]. Similarly, animal and human studies using stable isotopes showed increased, normal or decreased FAO [32,33,34]. Notably, the activities of all mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes were undisputedly decreased in the liver tissue of patients with NASH [34].

Besides mitochondria, fatty acids can also be oxidized in peroxisomes and microsomes. These two organelles are mainly responsible for the oxidation of very-long-chain fatty acids, branched-chain fatty acids and unsaturated fatty acids. Deficiency of peroxisomal enzymes [e.g. acyl-coenzyme A oxidase (Acox1) or peroxisomal biogenesis factor 11α (Pex11α)] resulted in impaired peroxisomal β-oxidation, increased lipid accumulation and exacerbated hepatocellular damage [35, 36], indicating the indispensable role of peroxisomes in lipid metabolism in the context of NAFLD. With respect to microsomal ω-oxidation, hepatic fatty acid overload acts both as a substrate and as an inducer of microsomal cytochrome P-450 family members. Together with mitochondria, peroxisomes and microsomes are important sources of ROS production.

Very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) excretion

Hepatic TG-enriched lipoprotein secretion is increased in absolute terms in NAFLD, but its increase does not match the increased fat accumulation in hepatocytes [13, 37]. Moreover, NASH patients demonstrated impaired synthesis and excretion of lipoproteins [13, 38], indicating that there is a limited capability of excretion of VLDL particles, which might be secondary to hepatocellular impairment [38, 39]. In addition, NAFLD patients showed increased production of small dense LDL, which is a risk factor of CVD [40].

VLDL is structured as a TG-enriched core with a monolayer of phospholipids and incorporating proteins like apolipoprotein B-100 facilitating VLDL delivery and uptake. Interestingly, it has been shown that the bulk of TG incorporated into lipoprotein VLDL is derived from exogenous lipids, but not from DNL [16, 37]. The impaired apolipoprotein B-100 synthesis in NASH patients could be related to the increased cellular FFA level, disturbed redox balance, hyperinsulinemia and decreased expression, all of which were shown to hamper apolipoprotein B-100 synthesis and VLDL assembly, thus resulting in lipid accumulation in the liver [39].

Mechanisms of lipotoxicity

Lipotoxicity, defined as the toxicity of lipids leading to organellar dysfunction, abnormal activation of intracellular signaling pathways, chronic inflammation and cell demise, is a hallmark of NASH [30, 41, 42]. The mechanisms of lipotoxicity involve several cellular processes, such as ER stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and lysosomal permeabilization, ultimately leading to cell death (apoptosis, necroptosis or pyroptosis). In recent years it has been shown that lipotoxicity may induce the release of extracellular vesicles (EVs) and affects (and is affected by) hypoxia, both of which play important roles in the progression of NAFLD (Fig. 2). The following paragraphs provide an update of the recent findings on the mechanisms of lipotoxicity in NAFLD.

Mechanisms of lipotoxicity in NAFLD. The mechanisms of lipotoxicity involve several cellular processes, such as ER stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, lysosomal dysfunction, the release of extracellular vesicles (EVs) and hypoxia, ultimately leading to cell death. Additionally, the activation of JNK signaling pathway also plays an important role in lipoapoptosis and its activation is closely associated with ER stress/UPR and mitochondrial dysfunction

Various lipid species are involved in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

One of the diagnostic criteria of NAFLD is “more than 5% (v/v) fat accumulation in the liver” on histology. However, not all lipids are toxic, e.g. TGs, which are considered as an inert lipid species, are recognized to be protective against toxic lipids. Moreover, several mono- or poly-unsaturated fatty acids [MUFAs and PUFAs, e.g. oleic acid, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)] demonstrate beneficial actions in NAFLD by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation and reducing lipid deposition [30]. Meanwhile, the toxic lipids, such as saturated fatty acids (SFAs), free cholesterol (FC), glycerophospholipids (GPLs) and sphingolipids, cause cellular injury and may promote cell death [30].

Our knowledge about the lipid species involved in NAFLD has substantially increased in the last decade. The unique lipid signatures across the entire disease spectrum have been revealed in NAFLD patients owing to the progression in lipidomics. The summary of the main lipidomics studies from liver biopsies and plasma samples of NAFLD patients are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Generally speaking, in the liver, there are increased levels of TG, diacylglycerol (DG) and FC in both NAFL and NASH patients, without substantial changes in the total FFA pool [43,44,45,46]. NASH patients showed higher amounts of short-chain FAs-, SFAs- and MUFAs-containing TG and lower amounts of PUFA-containing TG compared to control or NAFL subjects [43, 44, 46]. NASH was also associated with higher levels of sphingolipids and significantly decreased levels of arachidonic acid (AA) and AA-containing lipids [45, 46]. Regarding mitochondrial lipids, hepatic cardiolipin (CL) and ubiquinone are accumulated in NAFL and NASH, indicating increased mitochondrial oxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction. However, Puri et al. showed unaltered CL levels in the liver [43]. Furthermore, in cirrhotic patients, almost all lipids except eicosanoids and certain GPLs [e.g. phosphatidylinositols (PIs), ether-linked phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs)] were reduced compared to normal subjects [44].

