Abstract

Background

Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) and related models of medical tele-education are rapidly expanding; however, their effectiveness remains unclear. This systematic review examines the effectiveness of ECHO and ECHO-like medical tele-education models of healthcare delivery in terms of improved provider- and patient-related outcomes.

Methods

We searched English-language studies in PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO databases from 1 January 2007 to 1 December 2018 as well as bibliography review. Two reviewers independently screened citations for peer-reviewed publications reporting provider- and/or patient-related outcomes of technology-enabled collaborative learning models that satisfied six criteria of the ECHO framework. Reviewers then independently abstracted data, assessed study quality, and rated strength of evidence (SOE) based on Cochrane GRADE criteria.

Results

Data from 52 peer-reviewed articles were included. Forty-three reported provider-related outcomes; 15 reported patient-related outcomes. Studies on provider-related outcomes suggested favorable results across three domains: satisfaction, increased knowledge, and increased clinical confidence. However, SOE was low, relying primarily on self-reports and surveys with low response rates. One randomized trial has been conducted. For patient-related outcomes, 11 of 15 studies incorporated a comparison group; none involved randomization. Four studies reported care outcomes, while 11 reported changes in care processes. Evidence suggested effectiveness at improving outcomes for patients with hepatitis C, chronic pain, dementia, and type 2 diabetes. Evidence is generally low-quality, retrospective, non-experimental, and subject to social desirability bias and low survey response rates.

Discussion

The number of studies examining ECHO and ECHO-like models of medical tele-education has been modest compared with the scope and scale of implementation throughout the USA and internationally. Given the potential of ECHO to broaden access to healthcare in rural, remote, and underserved communities, more studies are needed to evaluate effectiveness. This need for evidence follows similar patterns to other service delivery models in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Technological innovations over the past decade have steadily reduced barriers to accessing healthcare1 both in the USA2 and internationally.3 Telemedicine holds the potential for patients to seek medical expertise more efficiently, reducing wait times and allowing specialists to direct their attention to individuals with the greatest health needs, regardless of geographic location.4 This is particularly true for the expertise of specialists, which may be unevenly distributed.5

Several mechanisms have arisen to enable increased access to specialist care, including e-consultations that allow specialists to consult remotely.6 However, with a growing physician and nursing shortage in settings ranging from the USA7 to large parts of sub-Saharan Africa,8 there is a fundamental need to equip front-line providers in rural areas with the specialized skills necessary to address community needs themselves. Such capacity-building is particularly relevant in the context of escalating health epidemics, such as the US opioid crisis or recent Ebola epidemic in West Africa, and for tackling increasingly common conditions like hepatitis C.

In 2016, the US Congress passed the ECHO (Expanding Capacity for Health Outcomes) Act, which aims to support and promote “technology-enabled collaborative learning and capacity building models.9” Several such models have been developed, the most ubiquitous being Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes).10 Project ECHO involves pairing front-line clinicians, typically located in underserved areas, with specialist mentors at academic medical centers, or “hubs”, using videoconference and a case-based mode of pedagogy. Launched in 2003 out of the University of New Mexico to increase access to hepatitis C treatment in parts of the rural southwest, the program now operates at more than over 100 academic and medical hubs across 48 states as well as multiple continents, and covers dozens of disease states and health conditions.11

While Project ECHO has been successful at expanding its scope and scale, there remains a paucity of evidence regarding the impact of ECHO and ECHO-like models (EELM) on provider- and patient-related outcomes. An investigation of the evidence is particularly warranted, given the extent of human and financial capital invested in this model: thousands of trainers and trainees, and millions of dollars in financial support. While an earlier review examined the impact of ECHO through the middle of 2015,12 this was prior to the ECHO Act and any experimental evidence, and did not extend beyond ECHO-affiliated programs. We present a systematic review of EELM that comprises peer-reviewed evidence of patient and provider outcomes between 2007 and 2018. We follow Cochrane Collaboration’s GRADE framework13 to examine the strength of evidence (SOE) and use this review as a basis for highlighting potential next steps and future directions.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

We reviewed academic literature in accordance with PRISMA guidelines,14 targeting publications that evaluated EELM (2007–2018). In consultation with public health experts in the field of telehealth, we established an operational definition for EELM as “a technology-enabled educational model, in which a mentor with specialized knowledge provides interactive and case-based guidance to a group of mentees for the purpose of strengthening their skills and knowledge to provide high-quality healthcare.” We delimited our search according to six inclusion criteria: (1) using a technology-enabling platform, (2) having a health-focused objective, (3) leveraging specialists to train generalists, (4) using interactive mentorship, (5) using case-based learning, and (6) implementing a hub-spoke framework rather than 1:1 learning.

