Abstract

Background

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TC) is a well-known complication after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and has been rarely described in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Methods

Case report and review of literature.

Results

Here, we report a 73-year-old woman with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) presenting in cardiogenic shock. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TC) was diagnosed by repeated echocardiography. Cardiovascular support by inotropic agents led to hemodynamic stabilization after initiation of levosimendan. Cardiac function fully recovered within 21 days. We performed an in-depth literature review and identified 16 reported patients with TBI and TC. Clinical course and characteristics are discussed in the context of our patient.

Conclusion

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is under-recognized after TBI and may negatively impact outcome if left untreated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TC) is known to occur in patients with severe brain insult. It has been widely described after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH, 1.2–28 %) [1–3]; however, it rarely occurs in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, and traumatic brain injury (TBI) [4]. In medical ICU patients, the incidence ranges between 5.7 and 28 % [5, 6]. Here, we report a case of mild TBI with secondary hematoma progression presenting with severe TC and provide a comprehensive review of all reported TBI cases [7–19].

Case Report

A previously healthy 73-year-old woman was admitted to the trauma ward of our tertiary hospital with mild TBI. On presentation, she was disoriented, had a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 14, and suffered from retrograde amnesia. Neurological examination revealed bilateral gaze-evoked nystagmus, but no other focal neurological deficit and her vital signs were stable. Laboratory workup revealed 0.21 % blood alcohol concentration. Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the brain showed right parieto-occipital and left temporo-parietal skull fractures with an acute subdural hematoma (ASDH) and traumatic SAH over the left hemisphere and a small left frontal hemorrhagic contusion (Fig. 1, Panel A). Six hours later, the patient deteriorated and repeat head-CT showed a significant progression of the left frontal hemorrhage with intraventricular extension and a midline shift of 11 mm (Fig. 1, Panel A). Hematoma evacuation and placement of an external ventricular drain were immediately performed, and the patient was transferred to the neurological intensive care unit. Postoperatively the patient was on norepinephrine (0.073 mcg/kg/min), sufentanil (0.073 mcg/kg/min), and midazolam (6 mcg/kg/min). Within the next 24 h, norepinephrine had to be continuously increased to 0.29 mcg/kg/min to achieve a cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) of >65 mmHg. In addition, dobutamine (6.038 mcg/kg/min), phenylephrine (0.725 mcg/kg/min), and hydrocortisone (1.933 mcg/kg/min, given to treat secondary adrenal insufficiency) were necessary to keep the patient hemodynamically stable.

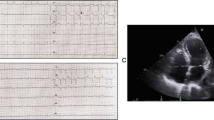

Neuroimaging and echocardiography Panel A indicate axial head computed tomography on admission and at follow-up 6 h later. Echocardiography on day 8 indicates moderate reduction in LVEF secondary to a persisting midventricular and apical hypo-/akinesia (arrows, Panel B). After 21 days (Panel C) LVEF nearly normalized and regional wall motion markedly improved (arrows) consistent with the typical presentation of a takotsubo cardiomyopathy. LV left ventricle, EF ejection fraction

At this time, the electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia at a rate of 130 beats per minute (bpm) with non-specific repolarization abnormalities with no correspondence to a distinct coronary artery territory. Laboratory myocardial biomarkers exceeded pathologic thresholds: Troponin T levels peaked at 0.54 ng/mL (normal range, <0.014 ng/mL) and NT-proBNP was 4690 ng/L (normal range 0–303 ng/L). Creatinine kinase (CK) was within normal range. Bedside transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated severe left ventricular (LV) myocardial dysfunction (ejection fraction 35 %), marked hypokinesia of the apical and midventricular portions of the left ventricle suggestive of takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TC). Only mild mitral regurgitation was detected. Invasive coronary angiography was not performed because of typical findings on echocardiogram and the limited therapeutic possibility due to intracranial bleeding.

