Abstract

Purpose

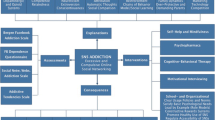

To describe (a) the conceptualization, purpose, and features of The American Cancer Society’s Cancer Survivors Network® (CSN; http://csn.cancer.org), (b) the ongoing two-phase evaluation process of CSN, and (c) the characteristics of CSN members.

Methods

An online opt-in self-report survey of CSN members (N = 4762) was conducted and digital metrics of site use were collected.

Results

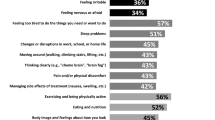

Annually, CSN attracts over 3.6 million unique users from over 200 countries/territories. Most commonly used site features are discussion boards (81.1%), the search function (63.8%), and the member resource library (50.2%). The survey sample is mostly female (69.6%), non-Hispanic white (84.1%), and self-identified as a cancer survivor (49.8%), or both cancer survivor and cancer caregiver (31.9%). A larger number of survey respondents reported head and neck cancer (12.5%), relative to cancer incidence/prevalence data.

Conclusions

The volume of CSN traffic suggests high demand among cancer survivors and caregivers for informational and/or emotional support from other cancer survivors and caregivers. CSN may be particularly beneficial for individuals with rare cancers. Furthermore, this study documents a group of individuals whose cancer experience is multifaceted (e.g., survivors became caregivers or vice versa), and for whom CSN has the capacity to provide support at multiple points during their cancer experiences.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

CSN is a free, internet-based social networking site available to all cancer survivors and caregivers, worldwide. Evaluation of the site is ongoing and will be used to inform improvements to usability, reach, recruitment, retention, and potential health impact(s) of this valuable resource.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hewitt M, Herdman R, Holland J. Meeting psychosocial needs of women with breast cancer. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004.

Puts MT, Papoutsis A, Springall E, Tourangeau AE. A systematic review of unmet needs of newly diagnosed older cancer patients undergoing active cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(7):1377–94.

From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. 2006, Washington, DC: National Academies Press. 534 pages.

Hanly P, Céilleachair AÓ, Skally M, O’Leary E, Kapur K, Fitzpatrick P, et al. How much does it cost to care for survivors of colorectal cancer? Caregiver’s time, travel and out-of-pocket costs. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(9):2583–92.

Weaver KE, Forsythe LP, Reeve BB, Alfano CM, Rodriguez JL, Sabatino SA, et al. Mental and physical health-related quality of life among U.S. cancer survivors: population estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2012. 21(11):2108–17.

Mayer DK, Nasso SF, Earp JA. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):e11–8.

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):271–89.

Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1227–34.

Lambert SD, Harrison JD, Smith E, Bonevski B, Carey M, Lawsin C, et al. The unmet needs of partners and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2012;2(3):224–30.

Porter LS, Dionne-Odom JN. Supporting cancer family caregivers: how can frontline oncology clinicians help? Cancer. 2017;123(17):3212–5.

Luszczynska A, Pawlowska I, Cieslak R, Knoll N, Scholz U. Social support and quality of life among lung cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2013;22(10):2160–8.

Nausheen B, Gidron Y, Peveler R, Moss-Morris R. Social support and cancer progression: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(5):403–15.

Usta YY. Importance of social support in cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(8):3569–72.

Gonzalez-Saenz de Tejada M, et al. Association between social support, functional status, and change in health-related quality of life and changes in anxiety and depression in colorectal cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2017;26(9):1263–9.

Hoey LM, Ieropoli SC, White VM, Jefford M. Systematic review of peer-support programs for people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(3):315–37.

Gottlieb BH, Wachala ED. Cancer support groups: a critical review of empirical studies. Psychooncology. 2007;16(5):379–400.

Mead S, MacNeil C. Peer support: what makes it unique? Int J Psychosoc Rehabil. 2006;10(2):29–37.

Hartzler A, Pratt W. Managing the personal side of health: how patient expertise differs from the expertise of clinicians. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e62.

Bouma G, Admiraal JM, de Vries EGE, Schröder CP, Walenkamp AME, Reyners AKL. Internet-based support programs to alleviate psychosocial and physical symptoms in cancer patients: a literature analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;95(1):26–37.

Capurro D, Cole K, Echavarría MI, Joe J, Neogi T, Turner AM. The use of social networking sites for public health practice and research: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e79.

Eysenbach G, Powell J, Englesakis M, Rizo C, Stern A. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. Bmj. 2004;328(7449):1166.

Griffiths KM, Calear AL, Banfield M. Systematic review on Internet Support Groups (ISGs) and depression (1): do ISGs reduce depressive symptoms? J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(3):e40.

