Abstract

Purpose of Review

To describe models of integrated and co-located care for opioid use disorder (OUD), hepatitis C (HCV), and HIV.

Recent Findings

The design and scale-up of multidisciplinary care models that engage, retain, and treat individuals with HIV, HCV, and OUD are critical to preventing continued spread of HIV and HCV. We identified 17 models within primary care (N = 3), HIV specialty care (N = 5), opioid treatment programs (N = 6), transitional clinics (N = 2), and community-based harm reduction programs (N = 1), as well as two emerging models.

Summary

Key components of such models are the provision of (1) medication-assisted treatment for OUD, (2) HIV and HCV treatment, (3) HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, and (4) behavioral health services. Research is needed to understand differences in effectiveness between co-located and fully integrated care, combat the deleterious racial and ethnic legacies of the “War on Drugs,” and inform the delivery of psychiatric care. Increased access to harm reduction services is crucial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The opioid epidemic in the USA, especially the rise in injection drug use (IDU), has ushered in a volatile and evolving risk environment for HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) [1,2,3,4,5], particularly in rural areas [2, 6]. In 2016, over 2 million Americans had an opioid use disorder (OUD), with 11.5 million people aged 12 years or older misusing prescription painkillers and 948,000 using heroin and/or synthetic opioids such as fentanyl [7]. Currently, 10–20% of people who misuse prescription opioids escalate to injection [8, 9], contributing to substantial risk for new HIV and HCV outbreaks due to the sharing of contaminated injection equipment and sexual risk behaviors [10].

This HIV/HCV risk environment is epitomized by the outbreak in Scott County, Indiana beginning in late 2014 [11]. HIV incidence, attributed to shared injection equipment, rose from 5 to 181 cases in 2015. Over 90% were co-infected with HCV. Nationally, 2392 new HIV cases in people who inject drugs (PWID) were reported in 2015 [3]. HCV incidence tripled between 2010 and 2015, primarily due to opioid-related drug injection [12]. HIV and HCV prevention efforts for individuals with OUD have been challenged by lack of health insurance [13], limited access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) [14, 15], fragmented care [16], psychiatric co-morbidities [3], and the syndemic nature of these overlapping epidemics where services that are most needed do not exist [16, 17].

The design and scale-up of integrated or co-located, multidisciplinary care models that engage and retain individuals is critical to the success of HIV and HCV prevention strategies [16, 18, 19]. Key components of such models are (1) provision of MAT to reduce risks for acquiring HIV and HCV and to prevent HCV re-infection, (2) HIV and HCV treatment to prevent transmission within injection drug and sexual networks (“treatment as prevention, TasP”), (3) access to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), (4) behavioral health services that address psychiatric co-morbidities and increase engagement with and adherence to care, and (5) access to harm reduction services (i.e., sterile injection equipment and naloxone) [16, 18,19,20,21,22]. This “twenty-first century” opioid epidemic, initially demographically and geographically different from the “twentieth century” one, is characterized by PWID networks among rural, primarily white populations [2, 23, 24], although it has recently extended to urban minority communities [25••]. This means that the delivery of integrated or co-located care will need to be tailored to different populations, geographical locations, and the surrounding, typically resource-poor, healthcare environments [26••].

Understanding models of care that have integrated or co-located HIV, HCV, and OUD services is crucial for optimizing initiatives to expand access to care. This paper presents current models of care within five treatment settings: primary care, HIV care, specialized opioid treatment programs (OTPs), transitional clinics, and community-based harm reduction programs. Program characteristics, as well as a representative model of care for each treatment setting, are described to guide future program development, followed by a discussion of emerging approaches and areas that need further research.

Methods

Search Strategy

We searched the literature describing care models that included MAT (methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone), HIV, and/or HCV services from August 2007 to September 2017 using Ovid Medline, Scopus, PsychInfo, and EMBASE databases for articles and conference abstracts (see Appendix Table S.1 for search terms). We also reviewed reference lists of key papers describing integrated/co-located models of care. To be included, studies had to describe a health service(s) delivery program that (1) was located in the USA, (2) provided MAT, (3) provided HIV and/or HCV care, (4) was designed for adults (≥ 18 years), and (5) was written in English or Spanish.

Data Extraction

Selected studies were classified as describing care provided in one of the five treatment settings listed above. For each model, data were extracted to describe the population(s) served, the OUD treatment agents available, and the extent or co-location of mental healthcare integration and HIV/HCV care.

Selection of Representative Model

For each treatment setting, we selected a representative model of care based on their similarity to other programs within the given category, their innovativeness, or their focus on HIV and/or HCV care.

Results

We identified 1394 abstracts and reviewed 141 full text articles and conference abstracts, of which 41 described 17 unique, co-located or integrated models of care (5 HIV specialty care, 3 primary care, 6 OTP, 2 transitional clinics, and 1 community-based harm reduction program), and two emerging models. Details of each of model of care are provided in the Appendix (Table S.2). General characteristics of the populations served by treatment setting are provided in Table 1. Pharmacological agents used to treat OUD are described in Table 2.

