Abstract

Background

Several policymakers have suggested that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has fueled the opioid epidemic by subsidizing opioid pain medications. These claims have supported numerous efforts to repeal the ACA.

Objective

To determine the effect of the ACA’s young adult dependent coverage insurance expansion on emergency department (ED) encounters and out-of-hospital deaths from opioid overdose.

Design

Difference-in-differences analyses comparing ED encounters and out-of-hospital deaths before (2009) and after (2011–2013) the ACA young adult dependent coverage expansion. We further stratified by prescription opioid, non-prescription opioid, and methadone overdoses.

Participants

Adults aged 23–25 years old and 27–29 years old who presented to the ED or died prior to reaching the hospital from opioid overdose.

Main Measures

Rate of ED encounters and deaths for opioid overdose per 100,000 U.S. adults.

Key Results

There were 108,253 ED encounters from opioid overdose in total. The expansion was not associated with a significant change in the ED encounter rates for opioid overdoses of all types (2.04 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 0.75 to 4.82]), prescription opioids (0.60 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 1.98 to 0.77]), or methadone (0.29 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 0.78 to 0.21]). There was a slight increase in the rate of non-prescription opioid overdoses (1.91 per 100,000 adults [95% CI 0.13–3.71]). The expansion was not associated with a significant change in the out-of-hospital mortality rates for opioid overdoses of all types (0.49 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 0.80 to 1.78]).

Conclusions

Our findings do not support claims that the ACA has fueled the prescription opioid epidemic. However, the expansion was associated with an increase in the rate of ED encounters for non-prescription opioid overdoses such as heroin, although almost all were non-fatal. Future research is warranted to understand the role of private insurance in providing access to treatment in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

In the midst of the current opioid overdose epidemic, several policymakers have suggested that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has fueled the crisis of both prescription and illicit opioid misuse. The stated concern is that the ACA’s expanded insurance coverage increased access to physicians who prescribe opioids and reimbursement of opioid prescription fills, thereby increasing the supply and diversion of opioids, increasing overdoses, and/or transition to opioid use disorder.1 These claims have supported numerous efforts to repeal the ACA.2

Beginning September 23, 2010, the ACA required that all private insurance plans increase the age that children are eligible to stay on their parent’s insurance plan, known as dependent coverage, from age 19 to 26 -years -old. As a result, insurance coverage among young adults aged 19–25 -years -old increased by an estimated 3–5 percentage points.3,4,5 While there is a lack of evidence to support the claim that the young adult dependent coverage insurance expansion contributed to the opioid epidemic, there is evidence that the expansion of private insurance coverage was associated with increased access to treatment of behavioral health disorders, including substance use disorder.6,7,8,9,10,11 This supports the competing hypothesis that private insurance expansion could contribute to a reduction in opioid overdoses through increased access to addiction treatment. Furthermore, evidence from Medicaid beneficiaries suggests that Medicaid expansion did not lead to an increase in opioid overdoses.12,13,14 However, to our knowledge, no study has examined the impact of the ACA’s young adult dependent coverage expansion of private insurance on opioid overdoses. This is important for determining implications of efforts to repeal the ACA in the midst of the opioid overdose crisis.

To fill this knowledge gap, we used the largest national dataset on emergency department (ED) encounters to test the hypothesis that the ACA’s young adult dependent coverage expansion was associated with an increase in opioid overdoses. Secondly, we also used national death certificate data to test the hypothesis that the ACA’s young adult dependent coverage expansion increased opioid-related death rates, thereby also capturing deaths that occurred outside of the hospital. For both analyses, we stratified by opioid type (prescription opioid, non-prescription or illicit opioid, and methadone) to tease out potential mechanisms of contribution to the epidemic.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We studied the effects of the ACA young adult dependent coverage insurance expansion on opioid overdoses treated in the ED and opioid-related deaths using difference-in-differences analyses.15 Our difference-in-differences framework compares opioid overdoses treated in the ED and opioid-related deaths before (2009) and after (2011–2013) the implementation of the dependent coverage expansion in young adults aged 23–25 -years- old to a control group of slightly older adults aged 27–29- years- old who were not eligible for coverage under the expansion. Since the expansion was implemented in September 2010, we excluded 2010 from our analysis because it was difficult to determine if it was “pre-” or “post-” policy phase. We used data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS), a portion of a larger family of databases from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).16 The NEDS is a 20% stratified sample of 945 hospitals in 33 states and the District of Columbia. Unweighted, it comprises approximately 30 million ED encounters each year and weighted, it has nearly 135 million ED encounters. In this study, we used the weighted ED encounters to allow us to make national estimates for the entire U.S. population. We used the Center for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) database, based on county-level death certificates for U.S. residents, to capture outside of hospital deaths as a result of opioid overdose.17 This study was determined to be exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Population

