Abstract

Purpose of Review

A better understanding of suicide phenomena is needed, and precision medicine is a promising approach toward this aim. In this manuscript, we review recent advances in the field, with particular focus on the role of digital health.

Recent Findings

Technological advances such as smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment and passive collection of information from sensors provide a detailed description of suicidal behavior and thoughts. Further, we review more traditional approaches in the field of genetics.

Summary

We first highlight the need for precision medicine in suicidology. Then, in light of recent and promising research, we examine the role of smartphone-based information collection using explicit (active) and implicit (passive) means to construct a digital phenotype, which should be integrated with genetic and epigenetic data to develop tailored therapeutic and preventive approaches for suicide.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Silverman MM, Pirkis JE, Pearson JL, Sherrill JT. Reflections on expert recommendations for US research priorities in suicide prevention. Am J Prevent Med. 2014;47:S97–S101.

Saxena S, Krug EG, Chestnov O, World Health Organization, editors. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Lee L, Roser M, Ortiz-Ospina E. Suicide [Internet]. Our World in Data. 2018 [cited 2018 Dec 9]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/suicide

Products - Data Briefs - Number 241 - April 2016 [Internet]. [cited 2017 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db241.htm

Large M, Sharma S, Cannon E, Ryan C, Nielssen O. Risk factors for suicide within a year of discharge from psychiatric hospital: a systematic meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45:619–28.

Large M, Smith G, Sharma S, Nielssen O, Singh SP. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical factors associated with the suicide of psychiatric in-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:18–29.

Chan MKY, Bhatti H, Meader N, Stockton S, Evans J, O’Connor RC, et al. Predicting suicide following self-harm: systematic review of risk factors and risk scales. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:277–83.

• Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin. 2017;143:187–232 This meta-analysis critically reviews 50 years of research in suicide factor risk study.

Schaffer A, Isometsä ET, Azorin J-M, Cassidy F, Goldstein T, Rihmer Z, et al. A review of factors associated with greater likelihood of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in bipolar disorder: part II of a report of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide in Bipolar Disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1006–20.

Glenn CR, Nock MK. Improving the short-term prediction of suicidal behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:S176–80.

• Torous J, Larsen ME, Depp C, Cosco TD, Barnett I, Nock MK, et al. Smartphones, sensors, and machine learning to advance real-time prediction and interventions for suicide prevention: a review of current progress and next steps. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20:51. This paper is a revision of technological advances in suicide assessment and prevention.

Mulder R, Newton-Howes G, Coid JW. The futility of risk prediction in psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:271–2.

Reference GH. What is the precision medicine initiative? [Internet]. Genetics Home Reference. [cited 2018 Dec 16]. Available from: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/precisionmedicine/initiative

National Research Council (US) Committee on A Framework for Developing a New Taxonomy of Disease. Toward precision medicine: building a knowledge network for biomedical research and a new taxonomy of disease [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011 [cited 2018 Dec 8]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK91503/

Ozomaro U, Wahlestedt C, Nemeroff CB. Personalized medicine in psychiatry: problems and promises. BMC Med. 2013;11:132.

• Beckmann JS, Lew D. Reconciling evidence-based medicine and precision medicine in the era of big data: challenges and opportunities. Genome Medicine. 2016;8:134. This paper focuses on the importance of a collaborative approach in precision medicine.

Schork NJ. Personalized medicine: time for one-person trials. Nature News. 2015;520:609.

Lilienfeld SO, Treadway MT. Clashing diagnostic approaches: DSM-ICD versus RDoC. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12:435–63.

Fraguas D, Díaz-Caneja CM, State MW, O’Donovan MC, Gur RE, Arango C. Mental disorders of known aetiology and precision medicine in psychiatry: a promising but neglected alliance. Psychol Med. 2017;47:193–7.

Oquendo MA, Baca-García E, Mann JJ, Giner J. Issues for DSM-V: suicidal behavior as a separate diagnosis on a separate axis. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1383–4.

Oquendo MA, Baca-Garcia E. Suicidal behavior disorder as a diagnostic entity in the DSM-5 classification system: advantages outweigh limitations. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:128–30.

• Insel TR. The NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Project: precision medicine for psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:395–7. This paper proposes RDoC as a valid approach to precision medicine in psychiatry.

NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) [Internet]. [cited 2018 Dec 8]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/rdoc/index.shtml

Torous J, Onnela J-P, Keshavan M. New dimensions and new tools to realize the potential of RDoC: digital phenotyping via smartphones and connected devices. Translational Psychiatry. 2017;7.

Bidargaddi N, Musiat P, Makinen V-P, Ermes M, Schrader G, Licinio J. Digital footprints: facilitating large-scale environmental psychiatric research in naturalistic settings through data from everyday technologies. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:164–9.