Primary Care

A key strategy to expand access to comprehensive care for individuals with OUD, and thereby decrease the risk of HIV and HCV transmission, is the integration or co-location of treatment for all three conditions into primary care settings [26••], particularly in rural areas that lack specialty opioid and infectious diseases treatment centers. Key advantages of the delivery of OUD, HIV, and HCV treatment in the primary care setting are that this model lowers the threshold for patient entry and enhances continuity of care [27, 28]. As many individuals with opioid misuse or addiction seek treatment for physical ailments, primary care providers (PCPs) play a crucial role in identifying substance use disorders (SUDs) and expanding treatment accessibility [29, 30]. Physicians who complete 8 h of training and nurse practitioners and physician assistants who complete 24 h of training may obtain a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) waiver to prescribe buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone, the mainstay of MAT [31, 32]. In addition to treating OUD, buprenorphine/naloxone also has been shown to reduce HCV reinfection [33]. For individuals with OUD who do not want buprenorphine, any clinician can prescribe extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX), an evidence-based opioid antagonist treatment for OUD that requires successful completion of supervised withdrawal (“detox”) before starting treatment.

Representative Example:

Location

A federally qualified health center (FQHC) affiliated with Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, New York, that serves over 9000 adults annually [34•].

MAT Services

A team of internists and clinical pharmacists conduct screening and onsite buprenorphine/naloxone treatment, including induction, stabilization, and maintenance. Clinical pharmacists, internists, or both together conduct follow-up visits. Motivational interviewing is incorporated into medical visits to promote adherence and engagement in care. Clinical judgment drives urine drug testing (UDT), but no one is discharged from treatment solely due to UDT results [34•, 35•].

Psychiatric Services

Co-located.

HIV Services

Testing and treatment are provided, supported by Ryan White Care Act funding [34•, 35•].

HCV Services

HCV evaluation and treatment are provided by a physician trained in both HCV care and addiction medicine, supported by a care coordinator. Referrals come from PCPs and nearby syringe exchange programs. Treated patients are enrolled in the NYC Department of Health’s Check Hep C Patient Care Coordinator Program which provides a full time care coordinator to facilitate linkage and retention in HCV care, psychosocial assessment, health education, navigation of insurance prior authorization and claims, and applications to patient assistance programs for medication [34•].

HIV Specialty Care Clinics

HCV prevalence among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) is about 25% nationally [36], and HIV/HCV co-infection among PWID ranges between 50 and 90% [37]; both vary by location and population served. Specialty HIV care sites, which typically provide access to infectious disease experts, are an ideal setting to provide integrated or co-located HIV, HCV, and OUD treatments in communities with a high prevalence of HIV among PWID.

Acknowledging the importance of integrating substance use treatment at HIV care sites, the HIV/AIDS Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) funded the Buprenorphine and HIV Care Evaluation and Support (BHIVES) initiative from 2004 to 2009. BHIVES developed and implemented integrated HIV care and buprenorphine/naloxone treatment at ten sites [38]. Qualitative interviews with patients at one site suggest that they felt positively about the provision of MAT at an HIV care site, as it allowed access to OUD treatment in a setting that did not care exclusively for individuals with SUDs. In a longitudinal analysis, HIV patients prescribed and maintained on buprenorphine/naloxone were significantly more likely to be prescribed antiretroviral therapy (ART) and to achieve viral suppression than those not retained on MAT [39]. Key features associated with success at each clinic involved ongoing education and support to providers [40] and a “glue” person who coordinated care for these more complex patients [38].

Representative Example

Location

A hospital-based HIV clinic in Providence, Rhode Island. The clinic cares for 1400 HIV-infected patients, of whom approximately 30% have OUD [41•].

MAT Services

Patients are regularly informed of onsite buprenorphine/naloxone treatment through nurse-led educational sessions and during regularly scheduled HIV care appointments. The clinic also coordinates with nearby substance use treatment facilities.

Psychiatric Services

Psychologists and social workers provide both individual care and support groups [42].

HIV Services

Specialty HIV care is provided by HIV physicians. The clinic, embedded within a hospital facility, provides HIV testing, counseling, treatment, education, and case management [42].

HCV Services

All patients are screened, evaluated, and provided treatment onsite through the HIV program’s co-located Coinfection Clinic [41•].

Specialty OTPs

Opioid treatment programs (OTPs) are federally qualified programs that specialize in methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) [43]. OTPs can be funded either directly or indirectly through public sources or through fee-for-service models. An advantage of MMT in the public setting is that it is usually provided with minimal direct expense to the patient [44]. MMT requires daily visits to receive methadone; although with time and duration of abstinence, patients can take home doses for self-administration [45]. OTPs may also be staffed by other healthcare providers who can provide primary or specialty care for a range of co-morbid psychiatric conditions, HIV and HCV [46•]. HCV-infected individuals who are treated while receiving MAT have achieved high rates of sustained virologic response (SVR, or cure) irrespective of continued drug use [33], underscoring the fact that sobriety should not be a precondition of HCV treatment.

