Abstract

Purpose of Review

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a neurodegenerative disease that can be clinically and pathologically similar to Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Current understanding of DLB genetics is insufficient and has been limited by sample size and difficulty in diagnosis. The first genome-wide association study (GWAS) in DLB was performed in 2017; a time at which the post-GWAS era has been reached in many diseases.

Recent Findings

DLB shares risk loci with AD, in the APOE E4 allele, and with PD, in variation at GBA and SNCA. Interestingly, the GWAS suggested that DLB may also have genetic risk factors that are distinct from those in AD and PD.

Summary

Although off to a slow start, recent studies have reinvigorated the field of DLB genetics and these results enable us to start to have a more complete understanding of the genetic architecture of this disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a neurodegenerative disease that shares clinical, pathological and genetic features with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Lewy body dementia is a term that encompasses both DLB and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD), and the ‘one year rule’ is used to assess the temporal onset of dementia versus parkinsonism, in order to differentiate the two diseases. If parkinsonism occurs at the same time or within 1 year of dementia, a diagnosis of DLB is made, whereas if parkinsonism precedes the onset of dementia by a year or more, PDD is diagnosed. The fundamental feature of DLB is dementia, which often occurs with parkinsonism, early fluctuations in cognition and attention, visual hallucinations and REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD) [1••, 2]. Autonomic dysfunction, sleep irregularities, depression and anxiety are also common. DLB is a devastating disease because of its symptoms, as well as the fact that there is currently no cure or disease modifying therapy available. Furthermore, DLB is thought to have a shorter disease duration [3] and decreased survival rate compared to AD [4]. The need to understand the disease pathobiology is imperative for the development of disease-specific therapies.

It is now clear that DLB has a strong genetic component. Although most cases are sporadic, a number of reports have demonstrated the occurrence of the disorder in families [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], in addition to the identification of genetic loci that modulate risk for the development of DLB [14, 15, 16••]. As such, using common genetic variants, the proportion of the phenotype that can be attributed to genetic factors was estimated to be 36% [16••].

DLB Genetics Has Remained Largely Elusive

Despite the fact that we now know that genetics plays a role in the disease, genes that cause DLB are still to be identified. In comparison with AD and PD, we know far less about the genetic basis of DLB. There are multiple reasons for this. Firstly, DLB is difficult to diagnose, as phenotypic overlaps with other neurodegenerative diseases can diminish chances of an accurate diagnosis. The lines between different neurodegenerative diseases can often be blurred, and a patient may show features of one or several other diseases, both ante and post mortem. Additionally, DLB is not as frequently recognized as a disease compared to other well-known disorders, such as AD. Both factors result in a substantial rate of mis- and under-diagnosis. This has hindered the collection of large cohorts of cases whose diagnosis is certain, and as a consequence, has limited large-scale genetic analyses. Furthermore, as the disease is age-related, and typically occurs in those aged 65 or older, the likelihood of gathering biomaterials from multiple family members for genetic testing of familial DLB is small. This, coupled with the fact that families with DLB are rare, has limited the understanding of Mendelian DLB genetics. Although still a prevalent cause of disease in the elderly, DLB is less common than diseases such as AD and PD, and hence cohorts will generally be smaller for this disease.

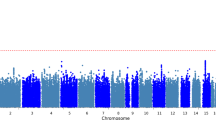

Moreover, some previous genetic studies have focused on Lewy body disease (PD, DLB and PDD) as a whole, and not specifically to genetic alterations that are unique to DLB (Table 1). Ultimately, there is less research conducted in DLB compared to AD and PD (Fig. 1a). DLB was only described as a separate disease entity in 1984, comparatively later than AD or PD (Fig. 1b). Thus, genetic research in DLB is only just gathering momentum; for example, the first genome-wide association study (GWAS) in DLB was conducted in 2017 [16••], at a time when we have reached the post-GWAS era in many diseases. Genetic studies have already shown that DLB shares genetic risk factors with AD and PD; however, recent findings suggest that DLB may also have a unique genetic architecture [16••].

Number of publications and important landmarks in Dementia with Lewy bodies. a Number of research publications in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies from 1995 to 2017. Research publications are far fewer in dementia with Lewy bodies as compared to Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s diseases. The terms ‘Alzheimer’s disease’, ‘Parkinson’s disease’ and ‘Dementia with Lewy bodies’ were used as input for PubMed and the resulting number of publications per year were plotted. The time points begin in 1995, when DLB was first established as a disease entity. b Timeline of important landmarks in dementia with Lewy bodies. Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease were proposed as disease entities many years before the establishment of DLB as a disease (1817, 1906 versus 1976); however, cortical Lewy bodies were identified in 1960. The first diagnostic criteria for DLB were established in 1996, and updated in 2005 and 2017. This timeline has been created using the historical landmarks for DLB from Kenji Kosaka’s chapter (chapter 1), in his recent book [33]. PD = Parkinson’s disease, AD = Alzheimer’s disease, DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies

Well-established Genetic Findings in DLB: APOE, SNCA and GBA

In order to adequately implicate a gene in disease, detailed assessment of the gene in question is required, with a view to reproduce findings in independent studies. Replication studies are fundamental to distinguish true associations from false positive findings, and thus in the validation of the results of the initial study [34]. To date, only three genes have been convincingly established to be involved in DLB: APOE, GBA and SNCA. Variation in the SNCA gene can modulate risk for or cause DLB phenotypes. The established risk factors for DLB are also known to impart risk to either AD (APOE) or PD (GBA, SNCA). Of note, AD and PD do not share common genetic risk factors between them [35]. This is in accordance with a recent study, which showed no evidence of correlation between PD and AD, but showed that the genetic correlation between DLB and AD was 0.578 (SE ± 0.075), and between DLB and PD was 0.362 (SE ± 0.107). The APOE locus is highly associated with AD and DLB. When removing this locus from the analysis, the correlation between AD and DLB was reduced to 0.332, which does not differ significantly from the correlation between DLB and PD [36]. It should be noted that this study used a genotyping array enriched for neurological disease variants and so was not entirely unbiased.

