Abstract

Background

Although research shows produce prescription (PRx) programs increase fruit and vegetable (FV) consumption, little is known about how participants experience them.

Objective

To better understand how participants experience a PRx program for hypertensive adults at 3 safety net clinics partnered with 20 farmers’ markets (FMs) in Cleveland, OH.

Design

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 5 program providers, 23 patient participants, and 2 FM managers.

Participants

Patients interviewed were mainly middle-aged (mean age 62 years), African American (100%), and women (78%). Providers were mainly middle-aged men and women of diverse races/ethnicities.

Intervention

Healthcare providers enrolled adult patients who were food insecure and diagnosed with hypertension. Participating patients attended monthly clinic visits for 3 months. Each visit included a blood pressure (BP) check, dietary counseling for BP control, a produce prescription, and produce vouchers redeemable at local FMs.

Approach

Patient interviews focused on (1) beliefs about food, healthy eating, and FMs; (2) clinic-based program experiences; and (3) FM experiences. Provider and market manager interviews focused on program provision. All interviews were audio-taped, transcribed, and analyzed thematically.

Key Results

We identified four central themes. First, providers and patients reported positive interactions during program activities, but providers struggled to integrate the program into their workflow. Second, patients reported greater FV intake and FM shopping during the program. Third, social interactions enhanced program experience. Fourth, economic hardships influenced patient shopping and eating patterns, yet these hardships were minimized in some participants’ views of patient deservingness for program inclusion.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight promises and challenges of PRx programs for economically disadvantaged patients with a chronic condition. Patient participants reported improved interactions with providers, increased FV consumption, and incorporation of healthy eating into their social networks due to the program. Future efforts should focus on efficiently integrating PRx into clinic workflows, leveraging patient social networks, and including economic supports for maintenance of behavior change.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Produce prescription (PRx) programs leverage the symbolic power of a physician’s prescription to link patients to farmers’ markets (FMs), improving access to fresh produce. Studies indicate PRx programs increase fruit and vegetable (FV) consumption1,2,3 and have potential to help patients manage chronic conditions such as hypertension, a major risk factor for heart disease and stroke and a focus of Healthy People 2020.4

Growing literature examines contextual factors shaping PRx interventions. Sorensen et al.,2 for example, found social contexts and economic constraints matter. The authors found supportive social norms were correlated with greater change in FV consumption, but financial strain limited improvements. Despite growing research on PRx programs,1, 3, 5,6,7,8,9 few studies focus on how participants experience them. Such information has potential to help improve program implementation and impact.

Because PRx interventions are often promoted to address low FV consumption among under-resourced groups disproportionately affected by chronic disease, there is particular need to better understand how these individuals experience them.10 This study draws on a qualitative process evaluation of a PRx program for hypertension (PRxHTN) including largely older African American adults diagnosed with hypertension, experiencing food insecurity, and engaged in care at safety net primary care clinics in Cleveland, OH. Our goal is to inform the literature on how PRx programs translate to everyday lives of people who struggle with chronic disease and limited economic resources.

METHODS

Intervention

PRxHTN was developed by members of Health Improvement Partnership-Cuyahoga consortium (http://hipcuyahoga.org): a collaboration between 3 safety net clinics (i.e., 30% or more of their patient population received Medicaid or were uninsured) and 20 FMs in Cuyahoga County, OH. The program sought to increase access to and consumption of FV among participating patients. Detailed implementation information is available elsewhere.8 In brief, trained healthcare providers (pharmacists, medical assistants, nurse care coordinators) enrolled adult patients (aged 18 or older) who screened positive for food insecurity based on a 2-item validated questionnaire11 and were diagnosed with hypertension (for any duration). Participating patients attended monthly visits with the provider for 3 months during the FM season (July–December 2015). Each visit included a blood pressure (BP) check, tailored dietary counseling to improve BP control, a produce prescription, and produce vouchers ($40 per month) redeemable at participating local FMs.