Plasma from NAFL and NASH patients demonstrated a significant increase of TG, DG, MUFAs and SFAs, whereas a gradual decrease of total omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs content was observed across most lipid classes [FFAs, TG, phosphatidylcholine (PC) and lysophosphatidylcholine (LyPC)] [47, 48]. In these studies, contradictory results were observed with regard to several classes of phospholipids. E.g. sphingomyelin (SM) and PC/LyPC were reported to be either increased [49] or decreased [48] in NASH. Furthermore, cirrhotic patients demonstrated reduced plasma neutral lipids, GPLs and some sterols, but no reduction of FAs and several eicosanoids [44].

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress

As the main site of both lipid synthesis and protein folding and maturation, the ER is an important participant in the development of NAFLD. In the lipotoxic environment of NAFLD, many factors were shown to cause ER stress, including disrupted ER-to-Golgi protein trafficking, altered ER membrane composition and stiffness, impaired VLDL-TG assembly and the activation of intracellular signaling pathways [50]. Moreover, obese individuals demonstrate a decreased level of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2 (SERCA2) activity, which pumps the cytosolic Ca2+ into the ER lumen [51]. The change of Ca2+ gradient is another factor that is implicated in the occurrence of ER stress. ER stress triggers the activation of the UPR, which is initially destined to attenuate cellular stress. However, long-term non-attenuated ER stress promotes cellular injury via the apoptotic signaling pathways of the UPR.

In mammalian cells, the UPR is a highly conserved cellular signaling response, which is composed of three ER transmembrane proteins: inositol-requiring kinase 1α (IRE1α), double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK) and activating transcription factor-6α (ATF6α). Under normal conditions, these three sensors are maintained in an inactive state by binding to the ER chaperone protein glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78). Upon ER stress, GRP78 is released, allowing activation of PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6, and their downstream signaling pathways. Liver samples from NAFLD patients demonstrated the activation of the UPR, although there was a variable degree of UPR activation depending on the stages of the disease [50, 52]. Moreover, after caloric restriction, obese subjects showed weight loss together with ameliorated IR, reduced ER stress markers and improved mitochondrial function [53], suggesting the link between ER stress and abnormal lipid metabolism/IR.

Both in vivo and in vitro studies indicated that lipotoxicity is an important driver of ER stress in the context of NAFLD. Animals fed a diet enriched in saturated fat exhibited increased ER stress markers (e.g. X-box binding protein 1 (sXBP1) and GRP78) and liver injury, whereas diets with high unsaturated fat or starch did not induce ER stress or liver injury [30, 54]. In vitro studies demonstrated that hepatocytes challenged with several kinds of saturated fatty acids or lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) showed activation of the apoptotic UPR and subsequent cell death [55, 56] (Fig. 3). Mechanistically, the activation of apoptotic UPR by toxic lipids has been linked to several pro-apoptotic proteins. For example, C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) is one of the best-known pro-apoptotic proteins in response to ER stress. It regulates the expression of downstream BCL2 family proteins, causes Ca2+ release from ER and increases the expression of death receptor 5 (DR5) [50]. Meanwhile, the PERK/ATF3 pathway was shown to mediate palmitate-induced induction of the BH-3 only protein p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) and death protein 5 (DP5) [57]. Besides, IRE1 was demonstrated to orchestrate cell fate by controlling XBP1-mediated adaptive signaling and stimulating TRAF2/ASK1, subsequently activating JNK and p38 MAPK that promote apoptosis [50, 58]. In addition, the release of Ca2+ from the ER to the cytosol is another important player involved in the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway of apoptotic cell death [50, 59].

Lipotoxic UPR induces hepatic cell death. Under lipotoxic condition, several factors are implicated in the occurrence of ER stress, including disrupted ER-to-Golgi protein trafficking, altered ER membrane composition and stiffness, impaired VLDL-TG assembly and the change of Ca2+ gradient by the decreased level of SERCA2 activity. PERK is activated and leads to the phosphorylation of eIF2α, subsequently causes the activation of downstream ATF3- and CHOP-related apoptotic signaling pathways. IRE1α could also be activated by toxic lipids, thus stimulates TRAF2/ASK1/JNK signaling pathway. On the other hand, spliced XBP1 mediates adaptive UPR, which aims to alleviate ER stress. Together with apoptotic UPR, the massive efflux of Ca2+ from ER could result in mitochondrial dysfunction and the initiation of apoptotic cell death. VLDL very-low-density lipoprotein, SERCA2 sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2, ATF3 activating transcription factor 3, ASK1 apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1, CHOP C/EBP homologous protein, DR5 death receptor 5, DP5 death protein 5, eIF2α eukaryotic initiation factor 2α, TRAF2 TNF receptor-associated factor 2, IRE1α inositol-requiring kinase 1α, JNK c-Jun N-terminal kinase, PERK double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase-like ER kinase, PUMA p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis, sXBP1 spliced X-Box Binding Protein 1

Apart from regulating apoptotic cell death, the UPR also plays an important role in mediating lipid metabolism and IR. Among the UPR proteins, XBP1 is one of the most important regulators of lipogenesis and VLDL secretion, via directly and indirectly controlling the expression of critical genes involved in fatty acid synthesis [60]. PERK/ATF4 and ATF6 are also involved in hepatic steatosis. Genetic ablation of ATF4 resulted in hepatic steatosis in response to chemical induction of ER stress [61]. The nuclear form of ATF6α inhibits the transcriptional activity of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2) and blocking ATF6 inhibited hepatic mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation by decreasing the transcriptional activity of PPARα [62]. Under lipotoxic conditions, these regulatory pathways were disturbed. Lipotoxic ER stress also contributes to IR, which was mechanistically associated with the lipotoxic inhibition of IRE1α and its downstream transcription factor XBP1 via Bax inhibitor-1 (BI-1), an ER membrane protein [63]. Moreover, attenuation of palmitate-induced ER stress reduced IR and reversed the changes in insulin signaling pathways [64].

