Abstract

Management literature is currently giving growing conceptual and empirical attention to the peculiarity and relevance of entrepreneurial attitudes in family firms, with divergent outcomes. Aiming at concretizing the effects of these attitudes, denoted by the entrepreneurial orientation construct, on family business performance and considering that family dynamics come into play in this relationship, we particularly investigate the impact of control mechanisms and family-related goals. Findings are based on a sample of 180 family firms and show that Proactiveness and Autonomy are particularly relevant to financial performance. Agency-problems avoiding control mechanisms moderate the effect of Innovativeness and Autonomy, while socioemotional wealth (SEW) goals moderate the effect of Risk-Taking, respectively. The usage of these mechanisms and managing SEW goals provide opportunities for a more efficient exploitation of entrepreneurial attitudes.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Entrepreneurial attitudes are decisive for a business to strategically renew (Chua et al. 1999), grow and perform well (Schumpeter 1934). To determine these attitudes, the entrepreneurial literature foremost applies the entrepreneurial orientation (EO) construct and its widely accepted positive relationship to financial firm performance (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Miller 1983; Wales et al. 2013).

In family firms, family-related interests impact the effect of entrepreneurial attitudes on financial performance (Nordqvist et al. 2008; Kraus et al. 2012c). Attempts to transmit the EO-performance relationship to family firms have been pursued, predominantly by analyzing the effect of particular EO dimensions from the multidimensional construct on financial performance (e.g. Lumpkin et al. 2009; De Massis et al. 2014; Naldi et al. 2007; Bouncken et al. 2016), by focusing on growth as the performance measure (Casillas and Moreno 2010), by investigating effects of management composition (Sciascia et al. 2013), or by investigating the moderating effect of Socio-Emotional Wealth (SEW) on the unidimensional EO-performance relationship (Schepers et al. 2014). Despite the importance to understand how entrepreneurial attitudes take effect in family firms, there is not yet a concordant opinion on the transmission of the multidimensional EO construct on family firm performance (Zellweger and Sieger 2012; Kallmuenzer 2015).

Furthermore, an understanding of how entrepreneurial companies control and manage the influence of family firm dynamics (Senftlechner and Hiebl 2015) is still missing. Prior research used numerous theoretical perspectives (Nordqvist et al. 2015) to capture these dynamics, predominantly by taking on agency and stewardship theory perspectives (Eddleston et al. 2010; Le Breton-Miller et al. 2011) or by developing own theoretical constructs such as SEW (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). Family dynamics were often aimed to be understood through their role in corporate governance mechanisms and firm goals (Calabrò and Mussolino 2013; Gnan et al. 2015; Songini and Gnan 2015; Jaskiewicz and Klein 2007).

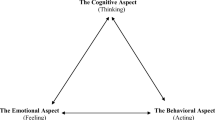

Combining approaches from prior research, in this study we aim at developing a more precise understanding of the effects of entrepreneurial attitudes on family business performance by investigating the moderating influence of control mechanisms and family-related goals. While control mechanisms are employed “to make sure that the goals of the organizational level are reached” (Helsen et al. 2016, p. 3), family-related SEW goals, such as keeping firm control in the family or passing on the firm to the next generation, need to be managed to balance firm- and family preferences (Berrone et al. 2012).

The study is based on survey data of 180 family firm managers in Western Austria and contributes to the literature on entrepreneurship and family businesses: First, we demonstrate how distinct entrepreneurial attitudes of family firms impact financial performance by transmitting the EO-performance relationship. Second, we are able to underline efficient practices to control family dynamics (alongside business dynamics; Nordqvist et al. 2008), and offer insights on how to exploit EO to optimize financial performance while securing a healthy level of family goals. Third, this study extends our knowledge on the relevance of agency control mechanisms in family business. It also adds to the discourse on SEW by testing previously suggested scales from family business literature (Berrone et al. 2012) and demonstrating their applicability as management tools in family firms.

The structure of this article is as follows: First, we elaborate on the theoretical background of the EO-performance relationship in family firms and develop the research framework and hypotheses. Second, we display the research design and outline sample characteristics. Third, we present the empirical results. Fourth, we discuss and interpret these findings. Fifth and concluding, we develop theoretical and practical implications and state the limitations of the study.

2 Theoretical foundation

2.1 Entrepreneurial orientation and family business performance

In corporate entrepreneurship (CE) literature, the EO construct as “part of a CE strategy” (Wales 2016, p. 2) is predominantly considered to consist either of the three dimensions Innovativeness, Proactiveness, and Risk-Taking (e.g. Covin and Slevin 1989), constituting a unidimensional construct where all dimensions have to be present for an EO to exist, or of the five dimensions, adding Autonomy and Competitive Aggressiveness (Lumpkin and Dess 1996), constituting a multidimensional construct where not all dimensions have to be present simultaneously for an EO to exist. This multidimensional EO construct is characterized by “a propensity to act autonomously, a willingness to innovate and take risks, and a tendency to be aggressive toward competitors and proactive relative to marketplace opportunities” (Lumpkin and Dess 1996, p. 137). Both construct variations of EO are assumed to positively affect financial performance (Wales et al. 2013), which usually is measured in terms of profitability, sales growth or other financial measures (Lumpkin and Dess 1996, 2001)

Family-related interests influence the importance of EO dimensions and their effect on performance in family firms (Nordqvist et al. 2008; Kraus et al. 2012a; Xi et al. 2013). For the purpose of this study, we define family firms as firms where ownership and management is aligned within one or more families (i.e., family members of the owning family/-ies are involved in managing the firm), owning family/-ies hold more than 50% of shares, and at least two family members are active in the firm (Miller et al. 2007; Westhead and Cowling 1998; O’Boyle et al. 2012; Steiger et al. 2015). Previous studies show, for example, that, in comparison to their non-family counterparts, family firms do business rather risk-averse (Naldi et al. 2007), and less aggressive, unless threatened (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007), due to image and reputation reasons (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013). Their business behavior is influenced by the goals to protect the longevity of the family firm (Zellweger et al. 2012) and the will to pass on the firm to the next generation for their own and the family’s interest (Berrone et al. 2012). In comparison to non-family firms, studies demonstrate that family firms show similar attitudes for other EO dimensions and their positive effect on financial performance, with regards to Innovativeness (Kellermanns et al. 2012a; Zellweger et al. 2012; Bergfeld and Weber 2011; Kraus et al. 2012b), Proactiveness (De Massis et al. 2014; Zellweger and Sieger 2012; Nordqvist et al. 2008) and Autonomy (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007; Habbershon and Pistrui 2002). However, research findings also indicate that EO dimensions in family firms might have to be refined, to external and internal components of Innovativeness and Autonomy (Nordqvist et al. 2008; Zellweger and Sieger 2012), to different components or definitions of Risk-Taking (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007; Zellweger and Sieger 2012; Zahra 2005), with regards to the applicability of Competitive Aggressiveness (Nordqvist and Melin 2010; Lumpkin et al. 2010; Kallmuenzer and Peters 2017) or depending on the age/generational context for Proactiveness (De Massis et al. 2014; Martin and Lumpkin 2003).

2.2 Control mechanisms

Literature on the use of control mechanisms in family business research is scarce (Helsen et al. 2016; Mitter et al. 2014). Drawing on accounting literature (e.g. Malmi and Brown 2008), the research at hand employs Abernethy and Chua’s (1996) definition of control mechanisms as systems “designed and implemented by management to increase the probability that organizational actors will behave in ways consistent with the objectives of the dominant organizational coalition” (p. 573). So far, prior family business research predominantly addressed the use of control mechanisms from an agency theory perspective (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Schulze et al. 2001). Agency problems were found to harm family business performance (Schulze et al. 2001) and thus need to be controlled (Senftlechner and Hiebl 2015; Helsen et al. 2016).

