Abstract

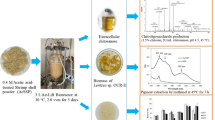

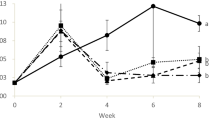

Shrimps have been a popular raw material for the burgeoning marine and food industry contributing to increasing marine waste. Shrimp waste, which is rich in organic compounds is an abundant source of chitin, a natural polymer of N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (GluNac), a reducing sugar. For this respect, chitinase-producing fungi have been extensively studied as biocontrol agents. Locally isolated Trichoderma virens UKM1 was used in this study. The effect of agitation and aeration rates using colloidal chitin as control substrate in a 2-l stirred tank reactor gave the best agitation and aeration rates at 200 rpm and 0.33 vvm with 4.1 U/l per hour and 5.97 U/l per hour of maximum volumetric chitinase activity obtained, respectively. Microscopic observations showed shear sensitivity at higher agitation rate of the above system. The oxygen uptake rate during the highest chitinase productivity obtained using sun-dried ground shrimp waste of 1.74 mg of dissolved oxygen per gram of fungal biomass per hour at the k L a of 8.34 per hour.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sachindra, N. M., & Mahendrakar, N. S. (2005). Process optimization for extraction of carotenoids from shrimp waste with vegetable oils. Bioresearch Technology, 96, 1195–1200.

Coward-Kelly, G., Agbogbo, F. K., & Holtzapple, M. T. (2006). Lime treatment of shrimp head waste for the generation of highly digestible animal feed. Bioresearch Technology, 97, 1515–1520.

Tharanathan, R. N., & Kittur, F. S. (2003). Chitin—The undisputed biomolecule of great potential. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 43(1), 61–87.

Gildberg, A., & Stenberg, E. (2001). A new process for advanced utilisation of shrimp waste. Process Biochemistry, 36(8–9), 809–812.

Yen, Y. H., Li, P. L., Wang, C. L., & Wang, S. L. (2006). An antifungal protease produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa M-1001 with shrimp and crab shell powder as a carbon source. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 39, 311–317.

Liang, T. W., Lin, J. J., Yen, Y. H., Wang, C. L., & Wang, S. L. (2006). Purification and characterization of a protease extracellularly produced by Monascus purpureus CCRC31499 in a shrimp and crab shell powder medium. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 38(1–2), 74–80.

Matsumoto, Y., Saucedo-Castaneda, G., Revah, S., & Shirai, K. (2004). Production of a β-N-acetylhexosaminidase of Verticillium lecanii by solid state and submerged fermentations utilizing shrimp waste silage as substrate and inducer. Process Biochemistry, 39, 665–671.

Wang, S. L., Yen, Y. H., Tzeng, G. C., & Hsieh, C. (2005). Production of antifungal materials by bioconversion of shellfish chitin wastes fermented by Pseudomonas fluorescens K-188. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 36, 49–56.

Wang, S. L., Hsiao, W. J., & Chang, W. T. (2002a). Purification and characterization of an antimicrobial chitinase extracellularly produced by Monascus purpureus CCRC31499 in a shrimp and crab shell powder medium. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 50, 2249–2255.

Lorito, M., diPietro, A., Hayes, C. K., Woo, S. L., & Harman, G. E. (1993). Antifungal, synergistic interaction between chitinolytic enzymes from Trichoderma harzianum and Enterobacter cloacae. Phytopath, 83, 721–728.

Fenton, D. M., & Eveleigh, D. E. (1981). Purification and mode of action of a chitinase from Penicillium islandicus. Journal of General Microbiology, 126, 151–154.

Rose, M. D., Winston, F., & Hieter, P. (1990). Methods in yeast genetics: A laboratory course manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

Aloise, P. A., Lumme, M., & Aynes C. A. (1996). N-Acetyl-d-glucosamine production from chitin-waste using chitinases from Serratia marcescens. In: R.A.A. Muzzarelli (Ed.). Chitin Enzymology, 2, 581–594.

Usui, T., Hayashi, Y., Nanjo, F., Sakai, K., & Ishido, Y. (1987). Transglycosylation reaction of a chitinase purified from Nocardia orientalis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 923, 302–309.

Duo-Chuan, L. (2006). Review of fungal chitinases. Mycopathologia, 161, 345–360.

De La Cruz, J., Hidalgo-Gallego, A., Lora, J. M., Benitez, T., & Pintor-Toro, J. A. (1992). Isolation and characterization of three chitinases from Trichoderma harzianum. European Journal of Biochemistry, 206, 859–867.

Gokul, B., Lee, J. H., Song, K. B., Rhee, S. K., Kim, C. H., & Panda, T. (2000). Characterization and applications of chitinases from Trichoderma harzianum. Bioprocess Engineering, 23, 691–694.

Felse, P. A., & Panda, T. (2000). Submerged culture production of chitinase by Trichoderma harzianum in stirrer tank bioreactors—The influence of agitator speed. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 4, 115–120.

Kawachi, I., Fujieda, T., Ujita, M., Ishii, Y., Yamagishi, K., Sato, H., et al. (2001). Purification and properties of extracellular chitinases from the parasitic Fungus Isaria japonica. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 92, 554–549.