Mitochondrial dysfunction

As discussed previously in 2.3, even though the increased fatty acid flux and fatty acid uptake in the liver did not lead to clear alterations in mitochondrial β-oxidation, there is a consistent observation of mitochondrial dysfunction in NASH. Liver biopsies obtained from both NASH patients and rodent NAFLD models demonstrated defective mitochondrial respiratory chain function together with altered mitochondrial structure, presented as enlarged mitochondria, rounded cristae and loss of the typical dense mitochondrial granules, as well as an epigenetic modification on mitochondrial DNA [65, 66]. Compelling evidence shows that fatty acids (e.g. SFAs and ceramide) exhibit detrimental effects on mitochondrial function. Treatment with palmitic acid leads to a doubling in oxygen uptake rate at early stage and overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which causes oxidative modification of proteins and lipids and/or disrupts signaling pathways via inactivation of phosphatases [67]. It also induces the release of mitochondrial DNA from cells [68]. Moreover, palmitic acid-induced activation of JNK is related to the mitochondrial protein Sab (Sh3bp5) [69]. FFAs also indirectly cause mitochondrial injury by inducing lysosomal permeabilization, which causes activation of pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family that subsequently induce mitochondrial permeabilization and apoptotic cell death [70, 71].

Lysosomal dysfunction and impaired autophagy

Lysosomal dysfunction is described as reduced lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) activity, disturbed lysosomal acidification and lysosomal permeabilization and has been reported in NAFLD. LAL, hydrolyzing cholesteryl esters and TGs in lysosomes, play a role in lipid metabolism as well as in cell death in a caspase-dependent or -independent way. Clinical studies have shown that both the hepatic and serum LAL activity are reduced in NAFLD patients [72, 73]. Another study reported that in pediatric patients with NAFLD, the reduced serum LAL activity correlates with the severity of NAFLD-induced liver fibrosis but not with NAFLD [74], indicating its association with liver injury. Moreover, a case study highlighted the importance of considering LAL in the differential diagnosis of NAFLD, as its deficiency may cause a failure of treatment even when the patient achieves weight reduction [75].

Lysosomal acidification is disturbed in NAFLD patients, as demonstrated by the decreased number of acidic organelles by acridine orange staining and reduced level of mature cathepsin D [76]. Interestingly, lysosomal acidity has been shown to be mainly affected by exogenous but not endogenous fatty acids [77]. Exogenous fatty acids induce the redistribution of cathepsin B into the cytoplasm via promoting the translocation of Bax to lysosomes [71, 78]. Moreover, FFA-induced lysosomal permeabilization could lead to mitochondrial dysfunction since both pharmaceutical and genetic inhibition of cathepsin B preserved mitochondrial function, demonstrating the role of lysosomes in the initiation of the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis [70, 71].

Moreover, autophagy is impaired in NASH, which is associated with defective autophagosome formation and reduced lysosomal acidification [76]. Toxic fatty acids inhibit autophagic flux, which can lead to reduced mitophagy, reduced lipophagy, concomitant ER stress and oxidative stress, aggravating subcellular dysfunction [79]. On the other hand, these subcellular responses also affect autophagy, e.g. the activated UPR impairs selective autophagy by inhibiting autophagosome–lysosome fusion [80]. Promoting autophagy is considered as a therapeutic strategy in the treatment of NAFLD, however, a cell-specific outcome needs to be noted [79, 81].

JNK activation

As described above, JNK, a classic molecular regulator of cellular injury, can be activated by mitochondrial proteins, UPR signaling and ROS production in NASH. The accumulation of toxic lipids may cause sustained activation of JNK via ROS and MAP3K activation, while inhibition of JNK attenuates FFA-induced lipoapoptosis [69]. Noteworthy, the detrimental effects of JNK are mostly attributed to the JNK1 isoform. Investigations on the role of the JNK2 isoform suggest that JNK2 could be protective against cell injury [82, 83]. Evidence also exists for the central role of JNK in obesity and IR. The absence of JNK1 results in reduced obesity and improved IR [83]. These effects may be associated with the increased expression of PPARα target genes [69].

Mode of cell death involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD

Hepatic cell death is a common characteristic and an important driver in the progression of NASH, as well as the end-point outcome of lipotoxicity (Fig. 4). Several modes of cell death (apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis) have been described in NASH and linked to lipotoxicity-induced cell death. Evidence for all modes of cell death have been presented, but it is still a matter of debate which form of cell death is predominant in the context of NAFLD. The evidence for apoptotic cell death is based on positive TUNEL staining and immunohistochemistry for (cleaved) caspase 3/7 in liver biopsies as well as increased plasma levels of the cytokeratin-18 fragment and soluble Fas from NASH patients (but not from patients with simple steatosis). Lipotoxicity resulting in apoptosis has been termed lipoapoptosis and involves both the intrinsic or mitochondrial/lysosomal pathway as well as the extrinsic or death receptor pathway. The activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway is closely associated with the above mentioned subcellular dysfunctions (ER stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, lysosomal dysfunction and JNK activation) and includes the activation of caspase 2, an initiator caspase. Caspase-2 was markedly upregulated in injured hepatocytes in NASH patients and knockout of caspase 2 ameliorated steatohepatitis in mice [84, 85]. Furthermore, lipoapoptosis also involves the activation of caspase 2 [86]. In contrast, the expression of caspase-9 was shown to be reduced in ballooned hepatocytes in NASH specimens, which was explained by increased hedgehog signaling to prevent ballooned hepatocytes from death [87]. On the other hand, several extrinsic apoptotic receptors (death receptor 5, Fas receptor and TNF-R1) are significantly increased in liver samples from patients and animal models of NASH [88]. Steatotic hepatocytes demonstrated increased sensitivity to TRAIL- or Fas-mediated cell death. Genetic deletion of TRAIL receptor suppressed steatohepatitis and hepatic apoptosis [88, 89].