Hong Y, Pena-Purcell NC, Ory MG. Outcomes of online support and resources for cancer survivors: a systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(3):288–96.

McCaughan E, et al. Online support groups for women with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:Cd011652.

Zhang S, O’Carroll Bantum E, Owen J, Bakken S, Elhadad N. Online cancer communities as informatics intervention for social support: conceptualization, characterization, and impact. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(2):451–59.

Graham AL, Papandonatos GD, Zhao K. The failure to increase social support: it just might be time to stop intervening (and start rigorously observing). Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(4):816–20.

Owen JE, O’Carroll Bantum E, Pagano IS, Stanton A. Randomized trial of a social networking intervention for cancer-related distress. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51:661–72.

Framework for program evaluation in public health. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1999;48(Rr-11):1–40.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7.

Yalom I, Molyn L. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. 5th edition ed. New York: Basic Books; 2005.

Portier K, Greer GE, Rokach L, Ofek N, Wang Y, Biyani P, et al. Understanding topics and sentiment in an online cancer survivor community. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2013;2013(47):195–8.

Westmaas JL, McDonald B, Portier K. Topic modeling of smoking- and cessation-related posts to the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Survivor Network (CSN): implications for cessation treatment for cancer survivors who smoke. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19:952–9.

Zhao K, Yen J, Greer G, Qiu B, Mitra P, Portier K. Finding influential users of online health communities: a new metric based on sentiment influence. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e2):e212–8.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire, United States Department of health and Human Services, Editor. 2007: Atlanta: United States.

Carron-Arthur B, Ali K, Cunningham JA, Griffiths KM. From help-seekers to influential users: a systematic review of participation styles in online health communities. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(12):e271.

Wang YC, Kraut RE, Levine JM. Eliciting and receiving online support: using computer-aided content analysis to examine the dynamics of online social support. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(4):e99.

Petric G, Atanasova S, Kamin T. Ill literates or illiterates? Investigating the eHealth literacy of users of online health communities. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e331.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30.

Thome N, Garcia N, Clark K. Psychosocial needs of head and neck cancer patients and the role of the clinical social worker. Cancer Treat Res. 2018;174:237–48.

Buga S, Banerjee C, Salman J, Cangin M, Zachariah F, Freeman B. Supportive care for the head and neck cancer patient. Cancer Treat Res. 2018;174:249–70.

Cohen EE, LaMonte S, Erb NL, Beckman KL, Sadeghi N, Hutcheson KA, et al. American cancer society head and neck cancer survivorship care guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(3):203–39.

Smith JD, Shuman AG, Riba MB. Psychosocial issues in patients with head and neck cancer: an updated review with a focus on clinical interventions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(9):56.

Rhoten BA, Murphy B, Ridner SH. Body image in patients with head and neck cancer: a review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(8):753–60.

Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Wells KB, Jones L, et al. An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:1–22.

Collins LM, Murphy SA, Bierman KL. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prev Sci. 2004;5(3):185–96.

Hekler EB, Michie S, Pavel M, Rivera DE, Collins LM, Jimison HB, et al. Advancing models and theories for digital behavior change interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(5):825–32.

Mohr DC, Schueller SM, Montague E, Burns MN, Rashidi P. The behavioral intervention technology model: an integrated conceptual and technological framework for eHealth and mHealth interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(6):e146.

Wilbur J, Kolanowski AM, Collins LM. Utilizing MOST frameworks and SMART designs for intervention research. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64(4):287–9.

Hekler EB, Klasnja P, Riley WT, Buman MP, Huberty J, Rivera DE, et al. Agile science: creating useful products for behavior change in the real world. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6(2):317–28.

Patrick K, Hekler EB, Estrin D, Mohr DC, Riper H, Crane D, et al. The pace of technologic change: implications for digital health behavior intervention research. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(5):816–24.

Acknowledgements

We thank The American Cancer Society Survivors Network® members for their time in planning the evaluation and completing the evaluation surveys. Several researchers provided input and expertise to the creation of the instrument used in the longitudinal survey including J. Lee Westmaas (American Cancer Society Behavioral Research Center) and Robert Kraut and colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University. CSN research also benefited from John Yen and colleagues at The Pennsylvania State University who provided invaluable insights into the assessment of online communities. Finally, we acknowledge Greta Greer (Retired, American Cancer Society), as the original creator of the Cancer Survivors Network.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Prior to data collection, IRB approval (Morehouse School of Medicine IRB # 516176) was obtained. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Furthermore, all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any animal research.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fallon, E.A., Driscoll, D., Smith, T. et al. Description, characterization, and evaluation of an online social networking community: the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Survivors Network®. J Cancer Surviv 12, 691–701 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0706-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0706-8