Abstract

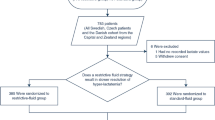

Prognostication in sepsis is limited by disease heterogeneity, and measures to risk-stratify patients in the proximal phases of care lack simplicity and accuracy. Hyperlactatemia and vasopressor dependence are easily identifiable risk factors for poor outcomes. This study compares incidence and hospital outcomes in sepsis based on initial serum lactate level and vasopressor use in the emergency department (ED). In a retrospective analysis of a prospectively identified dual-center ED registry, patients with sepsis were categorized by ED vasopressor use and initial serum lactate level. Vasopressor-dependent patients were categorized as dysoxic shock (lactate >4.0 mmol/L) and vasoplegic shock (≤4.0 mmol/L). Patients not requiring vasopressors were categorized as cryptic shock major (lactate >4.0 mmol/L), cryptic shock minor (>2.0 and ≤4.0 mmol/L), and sepsis without lactate elevation (≤2.0 mmol/L). Of 446 patients included, 4.9% (n = 22) presented in dysoxic shock, 11.7% (n = 52) in vasoplegic shock, 12.1% (n = 54) in cryptic shock major, 30.9% (n = 138) in cryptic shock minor, and 40.4% (n = 180) in sepsis without lactate elevation. Group mortality rates at 28 days were 50.0, 21.1, 18.5, 12.3, and 7.2%, respectively. After adjusting for potential confounders, odds ratios for mortality at 28 days were 15.1 for dysoxic shock, 3.6 for vasoplegic shock, 3.8 for cryptic shock major, and 1.9 for cryptic shock minor, when compared to sepsis without lactate elevation. Lactate elevation is associated with increased mortality in both vasopressor dependent and normotensive infected patients presenting to the emergency department (ED). Cryptic shock mortality (normotension + lactate >4 mmol/L) is equivalent to vasoplegic shock mortality (vasopressor requirement + lactate <4 mmol/L) in our population. The odds of normotensive, infected patients decompensating is three to fourfold higher with hyperlactemia. The proposed Sepsis-3 definitions exclude an entire group of high-risk ED patients. A simple classification in the ED by vasopressor requirement and initial lactate level may identify high-risk subgroups of sepsis. This study may inform prognostication and triage decisions in the proximal phases of care.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Elixhauser A, Friedman B, Stranges E (2006) Septicemia in U.S. hospitals (2009) statistical brief #122, in healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP) statistical briefs. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (US), Rockville

Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S et al (2014) Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000–2012. JAMA 311(13):1308–1316. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.2637

Yealy DM, Kellum JA, Huang DT et al (2014) A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med 370(18):1683–1693. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401602

Arise Investigators and ANZICS Clinical Trials Group (2014) Goal-directed resuscitation for patients with early septic shock. N Engl J Med 371(16):1496–1506. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1404380

Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS et al (2015) Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med 372(14):1301–1311. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500896

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC et al (2003) 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Intensive Care Med 29:530–538. doi:10.1007/s00134-003-1662-x

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW et al (2016) The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 315(8):801–810. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.0287

Nguyen HB, Rivers EP, Havstad S et al (2000) Critical care in the emergency department a physiologic assessment and outcome evaluation. Acad Emerg Med 7(12):1354–1361. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00492.x

Jones AE, Trzeciak S, Kline JA (2009) The sequential organ failure assessment score for predicting outcome in patients with severe sepsis and evidence of hypoperfusion at the time of emergency department presentation. Crit Care Med 37(5):1649. doi:10.1097/ccm.0b013e31819def97

Marshall JC, Cook DJ, Christou NV, Bernard GR, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ (1995) Multiple organ dysfunction score: a reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit Care Med 23(10):1638–1652. doi:10.1097/00003246-199510000-00007

Howell MD, Talmor D, Schuetz P, Hunziker S, Jones AE, Shapiro NI (2011) Proof of principle: the predisposition, infection, response, organ failure sepsis staging system. Crit Care Med 39(2):322–327. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182037a8e

Shapiro NI, Wolfe RE, Moore RB, Smith E, Burdick E, Bates DW (2003) Mortality in emergency department sepsis (MEDS) score: a prospectively derived and validated clinical prediction rule. Crit Care Med 31(3):670–675. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000054867.01688.D1

Jones AE, Saak K, Kline JA (2008) Performance of the mortality in emergency department sepsis score for predicting hospital mortality among patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Am J Emerg Med 26(6):689–692. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2008.01.009

Shapiro NI, Howell MD, Talmor D et al (2005) Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection. Ann Emerg Med 45(5):524–528. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.006

Wacharasint P, Nakada TA, Boyd JH, Russell JA, Walley KR (2012) Normal-range blood lactate concentration in septic shock is prognostic and predictive. Shock 38(1):4–10. doi:10.1097/SHK.0b013e318254d41a

Mikkelsen ME, Miltiades AN, Gaieski DF et al (2009) Serum lactate is associated with mortality in severe sepsis independent of organ failure and shock. Crit Care Med 37(5):1670–1677. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fcf68