Representative Example

Location

The APT Foundation, a non-profit addiction treatment program in Connecticut, where the majority of patients have an OUD [46•]. Injection equipment disposal boxes are installed in exam rooms.

MAT Services

All patients undergo an initial medical and psychiatric evaluation. The program provides methadone or buprenorphine to over 5000 patients [46•].

Psychiatric Services

Psychiatric care, including psychotherapy, individualized treatment counseling and medication, is available [46•].

HIV Services

HIV testing, counseling, and treatment are provided; referrals can also be made to specialty clinics.

HCV Services

HCV testing, counseling, and treatment are provided. Free voluntary HCV screening is provided, and for those with infection, their contacts may be approached anonymously. There is supportive care from social workers and psychiatrists as needed [46•].

Community-Based Harm Reduction Programs

Syringe service programs (SSPs, also known as syringe or needle exchange programs) are a critical component of HIV, HCV, and overdose prevention [47,48,49,50,51,52]. SSPs provide non-judgmental, free, accessible testing and care services to PWID who often do not have contact with medical services or who shun medical care because of stigma and prior poor treatment [53]. A recent study found that 50% SSP coverage within the USA would be cost-effective and avert up to 35,000 HIV infections over 20 years [54]. For maximal impact, SSPs must provide a robust array of health services [55,56,57], including HIV testing linked to both primary (e.g., sterile equipment, addiction treatment, PrEP) and secondary HIV prevention (e.g., TasP), and HCV testing with linkage to parallel services. A modeling study found that a significant reduction in HIV transmission within a community with an established epidemic requires that SSPs provide multiple services, including linkage to healthcare and MAT [55]. In parallel, a meta-analysis concluded that SSPs that provide only sterile syringes are insufficient to prevent the spread of HCV; rather, SSPs must also provide sterile injection equipment (i.e., cottons, cookers), as well as other harm reduction services (i.e., safe sex, condoms, and sterile injection education) [56]. A network model found that if HCV prevalence within a PWID community is ≤ 60%, then treating ≥ 12% of HCV-positive PWID in the network would eliminate HCV within 10 years [58]. Together, these data support the concept that the ideal SSP is a “one-stop shop” that provides harm reduction, HIV and HCV testing and linkage to services and linkage to OUD treatment services.

Representative Example

Location

A mobile medical clinic and an associated fixed site clinic in Connecticut. Bilingual (English/Spanish) case managers provide outreach services using a minivan [59•].

Harm Reduction Services

Sterile injection equipment, condoms, and rapid HIV and HCV testing are provided at both sites. Naloxone, overdose prevention education, and safe sex education are offered at each visit.

MAT Services

Maintenance with buprenorphine/naloxone or naltrexone (XR-NTX) is provided at both sites.

Psychiatric Services

Social workers and psychiatric nurse practitioners provide mental health counseling at the fixed site clinic.

HIV Services

HIV treatment and case management is provided at both sites, and ART is dispensed as directly administered therapy [59•]. There are no specialty services for complicated HIV patients; however, linkage to off-site specialty HIV care is available.

HCV Services

Rapid HCV tests are provided. Outreach workers provide case management services and linkage to HCV treatment.

Transitional Clinics

Individuals transitioning from criminal justice settings (CJS) back to the community have a disproportionately high prevalence of HIV, HCV, substance use, and psychiatric illness (for review, see [60]). One in six PLWH transitions through a prison or jail annually [61]. While most PLWH achieve viral suppression within the CJS [62], linkage to and retention in care post-release are suboptimal [63], with relapse to drug and alcohol use associated with poor ART adherence and retention in care [64]. Moreover, release from prison is associated with extraordinary mortality primarily due to overdose fatality, especially within the first 2 weeks post-release.

Like HIV, people with HCV are concentrated in CJS; 11 to 37% have HCV, representing 30% of the estimated 5.7 to 6.5 million cases in the USA [65]. HCV treatment within prison has been feasible with good outcomes [66], and newer data using direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) in New York confirm earlier findings [67]. Nonetheless, in 2015, less than 1% of prisoners known to be HCV-positive were provided treatment while incarcerated, largely due to the high cost of DAA and limited funding for treatment [68]. Accordingly, many inmates with untreated HCV transition into the community, challenging linkage to care efforts and potentially fueling onward HCV transmission, undermining both the health of the individual and the community.

This evidence underscores the importance of transitional clinics specifically designed to care for individuals who have recently been released from incarceration, with the aim of optimizing care coordination between the CJS and the community. Transitional clinics can increase engagement and retention in care and will have the greatest impact in communities with high rates of incarceration. Importantly, this model may help address current racial disparities in access to HIV, HCV, and OUD care, as well as treatment outcomes among black individuals, who have the highest rate of new HIV infections and AIDS diagnoses [69].

