Abstract

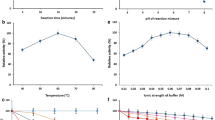

A fungal strain isolated from rotten banana and identified as Aspergillus alliaceus was found capable of producing thermostable extracellular β-galactosidase enzyme. Optimum cultural conditions for β-galactosidase production by A. alliaceus were as follows: pH 4.5; temperature, 30 °C; inoculum age, 25 h; and fermentation time, 144 h. Optimum temperature, time, and pH for enzyme substrate reaction were found to be 45 °C, 20 min, and 7.2, respectively, for crude and partially purified enzyme. For immobilized enzyme–substrate reaction, these three variable, temperature, time, and pH were optimized at 50 °C, 40 min, and 7.2, respectively. Glucose was found to inhibit the enzyme activity. The K m values of partially purified and immobilized enzymes were 170 and 210 mM, respectively. Immobilized enzyme retained 43 % of the β-galactosidase activity of partially purified enzyme. There was no significant loss of activity on storage of immobilized beads at 4 °C for 28 days. Immobilized enzyme retained 90 % of the initial activity after being used four times.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Shukla, T. P. (1975). Beta-galactosidase technology: a solution to the lactose problem. CRC Critical Reviews in Food Technology, 5, 325–356.

Dziezak, J. D. (1991). Enzymes: Catalysts for food processes. Food Technology 45, 78–85.

Godfrey, T. (2000). Developments in speciality enzymes. World Food Ingredients February/March, 30–50.

Pomeranz, Y. (1964). Lactase occurrence and properties. Food Technology, 88, 682.

Wendorff, W. L., et al. (1971). Use of yeast beta-galactosidase in milk and milk products. Journal of Milk Food Technology, 34, 294.

Manjon, A., et al. (1985). Properties of ß-galactosidase covalently immobilized to glycophase-coated porous glass. Process Biochemistry, 20, 17–22.

Gekas, V., & López-Leiva, M. (1985). Hydrolysis of lactose: A literature review. Process Biochemistry, 20, 2–12.

Sarney, D. B., et al. (2000). A novel approach to the recovery of biologically active oligosaccharides from milk using a combination of enzymatic treatment and nanofiltration. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 69(4), 461–467.

Sutendra, G., et al. (2007). beta-Galactosidase (Escherichia coli) has a second catalytically important Mg2+ site. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 352(2), 566–570.

Craig, D. B., et al. (2000). Escherichia coli beta-galactosidase is heterogeneous with respect to a requirement for magnesium. Biometals, 13(3), 223–229.

Polizzi, K. M., et al. (2007). Stability of biocatalysts. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 11(2), 220–225.

Berger, J. L., et al. (1995). Immobilization of beta-galactosidases from Thermus aquaticus Yt-1 for Oligosaccharides Synthesis. Biotechnology Techniques, 9(8), 601–606.

Decleire, M., et al. (1987). Hydrolysis of whey by Kluyveromyces bulgaricus cells immobilized in stabilized alginate and in chitosan beads. Acta Biotechnologica, 7(6), 563–566.

Bommarius, A. S., & Riebel, B. R. (2004). Biocatalysis: fundamentals and applications. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

Carpio, C., et al. (2000). Bone-bound enzymes for food industry application. Food Chemistry, 68(4), 403–409.

Karel, S. F., et al. (1985). The immobilization of whole cells—engineering principles. Chemical Engineering Science, 40(8), 1321–1354.

Longo, M. A., et al. (1992). Diffusion of proteases in calcium alginate beads. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 14(7), 586–590.

Tanriseven, A., & Dogan, S. (2002). A novel method for the immobilization of beta-galactosidase. Process Biochemistry, 38(1), 27–30.

Sneh, B., & Stack, J. (1990). Selective medium for isolation of Mycoleptodiscus terrestris from soil sediments of aquatic environments. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 56(11), 3273–3277.