Approach

We used a qualitative process evaluation approach process evaluation approach using semi-structured open-ended interviews with patients, providers, and market managers. Our approach focused on the pragmatic objective to understand how effective PRxHTN was with respect to its intended goals and participant needs and the interpretive objective to understand how participants (patients, providers, market managers) understood and enacted the program in everyday contexts of its implementation.12

Sample and Recruitment

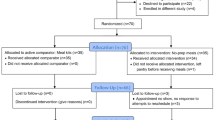

We interviewed 23 patients (6–8 per clinic) recruited via mail-in response card sent to all PRxHTN participants who consented to follow-up contact (210 of 224). A total of 80 patients returned response cards, of which we selected interviewees to achieve variation in clinic, age, gender, and economic position. Patients who we interviewed were largely middle-aged (mean age, 62 years), African American (100%), and women (78%), mirroring the sociodemographic characteristics of program participants overall, with the exception of education level (interviewees had higher levels of education than the overall sample) (see Table 1).

We interviewed five of seven healthcare providers who implemented and delivered the PRxHTN program (at least 1 provider per clinic, including a pharmacist, medical assistants, and patient care coordinators). Providers were recruited based on their prominent role in implementing PRxHTN at their respective clinics. We interviewed two managers who coordinated PRxHTN at local FMs. We selected managers who coordinated the program at FMs that recorded the highest voucher redemption, and thus where the majority of participants redeemed vouchers. Providers and managers were invited to participate by email invitation. Participating providers and market managers were middle-aged men and women of diverse race/ethnicities.

Patients were compensated for interviews with $15 worth of FM vouchers. Providers and market managers were compensated with $25 FM vouchers and $25 Visa gift cards respectively. All study procedures were approved by the MetroHealth Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Interviews

All interviews were conducted in person, in community settings (e.g., health centers, libraries, patient homes), following semi-structured guides. Patient interviews included questions regarding their beliefs about food, healthy eating, and FMs; experiences of PRxHTN at clinics; and experiences of PRxHTN at FMs. Following an iterative research approach, we added additional questions about patients’ food histories, eating patterns, and grocery shopping routines after preliminary data analysis. Program provider and market manager interviews focused on their observations of the PRxHTN population regarding eating patterns, FV access, health beliefs, and economic resources; their experiences implementing the program; and suggestions for program improvement. Interviews lasted approximately 45 min and were conducted from March to August 2016 (3–8 months post-intervention).

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using NVIVO qualitative data analysis software. We conducted thematic analyses of a priori themes related to program goals and processes and emergent themes regarding participant experiences.13 Two investigators independently coded 10% of the interviews, achieving 80% inter-coder reliability.

We compared patient, provider, and market manager perspectives, and used provider and manager data to contextualize patient program experiences. While we achieved thematic saturation in patient data, we did not reach thematic saturation in provider and manager data due to the small number of targeted individuals sampled from these groups.

FINDINGS

We identified four central themes: (1) clinic experiences, (2) education and behavior change, (3) social dynamics, and (4) economic hardship (see Table 2).

Theme 1: Clinic Experiences

Provider and patient program experiences at clinics centered on the program’s role in communicating provider care for patients and workload challenges providers faced in implementing the program.

Communicating “Care”

PRxHTN provided structure and time for providers and patients to discuss eating patterns and nutrition goal-setting. Diane,Footnote 1 a nurse care coordinator, noted, “[PRxHTN] really energized me. It was a lot of fun for me, personally, because I got to do this great education about hypertension.” Both providers and patients reported that clinic time for conversations about food and healthy eating communicated that providers “care” for patients. Robert, a pharmacist, observed: “A lot of people here think that we don’t care about them…They feel that they are underprivileged, so people don’t really care. When we do things like this, it shows a lot of effort on our part to help them, and that touches them.” Patients echoed this sentiment, commenting that PRxHTN made them realize, “there is someone out there that does care that you do better with healthier eating” (Lisa, African American woman, age 33).

