Abstract

Background

There is no uniform definition for cerebral microdialysis (CMD) probe location with respect to focal brain lesions, and the impact of CMD-probe location on measured molecule concentrations is unclear.

Methods

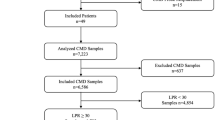

We retrospectively analyzed data of 51 consecutive subarachnoid hemorrhage patients with CMD-monitoring between 2010 and 2016 included in a prospective observational cohort study. Microdialysis probe location was assessed on all brain computed tomography (CT) scans performed during CMD-monitoring and defined as perilesional in the presence of a focal hypodense or hyperdense lesion within a 1-cm radius of the gold tip of the CMD-probe, or otherwise as normal-appearing brain tissue.

Results

Probe location was detected in normal-appearing brain tissue on 53/143 (37%) and in perilesional location on 90/143 (63%) CT scans. In the perilesional area, CMD-glucose levels were lower (p = 0.003), whereas CMD-lactate (p = 0.002), CMD-lactate-to-pyruvate-ratio (LPR; p < 0.001), CMD-glutamate (p = 0.002), and CMD-glycerol levels (p < 0.001) were higher. Neuroglucopenia (CMD-glucose < 0.7 mmol/l, p = 0.002), metabolic distress (p = 0.002), and mitochondrial dysfunction (p = 0.005) were more common in perilesional compared to normal-appearing brain tissue. Development of new lesions in the proximity of the CMD-probe (n = 13) was associated with a decrease in CMD-glucose levels, evidence of neuroglucopenia, metabolic distress, as well as increasing CMD-glutamate and CMD-glycerol levels. Neuroglucopenia was associated with poor outcome independent of probe location, whereas elevated CMD-lactate, CMD-LPR, CMD-glutamate, and CMD-glycerol levels were only predictive of poor outcome in normal-appearing brain tissue.

Conclusions

Focal brain lesions significantly impact on concentrations of brain metabolites assessed by CMD. With the exception of CMD-glucose, the prognostic value of CMD-derived parameters seems to be higher when assessed in normal-appearing brain tissue. CMD was sensitive to detect the development of new focal lesions in vicinity to the neuromonitoring probe. Probe location should be described in the research reporting brain metabolic changes measured by CMD and integrated in statistical models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerebral microdialysis (CMD) is a powerful monitoring tool providing insight into cerebral metabolic changes in patients suffering from acute brain injury [1]. In poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) patients, research has focused on the detection of delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) and the prediction of functional outcome [2]. Recent studies also demonstrated its utility in elucidating mechanisms of early brain injury [3], monitoring the effects of interventions on cerebral metabolism, and guiding systemic glucose management [2, 4, 5].

Current guidelines recommend CMD-catheter placement in the frontal watershed of the hemisphere ipsilateral to the aneurysm or in the vascular territory deemed at the greatest risk of developing secondary brain injury [1]. Catheter location should be reported in all research manuscripts reporting CMD-data, as CMD is a local monitoring method and concentrations of brain metabolites depend on focal brain pathology surrounding the probe. So far, no uniform recommendation of how to classify catheter location exists, resulting in a large heterogeneity of definitions in the literature [2]. Marked differences in CMD-derived metabolites in normal-appearing and (peri-)lesional brain tissue have been reported in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients [6,7,8,9]. Accordingly, changes detected in the perilesional area may need to be interpreted differently than in normal-appearing brain tissue and even imply separate specific treatment consequences. Furthermore, it is unclear how CMD-derived biomarkers are associated with outcome depending on probe location [10].

Focal brain lesions after SAH include hyperdense and hypodense areas on brain computed tomography (CT), reflecting parenchymal hemorrhage, focal edema, and ischemia. Acute focal neurological deficits were associated with differences in cerebral metabolism, but the authors did not report spatial relation of CMD-probes to focal brain lesions [11]. The importance of CMD-probe location in the detection of silent cerebral infarcts has also been reported [12]. Changes in brain metabolism were detected hours preceding the detection of the infarct by head CT scans when probes were in the vicinity of the ischemic tissue; to the contrary, CMD was unable to detect ischemia when probe location was remote from the lesion (contralateral hemisphere or > 4 cm) [12].