Representative Example

Location

The Bronx Transitions Clinic (BTC) operates an “open access” clinic from an federally qualified health center (FQHC) affiliated with Montefiore Medical Center. The program is a collaboration between the clinic and the Osborne Association, a community-based organization that screens inmates for chronic health conditions and initiates case management while they are still incarcerated. The BTC provides a range of services on a sliding fee scale. Specific educational programs help facilitate community reentry. Formerly incarcerated community health workers are employed to provide health education, social support, and care coordination [70•, 71•].

MAT Services

All individuals with OUD are offered buprenorphine/naloxone.

Psychiatric Services

Provided onsite.

HIV Services

ART and case management are provided; approximately 20% are HIV-positive. The Osborne Association provides case management through outreach workers.

HCV Services

Treatment is provided onsite.

Emerging Models

The volatile nature of the opioid epidemic, its associated risk of new HIV and HCV outbreaks, the availability of new, effective treatments, and the rural location of many PWID necessitate the development of innovative care models. Expanded access to care in rural areas is desperately needed.

In 2012, it was estimated that state-level rates of buprenorphine treatment capacity ranged from 0.7 to 13.8 patients per 1000 individuals aged 12 years or older [72]. All but two states had a rate of past year OUD greater than their treatment capacity rate, resulting in an enormous gap between treatment need and capacity of 1.4 million people [72]. A survey of 108 PCPs in 2014 found that while 80% reported that they knew of opioid-dependent patients and 73% admitted to feeling a personal responsibility as a primary care doctor to treat addiction, only 10% prescribed MAT [73]. The most commonly cited reasons for not providing MAT was the belief that treating addiction is difficult, a lack of confidence in prescribing according to guidelines, and a low level of staff preparedness. Similar barriers exist for the provision of HIV and HCV care, particularly for individuals with OUD [74,75,76].

A second factor contributing to the treatment gap is the changing demographic characteristics and geographic distribution of individuals with OUD [23, 77•]. Historically, opioid use was largely concentrated in urban areas among minority populations, whereas currently it is concentrated among primarily white populations in suburban and rural areas [23]. In an analysis of county-level vulnerability to HIV and HCV infections, 220 rural counties were defined as vulnerable [77•], reflecting the changing geographic distribution of both opioid misuse and addiction, and the associated increase of IDU.

There are two emerging models of care that hold promise for expanding access to integrated care services by utilizing internet and cell phone technologies: Project ECHO (a tele-education program) [78] and a A-CHESS (an mHealth phone application) [79•].

Telemedicine and Tele-education

Standard telemedicine via two-way videoconferencing permits direct interaction between patients and specialists in different locations. It is an adaption of the traditional brick-and-mortar “hub and spoke model”, in which a specialty care center provides support and resources to several lower-tier care centers throughout a geographic area.

Project Extension for Community Care Outcomes (Project ECHO), a tele-education model developed at the University of New Mexico, utilizes videoconference technology to help PCPs gain the knowledge and self-efficacy to deliver complex specialty medical care. A group of interdisciplinary specialists located at a distant “hub” video links with community PCPs for regularly scheduled didactic sessions and case presentations. ECHO creates “knowledge networks” that promote learning and the rapid dissemination of current treatment research and epidemiological trends [80]. It has been proven effective for HCV treatment and has been applied to a range of other conditions [80,81,82]. An Integrated Addictions and Psychiatry Tele-ECHO clinic has recruited physicians to complete the 8-h buprenorphine training, thus allowing them to provide MAT. Since 2006, over 175 physicians in New Mexico have completed training through this program [80]. Tele-education may be particularly useful in rural or other underserved areas where access to specialty care or academic medical centers is limited.

mHealth Phone Apps

mHealth—the use of mobile apps and text messaging to promote health—has grown dramatically in the past decade. While mHealth approaches lack rigorous evaluation and are still early in development, mHealth holds the promise of providing cost-effective tools to manage care and promote health behaviors [83,84,85]. mHealth can provide a private communication platform that permits flexible reminders and content [86,87,88]. mHealth acceptability has been investigated among people who use drugs (PWUD) and are engaged in HIV or SUD treatment [88]. Results suggest that the majority of PWUD are interested in mHealth to promote health and adherence to HIV treatment. In the context of HIV, HCV, and OUD care, mHealth apps provide a platform to virtually integrate care by facilitating communication and the dissemination of information between patients and providers with potential to increase care coordination, both between care teams from different clinics and among team members at a clinic with co-located services. This approach, however, is limited by cost (usage of minutes) and lack of cell phone coverage in some rural areas.

A-CHESS is a smartphone app designed by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is being evaluated for reducing illicit opioid use among individuals receiving MAT [79]. The app provides a platform for information sharing and SUD treatment support tools, such as cognitive behavioral therapy booster sessions; GPS-based location monitoring to predict locations that may place the individual at risk of drug use or unsafe sex; a “help” button that shows a list of preapproved supports including phone numbers; and distractive activities. For participants who are HIV and/or HCV positive, A-CHESS delivers health education content, and links to clinical care/case-management services. While still in development, it is a promising mHealth strategy to coordinate a patchwork of treatment services and support, especially in rural areas.

