Abstract

Background

Since 2017, women have made up over 50% of medical school matriculants; however, only 16% of department chairs are women—a number that has remained stagnant and demonstrates the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions in medicine.

Objective

To better understand the challenges women face in leadership positions and to inform how best to advance women leaders in Hospital Medicine.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Using hermeneutical phenomenological methods, we performed semi-structured qualitative interviews of ten female division heads from hospital medicine groups in the USA, transcribed verbatim, and coded for thematic saturation using Atlas.ti software.

Measurements

Qualitative themes and subthemes.

Key Results

Ten women hospitalist leaders were interviewed from September through November 2019. Participants identified four key challenges in their leadership journeys: lack of support to pursue leadership training, bullying, a sense of sacrifice in order to achieve balance, and the need for internal and external validation. Participants also suggested key interventions in order to support women leaders in the future: recommending a platform to share experiences, combat bullying, advocate for themselves, and bolster each other in sponsorship and mentorship roles. Finally, participants identified how they have unique strengths as women in leadership, and are transforming the culture of medicine with a focus on diversity and flexibility.

Conclusion

Women in leadership positions face unique challenges, but also have a unique perspective as to how to support the next generation of leaders.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Since 2017, women have made up over 50% of medical school matriculants;1, 2 however, only 35% of active physicians and 16% of department chairs are women, including a similar proportion within Hospital Medicine (16%).3 This number has remained stagnant and demonstrates the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions in medicine.4, 5 The leaky pipeline contributes to the gender pay gap, lack of diversity in decision-making roles, and inflexible workplace culture.6, 7 In the relatively younger field of Hospital Medicine, women comprise 47% of the workforce; however, the inequities in leadership attainment and success in scholarly productivity persist.3, 7, 8

Prior work has identified structural, personal, and cultural challenges that prevent women from achieving leadership positions.9, 10 Structural challenges include inflexibility in the workplace resulting in work-family conflict, which is more likely to impact women, and evidence that women need to achieve a higher threshold for accomplishments, such as grant funding, before they successfully attain leadership positions as compared to men.10, 11 Some studies suggest that women do not apply for leadership positions or avoid seeking promotions because of perceived work-life conflict.12, 13 Finally, there are gendered social influences in place that impact the stereotype of a successful leader, typically aligning with a male figure. However, research also shows that women are equally as effective leaders and are more likely to adopt the typically more successful collaborative approach.14,15,16 Despite a stereotype that women are less skilled at negotiating, studies refute this and show that women are equally as skilled, particularly when advocating on behalf of others.17

We sought to better understand the challenges women hospitalists face in attainment of leadership positions, the challenges they face in their current roles, and the value that they bring when in these positions, with the goal of informing how best to advance future women leaders in Hospital Medicine.

METHODS

Study Design

This study used a hermeneutic phenomenology methodology, which applies context to the exploration of a lived experience,18and was chosen because it recognizes the importance of context (e.g., gender) to fully characterize participant’s experiences. We recognized that the personal experiences of some research team members as female physicians influenced interpretation efforts, and this methodology allowed discussion to enhance the ability to interpret participants’ narratives. The “Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ)” was used to guide the structure and reporting of the qualitative study results.19

Setting and Participants

After receiving approval from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, we recruited participants using information from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) chapter membership website to identify academic and community institutions with active groups across the country. In total, we identified 131 programs and from this list, we used publicly available institutional websites to identify female division or group heads within these institutions and obtain their contact information. We identified 22 women leaders; the remainder were either men or not identified. Each of these individuals was invited via electronic communication to participate in this study, and 9 agreed to participate. A purposeful snowball approach was used to seek their recommendations for women in other targeted programs, and with this approach, we identified two other women leaders who consented to participate. All participants provided informed consent.

Data Collection

All data were collected through 40- to 60-min semi-structured interviews between September and November 2019. Demographics such as race, ethnicity, leadership role, number of years in their current position, and institution name were also collected. We terminated data collection after 10 interviews when no new ideas emerged.

The semi-structured interview guide included five domains designed to explore the leadership journey and experiences based off of prior qualitative work of women in leadership.9 Participants were asked about (1) their path into their current leadership position, (2) challenges they experienced both personally and professionally, (3) lessons they learned through their leadership experiences, (4) benefits they perceived both personally and for their institution, and (5) possible interventions to improve the trajectory for the next generation of women leaders.

Interviews were conducted by investigators EG and AY. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by study team member KJ, a practicing nurse. Identifying information was removed during the transcription process prior to analysis by the larger team.

