Abstract

Summary

An informatics-driven population bone health clinic was implemented to identify, screen, and treat rural US Veterans at risk for osteoporosis. We report the results of our implementation process evaluation which demonstrated BHT to be a feasible telehealth model for delivering preventative osteoporosis services in this setting.

Purpose

An established and growing quality gap in osteoporosis evaluation and treatment of at-risk patients has yet to be met with corresponding clinical care models addressing osteoporosis primary prevention. The rural bone health tea m (BHT) was implemented to identify, screen, and treat rural Veterans lacking evidence of bone health care and we conducted a process evaluation to understand BHT implementation feasibility.

Methods

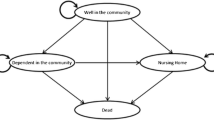

For this evaluation, we defined the primary outcome as the number of Veterans evaluated with DXA and a secondary outcome as the number of Veterans who initiated prescription therapy to reduce fracture risk. Outcomes were measured over a 15-month period and analyzed descriptively. Qualitative data to understand successful implementation were collected concurrently by conducting interviews with clinical personnel interacting with BHT and BHT staff and observations of BHT implementation processes at three site visits using the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework.

Results

Of 4500 at-risk, rural Veterans offered osteoporosis screening, 1081 (24%) completed screening, and of these, 37% had normal bone density, 48% osteopenia, and 15% osteoporosis. Among Veterans with pharmacotherapy indications, 90% initiated therapy. Qualitative analyses identified barriers of rural geography, rural population characteristics, and the infrastructural resource requirement. Data infrastructure, evidence base for care delivery, stakeholder buy-in, formal and informal facilitator engagement, and focus on teamwork were identified as facilitators of implementation success.

Conclusion

The BHT is a feasible population telehealth model for delivering preventative osteoporosis care to rural Veterans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

07 April 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-021-00916-7

References

Williams ST et al (2017) A comparison of electronic and manual fracture risk assessment tools in screening elderly male US veterans at risk for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 28(11):3107–3111

Khosla S et al (2016) Addressing the crisis in the treatment of osteoporosis: a path forward. J Bone Miner Res 32(3):424–430

Force, U.S.P.S.T (2011) Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 154(5):356–364

Cosman F et al (2014) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25(10):2359–2381

Lim LS et al (2009) Screening for osteoporosis in the adult U.S. population: ACPM position statement on preventive practice. Am J Prev Med 36(4):366–375

Watts NB et al (2012) Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97(6):1802–1822

Otmar R et al (2012) General medical practitioners’ knowledge and beliefs about osteoporosis and its investigation and management. Arch Osteoporos 7:107–114

Salminen H, Piispanen P, Toth-Pal E (2019) Primary care physicians’ views on osteoporosis management: a qualitative study. Arch Osteoporos 14(1):48

Antonelli M, Einstadter D, Magrey M (2014) Screening and treatment of osteoporosis after hip fracture: comparison of sex and race. J Clin Densitom 17(4):479–483

Lewiecki E et al (2018) Hip fracture trends in the United States, 2002 to 2015. Osteopororis Int 29:712–722

Solimeo SL et al Factors associated with osteoporosis care of men hospitalized for hip fracture: a retrospective cohort study. J Bone Miner Res Plus In Press

Lawrence PT et al (2017) The Bone Health Team: a team -based approach to improving osteoporosis care for primary care patients. J Prim Care Community Health 8(3):135–140

Kanis JA, Melton LJ 3rd, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N (1994) The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 9(8):1137–1141

Kanis JA et al (2010) Development and use of FRAX in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 21(Suppl 2(Journal Article)):S407–S413

Ja K et al (2010) The effects of a FRAX (R) revision for the USA. Osteoporos Int 21:35–40

Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. 1.15.2020]; Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural - urban-commuting-are a-code s.aspx# .U9lO7GPDWHo

van der Velde RY et al (2017) Effect of implementation of guidelines on assessment and diagnosis of vertebral fractures in patients older than 50 years with a recent non -vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 28(10):3017–3022

Diem SJ et al (2017) Screening for osteoporosis in older men: operating characteristics of propose d strategies for selecting men for BMD testing. JGIM 32:1235–1241

Adler RA, Tran MT, Petkov VI (2003) Performance of the osteoporosis self-assessment screening tool for osteoporosis in American men. Mayo Clin Proc 78(6):723–727

Richards JS et al (2014) Validation of the osteoporosis self-assessment tool in US male veterans. J Clin Densitom 17(1):32–37

Nayak S et al (2015) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the performance of clinical risk assessment instruments for screening for osteoporosis or low bone density. Osteopororis Int 26(5):1543–1154

Stetler CB et al (2011) A guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation. Implement Sci 6(99)

Khosla S (2010) Update in male osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95(1):3–10

Willson T et al (2015) The clinical epidemiology of male osteoporosis: a review of the recent literature. Clin Epidemiol 7:65–76

Solomon DH et al (2007) Improving care of patients at -risk for osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 22(3):362–367

