Abstract

Purpose of Review

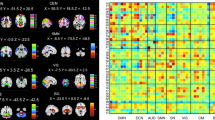

Although a fine-grained understanding of the neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is yet to be elucidated, the last two decades have seen a rapid growth in the study of PTSD using neuroimaging techniques. The current review summarizes important findings from functional and structural neuroimaging studies of PTSD, by primarily focusing on their relevance towards an emerging network-based neurobiological model of the disorder.

Recent Findings

PTSD may be characterized by a weakly connected and hypoactive default mode network (DMN) and central executive network (CEN) that are putatively destabilized by an overactive and hyperconnected salience network (SN), which appears to have a low threshold for perceived saliency, and inefficient DMN-CEN modulation.

Summary

There is considerable evidence for large-scale functional and structural network dysfunction in PTSD. Nevertheless, several limitations and gaps in the literature need to be addressed in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Association. Washington, D.C.: Amer Psychiatric Pub Incorporated; 2013.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602.

Fulton JJ, Calhoun PS, Wagner HR, Schry AR, Hair LP, Feeling N, et al. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) Veterans: a meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;31:98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.02.003.

• Koch SBJ, Zuiden M, Nawijn L, Frijling JL, Veltman DJ, Olff M. Aberrant resting‐state brain activity in posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta‐analysis and systematic review. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(7):592–605. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22478. This is a meta-analysis and systematic review of resting-state functional neuroimaging findings in PTSD and includes connectivity and activation studies

Hayes JP, Hayes SM, Mikedis AM. Quantitative meta-analysis of neural activity in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2012;2:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-5380-2-9.

Patel R, Spreng RN, Shin LM, Girard TA. Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and beyond: a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(9):2130–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.06.003.

Wang T, Liu J, Zhang J, Zhan W, Li L, Wu M, et al. Altered resting-state functional activity in posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27131. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27131.

Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(10):483–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.08.003.

Pitman RK, Rasmusson AM, Koenen KC, Shin LM, Orr SP, Gilbertson MW, et al. Biological studies of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(11):769–87. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3339.

• Sheynin J, Liberzon I. Circuit dysregulation and circuit-based treatments in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neurosci Lett. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2016.11.014. This recent review describes PTSD abnormalities in terms of threat detection, context-processing, and emotion-regulation circuit dysfunction

• Averill LA, Purohit P, Averill CL, Boesl MA, Krystal JH, Abdallah CG. Glutamate dysregulation and glutamatergic therapeutics for PTSD: Evidence from human studies. Neurosci Lett. 2017;649:147–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2016.11.064. This review focuses on glutamate and GABA neurochemical and receptor imaging in PTSD

Matosin N, Cruceanu C, Binder EB. Preclinical and clinical evidence of DNA methylation changes in response to trauma and chronic stress. Chronic Stress. 2017;1:2470547017710764. https://doi.org/10.1177/2470547017710764.

Krystal JH, Abdallah CG, Averill LA, Kelmendi B, Harpaz-Rotem I, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic loss and the pathophysiology of PTSD: implications for ketamine as a prototype novel therapeutic. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(10):74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0829-z.

• DCM O’D, Chitty KM, Saddiqui S, Bennett MR, Lagopoulos J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging measurement of structural volumes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2015;232(1):1–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.01.002. This is a meta-analysis and systematic review of volumetric structural MRI findings in PTSD

Rauch SL, Shin LM, Phelps EA. Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and extinction: human neuroimaging research—past, present, and future. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):376–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.004.

Yeo BT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106(3):1125–65. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00338.2011.

Sripada RK, King AP, Welsh RC, Garfinkel SN, Wang X, Sripada CS, et al. Neural dysregulation in posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence for disrupted equilibrium between salience and default mode brain networks. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(9):904–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e318273bf33.

Chen AC, Etkin A. Hippocampal network connectivity and activation differentiates post-traumatic stress disorder from generalized anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(10):1889–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.122.

Bluhm RL, Williamson PC, Osuch EA, Frewen PA, Stevens TK, Boksman K, et al. Alterations in default network connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder related to early-life trauma. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009;34(3):187–94.

Akiki T, Averill C, Wrocklage K, Scott JC, Alexander-Bloch A, Southwick S, et al. 581. The default mode network in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a data-driven multimodal approach. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81(10, Supplement):S235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.02.451.