SNCA

The SNCA gene was first implicated in DLB when point mutations, p.Ala53Thr and p.Glu46Lys, and locus multiplications were identified in families with mixed phenotypes of parkinsonism and dementia that resembled DLB [37,38,39]. Locus multiplications resulting in three copies (heterozygous duplication) or four copies (homozygous duplication or heterozygous triplication) of SNCA have been described in PD, PDD and DLB [39,40,41,42,43,44], and a comprehensive review of SNCA mutations in parkinsonism was conducted by Rosborough and colleagues [45]. Pathogenic mutations in SNCA are very rare, can result in a wide phenotypic spectrum from PD, PDD, DLB, multiple system atrophy (MSA) and even frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [46,47,48,49], and can show heterogeneity between members of the same family in terms of age of onset, phenotype and pathology. Furthermore, not all duplications are fully penetrant [41]. SNCA disease-causing point mutations fall in the amphipathic region of alpha-synuclein; however, their role in disease is not clear, as not all mutations have the same effect. It has been hypothesized that these mutations may perturb membrane binding activity, or initiate disease by increasing the propensity of the protein to aggregate. Triplications result in overexpression of SNCA mRNA and protein [50], causing a more severe phenotype and earlier disease onset.

In addition to causing disease, SNCA has also been shown to modulate disease risk for DLB and PD. Interestingly, PD and DLB show differential association profiles at the SNCA locus, a phenomenon first reported in a study analysing AD and PD-associated loci in DLB [28]. This difference was also observed in the recent DLB GWAS (which had some overlap of samples included in the previous study) [16••]. In detail, the most associated single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at the SNCA locus in a meta-analysis of GWA studies in Parkinson’s disease is found 3′ to the gene (rs356182) [51]; this SNP was not significant in the DLB GWAS, where instead, association at the SNCA locus is mediated by a SNP 5′ of the gene (rs7681440). Guella and colleagues also found in a study of DLB, PD, PDD and healthy controls that the risk for dementia was associated with a locus located 5′ of the gene, and the risk for parkinsonism was associated with variants located 3′ to the gene [31]. Using GTEx data, it was shown that the rs7681440 SNP is an eQTL for RP11-67M1.1, an antisense gene and a negative regulator of SNCA expression. The alternative allele mediates an increase in SNCA expression in the cerebellum through decreasing expression of the SNCA repressor [16••], which would fit with a mechanism of increased SNCA expression increasing risk for disease, although further studies are required to confirm this hypothesis.

Interestingly, the most significantly associated SNP in SNCA in DLB was shown to be in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with a SNP in PD that was significantly associated with the disease once the most significant SNP was removed [51].

SNCA methylation was suggested to be significantly decreased in DLB [52], albeit in a small study of 20 clinical DLB cases and 20 controls. Differential expression of SNCA isoforms in DLB have been proposed [52, 53], but requires further study due to small sample sizes. A systematic review concluded that DLB patients have decreased alpha-synuclein in CSF and this may be used to differentiate these patients from AD, but not PD cases [54].

REP1 is a polymorphic microsatellite repeat upstream of the SNCA translation start site. Variations in REP1 length have been associated with PD [55], and PD-associated REP1 polymorphisms enhance SNCA transcription in transgenic mice [56]. It was later shown that a SNP in SNCA identified to be associated with PD in a GWAS (rs3857059) is in LD with the REP1 risk allele (D′ = 0.872, R2 = 0.365) [57]; however, in a separate, albeit small study, REP1 was not associated with PD [31]. So far, it is not known whether REP1 polymorphisms are involved in DLB, given that this has not been tested specifically.

The SNCA gene is highly relevant to synucleinopathies as its encoded protein, alpha-synuclein, aggregates within neurons to form Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites [58], which are the pathological hallmark of PD, PDD and DLB. The anatomical distribution of Lewy-related pathology is often widespread to limbic and neocortical areas in DLB and PDD, and at end stage, the diseases are indistinguishable. The presynaptic aggregation of alpha-synuclein is thought to cause neurodegeneration in DLB [59], where it has been shown to be phosphorylated [60]. Alpha-synuclein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases not only differs in the brain regions affected, but also the cell types in which it is found, for example, the aggregation of alpha-synuclein in glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCI) is typically seen in multiple system atrophy (MSA). A recent study demonstrated that the alpha-synuclein species in GCIs and LBs are conformationally and biologically distinct [61•]. Lewy-related pathology can also been seen as a secondary pathology in Alzheimer’s disease [62], predominantly in the amygdala [63].

APOE

Genetic variation at two SNPs (rs429358 and rs7412) in the APOE gene result in three alleles, of which the ε4 allele is well established to increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease in a dose-dependent manner [64, 65]. APOE ε4 allele dosage has also been shown to be a risk factor for the development of DLB, and whilst first identified over 20 years ago [14], has since been replicated in a number of studies [3, 16••, 27,28,29,30, 66].The protective effect of the ε2 allele is less well established in DLB, conferring protection in some studies [67] but not others [3]. DLB patients who carry ε4 alleles die at a younger age than those who do not [30]. It was hypothesized that the association of APOE ε4 in DLB may be driven by the presence of AD-related neuropathology [68], which can often be seen alongside Lewy-related pathology in DLB brains. However, the association with APOE ε4 remains robust in ‘pure’ DLB cases who have Lewy bodies but minimal or low-level Alzheimer-related pathology [66], perhaps suggesting that APOE is correlated to dementia in a mechanism unrelated to the amyloid cascade. Interestingly, APOE is not a risk factor for PD [69], which demonstrates its specificity for dementia risk. Furthermore, a recent study showed that APOE ε4 dose was associated with decreased hippocampal volumes irrespective of AD or DLB diagnosis [70].

APOE encodes apolipoprotein E, a protein that is involved in lipid binding, transport and receptor-mediated endocytosis [71] and that is suggested to influence AD pathogenesis through mechanisms related to amyloid beta (Aβ) aggregation and clearance. However, other possible pathological processes involving tau phosphorylation, neuroplasticity and neuroinflammation have been proposed [72].

APOE alleles differ in CpG content and in ε3/ε4 genotype carriers, APOE CpG island methylation was significantly decreased in the frontal lobe of AD and DLB patients, with the most significant decrease in DLB patients with mixed AD and LB pathology, as compared to pure AD or LB pathology cases [73]. Although further studies are required to replicate this finding, and to analyse differential methylation of other APOE genotypes in DLB, this may suggest that epigenetic changes at this locus play a role in disease etiology.