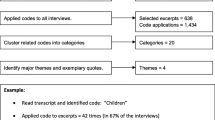

Analysis

Interviews were coded by four members of the study team (EG, AY, KJ, and LM, a research data analyst with experience in qualitative research) using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach. Codes were applied and further analyzed using Atlas.ti software version 8.4.15 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). All transcripts were coded by a minimum of three study team members, with code disparities reconciled by team consensus. Coding was completed in-person and emergent themes and subthemes were then identified by all members of the study team. Thematic saturation was achieved when no new themes emerged for two interviews. Member checking was performed after analysis was completed.

RESULTS

Using the sampling method, we identified eleven female leaders across the nation who agreed to participate. Of the eleven who agreed to participate, ten participants completed the semi-structured interview with one unable to participate due to scheduling conflicts. The participants represented programs in the East Coast (5), Mountain West (4), and West Coast (1) and represented diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. The major themes generated by the participants from the five interview question domains were grouped by (1) challenges experienced, (2) interventions and recommendations, and (3) transforming culture.

Challenges Experienced

Participants identified a range of challenges faced in their leadership journeys across four domains—lack of support to acquire leadership training and exposure, bullying in the workplace, combating a sense of sacrifice, and the need for internal and external validation.

First, participants described a perceived lack of support to acquire leadership training due to misperceptions of both personal and professional goals. While opportunities for training were regularly offered to male group members, women had to be more proactive due to assumptions regarding personal obligations associated with being a woman, including that they would “just get pregnant again.”

And my boss and the boss above wanted to meet with me because of all the great work we had done, and they said what can we do for you? And I said I would love to go to (a training course) and they both stopped and kind of looked at me surprised. And I said you know I know your assumption is that I’m going to get pregnant again but not all women are just going to go ahead and do that. And I probably shouldn’t have been so forthright but it kind of stopped them and they said oh my gosh okay. (Participant 7)

The second challenge women described was bullying in the workplace in the form of inappropriate behavior or antagonistic actions by both men and women, perceived as microaggressions, and the lack of support from other women.

Two men who were junior to me who made it pretty clear in lots of subtle ways that they were not so happy to have me as a leader. And that was…you know a learning journey for me, whether it was chewing gum during a meeting with me or other sort of casual behaviors that you normally wouldn’t exhibit in a meeting with a leader you know, to asking if the office meeting would be in his office or my office again typically one would assume the meeting would be in your leader’s office. (Participant 10)

I still believe that women can be our worse enemies… we are very good at building each other but we are also very quick to bring each other down. So, I think being more supportive to our fellow female members, especially in situations where we are the minority would go a long way rather than just knit picking and seeing the faults in people and bringing each other down. Because I think when people see that, it is very easy for people to say oh they are just being catty women. So, I think we need to be cognizant of that behavior and try to foster each other’s growth and be supportive in that realm. (Participant 2)

The third challenge participants described was a pervasive sense of sacrifice in order to achieve a desired level of balance in both their personal and professional life. This pertained to balancing work with home responsibilities, acknowledging that women largely do more of the household duties (“I often say, I wish I had a wife”) as well as balancing different domains within their profession, including administrative and clinical duties. This sense of sacrifice led to feelings of burnout and inadequacy.

The work life integration in particular because while in this day in age men do help, it is still overwhelmingly that the woman manages the home. Even though you delegate things to your husband, you still have to figure out what needs to be delegated. This is a challenge no matter how helpful your husband is. Generally speaking, women still manage the home. I can’t tell you how many times in my career early on I would joking say (but I half meant it) I wish I had a wife (Participant 1)

You know you don’t feel like a good doctor clinically and you don’t feel like a good leader administratively and then trying to be a wife and be a mother and run a household…do all of those things. There have been times over this last year where I have felt burnout kind of globally. And I feel that has been difficult at the end of the day where I don’t feel I’ve been the best at any of those things and that is pretty hard to take. (Participant 8)

Finally, women described a need to validate their contributions in their leadership role, externally to others within the healthcare profession, and internally to themselves, battling the “imposter syndrome.” The external validation was perceived as a need to prove themselves by taking on additional tasks because women are not given “the benefit of the doubt.”