We identified ED encounters in the NEDS in 2009 and 2011–2013 with International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes for non-prescription, prescription, and methadone opioid overdose (965.00–965.02, 965.09)18 in young (aged 23–25 -years- old) and slightly older adults (aged 27–29 -years -old). We selected 23–25-year-old adults because, prior to the dependent coverage expansion in 2010, they were less likely to have access to their parent’s insurance as compared with younger age groups. We selected 27–29-year-old adults as the control group because it is consistent with prior studies.19,20,21 We omitted 26-year-old adults from our analysis because it was difficult to categorize them in either the treatment or control group without access to their birthdate. In the study period, there were 23,814 encounters. After applying sample weights, there were 108,253 encounters in total. In the CDC WONDER database, we identified accidental deaths, within the same time frame and age range, with International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes for non-prescription and prescription opioid, as well as methadone overdoses (T40.0-T40.4).22

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the rate of ED encounters for opioid overdose per 100,000 adults of the same age in the U.S. population. The secondary outcome was the rate of opioid-related deaths per 100,000 adults of the same age in the U.S. population. To analyze the rate of ED opioid overdoses, the numerator was the total number of ED encounters for opioid overdose for a given age and year-quarter. The numerator for the rate of opioid-related deaths was the total number of opioid-related deaths for a given age and year. We used yearly data because the CDC WONDER database does not provide quarterly data. The numerator for the rate of opioid overdoses by insurance type was the total number of ED encounters for opioid overdose by a given insurance type: private, uninsured, or Medicaid, for a given age and year-quarter. We divided each of these numbers by the total number of adults of that same age within that year according to the U.S. Census Bureau population data.23 All of these rates were per 100,000 U.S. adults.

Independent Variables

We extracted primary payer: self-pay/uninsured, no charge, Medicaid, Medicare, private, and other. We used ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes to differentiate prescription and non-prescription opioids, as well as methadone.18 Other clinical and demographic variables we obtained were age, sex, hospital region, median household income by patient residential zip code, and ED disposition. We grouped disposition as follows: treated and released from the ED, admitted as an inpatient, transferred, died in the ED, and unknown.

Statistical Analysis

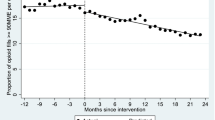

We used difference-in-differences modeling to evaluate the effect of the ACA’s young adult dependent coverage expansion on ED encounters and deaths as a result of opioid overdose and further stratified by prescription, non-prescription, and methadone. This model compares the average change in an outcome before policy implementation to afterward in both treatment and control groups. This approach enables us to isolate the effect of coverage expansion on overdose from other factors that may affect the outcomes of both the treatment and control groups. The treatment group is young adults aged 23–25- years- old and the control group, unaffected by policy enactment, is slightly older adults aged 27–29 -years- old. A major assumption of this approach is that the trends in both the treatment and control groups would have been the same had the policy not occurred. To evaluate this, we tested whether trends were parallel prior to policy enactment. We tested this assumption in Figure 1. The pre-policy period is 2009 and post-policy period is 2011–2013 by year-quarter. We developed a linear regression model as follows:

In this model, Yage, t represents the primary outcome for the group “age” and at time t, β0 is the constant, and Ageage is a dummy variable for the age group. The dummy variable Postt is equal to 1 after the dependent coverage expansion was implemented, 0 before. The interaction term gives the coefficient of interest, which denotes the average impact of the policy on the outcome before versus after implementation in the treatment (23–25-year-olds) compared with the control (27–29-year-olds) groups. Study analysis was completed using STATA Version 14.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Subjects

The demographic and clinical characteristics of both control and treatment groups are depicted in Table 1. During the study period (2009 and 2011–2013), there was a mean of 27,063 ED encounters for all types of opioid overdoses per year. There were 56,063 ED encounters in the treatment group and 52,189 encounters in the control group. Overall, most ED opioid overdoses were men (56.5%). Among types of insurance, 38.7% did not have any insurance, 26.4% had Medicaid, and 24.6% had private insurance. Most overdoses were a result of prescription opioids (56.2%). The vast majority of patients were treated and released from the ED (58.9%) and only 0.2% died during their ED encounter.

