Abstract

This study focuses on the dwell-fatigue crack propagation behavior of IN718 manufactured via selective laser melting (SLM). The dwell-fatigue test condition is 823 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C) with a long 2160-s dwell-holding period. Effects of heat treatment and loading direction on dwell-fatigue crack propagation rates are studied. A grain boundary \(\delta \) precipitate seems to be slightly beneficial to the dwell-fatigue cracking resistance of SLM IN718. A comparison has been made between SLM IN718 and forged counterparts at different temperatures, indicating that a creep damage mechanism is likely dominant for SLM IN718 under the present test condition. A general discussion of the inferior creep resistance of SLM IN718 is also included. The anisotropic dwell-fatigue cracking resistance has also been studied and rationalized with the effective stress intensity factor calculated from finite element modeling.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Selective laser melting (SLM) is one of the most widely used additive manufacturing (AM) techniques for metallic materials. The extremely rapid and localized solidification during the SLM process results in quite different as-built microstructures compared with conventional cast or hot-worked ones. For critical Ni-base superalloy engine components, SLM shows overwhelming advantages over other non-AM processes for geometric complexities.[1] The attempts to manufacture Ni-base superalloy (IN718,[2–4] IN738LC,[5,6] Hastelloy X,[7,8,9] CM247LC[10,11,12] and IN625[13,14,15] components) via SLM have attracted much attention in the AM field in the past years. Most of these studies focused on microstructural studies, process parameter optimizations and monotonic mechanical properties (tensile test and hardness). Though promising, the reliability of these SLM Ni-base superalloys under dynamic and complicated service conditions still needs to be demonstrated.

IN718 is a \(\gamma ''\) strengthened Ni-base superalloy, and it is widely used for turbine disk materials. Turbine disk materials are usually subjected to dwell-fatigue loading during real engine operation, i.e., there is a dwell period at peak loading, in addition to the cyclic ramping up and down. By prolonging the dwell period and/or increasing the test temperature, the fatigue crack propagation in conventional IN718 has been largely accelerated and becomes time-dependently intergranular[16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] compared with the pure-cyclic fatigue condition. Two possible theories regarding environmentally assisted grain boundary attack, namely dynamic embrittlement (DE)[26] and stress-assisted grain boundary oxidation (SAGBO),[27] are suggested to explain this dwell effect, but there is still debate about which of these two theories is the actual one. On the other hand, it is also possible that creep happens during the dwell-fatigue test, depending on the relative resistance of creep and environmentally assisted grain boundary degradation for the specific microstructure under the test condition.

IN718 has been intensively studied in the AM field because of its excellent weldability. The typical SLM microstructure is very different from that of the hot-worked counterpart; please see the detailed microstructural study of SLM IN718 reported in our previous work.[3] This motivated the authors to study the dwell-fatigue cracking behaviors in the present study and demonstrate the reliability of SLM components in service conditions, which is important but has rarely been reported so far. Specific focuses will be on (1) the damage mechanism, (2) effects of heat treatments and (3) effect of anisotropy (loading parallel and perpendicular to the building direction). Comparison will also be made with the conventional counterparts reported in References 19, 24 and 28. The present study will contribute to the understanding of the dwell damage mechanism and the general inferior creep resistance of the typical SLM microstructure.

2 Experimental

2.1 Material and Heat Treatments

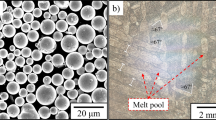

Gas atomized IN718 powder with a nominal size < 65 \(\mu \)m was used as the raw material for the SLM process. The nominal chemical composition of the gas atomized IN718 powder is given in Table I. The as-built blocks of \(35\,{\text {mm}} \times 39\,{\text {mm}} \times 10\,{\text {mm}}\) (see Figure 1(a)) were manufactured with an EOS M290 machine with standard process parameters.

In the present study, three different heat treatments were applied to achieve strength comparable to the forged counterpart. The heat treatment details are listed in Table II. The microstructures after heat treatments are compared in Figure 2. The applied three heat treatments do not remove the sub-grain/cell structures or significantly change the grain sizes. The most noticeable difference is the presence of \(\delta \) phase (see Figure 2). The SA condition has rod-like \(\delta \) at the grain boundaries and needle-like \(\delta \) in the grain interiors; the \(\delta \) volume fraction is about 0.63 pct. The HSA condition only has slightly bigger rod-like \(\delta \) (0.19 pct of volume fraction) at the grain boundaries, while \(\delta \) is absent in the HA condition. Tensile strength and ductility at room temperature are also comparable among these three conditions; please see Reference 3.