Workload Challenges

Despite these positive interactions, providers experienced workload challenges completing PRxHTN activities. Diane, the nurse care coordinator who was “energized” by providing hypertension education, explained, “It was hard doing [PRxHTN] on a one-to-one basis…if I had an issue with [a patient] while [they] were here and I had to take care of it, I didn’t have time to go through the [PRxHTN] scenario.” Patients also reported limited time to ask questions during PRxHTN education.

One clinic delivered PRxHTN education in a group format to manage workload challenges, creating a positive social space for patients. Brenda (African American woman, age 64) appreciated peer interaction during group sessions: “We just enjoyed ourselves, enjoyed the people participating in the class also.” Glenda (African American woman, age 55) benefited from a sense of belonging fostered during group sessions: “I was able to find out from other people where things I thought it was just me, it wasn’t just me. So it was helpful to kind of let loose and talk to other people that had the same health condition that I have and find out what they do to help them with their high BP.”

Theme 2: Education and Behavior Change

Patients reported greater knowledge of produce and increased FV intake during the program. They also reported greater knowledge of FMs as a result of PRxHTN participation.

Healthy Eating Education and Produce Intake

Patients reported learning about novel FVs and food preparation and storage methods through PRxHTN. Arlene (African American woman, age 78) stressed that the financial support of PRxHTN enabled experimentation with new FV: “I usually see Swiss chard, but I don’t bother with it. There were some other vegetables that I tried because when you see them in the store, you know they’re expensive and so you just get the ones that you usually get.” Patients also altered their eating patterns due to PRxHTN education and voucher support. Louise (African American woman, age 62), for example, described healthier snacking: “Every time I’d go in the kitchen, I would see the fruit on the table and it’d just—okay, get a piece of fruit.”

Farmers’ Market Knowledge

Most patients learned about FMs for the first time through PRxHTN. Patients learned about FM locations, their focus on local and seasonal produce, and menu planning and food preparation conducive to FM shopping. When asked what he learned from the program, Larry (African American man, age 63), responded, “I didn’t know that [FMs] are affiliated, and the fact that the food is grown locally. So I learned everything about the FMs. I was surprised.” Despite gaining knowledge of FMs, some patients reported the need for more specific orientation to market practices and navigation with which they were largely unfamiliar.

Theme 3: Social Dynamics

Patients experienced PRxHTN through social relationships; they often included family members in program participation and experienced FMs as positive social spaces.

Family Influence and Involvement

Patients often viewed PRxHTN as a family-level intervention. As Jennifer (medical assistant) observed, “a lot of people are like, ‘Well I want my family to eat healthier too. That’s why I want to do this.’” Participants drew on family histories growing FV, often during childhoods in agricultural communities in the Southern United States, to understand healthy food and eating. Brenda, whose appreciation of group education we describe above, recalled, “[My father] always had a garden in our backyard. Grew greens, cabbage, tomatoes and other stuff and worked on a farm.” Others, like James (African American man, age 64), noted familiarity with produce due to family histories growing FV: “Everything that’s on here [program handout], we ate this when we were younger. We had our own strawberry patch and we grew our own foods.”

Some patients participated in PRxHTN with family members also formally enrolled (e.g., spouses, parents, children). Non-enrolled family members also benefited, as participants exposed their households to nutrition education and produce. Patricia (African American woman, age 60) communicated program information to family members and cooked FV for them: “I share with [family] the things that I learn…so that they know, and they pretty much go along with the things that I tell them. So we’re all getting healthier…I usually cook for my mom and myself and we’ve started to eat a lot of FV because of what the program has taught us.”

These benefits spread through familial networks beyond households. Patients’ adult children and grandchildren benefited from increased access to FV, new food preparation techniques, and program materials. Brenda explained, “I even called up some of my family members [and said], ‘Did you know this?’ or ‘You shouldn’t do that’… So that way I could take it forth and present it to my family.”