Research Gaps and Future Directions

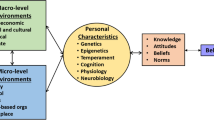

Our review identified several areas with limited information. The development of strategies to increase communication and teamwork across care teams may increase retention and success in care and may be more rewarding to both patients and practitioners. This is particularly important for the expansion of care in rural communities. Research is needed on optimal approaches to delivering harm reduction services in isolated rural communities, as well as strategies to effectively fold addiction, HIV, and HCV care into rural primary care practices that may already be overburdened and under-resourced. While tele-education has proven to be an exciting and effective strategy, additional research is needed to identify best practices and limitations, especially in areas without reliable internet access. Figure 1 depicts the potential pathway of integration from separate specialty clinics to a model of integrated care, supported by tele-education platforms.

Secondly, no studies have evaluated differing levels of engagement across racial, ethnic, and gender groups. Data are needed to better engage and care for diverse populations to prevent HIV and HCV among individuals with OUD. Work is especially needed to address the deleterious racial and ethnic legacies of the “War on Drugs”, as well as the pervasive stigma and distrust surrounding treatment—both for addiction and mental health care.

Third, research is needed to inform the delivery and integration or co-location of psychiatric care for a population with OUD and other co-morbidities. Information on how to best treat anxiety and depression among individuals with OUD and HIV is needed to inform treatment paradigms that do not exacerbate substance use, such as combined opioid and benzodiazepine dependence. Another significant barrier to the scale-up of integrated models of care is cost. To address this, future studies should consider including a budget impact analysis as part of the evaluation process. At a system-level approach, health insurance and payment reform are needed to allow reimbursement for care by mid-level practitioners, outreach workers, and peer navigators within integrated or co-located models of care, as well as telemedicine services.

Finally, increasing access to harm reduction services is essential to preventing HIV and HCV, including access to sterile injection equipment and a range of treatment options for OUD and HIV/HCV. Expansion of funding and political support is needed for developing innovative harm reduction programs, including pharmacy-based syringe exchange and increased provision of syringe prescriptions by clinicians.

Limitations

Our review has several limitations. Due to the nature of a literature search, our description of care models is biased toward interventions connected with academic research institutions. While we included conference abstracts and searched the “gray literature” (materials and research produced by organization outside of traditional peer-reviewed academic publishing) for descriptions of care models not fully described in peer-reviewed articles, our search may not have captured all integrated or co-located treatment paradigms. Secondly, we restricted our search to models of care within the USA to provide examples of models most relevant to the current opioid epidemic. International programs, however, provide other examples of effective care models. Future research should look to incorporating aspects of successful international models to inform program development in the USA. Lastly, none of the models explicitly addressed provision of PrEP.

Conclusion

The design and scale-up of integrated or co-located, multidisciplinary care models that engage and retain individuals in HIV, HCV, OUD, and mental health care are critical to preventing the continued spread of HIV and HCV in the context of the current opioid epidemic. Key components of such care models are the provision of (1) MAT to reduce the risk for HIV and HCV acquisition and to prevent HCV re-infection, (2) HIV and HCV treatment to prevent transmission through shared injection equipment and unsafe sex, (3) access to PrEP and to syringe services programs to prevent HIV and HCV, and (4) behavioral health services to address psychiatric co-morbidities. Communities in different locales may require different models. Examples of current models of care in five critical settings—primary care, HIV care, OPT/MAT, harm reduction programs, and transitional clinics—provide a good starting point for future innovation.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Wang X, Zhang T, Ho W-Z. Opioids and HIV/HCV infection. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. Off. J Soc NeuroImmune Pharmacol 2011;6:477–89.

Van Handel MM, Rose CE, Hallisey EJ, Kolling JL, Zibbell JE, Lewis B, et al. County-level vulnerability assessment for rapid dissemination of HIV or HCV infections among persons who inject drugs, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2016;73:323–31.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and injection drug use [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/idu.html

Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, Rhodes T, Booth R, Abdool R, et al. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2010;376:268–84.

Mars SG, Bourgois P, Karandinos G, Montero F, Ciccarone D. “Every ‘never’ I ever said came true”: transitions from opioid pills to heroin injecting. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2014;25:257–66.

Lenardson JD, Smith ML. Catastrophic consequences: the link between rural opioid use and HIV/AIDS. HIV/AIDS rural communities [Internet]. Springer, Cham; 2017 [cited 2017 Sep 22]. p. 89–108. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-56239-1_7

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 17-45044, NSDUH Series H-52) [Internet]. Rockville, MD; 2017. Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Lankenau SE, Teti M, Silva K, Bloom JJ, Harocopos A, Treese M. Patterns of prescription drug misuse among young injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2012;89:1004–16.