2.2 Dwell Fatigue Crack Propagation Tests

Compact tension (CT) geometry was adopted in the present study to investigate the crack propagation behaviors. Two sample orientations were tested to investigate the anisotropic cracking resistance: the N-type has the machined notch normal to the building direction, while the P-type has the machined notch parallel to the building direction, as shown in Figures 1(b) and (c). These CT specimens were first pre-cracked at room temperature under the pure-fatigue condition to generate a pre-crack of about 1.5 mm in length from the electrical discharge machined (EDM) notch tip. The pure-fatigue loading was under the load ratio of \(R = P_{\min }/P_{\max } = 0.05,\) load range of \(\Updelta P = P_{\max } - P_{\min } = 2500\) N and cyclic frequency of 10 Hz.

Dwell fatigue crack propagation tests were conducted in a 100-kN Zwick KAPPA 50 DS system at 823 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C) in laboratory air. Each cycle includes 10 seconds ramping up to the maximum load, 2160 seconds dwell period at the maximum and 10 seconds ramping down to the minimum load. The load ratio was \(R = P_{\min }/P_{\max } = 0.05.\) As shown in Table III, the \(\Updelta P\) applied for P-type specimens is 3000 N, while it is 4500 N for N-type specimens. Note that \(\Updelta P\) for N-type specimens was first set to 3000 N but did not give noticeable crack growth, until it was increased to 4500 N. During testing, the crack length was measured using a direct current potential drop (DCPD) system with a pulsed 10 A current per ASTM E647. The crack length was first derived from the potential drop measurements using the Johnson analytical formula[29] for the CT specimen, assuming that a straight through-thickness crack front was maintained during the test. Later, the crack length was corrected by fracture surface inspection: the pre-crack front and dwell-fatigue crack front were identified, and then the dwell-fatigue crack growth was averaged over about 20 measurements at different locations on the fracture surface. The stress intensity factor range \(\Updelta K\) was also calculated according to ASTM E647.

2.3 Microscopy Analysis

The tested specimens were first cut into two halves along the planes perpendicular to the crack surface: one half was then forced open by a tensile load to reveal the dwell-fatigue crack surface, and the other half was polished to reveal the crack cross section. The crack cross sections were mechanically ground successively from 500 to 4000 grit and polished with a diamond suspension from 3 to 1/4 \(\mu \)m and finally with Struers OP-U colloidal silica suspension. A Hitachi SU70 FEG scanning electron microscope, equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and an electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) system from Oxford Instruments, was employed to detail the microstructural features. Texture and grain misorientation measurements were performed with a scanning step size of 1 \(\mu \)m and analyzed with HKL Channel 5 software.

2.4 Finite Element Modeling

For crack configurations for which no simple handbook solution exists (i.e., for cracks deviating from the pre-cracking plane), the stress intensity factor was calculated using the Abaqus 6.12 commercial finite element code. The CT specimen was modeled in 2D plane strain using six-node quadratic elements. Around the crack tip, several measures were taken to more accurately capture the stress singularity: (1) the mesh was refined, (2) collapsed node elements were used, and (3) the location of the midside nodes was shifted toward the crack tip. Loads were applied as pressure on the half of the pin hole in contact with the pin during loading. The specimen was constrained vertically at the symmetry line and horizontally at the pin holes. Figure 3 shows the mesh and illustrates the applied boundary condition. The stress intensity factors in modes I and II, \(K_{\text {I}}\) and \(K_{\text {II}},\) were calculated using elastic constants of \(E = 210\) GPa and \(\nu = 0.3\) and by using Abaqus’ built-in interaction integral method. The stress intensity factors were calculated along a pre-defined crack path chosen to correspond to experimental observations.

3 Results

3.1 Crack Path and Fracture Morphology

Comparisons of the crack paths and fracture surface morphologies have been made on different heat-treated conditions of both P- and N-type specimens. However, the general dwell crack propagation direction and fracture surface feature depend more on specimen orientation than heat treatment condition. For brevity, crack paths and fracture surfaces are only compared between the P- and N-type orientations, but not between different heat treatment conditions.

The crack path of a P-type specimen is shown in Figure 4(a). The dwell crack generally propagates on the same plane as the pre-crack (in-plane cracking), and the propagation direction is perpendicular to the loading direction and parallel to the building direction. The P-type fracture surface (see Figure 4(b)) shows that, as the dwell crack propagates, the fracture mode changes gradually from intergranular to transgranular, accompanied by the fracture surface color changing from green-blue to dark blue and finally to dark brown.