Modes of cell death in NASH. Apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis have all been described in NASH. Apoptosis, which can be demonstrated by caspase 3/7 activation, is triggered through both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways in NASH. Lysosomal dysfunction and ER stress are involved in the initiation of intrinsic pathway. In addition, caspase 2 is increased in NASH, whereas caspase 9 level is reduced in ballooned hepatocytes. In the extrinsic pathway, death receptor 5, apoptosis antigen 1 (Fas) and tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNF-R1) are increased in NASH leading to activation of caspase 8 and induction of apoptosis. Necroptosis is characterized as a mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL) related pore formation in the plasma membrane. It is induced by Receptor-Interacting Protein 3 (RIP3) and RIP1. Caspase 8 inhibits RIP3 activation. Pyroptosis is characterized as gasdermin D (GSDMD) mediated pore formation in the plasma membrane. Its activation is accompanied by inflammasome formation, which involves the maturation of caspase 1, IL-1β and NLRP3. Arrows (red) indicate the up- or down-expressions of specific proteins in NAFLD. IL-1β interleukin-1β, NLRP3 NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3

Several recent studies emphasized the role of necroptosis in the pathogenesis of NASH [90,91,92]. Both the regulatory factor RIP3 and the execution factor MLKL of necroptosis are expressed at low levels in the normal liver [93], NASH patients and dietary NASH mouse models demonstrated increased expression of RIP3 in the liver and elevated levels of RIP1 and MLKL in the serum [94, 95]. Moreover, inhibition of RIP1 by a specific RIP1 inhibitor protected against HFD-induced hepatic steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis in mice [95]. Deletion of RIP3 induced a shift from necroptosis to apoptosis in a HFD-mouse model, correlating with increased inflammation and hepatocyte apoptosis, as well as an early fibrotic response. In our studies, we observed that palmitic acid alone induced necrosis rather than apoptosis in primary rat hepatocytes [96], supporting a major role for necroptotic cell death. Moreover, inhibition of RIP1 with necrostatin-1 or siRNA knockdown of RIP3 reduced palmitic acid-induced cytotoxicity in vitro [97]. Therefore, lipotoxicity may not directly induce lipoapoptosis in primary hepatocytes.

Pyroptosis has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of NASH. Pyroptosis involves the activation of caspase-1 by the inflammasome multi-protein complex resulting in the activation of several pro-inflammatory cytokines and the cleavage of gasdermin proteins, which mediate pore formation in the plasma membrane and ultimately result in cell death. Liver samples of NASH patients and rodent models of NASH showed increased expression of caspase 1, gasdermin D (GSDMD) and inflammasome components compared to the simple steatosis stage [98, 99]. Saturated fatty acids as well as ceramide, but not unsaturated fatty acids, were shown to increase the level of inflammasome components in several types of hematopoietic cells. Palmitic acid also increases mRNA expression of NLRP3 in hepatocytes and triggers the release of danger signals, which in turn activate the inflammasome and the release of IL-1β and TNFα from liver mononuclear cells [100]. These effects may be associated with impaired mitophagy [101]. Furthermore, palmitic acid and LPS showed synergy in activating caspase 1 in hepatocytes [102]. In addition, it was proposed that pyroptosis might not only play a role in chronic inflammation but also in hepatic lipogenesis and fibrogenesis. Inhibition of caspase 1 or GSDMD ameliorated hepatic steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis in experimental NAFLD models [98]. In summary, available literature indicates that several modes of cell death (apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis) co-exist in the context of NAFLD. It is not possible to identify a dominant mode of cell death. The ‘mixed phenotype’ of cell death in the context of NASH has major implications for the selection of therapeutic targets.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs)

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are nano-sized vesicles that can be categorized into three subgroups: exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic bodies. As an important mode of intercellular communication, EVs play a critical role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and its actions in NAFLD were reviewed recently [103]. With regard to the increased secretion of EVs during the progression of NAFLD, experimental studies demonstrated that toxic lipids significantly increase the production of hepatocyte-derived EVs, which act as mediators of paracrine signaling, causing hepatic stellate cell activation, angiogenesis and activation of macrophages leading to inflammation and chemotaxis [103,104,105]. Mechanistically, the detrimental effects of EVs derived from toxic lipid-treated hepatocytes were attributed to miRNAs, proteins and lipids transported by EVs, e.g., miR-128-3p, inflammasome components, and C–X–C motif ligand 10 (CXCL10) [103].