Poushter J. Smartphone ownership and Internet usage continues to climb in emerging economies [Internet]. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. 2016 [cited 2018 May 27]. Available from: http://www.pewglobal.org/2016/02/22/smartphone-ownership-and-internet-usage-continues-to-climb-in-emerging-economies/

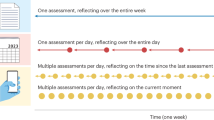

• Kleiman EM, Turner BJ, Fedor S, Beale EE, Huffman JC, Nock MK. Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. J Abnorm Psychol. 2017;126:726–38 This is one of the six recent studies using smartphone-based EMA in the study of suicide.

Bernanke JA, Stanley BH, Oquendo MA. Toward fine-grained phenotyping of suicidal behavior: the role of suicidal subtypes. Molecular Psychiatry. 2017;22:1080–1.

Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32.

Csikszentmihalyi M, Larson R. Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175:526–36.

Husky M, Swendsen J, Ionita A, Jaussent I, Genty C, Courtet P. Predictors of daily life suicidal ideation in adults recently discharged after a serious suicide attempt: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:79–84.

van Os J, Verhagen S, Marsman A, Peeters F, Bak M, Marcelis M, et al. The experience sampling method as an mHealth tool to support self-monitoring, self-insight, and personalized health care in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34:481–93.

Berrouiguet S, Ramírez D, Barrigón ML, Moreno-Muñoz P, Camacho RC, Baca-García E, et al. Combining continuous smartphone native sensors data capture and unsupervised data mining techniques for behavioral changes detection: a case series of the Evidence-Based Behavior (eB2) Study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2018;6:e197.

Insel TR. Digital phenotyping: technology for a new science of behavior. JAMA. 2017;318:1215.

Davidson CL, Anestis MD, Gutierrez PM. Ecological momentary assessment is a neglected methodology in suicidology. Arch Suicide Res. 2016:1–11.

Husky M, Olié E, Guillaume S, Genty C, Swendsen J, Courtet P. Feasibility and validity of ecological momentary assessment in the investigation of suicide risk. Psychiatry Research. 2014;220:564–70.

Law MK, Furr RM, Arnold EM, Mneimne M, Jaquett C, Fleeson W. Does assessing suicidality frequently and repeatedly cause harm? A randomized control study. Psychol Assess. 2015;27:1171–81.

We’re more honest with our phones than with our doctors. The New York Times [Internet]. 2016 Mar 23 [cited 2016 Apr 21]; Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/03/26/magazine/100000004288446.embedded.html

Barak A. Emotional support and suicide prevention through the Internet: a field project report. Computers in Human Behavior. 2007;23:971–84.

Bennett GG, Glasgow RE. The delivery of public health interventions via the Internet: actualizing their potential. Annual Review of Public Health. 2009;30:273–92.

Torous J, Staples P, Shanahan M, Lin C, Peck P, Keshavan M, et al. Utilizing a personal smartphone custom app to assess the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. JMIR Ment Health. 2015;2:e8.

Barrigón ML, Berrouiguet S, Carballo JJ, Bonal-Giménez C, Fernández-Navarro P, Pfang B, et al. User profiles of an electronic mental health tool for ecological momentary assessment: MEmind. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26.

Palmier-Claus JE, Ainsworth J, Machin M, Dunn G, Barkus E, Barrowclough C, et al. Affective instability prior to and after thoughts about self-injury in individuals with and at-risk of psychosis: a mobile phone based study. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17:275–87.

• Kleiman EM, Turner BJ, Fedor S, Beale EE, Picard RW, Huffman JC, et al. Digital phenotyping of suicidal thoughts. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35:601–8. This is one of the six recent studies using smartphone-based EMA in the study of suicide.

• Kleiman EM, Coppersmith DDL, Millner AJ, Franz PJ, Fox KR, Nock MK. Are suicidal thoughts reinforcing? A preliminary real-time monitoring study on the potential affect regulation function of suicidal thinking. J Affect Disord. 2018;232:122–6. This is one of the six recent studies using smartphone-based EMA in the study of suicide.

• Hallensleben N, Spangenberg L, Forkmann T, Rath D, Hegerl U, Kersting A, et al. Investigating the dynamics of suicidal ideation. Crisis. 2018;39:65–9. This is one of the six recent studies using smartphone-based EMA in the study of suicide.

• Czyz EK, King CA, Nahum-Shani I. Ecological assessment of daily suicidal thoughts and attempts among suicidal teens after psychiatric hospitalization: lessons about feasibility and acceptability. Psychiatry Res. 2018;267:566–74. This is one of the six recent studies using smartphone-based EMA in the study of suicide.