In this study, we aimed to investigate the impact of catheter location on brain interstitial metabolite concentrations using a systematic approach and to study temporal dynamics in patients developing focal pathologies during monitoring time. We hypothesized that patterns of ischemia and metabolic derangement would be more common in the vicinity of focal brain lesions and that the association between cerebral metabolism and functional outcome of patients would depend on catheter location.

Methods

Patient Selection

This is a retrospective analysis of prospectively recorded observational data of 51/64 consecutive SAH-patients fulfilling the inclusion/exclusion criteria admitted to the neurological intensive care unit at the Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria, requiring multimodal neuromonitoring between 2010 and 2016. According to our institutional policy, invasive neuromonitoring is only performed in mechanically ventilated patients (poor admission grade or secondary deterioration). The study was approved by the local ethics committee, has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients according to federal regulations. Inclusion criteria were (1) admission with non-traumatic SAH, (2) ≥ 18 years of age, (3) neuromonitoring including CMD and (4) at least one brain CT scan during the time of CMD-monitoring. We excluded patients in whom a CMD-catheter was inserted but was dysfunctional (i.e. did not yield samples n = 7), patients lacking head CT scans during CMD-monitoring measurements would rather represent concentrations in blood, not in brain tissue, n = 3), leaving 51 patients eligible for analysis.

Grading and Patient Care

Disease severity was graded using the Hunt and Hess scale and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score [13, 14]. Head CTs were performed on admission, after aneurysm treatment and when clinically needed and graded by an independent neuroradiologist (PR) using the modified Fisher score, SAH-sum score, and intraventricular hemorrhage sum score and were assessed for the presence of global cerebral edema (GCE) [15,16,17]. Clinical care was based on current international guidelines [18, 19], with the exception of continuous intravenous application of nimodipine. Ruptured aneurysms were treated by surgical clipping or endovascular coiling. Intravenous fluids (crystalloids and colloids), vasopressors (noradrenalin and phenylephrine), and dobutamine were used for hemodynamic stabilization. All patients were comatose during the period of invasive neuromonitoring and routinely received continuous intravenous midazolam and sufentanil. Patients were followed with transcranial color-coded duplex sonography. DCI was defined as new infarct on CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), not attributable to other causes [20]. Functional outcome was assessed 3 months after SAH using the modified Rankin scale (mRS). In view of the high proportion of poor functional outcome in poor-grade SAH-patients, a mRS-score of ≤ 3 was defined as good functional outcome.

Data Collection and Neuromonitoring

Patient characteristics, interventions, complications, and outcome were prospectively recorded in our institutional SAH-database. Continuous parameters were recorded in our patient data management system (Centricity™ Critical Care 8.1 SP7; GE Healthcare Information Technologies, Dornstadt, Germany) and meaned over the CMD-sampling time (1 h). Based on clinical and imaging criteria, patients received multimodal neuromonitoring including CMD. The CMD-probe (71 High Cut-Off Brain Microdialysis Catheter, membrane length 1 cm, pore size 100 kDa) was tunneled and placed in the white matter of the frontal watershed ipsilateral to the aneurysm or the vascular territory exhibiting the maximal pathology. Not more than 1 CMD-catheter was inserted per patient. Isotonic perfusion fluid [Perfusion Fluid CNS (central nervous system), Mdialysis™] was used at a flow rate of 0.3 μl/min. CMD samples were immediately analyzed with CMA 600 or Iscusflex (all CMD-equipment by M Dialysis AB, Stockholm, Sweden) for CMD-glucose, CMD-pyruvate, CMD-lactate, CMD-glutamate, and CMD-glycerol concentrations. The first sample was drawn at least 1 h after probe insertion and discarded to avoid artefacts. Metabolic distress was defined as a lactate-to-pyruvate ratio (LPR) > 40, mitochondrial dysfunction as LPR > 30 together with CMD-pyruvate > 70 µmol/l, and neuroglucopenia as CMD-glucose < 0.7 mmol/l.