Lafata JE et al (2007) Improving osteoporosis screening: results from a randomized cluster trial. J Gen Intern Med 22(3):346–351

Warriner AH et al (2014) Effect of self-referral on bone mineral den sity testing and osteoporosis treatment. Med Care 52(8):743–750

Rothmann MJ et al (2017) Non-participation in systematic screening for osteoporosis-the ROSE trial. Osteoporos Int 28(12):3389–3399

Miller K, et al. (2017) Cost-effectiveness of a Bone Health Team for Screening and Treating Veterans at Risk for Fragility Fractures, in ASBMR. JBMR Denver, Colorado, USA

Khosla S, Shane E (2016) A crisis in the treatment of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 31(8):1485–1487

Zeldow D, Lewiecki E, Adler R (2017) Hip fractures and declining DXA testing : at a breaking point? Innov Aging 1(1):843

Lewiecki EM et al (2018) Hip fracture trends in the United States, 2002 to 2015. Osteoporos Int 29(3):717–722

Leslie WD, LaBine L, Klassen P, Dreilich D, Caetano PA (2012) Closing the gap in postfracture care at the population level: a randomized controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J 184(3):290–296

Kessous R et al (2014) Improving compliance to osteoporosis workup and treatment in po stmenopausal patients after a distal radius fracture. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 53(2):206–209

Danila M et al (2017) OP0051 The activating patients at risk for osteoporosis study: a randomized trial within the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 76(Suppl 2):72–72

Merle B et al (2017) Post-fracture care: do we need to educate patients rather than doctors? The PREVOST randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 28(5):1549–1558

Majumdar SR et al (2011) Nurse case-manager vs multifaceted intervention to improve quality of osteoporosis care after wrist fracture: randomized controlled pilot study. Osteoporos Int 22(1):223–230

Jaglal SB et al (2012) Impact of a centralized osteoporosis coordinator on post -fracture osteoporosis management: a cluster randomized trial. Osteoporos Int 23(1):87–95

Yates CJ et al (2015) Bridging the osteoporosis treatment gap: performance and cost-effectiveness of a fracture liaison service. J Clin Densitom 18(2):150–156

Solomon DH et al (2006) A randomized controlled trial of mailed osteoporosis education to older adults. Osteoporos Int 17(5):760–767

Solomon DH et al (2007) Osteoporosis improvement: a large-scale randomized controlled trial of patient and primary care physician education. J Bone Miner Res 22(11):1808–1815

Heyworth L et al (2014) Comparison of interactive voice response, patient mailing, and mailed registry to encourage screening for osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 25(5):1519–1526

Martin J et al Interventions to improve osteoporosis care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 31(3):429–446

AAMC (2019) State Physician Workforce Data Report . 2019. AAMC, Washington, DC

NIH (2018) Pathways to Prevention (P2P): appropriate use of drug therapies for osteoporotic fracture prevention.

Acknowledgments

We thank the VA personnel who participated in the qualitative aspects of this study and Anna Lynch, who assisted with research coordination and IRB documentation. This work was supported by the grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Rural Health Veterans Rural Health Resource Center-Iowa City (10707 to SLS) and Salt Lake City (7359 to KM), and by the VA Specialty Care Services Center of Innovation. SL Solimeo and M Steffen receive support from the Center for Comprehensive Access & Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE), Department of Veterans Affairs, Iowa City VA Health Care System, Iowa City, IA (Award # CIN 13-412). SL Solimeo also received support from VA HSR&D (Award # CDA 13-272) [add other funding if need be]. The US Department of Veterans Affairs had no role in the analysis or interpretation of data or the decision to report these data in a peer-reviewed journal. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

An informatics-driven population bone health clinic was implemented to identify, screen, and treat rural US Veterans at risk for osteoporosis. We report the results of our implementation process evaluation which demonstrated BHT to be a feasible telehealth model for delivering preventative osteoporosis services in this setting.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Rural Health Veterans Rural Health Resource Center-Iowa City (10707 to SLS) and Salt Lake City (7359 to KM). SL Solimeo and M Steffen receive support from the Center for Comprehensive Access & Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE), Department of Veterans Affairs, Iowa City VA Health Care System, Iowa City, IA (Award # CIN 13-412). SL Solimeo also receives support from VA HSR&D (Award # CDA 13-272). The US Department of Veterans Affairs had no role in the analysis or interpretation of data or the decision to report these data in a peer-reviewed journal. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KM drafted the manuscript. SLS designed the study and contributed to qualitative data analysis. SW contributed to qualitative data collection and literature review. ATS and MJS contributed to the qualitative data collection, analysis, and writing. ZLA, KDM, and SP contributed to the clinical informatics operations of BHT and quantitative data collection. KM, JG, and GC contributed to the quantitative analysis and reporting on the BHT clinical model. All named authors have made substantive contributions to manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access cancellation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, K.L., Steffen, M.J., McCoy, K.D. et al. Delivering fracture prevention services to rural US veterans through telemedicine: a process evaluation. Arch Osteoporos 16, 27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-021-00882-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-021-00882-0