GBA

Homozygous mutations in the GBA gene cause Gaucher disease (GD); through astute clinical observation, it was noted that some GD patients showed parkinsonian features [74], and that heterozygous carriers of these variants had a higher prevalence of PD [75], leading to the discovery that heterozygous variants in GBA can predispose to PD, with an odds ratio (OR) of 5.43 (95% CI, 3.89–7.57) [76]. This was also shown to be true for DLB [15, 16••, 27, 30, 77,77,78,79,80,81,83], with an OR of 8.28 (95% CI, 4.78–14.88), where GBA variants are linked to earlier disease onset and death [15].

PD patients with GBA variants have an approximate 2.4-fold increased incidence of cognitive impairment [84] and, given the increased OR for DLB, suggests a strong affinity of GBA variants for Lewy body dementia. Whilst a role for variants in GBA in DLB disease risk modulation has been unequivocally established, the role of specific variants in DLB pathogenesis is less clear, due to disparities between studies in classification of GBA variants (analysis restricted to GD variants or also including other rare variants), and differential coverage of the gene (genotyping or whole gene sequencing). Furthermore, some studies do not analyse the p.Glu365Lys variant, as it does not cause GD when homozygous and only reduces enzyme activity by approximately half [85]. Nevertheless, p.Glu365Lys is associated with PD, and is thought to explain the genome-wide signal at the SYT11-GBA locus [86]. This may also be the case for DLB, as the strongest association at the GBA locus was in strong LD with p.Glu365Lys (D′ = 0.9, R2 = 0.78).

Mutations in GBA reduce activity of its lysosomal enzyme, β-glucocerebrosidase (Gcase), and Gcase activity has been shown to be reduced in sporadic PD brains without GBA mutations, due to decreased amount of protein [87]. Interestingly, Gcase deficiency can be detected in the CSF of PD patients, irrespective of mutation carrier status [88], providing promise for use as a biomarker in PD. It is hypothesized that decreased Gcase activity leads to impaired degradation of alpha-synuclein within the lysosome, resulting in its accumulation. In turn, increased alpha-synuclein perturbs Gcase transport to lysosome, therefore furthering lysosomal dysfunction [89]. Thus far, most studies have analysed Gcase deficiency in PD, and it is not known whether the same occurs in DLB. Nevertheless, Gcase was also significantly reduced in DLB CSF in a small study comparing DLB, AD, FTD and controls [90], suggesting its potential use as a biomarker for disease.

GWAS

The first DLB GWAS was conducted in late 2017, and incorporated a total of 1743 DLB patients (1324 of which had autopsy supported diagnosis) and 4454 controls [16••]. Genotyping data was enriched with SNPs imputed from the haplotype reference consortium, to allow detection of lower frequency variants. SNCA, GBA and APOE loci were significantly associated with DLB in the discovery and replication phases, as well as the meta-analysis of both stages. In the discovery phase, two other loci were genome-wide significant: BCL7C/STX1B (OR 0.74, 0.67–0.82; p = 3.30 × 10−9) and GABRB3 (OR 1.34, 1.21–1.48; p = 2.62 × 10−8). However, the GABRB3 signal did not maintain significant association when restricting analysis to pathologically diagnosed samples (p = 1.21 × 10−7). Loci with p < 5 × 10−6 were genotyped in the replication phase, and CNTN1, a locus that reached suggestive association in the discovery phase (OR 1.58, 1.32–1.88; p = 4.32 × 10−7, pathologically diagnosed cases only), was significantly associated in the replication phase (p < 0.05). As CNTN1 lies < 500,000 bp away from the LRRK2 locus, samples that harboured the p.Gly2019Ser LRRK2 variant were removed from analysis, without significant effect on the association at CNTN1. However, whether other LRRK2 variants may mediate the association cannot be ruled out. BCL7C/STX1B was genome-wide significant in the meta-analysis; however, this was mainly driven by the discovery phase, and requires further replication. Despite the identification of interesting candidates, replication of novel associations is required, and further GWA studies with larger cohorts are warranted. Heritability was shown to be higher than expected given chromosome size on chromosomes 19, 5, 6, 7 and 13 but apart from chromosome 19, no genome-wide significant variants were identified, suggesting that, perhaps, other DLB genes may be present on these chromosomes.

Studies in Familial Forms of DLB

Although not particularly common, several DLB families have been studied, but these have failed to shed much light on the genetics of the disease. Only a small proportion of patients within these families underwent genetic analysis, and if performed, it was usually minimal with very few cases assessed at the exome or genome levels. As mentioned above, variation in SNCA sequence or dosage has been identified in families as the cause of mixed PD and DLB phenotypes. Some DLB patients have a family history of neurodegenerative disease, but not necessarily of DLB, with family members being diagnosed with AD or PD. Alzheimer families with mutations in APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 have been described with phenotypes of mixed parkinsonism and dementia suggestive of DLB [91,91,93], and extensive Lewy body pathology has also been found in Alzheimer’s families with these mutations [94, 95], suggestive of a possible mechanistic link. Indeed, DLB cases frequently present Aβ pathology at autopsy [96], and it has been suggested that Aβ accumulation can trigger Lewy body disease [97]. A recent review by Vergouw and colleagues [98] provides a summary of familial studies in DLB. The most promising study to identify a novel DLB gene relied on linkage analysis in a DLB family which identified a locus on chromosome 2q35-q36 [11]; however, no gene was subsequently identified [99]. This could be because the variant was not detectable with current technology or, perhaps, the linkage results were misleading.

As our knowledge of the disease progresses, the diagnostic criteria for DLB are updated (Fig. 1b) to provide increasing sensitivity and specificity for accurate diagnoses [1••]. It is also worth considering whether previous reports in DLB families, which occurred when the first consensus criteria were in use, have patients that would meet current diagnostic criteria for DLB. The lack of autopsy data in some of these studies makes a reliable diagnosis difficult. Moving forward, genetic analysis of multiple family members with well characterized clinical and autopsy data that meet more recent diagnostic criteria for DLB, will be paramount in identifying novel disease-causing genes.

Genes Causative of Other Neurodegenerative Diseases

As DLB may clinically and pathologically resemble Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s diseases, speculation as to whether AD- or PD-causing genes may also be involved in the pathogenesis of DLB prompted the study of these genes in small cohorts of mainly sporadic DLB cases. However, due to the phenotypic similarities between diseases, it is still unclear whether the mutations identified play a role in DLB or simply occur in misdiagnosed cases. This issue is complicated further by the heterogeneity of phenotype that can be associated with some of these mutations [41, 46,47,48, 91, 93, 100].