We implemented a Boolean search procedure based on key words defined under three domains: (i) a technology-enabling component, (ii) involvement of health providers, and/or (iii) terms denoting resource or geographic barriers, which EELM often address. As a complementary strategy, we searched for ECHO-specific terminology linked by “or” statements. A detailed list of search terms can be found in Appendix Table 1 (online). A total of six databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, the Cochrane Central Register (CENTRAL), and Scopus. Google Scholar was limited to the first 100 returns. Using seminal articles, including a 2016 review by Zhou and colleagues,12 we also examined bibliographies.

Study Selection

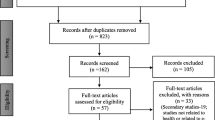

We limited results to peer-reviewed articles reporting provider- or patient-related outcomes published in English between January 1, 2007 and December 1, 2018, including articles originating outside the USA. Returns were screened independently by two research team members for agreement with the six inclusion criteria. For situations in which agreement with criteria was unclear from the title and abstract, the full text was reviewed. Records that met inclusion criteria were flagged for full data abstraction (see Fig. 1). In the event a discrepancy arose, additional members of the research team were consulted.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Articles meeting inclusion criteria were independently entered by an investigator into a data abstraction form. A second investigator was then tasked with reviewing abstracted data to ensure accuracy and completeness. Summaries of abstracted data can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We selected key features from each study to review and summarize, based on a hierarchy of evidence, with highest quality evidence the focus of synthesis. Provider-related outcomes included participation, satisfaction, knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior change, following a core competencies model for implementation science66 articulated by the National Implementation Research Network.67

Patient-related outcomes were grouped according to health condition and involved careful examination of health condition-specific outcomes as stated in the literature. These were classified as either process or outcome measures, according to US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality68 definitions. Whenever possible, we report summary statistics—including means, standard deviations, odds ratios (ORs), and hazards ratios (HRs). We also report p values and 95% confidence intervals.

We rated SOE according to Cochrane GRADE criteria,13 following a two-step process. First, two research team members independently assigned a score to each article for the outcomes presented within, based on six GRADE characteristics: study design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. The full research team collectively reviewed each score. Second, the research team deliberated weight of evidence across individual studies for each patient- and provider-related outcome. This systematic classification process is outlined in detail on the Cochrane website and involves, for example, evaluating the quantity of experimental versus observational evidence, and studying effect sizes and dose responses. SOE is assigned an ordinal score: very low (+), low (++), medium (+++), high (++++) (Table 3).

Role of the Funder

This investigation was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), within the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).69 In accordance with the ECHO Act of 2016, this investigation was commissioned as part of a Report to US Congress, released in 2019. Two staff members from ASPE are co-authors; the staff contributed to the selection of terms for the literature search and the criteria for study eligibility and provided edits of the final manuscript.

RESULTS

After implementation of search procedures, we reviewed 2970 records: 2965 from database searches, and an additional five from bibliographic reviews. There was an acceptable degree of inter-rater reliability: raters agreed 97.3% of the time, reflecting kappa coefficient of κ = 0.46. Following screening, 211 articles were identified for full-text review for eligibility. Of these, 52 met eligibility (see Fig. 1). Forty-three contained provider outcomes, 15 contained patient outcomes, and six contained both provider and patient outcomes.

The most common health topics addressed by EELM were hepatitis C, chronic pain management, and dementia and elderly care. Thirty-nine of 52 articles focused on EELM implemented in the USA, with Canada and Australia as the next most common countries. Year by year, there has been an overall increase in the number of published articles evaluating EELM (see Fig. 2).

The format of sessions ranged from weekly to monthly, lasting 60 to 180 min per session, with wide variation in number of sessions conducted—in part because of the continuous nature of intervention protocols. Similarly, there was variability in the number of trainees and number of patients served by trainees. In some instances, these numbers were not reported. Below, we present a topical synthesis of the articles, organized by provider-related outcomes and patient-related outcomes; a full description of outcomes reported is found in the Online Appendix.