In general management, agency problems arise due to individuals being self-interested and making decisions upon rational thinking and oriented to own preferences. When ownership and management is separated, agency problems occur due to different preferences and information asymmetries of the owner (principal) and the employed management (agent) (Jensen and Meckling 1976). As a consequence, employees take decisions based on their individual preferences (e.g. short-term, financial gains) instead of the owners’ preferences (e.g. long-term, sustainable development) (Malmi and Brown 2008). Therefore, according to Jensen and Meckling (1976) agency problems in family firms are not existent due to the alignment of ownership and management with the same person or family, avoiding information asymmetries (Senftlechner and Hiebl 2015).

However, more recent family business research has argued against Jensen and Meckling’s (1976) conclusion. Instead of being inexistent, agency problems in family firms stem from different antecedents and thus appear differently. In family firms, agency problems occur due to self-control issues, as well as altruistic and relational preferences of family managers (Schulze et al. 2001, 2003; Mustakallio et al. 2002; Poppo and Zenger 2002). These preferences mostly result from goals to keep firm control and family wealth. Finally, agency problems result from moral hazard and adverse selection due to information asymmetries between family members and an abuse of the strong family relationships (Schulze et al. 2001). These sources of agency problems were found to lower a family firm’s financial performance (Schulze et al. 2001, 2003).

It is therefore necessary to minimize opportunism and agency behavior also in family firms and align individual preferences with firm goals (Fama and Jensen 1983). We follow the idea to address agency problems by the use of control mechanisms (Calabrò and Mussolino 2013; Gnan et al. 2015). Therefore, control mechanisms are developed on the assumption that agency behavior can be controlled through monitoring and peer evaluation (Chrisman et al. 2007; Sieger et al. 2013; Malmi and Brown 2008).

2.3 Family-related goals

To further integrate family business specific preferences such as dynastic succession or the development of social ties (Berrone et al. 2012), we consider family-related goals as a relevant alternative factor impacting family business performance (Gnan et al. 2015). For these behavior-guiding goals we draw on the SEW construct (Berrone et al. 2012; Kellermanns et al. 2012b; Berrone et al. 2010; Cesinger et al. 2016). SEW consists of goals that assure maintaining the family spirit over generations, such as the identification of family members with the firm, emotional attachment of family members, and renewal of family bonds to the firm (Berrone et al. 2012). These goals are key drivers for the survival of family firms and guide the business behavior of family firm managers. As this behavior directly affects firm performance (Schulze et al. 2001), adherence to these goals needs to be managed by matching individual and firm preferences.

2.4 Hypotheses development

2.4.1 The EO-performance relationship

Literature on the five dimensions Innovativeness, Proactiveness, Risk-Taking, Autonomy and Competitive Aggressiveness of the multidimensional EO construct in family firms shows divergent results for their effects on financial performance (Zellweger and Sieger 2012). Authors predominantly argue that Innovativeness is an important driver also for financial performance of family firms, especially when the family is strongly involved (Bergfeld and Weber 2011; Kellermanns et al. 2012a). Proactiveness fosters financial performance (Casillas et al. 2010), but is depending on the age of the firm (De Massis et al. 2014) and only occurs during selected moves (Martin and Lumpkin 2003). Findings on Risk-Taking diverge with regards to its presence in family firms (Hiebl 2013) and the effect on performance (Zahra 2005; Naldi et al. 2007). Autonomy positively influences financial performance in family firms (Habbershon and Pistrui 2002), especially the independence from stakeholders is considered important (Zellweger and Sieger 2012). Competitive Aggressiveness is divergently discussed: While family firms aim at a positive reputation and image in society (Jaskiewicz et al. 2015) and therefore compete less aggressively, they strongly defend their family business when being threatened (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). Due to the divergent and scattered findings for the respective EO dimensions and their effects on performance, we believe that it is necessary to test the complete multidimensional EO-performance relationship (Lumpkin and Dess 1996) for a more integrated understanding.

More detailed, we follow findings from previous research in the field of small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) and family firms (e.g., Lumpkin and Dess 2001; Rigtering et al. 2013; Bouncken et al. 2015), highlighting the importance and mostly direct positive performance effect of having the will to be innovative and of being proactive relative to marketplace opportunities. Innovativeness refers to engaging in and supporting new ideas. Thus, innovative companies are able to develop new products and processes, which they can turn into increased performance (Kellermanns et al. 2012a; Bergfeld and Weber 2011). Proactiveness helps companies to anticipate market needs and to reap benefits from being first in the market (De Massis et al. 2014; Nordqvist and Melin 2010). Thus, we hypothesize:

H1a

A family firm’s Innovativeness and its financial performance are positively related.

H1b

A family firm’s Proactiveness and its financial performance are positively related.

The degree of Risk-Taking in family firms and its effect on performance is discussed more divergently. This attitude is often considered to be less prevailing with family firms (Lumpkin et al. 2010; Nordqvist and Melin 2010; Short et al. 2009; Nordqvist et al. 2008) as safety thinking (performance hazard risk) and keeping the firm control within the family (control risk) are assumed to be superior goals (Zellweger and Sieger 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007; Hiebl 2013). However, undiversified wealth of the managers’ own capital (ownership risk) habitually is invested in the company, leading to a risk-bearing and risk-sharing attitude (Zahra 2003) and indicating a relatively high level of Risk-Taking (Xiao et al. 2001; Zellweger and Sieger 2012; Bianco et al. 2013). Previous literature disagrees on the amplitude of entrepreneurial Risk-Taking of family firms. While Zahra (2005) states that Risk-Taking is important for the survival of a family business, Naldi et al. (2007) show that family firms are more risk averse than non-family firms and that Risk-Taking has a negative impact on financial performance due to superior goals such as safety thinking and keeping firm control within the family. We hypothesize a negative effect of risk-taking which is in accordance with the majority of prior literature (Hiebl 2013):

H1c

A family firm’s Risk-Taking and its financial performance are negatively related.

Similar to the findings for Innovativeness and Proactiveness, literature largely agrees on the direct positive performance effect of having a propensity to act autonomously (Lumpkin and Dess 2001; Lumpkin et al. 2009).The dimension Autonomy refers to acting independently and making key decisions without external influence. Autonomy is important because entrepreneurial action leads to departing from existing knowledge and routines which can turn into organizational constraints (Habbershon and Pistrui 2002; Zellweger and Sieger 2012). Thus, autonomy fosters performance by making an organization more flexible and agile. Consequently we hypothesize the following:

H1d

A family firm’s Autonomy and its financial performance are positively related.

The dimension Competitive Aggressiveness is often considered to be less applicable for family businesses (Lumpkin et al. 2010; Nordqvist and Melin 2010; Nordqvist et al. 2008) due to positive image and reputation goals. A tendency to be aggressive towards competitors can result in negative consequences from the industry and society such as disrespect and a bad reputation (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013). Family firms are influenced from their family-related social embeddedness and thus prefer to compete unaggressively (Le Breton-Miller et al. 2011). An aggressive attitude might result in long-term financial losses, due to the expected negative consequences from society and competition. Consequently and opposing to the generic entrepreneurship literature (Lumpkin and Dess 2001), we hypothesize for the family firm context:

H1e

A family firm’s Competitive Aggressiveness and its financial performance are negatively related.