Mutations that are established to be pathogenic in APP and PSEN1 were found in either a clinical DLB case [29]; or in pathologically confirmed DLB cases, of which 69% of the cohort also met pathological criteria for Alzheimer’s disease [27]. Furthermore, studies of genes that cause other neurodegenerative diseases have identified variants in DLB patients that have been previously reported, but are of unknown pathogenic consequence in genes such as CHMP2B, SQSTM1, PSEN2 [30] and GRN [29]. Novel variants in MAPT [29] and multiple variants of uncertain significance have also been reported. A compound heterozygous mutation in PARK2 was identified in a DLB patient [30]; however it is unclear whether the data was phased. Rare variants in GRN were hypothesized to be associated with DLB, albeit in a very small study of 58 DLB cases and 380 controls [32]. Nevertheless, if the reported mutation carriers do in fact have DLB, mutations in genes known to cause Mendelian forms of other neurodegenerative diseases only occur in a small proportion of DLB cases.

Other Findings

The MAPT H1G sub-haplotype was associated with clinical DLB; however, the association was attenuated when pathologically diagnosed samples were included in analysis [24], weakening evidence for a role specific to DLB. The H1 haplotype may be associated with more severe alpha-synuclein deposition, as suggested in a small study of 22 DLB brains [101]. MAPT p.Ala152Thr has been proposed to be associated with DLB in a clinical DLB cohort [25]. This variant is also associated with AD and FTD-spectrum disorders [102], but not PD [25, 102]. However, the MAPT locus showed no evidence of association in the DLB GWAS [16••], and this is of interest as the MAPT locus is a highly significant result in PD, reaching genome-wide significance even in smaller studies of approximately the same number of cases as the DLB GWAS [103]. Therefore, there is limited convincing evidence for a role of MAPT variation in DLB, and further studies of risk associated haplotypes in larger cohorts are needed.

Variants in the TREM2 gene confer a risk for the development of AD similar to that associated to one ε4 allele of APOE, an association mediated primarily by the p.Arg47His variant, but also by others, such as p.Arg62His. The p.Arg47His variant was not found to be associated with DLB [16••, 22]; however, in a small study of 58 DLB cases, p.Arg62His was nominally associated with DLB (uncorrected p value = 0.0024, OR = 3.2 [95% CI 1.7–27] [32], although this would not survive multiple-test correction. Again, further study is required to identify the role, if any, of TREM2 in DLB.

Pathogenic hexanucleotide repeat expansions in the C9ORF72 gene are the most common cause of FTD and/or ALS. Analysis of the expansion in neuropathologically diagnosed DLB patients found three cases with either 32 or 33 repeats, in a combined total of 1562 patients [17, 19, 104]; whereas studies of clinically diagnosed DLB patients have identified two patients with > 30 repeats [18, 19, 105]. This suggests that repeat expansions in C9ORF72 are not a common cause of DLB.

An increased frequency of the LRRK2 p.Gly2019Ser variant was seen in DLB compared to controls (0.0021 versus 0.0003, respectively) [16••]; however, this was not statistically assessed given its low frequency. This variant has previously been seen in a clinical DLB case [26], and in two Ashkenazi Jewish individuals with DLB [80], demonstrating a low frequency in this disease. Where studied, no other pathogenic LRRK2 mutations were found in DLB cases [27, 29, 30], and no LRRK2 variants were significantly associated with DLB [26]. Whilst LRRK2 genetic variation does not seem to occur often in DLB, it is difficult to distinguish between PD, PDD and DLB and thus assess the contribution of LRRK2 specifically to DLB [106]. LRRK2 mutation carriers in PD have a lower rate of dementia [107], perhaps providing further evidence against a role in DLB.

The apparent lack of association for other strong AD and PD risk loci, such as TREM2, MAPT, CLU, PICALM, and BIN1 may hint at distinct genetic features for DLB, or may be attributed to insufficient power to detect associations.

Requirements for Future DLB Genetic Studies

Genetic research in DLB is only just beginning to come together, providing hope for future characterization of the genetic architecture of the disease. In order to identify additional genes implicated in DLB, it will be imperative to study more individuals with the disease. This will require collaborative approaches in order to increase cohort numbers and more studies that are focused on replicating results. As well as generating genetic data, it is important to collect detailed clinical and pathological data on patients studied.

There is a clear need for more unbiased genetic studies (genome- or exome-wide). The majority of genetic studies in DLB thus far have been hypothesis based, largely trying to identify candidate genes (Table 1). Table 1 also highlights the fact that some DLB samples have been used in multiple genetic studies, an event that should be made clear and that can severely bias results, certainly for a disease where sample collections are small.

Large-scale genetics studies in neurodegenerative diseases have been dominated by European and American cohorts. The study of patients from other populations could allow the discovery of population-specific, predisposing variants, which in turn may provide novel insights into the biological processes that occur in disease. DLB research in Japan has been invaluable for furthering our understanding of the disease. For instance, the earliest identification of DLB patients [108], and the study of [(123)I]MIBG myocardial scintigraphy to distinguish DLB [109], were first proposed by Japanese scientists. Detailed, large-scale genetic analyses of these patients could be transformative for the field.

Conclusion

Understanding the genetic bases of a disease can allow us to identify pathways and mechanisms involved in the disease pathobiology. An example of this is in AD, where the identification of APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 mutations were crucial for the development of the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Furthermore, genetics may be able to help us tease apart PD, AD, DLB and PDD using molecular data. As diagnostic criteria [1••] and understanding of the disease improves [110,110,112], we will be able to have a better understanding of the biological processes underlying DLB, and this may lead to the identification of disease-specific therapeutic targets.

Next-generation sequencing technology has revolutionized genetic analysis, and in combination with large-scale databases of genetic variation such as gnomAD or ExAC [113], has allowed us to have a better understanding of genetic variation in humans. This knowledge is going to improve as datasets increase—the 1000 Genomes Project, which began in 2008, included whole genome data from 2504 individuals [114], yet current databases such as ExAC and gnomAD [113], now provide data from 60,706 exomes or 123,136 exomes and 15,496 genomes, respectively. Although these types of datasets will include information from individuals who will suffer from neurodegenerative disease, they have been invaluable in informing the evaluation of potentially pathogenic variants [115]. Furthermore, improved interpretation of GWAS results will enable genetic variants to be linked to a functional role in disease risk [116]. In addition, polygenic risk scores can be used to calculate an individual’s lifetime risk for disease based on their genetic profile, a process that has already been implemented in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases [117, 118], and that may allow for identification of presymptomatic individuals.

