Abstract

Background

Women aged 50–70 should receive breast, cervical (until age 65), and colorectal cancer (CRC) screening; men aged 50–70 should receive CRC screening and should discuss prostate cancer screening (PSA). PreView, an interactive, individually tailored Video Doctor Plus Provider Alert Intervention, adresses all cancers for which average risk 50–70-year-old individuals are due for screening or screening discussion.

Methods

We conducted a randomized controlled trial in 6 clinical sites. Participants were randomized to PreView or a video about healthy lifestyle. Intervention group participants completed PreView before their appointment and their clinicians received a “Provider Alert.” Primary outcomes were receipt of mammography, Pap tests (with or without HPV testing), CRC screening (FIT in last year or colonoscopy in last 10 years), and PSA screening discussion. Additional outcomes included breast, cervical, and CRC screening discussion.

Results

A total of 508 individuals participated, 257 in the control group and 251 in the intervention group. Screening rates were relatively high at baseline. Compared with baseline screening rates, there was no significant increase in mammography or Pap smear screening, and a nonsignificant increase (18% vs 12%) in CRC screening. Intervention participants reported a higher rate of PSA discussion than did control participants (58% vs 36%: P < 0.01). Similar increases were seen in discussions about mammography, cervical cancer, and CRC screening.

Conclusion

In clinics with relatively high overall screening rates at baseline, PreView did not result in significant increases in breast, cervical, or CRC screening. PreView led to an increase in PSA screening discussion. Clinician-patient discussion of all cancer screenings significantly increased, suggesting that interventions like PreView may be most useful when discussion of the pros and cons of screening is recommended and/or with patients reluctant to undergo screening. Future research should investigate PreView’s impact on those who are hesitant or reluctant to undergo screening.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02264782

Similar content being viewed by others

BACKGROUND

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening mammography every 2 years for women aged 50 to 74, cervical cancer screening for women aged 50–64 every 3–5 years, and screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) for those aged 50–75.1 The American Cancer Society (ACS), the American College of Physicians (ACP), and others recommend a shared decision-making approach to prostate cancer screening (PSA).2 Although the USPSTF had recommended against PSA screening, their revised guidelines recommend a shared decision-making approach to PSA screening for men aged 55–69.3

Few cancer screening interventions address all screenings for which an individual is due. Women aged 50–70 should receive breast, cervical (until age 65), and CRC screening and men aged 50–70 should receive CRC screening and a PSA screening discussion.3,4,5,6

A successful cancer screening intervention must also (1) address individual stage of change,7,8,9 (2) be tailored to address individual barriers, and (3) support and simplify the clinician’s job.

The Transtheoretical Model posits that an individual passes through a series of stages when deciding whether or not to engage in a preventive behavior. The stages include precontemplation—never thought about screening, contemplation—thinking about screening, action—has completed at least one screening in appropriate time frame, maintenance—has completed at least two appropriate screening in appropriate time frame, or relapse—has been screened in the past and is not planning to be screened again.7,8,9

Barriers to receipt of screening can occur at the level of the clinician, the patient, or the system.10 Overcoming barriers can lead to completion of the preventive activity.

Since different individuals will be at different stages of readiness and will have different barriers to screening, messages about screening should be individually tailored both to an individual’s readiness and to his/her individual barriers to screening. In addition, an intervention should not create additional work but rather should “support and simplify” what the clinician is already doing.

We developed PreView, an Interactive Video Doctor intervention that simulates interaction with a real clinician. Patients are asked about readiness (based on the transtheoretical model) to undergo screening or screening discussion and individual barriers to screening. They receive individual tailored messages based on stage of change and individual barriers. The clinician receives a paper “Provider Alert” describing the patient’s readiness and individual barriers as well as possible responses that could facilitate overcoming the barriers.

We conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing the impact of PreView, an Interactive Video Doctor Plus Provider Alert Intervention, addressing all cancers for which an individual was due for screening or screening discussion, with usual care. Primary outcomes were primary care patients’ receipt of mammography, Pap tests, and CRC screening as well as discussions about PSA testing. Additional outcomes included discussions about breast, cervical and CRC screening.

METHODS

Intervention Sites

To ensure diversity, we intentionally chose a variety of primary care sites. All are part of the San Francisco Bay Area Collaborative Research Network, a primary health care practice-based research network supported by the UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Six clinics agreed to participate. One clinic withdrew after a short period: no participants from this clinic were included. The clinic that withdrew wanted to try a model where their staff members (rather than our research assistant) implemented the intervention; however, it was difficult to ensure intervention fidelity with this model and so we mutually agreed to withdraw this clinic. An additional clinic was recruited after this clinic’s withdrawal. The final sites included three federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), two large staff model private practices, and one small physician owned and operated clinic associated with a larger regional health organization.

Clinician Recruitment

The intervention was presented by clinic leaders as an intervention in which each primary care clinic would participate. Clinicians were told that they would potentially see patients in both intervention and control groups. .After the patient completed PreView on the iPad, a paper “Provider Alert” would be generated which the clinician could use if desired.

Although staff members were not formally recruited, we told staff and providers that we would solicit ongoing input about how to ensure the intervention ran as efficiently as possible at their sites.

Patient Recruitment

Eligible patients were age 50–70 with upcoming follow-up or preventive appointments. Patients whom clinicians deemed inappropriate (e.g., dementia, medical conditions precluding screening, or psychiatric illness) were not contacted. Participants were asked to come in early to ensure adequate time for consent and program completion before scheduled appointments.

Description of the PreView Plus Provider Alert Intervention

PreView (Preventive Video Education in Waiting Areas) is an interactive, multimedia “Video Doctor” plus Provider Alert intervention that simulates a discussion between clinician and patient. PreView is delivered on an iPad.

PreView starts with a welcome to the program and a series of health and risk assessment questions, asking about prior cancer screening (whether the person has ever been screened or up to date with screening) and readiness to change cancer screening behavior. Women are asked about breast, cervical, and CRC screening tests and men are asked about CRC screening tests and whether they have ever had a discussion about PSA screening with their provider. Stage of change is assessed according to the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (precontemplation, contemplation, action, maintenance, or relapse) with respect to cancer screening and perceived barriers to screening.9

The Video Doctor is then introduced and is designed to simulate a conversation between a patient and a real physician, including video and audio in order to provide a realistic experience. The program uses branching logic in order for individually relevant video clips to be shown according to the participant’s previous answers.

The participant receives an individualized message from the Video Doctor based on his/her stage of change for each cancer. For example, for breast cancer, individuals who are Precontemplators receive a message about the importance of mammography, whereas individuals in Maintenance receive a congratulatory message for taking care of their health. Participants all receive information about the norms and recommendations for screening for each cancer (based on USPSTF recommendations). Each individual is then asked about readiness to change. Individuals who are unsure or not ready receive individualized messages from the Video Doctor about the relevance, risks, and rewards of screening and then choose from an extensive list of barriers or roadblocks to screening.

Perceived barriers to screening are based on our prior research and the research of others11,12,13 and on published shared decision-making models for prostate cancer screening.14, 15 They are specific for each cancer and include options such as “I do not think I am at risk for breast cancer,” “I am concerned that a Pap test will be painful or uncomfortable,” “I don’t need to get tested [for CRC] because I don’t have any symptoms” (see Box 1 for a complete list of barriers). The participant can choose up to three roadblocks for each cancer. He/she then receives an individualized message from the Video Doctor tailored to each roadblock, including suggestions for overcoming that roadblock.

MAMM mammography, PAP Pap smear: cervical cancer screening module, CRC colorectal cancer screening module, PSA prostate cancer screening discussion module

After the intervention, a paper “Provider Alert” is generated, which can be used by the clinician. This alert outlines the participant’s stage of change, individual barriers to screening, and offers potential individual suggestions for overcoming the barriers.