Provider-Related Outcomes

Between 2007 and 2018, 43 of 52 articles presented quantitative or qualitative evidence outlining provider-related outcomes of EELM. Studies most frequently measured outcomes in one of four areas: (i) provider satisfaction with quality and content of trainings (n = 17; 40%); (ii) provider knowledge acquired (n = 18; 42%); (iii) enhanced provider confidence or self-efficacy associated with care delivery (n = 18; 42%); and (iv) changes in self-reported provider behaviors associated with patient care (n = 7; 16%). In terms of study design, 23 of 43 (53%) involved a counterfactual—either within- (pre vs. post) or between-subjects. While only one of the studies included an element of randomization, three studies involved both within- and between-subject comparisons.

Provider Satisfaction

Assessment of provider satisfaction largely entailed administration of post-intervention structured surveys.19, 23,23,25, 27, 33, 34, 41, 44, 50, 70 The median response rate was low (under 50%); however, self-reports consistently indexed positive ratings, at both the item-level and survey-level. In several instances, satisfaction was framed in terms of participation benefits, such as “Because of [EELM], I have expanded my practice to include new skills.19” In addition to structured surveys, several authors conducted focus group discussions17, 20, 33, 54 and semi-structured interviews24, 28, 43, 53 to solicit feedback on aspects of EELM that worked well or less well, often with a focus on acceptability of the technology platform utilized. Here, responses were also generally positive.

Provider Knowledge

In one study,42 authors evaluated provider knowledge by merely asking participants after training to self-report whether they perceived their knowledge to improve. More often, studies implemented a pre-post design, in which providers were asked to self-assess their knowledge at baseline and again at endline, with significant changes observed.17, 36, 38, 39, 51, 52, 56, 71 In a subset of assessments, knowledge surveys were constructed by the authors and administered.15, 23, 26, 39, 41, 47 The authors found significant improvements in objectively measured content knowledge. By contrast, a cluster randomized controlled trial on chronic pain education did not show knowledge gains among ECHO participant clinics compared with non-participant clinics.26

Provider Confidence

Change in confidence and self-efficacy focused on whether providers reported greater confidence in ability to diagnose and/or treat patients following EELM participation.17, 23, 26, 30, 32, 34, 41, 48, 51, 52, 56, 71 Metrics along these lines were reported in most studies, ranging from self-reported changes following participation,32 to within-subjects change from baseline to endline,48 to between-subjects comparisons in perceived competence,30 including in one randomized controlled trial (RCT).26 In most instances, results were positive and significant; a notable exception came from the RCT on chronic pain management.26

Provider Behavior Change

Several studies administered surveys in which providers were asked to self-report behavior change as a result of participating in case presentations. For example, Komaromy and colleagues35 found 77% of participants reported that case discussion changed their patient care plan. Likewise, Catic and colleagues21 observed that recommendations for treatment were incorporated by case presenters 89% of the time. Qaddoumi and colleagues46 reported that 91% of case presenters followed recommendations. In other studies, providers were merely asked via survey whether EELM participation had or would alter care provision19, 43; on such occasions, providers responded positively.

Patient-Related Outcomes

Fifteen of 52 identified studies (29%) discussed patient-related outcomes, including changes in care processes and outcomes of care. Few studies examined cost of care.

Hepatitis C

Four studies reviewed hepatitis C outcomes. Arora and colleagues16 compared sustained virologic response (SVR) between patients at training versus trainee sites and found no difference (p > 0.05), indicating trainees (generalists) performed at a level comparable to trainers (specialists). Similarly, Mohsen and colleagues62 compared 100 patients of providers who participated in an EELM to 100 patients who received care in a tertiary liver clinic (TLC). Initiation of direct-acting antiviral therapy was similar between groups (EELM, 78%; TLC, 81%), as was completion of treatment (EELM, 89%; TLC, 86%) and—to a lesser extent—SVR (EELM, 87%; TLC, 96%). Statistical significance was not reported.

Beste and colleagues18 identified providers trained via EELM, and compared likelihood of patient treatment initiation among EELM participants and non-participants. The authors found treatment initiation was higher among trainees (hazard ratio [HR], 1.20; p < 0.01), but this effect was a result of increased initiations among only those patients presented in case discussions (HR, 3.30; p < 0.01). Ní Cheallaigh and colleagues43 conducted a series of semi-structured interviews with EELM trainees. Interviewees reported that patients attending their practice were beneficiaries of ECHO. For example, one trainee remarked, “Now, access to specialist clinics has improved. [The local specialist] has actually taken back some people he discharged. He’s also seen a couple of new people.43”

Chronic Liver Disease

We identified two studies on chronic liver disease. The first, by Glass and colleagues,29 found that EELM training allowed patients to access care an average of 9.6 days sooner and saved 250 miles of travel compared with those seeking in-clinic specialty care. A second study, by Su and colleagues,64 examined the effect of receiving a virtual consultation through the VA’s SCAN-ECHO program. Between 2011 and 2015, 513 veterans with chronic liver disease received a virtual consultation from a SCAN-ECHO provider, while 62,237 did not. After propensity score matching on characteristics predictive of receiving a visit, researchers found hazard ratio of all-cause mortality among those receiving a virtual consultation to be 0.54 (p = 0.003), compared with no visit.