As dobutamine was not improving the severe myocardial dysfunction, levosimendan was added (initial dose 0.03 mcg/kg/min, gradually increased to 0.12 mcg/kg/min) and maintained for 28 h. After initiation, no increased dosage of norepinephrine was needed. The heart rate decreased to less than 100 bpm, dobutamine and phenylephrine could be withdrawn, and norepinephrine was slowly decreased over the following days without significant drops in blood pressure. Repeated transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated improvement in LV myocardial function on day 8 (ejection fraction 40 %) (Fig. 1, Panel B) and further recovery on day 21 (Fig. 1, Panel C, ejection fraction 49.9 %, normal 54–74 %). Coronary angiography was not performed as coronary artery disease deemed unlikely due to recovery in cardiac function in repeated echocardiography suggestive for TC as underlying pathology. The patient was successfully weaned on day 11 and discharged for neurorehabilitation 21 days after trauma. At this time, she was fully awake with a GCS score of 15, mildly disabled with a grade 4 brachio-facial left-sided hemiparesis and dysphagia.

Review of Literature

Methods

We performed a comprehensive literature search using the search terms ‘Takotsubo cardiomyopathy,’ ‘Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy,’ ‘stress cardiomyopathy,’ ‘stunned myocardium,’ ‘transient-left-ventricular ballooning syndrome,’ ‘apical ballooning syndrome,’ ‘myocardial dysfunction’ or ‘heart failure’ together with ‘traumatic brain injury,’ ‘head injury,’ and ‘polytrauma.’ Only articles in English language were included.

Results

Overall we identified 13 published articles involving 16 TBI patients with TC [7–19] (Table 1). Among these, 13 were adults and 3 of pediatric age. All patients (except 1 uncharacterized) presented with impaired consciousness necessitating mechanical ventilation. The brain injury pattern was heterogeneous including various degrees of contusional hematoma, epidural hemorrhage (EDH), subdural hemorrhage (SDH), and traumatic SAH with 5 patients undergoing neurosurgical intervention. Six patients presented with polytrauma on admission. TC was diagnosed within 24 h in most patients (N = 10/16, 63 %); however, one patient developed TC 12 days after admission. In 4 patients, coronary angiography was performed and confirmed TC. Electrocardiography abnormalities were found in 9/16 patients (56 %) including ST segment and T wave changes, and 69 % (11/16) had elevated serum troponin levels. Treatment differed; however, most received inotropic support using dobutamine. In one patient, levosimendan at a dose of 0.1 mcg/kg/min was used for 24 h. In addition, various drugs were used to sustain adequate blood pressure including epinephrine, norepinephrine, and vasopressin. Five patients needed extracorporeal life support to treat severe refractory cardiovascular shock. Echocardiography revealed abnormal results in all patients (100 %) and was reversible in the majority of patients within 7 days except in 2 patients after 12 and 17 days, respectively.

In summary, (1) brain injury pattern in TBI patients presenting with TC is heterogeneous and therefore unspecific, (2) in the majority of patients inotropic support using dobutamine leads to improved cardiac function, (3) patients presenting in severe refractory cardiovascular shock may necessitate extracorporeal life support, and (4) with adequate management of TC long-term prognosis is more dependent on the severity of brain injury.

Discussion

Myocardial dysfunction in various degrees has been reported in patients with brain trauma [20–22] (Table 2), being more prevalent in severe TBI. TC represents a serious manifestation of myocardial dysfunction and is defined as an acute, transient, and reversible heart failure syndrome due to regional wall abnormalities of the ventricular myocardium with associated new electrocardiography changes and elevation of myocardial biomarkers in the absence of culprit atherosclerotic coronary artery disease or cardiac condition causing the temporary ventricular dysfunction [23, 24]. Since its’ initial description in 1990, TC was almost exclusively reported in patients with severe SAH. Only a few reports were published in patients with severe TBI although pathophysiologic mechanisms of both entities may have similar effects on the neuro-cardiac axis. Perhaps, many of the earlier suggested criteria to define TC that excluded the presence of TBI had compounded the conundrum [25].

Underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms are still incompletely understood. Most investigations suggest an interconnected cascade of neuronal injury causing sympathetic overstimulation and direct catecholamine toxicity to the heart [26]. Supra-physiologic levels of epinephrine bind to myocardial B2-receptors causing myocardial protein Gs-to-Gi coupling switch, mediated cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) calcium overload in myocytes, and contraction-band necrosis reducing cardiac contractility [27, 28].

Our patient had full recovery of cardiac function 21 days after trauma. Even though transient and reversible in nature, some reports suggest recovery even up to 12-week postinjury [23]. Hemodynamic support is critical in patients with severe TBI based on current treatment concepts that emphasize maintenance of an adequate CPP [29]. Improving cardiac function in patients with TC may be achieved by using dobutamine and other pharmacological, or non-pharmacologic treatment including extracorporeal life support. Our patient failed to improve by using dobutamine at a dose of 6.0 mcg/kg/min. After adding levosimendan, cardiac function and heart rate markedly improved.

Recently, the use of levosimendan has been reported in patients with aneurysmal SAH where dobutamine was deemed ineffective [30]. Levosimendan is a non-catecholamine inodilator used in the treatment of acute heart failure with higher improvement rate in cardiac function compared to dobutamine [31]. It increases the sensitivity of myofilaments to calcium, leading to increased myocardial contraction without increasing intracellular cAMP or calcium concentrations [31]. Through the opening of an ATP-dependent potassium channel, vasodilatory effects in systemic, coronary, pulmonary, and venous blood vessels may be observed [31]. Unlike other vasopressors, it improves myocardial contractility without increasing myocardial oxygen consumption, and more importantly its action is independent of interactions with adrenergic receptors [31]. Nonetheless, its utilization in patients with TC remains scarce, bearing the rarity of the entity itself. In one of the largest case series, levosimendan was successfully used in 13 patients with TC [16].

Conclusions

We highlight the presentation of a patient suffering from TBI with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Although transient in nature and commonly associated with a good overall prognosis, increasing evidence suggests it is a more serious acute cardiac disorder with a variety of complications [23, 24]. Its hemodynamic effect may be deleterious in certain TBI patients if unrecognized. Levosimendan may be an effective therapeutic agent in severe cases.

References

Lee VH, Connolly HM, Fulgham JR, Manno EM, Brown RD Jr, Wijdicks EFM. Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: an under appreciated ventricular dysfunction. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:264–70.

Kilbourn KJ, Levy S, Staff I, Kureshi I, McCullough L. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of neurogenic stress cardiomyopathy in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:909–14.

Banki N, Kopelnik A, Tung P, et al. Prospective analysis of prevalence, distribution, and rate of recovery of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:15–20.

Finsterer J, Wahbi K. CNS disease triggering Takotsubo stress cardiomyopathy: review. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:322–9.

Ruiz-Bailén M, Aguayo-de Hoyos E, López Martinez A, et al. Reversible myocardial dysfunction, a possible complication in critically ill patients without heart disease. J Crit Care. 2003;18:245–52.

Park JH, Kang SJ, Song JK, Kim HK, Lim CM, Kang DH, Koh Y. Left ventricular apical ballooning due to severe physical stress in patients admitted to the medical ICU. Chest. 2005;128:296–302.

Palac RT, Sumner G, Laird R, O’Rourke DJ. Reversible myocardial dysfunction after traumatic brain injury: mechanisms and implications for heart transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2003;13:42–6.

Krishnamoorthy V, Sharma D, Prathep S, Vavilala MS. Myocardial dysfunction in acute traumatic brain injury relieved by surgical decompression. Case Rep Anaesthesiol. 2013;2013:1–4.

Divekar A, Shah S, Joshi C. Neurogenic stunned myocardium and transient severe tricuspid regurgitation in a child following non-accidental head trauma. Pediatr Cardiol. 2006;27(3):376–7.

Deleu D, Kettern MA, Hanssens Y, Kumar S, Salim K, Miyares F. Neurogenic stunned myocardium following hemorrhagic cerebral contusion. Saudi Med J. 2007;28(2):283–5.