We conducted a pilot study for feasibility and acceptability with 80 patients in 4 settings. The majority of men and women were interested in discussing and receiving a screening test when it was next due. Additionally, about 70% of all participants agreed or strongly agreed that the information provided helped them decide whether or not to be screened for breast, cervical, or CRC, or whether to have a PSA screening discussion with their providers.16

Procedure

After the participant consented, he/she was guided to the iPad located in the clinic waiting room and given headphones to maintain privacy. He/she was randomized to the intervention or the control group. All answered baseline questions. Participants in the control group received information about healthy diet and exercise while participants in the intervention group received the PreView plus Provider Alert intervention.

Post-visit Assessment

After the visit, participants returned to the iPad to answer a series of questions, which assessed intention to change screening behavior, and whether each cancer screening test was ordered or discussed during the visit. Men were asked if they discussed PSA screening during the visit. Intentions were measured on a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from very unlikely to very likely.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were being “up to date” with breast, cervical, and CRC screening 14 months after the intervention date. Although the earliest interval during which a participant might be due would be 12 months, if he/she was given a fecal immuochemical test at 12 months, he/she would need time to complete it so we chose a 14-month follow-up. Methods for determining whether a participant was up to date with breast, cervical, and CRC screening are described in Box 2. For PSA screening, the outcome was a discussion about the pros and cons on the date of the study intervention as reported by the patient. Receipt of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) alone did not qualify as a discussion. Secondary outcomes included readiness to discuss or engage in screening or screening discussion for all cancers.

Outcomes were measured by chart review. All reviewers were blinded to group assignment. If a screening test or discussion was not documented in the chart, the participant was contacted by phone. Participants were asked about screenings they had over the past several years (depending on which test). For example, some participants reported colonoscopies that had taken place 6 years earlier that were not in the records of the primary care clinician.

If the participants said that he/she had not had the tests or discussion, this was documented. If he/she indicated that she had the test or discussion, then the participant was asked where he/she had the test. With the participant’s permission, medical records were requested from the outside institution.

Since we intentionally conducted the intervention in 6 diverse sites, all with different record keeping systems, the approach to record review was slightly different in each setting. Some settings had paper charts and then transitioned to an electronic health record (EHR) over the course of the study, while others changed EHR systems over the course of the study. We reviewed electronic and when appropriate, paper records, to ensure full data collection.

Our primary outcome was being up to date with the screening test as documented by any measure (including self-report). We also performed a secondary analysis using only outcomes that were validated by chart review. Additional secondary outcomes included readiness to be screened or to discuss screening as measured by participant responses during the post-visit assessment.

Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4.17 Descriptive statistics were computed for all measures, including means, standard deviations, and percentages, separately for control and intervention subgroups. Items measuring how likely the patient would discuss were dichotomized into “likely” vs. “not likely,” those measuring beliefs and attitudes were collapsed into “agree” and “disagree,” and those measuring intention, into “likely” and “unlikely.” For those measures defined as “yes,” “no,” or “don’t know,” don’t know responses were included in the “no or don’t know” category for analyses.

We analyzed baseline data to explore differences in demographic factors and and in the outcomes between control and intervention groups.

We also used linear models with a normal link function to determine any difference between the two groups of the change in proportion from pre to post-intervention. To further evaluate changes from baseline to post-intervention, we used generalized linear models with a logit link function on binary outcomes while adjusting for baseline values and for age of the participants as a potential covariate. We adjusted for gender differences.

We report descriptive statistics and P values for the group differences for each of the outcomes. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

There were no significant baseline differences between the intervention and control groups (Tables 1 and 2). The average age of participants was 59 and, as is typical in primary care clinic settings, there were more women than men (60% compared with 40%). Over one-third of participants were African-American and approximately 10% were Asian. Just less than half (46%) had a high school education or less. The majority had health insurance; approximately half of participants had private health insurance and approximately 40% had MediCare. Slightly less than a third of participants rated their health as fair or poor.