The production of EVs is a regulated process. Palmitic acid-induced release of EVs was associated with the activation of the IRE1α/XBP-1 signaling pathway [106]. Meanwhile, the release of CXCL10-bearing EVs from hepatocytes was induced by mixed-lineage protein kinase 3 (MLK3) activation [107]. In addition, the inhibition of rho-associated protein kinase 1 (ROCK1) reduced the release of hepatocyte-derived EVs [104].

Hypoxia

Both clinical and experimental evidence show that the development of NAFLD is closely associated with hypoxia, which could be caused by e.g. obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) affecting 35–45% of obese individuals [108]. OSAS/hypoxia acts as a trigger for localized hepatic oxidative stress and inflammation that promotes the progression of NASH and hepatic fibrosis [109, 110]. Our recent studies revealed that hypoxia is an important factor that aggravates the toxic effects of lipids in hepatocytes. Hypoxic conditions elevated the inflammation in steatotic hepatocytes and increased the release of EVs derived from fat-laden hepatocytes, which stimulate the activation of hepatic stellate cells and the inflammatory phenotype in Kupffer cells [111, 112]. Vice versa, simple steatosis enhances the sensitivity of hepatocytes to hypoxic injury [113], though more detailed studies are needed. At the molecular level, the hypoxia signaling pathways are transcriptionally regulated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), which consist of three isoforms: HIF-1, HIF-2 and HIF-3. Both HIF-1α and HIF-2α have been shown to be associated with hepatic lipid metabolism, liver injury and the development of liver fibrosis [114, 115]. Therefore, hypoxia acts as a factor that worsens (or is exacerbated by) lipotoxicity and, importantly, it could be a link between simple steatosis and NASH.

Concluding remarks

The excessive hepatic lipid flux, which is derived from the disturbed metabolic balance of lipids, changes the absolute and relative levels of the various lipid species in the liver. Several lines of evidence highlight the critical role of non-TG lipids, such as SFAs, free cholesterol and ceramides, in the progression to NASH by triggering inflammation, cellular damage and fibrogenesis. At the subcellular level, the detrimental actions of toxic lipids cause the dysfunction of several cellular compartments as discussed in Sect. 3. Moreover, the interactions between these compartments aggravate lipotoxicity. Additionally, some “independent” factors, such as hypoxia, can further aggravate lipotoxic effects.

Therefore, counteracting lipotoxicity has emerged as a therapeutic strategy for NASH. As discussed in this review, TG is believed to be a non-toxic lipid. Promoting TG synthesis or lipid droplet biogenesis (e.g. by monounsaturated fatty acids) has been shown to counteract FFA-induced cellular toxicity, which is possibly due to the incorporation of toxic fatty acids into inert TGs [30]. Moreover, reducing oxidative stress (e.g. by vitamin E or metformin) also alleviates lipotoxicity [96, 116]. Furthermore, the use of chemical chaperones [e.g. tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA)] or stimulating the expression of ER chaperones like GRP78 (e.g. by hesperetin) to relieve ER stress also inhibit lipotoxicity [117, 118]. Candidate drugs that are currently in clinical trials are mainly aimed at reducing the lipid accumulation in the liver [3, 119]. However, investigating the consequences of changes in the composition of lipids in NAFLD might also be an important strategy to identify novel targets for intervention. In conclusion, future research on the relative contribution of lipotoxicity in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the elucidation of the effects of various lipid species are necessary and will provide directions for drug design as well as targeted therapies for NAFLD.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Arachidonic acid

- ATF6:

-

Activating transcription factor-6

- CHOP:

-

C/EBP homologous protein

- CIH:

-

Chronic intermittent hypoxia

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- CYPs:

-

Cytochromes P450

- DG:

-

Diacylglycerol

- DGATs:

-

Diacylglycerol acyltransferases

- DHA:

-

Docosahexaenoic acid

- DNL:

-

De novo lipogenesis

- DPA:

-

Docosapentaenoic acid

- EPA:

-

Eicosapentaenoic acid

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- FAO:

-

Fatty acid oxidation

- FAT/CD36:

-

Fatty acid translocase

- FATPs:

-

Fatty acid transport proteins

- FFAs:

-

Free fatty acids

- GPL:

-

Glycerophospholipid

- GRP78:

-

Glucose-regulated protein 78/immunoglobulin-heavy-chain-binding protein

- GSDMD:

-

Gasdermin D

- HIFs:

-

Hypoxia-inducible factors

- IR:

-

Insulin resistance

- IRE1α:

-

Inositol-requiring kinase 1α

- JNKs:

-

c-Jun N-terminal kinases

- LAL:

-

Lysosomal acid lipase

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- LPL:

-

Lipoprotein lipase

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharides

- LyPC:

-

Lysophosphatidylcholine

- MAFLD:

-

Metabolic associated fatty liver disease

- MLKL:

-

Mixed lineage kinase domain-like

- NAFL:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH:

-

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- NLRP3:

-

NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3

- OSAS:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- PC:

-

Phosphatidylcholine

- PE:

-

Phosphatidylethanolamine

- PERK:

-

Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase-like ER kinase

- PI:

-

Phosphatidylinositol

- PUMA:

-

p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis

- RIP:

-

Receptor-interacting protein

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SREBPs:

-

Sterol regulatory element binding proteins

- SERCA2:

-

Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2

- TGs:

-

Triglycerides

- TRAIL:

-

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- UPR:

-

Unfolded protein response

- VLDL:

-

Very-low-density-lipoprotein

- WAT:

-

White adipose tissue

References

Eslam M, et al. A new definition for metabolic associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73:201.