St. Jacques PL, Kragel PA, Rubin DC. Neural networks supporting autobiographical memory retrieval in posttraumatic stress disorder. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2013;13(3):554–66. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-013-0157-7.

Brown VM, LaBar KS, Haswell CC, Gold AL, Mid-Atlantic MW, McCarthy G, et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity of basolateral and centromedial amygdala complexes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(2):351–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.197.

Sanjuan PM, Thoma R, Claus ED, Mays N, Caprihan A. Reduced white matter integrity in the cingulum and anterior corona radiata in posttraumatic stress disorder in male combat veterans: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychiatry Res. 2013;214(3):260–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.09.002.

Kennis Ph DM, van Rooij Ph DS, Reijnen MA, Geuze Ph DE. The predictive value of dorsal cingulate activity and fractional anisotropy on long-term PTSD symptom severity. Depress Anxiety. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22605.

Fani N, King TZ, Jovanovic T, Glover EM, Bradley B, Choi K, et al. White matter integrity in highly traumatized adults with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(12):2740–6.

Fani N, King TZ, Shin J, Srivastava A, Brewster RC, Jovanovic T, et al. Structural and functional connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder: associations with FKBP5. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(4):300–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22483.

Admon R, Leykin D, Lubin G, Engert V, Andrews J, Pruessner J, et al. Stress-induced reduction in hippocampal volume and connectivity with the ventromedial prefrontal cortex are related to maladaptive responses to stressful military service. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34(11):2808–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22100.

Sun Y, Wang Z, Ding W, Wan J, Zhuang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Alterations in white matter microstructure as vulnerability factors and acquired signs of traffic accident-induced PTSD. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83473. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083473.

Meng L, Jiang J, Jin C, Liu J, Zhao Y, Wang W, et al. Trauma-specific grey matter alterations in PTSD. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33748. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33748.

Nardo D, Hogberg G, Looi JC, Larsson S, Hallstrom T, Pagani M. Gray matter density in limbic and paralimbic cortices is associated with trauma load and EMDR outcome in PTSD patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(7):477–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.10.014.

Liu Y, Li YJ, Luo EP, Lu HB, Yin H. Cortical thinning in patients with recent onset post-traumatic stress disorder after a single prolonged trauma exposure. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39025. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039025.

Woodward SH, Schaer M, Kaloupek DG, Cediel L, Eliez S. Smaller global and regional cortical volume in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(12):1373–82. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.160.

Smith ME. Bilateral hippocampal volume reduction in adults with post-traumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of structural MRI studies. Hippocampus. 2005;15(6):798–807. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20102.

Vythilingam M, Luckenbaugh DA, Lam T, Morgan CA 3rd, Lipschitz D, Charney DS, et al. Smaller head of the hippocampus in Gulf War-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2005;139(2):89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.04.003.

Akiki TJ, Averill CL, Wrocklage KM, Schweinsburg B, Scott JC, Martini B, et al. The association of PTSD symptom severity with localized hippocampus and amygdala abnormalities. Chronic Stress. 2017;1:2470547017724069. https://doi.org/10.1177/2470547017724069.

Cisler JM, Steele JS, Smitherman S, Lenow JK, Kilts CD. Neural processing correlates of assaultive violence exposure and PTSD symptoms during implicit threat processing: a network level analysis among adolescent girls. Psychiatry Res. 2013;214(3) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.06.003.

Rabellino D, Tursich M, Frewen PA, Daniels JK, Densmore M, Theberge J, et al. Intrinsic Connectivity Networks in post-traumatic stress disorder during sub- and supraliminal processing of threat-related stimuli. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(5):365–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12418.

Li L, Lei D, Li L, Huang X, Suo X, Xiao F, et al. White matter abnormalities in post-traumatic stress disorder following a specific traumatic event. EBioMedicine. 2016;4:176–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.01.012.

Geuze E, Westenberg HG, Heinecke A, de Kloet CS, Goebel R, Vermetten E. Thinner prefrontal cortex in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. NeuroImage. 2008;41(3):675–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.007.

Li L, Wu M, Liao Y, Ouyang L, Du M, Lei D, et al. Grey matter reduction associated with posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;43:163–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.04.003.