The role for genetics in human biology is multifaceted and complex, and thus we need to integrate DNA sequencing, with RNA and protein expression, tissue and cell-specific expression and epigenetic analyses in order to reveal as complete a picture as possible. The overall objective is to understand the pathways that are perturbed in disease and that should be therapeutically targeted. Therapies will likely need to be administered prior to clinical disease onset, and therefore must target the prodrome. Genetic studies may allow us to identify those particularly susceptible for the development of the disorder, by utilizing polygenic risk scores or causative mutations.

Moreover, genetics has informed the use of biomarker: by associating genes with disease, there is the potential to analyse the proteins encoded by those genes in patients in order to aid diagnosis. For example, it has been suggested that Gcase [90] or alpha-synuclein [54] levels may be altered in the CSF of DLB patients. A recent study identified phosphorylated alpha-synuclein in skin biopsies of DLB patients, which was absent in controls, or those with an alternative diagnosis of dementia [119]. Although requiring replication, phosphorylated alpha-synuclein in skin was suggested to contribute to autonomic dysfunction and may provide an easy and relatively inexpensive biomarker for DLB [120].

Although DLB genetic research is still only in its beginning, interest in this area has increased, resulting in the identification of several genes that are involved in the disease. This is the first step to obtain a complete picture of the genetic architecture of DLB. As we get closer to this stage, we will be able to better understand disease pathogenesis and to nominate candidate disease-specific therapeutic targets, which will enable us to slow, or even halt, this devastating disease.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Halliday G, Taylor J-P, Weintraub D, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89:88–100. The diagnostic criteria for DLB were updated in this manuscript to rely more heavily on biomarkers to aid diagnosis. REM sleep behaviour disorder was made a core feature.

McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–72.

Singleton AB, Wharton A, O’Brien KK, Walker MP, McKeith IG, Ballard CG, et al. Clinical and neuropathological correlates of apolipoprotein E genotype in dementia with Lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;14:167–75.

Price A, Farooq R, Yuan J-M, Menon VB, Cardinal RN, O’Brien JT. Mortality in dementia with Lewy bodies compared with Alzheimer’s dementia: a retrospective naturalistic cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017504.

Tsuang DW, DiGiacomo L, Bird TD. Familial occurrence of dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:179–88.

Ohara K, Takauchi S, Kokai M, Morimura Y, Nakajima T, Morita Y. Familial dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Clin Neuropathol. 1999;18:232–9.

Galvin JE, Lee SL, Perry A, Havlioglu N, McKeel DW Jr, Morris JC. Familial dementia with Lewy bodies: clinicopathologic analysis of two kindreds. Neurology. 2002;59:1079–82.

Nervi A, Reitz C, Tang M-X, Santana V, Piriz A, Reyes D, et al. Familial aggregation of dementia with Lewy bodies. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:90–3.

Clarimón J, Molina-Porcel L, Gómez-Isla T, Blesa R, Guardia-Laguarta C, González-Neira A, et al. Early-onset familial Lewy body dementia with extensive tauopathy: a clinical, genetic, and neuropathological study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:73–82.

Bonner LT, Tsuang DW, Cherrier MM, Eugenio CJ, Du Jennifer Q, Steinbart EJ, et al. Familial dementia with Lewy bodies with an atypical clinical presentation. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16:59–64.

Bogaerts V, Engelborghs S, Kumar-Singh S, Goossens D, Pickut B, van der Zee J, et al. A novel locus for dementia with Lewy bodies: a clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorder. Brain. 2007;130:2277–91.

Denson MA, Wszolek ZK, Pfeiffer RF, Wszolek EK, Paschall TM, McComb RD. Familial parkinsonism, dementia, and Lewy body disease: study of family G. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:638–43.

Ishikawa A, Takahashi H, Tanaka H, Hayashi T, Tsuji S. Clinical features of familial diffuse Lewy body disease. Eur Neurol. 1997;38(Suppl 1):34–8.

Hardy J, Crook R, Prihar G, Roberts G, Raghavan R, Perry R. Senile dementia of the Lewy body type has an apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele frequency intermediate between controls and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 1994;182:1–2.

Nalls MA, Duran R, Lopez G, Kurzawa-Akanbi M, McKeith IG, Chinnery PF, et al. A multicenter study of glucocerebrosidase mutations in dementia with Lewy bodies. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:727–35.

•• Guerreiro R, Ross OA, Kun-Rodrigues C, Hernandez DG, Orme T, Eicher JD, et al. Investigating the genetic architecture of dementia with Lewy bodies: a two-stage genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:64–74. This paper describes the first genome-wide association study in DLB and provides evidence for novel loci involved in disease.

Geiger JT, Arthur KC, Dawson TM, Rosenthal LS, Pantelyat A, Albert M, et al. C9orf72 Hexanucleotide repeat analysis in cases with pathologically confirmed dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurodegener Dis. 2016;16:370–2.

Snowden JS, Rollinson S, Lafon C, Harris J, Thompson J, Richardson AM, et al. Psychosis, C9ORF72 and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:1031–2.

Kun-Rodrigues C, Ross OA, Orme T, Shepherd C, Parkkinen L, Darwent L, et al. Analysis of C9orf72 repeat expansions in a large international cohort of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;49:214.e13–5.

Blauwendraat C, Nalls MA, Federoff M, Pletnikova O, Ding J, Letson C, et al. ADORA1 mutations are not a common cause of Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Mov Disord. 2017;32:298–9.

Lorenzo-Betancor O, Ogaki K, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Labbe C, Walton RL, Strongosky AJ, et al. DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser mutation screening in Parkinson’s disease and pathologically confirmed Lewy body disease patients. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22:1323–5.

Walton RL, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Murray ME, Lorenzo-Betancor O, Ogaki K, Heckman MG, et al. TREM2 p.R47H substitution is not associated with dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurol Genet. 2016;2:e85.

Hodges K, Brewer SS, Labbé C, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Walton RL, Strongosky AJ, et al. RAB39B gene mutations are not a common cause of Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;45:107–8.

Labbé C, Heckman MG, Lorenzo-Betancor O, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Walton RL, Murray ME, et al. MAPT haplotype H1G is associated with increased risk of dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:1297–304.

Labbé C, Ogaki K, Lorenzo-Betancor O, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Walton RL, Rayaprolu S, et al. Role for the microtubule-associated protein tau variant p.A152T in risk of α-synucleinopathies. Neurology. 2015;85:1680–6.