Family frequently accompanied patients to markets because participants relied on them for transportation, providing additional opportunities to spread PRxHTN benefits through families. Some participants explicitly viewed market visits as occasions to educate family on healthy eating. Lisa, who felt PRxHTN communicated provider care for her health, brought her son to markets, “to educate him on the FM and he really enjoyed it. So I educated him, just like I was educated.” Some participants drew on the knowledge of older family members at markets. Rose (African American woman, age 55) attended FMs with her mother, who “came with me most of the time. I said, ‘This is a unique experience for us, for you to teach me how to pick out vegetables.’”

Social Space of Farmers’ Markets

FMs provided space for positive social interaction, particularly significant for elderly participants with limited social outlets. Laura, a medical assistant, observed: “It’s not like they just go to their appointment and go back home, because they don’t have nowhere else to go, or just go to their regular grocery store. They can actually do something that is outside and they can enjoy it, and you can see a difference when they come back.” The most engaged participants, like Sandra (African American woman, age 61), developed ongoing relationships with market vendors: “I got to know people, and I had one vendor that I really like and we developed a nice relationship, and I was looking forward to seeing him [to ask], ‘What we got this Saturday?’”

Theme 4: Economic Hardship

Patients’ lives were marked by economic insecurity, shaping program participation and limiting their ability to maintain behavior change. Economic challenges were at times minimized by patients and market managers who emphasized individual motivation for behavior change.

Economic Insecurity

Food insecurity was part of the eligibility criteria for program enrollment, and this context was reflected in interviews. Patients stressed that PRxHTN vouchers offered some relief. Patients described significant economic insecurity and reliance on food assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and food pantries to meet their basic nutritional needs. While some participants reported the ability to obtain produce at local food pantries, they noted that reliance on these organizations limited their ability to choose healthy foods. Dependence on food assistance shaped shopping patterns, influencing participants to buy in bulk or purchase only sale items. Tina (African American woman, age 61) shared that, “Some people go shopping and go buy up a whole bunch of stuff, and it lasts a whole month. I only get 15 bucks [in SNAP per month], so I basically set my shopping schedule around what’s on sale.”

Older adults frequently survived on fixed incomes that limited grocery shopping. Joyce (medical assistant) noted, “if [patients] live on Social Security, they only had that certain amount left the whole month. So by the end of the month, they wouldn’t have enough money to go and buy food. They just gotta get whatever they have left.” Multi-morbidities, which were common, exacerbated financial hardship. Patients receiving disability benefits, like Beverly (African American woman, age 69), reported difficulty affording both food and medicine: “I had the money to go grocery shopping, but I have to sparingly spend it, ‘cause the next month I might need more money for medicine.”

PRxHTN vouchers gave these patients the economic support necessary to increase FV intake. For Sandra, PRx education “highlighted that we need to eat healthier…with the coupons [produce vouchers], that option just made it possible.” Nearly all patients, however, limited their FV shopping to what could be purchased with PRxHTN vouchers due to lack of personal funds: “The fact of the matter is,” explained Larry, “the coins [from PRxHTN vouchers] could only buy so much, so [I] wasn’t really trying to stay in the Pyramid [following program education]. It was just trying to get what the coins could buy.”

Lack of reliable transportation and money for gas further shaped program experience. Tina shopped at FMs, “in a close area, based on my income. I try to make my gas last as long as possible. I fill up and hopefully it’ll last me a month.” She explained that individuals alter shopping based on limited transportation: “You want to space [FM shopping] out because the food will go bad. If you don’t have a ride, then you’ll change what you’re gonna buy.”

Limited Maintenance of Behavior Change

Many patients viewed the produce quality and variety available at FMs as a luxury afforded only by the time-limited program. When asked why she chose to enroll in the program, Lisa responded, “You were offering [produce] tokens and it didn’t cost me anything, so it was like getting healthier food for little or nothing. No more than some time, and I’m willing to dedicate time for that type of food.” Despite increased FV consumption and FM shopping during the program, most patients were unable to maintain these changes after the program ended due to economic hardships.