Wippermann J, Bennink G, Wittwer T, Madershahian N, Ortmann C, Wahlers T. Reversal of myocardial dysfunction due to brain injury. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2008;16(3):30–1.

Maréchaux S, Goldstein P, Girardie P, Ennezat PV. Contractile pattern of inverted takotsubo cardiomyopathy: illustration by two-dimensional strain. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10(2):332–3.

Vergez M, Pirracchio R, Mateo J, Payen D, Cholley B. Tako tsubo cardiomyopathy in a patient with multiple trauma. Resuscitation. 2009;80(9):1074–7.

Riera M, Llompart-Pou JA, Carillo A, Blanco C. Head injury and inverted takotsubo cardiomyopathy. J Trauma. 2010;68:13–5.

Samol A, Grude M, Stypmann J, et al. Acute global cardiac decompensation due to inverted takotsubo cardiomyopathy after skull-brain trauma- a case report. Injury Extra. 2011;42(5):54–7.

Santoro F, Ieva R, Ferraretti A, et al. Safety and feasibility of levosimendan administration in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a case series. Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;31(6):133–7.

Krpata DM, Barksdle EM Jr. Trauma induced left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome in a 15 year-old: a rare case of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:876–9.

Bonacchi M, Vannini A, Harmelin G, et al. Inverted-takotsubo cardiomyopathy: severe refractory heart failure in poly-trauma patients saved by emergency extracorporeal life support. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015;20(3):365–71.

Hong J, Glater-Welt LB, Siegel LB. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a 23 months-old following traumatic brain injury. Ann Pediatr Child Health. 2014;2(4):1029.

Bahloul M, Chaari AN, Kallel H, et al. Neurogenic pulmonary edema due to traumatic brain injury: evidence of cardiac dysfunction. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15(5):462–70.

Prathep S, Sharma D, Hallman M, et al. Preliminary report on cardiac dysfunction after isolated traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:142–7.

Hasanin A, Kamal A, Amin S, et al. Incidence and outcome of cardiac injury in patients with severe head trauma. Scand J Trauma, Resus Emerg Med. 2016;24:58.

Lyon AR, Bossone E, Schneider B, et al. Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: a position statement from the taskforce on Takotsubo syndrome of the heart failure association of the European society of cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(1):8–27.

Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):929–38.

Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):858–65.

Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):539–48.

Lyon AR, Rees PS, Prasad S, Poole-Wilson PA, Harding SE. Stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy—a novel pathophysiological hypothesis to explain catecholamine-induced acute myocardial stunning. Nat Clin Prac Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:22–9.

Paur H, Wright PT, Sikkel MB, et al. High levels of circulating epinephrine trigger apical cardiodepression in a ß2-adrenergic receptor/Gi–dependent manner: a new model of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2012;126(6):697–706.

Brain Trauma Foundation, American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS), Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS), AANS/CNS Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury, 3rd edition. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(suppl 1):S1–S106.

Taccone FS, Brasseur A, Vincent JL, De Backer D. Levosimendan for the treatment of subarachnoid haemorrhage-related cardiogenic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(8):1497–8.

Parissis JT, Rafouli-Stergiou P, Paraskevaidis I, Mebazaa A. Levosimendan: from basic science to clinical practice. Heart Fail Rev. 2009;14(4):265–75.

Acknowledgments

Paul Rhomberg, MD, Department of Neuroradiology, Medical University of Innsbruck Anichstrasse 35, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria provided neuroimaging data. Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck.

Authors Contribution

Chun Fai Cheah contributed to concept, design, writing, and editing; Mario Kofler helped with design, editing, and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; Alois Schiefecker helped in editing and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; Ronny Beer and Bettina Pfausler contributed to concept, design, and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; Gert Klug helped with echocardiography, data interpretation, and critical revision; Raimund Helbok contributed to idea, writing, reviewing, editing, and critical revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (AVI 3633 kb)

Supplementary material 2 (AVI 3492 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheah, C.F., Kofler, M., Schiefecker, A.J. et al. Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy in Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurocrit Care 26, 284–291 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-016-0334-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-016-0334-y