Byrne CD, Perseghin G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a risk factor for myocardial dysfunction? J Hepatol. 2018;68(4):640–2.

Friedman SL, et al. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2018;24(7):908–22.

Cholankeril G, et al. Liver transplantation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the US: temporal trends and outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(10):2915–22.

Younossi ZM, et al. Epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: implications for liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2019;103(1):22–7.

van den Berg EH, et al. Prevalence and determinants of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in lifelines: a large Dutch population cohort. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0171502.

Targher G, Lonardo A, Byrne CD. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic vascular complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(2):99–114.

Ekstedt M, et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology. 2015;61(5):1547–54.

Arab JP, Arrese M, Trauner M. Recent insights into the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2018;13:321–50.

Schoeler M, Caesar R. Dietary lipids, gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2019;20(4):461–72.

Lang S, Schnabl B. Microbiota and fatty liver disease-the known, the unknown, and the future. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28(2):233–44.

Bedossa P, et al. Systematic review of bariatric surgery liver biopsies clarifies the natural history of liver disease in patients with severe obesity. Gut. 2017;66(9):1688–96.

Fabbrini E, et al. Physiological mechanisms of weight gain-induced steatosis in people with obesity. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):79–81.

Cimini FA et al. Adipose tissue remodelling in obese subjects is a determinant of presence and severity of fatty liver disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020

Gentile CL, et al. The role of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue fatty acid composition in liver pathophysiology associated with NAFLD. Adipocyte. 2015;4(2):101–12.

Donnelly KL, et al. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Investig. 2005;115(5):1343–51.

Khan RS, et al. Modulation of insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2019;70(2):711–24.

Masoodi M, et al. Lipid signaling in adipose tissue: connecting inflammation and metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1851(4):503–18.

Zechner R, Madeo F, Kratky D. Cytosolic lipolysis and lipophagy: two sides of the same coin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(11):671–84.

Geisler CE, Renquist BJ. Hepatic lipid accumulation: cause and consequence of dysregulated glucoregulatory hormones. J Endocrinol. 2017;234(1):R1–21.

Miksztowicz V, et al. Hepatic lipase activity is increased in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease beyond insulin resistance. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(6):535–41.

Enooku K, et al. Hepatic FATP5 expression is associated with histological progression and loss of hepatic fat in NAFLD patients. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(2):227–43.

Han M, et al. Hepatocyte caveolin-1 modulates metabolic gene profiles and functions in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(2):104.

Li M, et al. Caveolin1 protects against diet induced hepatic lipid accumulation in mice. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0178748.

Wilson CG, et al. Hepatocyte-specific disruption of CD36 attenuates fatty liver and improves insulin sensitivity in HFD-Fed mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(2):570–85.

Andres-Blasco I, et al. Hepatic lipase deficiency produces glucose intolerance, inflammation and hepatic steatosis. J Endocrinol. 2015;227(3):179–91.

Teratani T, et al. Lipoprotein lipase up-regulation in hepatic stellate cells exacerbates liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatol Commun. 2019;3(8):1098–112.

Furuhashi M, Hotamisligil GS. Fatty acid-binding proteins: role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(6):489–503.

Jensen T, et al. Fructose and sugar: a major mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;68(5):1063–75.

Musso G, et al. Bioactive lipid species and metabolic pathways in progression and resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):282–302.

Afolabi PR, et al. The characterisation of hepatic mitochondrial function in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) using the (13)C-ketoisocaproate breath test. J Breath Res. 2018;12(4):046002.

Sunny NE, et al. Excessive hepatic mitochondrial TCA cycle and gluconeogenesis in humans with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Metab. 2011;14(6):804–10.

Petersen KF, et al. Assessment of hepatic mitochondrial oxidation and pyruvate cycling in NAFLD by (13)C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Cell Metab. 2016;24(1):167–71.

Mansouri A, Gattolliat CH, Asselah T. Mitochondrial dysfunction and signaling in chronic liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(3):629–47.

Moreno-Fernandez ME, et al. Peroxisomal beta-oxidation regulates whole body metabolism, inflammatory vigor, and pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. JCI Insight. 2018;3(6):e93626.

Weng H, et al. Pex11alpha deficiency impairs peroxisome elongation and division and contributes to nonalcoholic fatty liver in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304(2):E187–96.

Fabbrini E, et al. Alterations in adipose tissue and hepatic lipid kinetics in obese men and women with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(2):424–31.

Konishi K, et al. Advanced fibrosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis affects the significance of lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor. Atherosclerosis. 2020;299:32–7.

Perla FM, et al. The role of lipid and lipoprotein metabolism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Children (Basel). 2017;4(6):40.

Fon Tacer K, Rozman D. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: focus on lipoprotein and lipid deregulation. J Lipids. 2011;2011:783976.

Liangpunsakul S, Chalasani N. Lipid mediators of liver injury in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2019;316(1):G75–81.

Mota M, et al. Molecular mechanisms of lipotoxicity and glucotoxicity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2016;65(8):1049–61.

Puri P, et al. A lipidomic analysis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2007;46(4):1081–90.

Gorden DL, et al. Biomarkers of NAFLD progression: a lipidomics approach to an epidemic. J Lipid Res. 2015;56(3):722–36.

Chiappini F, et al. Metabolism dysregulation induces a specific lipid signature of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46658.

Peng KY, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction-related lipid changes occur in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease progression. J Lipid Res. 2018;59(10):1977–86.