Mollica RF, Lyoo I, Chernoff MC, Bui HX, Lavelle J, Yoon SJ, et al. Brain structural abnormalities and mental health sequelae in south Vietnamese ex–political detainees who survived traumatic head injury and torture. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(11):1221–32. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.127.

Wrocklage KM, Averill LA, Cobb Scott J, Averill CL, Schweinsburg B, Trejo M, et al. Cortical thickness reduction in combat exposed U.S. veterans with and without PTSD. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(5):515–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.02.010.

Rabinak CA, Angstadt M, Welsh RC, Kenndy AE, Lyubkin M, Martis B, et al. Altered amygdala resting-state functional connectivity in post-traumatic stress disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:62. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00062.

Pietrzak RH, Averill LA, Abdallah CG, Neumeister A, Krystal JH, Levy I, et al. Amygdala-hippocampal volume and the phenotypic heterogeneity of posttraumatic stress disorder: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):396–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2470.

Kuo JR, Kaloupek DG, Woodward SH. Amygdala volume in combat-exposed veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder: a cross-sectional study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(10):1080–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.73.

Morey RA, Gold AL, LaBar KS, Beall SK, Brown VM, Haswell CC, et al. Amygdala volume changes in posttraumatic stress disorder in a large case-controlled veterans group. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11) https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.50.

Rogers MA, Yamasue H, Abe O, Yamada H, Ohtani T, Iwanami A, et al. Smaller amygdala volume and reduced anterior cingulate gray matter density associated with history of post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2009;174(3):210–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.06.001.

Mueller SG, Ng P, Neylan T, Mackin S, Wolkowitz O, Mellon S, et al. Evidence for disrupted gray matter structural connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2015;234(2):194–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.09.006.

Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.011.

Andrews-Hanna JR, Reidler JS, Sepulcre J, Poulin R, Buckner RL. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain’s default network. Neuron. 2010;65(4):550–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.005.

Chand GB, Dhamala M. Interactions among the brain default-mode, salience, and central-executive networks during perceptual decision-making of moving dots. Brain Connect. 2016;6(3):249–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/brain.2015.0379.

Miller DR, Hayes SM, Hayes JP, Spielberg JM, Lafleche G, Verfaellie M. Default mode network subsystems are differentially disrupted in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2017;2(4):363–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.12.006.

Kishi T, Tsumori T, Yokota S, Yasui Y. Topographical projection from the hippocampal formation to the amygdala: a combined anterograde and retrograde tracing study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2006;496(3):349–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.20919.

Strange BA, Witter MP, Lein ES, Moser EI. Functional organization of the hippocampal longitudinal axis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(10):655–69. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3785.

Wang Z, Neylan TC, Mueller SG, Lenoci M, Truran D, Marmar CR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of hippocampal subfields in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):296–303. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.205.

Abdallah CG, Wrocklage KM, Averill CL, Akiki T, Schweinsburg B, Roy A, et al. Anterior hippocampal dysconnectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder: a dimensional and multimodal approach. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(2):e1045. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2017.12.

Shin LM, Liberzon I. The neurocircuitry of fear, stress, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35(1):169–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.83.

Lazarov A, Zhu X, Suarez-Jimenez B, Rutherford BR, Neria Y. Resting-state functional connectivity of anterior and posterior hippocampus in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;94:15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.06.003.

Vermetten E, Vythilingam M, Southwick SM, Charney DS, Bremner JD. Long-term treatment with paroxetine increases verbal declarative memory and hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(7):693–702.

Bryant RA, Felmingham K, Whitford TJ, Kemp A, Hughes G, Peduto A, et al. Rostral anterior cingulate volume predicts treatment response to cognitive-behavioural therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33(2):142–6.

Dickie EW, Brunet A, Akerib V, Armony JL. Anterior cingulate cortical thickness is a stable predictor of recovery from post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 2013;43(3):645–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001328.

Helpman L, Papini S, Chhetry BT, Shvil E, Rubin M, Sullivan GM, et al. PTSD remission after prolonged exposure treatment is associated with anterior cingulate cortex thinning and volume reduction. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(5):384–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22471.

Levy-Gigi E, Szabo C, Kelemen O, Keri S. Association among clinical response, hippocampal volume, and FKBP5 gene expression in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder receiving cognitive behavioral therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(11):793–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.017.