Neaigus A, Miller M, Friedman SR, Hagen DL, Sifaneck SJ, Ildefonso G, et al. Potential risk factors for the transition to injecting among non-injecting heroin users: a comparison of former injectors and never injectors. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2001;96:847–60.

Perlman DC, Des Jarlais DC, Feelemyer J. Can HIV and HCV infection be eliminated among persons who inject drugs? J Addict Dis. 2015;34:198–205.

Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW, Patel MR, Galang RR, Shields J, et al. HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014-2015. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:229–39.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis surveillance report [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2017/hepatitis-surveillance-report.html

Underhill K. Paying for prevention: challenges to health insurance coverage for biomedical HIV prevention in the United States. Am J Law Med. 2012;38:607–66.

Kresina TF, Lubran R. Improving public health through access to and utilization of medication assisted treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:4102–17.

Metzger DS, Donnell D, Celentano DD, Jackson JB, Shao Y, Aramrattana A, et al. Expanding substance use treatment options for HIV prevention with buprenorphine-naloxone: HIV Prevention Trials Network 058. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1999. 2015;68:554–61.

Reece R, Dugdale C, Touzard-Romo F, Noska A, Flanigan T, Rich JD. Care at the crossroads: navigating the HIV, HCV, and substance abuse syndemic. Fed. Pract. Health Care Prof. VA DoD PHS. 2014;31:37S–40S.

Morano JP, Gibson BA, Altice FL. The burgeoning HIV/HCV syndemic in the urban northeast: HCV, HIV, and HIV/HCV coinfection in an urban setting. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64321.

Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2010;376:367–87.

Madras BK. The surge of opioid use, addiction, and overdoses: responsibility and response of the US health care system. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:441–2.

Hagan H, Pouget ER, Des Jarlais DC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to prevent hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugs. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:74–83.

MacArthur GJ, van Velzen E, Palmateer N, Kimber J, Pharris A, Hope V, et al. Interventions to prevent HIV and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: a review of reviews to assess evidence of effectiveness. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:34–52.

Patel V, Belkin GS, Chockalingam A, Cooper J, Saxena S, Unützer J. Grand challenges: integrating mental health services into priority health care platforms. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001448.

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:821–6.

Dombrowski K, Crawford D, Khan B, Tyler K. Current rural drug use in the US Midwest. J. Drug Abuse [Internet]. 2016;2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5119476/

•• Shiels MS, Freedman ND, Thomas D, de Gonzalez AB. Trends in U.S. drug overdose deaths in non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white persons, 2000-2015. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017; Shiels and colleagues present national rates of drug use across non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white individuals by drug type .

•• Korthuis PT, McCarty D, Weimer M, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Zakher B, et al. Primary care-based models for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a scoping review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017;166:268–78. A systematic overview of models to integrate OUD treatment into primary care .

O’Connor PG, Oliveto AH, Shi JM, Triffleman EG, Carroll KM, Kosten TR, et al. A randomized trial of buprenorphine maintenance for heroin dependence in a primary care clinic for substance users versus a methadone clinic. Am J Med. 1998;105:100–5.

Barry DT, Irwin KS, Jones ES, Becker WC, Tetrault JM, Sullivan LE, et al. Integrating buprenorphine treatment into office-based practice: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:218–25.

Mersy DJ. Recognition of alcohol and substance abuse. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:1529–32.

Muhrer J. Detecting and dealing with substance abuse disorders in primary care. J. Nurse Pract. [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2017 Feb 19]; Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251689997_Detecting_and_Dealing_with_Substance_Abuse_Disorders_in_Primary_Care

ASAM. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants prescribing buprenorphine [Internet]. [cited 2017 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.asam.org/resources/practice-resources/nurse-practitioners-and-physician-assistants-prescribing-buprenorphine

SAMHSA. Buprenorphine waiver management [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/buprenorphine-waiver-management

Dore GJ, Altice F, Litwin AH, Dalgard O, Gane EJ, Shibolet O, et al. Elbasvir-Grazoprevir to treat hepatitis C virus infection in persons receiving opioid agonist therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:625–34.

• Norton BL, Beitin A, Glenn M, DeLuca J, Litwin AH, Cunningham CO. Retention in buprenorphine treatment is associated with improved HCV care outcomes. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2017;75:38–42. Norton and colleagues describe a primary care clinic that provides care for HIV, HCV, and OUD, which provide an updated data and discussion regarding the program presented by Cunningham et al. (2008) .

• Cunningham C, Giovanniello A, Sacajiu G, Whitley S, Mund P, Beil R, et al. Buprenorphine treatment in an urban community health center: what to expect. Fam. Med. 2008;40:500–6. Cunningham and colleagues present a primary care clinic that provides OUD treatment within an urban setting .

CDC. HIV/AIDS and Viral Hepatitis [Internet]. HIV/AIDS and viral hepatitis [Internet]. 2017 Sep. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/populations/hiv.htm

Walsh N, Maher L. HIV and viral hepatitis C coinfection in people who inject drugs: current opinion in HIV and AIDS. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 7:339–44.