Such a coloring and intergranular/transgranular fracture correlation also holds true for the N-type fracture surface, as shown in Figure 5(b). Differently, during dwell tests the pre-crack branches into two dwell cracks, one propagating upward and the other downward. These two dwell cracks largely deviate from the pre-crack plane (out-of-plane cracking), and they seem to be curved instead of being straight to the end. Also note that these two dwell cracks are not symmetric and not equally long. Examining the other fractured specimen of the same orientation (not shown here) reveals a different deviation angle and almost the absence of the downward propagating dwell cracks. Therefore, for the N-type orientation, there seems to be no certain pattern to describe the dwell cracking behavior after pre-cracking, which possibly depends on the local grain boundary alignment and the stress state ahead of the pre-cracking.

(a) Crack path shown from a side surface of a P-type CT specimen after the test, indicating that the dwell crack continues propagating on the notch/pre-crack plane. The crack path is parallel to the BD but perpendicular to the loading direction. (b) The fracture surface of a P-type CT specimen after the test, showing the change in fracture mode as the dwell crack propagates (Color figure online)

(a) Crack path shown from a side surface of a N-type CT specimen after the test, indicating that the crack path largely deviates from the notch/pre-crack plane. (b) Fracture surface of an N-type CT specimen after the test, showing the change in fracture mode as the dwell crack propagates (Color figure online)

3.2 Validity of Crack Length Measurement and Correlation with \(\Updelta K\)

It is worth briefly discussing the validity of crack length measurement/correction and \(\Updelta K\) in both the P- and N-type cases before the crack growth rate data are presented.

For P-type specimens, the fracture is under the typical mode I as the dwell crack plane is perpendicular to the loading direction, and the crack length monitored by DCPD during testing can be simply corrected with fracture surface measurements after the test. However, for N-type specimens, such a large deviation angle from the pre-crack plane invalidates the pure mode I fracture per ASTM E647. In addition, DCPD might not even be able to roughly monitor the out-of-plane crack growth during testing per ASTM E647, especially when two dwell cracks propagate simultaneously. Therefore, for these N-type cases, calculation of the stress intensity factor range \(\Updelta K\) with the DCPD data is less reliable.

Instead of accurately quantifying the crack growth rate \({\text {d}}a/{\text {d}}N\) as a function of the stress intensity factor range \(\Updelta K\) for the N-type specimens, it would be more interesting to show the anisotropic dwell cracking resistance, if any, between N- and P-type orientations.

The dwell fatigue test on the SA N-type specimen was started with a \(\Updelta P\) of 3000 N, exactly as for P-type specimens. However, it did not result in noticeable crack growth even after about a week of test time. Increasing the load range to \(\Updelta P\) to 3500 N and further to 4000 N still did not really propagate the crack. Crack growth was not noticeable until the \(\Updelta P\) was increased to 4500 N. Although these 0 mm/cycle data were not shown here for brevity, they do suggest that the N-type orientation has better dwell cracking resistance than the P-type orientation at a similar \(\Updelta K.\)

3.3 Crack Growth Rate

The crack growth rate \({\text {d}}a/{\text {d}}N\) is plotted vs the stress intensity factor range \(\Updelta K\) in Figure 6 for both N- and P-type specimens of different heat-treated conditions. The P-type crack growth rate is calculated per ASTM E647 and is reliable. For the N-type specimens, due to the aforementioned invalidities per ASTM E647, no quantitative crack growth rate data are achieved in the present study; instead, the present authors would simply adapt the crack length measured from DCPD and apply the Mode I configuration to calculate the crack growth rate. Such a simplification is, at least, able to indicate the reliable anisotropic dwell cracking resistance between N- and P-type specimens.

As shown in Figure 6, the N-type orientation has noticeably better cracking resistance than the P-type orientation. Among the heat treatments of P-type specimens, it shows that the HA treatment (without grain boundary \(\delta \)) gives a faster crack propagation rate than the SA and HSA treatments (with grain boundary \(\delta \)). The SA and HSA conditions show very similar cracking resistance.

4 Discussion

4.1 Damage Mechanism: Creep or Environmentally Assisted Grain Boundary Attack?

The representative fractured cross sections are shown in Figure 7 to reveal the damage mechanism, with specific focus on the secondary cracks. The beginning, middle and end parts of the HA P-type dwell crack path are shown in Figures 7(a), (b) and (c) respectively. As the dwell crack propagates, the main crack seems to be progressively discontinuous, and the secondary cracks gradually become more frequent and wide open. Secondary cracks marked in Figures 7(a), (b) and (c) are magnified in Figures 7(d), (e) and (f), respectively. Important features of these secondary cracks can be summarized as follows:

-

(1)

Discontinuous and almost perpendicular to the loading direction.

-

(2)

Not branched or originating from the main crack.