Motivation and Deservingness

Some patients and market managers minimized patient economic hardships and emphasized individual motivation for behavior change. Several patients, and both market managers, stressed the importance of “serious” program engagement. Patricia, a patient, noted, “You always have some people that are just there for the freebies, but there’s people in there that are really serious.” Heather, a market manager, articulated a similar view: “There’s something that is giving individuals that get stuff for free the mindset of not being responsible for their own selves.” She later emphasized patient accountability to avoid the mindset that, “I’m getting these vegetables. I’m just gonna give them away, sell them, eat some of them, let the rest of them rot.” These comments are consistent with views of the other manager interviewed.

These views imply a perception that patients who utilize the program for food access without additional health-related motivations are acting irresponsibly and are less deserving of program participation than others.

DISCUSSION

Our findings highlight the promises and challenges of a PRx program for patients with complex health and economic needs. Patients and providers reported positive clinic interactions despite challenges integrating the program into clinic workflow. Patients reported greater knowledge of and access to produce and FMs during program participation. Social interactions enhanced patient program experiences and broadened its reach by diffusing benefits through familial networks. Yet economic hardships influenced patient shopping and eating patterns in ways that limited their ability to maintain health behavior changes. These hardships were minimized in some patient and market manager views of deserving program participation.

These findings echo previous research on produce prescription programs that link patients to FMs by demonstrating increases in health behaviors such as fruit and vegetable consumption,3 and improvements in health outcomes such as decreases in patient body mass index6 and hemoglobin A1c levels.5 Furthermore, our findings are consistent with research demonstrating positive experiences among clinic providers and patients as a result of produce prescriptions provided during clinic encounters that enable patients to afford fresh fruits and vegetables by shopping at FMs, thereby helping them to overcome household food insecurity.1, 9 Our findings echo research showing increased patient awareness and use of FMs due to program participation,3, 9 and the importance of social support in program effectiveness,2 including the ways FMs may provide positive social space.10 Finally, our findings join research underscoring the need for additional supports to bolster sustainable behavior change.9

By applying qualitative methods to better understand the converging and diverging perspectives of intervention collaborators (providers, patients, and market managers), this study adds depth and nuance to the existing literature. Further, we identified novel themes regarding beliefs about patient motivation for behavior change that imply judgments regarding deserving program participation. These findings have yet to be explored in-depth in the literature on PRx programs, but are consistent with literature on health-related deservingness in other contexts such as health care for immigrants.14

Our findings have implications for future interventions and clinical practice. Findings regarding PRxHTN as a mechanism for providers to communicate care for patients, and for patients to feel cared for, suggest there are few existing opportunities for providers to signal their concern for patients as whole persons. Time devoted to program activities such as goal-setting and discussions of eating patterns and food preparation not only fostered this sense of care but also enhanced program engagement among patients. Yet providers and patients felt “rushed” through these activities. These findings are consistent with research identifying limited time as a common barrier to nutrition counseling in primary care.15,16,17,18,19

Dedicating greater time to discussion of healthy eating during clinical encounters has potential to improve provider-patient interactions in the context of programs like PRxHTN and primary care generally. Such improved interactions may foster more therapeutic provider-patient relationships built on shared understandings of the nature of the problem, intervention goals, and psychosocial needs,9 and reduce provider burnout. In this context, we use the term provider broadly to include pharmacists, medical assistants, nutritionists, and other primary care team members that are increasingly being drawn into team-based primary care models. To leverage these potential benefits within limited time available in primary care visits, these providers could integrate brief, ongoing discussions of healthy food and eating at the end of a patient visit, providing resources and emphasizing small goals reinforced at subsequent visits, as Kahan and Manson16 suggest.

