Opinion statement

The high rate of nonresponse to cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has remained nearly unchanged since the treatment was introduced. We believe that this is directly related to the many persisting unknowns regarding the mechanical function of asynchronous hearts and the use of electrical stimulation to counteract the deleterious effects of that asynchrony. As a consequence, the key questions pertaining to the pre-implant, intra-implant, and postimplant phases remain unanswered or only partially answered. QRS duration is an imperfect selection criterion, as it does not discriminate the activation pattern. The inclusion of QRS morphology in the international professional practice guidelines is an important first step toward increasing the yield of this therapy. The invasive and the noninvasive electrical mapping techniques seem highly promising and need to be tested in large trials. The site of stimulation is a key element of the response to CRT; additional research must be pursued in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Abraham WT, Fisher WG, Smith AL, et al. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1845–53.

Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2140–50.

Cleland JGF, Daubert J-C, Erdmann E, et al. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1539–49.4.

Cazeau S, Ritter P, Bakdach S, et al. Four chamber pacing in dilated cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1994;17:1974–9.

Cazeau S, Ritter P, Lazarus A, et al. Multisite pacing for end-stage heart failure: early experience. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1996;19:1748–57.

Kass DA. Cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:35–41.

Kass DA. Pathobiology of cardiac dyssynchrony and resynchronization. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1660–5.

Strik M, Regoli F, Auricchio A, et al. Electrical and mechanical ventricular activation during left bundle branch block and resynchronization. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5:117–26.

Exner DV, Auricchio A, Singh JP. Contemporary and future trends in cardiac resynchronization therapy to enhance response. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:27–35.

Prinzen FW, Augustijn CH, Arts T, et al. Redistribution of myocardial fiber strain and blood flow by asynchronous activation. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:300–8.

Prinzen FW, Hunter WC, Wyman BT, et al. Mapping of regional myocardial strain and work during ventricular pacing: experimental study using magnetic resonance imaging tagging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1735–42. This important article describes the impact of dyssynchronous-induced regional load variations on regional ventricular strain.

Barth AS, Chakir K, Kass DA, et al. Transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome in dyssynchronous heart failure and CRT. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5:180–7.

Auricchio A, Fantoni C, Regoli F, et al. Characterization of left ventricular activation in patients with heart failure and left bundle-branch block. Circulation. 2004;109:1133–9. This article describes the typical activation sequence associated with left bundle branch block.

Kass DA, Chen CH, Curry C, et al. Improved left ventricular mechanics from acute VDD pacing in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and ventricular conduction delay. Circulation. 1999;99:1567–73.

Gasparini M, Bocchiardo M, Lunati M, et al. Comparison of 1-year effects of left ventricular and biventricular pacing in patients with heart failure who have ventricular arrhythmias and left bundle-branch block: the Bi vs Left Ventricular Pacing: an International Pilot Evaluation on Heart Failure Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias (BELIEVE) multicenter prospective randomized pilot study. Am Heart J. 2006;152:155–7.

Thibault B, Ducharme A, Harel F, et al. Left ventricular versus simultaneous biventricular pacing in patients withheart failure and a QRS complex >/=120 milliseconds. Circulation. 2011;124:2874–81.

Lumens J, Ploux S, Strik M, et al. Comparative electromechanical and hemodynamic effects of left ventricular and biventricular pacing in dyssynchronous heart failure: electrical resynchronization versus left-right ventricular interaction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2395–403.

Bax JJ, Abraham T, Barold SS, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy: part1—issues before device implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:2153–67.

Gorcsan J III, Yu CM, Sanderson JE. Ventricular resynchronization is the principle mechanism of benefit with cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;17:737–46.

Bleeker GB, Mollema SA, Holman ER, et al. Left ventricular resynchronization is mandatory for response to cardiac resynchronization therapy: analysis in patients with echocardiographic evidence of left ventricular dyssynchrony at baseline. Circulation. 2007;116:1440–8.

Chung ES, Leon AR, Tavazzi L, et al. Results of the Predictors of Response to CRT (PROSPECT) trial. Circulation. 2008;117:2608–16.

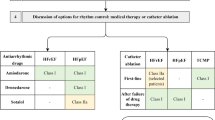

Stevenson WG, Hernandez AF, Carson PE, et al. Indications for cardiac resynchronization therapy: 2011 update from the Heart Failure Society of America guideline committee. J Card Fail. 2012;18:94–106.

Authors/Task Force Members, Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron-Esquivias G, et al. ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: The Task Force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2281–329.

Zareba W, Klein H, Cygankiewicz I, et al. Effectiveness of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy by QRS Morphology in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial-Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT). Circulation. 2011;123:1061–72.

Sipahi I, Chou JC, Hyden M, et al. Effect of QRS morphology on clinical event reduction with cardiac resynchronization therapy: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2012;163:260–7.

Fantoni C, Kawabata M, Massaro R, et al. Right and left ventricular activation sequence in patients with heart failure and right bundle branch block: a detailed analysis using three-dimensional nonfluoroscopic electroanatomic mapping system. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:112–9.

Ploux S, Lumens J, Whinnett Z, et al. Noninvasive electrocardiographic mapping to improve patient selection for cardiac resynchronization therapy: beyond QRS duration and left bundle branch block morphology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2435–43.

Leenders GE, Lumens J, Cramer MJ, et al. Septal deformation patterns delineate mechanical dyssynchrony and regional differences in contractility: analysis of patient data using a computer model. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:87–96.

Lumens J, Leenders GE, Cramer MJ, et al. Mechanistic evaluation of echocardiographic dyssynchrony indices: patient data combined with multiscale computer simulations. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:491–9.