Probe Location

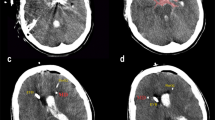

Probe location was assessed on all available head CT scans during CMD-monitoring by an independent neuroradiologist, blinded to clinical and neuromonitoring data, with respect to focal brain lesions (Fig. 1). Perilesional probe location was defined as the presence of a focal hyperdense (SAH-related parenchymal hemorrhage, thick SAH-clot) and/or focal hypodense (perioperative edema, perihematomal edema, other focal brain edema, initial ischemic stroke, periinterventional infarction, delayed cerebral edema) CT-lesion within 1 cm of the edge of the gold tip of the CMD-probe. Direct contact of the tip with a hypodense lesion was additionally subclassified as intralesional probe location, while CMD-data with probe location inside a hyperdense lesion were excluded from the analysis. If there was no focal lesion within 1 cm of the tip, probe location was graded as normal-appearing brain tissue. CMD-values of the 24 h preceding the CT scan were analyzed. For the assessment of temporal dynamics, we classified the CT scans into three groups (days 0–3, days 4–7 and after 7 days).

Examples for probe location in normal-appearing brain tissue (a), perilesional (b), and intralesional (c) probe location on axial computed tomography scans of the brain; panel d is a schematic diagram describing probe location classification. The white circle represents a parenchymal hemorrhage with perifocal edema (dark gray area), surrounded by normal-appearing brain tissue (light gray area). Tips of microdialysis probes completely surrounded (location 1) or in direct contact with (location 2) a hypodense area were classified as intralesional. Perilesional location was defined as lesion within 1 cm of the catheter tip (location 3). Location 4 represents normal-appearing brain tissue. The metabolic profile of locations 1, 2 and 3 were not different and summarized for comparison with location 4

Statistics

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard error of mean or median and interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Categorical variables are reported as count and proportions in each group. Time-series data were analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with an autoregressive process of the first order to account for repeated measurements within subjects. The impact of probe location on cerebral metabolism was assessed in a linear GEE-model with the respective CMD parameter as dependent variable and dichotomized probe location as independent variable. In the same manner, the associations with functional outcome were analyzed by using the dichotomized outcome variable as independent variable. Statistical models were adjusted for important covariates as specified in the results. All analyses were performed with IBM-SPSS V24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p value < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics, hospital complications, and outcome of 51 SAH-patients are given in Table 1. Neuromonitoring was started on day 1 [1, 2] after SAH. CMD was performed for a median of 9 (IQR 6-13) days. In total, 143 head CT scans with a median of two scans [1,2,3] per patient were graded. Overall, 2259 CMD samples [median 39 (IQR 23-65) per patient] were analyzed.

CMD-probes were detected in normal-appearing brain tissue on 53/143 scans (37%) and in perilesional location on 90/143 scans (63%). There was no difference in metabolite concentrations between intralesional and perilesional probe location, except for a higher LPR (p = 0.04) in intralesional hypodense probe location in close vicinity (within 1 cm of the tip) to a hyperdense lesion.

Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) did not differ between measurements in normal-appearing and perilesional brain tissue (p = 0.484, supplemental Figure). Mean values of CMD parameters in normal-appearing and perilesional brain tissue are shown in Table 2. CMD-glucose levels were lower in perilesional probe location (p = 0.003), whereas CMD-lactate (p < 0.002), CMD-LPR (p < 0.001), CMD-glutamate (p = 0.002), and CMD-glycerol levels (p < 0.001) were higher. Temporal dynamics of cerebral metabolism are shown in Fig. 2. Neuroglucopenia (27.1 vs. 8.8%, p = 0.002), metabolic distress (33.1 vs. 8.6%, p = 0.002), and mitochondrial dysfunction (50.3 vs. 21.4%, p = 0.005) were more common in perilesional compared to normal-appearing brain tissue. All analyses were adjusted for CPP.