Social interaction between patients at clinics in group education appeared to enhance patient program engagement by providing them with a sense of social belonging and opportunities for peer information exchange. Future interventions could benefit from integrating similar groups that dedicate time and space for peer support.9 These groups have potential to decrease the burden of program implementation placed on clinic staff. More generally, such groups could help shift responsibility for nutritional counseling from primary care physicians to “physician extenders,”16 including peers.

Additionally, findings regarding the ways patients integrated family members into program activities underscore the potential of leveraging social networks to diffuse program education and resources. Intentionally integrating family members, friends, and peers into program activities and clinical interactions could foster greater incorporation of program education into the everyday lives of participants,10 supporting their ability to maintain health behavior change. For example, providers might include family members and peer health coaches in discussions of healthy eating and incorporate them in nutrition goal-setting.

Finally, findings on patient economic hardships highlight the structural barriers faced by individuals most affected by hypertension—older African Americans living in poverty20—in their efforts to engage in programs like PRxHTN. Some patients and market managers, however, discussed health behavior change in ways that emphasized individual motivation. Healthcare increasingly emphasizes patient “co-responsibility”21 through concepts such as “patient activation” that stress patient knowledge, confidence, and skills to care for their health and engage in healthcare.22 Expectations for patient co-responsibility and activation must be understood in the contexts of their lives that may be shaped by poverty.

Elsewhere we have suggested enhancing the “structural competency”23, 24 of programs like PRxHTN by using a structural vulnerability checklist25 to assess factors influencing healthy eating above the individual level (e.g., access to transportation, financial security, discrimination).26 Integrating a structural vulnerability checklist or social determinants of health screener at clinic and community intervention sites has potential to support primary care providers in better understanding and responding to the needs of socioeconomically vulnerable patients.

Our findings should be considered in the context of study limitations. First, because patient recruitment relied on their initiative to return response cards, interview responses are likely to reflect perspectives of participants with greater investment in the program and more stable living situations. These individuals provide a strong understanding of what worked well in program implementation, but potentially provide limited information about patients who are less engaged and more transient. Second, our sample of providers was small since we only delivered the program at 3 safety net clinics. While these interviews helped contextualize patient data, they do not represent the views of all providers who might implement this program. We sampled a small number of market managers based on their significant involvement in PRxHTN implementation. These interviews provided valuable information to contextualize patient data, but are not representative of the views of all managers who implemented the program.

Despite these limitations, our findings highlight the benefits of a PRx program for patients with chronic disease, including and beyond improvements in healthy eating, and point to ways these benefits might be leveraged in future efforts to improve clinical interactions between patients and providers, promote greater engagement of patients, and better meet patient economic needs. These findings and their implications are consistent with calls for patient-centered care that considers patients holistically, attending to their economic, emotional, and social needs to improve patient experience, increase intervention effectiveness, and reduce health disparities.27

Notes

All names are pseudonyms.

Abbreviations

- PRx:

-

Produce prescription

- FMs:

-

Farmers’ markets

- FV:

-

Fruit and vegetable

- PRxHTN:

-

Produce prescription program for hypertension

References

Goddu AP, Robertson TS, Raffel KE, Chin MH, Peek ME. Food Rx: A community-university partnership to prescribe healthy eating on the south side of Chicago. J Prev Interv Commun. 2015;43(2):148–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2014.973251

Sorensen G, Stoddard AM, Dubowitz T, et al. The influence of social context on changes in fruit and vegetable consumption: Results of the Healthy Directions studies. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1216–1229. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.088120

Trapl ES, Smith S, Joshi K, Osborne A, Benko M, Matos AT, et al. Dietary Impact of Produce Prescriptions for Patients With Hypertension. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:180301. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.180301

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Heart disease and stroke. In: Healthy People 2020. 2016. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/heart-disease-and-stroke. Accessed 1 June 2017

Bryce R, Guajardo C, Ilarraza D, et al. Participation in a farmers’ market fruit and vegetable prescription program at a federally qualified health center improves hemoglobin A1C in low income uncontrolled diabetics. Prev Med Rep. 2017;7:176–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.06.006