-

(3)

Associated with high-angle (\(>15\) degrees, confirmed with EBSD) grain boundaries.

-

(4)

Associated with plastic deformation as evident from the backscatter contrast.

These features probably indicate that the cracking mechanism is at least predominantly creep damage rather than environmentally assisted grain boundary attack. The essential idea of environmentally assisted grain boundary attack (including both DE and SAGBO) involves the diffusion of oxygen along the grain boundary ahead of the crack tip under mechanical stress. As mentioned, the secondary cracks are not branched or originating from the main crack, indicating that they are not directly exposed to the oxygen atmosphere. If either DE or SAGBO is tenable, the transportation of oxygen across a few grains will be required. Such a long-range transportation via lattice diffusion seems less likely considering the relatively low test temperature of 823 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C). Furthermore, some random grain boundaries are crossed during this long-range transportation but are not cracked, which might also violate the DE or SAGBO mechanism. With this in mind, environmentally assisted grain boundary attack is not believed to be the principle damage mechanism.

On the other hand, if a creep mechanism is assumed, it would be interesting to compare the \({\text {d}}a/{\text {d}}t\)vsK (or \(K_{\max }\)) behaviors with the conventionally manufactured counterparts that are tested under the creep (sustained loading) crack growth condition at different temperatures. The comparison shown in Figure 8 is made on a forged IN718 (from Reference 19), an alloy 718 (from Reference 28) and HA P-type specimen in the present study. The \({\text {d}}a/{\text {d}}t\)vsK (or \(K_{\max }\)) relationships can be established by a Paris’ law type equation for all cases shown:

where the proportional constant A is a temperature- and microstructure-dependent term, and the stress intensity exponent m is similar but not identical to the power-law creep stress exponent.[30] Interestingly, for the forged IN718 counterpart, the exponent m is almost identical at temperatures of 823 K, 873 K and 923 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C, 600 \(^{\circ }\)C and 650 \(^{\circ }\)C, respectively), which might indicate that the time-dependent crack propagation mechanism is identical in these three cases. Metallographic cross sections of the aforementioned forged IN718 specimens are not available for detailed damage examination in the present study. However, a rough speculation can be made by comparing the crack paths from long dwell-time tests reported in [24,31] for the same batch of forged IN718 as in Figure 8: environmentally assisted grain boundary attack, instead of creep damage, is the dominant damage mechanism under 2160 seconds dwell condition at both 823 K and 923 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C and 650 \(^{\circ }\)C) for the forged counterpart.

Comparison of \({\text {d}}a/{\text {d}}t\)vs\(K_{\max }\) or K between a forged 718 (creep loading at 823 K, 873 K and 923 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C, 600 \(^{\circ }\)C and 650 \(^{\circ }\)C[19]), a C&W IN718 (creep loading at 1033 K (760 \(^{\circ }\)C)[28]) and SLM HA P-type specimen of the present study at 823 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C)

Actually, this indicates that mechanically sustained load alone does not necessarily result in creep damage, since temperature and microstructure (intrinsic creep/deformation and oxidation resistances) are also important factors affecting whether creep damage occurs. Generally, for IN718, at the temperature of 1033 K (760 \(^{\circ }\)C) creep surely happens. Reference 32 suggests that for standard aged IN718 with an average grain size of 150 \(\mu \)m, the onset of tertiary creep occurs rather early at 1033 K (760 \(^{\circ }\)C), during which regime creep strain/damage dramatically accumulates with time. The creep crack growth at 1033 K (760 \(^{\circ }\)C) reported by Sadananda and Shahinian[28] shows that the time-dependent crack growth rate significantly increases with K, as shown in Figure 8 with a stress intensity exponent m of 8.45. Therefore, such a high value of the stress intensity exponent m possibly indicates that creep, specifically tertiary creep, is responsible for the time-dependent cracking behavior in Sadananda’s case. Similarly, it is quite convincing that creep (specifically in the tertiary creep regime) is the dominant cracking mechanism for the SLM HA P-type case in the present study, which has an even larger m of 12.18. To the best of our knowledge, creep tests on SLM IN718 reported in the literature have been conducted at 903 K (630 \(^{\circ }\)C)[33] and 923 K (650 \(^{\circ }\)C).[34,35] Specifically, in Reference 35, under 923 K (650 \(^{\circ }\)C)/550 MPa, the creep properties of SLM IN718 are noticeably inferior to the cast&wrought (C&W) counterpart: the steady creep regime is almost absent, and the onset of tertiary creep occurs quite early for both the as-built and heat-treated conditions. The early onset of tertiary creep[35] is believed to be consistent with the relatively fast crack growth rate in the present SLM cases, which is associated with the high-stress intensity exponent m in Figure 8.