Main Results

The mean year-quarter ED encounter rate for opioid overdoses per 100,000 adults was 26.9 (95% CI 25.7–28.0) for the treatment group and 25.8 (95% CI 24.8–26.8) for the control group in our study period. We plotted the rate of ED encounters for overdose of prescription, non-prescription, methadone, and all types of opioids. Figure 1 depicts the trends in the rate of ED encounters for opioid overdoses per 100,000 adults in both age groups before and after the ACA’s young adult dependent coverage expansion. Prior to the expansion, the initial trends between both treatment and control groups appear similar. Yet in the quarter immediately prior to 2010, they appear to separate. Following the ACA, rates for opioid overdose appear to increase in both groups. We further stratified our results by opioid type to determine if the ACA’s young adult dependent coverage expansion resulted in greater access to prescription opioids and therefore more prescription and non-prescription overdoses. The trends in non-prescription opioids initially appear similar but in the 4th quarter of 2009 seem to separate. In prescription opioids, trends appear fairly similar in both groups. The trends in methadone overdoses initially appear dissimilar yet eventually appear to converge.

The main study results are depicted in Table 2. Each row displays the difference-in-differences (DID) estimator for prescription, non-prescription, methadone, and all types of opioids. In 2009, the mean year-quarter ED encounter rate for all types of opioid overdoses was 22.14 per 100,000 adults in the treatment group. After the implementation of the dependent coverage expansion, there was no significant change in the year-quarter ED opioid overdose encounter rate (2.04 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 0.75 to 4.82]) when compared with the control group.

After stratifying by opioid type, there was no significant change in the rate of overdoses from prescription opioids (0.60 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 1.98 to 0.77]), or methadone (0.29 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 0.78 to 0.21]). However, there was a slight increase in the rate non-prescription opioid overdoses of 1.92 per 100,000 adults (95% CI 0.13 to 3.71) when compared with the control group. This is equivalent to 259 (95% CI 18 to 500) more non-prescription opioid overdoses in 2013.

Table 3 depicts the DID estimator for deaths from opioid overdose. Overall, there was no significant change in the rate of opioid-related deaths following the dependent coverage expansion (0.49 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 0.80 to 1.78]). After stratifying by opioid type, there was also no significant change in death rates from prescription opioids (0.25 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 0.48 to 0.97]), non-prescription opioids (0.51 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 0.48 to 0.97]), and methadone (− 0.27 per 100,000 adults [95% CI − 0.72 to 1.75]).

DISCUSSION

A claim proposed by some policymakers is that the ACA has given individuals expanded access to opioid pain medication thereby contributing to the opioid overdose epidemic.1 Our findings do not support this. In this study, we provided new evidence that the implementation of the young adult dependent coverage insurance expansion of the Affordable Care Act in September 2010 was not associated with a change in the overall rates of opioid overdose ED encounters or deaths in the following years of 2011–2013. These findings are in line with a prior study analyzing the effects of early Medicaid expansion, which was shown to actually decrease the rate of overdoses relative to control states.12

When we analyzed the association of the dependent coverage and the types of opioid overdose, we did find that there were approximately 259 more ED encounters for non-prescription opioid overdoses such as heroin, accounting for less than 0.02% of the 14,475 overdoses treated in U.S. EDs in 2013 in our control group of 27–29-year-olds. Furthermore, 99% of these encounters were non-fatal. Potential explanations are that the insurance expansion occurred at the same time as the oxycontin reformulation in 2012 which led to a transition from prescription opioid misuse to heroin use.24 We suspect a small portion of those exposed to prescription opioid pain medications may have developed an addiction, but then transitioned quickly to heroin during this period.25,26,27,28,29 On the other hand, we did not find any association between the young adult insurance expansion with fatal prescription, non-prescription, heroin, or methadone overdoses, nor ED encounters for overdose from prescription opioids and methadone.