Cavanagh M, Jurkowski J, Bozlak C, Hastings J, Klein A. Veggie Rx: an outcome evaluation of a healthy food incentive programme. Public Health Nutr. 2016;20(14):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980016002081

Freedman DA, Peña-Purcell N, Friedman DB, et al. Extending cancer prevention to improve fruit and vegetable consumption. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29(4):790–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-014-0656-4

Joshi K, Smith S, Bolen SD, Osborne A, Benko M, Trapl ES. Implementing a produce prescription program for hypertensive patients in safety net clinics. Health Promot Pract. 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839917754090

Trapl ES, Joshi K, Taggart M, Patrick A, Meschkat E, Freedman DA. Mixed methods evaluation of a produce prescription program for pregnant women. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2017;12(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2016.1227749

Freedman DA, Vaudrin N, Schneider C, et al. Systematic review of factors influencing farmers’ market use overall and among low-income populations. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(7):1136–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2016.02.010

Hager, E. R., Quigg, A. M., Black, M. M., Coleman, S. M., Heeren, T., Rose-Jacobs, R., ... & Cutts, D. B. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):e26–e32. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3146

Greene J. Qualitative program evaluation: Practice and promise. In: Denzin NK and Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994:530–544.

Bernard RH, Ryan GW. Text analysis. In: Bernard RH, ed. Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press; 1998:595–646.

Willen S. How is health-related “deservingness” reckoned? Perspectives from unauthorized im/migrants in Tel Aviv. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(6):812–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.033

Eaton CB, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Direct observation of nutrition counseling in community family practice. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(3):174–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00494-4

Kahan S, Manson JE. Nutrition counseling in clinical practice: How clinicians can do better. JAMA. 2017;e1–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.10434

Kolasa KM, Ricket K. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25(5):502–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533610380057

Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutritional counseling by physicians: A survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med. 1995;24:546–50. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1995.1087

Wynn K, Trudeau JD, Taunton K, et al. Nutrition in primary care: Current practices, attitudes, and barriers. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:e109–16.

Gillespe CD, Hurvitz KA. Prevalence of hypertension and controlled hypertension – United States, 2007 - 2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(03):144–148.

Scott MA, Wright R. Increasing access, increasing responsibility: Activating the newly insured. In: Mulligan JM and Castaneda H, eds. Unequal coverage: The experience of health care reform in the United States. New York: New York University Press; 2018:254–275.

Greene J, Hibbard JH, Alvarez C, et al. Supporting patient behavior change: Approaches used by primary care physicians whose patients have an increase in activation levels. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):148–154. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1904

Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032

Hansen H, Metzl JM. New Medicine for the U.S. Health Care System. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):279–281. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001542

Bourgois P, Holmes SM, Sue K, et al. Structural vulnerability: Operationalizing the concept to address health disparities in clinical care. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):299–307. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001294

Schlosser AV, Joshi K, Smith S, et al. “The coupons and stuff just made it possible”: Economic constraints and patient experiences of a produce prescription program. Transl Behav Med. In press.

Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care [IPFCC]. Advancing the practice of patient- and family-centered care in primary care and other ambulatory settings. 2016.

Acknowledgments

We thank participating clinics (Northeast Ohio Neighborhood Health Center, Inc., (NEON) Hough Health Center; St. Vincent Medical Group Medical Arts Physician Center; and Cleveland Clinic Stephanie Tubbs Jones Health Center), providers, FM managers, and patients for their partnership in this work.

Funding

This publication is supported by Cooperative Agreement Numbers 5 U58 DP005851-03 and 1U48DP005013 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Mt. Sinai Healthcare Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All study procedures were approved by the MetroHealth Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services. No copyrighted materials, survey, instruments, or tools were used.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schlosser, A.V., Smith, S., Joshi, K. et al. “You Guys Really Care About Me…”: a Qualitative Exploration of a Produce Prescription Program in Safety Net Clinics. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 2567–2574 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05326-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05326-7