4.2 Effects of Grain Boundary \(\delta \) and Grain Boundary Sliding

Another proof of creep damage, instead of environmentally assisted grain boundary attack, can be presented by the effects of grain boundary \(\delta \) on the crack propagation rate. If environmentally assisted grain boundary attack was the case, the crack propagation rate of the HA condition without grain boundary \(\delta \) would be the lowest among these three conditions, since the grain boundary \(\delta \) has been reported as susceptible to forming brittle \({\hbox {Nb}}_{2} {\hbox {O}}_{5}\)[36,37] and accelerates oxygen-related crack propagation. However, as shown in Figure 6, grain boundary \(\delta \) slightly reduces the crack propagation rate, and the HA P-type condition without grain boundary \(\delta \) has the highest crack propagation rate.

The intergranular secondary crack tips of SLM P-type specimens are shown in Figure 9 to compare the effects of grain boundary \(\delta \) precipitates on the dwell cracking behaviors. As shown in Figures 9(a) and (b), grain boundary \(\delta \) precipitates always associate with isolated micro-voids, and the intergranular cracking seems to develop by growth and linkage of the micro-voids. Differently, in the clean grain boundary case (Figure 9(c)), creep damage forms isolated wedge cracks, and the crack propagates by extension and linkage of the wedge cracks. This is a faster process than that of micro-voids, as shown by the fastest crack propagation rate of the HA specimen in Figure 6. Such an observation is generally in agreement with the fact that the presence of the grain boundary precipitate inhibits grain boundary sliding and therefore reduces the creep rate. GBS might play an important role in the cracking behavior in this case; it is also possible that other creep mechanisms, other than GBS, are operative simultaneously and contribute to the total cracking rate. Further study is needed to better understand the creep mechanism for such an SLM microstructure.

4.3 Creep at 823 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C)? A General Discussion on Inferior Creep Resistance of SLM IN718

Creep was discussed in the previous subsections as the dwell-fatigue cracking mechanism for the SLM specimens in the present study. However, one question might arise: is the test temperature of 823 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C) too low for creep to happen?

The creep mechanisms of C&W IN718 have been systematically studied, with emphasis on the steady-state creep at over 873 K (600 \(^{\circ }\)C), in References 38, 39, 40 and 41. However, limited creep data are available for SLM materials, and their creep mechanisms are not well understood compared with the conventional counterparts. Kuo et al.[42] suggested that the high dislocation density and subgrain boundaries prohibit dislocation motions and cause stress concentrations in the SLM IN718 materials, which lead to inferior creep resistance. This sounds plausible in the first place, but becomes questionable if considering a ‘work-hardening’ effect of the aforementioned high dislocation density and subgrain boundaries on the primary creep rate. Reference 34 clearly shows that SLM IN718 has an at least four orders of magnitude higher primary creep rate than the C&W counterpart. This indicates that the high dislocation density and subgrain boundary do not actually ‘work-harden’ the SLM material or provide better creep resistance from the very beginning.

Furthermore, one might argue that the primary stage is just transient and secondary creep should be of interest. Here, we just adapt the steady-state/minimum creep rates and loading conditions of SLM IN718 and C&W IN718 in References 34 and 35 to determine the possible factors contributing to the inferior creep resistance of the SLM material, with the creep rate equation and some material constants from Reference 41:

where \(A^{*}\) is a material constant and is proportional to the lattice/grain boundary diffusion, G is the shear modulus, b is the Burgers vector, k is the Boltzmann constant, T is temperature in K, R is the gas constant, \(\sigma _{\text {a}}\) is the applied stress, \(\sigma _{0}\) is the back stress inhibiting dislocation movement, \(Q_{\text {e}}\) is the effective activation energy, and \(n_{\text {e}}\) is the effective stress exponent. The main creep parameters of SLM and C&W IN718 are listed in Table IV. As seen, the minimum creep rate of SLM is at least three orders of magnitude higher than that of the C&W counterpart. The back stress \(\sigma _{0},\) effective stress component \(n_{\text {e}}\) and effective activation energy \(Q_{\text {e}}\) for the C&W counterpart are adapted from Reference 41, while they remain unknown for the SLM material.

Assuming that the other parameters remain constant and that the same creep mechanism is active, to have a three orders of magnitude higher minimum creep rate than the C&W counterpart, each of the following parameters for SLM IN718 can be considered separately:

-

Effective activation energy \(Q_{\text {e}}\) should be about 197 kJ/mol, which is much less than the creep activation energy of 265 to 295 for pure Ni and Ni-Cr alloys quoted in Reference 43 and might be unreasonable.