While our work and others do not support any claims of significant harm from insurance expansion with regard to the opioid epidemic, there is ample evidence of benefit with regard to increased health insurance coverage among uninsured young adults suffering from substance use disorders and decreased out-of-pocket spending on substance use treatment.9, 30,31,32,33

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, this is an observational study and while our quasi-experimental design was chosen to minimize the effects of unobserved confounding, we cannot rule out the possibility that there were unobserved confounders that affected the propensity of those aged 27–29-year-olds to suffer an opioid overdose more or less than those who were 23–25-year-olds during this time period. Second, to be eligible for the Affordable Care Act’s dependent coverage expansion, one must be under the age of 26 and have parents who are privately insured. All of the individuals in our treatment group were young and likely of higher socio-economic status. As a result, our treatment group is relatively younger and of higher socio-economic status as compared with the entire U.S. population. Furthermore, while opioid overdoses could occur by exposure to prescription opioids by gaining insurance, of those who have misused prescription opioids, most obtained diverted pills from family or friends.34 Therefore, this analysis cannot rule out spillover effects of a potentially increased opioid supply in the community diverted from those who may have obtained them by gaining private insurance to others outside the studied age groups. Thus, these results are only generalizable to the effects of this policy.

Third, although the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Act was implemented to establish some degree of equity in behavioral health benefits offered by insurance plans, variability in coverage for substance use treatment still exists.30, 33 We also recognize there are multiple steps individuals from the treatment group must complete before receiving treatment including the following: perceived need for substance use treatment, a private insurance plan with treatment benefits, and utilization and adherence to treatment. With the study datasets, we are not able to directly observe receipt of opioid prescriptions or substance use treatment. In this study, we only examined the effects of the policy within a few years after it was implemented based on data available at the start of the study. As a result, there may be a lag in the effect of the policy due to the time it takes to develop a substance use disorder. More research with additional years of data is needed to determine the long-term effects of this policy. Finally, previous literature has shown that individuals are more likely to seek medical care as they gain health insurance.35, 36 This may lead to underreporting prior to the ACA, as uninsured individuals suffering from opioid overdose may have been less likely to seek emergency medical care. However, there is no reason to believe that the rate of underreporting would be any different among 23–25-year-old vs. 27–29-year-old patients without insurance prior to ACA implementation.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we performed quasi-experimental difference-in-differences analyses to determine the association of the Affordable Care Act’s young adult dependent coverage expansion with emergency department encounters for opioid overdoses and opioid-related death rates. Overall, it was not associated with a change in all opioid ED encounters or deaths, despite a negligible increase in the rate of non-prescription opioid overdoses. These findings do not support assertions that this policy within the Affordable Care Act exacerbated the opioid epidemic. Future research is needed to understand the long-term effects of insurance expansion and the barriers to access of medications for opioid use disorder and treatment facilities, the role of private insurance in providing adequate access to treatment in this population, and whether this trend will continue as access to addiction treatment expands.

References

Johnson, S.R., Drugs for Dollars: How Medicaid Helps Fuel the Opioid Epidemic, C.o.H.S.a.G. Affairs, Editor. 2018.

Advisors, C.o.E, Innovative Policies to Improve All Americans’ Health. 2018.

Sommers, B.D. and R. Kronick, The affordable care act and insurance coverage for young adults. JAMA, 2012. 307(9): p. 913–914.

Sommers, B.D., et al., The Affordable Care Act has led to significant gains in health insurance and access to care for young adults. Health Aff, 2013. 32(1): p. 165–174.

Cantor Joel, C., et al., Early impact of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage of young adults. Health Serv Res, 2012. 47(5): p. 1773–1790.

Watkins, K.E., et al., The Affordable Care Act: an opportunity for improving care for substance use disorders? Psychiatr Serv, 2014. 66(3): p. 310–312.

Ali, M.M., et al., The ACA’s dependent coverage expansion and out-of-pocket spending by young adults with behavioral health conditions. Psychiatr Serv, 2016. 67(9): p. 977–982.

McClellan, C.B., The Affordable Care Act’s dependent care coverage expansion and behavioral health care. J Ment Health Policy Econ, 2017. 20(3): p. 111–130.

Saloner, B., et al., Access to health insurance and utilization of substance use disorder treatment: evidence from the Affordable Care Act dependent coverage provision. Health Economics, 2017: p. n/a-n/a.

Meinhofer, A. and A.E. Witman, The role of health insurance on treatment for opioid use disorders: evidence from the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion. J Health Econ, 2018. 60: p. 177–197.

Andrews, C.M., et al., Medicaid benefits for addiction treatment expanded after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff, 2018. 37(8): p. 1216–1222.

Venkataramani, A.S. and P. Chatterjee, Early Medicaid expansions and drug overdose mortality in the USA: a quasi-experimental analysis. J Gen Intern Med, 2018.

Sharp, A., et al., Impact of Medicaid expansion on access to opioid analgesic medications and medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Health, 2018. 108(5): p. 642–648.