2.4.2 Control mechanisms and the EO-performance relationship

In family firm management, agency problems of self-control, moral hazard and adverse selection alter individual preferences for the worse, resulting in a lack of discipline, diverging individual and firm goals, and a decrease in managers’ capabilities (Eisenhardt 1989; Le Breton-Miller et al. 2011). Control mechanisms were found to reduce agency behavior by aligning individual and firm preferences, consequently resulting in higher financial performance (Chrisman et al. 2007; Sieger et al. 2013; Helsen et al. 2016). We hypothesize in accordance with prior literature that the use of control mechanisms will avoid agency behavior by aligning individual and family (firm) preferences through specific monitoring and evaluation procedures (Sieger et al. 2013; Eisenhardt 1989). When agency behavior is prevented, individual attitudes towards Innovativeness, Proactiveness, Risk-Taking, Autonomy and Competitive Aggressiveness will align with the family firm attitudes towards these entrepreneurial behaviors. This systematic agency-avoiding control (Chrisman et al. 2007) will have a positive effect on the transformation of entrepreneurial behavior into financial performance along all five EO dimensions. We therefore hypothesize:

H2a

A family firm’s Innovativeness has a more positive effect on financial performance when control mechanisms are installed.

H2b

A family firm’s Proactiveness has a more positive effect on financial performance when control mechanisms are installed.

H2c

A family firm’s Risk-Taking has a less negative effect on financial performance when control mechanisms are installed.

H2d

A family firm’s Autonomy has a more positive effect on financial performance when control mechanisms are installed.

H2e

A family firm’s Competitive Aggressiveness has a less negative effect on financial performance when control mechanisms are installed.

2.4.3 Family-related goals and the EO-performance relationship

Family firms are characterized by multiple family norms, values and goals (Zellweger et al. 2013; Berrone et al. 2010). These include SEW elements such as strong family bonds, identification with and emotional attachment to the firm, social ties and the goal to pass on the firm to the next generation (Berrone et al. 2012). We argue that, in general, these shared SEW goals are relevant for the longevity and survival of the family business, but at the same time, strong SEW goals have a ‘dark side’ (Kellermanns et al. 2012b). This negative effect originates from the fact that SEW goals “may prevent the firm to reap the fruits of their entrepreneurial efforts” (Schepers et al. 2014, p. 39). For instance, strong family bonds might impede implementing the appropriate levels of Autonomy in decision-making or Risk-Taking when competing. Consequently, we expect that prioritizing these often non-financial goals leads to an inefficient use of entrepreneurial capacities, due to, for example, wealth-preserving or family-entrenched actions. Creating an alternative guideline for managing business behavior, we postulate in accordance with previous literature (Gnan et al. 2015) that optimizing the adherence of family managers to these goals can be used as tools to guide family firm management. We hypothesize that these goals guide the family firm management in such a way that the higher the level of non-financial SEW goals is, the more negative its impact on the multidimensional EO-performance relationship (see H1) will be due to inefficiencies in the exploitation of entrepreneurial capacities:

H3a

A family firm’s Innovativeness has a less positive effect on financial performance when family-related goals are strong.

H3b

A family firm’s Proactiveness has a less positive effect on financial performance when family-related goals are strong.

H3c

A family firm’s Risk Taking has a more negative effect on financial performance when family-related goals are strong.

H3d

A family firm’s Autonomy has a less positive effect on financial performance when family-related goals are strong.

H3e

A family firm’s Competitive Aggressiveness has a more negative effect on financial performance when family-related goals are strong.

3 Research design

3.1 Sample and procedure

This study utilized a quantitative research design to investigate the EO-performance relationship for the case of family firms. For this purpose, we conducted a survey with a large sample of family firms, as suggested by prior research (Nordqvist et al. 2008). We developed the questionnaire based on prior scales in literature. These scales were originally in English, but then translated into German through a translation and back-translation procedure by either established translations from literature (for the EO construct) or, if not available, through translations by two university academics. The questionnaire was pre-tested by six academics and two family executives from family firms. The comments of these academics and executives on content, structure, wording and scaling were taken into account during the revision of the final version of the survey.

An email link to an online questionnaire was sent out in June 2014 to a sample of 1056 family firms in the three provinces Vorarlberg, Tyrol, Salzburg of Western Austria. This geographic area was chosen because it displays a relatively homogeneous context with regards to population, income and infrastructure. In Austria, roughly 90% of all companies are family firms (Haushofer 2013). Excluding the number of one-person enterprises, still 54% of all businesses are family firms. 1.7 million people (67% of all workforce) are employed in these mostly small businesses (<10 employees). The majority of family firms are active in the tourism, construction and manufacturing industries.

The questionnaire was addressed to family firm managers, while the sample was created through online research of family firms in Western Austria. Two email reminders were sent out after four and eight weeks respectively and one phone call was conducted after 12 weeks to complete the data collection in September 2014. In total, the online survey resulted in 180 returned questionnaires filled out by family firm managers. Despite all necessary care during the sample selection, it proved difficult to determine the ownership situation and thus pre-select family businesses meeting the proposed definition. Therefore, to make sure that the targeted companies met our definition of family firms, introductory defining questions were posed. These questions included the alignment of ownership and management in the same family/-ies, a majority of shares held by the family/-ies, and at least two family members being active in the firm (Miller et al. 2007; Westhead and Cowling 1998; Steiger et al. 2015; O’Boyle et al. 2012). We assume that the introductory defining questions yielded a high rate of uncompleted questionnaires as, for example, the ownership situation did not confirm with our requirement. There are several other potential reasons for the relatively large number of non-completed questionnaires: First, the email link in several cases had to be sent to a general email address of the firm due to unavailability of personalized addresses. Therefore, the link in these emails supposedly was clicked before forwarding it to a family firm manager, which also added to the total number of returned questionnaires. Second, the questionnaire was relatively extensive (e.g. the semantic differentials for 17 items of the EO dimensions), and thus may have caused some respondents to terminate the survey before completion. Third, the dropout rate may be related to several confidential questions such as those on financial performance or personal questions related to family and emotions (e.g. in the SEW items). Overall, this drop in numbers was expected and aimed to be offset by the quality and reliability of the data retrieved. The final number of 180 completed questionnaires is comparable to other studies building on primary data collection in the fields of entrepreneurship and family business research (e.g. Songini and Gnan 2015; Zellweger et al. 2012). The final return rate of 17.1% is well above the average of 10 to 12% response rates of prior studies (e.g. Sieger et al. 2013). Table 1 describes the sample of our research.

3.2 Measurement

3.2.1 Entrepreneurial orientation

The scales to evaluate the EO dimensions (see Table 2) were measured on a seven-point semantic differential of two opposed statements, which are based on prior literature (Covin and Slevin 1989; Lumpkin and Dess 2001; Lumpkin et al. 2009; Hughes and Morgan 2007). The dimension Competitive Aggressiveness was measured with an additional item (C4; Kallmuenzer and Peters 2017), which aimed at capturing “aspects of the subconstructs that were not included in the previously used scales” (Lumpkin and Dess 2001, p. 439). This additional item measures the attitude of family firms in competition and addresses previous discussions on the less aggressive competitive behavior of family firms (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz 2013; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). To assure content validity, the accuracy and importance of this item has also been discussed and agreed upon with the pre-testing experts (Churchill 1979). Overall, five EO dimensions were measured with 17 items.

We conducted factor analyses to extract the respective dimensions of the multidimensional EO construct (Homburg and Giering 1996). These factor analyses confirmed all three items of Innovativeness (I1 to I3; Covin and Slevin 1989), Proactiveness (P1 to P3; Covin and Slevin 1989; Lumpkin and Dess 2001), and Risk-Taking (R1 to R3; Covin and Slevin 1989). For Autonomy (A1 to A3; Lumpkin et al. 2009) three out of four items were confirmed, while for Competitive Aggressiveness (C3 and C4; Lumpkin and Dess 2001; Kallmuenzer and Peters 2017; Hughes and Morgan 2007) two out of four items were confirmed. The newly added item (Kallmuenzer and Peters 2017) proved to be helpful to retain this EO dimension for further analysis. The factor loadings and Cronbach’s Alpha reached satisfying levels for Innovativeness (factor loadings ranging from .75 to .85; α = .72), Proactiveness (factor loadings ranging from .73 to .85; α = .70), Risk-Taking (factor loadings ranging from .85 to .88; α = .84), Autonomy (factor loadings ranging from .66 to .87; α = .64) and Competitive Aggressiveness (factor loading .86; α = .63). These results are comparable to previous family business research on EO (Naldi et al. 2007; Casillas et al. 2010).