-

The back stress \(\sigma _{0}\) and effective stress component \(n_{\text {e}}\): mathematically, for instance, with a slightly smaller back stress \(\sigma _{0}\) of 480 MPa and a slightly lower stress exponent \(n_{\text {e}}\) of 1.1, would give such a two to three orders of magnitude higher minimum creep rate.

-

The grain boundary diffusivity \(D_{\text {gb}}\) contribution in the material constant \(A^{*}\) should also be three orders of magnitude higher than that of the C&W counterpart, which might be less likely to have random high-angle grain boundaries at the same temperature.

With very limited data, it is impossible to identify the exact contribution of each possibility to the overall creep resistance; possibly all these parameters within reasonable ranges simultaneously lead to a much higher creep rate in the SLM materials as observed. Interestingly, the combination of lower back stress \(\sigma _{0}\) and the effective stress component \(n_{\text {e}}\) is very similar to the case of IN718 sheets exposed to cold rolling (CR) and low-temperature–short-term annealing as reported in Reference 38. This suggests one possible explanation: the SLM material is largely deformed and is not fully recovered after heat treatment. Such a possibility was not mentioned in Kuo et al.[34,35] Here, we construct recrystallization fraction maps on a forged IN718 and SLM HA specimen, of which the forged IN718 is the same batch as in Gustafsson and Lundström[19] and is in as-received heat-treated condition, and the SLM HA is the one studied in the present study and is in as-heat-treated condition. As shown in Figure 10, the forged counterpart has a 69.79 pct recrystallization fraction, which is much higher than the 3.02 pct of the SLM HA condition. Surprisingly, about 25.51 pct of the microstructure in the SLM HA condition is indexed as deformed. The 71.47 pct substructured fraction in Figure 10 is consistent with the very typical cell/subgrain microstructure in the as-built, short-time or low-temperature heat-treated SLM microstructure. Generally, the lower fraction of recrystallization indicates a less perfect or less well-annealed material and possibly a greater degradation or deformation of the microstructure. The comparison in Figure 10 clearly suggests that the SLM IN718 after the conventional heat treatment routine is in a degraded or deformed condition, even though it has not physically been through any mechanical deformation process.

Recrystallized, substructured and deformed fractions of (a) forged IN718 in as-received and (b) SLM HA specimens in as-heat-treated condition. The minimum misorientation angle to separate subgrains is set as 1° by default in the HKL Channel 5 program. With this angle, it means: if the average misorientation between subgrains within one grain is < 1°, then the grain is indexed as recrystallized; if the average misorientation between subgrains within one grain is < 1°, but the misorientation angle between any subgrains is > 1°, then the grain is indexed as substructured; if the average misorientation between subgrains within one grain is > 1º, then the grain is indexed as deformed

This degradation speculation is tenable, and it is consistent with the early onset of tertiary creep observed in Reference 34. The microstructural degradation possibly resulted from the rapid solidification during the SLM process. From the point of view of rapid solidification, welding is similar to the SLM process. The stress rupture properties of welded IN718 compared with the base/parent IN718 also show inferiority and early onset of tertiary creep.[44,45,46] If this is the case, creep damage at 823 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C) during the present dwell-fatigue tests might become possible, because creeping a largely pre-deformed specimen can be much easier. The detailed creep mechanism for the SLM material is still open to further investigation with more experimental data.

4.4 Effects of Notch Orientation

Although the quantitative comparison of notch orientation effects on the dwell-fatigue crack propagation rates is not available (Section III–B), it is still interesting to qualitatively discuss the anisotropic dwell-fatigue resistance. The crack paths of SA P- and N-type specimens are compared in Figure 11. As seen, the orientation of the crack path regarding the loading direction is very different between the P- and N-type specimens. However, the magnified secondary cracks in Figures 11(c) and (d) indicate that the dwell damage develops and propagates in the same manner: by nucleation and linkage of micro-voids at the grain boundary \(\delta .\) If looking carefully at Figure 10(b), one finds that the columnar grain boundaries mostly deviate by a small angle or even parallel to the building direction. Therefore, the anisotropy is possibly mainly due to the different angles between the columnar grain boundaries and loading direction of P- and N-type cases, and in the N-type cases the effective stress intensity factor is lower.