Primary Outcomes

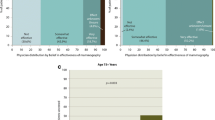

We compared screening rates at baseline and follow-up. For mammography, the baseline rate of being up to date in the intervention group was 80.8% compared with the 72.4% in the control group (P = NS). The rate in the control group increased by 6% versus 4% in the intervention group, a difference that was not statistically significant. Similarly, for cervical cancer, the baseline rate was higher in the control group than in the intervention group (73.8% vs 67.6%: P = NS). The rate in the control group increased by 13.9% whereas that in the intervention group increased by 10.7%, a difference that was not statistically significant. For CRC screening, the baseline rate was nonstatistically higher in the control group (65% vs 61%). CRC screening rates increased by 17.9% in the intervention group and 11.7% in the control group; this difference was not statistically significant.

We do not have baseline rates of prostate cancer screening discussion, because discussion is not routinely documented in a systematic way. Participants were asked during the post-visit assessment “When you met with your doctor today, did you discuss the pros and cons of PSA testing?” Significantly more intervention participants than control participants reported PSA discussion (58% vs 36%: P < 0.01).

Cancer Screening Discussions

In Table 3, we describe participant responses to questions asked during the post-visit assessment. Intervention group participants were significantly more likely to discuss having a mammogram, to discuss when next to get a mammogram, and to indicate more readiness to be screened. Similarly, intervention group participants described more discussion about having a Pap test and when next to have a Pap test and CRC screening and when next to have CRC screening. More intervention group participants indicated that they discussed PSA screening and that they would be likely to ask their doctor about the pros and cons of PSA screening at their next visit.

Staff and Provider Input

We collected ongoing feedback from staff members and providers to ensure that PreView could be implemented efficiently in their settings. Staff members did not feel that it interfered with clinical flow and providers did not feel that it added any additional work.

DISCUSSION

Primary care clinicians address multiple medical issues and also try to ensure that all health care maintenance items are addressed for a particular patient. PreView is unique in that it targets all cancers for which an individual participant is due (Table 4). In addition, the messages are individually tailored both to stage of change and to individual barriers to screening or discussion.

Screening rates were relatively high at baseline in these participating clinics, making it harder to see increases in screening. The increase in screening rates was higher among clinics with lower baseline rates (Supplemmentary Tables 5 and 6), suggesting that the ceiling effect had an important contribution.

Discussion of mammography, cervical cancer screening, and CRC screening increased in all intervention group participants. This may be less relevant in those who are planning to obtain screening anyway, but could potentially have a larger impact in individuals who are not sure at about whether or not to be screened. Given logistic issues in the various clinical settings, we were unable to select participants based on whether or not they were due for screening, but this may be a useful future tactic for identifying who is most likely to benefit from PreView.

For prostate cancer, the main outcome was discussion of the pros and cons of screening, as discussion of the pros and cons of screening is currently recommended by multiple organizations.2 Measuring discussion is more difficult than measuring whether a screening test is ordered. Our primary prostate cancer screening outcome was “Discussion of the pros and cons of PSA testing” as reported by the participant after the visit. Intervention group participants were significantly more likely to report discussion of PSA testing and were more likely to indicate intent to discuss PSA testing at the next visit.

Our study had several limitations. High baseline screening rates made it harder to see increases in screening rates. We were unable to select only those patients with upcoming appointments who were due for a screening, thus potentially including individuals who were already up to date with screening. Finally, since “discussion” of the pros and cons of PSA testing is inconsistently documented in clinical charts, we were unable to measure baseline rates of PSA discussion or to validate participants self-report by review of the medical records. However, the large difference between intervention and control seems unlikely to have occurred by chance.