Violin plots depicting concentrations and temporal dynamics of CMD-glucose (a), CMD-lactate (b), CMD-pyruvate (c), CMD-LPR (d), CMD-glutamate (e), and CMD-glycerol (f) in normal-appearing brain tissue (light gray) and perilesional brain tissue (dark gray); the x-axis indicates time from SAH in three groups [days 0–3 (24 CT scans and 273 samples in normal-appearing tissue, 37 CT scans and 481 samples in perilesional tissue), days 4–7 (20 CT scans and 363 samples in normal-appearing tissue, 23 CT scans and 418 samples in perilesional tissue), and after day 7 (9 CT scans and 189 samples in normal-appearing tissue, 30 CT scans and 535 samples in perilesional tissue)]; the outer line of the plots shows the distribution of all data points. Boxes indicate median and IQR. The dashed line within the boxes represents the mean. p values above the plots describe the significance of differences between normal-appearing and perilesional brain tissue during the group of days specified below. Dashed lines connecting plots indicate significant changes over time (p values shown next to lines); statistical analyses were performed using a linear model in GEEs with the respective CMD parameters as dependent variable. Models were adjusted for age, gender, Hunt and Hess grade, and cerebral perfusion pressure. All p-values < 0.1 are reported. CMD cerebral microdialysis, LPR lactate-to-pyruvate ratio, IQR interquartile range

Changing Brain Pathology in Relation to Probe Location

In 13 patients, we found a transition of CMD-probe location from normal-appearing to perilesional brain tissue by either the expansion of an existing focal pathology, the occurrence of a new focal lesion, or the dislocation of the catheter tip. CMD-glucose levels significantly decreased (1.58 ± 0.06 to 1.24 ± 0.06 mmol/l, p = 0.039), whereas CMD-glutamate (8.39 ± 1.18 to 24.33 ± 2.43 µmol/l, p = 0.006) and CMD-glycerol levels (39.98 ± 3.28 to 60.26 ± 3.59 µmol/l, p = 0.004) increased with the change in probe location. CMD-lactate levels non-significantly increased (3.44 ± 0.06 to 3.95 ± 0.19, p = 0.60), and CMD-pyruvate levels non-significantly decreased (137.9 ± 4.26 to 117.6 ± 3.29 µmol/l, p = 0.16), resulting in a trend toward higher LPR (28.28 ± 0.56 to 34.01 ± 1.31, p = 0.08). The frequency of metabolic distress increased from 6.2 to 21.3% (p = 0.046), and the frequency of neuroglucopenia increased from 7.2 to 30.0% (p = 0.01). All statistical models were adjusted for age, gender, Hunt and Hess grade, and CPP.

CMD-Probe Location and Outcome

Patients with poor outcome after 3 months had lower CMD-glucose levels (1.54 ± 0.03 vs. 1.77 ± 0.04, p = 0.014) and higher levels of CMD-lactate (4.60 ± 0.06 vs. 3.08 ± 0.09, p = 0.001), CMD-LPR (37.5 ± 0.57 vs. 27.9 ± 0.65, p = 0.012), CMD-glutamate (33.7 ± 1.6 vs. 19.3 ± 1.7, p = 0.006), and CMD-glycerol (96.8 ± 5.3 vs. 48.5 ± 2.4, p = 0.004). There were no differences in CMD-pyruvate levels. Detailed information on temporal dynamics of CMD parameters with respect to probe location and functional outcome is provided in Fig. 3.

Median (IQR) and temporal dynamics of CMD-glucose (a), CMD-lactate (b), CMD-pyruvate (c), CMD-LPR (d), CMD-glycerol (e), and CMD-glutamate (f) in patients with good (black bars) and poor functional outcome (dark gray bars); plus signs within plots represent the mean; data are separately shown for normal-appearing brain tissue (1) and perilesional brain tissue (2). The x-axis indicates time from SAH in three groups: days 0–3 [184 samples of patients with good outcome (53 perilesional, 131 normal-appearing tissue) and 570 samples of patients with poor outcome (428 perilesional, 142 normal-appearing tissue)]; days 4–7 [246 samples of patients with good outcome (85 perilesional, 161 normal-appearing tissue) and 535 samples of patients with poor outcome (333 perilesional, 202 normal-appearing tissue)]; and after day 7 [149 samples of patients with good outcome (56 perilesional, 93 normal-appearing tissue) and 575 samples of patients with poor outcome (479 perilesional, 96 normal-appearing tissue)]; p values above the plots describe the significance of differences between patients with good and poor outcome during the group of days specified below. Dashed lines connecting plots indicate significant changes over time (p values shown next to lines); statistical analyses were performed using a linear model in GEEs with the respective CMD parameters as dependent variable. Models were adjusted for age, gender, Hunt and Hess grade, and cerebral perfusion pressure. All p values < 0.1 are reported. CMD cerebral microdialysis, LPR lactate-to-pyruvate ratio, IQR interquartile range