Heckman MG, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Contreras MYS, Murray ME, Pedraza O, Diehl NN, et al. LRRK2 variation and dementia with Lewy bodies. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;31:98–103.

Geiger JT, Ding J, Crain B, Pletnikova O, Letson C, Dawson TM, et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals substantial genetic contribution to dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;94:55–62.

Bras J, Guerreiro R, Darwent L, Parkkinen L, Ansorge O, Escott-Price V, et al. Genetic analysis implicates APOE, SNCA and suggests lysosomal dysfunction in the etiology of dementia with Lewy bodies. Hum Mol Genet Oxford Univ Press. 2014;23:6139–46.

Meeus B, Verstraeten A, Crosiers D, Engelborghs S, Van den Broeck M, Mattheijssens M, et al. DLB and PDD: a role for mutations in dementia and Parkinson disease genes? Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:629.e5–629.e18.

Keogh MJ, Kurzawa-Akanbi M, Griffin H, Douroudis K, Ayers KL, Hussein RI, et al. Exome sequencing in dementia with Lewy bodies. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e728.

Guella I, Evans DM, Szu-Tu C, Nosova E, Bortnick SF, Group SCS, et al. α-synuclein genetic variability: a biomarker for dementia in Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. Wiley Online Library. 2016;79:991–9.

Keogh MJ, Wei W, Wilson I, Coxhead J, Ryan S, Rollinson S, et al. Genetic compendium of 1511 human brains available through the UK Medical Research Council Brain Banks Network Resource. Genome Res. 2017;27:165–73.

Kosaka K (2017) Dementia with Lewy bodies: clinical and biological aspects. Springer

NCI-NHGRI Working Group on Replication in Association Studies, Chanock SJ, Manolio T, Boehnke M, Boerwinkle E, Hunter DJ, et al. Replicating genotype-phenotype associations. Nature. 2007;447:655–60.

Moskvina V, Harold D, Russo G, Vedernikov A, Sharma M, Saad M, et al. Analysis of genome-wide association studies of Alzheimer disease and of Parkinson disease to determine if these 2 diseases share a common genetic risk. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1268–76.

Guerreiro R, Escott-Price V, Darwent L, Parkkinen L, Ansorge O, Hernandez DG, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic correlation in dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;38:214.e7–214.e10.

Zarranz JJ, Alegre J, Gómez-Esteban JC, Lezcano E, Ros R, Ampuero I, et al. The new mutation, E46K, of alpha-synuclein causes Parkinson and Lewy body dementia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:164–73.

Morfis L, Cordato DJ. Dementia with Lewy bodies in an elderly Greek male due to α-synuclein gene mutation. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:942–4.

Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, et al. Alpha-synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2003;302:841.

Obi T, Nishioka K, Ross OA, Terada T, Yamazaki K, Sugiura A, et al. Clinicopathologic study of a SNCA gene duplication patient with Parkinson disease and dementia. Neurology. 2008;70:238–41.

Nishioka K, Hayashi S, Farrer MJ, Singleton AB, Yoshino H, Imai H, et al. Clinical heterogeneity of alpha-synuclein gene duplication in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:298–309.

Chartier-Harlin M-C, Kachergus J, Roumier C, Mouroux V, Douay X, Lincoln S, et al. Alpha-synuclein locus duplication as a cause of familial Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2004;364:1167–9.

Ikeuchi T, Kakita A, Shiga A, Kasuga K, Kaneko H, Tan C-F, et al. Patients homozygous and heterozygous for SNCA duplication in a family with parkinsonism and dementia. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:514–9.

Ibáñez P, Bonnet A-M, Débarges B, Lohmann E, Tison F, Pollak P, et al. Causal relation between alpha-synuclein gene duplication and familial Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2004;364:1169–71.

Rosborough K, Patel N, Kalia LV. α-Synuclein and Parkinsonism: updates and future perspectives. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17:31.

Markopoulou K, Dickson DW, McComb RD, Wszolek ZK, Katechalidou L, Avery L, et al. Clinical, neuropathological and genotypic variability in SNCA A53T familial Parkinson’s disease. Variability in familial Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:25–35.

Pasanen P, Myllykangas L, Siitonen M, Raunio A, Kaakkola S, Lyytinen J, et al. Novel α-synuclein mutation A53E associated with atypical multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease-type pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:2180.e1–5.

Kiely AP, Asi YT, Kara E, Limousin P, Ling H, Lewis P, et al. α-Synucleinopathy associated with G51D SNCA mutation: a link between Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy? Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:753–69.

Bougea A, Koros C, Stamelou M, Simitsi A, Papagiannakis N, Antonelou R, et al. Frontotemporal dementia as the presenting phenotype of p.A53T mutation carriers in the alpha-synuclein gene. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;35:82–7

Miller DW, Hague SM, Clarimon J, Baptista M, Gwinn-Hardy K, Cookson MR, et al. Alpha-synuclein in blood and brain from familial Parkinson disease with SNCA locus triplication. Neurology. 2004;62:1835–8.

Nalls MA, Pankratz N, Lill CM, Do CB, Hernandez DG, Saad M, et al. Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:989–93.

Funahashi Y, Yoshino Y, Yamazaki K, Mori Y, Mori T, Ozaki Y, et al. DNA methylation changes at SNCA intron 1 in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;71:28–35.

Beyer K, Lao JI, Carrato C, Mate JL, López D, Ferrer I, et al. Differential expression of alpha-synuclein isoforms in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2004;30:601–7.

Lim X, Yeo JM, Green A, Pal S. The diagnostic utility of cerebrospinal fluid alpha-synuclein analysis in dementia with Lewy bodies—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19:851–8.

Maraganore DM, de Andrade M, Elbaz A, Farrer MJ, Ioannidis JP, Krüger R, et al. Collaborative analysis of alpha-synuclein gene promoter variability and Parkinson disease. JAMA. 2006;296:661–70.

Cronin KD, Ge D, Manninger P, Linnertz C, Rossoshek A, Orrison BM, et al. Expansion of the Parkinson disease-associated SNCA-Rep1 allele upregulates human alpha-synuclein in transgenic mouse brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3274–85.

Simón-Sánchez J, Schulte C, Bras JM, Sharma M, Gibbs JR, Berg D, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–12.

Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–40.