3.2.2 Control mechanisms

Control mechanisms were measured with a scale that aims at measuring the presence of agency costs in family business (Sieger et al. 2013; Chrisman et al. 2007). The scale is a result of the assumption that “monitoring, while costly, reduces agency behavior” (Sieger et al. 2013, p. 3) and was measured with four items on a five-point Likert Scale from “never” (=1) to “very often” (=5) (Chrisman et al. 2007). As the scale was originally exclusively used for addressing the CEO of a firm, the wording of the fourth item had to be slightly adapted to also suit other family managers (“To assess the performance of the CEO, input from other managers and subordinates is used”), but deleted due to a low factor loading. The other three items (“In our company there is personal, direct observation”; “In our company, short-term performance is evaluated regularly”; “In our company, progress regarding long-term goals is evaluated regularly”) loaded highly on one factor (ranging from .73 to .85), displaying a Cronbach’s Alpha of .74.

3.2.3 Family-related goals

To measure family-related goals, we applied the unidimensional FIBER scale for the SEW construct by Berrone et al. (2012). This scale is based on the SEW concept and covers family-related firm goals (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). Based on several scales from prior research, Berrone et al. (2012) proposed a total of potential 30 items measuring the five FIBER dimensions (Family control and influence; Identification of family members with the firm; Binding social ties; Emotional attachment of family members; Renewal of family bonds through dynastic successions). The inclusion of all 30 items was considered too much because the questionnaire was already quite extensive. Thus, we selected twelve items measuring the five dimensions for the present study depending on the expected fit of the items. The selection of items was also discussed during the pretest. The items were measured along a seven-point Likert Scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (=1) to “strongly agree” (=7). As this construct has not been sufficiently tested in research, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation to extract uncorrelated components for the FIBER construct and to determine whether the dimensions represented distinct dimensions. Table 3 shows that this analysis created three components, as all three items of Family control and influence (items F1 to F3) and Identification of family members with the firm (items I1 to I3) loaded for the same factor (α = .86), and all items for Binding social ties (In my family business, contractual relationships are mainly based on trust and norms of reciprocity; Contracts with suppliers are based on enduring long-term relationships in my family business) had to be dropped as they did not pass the necessary factor loadings (>.6) for any of the factors or showed high cross-loadings. The two items of Emotional attachment of family members (items E1 and E2; α = .75) and Renewal of family bonds through dynastic successions (items R1 and R2; α = .84) formed separate factors. For further analysis, we measured SEW as a second-order construct by reducing the three factors from the factor analysis to one variable for SEW. The three factors loaded on the same factor with a Cronbach’s Alpha of α = .60, which can be considered acceptable for a relatively untested construct (Naldi et al. 2007; Casillas et al. 2010).

3.2.4 Financial performance

For measuring financial performance, the four measures Sales Growth, Return on Sales, Gross Profit, and Net Profit of Lumpkin and Dess (2001) and the two measures Return on Equity and Return on Investment of Becker (2005) were applied. Respondents were asked how these variables developed over the last three years relative to their competitors, which was measured on a seven-point Likert Scale from “low performer” (=1) to “high performer” (=7). Previous research using survey data has demonstrated the reliability of such measures (Lumpkin and Dess 2001). The performance measure demonstrated very good reliability and validity (factor loadings ranging from .80 to .95; α = .96).

3.2.5 Control variables

For assessing other potential influences on the dependent variable, we implemented several control variables (Bryman and Cramer 2005). This is important as firm performance could also be explained by other influencing factors besides the proposed relationships. Thus, we implemented dummy variables for the industries, in order to control for industry specific performance effects (Schepers et al. 2014). Prior research also indicated potential influences of firms size on company outcomes (Kellermanns et al. 2012a; Beck et al. 2011). We therefore controlled for the number of employees as proxy for firm size. Family business literature (Beck et al. 2011; Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2011) has shown that the generational stage influences family firm outcomes. We therefore controlled by implementing a dummy variable if the first generation was still in charge of the company. Finally, the results might differ if non-family members are actively involved in managing the business and if the company is run by a family member (Anderson and Reeb 2003; Jaskiewicz and Klein 2007; George et al. 2005). Thus, we included a variable for the involvement of non-family members in management and a dummy variable for the case that the CEO was a member of the owning family.

4 Results

In our sample, we used self-reported data to assess the dependent and independent variables at the same time and from the same key informant. Thus, there is a potential source for common method bias in our data (Podsakoff et al. 2003). To control for this bias and to improve internal validity, we reversed some items in the questionnaire and separated several variables and items to eliminate proximity effects (Podsakoff et al. 2012). In addition, we conducted a Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ 1986). In this single-factor test, all items are subject to an exploratory factor analysis. Common method variance can be assumed if (1) a single factor emerges from an unrotated factor solution, or (2) the first factor explains the majority of the variance in the variables (Podsakoff and Organ 1986). This analysis produced 13 factors (explaining 73.28% of the variance), with the first factor explaining 19.39% of the variance. As no single factor emerged, and as the first factor did not explain the majority of the variance, common method variance was not found to be a major issue. To test for non-response bias and to improve external validity, the 20% first and 20% last respondents were compared via an ANOVA, as late respondents (those only replying to the reminders) are more similar to non-respondents (Armstrong and Overton 1977). We found no significant differences.

Table 4 presents the latent variable correlations together with the means and standard deviations. Most correlations among our constructs are rather low and below the recommended threshold of .65 (Tabachnick and Fidell 2012). In addition, the variance inflation factors of the variables (1.05–5.28) were all well below the threshold of 10 as recommended in literature (O’brien 2007). We therefore conclude that multicollinearity is not a serious concern for our data.

We tested the proposed hypotheses applying hierarchical OLS regressions. Tables 5 and 6 report the results of this analysis. The effects from the five EO dimensions in family firms on financial performance were hypothesized to be moderated by control mechanisms (Table 5), and family-related goals, respectively (Table 6). In both cases of the regression analysis, the variables were mean centered to reduce multicollinearity concerns (Aiken and West 1991).

In the first model only the control variables were considered. In the second model the direct effects of the five EO dimensions, i.e. Innovativeness, Proactiveness, Risk-Taking, Autonomy and Competitive Aggressiveness, on the dependent variable, were incorporated. In the third model the direct effect of the respective moderating factors on the dependent variable were added. Finally, in the fourth model the interaction effects between the respective moderating factors and the five EO dimensions were included.

For the regression analysis with control mechanisms as the moderating variable (Table 5), the first model with the control variables yields an adjusted R2 value of −.018 (F = .74; p > .1), in which only the influence of the handcraft industry (β = .22; p < .1) is significant. The family firm specific control variables (1) generation (comparing firms in their first vs. later generations); (2) non-family managers (number of non-family managers involved); and (3) family CEO (comparing firms with a family CEO to those with a non-family CEO) did not have significant effects on performance. The second model for the direct effect of the EO dimensions on financial performance (hypothesis H1) gives a final adjusted R2 value of .13 (F = 2.55; p < .01). Results for the five dimensions show that Proactiveness (β = .22; p < .05) and Autonomy (β = .15; p < .1) are significant and thus, hypotheses H1b and H1d are supported. The remaining independent variables do not show significant direct influences on financial performance and thus H1a, H1c and H1e are not supported.