A simplified kinked crack adapted from the SA N-type specimen was analyzed in a finite element model to reveal the possible fracture behavior and the corresponding stress intensity factor. The geometry of the kinked crack is as illustrated in Figure 12(a), and the kinked crack length is the sum of the pre-crack (12.5 mm) and dwell-crack lengths. Load was set to both 3000 N and 4500 N, which correspond to the load for the P- and N-type specimens cases. Figure 12(a) shows that mode I fracture dominates, and mode II fracture fades with the kinked dwell crack propagation. The effective stress intensity factor of the kinked crack is calculated from the combination of \(K_{\text {I}}\) and \(K_{\text {II}},\) and is compared with the pure \(K_{\text {I}}\) of a straight crack in Figure 12(b). This clearly shows that the effective stress intensity factor of the kinked crack is lower than that of a straight crack under the same load, which results in the better dwell cracking resistance for the N-type specimen case.

In the present FEA modeling, the kinked dwell crack is simplified as inclining at a constant angle, while in reality the kinked dwell crack might branch and zag, depending on how the cracked grain boundary aligns at the crack tip. This means in real cases it might be very difficult to predict the local stress intensity factors as the crack tip propagates. The lower effective stress intensity factor is caused by the large deviation of the dwell crack from the pre-crack plane, which is believed to be the main reason for the better dwell cracking resistance of the N- than P-type specimens.

5 Conclusions

Dwell-fatigue crack propagation behaviors of SLM IN718 at 823 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C) under different heat-treatment conditions have been investigated in the present study. The damage mechanism and effects of the grain boundary \(\delta \) and notch orientation on crack propagation rates were compared and discussed. The main conclusions can be summarized as:

-

The main damage mechanism during the dwell-fatigue crack propagation of SLM IN718 at 823 K (550 \(^{\circ }\)C) is creep, while at the same temperature it is the environmentally assisted grain boundary attack for forged IN718. Therefore, SLM IN718 shows inferior dwell-fatigue cracking resistance to the forged counterpart.

-

Grain boundary \(\delta \) inhibits grain boundary sliding and reduces the crack propagation rate in the intergranular fracture regime.

-

In the N-type specimens the columnar grain boundaries mostly deviate at a small angle or even parallel to the loading direction, resulting in a lower effective stress intensity for this kinked crack path. The cracking mechanism is the same in N- and P-type specimens for the same heat-treated condition.

References

Gasser, A., G. Backes, I. Kelbassa, A. Weisheit, and K. Wissenbach: Laser Tech. J., 2010, vol. 7, pp. 58–63.

Chlebus, E., K. Gruber, B. Kuźnicka, J. Kurzac, and T. Kurzynowski: Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2015, vol. 639, pp. 647–55.

Deng, D., R.L. Peng, H. Brodin, and J. Moverare: Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2018, vol. 713, pp. 294–306.

Trosch, T., J. Strößner, R. Völkl, and U. Glatzel: Mater. Lett., 2016, vol. 164, pp. 428–31.

Rickenbacher, L., T. Etter, S. Hövel, and K. Wegener: Rapid Prototyp. J., 2013, vol. 19, pp. 282–90.

Xu, J., H. Gruber, D. Deng, R.L. Peng, and J.J. Moverare: Acta Mater., 2019, vol. 179, pp. 142–57.

Montero-Sistiaga, M.L., S. Pourbabak, J. Van Humbeeck, D. Schryvers, and K. Vanmeensel: Mater. Des., 2019, vol. 165, p. 107598.

Tomus, D., Y. Tian, P.A. Rometsch, M. Heilmaier, and X. Wu: Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2016, vol. 667, pp. 42–53.

Tomus, D., P.A. Rometsch, M. Heilmaier, and X. Wu: Addit. Manuf., 2017, vol. 16, pp. 65–72.

Carter, L.N., C. Martin, P.J. Withers, and M.M. Attallah: J. Alloys Compd., 2014, vol. 615, pp. 338–47.

Messé, O., R. Muñoz-Moreno, T. Illston, S. Baker, and H. Stone: Addit. Manuf., 2018, vol. 22, pp. 394–404.

Wang, X., L.N. Carter, B. Pang, M.M. Attallah, and M.H. Loretto: Acta Mater., 2017, vol. 128, pp. 87–95.

Koutiri, I., E. Pessard, P. Peyre, O. Amlou, and T. De Terris: J. Mater. Process. Technol., 2018, vol. 255, pp. 536–46.

Leary, M., M. Mazur, H. Williams, E. Yang, A. Alghamdi, B. Lozanovski, X. Zhang, D. Shidid, L. Farahbod-Sternahl, G. Witt, et al.: Mater. Des., 2018, vol. 157, pp. 179–99.

Li, H., J. Sun, M. Hardy, H. Evans, S. Williams, T. Doel, and P. Bowen: Acta Mater., 2015, vol. 90, pp. 355–69.