Weiss L, Netherland J, Egan JE, Flanigan TP, Fiellin DA, Finkelstein R, et al. Integration of buprenorphine/naloxone treatment into HIV clinical care: lessons from the BHIVES collaborative. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 1999 2011;56 Suppl 1:S68–75.

Altice FL, Bruce RD, Lucas GM, Lum PJ, Korthuis PT, Flanigan TP, et al. HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected, opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone treatment within HIV clinical care settings: results from a multisite study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1999. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S22–32.

Egan JE, Netherland J, Gass J, Finkelstein R, Weiss L, Collaborative B. Patient perspectives on buprenorphine/naloxone treatment in the context of HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:S46–53.

• Taylor LE, Maynard MA, Friedmann PD, Macleod CJ, Rich JD, Flanigan TP, et al. Buprenorphine for human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients: does it serve as a bridge to hepatitis C virus therapy? J. Addict. Med. 2012;6:179–85. Taylor and colleagues describe the provision of OUD treatment within a clinic providing HIV and HCV specialty care .

Rhode Island AIDS and HIV care at the Miriam Hospital [Internet]. [cited 2017 Oct 24]. Available from: https://www.lifespan.org/centers-services/aidshiv-immunology-center

Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23:63–75.

Bart G. Maintenance medication for opiate addiction: the foundation of recovery. J Addict Dis. 2012;31:207–25.

Schuckit MA. Treatment of opioid-use disorders. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1596–7.

• Butner JL, Gupta N, Fabian C, Henry S, Shi JM, Tetrault JM. Onsite treatment of HCV infection with direct acting antivirals within an opioid treatment program. J Subst Abus Treat. 2017;75:49–53. Butner and colleagues present data on the provision of HCV treatment at a specialty opioid treatment program

Watters JK, Estilo MJ, Clark GL, Lorvick J. Syringe and needle exchange as HIV/AIDS prevention for injection drug users. JAMA. 1994;271:115–20.

Kaplan EH, Heimer RA. Circulation theory of needle exchange. [Editorial]. AIDS. 1994;8:567–74.

Heimer R, Lopes M. Syringe and needle exchange to prevent HIV infection. JAMA. 1994;271:1825–6. author reply 1826-1827

Vermund SH. Global HIV epidemiology: a guide for strategies in prevention and care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11:93–8.

Pouget ER, Hagan H, Des Jarlais DC. Meta-analysis of hepatitis C seroconversion in relation to shared syringes and drug preparation equipment. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 2012;107:1057–65.

Roux P, Rojas Castro D, Ndiaye K, Debrus M, Protopopescu C, Le Gall J-M, et al. Increased uptake of HCV testing through a community-based educational intervention in difficult-to-reach people who inject drugs: results from the ANRS-AERLI Study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157062.

Clark AK, Wilder CM, Winstanley EL. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J Addict Med. 2014;8:153–63.

Bernard CL, Owens DK, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Brandeau ML. Estimation of the cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention portfolios for people who inject drugs in the United States: a model-based analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002312.

Marshall BDL, Friedman SR, Monteiro JFG, Paczkowski M, Tempalski B, Pouget ER, et al. Prevention and treatment produced large decreases in HIV incidence in a model of people who inject drugs. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33:401–9.

Davis SM, Daily S, Kristjansson AL, Kelley GA, Zullig K, Baus A, et al. Needle exchange programs for the prevention of hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugs: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14:25.

Uyei J, Fiellin DA, Buchelli M, Rodriguez-Santana R, Braithwaite RS. Effects of naloxone distribution alone or in combination with addiction treatment with or without pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in people who inject drugs: a cost-effectiveness modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e133–40.

Zelenev A, Li J, Mazhnaya A, Basu S, Altice FL. Hepatitis C virus treatment as prevention in an extended network of people who inject drugs in the USA: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;

• Sylla L, Bruce RD, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Integration and co-location of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and drug treatment services. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2007;18:306–12. The paper provides a description of a mobile medical clinic providing HIV treatment and harm reduction services

Wakeman SE, Rich JD. HIV treatment in US prisons. HIV Ther. 2010;4:505–10.

Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releases from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7558.

Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2004;38:1754–60.

Loeliger KB, Altice FL, Desai MM, Ciarleglio MM, Gallagher C, Meyer JP. Predictors of linkage to HIV care and viral suppression after release from jails and prisons: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet HIV 2017;

Althoff AL, Zelenev A, Meyer JP, Fu J, Brown S-E, Vagenas P, et al. Correlates of retention in HIV care after release from jail: results from a multi-site study. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:156–70.

Varan AK, Mercer DW, Stein MS, Spaulding AC. Hepatitis C seroprevalence among prison inmates since 2001: still high but declining. Public Health Rep. 2014;129:187–95.