Kramer ML, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ. Presynaptic alpha-synuclein aggregates, not Lewy bodies, cause neurodegeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1405–10.

Colom-Cadena M, Pegueroles J, Herrmann AG, Henstridge CM, Muñoz L, Querol-Vilaseca M, et al. Synaptic phosphorylated α-synuclein in dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain. 2017;140:3204–14.

• Peng C, Gathagan RJ, Covell DJ, Medellin C, Stieber A, Robinson JL, et al. Cellular milieu imparts distinct pathological α-synuclein strains in α-synucleinopathies. Nature [Internet]. 2018; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0104-4. The authors report that pathological alpha-synuclein in glial cytoplasmic inclusions and Lewy bodies are distinct.

Kotzbauer PT, Trojanowsk JQ, Lee VM. Lewy body pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;17:225–32.

Lippa CF, Fujiwara H, Mann DM, Giasson B, Baba M, Schmidt ML, et al. Lewy bodies contain altered alpha-synuclein in brains of many familial Alzheimer’s disease patients with mutations in presenilin and amyloid precursor protein genes. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1365–70.

Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Schmechel D, Pericak-Vance M, Enghild J, Salvesen GS, et al. Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1977–81.

Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–3.

Tsuang D, Leverenz JB, Lopez OL, Hamilton RL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA, et al. APOE ϵ4 increases risk for dementia in pure synucleinopathies. JAMA Neurol. American Medical Association. 2013;70:223–8.

Berge G, Sando SB, Rongve A, Aarsland D, White LR. Apolipoprotein E ε2 genotype delays onset of dementia with Lewy bodies in a Norwegian cohort. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:1227–31.

Nielsen AS, Ravid R, Kamphorst W, Jørgensen OS. Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 in an autopsy series of various dementing disorders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:119–25.

Federoff M, Jimenez-Rolando B, Nalls MA, Singleton AB. A large study reveals no association between APOE and Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:389–92.

Saeed U, Mirza SS, MacIntosh BJ, Herrmann N, Keith J, Ramirez J, et al. APOE-ε4 associates with hippocampal volume, learning, and memory across the spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Dement [Internet]. 2018; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.04.005

Carmona S, Kun-Rodrigues C, Brás J, Guerreiro R. Revisiting the genetics of APOE. Sinapse. 2017;17:27–36.

Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2009;63:287–303.

Tulloch J, Leong L, Chen S, Keene CD, Millard SP, Shutes-David A, et al. APOE DNA methylation is altered in Lewy body dementia. Alzheimers Dement [Internet]. 2018; Available from: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.005

Neudorfer O, Giladi N, Elstein D, Abrahamov A, Turezkite T, Aghai E, et al. Occurrence of Parkinson’s syndrome in type I Gaucher disease. QJM. 1996;89:691–4.

Goker-Alpan O, Schiffmann R, LaMarca ME, Nussbaum RL, McInerney-Leo A, Sidransky E. Parkinsonism among Gaucher disease carriers. J Med Genet. 2004;41:937–40.

Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, Aharon-Peretz J, Annesi G, Barbosa ER, et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1651–61.

Goker-Alpan O, Giasson BI, Eblan MJ, Nguyen J, Hurtig HI, Lee VM-Y, et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations are an important risk factor for Lewy body disorders. Neurology. 2006;67:908–10.

Mata IF, Samii A, Schneer SH, Roberts JW, Griffith A, Leis BC, et al. Glucocerebrosidase gene mutations: a risk factor for Lewy body disorders. Arch Neurol Am Med Assoc. 2008;65:379–82.

Clark LN, Kartsaklis LA, Wolf Gilbert R, Dorado B, Ross BM, Kisselev S, et al. Association of glucocerebrosidase mutations with dementia with lewy bodies. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:578–83.

Shiner T, Mirelman A, Gana Weisz M, Bar-Shira A, Ash E, Cialic R, et al. High frequency of GBA gene mutations in dementia with Lewy bodies among Ashkenazi Jews. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:1448–53.

Tsuang D, Leverenz JB, Lopez OL, Hamilton RL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA, et al. GBA mutations increase risk for Lewy body disease with and without Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2012;79:1944–50.

Gámez-Valero A, Prada-Dacasa P, Santos C, Adame-Castillo C, Campdelacreu J, Reñé R, et al. GBA mutations are associated with earlier onset and male sex in dementia with Lewy bodies. Mov Disord. 2016;31:1066–70.

Nishioka K, Ross OA, Vilariño-Güell C, Cobb SA, Kachergus JM, Mann DMA, et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations in diffuse Lewy body disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:55–7.

Creese B, Bell E, Johar I, Francis P, Ballard C, Aarsland D. Glucocerebrosidase mutations and neuropsychiatric phenotypes in Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementias: review and meta-analyses. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2018;177:232–41.

Malini E, Grossi S, Deganuto M, Rosano C, Parini R, Dominisini S, et al. Functional analysis of 11 novel GBA alleles. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:511–6.

Berge-Seidl V, Pihlstrøm L, Maple-Grødem J, Forsgren L, Linder J, Larsen JP, et al. The GBA variant E326K is associated with Parkinson’s disease and explains a genome-wide association signal. Neurosci Lett. 2017;658:48–52.

Gegg ME, Burke D, Heales SJR, Cooper JM, Hardy J, Wood NW, et al. Glucocerebrosidase deficiency in substantia nigra of parkinson disease brains. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:455–63.

Parnetti L, Paciotti S, Eusebi P, Dardis A, Zampieri S, Chiasserini D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid β-glucocerebrosidase activity is reduced in parkinson’s disease patients. Mov Disord. 2017;32:1423–31.

Gegg ME, Schapira AHV. The role of glucocerebrosidase in Parkinson disease pathogenesis. FEBS J [Internet]. 2018; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.14393

Parnetti L, Balducci C, Pierguidi L, De Carlo C, Peducci M, D’Amore C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid β-glucocerebrosidase activity is reduced in dementia with Lewy Bodies. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34:484–6.

Guyant-Marechal I, Berger E, Laquerrière A, Rovelet-Lecrux A, Viennet G, Frebourg T, et al. Intrafamilial diversity of phenotype associated with app duplication. Neurology. 2008;71:1925–6.

Ishikawa A, Piao Y-S, Miyashita A, Kuwano R, Onodera O, Ohtake H, et al. A mutant PSEN1 causes dementia with Lewy bodies and variant Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:429–34.