CMD-glucose levels were lower in patients with poor functional outcome in perilesional (p = 0.041), but not in normal-appearing brain tissue (p = 0.63). In perilesional brain tissue, these differences were more pronounced during the first week after SAH (p = 0.002). Interestingly, neuroglucopenia was significantly associated with poor functional outcome in either of the probe locations (p = 0.015 and p = 0.016).

CMD-lactate levels and CMD-LPR were higher in patients with poor functional outcome in normal-appearing (p = 0.014 and p < 0.001), but not in perilesional brain tissue (p = 0.35 and p = 0.56). Metabolic distress and mitochondrial dysfunction were strongly associated with poor outcome in normal-appearing (p = 0.001 and p = 0.002), but not in perilesional brain tissue (p = 0.51 and p = 0.69).

CMD-glutamate levels were higher in patients with poor functional outcome in normal-appearing (p < 0.001), but not in perilesional brain tissue (p = 0.57). CMD-glycerol levels were higher in patients with poor functional outcome in normal-appearing (p < 0.001), but not in perilesional brain tissue (p = 0.23).

All analyses were adjusted for age, gender, Hunt and Hess grade, and CPP.

CMD and DCI

DCI was associated with lower CMD-glucose levels (p = 0.002) and neuroglucopenia (p = 0.004) in normal-appearing brain tissue, as well as a higher LPR (p = 0.001) and metabolic distress (p = 0.008) in perilesional brain tissue.

Discussion

Our main findings are that the brain metabolic profile assessed by CMD largely depends on probe location, that lesion development can be detected by trend analysis of brain metabolites, and that probe location should be taken into account when CMD-derived parameters are used for neuroprognostication.

CMD is a local monitoring tool quantifying small metabolites in brain tissue surrounding the CMD-membrane (cylinder with a length of 1 cm) [21]. As shown in TBI-patients, perilesional tissue exhibited lower levels of CMD-glucose and higher levels of CMD-lactate, CMD-LPR, CMD-glutamate, and CMD-glycerol compared to normal-appearing brain tissue [6,7,8]. Therefore, probe location should be an integral part when interpreting brain metabolic changes assessed by CMD. So far, probe positioning has been neglected in most reports due to the lack of a precise definition based on conventional imaging techniques [2]. Here, we propose a simple method using clinical routine head CT scans and describe metabolic profiles in perilesional and normal-appearing brain tissue.

CMD-glucose levels were lower in perilesional location when compared to normal-appearing brain tissue. Absolute brain interstitial glucose levels are difficult to interpret as they depend on complex interactions including systemic glucose delivery, glucose transport across the blood–brain barrier and diffusion in brain tissue as well as cerebral energy consumption. We previously investigated the effect of enteral nutrition on brain glucose levels in SAH-patients and detected a significant increase independent of probe location [2]. However, absolute concentrations of CMD-glucose were significantly lower in perilesional brain tissue [2]. In the current study, we found a higher incidence of neuroglucopenia in the proximity of focal lesions. This may be explained by a decreased cerebral blood flow in hypodense areas (on head CT scans) [22], or glucose hypermetabolism, as previously reported in SAH-patients with GCE and in the perihematomal area of intracerebral hemorrhage patients [23, 24]. In the current study, we found neuroglucopenia to be associated with poor outcome irrespective of probe location; however, we found that absolute CMD-glucose levels measured in normal-appearing brain tissue may not accurately predict outcome. Based on the expert recommendation to treat pathologically low CMD-glucose levels, our findings are important for future prospective interventional trials [1]. However, the effect of a liberal glucose regimen may result in minor increases when CMD-glucose is measured in the perilesional area [2]. Moreover, trend analysis revealing decreasing CMD-glucose levels may indicate the development of new focal brain lesions as previously described [12].