Maru DS-R, Bruce RD, Basu S, Altice FL. Clinical outcomes of hepatitis C treatment in a prison setting: feasibility and effectiveness for challenging treatment populations. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2008;47:952–61.

MacDonald R, Akiyama MJ, Kopolow A, Rosner Z, McGahee W, Joseph R, et al. Feasibility of treating hepatitis C in a transient jail population. Open Forum Infect. Dis. [Internet]. 2017;4. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5569928/

Beckman AL, Bilinski A, Boyko R, Camp GM, Wall AT, Lim JK, et al. New hepatitis C drugs are very costly and unavailable to many state prisoners. Health Aff. Proj. Hope. 2016;35:1893–901.

CDC. HIV among African Americans [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/index.html

• Fox AD, Anderson MR, Bartlett G, Valverde J, MacDonald RF, Shapiro LI, et al. A description of an urban transitions clinic serving formerly incarcerated people. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25:376–82. The paper presents a care model providing HIV, HCV, and OUD treatment for individuals transitioning from the criminal justice system to an urban community .

• Fox AD, Anderson MR, Bartlett G, Valverde J, Starrels JL, Cunningham CO. Health outcomes and retention in care following release from prison for patients of an urban post-incarceration transitions clinic. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25:1139–52. The paper provides data on health outcomes and retention in care from the clinic described by Fox et al. 2014a .

Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, McCance-Katz E. National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e55–63.

DeFlavio JR, Rolin SA, Nordstrom BR, Kazal LAJ. Analysis of barriers to adoption of buprenorphine maintenance therapy by family physicians. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15:3019.

Treloar C, Rance J, ETHOS Study Group. How to build trustworthy hepatitis C services in an opioid treatment clinic? A qualitative study of clients and health workers in a co-located setting. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2014;25:865–70.

Yehia BR, Schranz AJ, Umscheid CA, Iii VLR. The treatment cascade for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101554.

Bini EJ, Kritz S, Brown LS, Robinson J, Alderson D, Rotrosen J. Barriers to providing health services for HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C virus infection and sexually transmitted infections in substance abuse treatment programs in the United States. J Addict Dis. 2011;30:98–109.

•• Van Handel MM, Rose CE, Hallisey EJ, Kolling JL, Zibbell JE, Lewis B, et al. County-level vulnerability assessment for rapid dissemination of HIV or HCV infections among persons who inject drugs, United States: JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016;73:323–31. Geospatial analysis of communities vulnerable to an HIV or HCV outbreak .

Talal A, Andrews P, McLeod A, Zeremski M, Chen Y, Sylvester C, et al. Integrated, co-located, telemedicine-based treatment approaches for hepatitis C virus (HCV) management for individuals on opioid agonist treatment. J Hepatol. 2016;64:S747.

• Gustafson DH, Landucci G, McTavish F, Kornfield R, Johnson RA, Mares M-L, et al. The effect of bundling medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction with mHealth: study protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2016;17:592. Gustafson and colleagues describe the A-CHESS mHealth app, an innovation to decrease illicit opioid use among individuals receiving medication-assisted treatment .

Komaromy M, Duhigg D, Metcalf A, Carlson C, Kalishman S, Hayes L, et al. Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes): a new model for educating primary care providers about treatment of substance use disorders. Subst Abuse. 2016;37:20–4.

• Arora S, Kalishman S, Thornton K, Dion D, Murata G, Deming P, et al. Expanding access to hepatitis C virus treatment—Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project: disruptive innovation in specialty care. Hepatol. Baltim. Md. 2010;52:1124–33. This paper describes a tele-education model (Project ECHO) that aims to increase provision of HCV treatment in underserved areas, particularly among communities with high rates of OUD .

Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, Deming P, Kalishman S, Dion D, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2199–207.

Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:165–73.

Lim MSC, Hocking JS, Hellard ME, Aitken CK. SMS STI: a review of the uses of mobile phone text messaging in sexual health. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:287–90.

Katz DL, Nordwall B. Novel interactive cell-phone technology for health enhancement. J Diabetes Sci Technol Online. 2008;2:147–53.

Smith A. Record shares of Americans now own smartphones, have home broadband [Internet]. Pew Res. Cent. 2017 [cited 2017 Sep 6]. Available from: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/01/12/evolution-of-technology/

Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, Kariri A, Karanja S, Chung MH, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2010;376:1838–45.

Horvath KJ, Lammert S, LeGrand S, Muessig KE, Bauermeister JA. Using technology to assess and intervene with illicit drug-using persons at risk for HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12:458–66.

Hser Y-I, Evans E, Grella C, Ling W, Anglin D. Long-term course of opioid addiction. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 2015;23:76–89.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kate Nyhan for her invaluable advice during the design of the literature review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on The Global Epidemic

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 67 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rich, K.M., Bia, J., Altice, F.L. et al. Integrated Models of Care for Individuals with Opioid Use Disorder: How Do We Prevent HIV and HCV?. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 15, 266–275 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-018-0396-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-018-0396-x