Singh JP, Abraham WT. Enhancing the response to cardiac resynchronization therapy: is it time to individualize the left ventricular pacing site? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:576–8.

Singh JP, Klein HU, Huang DT, et al. Left ventricular lead position and clinical outcome in the multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial-cardiac resynchronization therapy (MADIT-CRT) trial. Circulation. 2011;123:1159–66.

Gold MR, Birgersdotter-Green U, Singh JP, et al. The relationship between ventricular electrical delay and left ventricular remodelling with cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2516–24.

Derval N, Steendijk P, Gula LJ, et al. Optimizing hemodynamics in heart failure patients by systematic screening of left ventricular pacing sites: the lateral left ventricular wall and the coronary sinus are rarely the best sites. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:566–75. This study demonstrates the hemodynamic impact of different pacing sites in patients with primitive cardiomyopathy.

White JA, Yee R, Yuan X, et al. Delayed enhancement magnetic resonance imaging predicts response to cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with intraventricular dyssynchrony. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1953–60.

Bleeker GB, Kaandorp TA, Lamb HJ, et al. Effect of posterolateral scar tissue on clinical and echocardiographic improvement after cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2006;113:969–76.

Khan FZ, Virdee MS, Palmer CR, et al. Targeted left ventricular lead placement to guide cardiac resynchronization therapy: the TARGET study: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1509–18.

Saba S, Marek J, Schwartzman D, et al. Echocardiography-guided left ventricular lead placement for cardiac resynchronization therapy: results of the Speckle Tracking Assisted Resynchronization Therapy for Electrode Region trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:427–34.

Singh JP, Fan D, Heist EK, et al. Left ventricular lead electrical delay predicts response to cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1285–92.

Duckett SG, Ginks M, Shetty AK, et al. Invasive acute hemodynamic response to guide left ventricular lead implantation predicts chronic remodeling in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1128–36.

Bogaard M, Houthuizen P, Bracke F, et al. Baseline left ventricular dP/dtmax rather than the acute improvement in dP/dtmax predicts clinical outcome in patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1126–3.

Whinnett ZI, Francis DP, Denis A, et al. Comparison of different invasive hemodynamic methods for AV delay optimization in patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy: implications for clinical trial design and clinical practice. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2228–37.

Prinzen FW, Auricchio A. The “missing” link between acute hemodynamic effect and clinical response. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5:188–95.

van Deursen C, van Geldorp IE, Rademakers LM, et al. Left ventricular endocardial pacing improves resynchronization therapy in canine left bundle-branch hearts. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:580–7.

Spragg DD, Dong J, Fetics BJ, et al. Optimal left ventricular endocardial pacing sites for cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:774–81. This study demonstrates the hemodynamic impact of different pacing sites in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy.

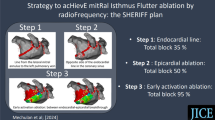

Bordachar P, Derval N, Ploux S, et al. Left ventricular endocardial stimulation for severe heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:747–53.

Bordachar P, Grenz N, Jais P, et al. Left ventricular endocardial or triventricular pacing to optimize cardiac resynchronization therapy in a chronic canine model of ischemic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:207–15.

Leclercq C, Gadler F, Kranig W, et al. A randomized comparison of triple-site versus dual-site ventricular stimulation in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1455–62.

Bordachar P, Alonso C, Anselme F, et al. Addition of a second LV pacing site in CRT nonresponders rationale and design of the multicenter randomized V(3) trial. J Card Fail. 2010;16:709–13.

Auricchio A, Stellbrink C, Block M, et al. Effect of pacing chamber and atrioventricular delay on acute systolic function of paced patients with congestive heart failure. The Pacing Therapies for Congestive Heart Failure Study Group. The Guidant Congestive Heart Failure Research Group. Circulation. 1999;99:2993–3001.

Whinnett ZI, Davies JE, Willson K, et al. Haemodynamic effects of changes in atrioventricular and interventricular delay in cardiac resynchronisation therapy show a consistent pattern: analysis of shape, magnitude and relative importance of atrioventricular and interventricular delay. Heart. 2006;92:1628–34.

van Gelder BM, Bracke FA, Meijer, et al. Effect of optimizing the VV interval on left ventricular contractility in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1500–3.

Van Geldorp I, Delhaas T, Hermans B, et al. Comparison of a noninvasive arterial pulse contour technique and echo Doppler aorta velocity time-integral on stroke volume changes in optimization of CRT. Europace. 2011;13:87–95.

Sawhney NS, Waggoner AD, Garhwal S, et al. Randomized prospective trial of atrioventricular delay programming for cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1:562–7.

Ellenbogen KA, Gold MR, Meyer TE, et al. Primary results from the SmartDelay determined AV optimization: a comparison to other AV delay methods used in cardiac resynchronization therapy (SMART-AV) trial: a randomized trial comparing empirical, echocardiography-guided, and algorithmic atrioventricular delay programming in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2010;122:2660–8.

Martin DO, Lemke B, Birnie D, Adaptive CRT Study Investigators, et al. Investigation of a novel algorithm for synchronized left-ventricular pacing and ambulatory optimization of cardiac resynchronization therapy: results of the adaptive CRT trial. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1807–14.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Pierre Bordachar, Dr. Romain Eschalier, Dr. Joost Lumens, and Dr. Sylvain Ploux each declare no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Arrhythmia

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bordachar, P., Eschalier, R., Lumens, J. et al. Optimal Strategies on Avoiding CRT Nonresponse. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 16, 299 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-014-0299-0

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-014-0299-0