Not only cumulative mean CMD-lactate and CMD-LPR levels, but also their temporal dynamics significantly differed between probe locations. The initial peak and consecutive decrease in CMD-lactate levels and CMD-LPR in perilesional tissue is reminiscent of the pattern found in SAH-patients with acute focal neurological deficits on admission [25]. Elevated CMD-lactate levels have traditionally been associated with anaerobic metabolism and poor outcome [2]. While our results confirm an association of overall higher CMD-lactate levels with poor outcome, integration of probe location confirmed this independent association primarily in normal-appearing brain tissue. Similar to CMD-lactate levels, elevated CMD-LPR is indicative for either cerebral ischemia or even more frequent, mitochondrial dysfunction [2, 26]. In our patients, metabolic distress and mitochondrial dysfunction were more common in perilesional brain tissue. As higher CMD-lactate levels and CMD-LPR were associated with poor outcome in normal-appearing brain tissue, an impaired oxidative brain metabolism seems to indicate adverse pathophysiologic processes beyond ischemia or focal lesions visible on head CT contributing to poor functional outcome. Recently, the metabolic profile of mitochondrial dysfunction was defined as elevated LPR together with normal-to-elevated pyruvate concentrations [26]. The impact of mitochondrial dysfunction on functional outcome is still unclear. We found it to be more common in the vicinity of focal lesions, but it was only associated with poor outcome in normal-appearing brain tissue. The incidence of highly elevated CMD-LPR, referred to as metabolic distress, however, significantly increased when new lesions developed, which is in line with the previous studies [12]. This may indicate that the frequency of the occurrence of metabolic distress is a more sensitive marker of emerging brain pathology than absolute LPR values, which did not significantly increase before new lesions were detected on CT scans. Elevated CMD-lactate levels do not only result from ischemia, but also from hyperglycolysis, which was described in SAH-patients with GCE [23]. In contrast to hypoxic/ischemic lactate, hyperglycolytic elevated lactate has even been associated with good functional outcome [27], possibly explaining the missing association between CMD-lactate levels and CMD-LPR in perilesional brain tissue. In summary, the reason for the lack of an association between metabolic derangement/mitochondrial dysfunction with functional outcome in perilesional brain tissue remains speculative. Metabolic distress in the perilesional area may simply represent the pathology associated with focal brain lesions and not (or less) reflect the metabolic condition of the whole brain. In contrary, if metabolic distress and/or mitochondrial dysfunction is detected in radiologically normal-appearing brain tissue, this may reflect global pathologies including generalized edema and generalized relative hypoperfusion [3], high-grade neuroinflammation [28], and axonal damage [29], which may better prognosticate functional outcome.

In the current consensus statement, the measurements of CMD-glutamate and CMD-glycerol were regarded as having questionable relevance for clinical patient management [1]. CMD-glutamate is a marker of excitotoxicity, with excess levels being associated with (and potentially contributing to) ischemia and poor outcome. CMD-glycerol is a marker of cellular decay. Here, we describe an association of elevated CMD-glutamate and CMD-glycerol levels with poor outcome in normal-appearing, but not in perilesional brain tissue. Similar to our observations regarding CMD-lactate and CMD-LPR, this indicates that monitoring brain metabolism may capture tissue damage not depicted by CT-imaging. Furthermore, there was a much larger elevation in CMD-glutamate and CMD-glycerol levels in the proximity of focal brain lesions. In line with this, higher CMD-glutamate and CMD-glycerol concentrations were previously described in patients with focal neurological deficits; however, the authors did not report a spatial relation of brain lesions and the CMD-probe [11, 25]. Our observation of a pronounced increase in CMD-glutamate and CMD-glycerol associated with the development of new focal lesions in the vicinity of the CMD-probe may strengthen the indication for measuring these parameters bedside, especially as we found only a non-significant trend toward higher CMD-LPR levels.