The third model (adjusted R2 = .15; F = 2.71; p < .01) shows a significant and positive direct effect of control mechanisms on financial performance (β = .16; p < .05). The fourth model investigates the interaction effects between each of the five EO dimensions and control mechanisms. This final model yields an adjusted R2 value of .21 (F = 3.06; p < .01). Results show that two interaction effects are significant: the interactions between control mechanisms and Innovativeness (β = −.38; p < .01) and control mechanisms and Autonomy (β = .30; p < .001). Thus, hypothesis H2a cannot be supported, because the negative impact of control mechanisms on the effect of Innovativeness on financial performance is opposed to the hypothesized effect. Hypothesis H2d is supported, while the other hypotheses (H2b, H2c and H2e) are not supported due to insignificant effects.

For the regression analysis with family-related goals as the moderating variable (Table 6), the results for model 1 and 2 concur with the results from the regression analysis with formal control mechanisms as the moderating variable. The third model (adjusted R2 = .13; F = 2.53; p < .01) for the direct effect of family-related goals shows no significant effect (β = .10; p > .1). The fourth model (adjusted R2 = .15; F = 2.38; p < .01) investigates the interaction effects between each of the five EO dimensions and family-related goals. Results show that one interaction is significant: the interaction between family-related goals and Risk-Taking (β = −.20; p < .05) for financial performance as the dependent variable. Thus, hypothesis H3c is supported. Hypotheses H3a, H3b, H3d and H3e are not supported.

Due to the fact that moderating variables may take multiple values, we plotted the significant interactions from the regression analyses to ease the interpretation of these interaction effects.

Figure 1 indicates that in family firms with a low intensity of control mechanisms an increase in Innovativeness can be transferred into a higher financial performance. In this situation, a low intensity of control mechanisms boosts the effect of Innovativeness on financial performance. In contrast, when family firms score low in Innovativeness, a higher financial performance is achieved when intensity of control mechanisms is high compared to low. At the same time, highly innovative family firms merely show a slightly better financial performance when intensity of control mechanisms is low compared to high.

An increased Autonomy can be transferred into a higher financial performance (Fig. 2) in family firms with a high intensity of control mechanisms. In this situation, control mechanisms enhance the positive effect of Autonomy on financial performance. When a low intensity of control mechanisms is in place, increased Autonomy reduces the financial performance of the family firm. Overall, when Autonomy is low, a low intensity of control system usage (as compared to high) merely triggers a marginally better financial performance. Comparing the financial performance of family firms with high Autonomy shows that a high intensity of control mechanisms (as compared to low) yields a higher financial performance.

Figure 3 shows that in family firms with a low degree of family-related goals the effect of Risk-Taking on financial performance is more intense. In this case, family-related goals mitigate the positive effect of Risk-Taking on financial performance. Furthermore, the plot shows that in family firms with low Risk-Taking a high degree of family-related goals (as compared to low) yields a higher financial performance. In turn, the difference in terms of financial performance is marginally for high Risk-Taking family firms. High Risk-Taking family firms merely show a slightly better financial performance when family-related goals are low (as compared to low).

5 Discussion

All five EO dimensions could be identified in the factor analysis and retained for family firms. However, the regression analysis for the effect of the EO dimensions on financial performance in family firms revealed that only two dimensions directly impact financial performance. Thus, all but hypothesis H1b and H1d had to be rejected. Significant effects were identified for the impacts of Proactiveness and Autonomy on financial performance. The effect of Proactiveness shows that it is also necessary for family firms to initiate actions, which competitors then respond to, to be the first business to introduce new products or services, and to be ahead of other competitors in introducing novel ideas or products. The effect of Autonomy shows that also family firms perform superior in terms of financial performance when being able to act autonomously, without being restricted by stakeholder interests. In addition, these results for the direct effects can be interpreted as a confirmation of the multidimensionality of the EO-construct (Lumpkin and Dess 1996), which states that not all EO dimensions have to be present for an entrepreneurial attitude to exist. Furthermore, results show that entrepreneurial attitudes and their effect on performance are highly complex phenomena in family firms. Thus, contextual factors affecting the influence of entrepreneurial attitudes in family firms are a necessary field of investigation. Two promising context factors of entrepreneurial behavior in family firms are discussed in the following: management control mechanisms and family-related goals.

Prior literature in management accounting already showed that family dynamics such as trust (Sundaramurthy 2008) lead to a reduction in information asymmetries (Senftlechner and Hiebl 2015) and therefore require more complex control and management initiatives (Helsen et al. 2016). Our study demonstrates that in family firms the impact of particular EO dimensions on firm performance depends on the usage of control mechanisms and the adherence to family-related goals. While financial performance is also directly and positively influenced by the usage of control mechanisms, family-related goals do not influence financial performance per se. The test of interaction effects between the EO dimensions and the usage of control mechanisms as well as the adherence to family-related goals showed both hypothesized and counterintuitive results.

First, Innovativeness is found to have a less positive effect on financial performance when control mechanisms are installed. This result is opposed to hypothesis H2a. We expected control mechanisms to intensify the efficiency of Innovativeness. The findings, however, show that less monitoring enhances the effect of Innovativeness on financial performance. Only in firms with low Innovativeness employing control mechanisms showed to be positive in terms of performance. Ostensibly, it needs different mechanisms to control innovation (Davila et al. 2009), particularly in highly innovative firms (Covin et al. 2016), and controlling the firm too much will hamper efficient innovative processes and exploitation (Bergfeld and Weber 2011; Gschwantner and Hiebl 2016). This complexity of finding appropriate control mechanisms could stem from the fact that innovation is associated with learning mechanisms involving exploration, experimentation and play. In addition, the outcomes of such innovation processes are of high risk (March 1991) so that control mechanisms on the one hand could impede explorative learning through controls not allowing experimentation and on the other hand could sanction risk associated to this kind of learning. Overall, the ability to reach higher levels of ambidexterity may become especially relevant for family firms, as such firms often show higher reliance on cultural and informal controls (Calabrò and Mussolino 2013).

Second, the results for the interaction effect between Autonomy and control mechanisms show that in-house monitoring mechanisms offer guidance and help in organizing a “structured autonomy” (Lumpkin et al. 2009, p. 50), as they enhance the effect of Autonomy on financial performance (confirming H2d), particularly in firms that show high Autonomy. Autonomous firms in uncontrolled agency situations have significantly lower financial performance. We conclude that the efficiency of an autonomous orientation is intensified when family firm managers are being monitored, presumably due to the incentive or pressure to perform in cohesion with family firm interests. Stated boldly, autonomy needs guidelines in order not to lose ground.

Third, results illustrate that the effect of Risk-Taking on performance is hampered (confirming H3c) when family-related goals are of high priority (Cruz and Nordqvist 2012), particularly in firms showing high levels of Risk-Taking. Managing these goals refers to the adherence of family managers to SEW and thus rather non-financial (Zellweger et al. 2013) firm goals, which secure the survival and longevity of the family firm. For these reasons, capabilities to take risks in business opportunities might not be used to the full extent (Schepers et al. 2014), leading to potential financial performance losses. Drawing on the results of this study, we conclude that the degree of family managers’ adherence to SEW goals needs to be particularly managed for the effect of Risk-Taking on financial performance. While SEW elements are relevant goals from a family perspective and thus need to be considered, it is still necessary to manage the trade-off between an appropriate level of adherence to these goals and an effective use of Risk-Taking capabilities to be able to achieve financial performance .

Summarizing, the results show that control mechanisms and adherence to family-related goals are viable means to optimize the transmission of the EO-performance link for the family firm context. The findings also point out that these tools can be used to direct entrepreneurial attitudes to an efficient use, exploiting the available EO capabilities. Overall, we believe that these findings contribute to a better understanding of how family-related elements merge with general management behavior in family firms (Kraus et al. 2012a; Zellweger and Sieger 2012).