• Hallensleben N, Glaesmer H, Forkmann T, Rath D, Strauss M, Kersting A, et al. Predicting suicidal ideation by interpersonal variables, hopelessness and depression in real-time. An ecological momentary assessment study in psychiatric inpatients with depression. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;56:43–50. This is one of the six recent studies using smartphone-based EMA in the study of suicide.

• Kleiman EM, Nock MK. Real-time assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2018;22:33–7. This paper is a revision of technological advances in suicide assessment.

Torous J, Onnela J-P, Keshavan M. New dimensions and new tools to realize the potential of RDoC: digital phenotyping via smartphones and connected devices. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1053.

• Reinertsen E, Clifford GD. A review of physiological and behavioral monitoring with digital sensors for neuropsychiatric illnesses. Physiol Meas. 2018;39:05TR01. This is a comprehensive review of recent studies using sensors for monitoring neuropsychiatric illnesses.

Palmius N, Tsanas A, Saunders KEA, Bilderbeck AC, Geddes JR, Goodwin GM, et al. Detecting bipolar depression from geographic location data. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2017;64:1761–71.

Schueller SM, Begale M, Penedo FJ, Mohr DC. Purple: a modular system for developing and deploying behavioral intervention technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e181.

Torous J, Kiang MV, Lorme J, Onnela J-P. New tools for new research in psychiatry: a scalable and customizable platform to empower data driven smartphone research. JMIR Mental Health. 2016;3:e16.

Evidence-Based Behavior [Internet]. Evidence-based behavior. [cited 2018 Dec 22]. Available from: https://eb2.tech/

Ben-Zeev D, Scherer EA, Brian RM, Mistler LA, Campbell AT, Wang R. Use of multimodal technology to identify digital correlates of violence among inpatients with serious mental illness: a pilot study. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68:1088–92.

Wang F, Chen C. On data processing required to derive mobility patterns from passively-generated mobile phone data. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 2018;87:58–74.

• Barnett I, Torous J, Staples P, Keshavan M, Onnela J-P. Beyond smartphones and sensors: choosing appropriate statistical methods for the analysis of longitudinal data. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25:1669–74. Here, authors highlight the importance of data analyses.

Peis-Aznarte I, Olmos PM. Vera-Varela C. Barrigón ML: Courtet P, Baca-Garcia E, et al. Deep sequential models for suicidal ideation from multiple source data. Enviado para publicación; 2018.

Oquendo MA, Sullivan GM, Sudol K, Baca-Garcia E, Stanley BH, Sublette ME, et al. Toward a biosignature for suicide. AJP. 2014;171:1259–77.

Turecki G. The molecular bases of the suicidal brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:802–16.

Lutz P-E, Mechawar N, Turecki G. Neuropathology of suicide: recent findings and future directions. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:1395–412.

Turecki G, Brent DA. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. The Lancet. 2016;387:1227–39.

O’Connor RC, Portzky G. Looking to the future: a synthesis of new developments and challenges in suicide research and prevention. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Dec 22];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02139/full

• Niculescu AB, Le-Niculescu H, Levey DF, Phalen PL, Dainton HL, Roseberry K, et al. Precision medicine for suicidality: from universality to subtypes and personalization. Molecular Psychiatry. 2017;22:1250–73 This paper provides an approach to precision medicine in suicide from genetics.

The Emory Healthy Aging Study | Emory University [Internet]. Emory | Healthy Aging Study. [cited 2018 Dec 23]. Available from: https://healthyaging.emory.edu/

McKernan LC, Clayton EW, Walsh CG. Protecting life while preserving liberty: ethical recommendations for suicide prevention with artificial intelligence. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Dec 23];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00650/full

Broderick JE, Schwartz JE, Shiffman S, Hufford MR, Stone AA. Signaling does not adequately improve diary compliance. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:139–48.

Funding

This work was partially funded through ANR (the French National Research Agency) under the “Investissements d’avenir” programme with the reference ANR-16-IDEX-0006, Carlos III (ISCIII PI16/01852), American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (LSRG-1-005-16), Structural Funds of the European Union, MINECO/FEDER (“ADVENTURE”, id. TEC2015-69868-C2-1-R), and MCIU Explora Grant “AMBITION” (id. TEC2017-92552-EXP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Maria Luisa Barrigon reports grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, and from Structural Funds of the European Union, MINECO/FEDER.

Philippe Courtet reports grants from American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, grants and personal fees from Fondamental Foundation, and personal fees from Janssen.

Maria Oquendo receives royalties for the commercial use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale, and Dr. Oquendo’s family owns stock in Bristol Myers Squibb.

Enrique Baca-García reports grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, and from Structural Funds of the European Union, MINECO/FEDER.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Precision Medicine in Psychiatry

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barrigon, M.L., Courtet, P., Oquendo, M. et al. Precision Medicine and Suicide: an Opportunity for Digital Health. Curr Psychiatry Rep 21, 131 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1119-8

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1119-8