Rubin M, Shvil E, Papini S, Chhetry BT, Helpman L, Markowitz JC, et al. Greater hippocampal volume is associated with PTSD treatment response. Psychiatry Res. 2016;252:36–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2016.05.001.

King AP, Block SR, Sripada RK, Rauch S, Giardino N, Favorite T, et al. Altered default mode network (DMN) resting state functional connectivity following a mindfulness-based exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in combat veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(4):289–99. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22481.

Lyoo IK, Kim JE, Yoon SJ, Hwang J, Bae S, Kim DJ. The neurobiological role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in recovery from trauma. Longitudinal brain imaging study among survivors of the South Korean subway disaster. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):701–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.70.

Nicholson AA, Densmore M, Frewen PA, Theberge J, Neufeld RW, McKinnon MC, et al. The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: unique resting-state functional connectivity of basolateral and centromedial amygdala complexes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(10):2317–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.79.

Mutschler I, Wieckhorst B, Kowalevski S, Derix J, Wentlandt J, Schulze-Bonhage A, et al. Functional organization of the human anterior insular cortex. Neurosci Lett. 2009;457(2):66–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2009.03.101.

Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, Brand B, Schmahl C, Bremner JD, et al. Emotion modulation in PTSD: clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):640–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081168.

Abdallah CG, Southwick SM, Krystal JH. Neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a path from novel pathophysiology to innovative therapeutics. Neurosci Lett. 2017;649:130–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2017.04.046.

Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, Wig GS, Barnes KA, Church JA, et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron. 2011;72(4):665–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.006.

Nilsen AS, Hilland E, Kogstad N, Heir T, Hauff E, Lien L, et al. Right temporal cortical hypertrophy in resilience to trauma: an MRI study. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016;7:31314. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.31314.

Admon R, Milad MR, Hendler T. A causal model of post-traumatic stress disorder: disentangling predisposed from acquired neural abnormalities. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(7):337–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.05.005.

Robinson BL, Shergill SS. Imaging in posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24(1):29–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283413519.

Bremner JD. Hypotheses and controversies related to effects of stress on the hippocampus: an argument for stress-induced damage to the hippocampus in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Hippocampus. 2001;11(2):75–81; discussion 2-4. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.1023.

Winter H, Irle E. Hippocampal volume in adult burn patients with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2194–200. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2194.

Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Ciszewski A, Kasai K, Lasko NB, Orr SP, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(11):1242–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn958.

Kasai K, Yamasue H, Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Rauch SL, Pitman RK. Evidence for acquired pregenual anterior cingulate gray matter loss from a twin study of combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):550–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.022.

Patriat R, Birn RM, Keding TJ, Herringa RJ. Default-mode network abnormalities in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(4):319–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.01.010.

Herringa RJ. Trauma, PTSD, and the developing brain. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(10):69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0825-3.

Apps R, Strata P. Neuronal circuits for fear and anxiety—the missing link. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(10):642. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn4028.

Meabon JS, Huber BR, Cross DJ, Richards TL, Minoshima S, Pagulayan KF, et al. Repetitive blast exposure in mice and combat veterans causes persistent cerebellar dysfunction. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(321):321ra6. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa9585.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the US Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD, the NIMH, and the Brain and Behavior Foundation for their support. We would also like to thank our colleagues for their thoughtful conversation while preparing this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) National Center for PTSD, NIH [MH-101498]; Brain and Behavior Foundation Young Investigator Award [NARSAD]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsors. The sponsors had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Teddy J. Akiki and Christopher L. Averill declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Chadi G. Abdallah has received grants from the NIH [MH-101498], the Brain and Behavior Foundation Young Investigator Award [NARSAD], and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) National Center for PTSD. Dr. Abdallah has served as a consultant or on advisory boards for Genentech and Janssen. He also serves as editor for the journal Chronic Stress published by SAGE Publications, Inc.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Disaster Psychiatry: Trauma, PTSD, and Related Disorders

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Akiki, T.J., Averill, C.L. & Abdallah, C.G. A Network-Based Neurobiological Model of PTSD: Evidence From Structural and Functional Neuroimaging Studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19, 81 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0840-4

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0840-4