We are aware of limitations using CT scans for grading probe location, which are not sensitive enough to detect minor ischemic or hemorrhagic pathologies which would potentially be visible using MRI. Unsurprisingly, we found a slightly different metabolic profile with lower CMD-pyruvate levels and a higher CMD-LPR in normal-appearing brain tissue compared to the previously reported profile in healthy brain tissue of uninjured patients [30]. Further limitations include patient population, which was a highly selected cohort of poor-grade SAH-patients undergoing invasive neuromonitoring. Still, our data reflect clinical practice of CMD in poor-grade ventilated patients. The volume of tissue sampled by a CMD-catheter is a cylinder with a height of 10 mm and a diameter of a few millimeters [21]. With respect to these technical suppositions and guided by the previous studies, we used a distance of 1 cm from the CMD-probe to distinguish normal-appearing from perilesional tissue. Furthermore, we did not use all available CMD-data, but only the 24-h preceding CT scans, which may influence outcome analyses. For this reason, we also chose not to further investigate the associations between CMD parameters and DCI in different probe locations.

Our findings support the use of CMD as tool to detect brain metabolic changes associated with secondary brain injury. Further research is needed to identify potential treatment targets derived from metabolic monitoring. Treating neuroglucopenia appears to be a suitable approach, as it was associated with poor functional outcome irrespective of probe location and the development of new focal brain lesions. Our data indicate that CMD-probe placement in normal-appearing brain tissue may yield more relevant information than placement in perilesional tissue. The integration of brain metabolic parameters may further increase the sensitivity of neuroprognostication after acute brain injury.

Conclusions

Focal brain lesions significantly impact on absolute concentrations and temporal dynamics of CMD parameters. The prognostic value of most CMD-derived metabolites seems to be limited to measurement in normal-appearing brain tissue. In contrast, neuroglucopenia remains a strong prognostic indicator independent of probe location. CMD was sensitive to detect the development of new focal lesions in vicinity to the probe. Based on our findings, probe location should be described in research reporting brain metabolic changes measured by CMD and integrated in statistical models.

References

Hutchinson PJ, Jalloh I, Helmy A, et al. Consensus statement from the 2014 international microdialysis forum. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1517–28.

Helbok R, Kofler M, Schiefecker AJ, et al. Clinical use of cerebral microdialysis in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage-state of the art. Front Neurol. 2017;8:565.

Helbok R, Schiefecker AJ, Beer R, et al. Early brain injury after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a multimodal neuromonitoring study. Crit Care. 2015;19:75.

Helbok R, Kurtz P, Schmidt JM, et al. Effect of mannitol on brain metabolism and tissue oxygenation in severe haemorrhagic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:378–83.

Kofler M, Schiefecker AJ, Beer R, et al. Enteral nutrition increases interstitial brain glucose levels in poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:518–27.

Engstrom M, Polito A, Reinstrup P, et al. Intracerebral microdialysis in severe brain trauma: the importance of catheter location. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:460–9.

Nordstrom CH, Reinstrup P, Xu W, Gardenfors A, Ungerstedt U. Assessment of the lower limit for cerebral perfusion pressure in severe head injuries by bedside monitoring of regional energy metabolism. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:809–14.

Timofeev I, Czosnyka M, Carpenter KL, et al. Interaction between brain chemistry and physiology after traumatic brain injury: impact of autoregulation and microdialysis catheter location. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:849–60.

Vespa PM, O’Phelan K, McArthur D, et al. Pericontusional brain tissue exhibits persistent elevation of lactate/pyruvate ratio independent of cerebral perfusion pressure. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1153–60.

Timofeev I, Carpenter KL, Nortje J, et al. Cerebral extracellular chemistry and outcome following traumatic brain injury: a microdialysis study of 223 patients. Brain J Neurol. 2011;134:484–94.

Sarrafzadeh A, Haux D, Sakowitz O, et al. Acute focal neurological deficits in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: relation of clinical course, CT findings, and metabolite abnormalities monitored with bedside microdialysis. Stroke. 2003;34:1382–8.