John, G. H. (1994). Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Romero, F. J., et al. (2001). Production, purification and partial characterization of two extracellular proteases from Serratia marcescens grown in whey. Process Biochemistry, 36(6), 507–515.

Lowry, O. H., et al. (1951). Protein measurement with folin phenol reagent. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 193(1), 265–275.

Banerjee, M., et al. (1982). Immobilization of yeast-cells containing beta-galactosidase. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 24(8), 1839–1850.

Salle, A. J. (1954). Laboratory manual on fundamental principles of bacteriology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Inchaurrondo, V. A., et al. (1994). Yeast growth and beta-galactosidase production during aerobic batch cultures in lactose-limited synthetic medium. Process Biochemistry, 29(1), 47–54.

Artolozaga, M. J., et al. (1998). One step partial purification of beta-D-galactosidase from Kluyveromyces marxianus CDB 002 using STREAMLINE-DEAE. Bioseparation, 7(3), 137–143.

Matheus, A. O. R., & Rivas, N. (2003). Production and partial characterization of beta-galactosidase from Kluyveromyces lactis grown in deproteinized whey. Archivos Latinoamericanos De Nutricion, 53(2), 194–201.

Hewitt, G. M., & Grootwassink, J. W. D. (1984). Simultaneous production of inulase and lactase in batch and continuous cultures of Kluyveromyces fragilis. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 6(6), 263–270.

Ku, M. A., & Hang, Y. D. (1992). Production of yeast lactase from sauerkraut brine. Biotechnology Letters, 14(10), 925–928.

Chen, K. C., et al. (1992). Search method for the optimal medium for the production of lactase by Kluyveromyces fragilis. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 14(8), 659–664.

Menten, L., & Michaelis, M. I. (1913). Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung. Biochemische Zeitschrift, 49, 333–369.

Ping, Z. A., & Butterfield, D. A. (1992). Spin labeling and kinetic-studies of a membrane-immobilized proteolytic-enzyme. Biotechnology Progress, 8(3), 204–210.

Bowen, W. H., & Lawrence, R. A. (2005). Comparison of the cariogenicity of cola, honey, cow milk, human milk, and sucrose. Pediatrics, 116(4), 921–926.

Palumbo, M. S., et al. (1995). Stability of beta-galactosidase from Aspergillus oryzae and Kluyveromyces lactis in dry milk powders. Journal of Food Science, 60(1), 117–119.

Burin, L., & Buera, M. D. (2002). beta-galactosidase activity as affected by apparent pH and physical properties of reduced moisture systems. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 30(3), 367–373.

Van Laere, K. M. J., et al. (2000). Characterization of a novel beta-galactosidase from Bifidobacterium adolescentis DSM 20083 active towards transgalactooligosaccharides. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 66(4), 1379–1384.

Gonzalez, R. R., & Monsan, P. (1991). Purification and some characteristics of beta-galactosidase from Aspergillus fonsecaeus. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 13(4), 349–352.

Hoyoux, A., et al. (2001). Cold-adapted beta-galactosidase from the Antarctic psychrophile Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 67(4), 1529–1535.

Adalberto, P. R., et al. (2010). Effect of divalent metal ions on the activity and stability of β-galactosidase isolated from Kluyveromyces lactis. Journal of Basic and Applied Pharmaceutical Sciences, 31(3), 143–150.

Ansari, S. A., & Husain, Q. (2011). Immobilization of Kluyveromyces lactis beta galactosidase on concanavalin A layered aluminium oxide nanoparticles-Its future aspects in biosensor applications. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 70(3–4), 119–126.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Jadavpur University for financial support for the entire research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sen, S., Ray, L. & Chattopadhyay, P. Production, Purification, Immobilization, and Characterization of a Thermostable β-Galactosidase from Aspergillus alliaceus . Appl Biochem Biotechnol 167, 1938–1953 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-012-9732-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-012-9732-6