PreView was most useful for those interventions where discussion was the outcome, such as decision-making about prostate cancer screening and could potentially be quite useful in encouraging discussion in those who are reluctant to be screened for other cancers. Interventions like PreView may also be useful in situations where discussion and shared decision-making are encouraged, such as mammography screening for women in their forties and those aged 75 and older.5

PreView, the interactive Video Doctor plus Provider Alert intervention, led to more discussion about screening and more readiness to be screened. It may also be useful in advancing individuals along the stages of change toward readiness to be screened or to discuss screening.18, 19 There are many areas of primary care where there is not a single course of action, where shared decision-making is encouraged, and interventions like PreView which focus on stage of change and perceived barriers to screening or discussion can have a real impact.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF): An Introduction. [cited 2018; Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/uspstf/index.html.

Wolf AM, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 60(2): p. 70-98.

Moyer VA, U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med, 2012. 157(2): p. 120-34.

Moyer VA, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med, 2012. 156(12): p. 880-891.

Siu AL, U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med, 2016. 164(4): p. 279-96.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med, 2008. 149(9): p. 627-637.

Kumar AT, Gadiyar A, Gaunkar R, Kamat AK. Assessment of readiness to quit tobacco among patients with oral potentially malignant disorders using transtheoretical model. J Educ Health Promot, 2018. prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive.

Levesque D, Umanzor C, de Aguiar E. Stage-Based Mobile Intervention for Substance Use Disorders in Primary Care: Development and Test of Acceptability. JMIR Med Inform, 2018. 6(1): p. e1.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change. Am J Health Promot, 1997. 12(1): p. 38-48.

Walsh J, McPhee S. A Systems Model of Clinical Preventive Care: An Analysis of Factors Influencing Patient and Physician. Health Educ Q, 1992. 19(2): p. 157-175.

Hiatt RA, et al. Community-Based Cancer Screening for Underserved Women: Design and Baseline Findings from the Breast and Cervical Cancer Intervention Study. Prev Med 2001. 33(3): p. 190-203.

Walsh JME, et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Latino and Vietnamese Americans. J Gen Intern Med, 2004. 19(2): p 156-166.

Walsh JME, et al. Healthy colon, healthy life: a novel colorectal cancer screening intervention. Am J Prev Med 2010. 39(1): 1-14.

Chan ECY, Sulmasy DP. What should men know about prostate-specific antigen screening before giving informed consent? Am J Med 1998. 105(4): p. 266-274.

Sheridan SL, et al. Information needs of men regarding prostate cancer screening and the effect of a brief decision aid. Patient Educ Couns 2004. 54(3): p. 345-351.

Arora M, et al. PRE-VIEW: Development and Pilot Testing of An Interactive Video Doctor Plus Provider Alert to Increase Cancer Screening. ISRN Prev Med, 2013. 2013.

SAS Institute. 2017. Cary, NC

Kumar A, et al. Assessment of readiness to quit tobacco among patients with oral potentially malignant disorders using transtheoretical model. J Educ Health Promot, 2018. 7: p. 9.

Levesque D, Umanzor C, de Aguiar E. Stage-Based Mobile Intervention for Substance Use Disorders in Primary Care: Development and Test of Acceptability. JMIR Med Inform, 2018. 6(1): p. e1.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the clinicians, staff, and patients at our six UCSF Clinical Research Network Sites (John Muir Medical Center – Concord, San Ramon Valley Primary Care (now known as John Muir Health), Family Care Associates, Lifelong Medical Care – West Berkeley, Highland Hospital Adult Medicine Clinic, and Southeast Medical Center) for their enthusiastic participation in the PreView randomized trial.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (NIH-R01-CA-158027) and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02264782).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 20.2 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walsh, J., Potter, M., Salazar, R. et al. PreView: a Randomized Trial of a Multi-site Intervention in Diverse Primary Care to Increase Rates of Age-Appropriate Cancer Screening. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 449–456 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05438-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05438-0