Helbok R, Madineni RC, Schmidt MJ, et al. Intracerebral monitoring of silent infarcts after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2011;14:162–7.

Hunt WE, Hess RM. Surgical risk as related to time of intervention in the repair of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1968;28:14–20.

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–29.

Claassen J, Bernardini GL, Kreiter K, et al. Effect of cisternal and ventricular blood on risk of delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the Fisher scale revisited. Stroke. 2001;32:2012–20.

Claassen J, Carhuapoma JR, Kreiter KT, Du EY, Connolly ES, Mayer SA. Global cerebral edema after subarachnoid hemorrhage: frequency, predictors, and impact on outcome. Stroke. 2002;33:1225–32.

Hijdra A, Brouwers PJ, Vermeulen M, van Gijn J. Grading the amount of blood on computed tomograms after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1990;21:1156–61.

Steiner T, Juvela S, Unterberg A, et al. European Stroke Organization guidelines for the management of intracranial aneurysms and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;35:93–112.

Connolly ES Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43:1711–37.

Vergouwen MD, Vermeulen M, van Gijn J, et al. Definition of delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage as an outcome event in clinical trials and observational studies: proposal of a multidisciplinary research group. Stroke. 2010;41:2391–5.

Bellander BM, Cantais E, Enblad P, et al. Consensus meeting on microdialysis in neurointensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:2166–9.

Fainardi E, Tagliaferri MF, Compagnone C, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow levels as measured by xenon-CT in vascular territorial low-density areas after subarachnoid hemorrhage are not always ischemic. Neuroradiology. 2006;48:685–90.

Zetterling M, Hallberg L, Hillered L, Karlsson T, Enblad P, Ronne Engstrom E. Brain energy metabolism in patients with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage and global cerebral edema. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:1102–10.

Zazulia AR, Videen TO, Powers WJ. Transient focal increase in perihematomal glucose metabolism after acute human intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:1638–43.

Sarrafzadeh AS, Sakowitz OW, Kiening KL, Benndorf G, Lanksch WR, Unterberg AW. Bedside microdialysis: a tool to monitor cerebral metabolism in subarachnoid hemorrhage patients? Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1062–70.

Jacobsen A, Nielsen TH, Nilsson O, Schalen W, Nordstrom CH. Bedside diagnosis of mitochondrial dysfunction in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurol Scand. 2014;130:156–63.

Oddo M, Levine JM, Frangos S, et al. Brain lactate metabolism in humans with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2012;43:1418–21.

Schiefecker AJ, Dietmann A, Beer R, et al. Neuroinflammation is associated with brain extracellular TAU-protein release after spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Curr Drug Targ. 2017;18:1408–16.

Helbok R, Ko SB, Schmidt JM, et al. Global cerebral edema and brain metabolism after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2011;42:1534–9.

Reinstrup P, Stahl N, Mellergard P, Uski T, Ungerstedt U, Nordstrom CH. Intracerebral microdialysis in clinical practice: baseline values for chemical markers during wakefulness, anesthesia, and neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:701–9 (discussion 9–10).

Acknowledgment

Open access funding provided by Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

Funding

This study has received funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under Project Number KLI 375 (to RB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK and RH contributed to study design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, writing, drafting, and revising the article. MG, VR, AJS, BI, AL, and PR contributed to acquisition of data, drafting and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. RB, JFS, BP, CT, and ES contributed to study design, interpretation of data, drafting and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. All authorship criteria have been met, and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report that they do not have any financial or non-financial conflict of interest.

Ethics approval/informed consent

This study has been approved by the institutional ethics committee and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12028_2019_713_MOESM1_ESM.tiff

Supplemental Figure 1 shows mean (± standard deviation) CPP corresponding to CMD parameters assessed in normal-appearing and perilesional brain tissue. There was no difference between groups (p=0.484). CPP = cerebral perfusion pressure; CMD = cerebral microdialysis; (TIFF 1564 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kofler, M., Gaasch, M., Rass, V. et al. The Importance of Probe Location for the Interpretation of Cerebral Microdialysis Data in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Patients. Neurocrit Care 32, 135–144 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-019-00713-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-019-00713-8