Piscopo P, Marcon G, Piras MR, Crestini A, Campeggi LM, Deiana E, et al. A novel PSEN2 mutation associated with a peculiar phenotype. Neurology. 2008;70:1549–54.

Leverenz JB, Fishel MA, Peskind ER, Montine TJ, Nochlin D, Steinbart E, et al. Lewy body pathology in familial Alzheimer disease: evidence for disease- and mutation-specific pathologic phenotype. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:370–6.

Rosenberg CK, Pericak-Vance MA, Saunders AM, Gilbert JR, Gaskell PC, Hulette CM. Lewy body and Alzheimer pathology in a family with the amyloid-beta precursor protein APP717 gene mutation. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100:145–52.

Hepp DH, Vergoossen DLE. Huisman E, Lemstra AW, Netherlands Brain Bank, Berendse HW, et al. Distribution and load of amyloid-β pathology in Parkinson disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2016;75:936–45.

Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Veinbergs I, Sagara Y, Mallory M, Hashimoto M, et al. β-Amyloid peptides enhance α-synuclein accumulation and neuronal deficits in a transgenic mouse model linking Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Nat Acad Sci. 2001;98:12245–50.

Vergouw LJM, van Steenoven I, van de Berg WDJ, Teunissen CE, van Swieten JC, Bonifati V, et al. An update on the genetics of dementia with Lewy bodies. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;43:1–8.

Meeus B, Nuytemans K, Crosiers D, Engelborghs S, Peeters K, Mattheijssens M, et al. Comprehensive genetic and mutation analysis of familial dementia with Lewy bodies linked to 2q35-q36. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:197–205.

Kara E, Kiely AP, Proukakis C, Giffin N, Love S, Hehir J, et al. A 6.4 Mb duplication of the α-synuclein locus causing frontotemporal dementia and Parkinsonism: phenotype-genotype correlations. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1162–71.

Colom-Cadena M, Gelpi E, Martí MJ, Charif S, Dols-Icardo O, Blesa R, et al. MAPT H1 haplotype is associated with enhanced α-synuclein deposition in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:936–42.

Coppola G, Chinnathambi S, Lee JJ, Dombroski BA, Baker MC, Soto-Ortolaza AI, et al. Evidence for a role of the rare p.A152T variant in MAPT in increasing the risk for FTD-spectrum and Alzheimer’s diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3500–12.

Edwards TL, Scott WK, Almonte C, Burt A, Powell EH, Beecham GW, et al. Genome-wide association study confirms SNPs in SNCA and the MAPT region as common risk factors for Parkinson disease. Ann Hum Genet. 2010;74:97–109.

Robinson A, Davidson Y, Snowden JS, Mann DMA. C9ORF72 in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:1435–6.

Yeh T-H, Lai S-C, Weng Y-H, Kuo H-C, Wu-Chou Y-H, Huang C-L, et al. Screening for C9orf72 repeat expansions in parkinsonian syndromes. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1311.e3–1311.e34.

Ross OA, Toft M, Whittle AJ, Johnson JL, Papapetropoulos S, Mash DC, et al. Lrrk2 and Lewy body disease. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:388–93.

Srivatsal S, Cholerton B, Leverenz JB, Wszolek ZK, Uitti RJ, Dickson DW, et al. Cognitive profile of LRRK2-related Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30:728–33.

Kosaka K, Yoshimura M, Ikeda K, Budka H. Diffuse type of Lewy body disease: progressive dementia with abundant cortical Lewy bodies and senile changes of varying degree—a new disease? Clin Neuropathol. 1984;3:185–92.

Yoshita M, Taki J, Yamada M. A clinical role for [(123)I]MIBG myocardial scintigraphy in the distinction between dementia of the Alzheimer’s-type and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:583–8.

Slaets S, Van Acker F, Versijpt J, Hauth L, Goeman J, Martin J-J, et al. Diagnostic value of MIBG cardiac scintigraphy for differential dementia diagnosis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30:864–9.

Flanigan PM, Khosravi MA, Leverenz JB, Tousi B. Color vision impairment in dementia with lewy bodies: a novel and highly specific distinguishing feature from Alzheimer dementia. Alzheimers Dement Elsevier. 2017;13:P1460.

Brigo F, Turri G, Tinazzi M. 123I-FP-CIT SPECT in the differential diagnosis between dementia with Lewy bodies and other dementias. J Neurol Sci. 2015;359:161–71.

Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–91.

Birney E, Soranzo N. Human genomics: The end of the start for population sequencing. Nature. 2015;526:52–3.

Blauwendraat C, Kia DA, Pihlstrøm L, Gan-Or Z, Lesage S, Gibbs JR, et al. Insufficient evidence for pathogenicity of SNCA His50Gln (H50Q) in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;64:159.e5–8.

Huang K-L, Marcora E, Pimenova A, Di Narzo A, Kapoor M, Jin SC, et al. A common haplotype lowers SPI1 (PU.1) expression in myeloid cells and delays age at onset for Alzheimer’s disease [Internet]. bioRxiv. 2017 [cited 2018 May 25]. p. 110957. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/02/26/110957

Logue MW, Panizzon MS, Elman JA, Gillespie NA, Hatton SN, Gustavson DE, et al. Use of an Alzheimer’s disease polygenic risk score to identify mild cognitive impairment in adults in their 50s. Mol Psychiatry [Internet]. 2018; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0030-8

Ibanez L, Dube U, Saef B, Budde J, Black K, Medvedeva A, et al. Parkinson disease polygenic risk score is associated with Parkinson disease status and age at onset but not with alpha-synuclein cerebrospinal fluid levels. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:198.

Donadio V, Incensi A, Rizzo G, Capellari S, Pantieri R, Stanzani Maserati M, et al. A new potential biomarker for dementia with Lewy bodies: Skin nerve α-synuclein deposits. Neurology. 2017;89:318–26.

Wood H. Dementia: Skin α-synuclein deposits - a new biomarker for DLB? Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:514.

Acknowledgements

Rita Guerreiro and Jose Bras’ work is funded by fellowships from the Alzheimer’s Society. Tatiana Orme’s work is funded by a scholarship from The Lewy Body Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Tatiana Orme reports grants from the Lewy Body Society. Rita Guerreiro and Jose Bras report grants from the Alzheimer’s Society.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Dementia

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Orme, T., Guerreiro, R. & Bras, J. The Genetics of Dementia with Lewy Bodies: Current Understanding and Future Directions. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 18, 67 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-018-0874-y

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-018-0874-y