Howell MD, Donnino M, Clardy P, Talmor D, Shapiro NI (2007) Occult hypoperfusion and mortality in patients with suspected infection. Intensive Care Med 33(11):1892–1899. doi:10.1007/s00134-007-0680-5

Sterling SA, Puskarich MA, Shapiro NI et al (2013) Characteristics and outcomes of patients with vasoplegic versus tissue dysoxic septic shock. Shock 40(1):11. doi:10.1097/shk.0b013e318298836d

Ranzani OT, Monteiro MB, Ferreira EM, Santos SR, Machado FR, Noritomi DT (2013) Reclassifying the spectrum of septic patients using lactate: severe sepsis, cryptic shock, vasoplegic shock and dysoxic shock. Rev Bras Terapia Intensiv 25(4):270–278. doi:10.5935/0103-507x.20130047

Thomas-Rueddel DO, Poidinger B, Weiss M et al (2015) Hyperlactatemia is an independent predictor of mortality and denotes distinct subtypes of severe sepsis and septic shock. J Crit Care 30(2):439e1–e6. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.10.027

Tang Y, Choi J, Kim D et al (2014) Clinical predictors of adverse outcome in severe sepsis patients with lactate 2 to 4 mM admitted to the hospital. QJM 108(4):279–287. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcu186

Arnold RC, Sherwin R, Shapiro NI et al (2013) Multicenter observational study of the development of progressive organ dysfunction and therapeutic interventions in normotensive sepsis patients in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 20(5):433–440. doi:10.1111/acem.12137

Song YH, Shin TG, Kang MJ et al (2012) Predicting factors associated with clinical deterioration of sepsis patients with intermediate levels of serum lactate. Shock 38(3):249–254. doi:10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182613e33

Hernandez G, Castro R, Romero C et al (2011) Persistent sepsis-induced hypotension without hyperlactatemia: is it really septic shock? J Crit Care 26(4):435–439. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.09.007

Hernandez G, Bruhn A, Castro R et al (2012) Persistent sepsis-induced hypotension without hyperlactatemia: a distinct clinical and physiological profile within the spectrum of septic shock. Crit Care Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2012/536852

Puskarich MA, Trzeciak S, Shapiro NI, Heffner AC, Kline JA, Jones AE (2011) Outcomes of patients undergoing early sepsis resuscitation for cryptic shock compared with overt shock. Resuscitation 82(10):1289–1293. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.06.015

Hwang SY, Shin TG, Jo IJ et al (2014) Association between hemodynamic presentation and outcome in sepsis patients. Shock 42(3):205–210. doi:10.1097/SHK.0000000000000205

Dugas AF, Mackenhauer J, Salciccioli JD, Cocchi MN, Gautam S, Donnino MW (2012) Prevalence and characteristics of nonlactate and lactate expressors in septic shock. J Crit Care 27(4):344–350. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.01.005

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S et al (2001) Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 345(19):1368–1377. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010307

Donnino MW, Nguyen B, Jacobsen G, Tomlanovich M, Rivers EP (2003). Cryptic septic shock: a sub-analysis of early, goal-directed therapy. Chest 124(4 meeting abstracts):90S-b

Wira CR, Francis MW, Bhat S, Ehrman R, Conner D, Siegel M (2014) The shock index as a predictor of vasopressor use in emergency department patients with severe sepsis. Western J Emerg Med 15(1):60

Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR (2001) Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 29(7):1303–1310. doi:10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002

Poutsiaka DD, Davidson LE, Kahn KL, Bates DW, Snydman DR, Hibberd PL (2009) Risk factors for death after sepsis in patients immunosuppressed before the onset of sepsis. Scand J Infect Dis 41(6–7):469–479. doi:10.1080/00365540902962756

Tolsma V, Schwebel C, Azoulay E et al (2014) Sepsis severe or septic shock: outcome according to immune status and immunodeficiency profile. Chest 146(5):1205–1213. doi:10.1378/chest.13-2618

O’Brien JM, Lu B, Ali NA et al (2007) Alcohol dependence is independently associated with sepsis, septic shock, and hospital mortality among adult intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med 35(2):345–350. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000254340.91644.B2

Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Pilcher D, Cooper DJ, Bellomo R (2015) Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 372(17):1629–1638. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1415236

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Drs. Sundeep R. Bhat, Mellisa Wollan, and Martina T. Sanders-Spight for their assistance in the formulation and maintenance of the sepsis registry utilized in this study. We also acknowledge the generous funding support from the G.D. Hsiung Research Fellowship through the Yale School of Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

Study approved by the Yale Investigational Review Committee.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required for the study.

Funding

This study was funded by the G.D. Hsiung Research Fellowship, Yale School of Medicine, 2014.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Swenson, K.E., Dziura, J.D., Aydin, A. et al. Evaluation of a novel 5-group classification system of sepsis by vasopressor use and initial serum lactate in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med 13, 257–268 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-017-1607-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-017-1607-y