Shuler, M. L., & Kargi, F. (2002). Bioprocess engineering basic concepts (2nd ed.). USA: Prentice Hall.

Badino Jr, A. C., Facciotti, A. C. R., & Schmidell, W. (2000). Improving kLa determination in fungal fermentation, taking into account electrode response time. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology, 75, 469–474.

Lowry, O. H., Rosebrough, N. J., Farr, A. L., & Randall, R. J. (1951). Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 193, 265–275.

Rojas-Avelizapa, L. I., Cruz-Camarillo, R., Guerrero, M. I., Rodriguez-Vazquez, R., & Ibarra, J. E. (1999). Selection and characterization of a proteo-chitinolytic strain of Bacillus thuringiensis, able to grow in shrimp waste media. World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology, 15(2), 261–268.

Gomez-Ramirez, M., Rojas-Avelizapa, L. I., Rojas-Avelizapa, N. G., & Cruz-Camarillo, R. (2004). Colloidal chitin stained with remazol brilliant blue R, a useful substrate to select chitinolytic microorganisms and to evaluate chitinases. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 56, 213–219.

Scopes, R. K. (1994). Protein purification principles and practice (3rd ed.). USA: Springer.

Bailey, J. E., & Ollis, D. F. (1986). Biochemical engineering fundamentals (2nd ed.). Singapore: McGraw-Hill International Editions.

Amanullah, A., Blair, R., Nienow, A. W., & Thomas, C. R. (1999). Effects of agitation intensity on mycelia morphology and protein production in chemostat cultures of recombinant Aspergillus oryzae. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 62, 434–446.

Amanullah, A., Christensen, L. H., Hansen, K., Nienow, A. W., & Thomas, C. R. (2002). Dependence of morphology on agitation intensity in fed-batch cultures of Aspergillus oryzae and its implications for recombinant protein production. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 77, 815–826.

Cui, Y. Q., Okkerse, W. J., van der Lans, R. G. J. M., & Luyben, K. C. H. A. M. (1998a). Modeling and measuring of fungal growth and morphology in submerged fermentations. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 60, 216–229.

Cui, Y. Q., van der Lans, R. G. J. M., Giuseppin, M. L. F., & Luyben, K. C. H. A. M. (1998b). Influence of fermentation conditions and scale on the submerged fermentation of Aspergillus awamori. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 23, 157–167.

Li, Z. J., Shukla, V., Wenger, K. S., Fordyce, A. P., Pedersen, A. G., & Marten, M. R. (2002). Effects of increased impeller power in a production-scale Aspergillus oryzae fermentation. Biotechnology Progress, 18, 437–444.

Rast, D. M., Baumgartner, D., Mayer, C., & Hollenstein, G. O. (2003). Cell wall-associated enzymes in fungi. Phytochemistry, 64, 339–366.

Ulhoa, C. J., & Peberdy, J. F. (1991). Purification and characterization of an extracellular chitobiase from Trichoderma Harzianum. Current Microbiology, 23, 285–289.

Papagianni, M. (2004). Fungal morphology and metabolite production in submerged mycelial processes. Biotechnology Advances, 22, 189–259.

Cui, Y. Q., van der Lans, R. G. J. M., & Luyben, K. C. H. A. M. (1997a). Effect of agitation intensities on fungal morphology of submerged fermentation. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 55, 715–726.

Cui, Y. Q., van der Lans, R. G. J. M., & Luyben, K. C. H. A. M. (1997b). Effects of dissolved oxygen tension and mechanical forces on fungal morphology in submerged fermentation. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 57, 409–419.

Wongwicharn, A., McNeil, B., & Harvey, L. M. (1999). Effect of oxygen enrichment on morphology, growth, and heterologous protein production in chemostat cultures of Aspergillus niger B1-D. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 65, 416–424.

Wikipedia (Chlamydospore) online encyclopaedia. Retrieved March 15, 2007 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chlamydospore.

Zhuang, J. H., Gao, Z. G., Liu, X., Chen, J., Yang, Y., & Huang, Y. Q. (2005). Effect of fermentation factors on spore types of Trichoderma strain 23. Chinese Journal of Biological Control, 21(1), 37–40.

Li, L., Qu, Q., Tian, B., & Zhang, K. Q. (2005). Induction of chlamydospores in Trichoderma harzianum and Gliocladium roseum by antifungal compounds produced by Bacillus subtilis C2. Phytopathology, 153, 686–693.

Finkelstein, D. B., & Ball, C. (1992). Biotechnology of filamentous fungi technology and products. USA: Butterworth–Heinemann.

Schumpe, A. (1993). The estimation of gas solubilities in salt solutions. Chemical Engineering Science, 48(1), 153–158.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledged the financial support from the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Malaysia (MOSTI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abd-Aziz, S., Fernandez, C.C., Salleh, M.M. et al. Effect of Agitation and Aeration Rates on Chitinase Production Using Trichoderma virens UKM1 in 2-l Stirred Tank Reactor. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 150, 193–204 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-008-8140-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-008-8140-4