Puri P, et al. The plasma lipidomic signature of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2009;50(6):1827–38.

Zhou Y, et al. Noninvasive detection of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis using clinical markers and circulating levels of lipids and metabolites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(10):1463–72.

Tiwari-Heckler S, et al. Circulating phospholipid patterns in NAFLD patients associated with a combination of metabolic risk factors. Nutrients. 2018;10(5):649.

Lebeaupin C, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling and the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):927–47.

Arruda AP, Hotamisligil GS. Calcium homeostasis and organelle function in the pathogenesis of obesity and diabetes. Cell Metab. 2015;22(3):381–97.

Gonzalez-Rodriguez A, et al. Impaired autophagic flux is associated with increased endoplasmic reticulum stress during the development of NAFLD. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1179.

Lopez-Domenech S, et al. Moderate weight loss attenuates chronic endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in human obesity. Mol Metab. 2019;19:24–33.

Chen X, et al. Oleic acid protects saturated fatty acid mediated lipotoxicity in hepatocytes and rat of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Life Sci. 2018;203:291–304.

Kakisaka K, et al. Mechanisms of lysophosphatidylcholine-induced hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302(1):G77-84.

Akazawa Y, Nakao K. Lipotoxicity pathways intersect in hepatocytes: Endoplasmic reticulum stress, c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1, and death receptors. Hepatol Res. 2016;46(10):977–84.

Cunha DA, et al. Death protein 5 and p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis mediate the endoplasmic reticulum stress-mitochondrial dialog triggering lipotoxic rodent and human beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetes. 2012;61(11):2763–75.

Chan JY, et al. The balance between adaptive and apoptotic unfolded protein responses regulates beta-cell death under ER stress conditions through XBP1, CHOP and JNK. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;413:189–201.

Ali ES, Petrovsky N. Calcium signaling as a therapeutic target for liver steatosis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2019;30(4):270–81.

Piperi C, Adamopoulos C, Papavassiliou AG. XBP1: a pivotal transcriptional regulator of glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27(3):119–22.

Jo H, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces hepatic steatosis via increased expression of the hepatic very low-density lipoprotein receptor. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1366–77.

Chen X, et al. Hepatic ATF6 increases fatty acid oxidation to attenuate hepatic steatosis in mice through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Diabetes. 2016;65(7):1904–15.

Bailly-Maitre B, et al. Hepatic Bax inhibitor-1 inhibits IRE1alpha and protects from obesity-associated insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(9):6198–207.

Achard CS, Laybutt DR. Lipid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in liver cells results in two distinct outcomes: adaptation with enhanced insulin signaling or insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 2012;153(5):2164–77.

Pirola CJ, et al. Epigenetic modification of liver mitochondrial DNA is associated with histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2013;62(9):1356–63.

Einer C, et al. Mitochondrial adaptation in steatotic mice. Mitochondrion. 2018;40:1–12.

Egnatchik RA, et al. Palmitate-induced activation of mitochondrial metabolism promotes oxidative stress and apoptosis in H4IIEC3 rat hepatocytes. Metabolism. 2014;63(2):283–95.

Gao Y, et al. Mitochondrial DNA from hepatocytes induces upregulation of interleukin-33 expression of macrophages in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(6):637–43.

Win S, et al. New insights into the role and mechanism of c-Jun-N-terminal kinase signaling in the pathobiology of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(5):2013–24.

Li Z, et al. The lysosomal–mitochondrial axis in free fatty acid-induced hepatic lipotoxicity. Hepatology. 2008;47(5):1495–503.

Feldstein AE, et al. Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatology. 2004;40(1):185–94.

Tovoli F, et al. A relative deficiency of lysosomal acid lypase activity characterizes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(6):1134.

Baratta F, et al. Reduced lysosomal acid lipase activity in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(7):750–4.

Selvakumar PK, et al. Reduced lysosomal acid lipase activity—a potential role in the pathogenesis of non alcoholic fatty liver disease in pediatric patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48(8):909–13.

Himes RW, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency unmasked in two children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4):e20160214.

Wang X, et al. Defective lysosomal clearance of autophagosomes and its clinical implications in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. FASEB J. 2018;32(1):37–51.

Schweitzer SC, et al. Endogenous versus exogenous fatty acid availability affects lysosomal acidity and MHC class II expression. J Lipid Res. 2006;47(11):2525–37.

Hirsova P, et al. Lipotoxic lethal and sublethal stress signaling in hepatocytes: relevance to NASH pathogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(10):1758–70.

Zhang T, et al. SIRT3 promotes lipophagy and chaperon-mediated autophagy to protect hepatocytes against lipotoxicity. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27(1):329–44.

Miyagawa K, et al. Lipid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress impairs selective autophagy at the step of autophagosome–lysosome fusion in hepatocytes. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(7):1861–73.

Allaire M, et al. Autophagy in liver diseases: time for translation? J Hepatol. 2019;70(5):985–98.

Singh R, et al. Differential effects of JNK1 and JNK2 inhibition on murine steatohepatitis and insulin resistance. Hepatology. 2009;49(1):87–96.

Pal M, Febbraio MA, Lancaster GI. The roles of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNKs) in obesity and insulin resistance. J Physiol. 2016;594(2):267–79.

Machado MV, et al. Caspase-2 promotes obesity, the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2096.