6 Conclusion

This study showed that entrepreneurial attitudes are also present in family firms and relevant for financial performance. While proactive and autonomous behavior directly contribute to family business performance, control mechanisms enable family firms to further reap the benefits of Autonomy in terms of financial performance, but undermine the financial outcomes from Innovativeness. Furthermore, a high focus on family-related goals negatively influences the effect of Risk-Taking on financial performance.

The study is not without limitations. With regards to our sample it has to be considered that almost half of the respondents (45.6%) were family firms from the tourism and hospitality industry and about two thirds (68.9%) were small businesses (<50 employees). However, Western Austria is characterized by a tourism and leisure industry, which in turn is dominated by small family firms and thus represents the context of this study (Getz and Carlsen 2000). Nonetheless, our sample might be affected from peculiarities from this industry and culture. As a consequence, the results might not be exactly replicable when conducting such research elsewhere. Furthermore, even though the agency and SEW perspectives offered numerous insights into the EO-performance relations, it can only explain certain effects. Shedding more light on the subject from other relevant perspectives such as the resource-based view of the family firm (Habbershon and Williams 1999) to the analysis of the phenomenon might further complete our knowledge about entrepreneurial attitudes in family firms. Finally, our study was limited to a single respondent survey design. While this procedure makes sense in terms of feasibility and we have taken measures to mitigate and test for potential bias, we cannot entirely exclude them. However, these limitations provide fertile research opportunities for future research initiatives. In terms of robustness of the results, we want to encourage studies to replicate the proposed relationships while accessing different data sources.

Additionally, for future research we suggest to further deepen the investigation of entrepreneurial attitudes in a family firm context. We believe that it is particularly necessary to identify more drivers of family firm specific EO (Zellweger et al. 2012), to be able to use and exploit them more efficiently. The results of this study have shown that family dynamics play an important role for family business behavior. We believe that a stronger focus on the heterogeneity of family firms in future research would help to better differentiate and understand relevant entrepreneurial attitudes, goals and governance structures in family firms (Schulze et al. 2001; Nordqvist et al. 2014). Family firms in different life cycle stages, for example (De Massis et al. 2014), supposedly have different entrepreneurial attitudes and goals. Furthermore, the role of control mechanisms and its interrelations with innovation processes needs further analysis as innovation and control types differ amongst family firms (see Davila et al. 2009, p. 299). We recommend applying longitudinal or case studies to better grasp issues of transgenerational entrepreneurship or interactions between management control systems and business strategies (Langfield-Smith 1997). We also hope to have paved the way for further research on the importance and measurement of non-financial goals of family firms. Referring to previous calls in literature, non-financial performance components might have to be considered for grasping the case of family firms more deeply (Zellweger et al. 2013).

Practical implications for family firms are manifold. Findings show that control mechanisms need to be employed carefully to provide managers enough freedom in innovation processes (low levels of control) and to align autonomous mannerism with the interests of the family, at the same time (high levels of control). Entrepreneurial processes require space for creativity, a high degree of discretion (Galbraith 2004), but also thorough guidance. One way to control and still provide space for creative innovation goes back to the ‘stage-gate model’ by Cooper (1990) that allows managers to innovate freely and only be controlled when switching to new ‘gates’. To guide Autonomy, we follow the recommendations of prior family business research (Lane et al. 2006) that suggest to guide Autonomy in family firms through explicit, written guidelines (Mazzola et al. 2008). In addition, our findings indicate that adherence to family-related, often non-financial goals can lead to an unhealthy level of Risk-Taking. Family firm managers may tend to sometimes loose perspective for business orientation due to the relevance of familial relations and succession goals (Jaskiewicz et al. 2013; Abdalla et al. 1998). One option to address this sometimes nepotistic behavior (Tokarczyk et al. 2007) could be the initiation of intergenerational rounds of discussion and knowledge exchange, reinforcing and sharing a common understanding of decisive firm resources (Cabrera-Suarez et al. 2001). This discussion can also be fruitful by explicitly discussing family members’ SEW goals and how to balance Risk-Taking and SEW goals within their available degree of independence in the business (Antoncic and Hisrich 2003). Finally, we suggest to family firm management and consultants alike to re-focus on and exploit firms’ entrepreneurial orientation capabilities to leverage financial performance, while maintaining competitive advantages from family resources.

References

Abdalla HF, Maghrabi AS, Raggad BG (1998) Assessing the perceptions of human resource managers toward nepotism. Int J Manpow 19(8):554–570. doi:10.1108/01437729810242235

Abernethy MA, Chua WF (1996) A field study of control system “Redesign”: the impact of institutional processes on strategic choice. Contemp Acc Res 13(2):569–606. doi:10.1111/j.1911-3846.1996.tb00515.x

Aiken LS, West SG (1991) Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage, Newbury Park

Anderson RC, Reeb DM (2003) Founding-family ownership and firm performance: evidence from the S&P 500. J Financ 58(3):1301–1327. doi:10.1111/1540-6261.00567

Antoncic B, Hisrich RD (2003) Clarifying the intrapreneurship concept. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 10(1):7–24. doi:10.1108/14626000310461187

Armstrong JS, Overton TS (1977) Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J Mark Res 14(3):396–402. doi:10.2307/3150783

Beck L, Janssens W, Debruyne M, Lommelen T (2011) A study of the relationships between generation, market orientation, and innovation in family firms. Fam Bus Rev 24(3):252–272. doi:10.1177/0894486511409210

Becker DR (2005) Ressourcen-Fit bei M&A-Transaktionen: Konzeptionalisierung, Operationalisierung und Erfolgswirkung auf Basis des resource-based view. Deutscher Universitätsverlag

Bergfeld M-MH, Weber F-M (2011) Dynasties of innovation: highly performing German family firms and the owners’ role for innovation. Int J Entrep Innov Manag 13(1):80–94. doi:10.1504/IJEIM.2011.038449

Berrone P, Cruz C, Gómez-Mejía LR, Larraza-Kintana M (2010) Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: do family-controlled firms pollute less? Adm Sci Q 55(1):82–113. doi:10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.82

Berrone P, Cruz C, Gómez-Mejía LR (2012) Socioemotional wealth in family firms: theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Fam Bus Rev 25(3):258–279. doi:10.1177/0894486511435355

Bianco M, Bontempi ME, Golinelli R, Parigi G (2013) Family firms’ investments, uncertainty and opacity. Small Bus Econ 40(4):1035–1058. doi:10.1007/s11187-012-9414-3

Bouncken RB, Pesch R, Kraus S (2015) SME innovativeness in buyer–seller alliances: effects of entry timing strategies and inter-organizational learning. RMS 9(2):361–384. doi:10.1007/s11846-014-0160-6

Bouncken RB, Plüschke BD, Pesch R, Kraus S (2016) Entrepreneurial orientation in vertical alliances: joint product innovation and learning from allies. Rev Manag Sci 10(2):381–409. doi:10.1007/s11846-014-0150-8

Bryman A, Cramer D (2005) Quantitative data analysis with SPSS release 12 and 13: a guide for social scientists. Routledge, London

Cabrera-Suarez K, Saa-Perez P, Garcia-Almeida D (2001) The succession process from a resource- and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Fam Bus Rev 14(1):37–48. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2001.00037.x

Calabrò A, Mussolino D (2013) How do boards of directors contribute to family SME export intensity? The role of formal and informal governance mechanisms. J Manag Gov 17(2):363–403. doi:10.1007/s10997-011-9180-7

Casillas JC, Moreno AM (2010) The relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and growth: The moderating role of family involvement. Entrep Reg Dev 22(3–4):265–291

Casillas JC, Moreno AM, Barbero JL (2010) A configurational approach of the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and growth of family firms. Fam Bus Rev 23(1):27–44. doi:10.1177/0894486509345159