I’ll tell you why you have to prove yourself as a woman in leadership. Men for example, it is easier for them, and maybe this is a stereotype, to bond over golf, basketball, sailing or whatever…meeting after hours, things like that. But for a woman, even 5:30 is a difficult meeting for me to make because I want to go home and spend time with my (kids). And so, when you’re engaging with people frequently, they get to know you, they get to know who you are, they get to know your capabilities . . . So, men you form this connection outside the workplace, so they know your capabilities. But for a woman if you’re not able to be in these spaces, you have to prove yourself a little bit more…. If I can’t make it to 8/10 5:30 pm meetings, then I have to figure out how to engage in different ways…it might be that I say yes to this project so people know what I can do….So, when you are at these events that happen after hours, you are hanging out with the dean and I am not. . . If a project or opportunity comes along then you have these people you are interacting with frequently then yes you take it, so people know who you are. (Participant 1)

Internally, women described a sense of departing from their natural leadership style in order to be perceived as more effective or worrying that assuming the normative stereotype of male leadership would be interpreted negatively. Participants described spending emotional energy “self-regulating” and second-guessing.

I am this small girl sometimes I feel that way and I feel like I just have to be more firm than is really truly in my character to be taken as seriously as someone who doesn’t really have to exert much effort. (Participant 2)

I do think there is some truth to like a man’s emotions can run high and he is considered serious and passionate versus when a woman’s emotions run high people will have a knee jerk reaction and say calm down (Participant 6)

For each of these challenges, the participants were sometimes hesitant to attribute their experience to gender, instead stating, “I think it’s just about who I am.”

Interventions and Recommendations

Each of the participants offered recommendations to better prepare the next generation of women in leadership positions. The overarching theme was a need for women to share their experiences with each other in order to create a support network, advocate for each other, and offer role modeling and sponsorship.

So just to realize that I was not alone in the challenges we face not only in hospital medicine but in leadership, family, time of life, everything. I think that was really powerful to feel some additional advocates on my side. (Participant 8)

I think the first being obviously having those goal role models. So, think for a lot of younger female physicians, seeing me in this role is very powerful for them and they see that people can do it. I think there has been a change from a very old school physician. (Participant 3)

Women wanted more training in self-advocacy, as well as how to stand up to bullying in the workplace, and in how to battle stereotypical female habits, such as not taking credit for their contributions.

I think having more avenues for females in leadership and learning to advocate more for yourself because I think that is sometime to this day that I am not a good advocator for myself in certain ways especially from a financial standpoint. I think just knowing what you want and not being afraid of rejection. (Participant 8)

I think also changing the culture of what is acceptable behavior and I think giving people the tools so that when people walk into situations like these things to have sort of language to cope with it. (Participant 10)

Finally, women described a need to change the structure of medicine, such as expectation of the normal leadership trajectory, which may not apply for women, who are often balancing child-rearing of young children earlier in their career (“You don’t have to do it all in your 30s”).

Transforming Culture

Despite the challenges faced, women described pursuing leadership positions because of the unique benefits that they contribute, such as serving in a nurturing, caregiving role for their group members, and serving the greater good. They also reported a motivation to attract a more diverse workforce by incorporating and valuing flexibility (Table 1). Ultimately, participants describe an evolution of the culture of medicine by valuing diversity and flexibility, ultimately benefiting institutions, individuals, and the leaders themselves.

DISCUSSION

The important finding of this study is that women in leadership within Hospital Medicine experience unique challenges during their leadership journey and, as a result, are a valuable resource in identifying how we can transform our culture in medicine to augment a more diverse workforce and leadership prototype. Our participants described these challenges in language that brought forth the gender stereotypes that are embedded within our medical culture, such as lack of sponsorship, inappropriate behavior directed towards them, a need for validation, and the stresses associated with work-life balance. Women felt that they brought unique skills to their roles such as a collaborative model of leading, an altruistic sense of purpose, and a focus on the well-being of their group, oftentimes resulting in flexible work models to support each members’ needs.

Our participants also described a time of transformation, evolving to a new, all-inclusive culture. Leaders are no longer accepting that “the job description inherently set us up to fail,” and are instead rewriting the job description. Current leaders are battling this tension, between “doing the job like a man does” and finding the unique ways that women can add value. Women are increasingly feeling the mission to be in a position of sponsorship for others, recognizing that they need to create forums for addressing unique experiences faced by women across the continuum of training, starting in medical school. While participants highlighted the engendered male model of leadership that exists, they also hesitated to attribute their experiences to gender, instead stating, “I think it’s just about who I am.” This echoes prior work that women attempt to erase gender inequality as a contributing factor to individual experiences, perhaps not wanting to attribute successes to gender.20

As a result of these findings, the field of hospital medicine ought to consider the recommendations offered in this study to further accelerate culture transformation. Prior work has highlighted the importance of the climate for women faculty in the advancement of women in leadership, as well as prioritizing the promotion, retention, and mentoring of women.12, 21 Our work supports this—each of our participants recommended creation of a forum to share experiences and create sponsorship opportunities. It is also necessary to create structure and processes to support a more diverse leadership team. Prior work has shown that changing the process by which conference speakers are chosen has eliminated gender disparities in speakership—our participants suggested similar structural changes, such as flexibility in the workplace.22 Building these structures and processes within hospital medicine to better support diversified leadership warrants further exploration. Finally, it is important to understand and learn from the experiences of women in leadership in other specialties, an area of future exploration.

A limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size; however, this represents a meaningful percentage of the total number of women in hospital medicine leadership; also, thematic saturation was achieved, suggesting that additional interviews would not have altered the findings. Our study also brings several strengths. The use of qualitative interviews allowed us to explore nuances of the experience of the participants in greater depth, and the use of snowball methodology allowed us to identify a more diverse set of leaders who were not otherwise identifiable through searchable online content.

Our study highlights that the challenges women face are not unique to junior faculty but are pervasive throughout a woman’s career. Our interviewees bring a wealth of experiences and their perspectives have highlighted future areas of focus in order to change the culture. In conclusion, women in leadership positions within hospital medicine face unique challenges, but also have a unique perspective as to how to support the next generation of leaders within a field where there is gender balance, yet persistent disparities.

References

2018 Fall Applicant and Matriculant Data Tables, Association of American Medical Colleges, 2018. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/d/1/92-applicant_and_matriculant_data_tables.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2020.

ACGME Residents and Fellows by Sex and Specialty, 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges, 2017. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/acgme-residents-and-fellows-sex-and-specialty-2017.

Burden, M, Frank, MG, Keniston, A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med 2015;10:481-485.

Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges, 2017. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2017. Accessed May 1, 2020.

Association of American Medical Colleges Faculty Roster, December 31, 2017 snapshot, as of December 31, 2018. Department Chairs by Department, Sex, and Race/Ethnicity, 2017. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/reports/1/supplementaltablec.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2020.

Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294–1304.

Association of American Medical Colleges Faculty Salary Survey, April, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-09/aamcfacultysalarydata-md.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2020.

Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27.

Bismark M, Morris J, Thomas L, Loh E, Phelps G, Dickinson H. Reasons and remedies for under-representation of women in medical leadership roles: a qualitative study from Australia. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e009384.

Gottenborg E, Maw A, Ngov LK, Burden M, Ponomaryova A, Jones CD. You can’t have it all: the experience of academic hospitalists during pregnancy, parental leave, and return to work. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):836-839.

Beeler WH, Griffith KA, Jones RD, et al. Gender, professional experiences, and personal characteristics of academic radiation oncology chairs: data to inform the pipeline for the 21st century. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;104(5):979-986.

Carapinha R, McCracken CM, Warner ET, Hill EV, Reede JY. Organizational context and female faculty’s perception of the climate for women in academic medicine. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(5):549-559.

Roth VR, Theriault A, Clement C, Worthington J. Women physicians as healthcare leaders: a qualitative study. J Health Organ Manag. 2016;30(4):648-665.

Eagly AH, Johannesen-Schmidt MC, van Engen, Marloes L. Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: a meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(4):569–91.

Rosser VJ. Faculty and staff members perceptions of effective leadership: are there differences between men and women leaders? Equity Excellence Education. 2003;36(1):71–81.

Eagly AH, Johnson BT. Gender and leadership style: a meta analysis. Psychol Bull. 1990;108(2):233–56.

Mazei J, Hüffmeier J, Freund PA, Stuhlmacher AF, Bilke L, Hertel G. A meta-analysis on gender differences in negotiation outcomes and their moderators. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(1):85-104.

Lopez KA, Willis DG. Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:726-35

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups, International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19(6): 349-357

Webster F, Rice K, Christian J, et al. The erasure of gender in academic surgery: a qualitative study. The American Journal of Surgery. 2016;212(4):559-565.

Carr PL, Gunn C, Raj A, Kaplan S, Freund KM. Recruitment, promotion, and retention of women in academic medicine: how institutions are addressing gender disparities. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(3):374–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2016.11.003

Northcutt N, Papp S, Keniston A, et al. SPEAKers at the National Society of Hospital Medicine Meeting: a follow-UP study of gender equity for conference speakers from 2015 to 2019. The SPEAK UP Study. J Hosp Med. 2020;4:228-231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gottenborg, E.W., Yu, A., McBeth, L.J. et al. The Experience of Women in Hospital Medicine Leadership: a Qualitative Study. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 2678–2682 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06458-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06458-x