Machado MV, et al. Reduced lipoapoptosis, hedgehog pathway activation and fibrosis in caspase-2 deficient mice with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut. 2015;64(7):1148–57.

Wilson CH, Kumar S. Caspases in metabolic disease and their therapeutic potential. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(6):1010–24.

Kakisaka K, et al. A hedgehog survival pathway in “undead” lipotoxic hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 2012;57(4):844–51.

Hirsova P, Gores GJ. Death receptor-mediated cell death and proinflammatory signaling in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;1(1):17–27.

Idrissova L, et al. TRAIL receptor deletion in mice suppresses the inflammation of nutrient excess. J Hepatol. 2015;62(5):1156–63.

Schwabe RF, Luedde T. Apoptosis and necroptosis in the liver: a matter of life and death. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(12):738–52.

Dara L, Liu ZX, Kaplowitz N. Questions and controversies: the role of necroptosis in liver disease. Cell Death Discov. 2016;2:16089.

Dara L, Kaplowitz N. The many faces of RIPK3: what about NASH? Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1411–3.

Luedde M, et al. RIP3, a kinase promoting necroptotic cell death, mediates adverse remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103(2):206–16.

Afonso MB, et al. Necroptosis is a key pathogenic event in human and experimental murine models of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Sci (Lond). 2015;129(8):721–39.

Majdi A, et al. Inhibition of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 improves experimental non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2020;72(4):627–35.

Geng Y, et al. Protective effect of metformin against palmitate-induced hepatic cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(3):165621.

Roychowdhury S, et al. Receptor interacting protein 3 protects mice from high-fat diet-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1518–33.

Beier JI, Banales JM. Pyroptosis: an inflammatory link between NAFLD and NASH with potential therapeutic implications. J Hepatol. 2018;68(4):643–5.

Gautheron J, Gores GJ, Rodrigues CMP. Lytic cell death in metabolic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2020;73:394.

Csak T, et al. Fatty acid and endotoxin activate inflammasomes in mouse hepatocytes that release danger signals to stimulate immune cells. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):133–44.

Zhang NP, et al. Impaired mitophagy triggers NLRP3 inflammasome activation during the progression from nonalcoholic fatty liver to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Lab Investig. 2019;99(6):749–63.

Cabrera D, et al. Andrographolide ameliorates inflammation and fibrogenesis and attenuates inflammasome activation in experimental non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3491.

Hernandez A, et al. Extracellular vesicles in NAFLD/ALD: from pathobiology to therapy. Cells. 2020;9(4):817.

Hirsova P, et al. Lipid-induced signaling causes release of inflammatory extracellular vesicles from hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):956–67.

Lee YS, et al. Exosomes derived from palmitic acid-treated hepatocytes induce fibrotic activation of hepatic stellate cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3710.

Kakazu E, et al. Hepatocytes release ceramide-enriched pro-inflammatory extracellular vesicles in an IRE1alpha-dependent manner. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(2):233–45.

Ibrahim SH, et al. Mixed lineage kinase 3 mediates release of C–X–C motif ligand 10-bearing chemotactic extracellular vesicles from lipotoxic hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2016;63(3):731–44.

Sundaram SS, et al. Nocturnal hypoxia-induced oxidative stress promotes progression of pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;65(3):560–9.

Mesarwi OA, Loomba R, Malhotra A. Obstructive sleep apnea, hypoxia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(7):830–41.

Viglino D, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(6):160.

Hernandez A, et al. Chemical hypoxia induces pro-inflammatory signals in fat-laden hepatocytes and contributes to cellular crosstalk with Kupffer cells through extracellular vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866:165753.

Hernandez A, et al. Chemical hypoxia induces pro-inflammatory signals in fat-laden hepatocytes and contributes to cellular crosstalk with Kupffer cells through extracellular vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(6):165753.

Berthiaume F, et al. Steatosis reversibly increases hepatocyte sensitivity to hypoxia-reoxygenation injury. J Surg Res. 2009;152(1):54–60.

Morello E, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha drives nonalcoholic fatty liver progression by triggering hepatocyte release of histidine-rich glycoprotein. Hepatology. 2018;67(6):2196–214.

Arai T, Tanaka M, Goda N. HIF-1-dependent lipin1 induction prevents excessive lipid accumulation in choline-deficient diet-induced fatty liver. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14230.

Vadarlis A et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the effect of vitamin E supplementation in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020

Geng Y, et al. Hesperetin protects against palmitate-induced cellular toxicity via induction of GRP78 in hepatocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2020;404:115183.

Han J, Kaufman RJ. The role of ER stress in lipid metabolism and lipotoxicity. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(8):1329–38.

Esler WP, Bence KK. Metabolic targets in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;8(2):247–67.

Funding

This project is financially supported by the China Scholarship Council (File no. 201506210062) (Y.G.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, HM, KNF, HB and VEM; writing—original draft preparation, YG, HB; writing—review and editing, YG, HM, HB, and VEM; supervision, HM and HB.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no potential conflict of interest.

Animal research (ethics)

This article does not contain any direct studies with animal subjects.

Consent to participate and publish (ethics)

None declared. All the authors have seen and approved the submission of this version of the manuscript and take full responsibility for the manuscript.

Clinical trials registration

This article does not contain any direct studies with human subjects.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geng, Y., Faber, K.N., de Meijer, V.E. et al. How does hepatic lipid accumulation lead to lipotoxicity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease?. Hepatol Int 15, 21–35 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-020-10121-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-020-10121-2