Andersson, H., C. Persson, and T. Hansson: Int. J. Fatigue, 2001, vol. 23, pp. 817–27.

Antunes, F., J. Ferreira, and C. Branco: Mater. High Temp., 2000, vol. 17, pp. 439–48.

Bache, M., W. Evans, and M. Hardy: Int. J. Fatigue, 1999, vol. 21, pp. S69–77.

Gustafsson, D. and E. Lundström: Int. J. Fatigue, 2013, vol. 48, pp. 178–86.

Gustafsson, D., J. Moverare, S. Johansson, K. Simonsson, M. Hörnqvist, T. Månsson, and S. Sjöström: Int. J. Fatigue, 2011, vol. 33, pp. 1461–69.

Gustafsson, D., E. Lundström, and K. Simonsson: Int. J. Fatigue, 2013, vol. 52, pp. 124–30.

Osinkolu, G., G. Onofrio, and M. Marchionni: Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2003, vol. 356, pp. 425–33.

Pedron, J.P. and A. Pineau: Mater. Sci. Eng., 1982, vol. 56, pp. 143–56.

Saarimäki, J., J. Moverare, R. Eriksson, and S. Johansson: Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2014, vol. 612, pp. 398–405.

Saarimäki, J., M.H. Colliander, and J.J. Moverare: Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2017, vol. 692, pp. 174–81.

Krupp, U. and C. McMahon Jr.: J. Alloys Compd., 2004, vol. 378, pp. 79–84.

Bricknell, R. and D. Woodford: Metall. Trans. A, 1981, vol. 12, pp. 1673–80.

Sadananda, K. and P. Shahinian: Metall. Trans. A, 1977, vol. 8, pp. 439–49.

Johnson, H.: Mater. Res. Stand., 1965, vol. 5, pp. 442–45.

Xu, S., X.J. Wu, A. Koul, and J. Dickson: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 1999, vol. 30A, pp. 1039–45.

Gustafsson, D., J. Moverare, S. Johansson, M. Hörnqvist, K. Simonsson, S. Sjöström, and B. Sharifimajda: Procedia Eng., 2010, vol. 2, pp. 1095–1104.

Hayes, R.: Superalloys 718, 625 and Various Derivatives, TMS, 1991, pp. 549–62.

Pröbstle, M., S. Neumeier, J. Hopfenmüller, L. Freund, T. Niendorf, D. Schwarze, and M. Göken: Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2016, vol. 674, pp. 299–307.

Kuo, Y.L., A. Kamigaichi, and K. Kakehi: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2018a, vol. 49A, pp. 3831–37.

Kuo, Y.L., T. Nagahari, and K. Kakehi: Materials, 2018b, vol. 11, p. 996.

Hayes, R.: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2008, vol. 39A, pp. 2596–2606.

Miller, C.F., G.W. Simmons, and R.P. Wei: Scripta Mater., 2000, vol. 42, pp. 227–32.

Boehlert, C., D. Dickmann, and N.N. Eisinger: Metall. Mater. Trans. A, 2006, vol. 37A, pp. 27–40.

M. Chaturvedi and Y. Han: https://doi.org/10.7449/1989/Superalloys_1989_489_498, 1989.

Chen, W. and M. Chaturvedi: Acta mater., 1997, vol. 45, pp. 2735–46.

Han, Y. and M. Chaturvedi: Mater. Sci. Eng., 1987, vol. 89, pp. 25–33.

Kuo, Y.L., S. Horikawa, and K. Kakehi: Scripta Mater., 2017, vol. 129, pp. 74–78.

Chen, W. and M. Chaturvedi: Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 1994, vol. 183, pp. 81–89.

Hyde, T., A. Becker, Y. Song, and W. Sun: Comput. Mater. Sci., 2006, vol. 35, pp. 35–41.

Radhakrishna, C. and K.P. Rao: Mater. High Temp., 1994, vol. 12, pp. 323–27.

Reddy, G.M., C. Murthy, N. Viswanathan, and K.P. Rao: Sci. Technol. Weld. Join., 2007, vol. 12, pp. 106–14.

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Linköping University. This research was sponsored by Siemens AG in Berlin, Germany, who provided selective laser-melted IN718 for this research. Faculty grant SFO-MAT-LiU#2009-00971 at Linköping University, the Chinese Scholarship Council, Agora Materiae and Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems (Vinnova grant 2016-05175) are also acknowledged for their financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Manuscript submitted July 30, 2019.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, D., Eriksson, R., Peng, R.L. et al. On the Dwell-Fatigue Crack Propagation Behavior of a High-Strength Ni-Base Superalloy Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. Metall Mater Trans A 51, 962–972 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-019-05548-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-019-05548-8