Cesinger B, Hughes M, Mensching H, Bouncken R, Fredrich V, Kraus S (2016) A socioemotional wealth perspective on how collaboration intensity, trust, and international market knowledge affect family firms’ multinationality. J World Bus 51(4):586–599. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2016.02.004

Chrisman JJ, Chua JH, Kellermanns FW, Chang EP (2007) Are family managers agents or stewards? An exploratory study in privately held family firms. Fam Influ Firms 60(10):1030–1038. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.12.011

Chua JH, Chrisman JJ, Sharma P (1999) Defining the family business by behavior. Entrep Theory Pract 23(4):19–39

Churchill GA (1979) A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J Mark Res 16(1):64–73. doi:10.2307/3150876

Cooper RG (1990) Stage-gate systems: a new tool for managing new products. Bus Horiz 33(3):44–54. doi:10.1016/0007-6813(90)90040-I

Covin JG, Slevin DP (1989) Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strat Mgmt J 10(1):75–87. doi:10.1002/smj.4250100107

Covin JG, Eggers F, Kraus S, Cheng C-F, Chang M-L (2016) Marketing-related resources and radical innovativeness in family and non-family firms: a configurational approach. J Bus Res. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.03.069

Cruz C, Nordqvist M (2012) Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: a generational perspective. Small Bus Econ 38(1):33–49. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9265-8

Davila A, Foster G, Oyon D (2009) Accounting and control, entrepreneurship and innovation: venturing into new research opportunities. Eur Acc Rev 18(2):281–311. doi:10.1080/09638180902731455

De Massis A, Chirico F, Kotlar J, Naldi L (2014) The temporal evolution of Proactiveness in family firms: the horizontal S-curve hypothesis. Fam Bus Rev 27(1):35–50. doi:10.1177/0894486513506114

Deephouse DL, Jaskiewicz P (2013) Do family firms have better reputations than non-family firms? An integration of socioemotional wealth and social identity theories. J Manag Stud 50(3):337–360. doi:10.1111/joms.12015

Eddleston KA, Kellermanns FW, Zellweger TM (2010) Exploring the entrepreneurial behavior of family firms: does the stewardship perspective explain differences? Entrep Theory Pract 36(2):347–367. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00402.x

Eisenhardt KM (1989) Agency theory: an assessment and review. Acad Manag Rev 14(1):57–74. doi:10.2307/258191

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983) Agency problems and residual claims. J Law Econ 26(2):327–349. doi:10.2307/725105

Galbraith JR (2004) Designing the innovating organization. CEO Publication, p 202

George G, Wiklund J, Zahra S (2005) Ownership and the internationalization of small firms. J Manag 31(2):210–233. doi:10.1177/0149206304271760

Getz D, Carlsen J (2000) Characteristics and goals of family and owner-operated businesses in the rural tourism and hospitality sectors. Tour Manag 21(6):547–560. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00004-2

Gnan L, Montemerlo D, Huse M (2015) Governance systems in family SMEs: the substitution effects between family councils and corporate governance mechanisms. J Small Bus Manag 53(2):355–381. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12070

Gómez-Mejía LR, Haynes KT, Núñez-Nickel M, Jacobson KJ, Moyano-Fuentes J (2007) Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Adm Sci Q 52(1):106–137. doi:10.2189/asqu.52.1.106

Gschwantner S, Hiebl MRW (2016) Management control systems and organizational ambidexterity. J Manag Control 27(4):371–404

Habbershon TG, Pistrui J (2002) Enterprising families domain: family-influenced ownership groups in pursuit of transgenerational wealth. Fam Bus Rev 15(3):223–237. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2002.00223.x

Habbershon TG, Williams ML (1999) A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Fam Bus Rev 12(1):1–25. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.1999.00001.x

Haushofer C (2013) Familienunternehmen in Österreich. Wirtschaftskammer Tirol, Innsbruck

Helsen Z, Lybaert N, Steijvers T, Orens R, Dekker J (2016) Management control systems in family firms: a review of the literature and directions for the future. J Econ Surv (forthcoming). doi:10.1111/joes.12154

Hiebl MR (2013) Risk aversion in family firms: what do we really know? J Risk Financ 14(1):49–70. doi:10.1108/15265941311288103

Homburg C, Giering A (1996) Konzeptualisierung und Operationalisierung komplexer Konstrukte. Marketing: Zeitschrift für Forschung und. Praxis 18(1):5–24

Hughes M, Morgan RE (2007) Deconstructing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance at the embryonic stage of firm growth. Ind Mark Manag 36(5):651–661. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2006.04.003

Jaskiewicz P, Klein S (2007) The impact of goal alignment on board composition and board size in family businesses. J Bus Res 60(10):1080–1089. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.12.015

Jaskiewicz P, Uhlenbruck K, Balkin DB, Reay T (2013) Is nepotism good or bad? Types of nepotism and implications for knowledge management. Fam Bus Rev 26(2):121–139. doi:10.1177/0894486512470841

Jaskiewicz P, Combs JG, Rau SB (2015) Entrepreneurial legacy: Toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. J Bus Ventur 30(1):29–49. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.001

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3(4):305–360. doi:10.2139/ssrn.94043

Kallmuenzer A (2015) The divergent transmission of entrepreneurial orientation in family business research. Int J Entrep Ventur 8(4):378–399. doi:10.1504/IJEV.2016.10001851

Kallmuenzer A, Peters M (2017) Exploring entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: the relevance of social embeddedness in competition. Int J Entrep Small Bus 30(2):191–213. doi:10.1504/IJESB.2017.081436

Kellermanns FW, Eddleston KA, Sarathy R, Murphy F (2012a) Innovativeness in family firms: a family influence perspective. Small Bus Econ 38(1):85–101. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9268-5

Kellermanns FW, Eddleston KA, Zellweger TM (2012b) Extending the socioemotional wealth perspective: a look at the dark side. Entrep Theory Pract 36(6):1175–1182. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00544.x

Kraus S, Craig JB, Dibrell C, Märk S (2012a) Family firms and entrepreneurship: contradiction or synonym? J Small Bus Entrep 25(2):135–139. doi:10.1080/08276331.2012.10593564

Kraus S, Pohjola M, Koponen A (2012b) Innovation in family firms: an empirical analysis linking organizational and managerial innovation to corporate success. RMS 6(3):265–286. doi:10.1007/s11846-011-0065-6

Kraus S, Rigtering JPC, Hughes M, Hosman V (2012c) Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: a quantitative study from the Netherlands. RMS 6(2):161–182. doi:10.1007/s11846-011-0062-9

Lane S, Astrachan J, Keyt A, McMillan K (2006) Guidelines for family business boards of directors. Fam Bus Rev 19(2):147–167. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00052.x

Langfield-Smith K (1997) Management control systems and strategy: a critical review. Acc Organ Soc 22(2):207–232. doi:10.1016/S0361-3682(95)00040-2

Le Breton-Miller I, Miller D, Lester RH (2011) Stewardship or agency? A social embeddedness reconciliation of conduct and performance in public family businesses. Organ Sci 22(3):704–721. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0541

Lumpkin GT, Dess GG (1996) Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad Manag Rev 21(1):135–172. doi:10.5465/AMR.1996.9602161568

Lumpkin GT, Dess GG (2001) Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance. J Bus Ventur 16(5):429–451. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00048-3

Lumpkin GT, Cogliser CC, Schneider DR (2009) Understanding and measuring autonomy: an entrepreneurial orientation perspective. Entrep Theory Pract 33(1):47–69. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00280.x

Lumpkin GT, Brigham KH, Moss TW (2010) Long-term orientation: implications for the entrepreneurial orientation and performance of family businesses. Entrep Reg Dev 22(3–4):241–264. doi:10.1080/08985621003726218