Swartz, J.A. and S.J. Beltran, Prescription opioid availability and opioid overdose-related mortality rates in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states. Addiction, 2019. 0(0).

Dimick, J.B. and A.M. Ryan, Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. JAMA, 2014. 312(22): p. 2401–2402.

Heathcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS), A.f.H.R.a. Quality, Editor. 2009 and 2011–2013.

Prevention, C.f.D.C. Multiple Cause of Death 1999-2016. December 2017 December 2017 [cited 2018 May 18]; Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html.

Yokell, M.A., et al., Presentation of prescription and nonprescription opioid overdoses to us emergency departments. JAMA Intern Med, 2014. 174(12): p. 2034–2037.

Barbaresco, S., C.J. Courtemanche, and Y. Qi, Impacts of the Affordable Care Act dependent coverage provision on health-related outcomes of young adults. J Health Econ, 2015. 40: p. 54–68.

Burns, M.E. and B.L. Wolfe, The effects of the Affordable Care Act adult dependent coverage expansion on mental health. J Mental Health Policy Econ, 2016. 19(1): p. 3–20.

Akosa Antwi, Y., et al., Changes in emergency department use among young adults after the patient protection and Affordable Care Act’s dependent coverage provision. Ann Emerg Med, 2015. 65(6): p. 664–672.e2.

Walley, A.Y., et al., Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ, 2013. 346.

Bureau, U.S.C U.S. Population by Age and Sex. [cited 2018; Available from: https://www.census.gov/en.html.

Alpert, A., D. Powell, and R.L. Pacula, Supply-side drug policy in the presence of substitutes: evidence from the introduction of abuse-deterrent opioids. Am Econ J Econ Pol, 2018. 10(4): p. 1–35.

Hwang, C.S., H.-Y. Chang, and G.C. Alexander, Impact of abuse-deterrent OxyContin on prescription opioid utilization. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 2014. 24(2): p. 197–204.

Severtson, S.G., et al., Sustained reduction of diversion and abuse after introduction of an abuse deterrent formulation of extended release oxycodone. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2016. 168: p. 219–229.

Cicero, T.J. and M.S. Ellis, Abuse-deterrent formulations and the prescription opioid abuse epidemic in the united states: lessons learned from oxycontin. JAMA Psychiatry, 2015. 72(5): p. 424–430.

Coplan, P.M., et al., Changes in oxycodone and heroin exposures in the National Poison Data System after introduction of extended-release oxycodone with abuse-deterrent characteristics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 2013. 22(12): p. 1274–1282.

Cheng, H.G. and P.M. Coplan, Incidence of nonmedical use of OxyContin and other prescription opioid pain relievers before and after the introduction of OxyContin with abuse deterrent properties. Postgrad Med, 2018. 130(6): p. 568–574.

Horgan, C.M., et al., Behavioral health services in the changing landscape of private health plans. (1557–9700 (Electronic)).

Friedmann, P.D., C.M. Andrews, and K. Humphreys, How ACA repeal would worsen the opioid epidemic. N Engl J Med, 2017. 376(10): p. e16.

Reif, S., et al., Commercial health plan coverage of selected treatments for opioid use disorders from 2003 to 2014. J Psychoactive Drugs, 2017. 49(2): p. 102–110.

Hodgkin, D., et al., Federal parity and access to behavioral health care in private health plans. Psychiatr Serv, 2018. 69(4): p. 396–402.

Han, B., Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. adults: 2015 national survey on drug use and health. Ann Intern Med 167(5).

Finkelstein, A., et al., The Oregon health insurance experiment: evidence from the first year*. Q J Econ, 2012. 127(3): p. 1057–1106.

Taubman, S.L., et al., Medicaid increases emergency-department use: evidence from Oregon’s health insurance experiment. Science, 2014. 343(6168): p. 263.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

There are no contributors to the manuscript that did not meet authorship criteria.

Funding

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under award number T32HL098054 (EC), the National Institute on Drug Abuse K12DA033312 (EC), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development K23HD090272001 (MKD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Specific contributions are as follows: EC and MKD conceived the study and conducted the analysis. DK acquired the data. MKD, RMW, and DP provided statistical guidance and supervised the analysis. All authors interpreted the results. EC drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. EC takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coupet, E., Werner, R.M., Polsky, D. et al. Impact of the Young Adult Dependent Coverage Expansion on Opioid Overdoses and Deaths: a Quasi-Experimental Study. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 1783–1788 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05605-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05605-3