Malmi T, Brown DA (2008) Management control systems as a package—opportunities, challenges and research directions. Manag Acc Res 19(4):287–300. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2008.09.003

March JG (1991) Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ Sci 2(1):71–87. doi:10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

Martin WL, Lumpkin GT (2003) From entrepreneurial orientation to “family orientation”: generational differences in the management of family businesses. Paper presented at the 22nd babson college entrepreneurship research conference, Wellesley, MA, USA

Mazzola P, Marchisio G, Astrachan J (2008) Strategic planning in family business: a powerful developmental tool for the next generation. Fam Bus Rev 21(3):239–258. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2008.00126.x

Miller D (1983) The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag Sci 29(7):770–791. doi:10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770

Miller D, Le Breton-Miller I (2011) Governance, social identity, and entrepreneurial orientation in closely held public companies. Entrep Theory Pract 35(5):1051–1076. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00447.x

Miller D, Le Breton-Miller I, Lester RH, Cannella AA (2007) Are family firms really superior performers? J Corp Financ 13(5):829–858. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2007.03.004

Mitter C, Duller C, Feldbauer-Durstmüller B, Kraus S (2014) Internationalization of family firms: the effect of ownership and governance. RMS 8(1):1–28. doi:10.1007/s11846-012-0093-x

Mustakallio M, Autio E, Zahra SA (2002) Relational and contractual governance in family firms: effects on strategic decision making. Fam Bus Rev 15(3):205–222. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2002.00205.x

Naldi L, Nordqvist M, Sjöberg K, Wiklund J (2007) Entrepreneurial orientation, risk taking, and performance in family firms. Fam Bus Rev 20(1):33–47. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00082.x

Nordqvist M, Melin L (2010) Entrepreneurial families and family firms. Entrep Reg Dev 22(3/4):211–239. doi:10.1080/08985621003726119

Nordqvist M, Habbershon TG, Melin L (2008) Transgenerational entrepreneurship: exploring entrepreneurial orientation in family firms. In: Landström H, Smallbone D, Crijns H, Laveren E (eds) Entrepreneurship, sustainable growth and performance: frontiers in European entrepreneurship research. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 93–116

Nordqvist M, Sharma P, Chirico F (2014) Family firm heterogeneity and governance: a configuration approach. J Small Bus Manag 52(2):192–209. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12096

Nordqvist M, Melin L, Waldkirch M, Kumeto G (eds) (2015) Theoretical perspectives on family businesses. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

O’brien RM (2007) A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant 41(5):673–690. doi:10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6

O’Boyle EH, Pollack JM, Rutherford MW (2012) Exploring the relation between family involvement and firms’ financial performance: a meta-analysis of main and moderator effects. J Bus Ventur 27(1):1–18. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.09.002

Podsakoff PM, Organ DW (1986) Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manag 12(4):531–544. doi:10.1177/014920638601200408

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 63:539–569. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Poppo L, Zenger T (2002) Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements? Strateg Manag J 23(8):707–725. doi:10.1002/smj.249

Rigtering JC, Kraus S, Eggers F, Jensen SH (2013) A comparative analysis of the entrepreneurial orientation/growth relationship in service firms and manufacturing firms. Serv Ind J 34(4):275–294. doi:10.1080/02642069.2013.778978

Schepers J, Voordeckers W, Steijvers T, Laveren E (2014) The entrepreneurial orientation–performance relationship in private family firms: the moderating role of socioemotional wealth. Small Bus Econ 43(1):39–55. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9533-5

Schulze WS, Lubatkin MH, Dino RN, Buchholtz AK (2001) Agency relationships in family firms: theory and evidence. Organ Sci 12(2):99–116. doi:10.1287/orsc.12.2.99.10114

Schulze WS, Lubatkin MH, Dino RN (2003) Toward a theory of agency and altruism in family firms. J Bus Ventur 18(4):473–490. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00054-5

Schumpeter JA (1934) The theory of economic development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Sciascia S, Mazzola P, Chirico F (2013) Generational involvement in the top management team of family firms: exploring nonlinear effects on entrepreneurial orientation. Entrep Theory Pract 37(1):69–85. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00528.x

Senftlechner D, Hiebl MRW (2015) Management accounting and management control in family businesses. J Acc Org Change 11(4):573–606. doi:10.1108/JAOC-08-2013-0068

Short JC, Payne GT, Brigham KH, Lumpkin GT, Broberg JC (2009) Family firms and entrepreneurial orientation in publicly traded firms: a comparative analysis of the S&P 500. Fam Bus Rev 22(1):9–24. doi:10.1177/0894486508327823

Sieger P, Zellweger T, Aquino K (2013) Turning agents into psychological principals: aligning interests of non-owners through psychological ownership. J Manag Stud 50(3):361–388. doi:10.1111/joms.12017

Songini L, Gnan L (2015) Family involvement and agency cost control mechanisms in family small and medium-sized enterprises. J Small Bus Manage 53(3):748–779. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12085

Steiger T, Duller C, Hiebl MR (2015) No consensus in sight: an analysis of ten years of family business definitions in empirical research studies. J Enterp Cult 23(01):25–62. doi:10.1142/S0218495815500028

Sundaramurthy C (2008) Sustaining trust within family businesses. Fam Bus Rev 21(1):89–102

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2012) Using multivariate statistics, 6th edn. Pearson Education, Boston

Tokarczyk J, Hansen E, Green M, Down J (2007) A resource-based view and market orientation theory examination of the role of “Familiness” in family business success. Fam Bus Rev 20(1):17–31. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00081.x

Wales WJ (2016) Entrepreneurial orientation: a review and synthesis of promising research directions. Int Small Bus J 34(1):3–15. doi:10.1177/0266242615613840

Wales WJ, Gupta VK, Mousa F-T (2013) Empirical research on entrepreneurial orientation: an assessment and suggestions for future research. Int Small Bus J 31(4):357–383. doi:10.1177/0266242611418261

Westhead P, Cowling M (1998) Family firm research: the need for a methodological rethink. Entrep Theory Pract 23(1):31–56

Xi J, Kraus S, Filser M, Kellermanns FW (2013) Mapping the field of family business research: past trends and future directions. Int Entrep Manag J 11(1):113–132. doi:10.1007/s11365-013-0286-z

Xiao JJ, Alhabeeb MJ, Gong-Soog H, Haynes GW (2001) Attitude toward risk and risk-taking behavior of business-owning families. J Consum Aff 35(2):307–325

Zahra SA (2003) International expansion of U.S. manufacturing family businesses: the effect of ownership and involvement. J Bus Ventur 18(4):495–512. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00057-0

Zahra SA (2005) Entrepreneurial risk taking in family firms. Fam Bus Rev 18(1):23–40. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2005.00028.x

Zellweger T, Sieger P (2012) Entrepreneurial orientation in long-lived family firms. Small Bus Econ 38(1):67–84. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9267-6

Zellweger TM, Nason RS, Nordqvist M (2012) From longevity of firms to transgenerational entrepreneurship of families: introducing family entrepreneurial orientation. Fam Bus Rev 25(2):136–155. doi:10.1177/0894486511423531

Zellweger TM, Nason RS, Nordqvist M, Brush CG (2013) Why do family firms strive for nonfinancial goals? An organizational identity perspective. Entrep Theory Pract 37(2):229–248. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00466.x

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kallmuenzer, A., Strobl, A. & Peters, M. Tweaking the entrepreneurial orientation–performance relationship in family firms: the effect of control mechanisms and family-related goals. Rev Manag Sci 12, 855–883 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0231-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0231-6

Keywords

- Family dynamics

- Agency theory

- Control mechanism

- Socio-emotional wealth

- Entrepreneurial orientation

- Performance

- Quantitative