Chronic Pain Management and Opioid Addiction

Four studies examined chronic pain management. Anderson and colleagues15 compared providers at community health centers who participated in EELM trainings with those who did not. They found, among those who participated, the percent of patients with an opioid prescription declined from 56.2 to 50.5% (p = 0.02), with no decline observed in the comparison group. Conversely, referrals for behavioral health and physical therapy increased (p < 0.001). Two other studies, by Katzman and colleagues61 and Frank and colleagues,59 examined prescription and referral rates, respectively. Katzman and colleagues61 inspected opioid prescription rates across 1382 clinics associated with the Army and Navy, 99 of which participated in an EELM. Compared with patients of providers who did not participate in EELM (n = 1,187,945), those with providers who did participate (n = 52,941) observed a much greater decline in prescriptions: from 23 to 9% (p < 0.001). Meanwhile, Frank and colleagues inspected likelihood of referral among patients presented as EELM cases versus those not presented as cases; cases were more likely to be referred to physical therapy (HR, 1.10; p < 0.05).59 A final study, by Carey and colleagues,58 performed a spatial reach analysis, concluding that patient travel distance to specialty pain care was associated with only slightly lower odds of access to an EELM-trained provider (OR, 0.98; p = 0.01), versus sizably lower odds of care receipt at a specialty care clinic (OR, 0.78; p < 0.001).

Geriatric Care

Three studies examined elderly care for those with mental health conditions, including dementia; one additional study examined transitional care. Catic and colleagues21 studied the effect of adhering to expert recommendations for residents with dementia, and found that providers who followed EELM recommendations were more likely to report “clinical improvement” among patients (74% vs. 20%; p = 0.03). Fisher and colleagues28 examined the relative change in care utilization and costs among elderly patients with mental health conditions, compared with elderly patients without such conditions, before versus after providers participated in EELM training. Among patients with mental health conditions, there was a reduction in emergency department costs: from $406 to $311 (p < 0.05); this reduction was not observed in the comparison group. Gordon and colleagues60 examined quality of care metrics among elderly patients at facilities with providers who were EELM-trained versus not. They observed non-significant differences on primary outcomes (restraint and antipsychotic medication use), but they did find lower rates of urinary tract infections (UTI) among patients seen at facilities with providers trained through EELM (OR for UTI, 0.77; p < 0.05).

Moore and colleagues63 examined transitional care among elderly adults. Among patients with providers at a skilled nursing facility who had participated in EELM training, the authors found shorter lengths of inpatient stay (p = 0.01), lower 30-day hospital re-admission rates (p = 0.03), and lower 30-day care costs (p < 0.001) compared with providers who had not participated. This difference was significant even after adjusting for baseline differences in case mix.

Diabetes Management

Watts and colleagues65 reported training two primary care physicians on diabetes management through EELM. Providers reported that—among patients with poorly controlled diabetes (i.e., all patients with HbA1c > 9%)—mean HbA1c levels decreased from 10.2% before training sessions to 8.4% after training (p < 0.001) 5 months later, a clinically significant difference.

Strength of Evidence

Provider-related outcomes have relied heavily on self-reports for providers who (i) self-select to participate in EELM, (ii) maintain participation in trainings over time, and (iii) complete feedback surveys. The one RCT examining provider-related outcomes concluded null results. Among studies that collected data before versus after EELM trainings, most offered no control group, raising the question of what would have happened in the absence of training, or if EELM trainings were substituted with a different set of learning tools.

Quality of patient-related outcomes varied widely. While mental health and substance use disorders have been the most frequently implemented EELM in the USA, we found no literature describing the impact of EELMs on patient outcomes associated with these conditions apart from among elderly adults. For conditions like osteoporosis, for which there were provider-related outcomes, we identified no articles assessing patient-related outcomes. For hepatitis C, chronic pain management, dementia care, and diabetes, there was at least one article published in which a counterfactual was incorporated. Two studies, one by Anderson and colleagues15 and one by Katzman and colleagues,61 employed quasi-experimental approaches. In a majority of instances, authors identified statistically significant results in favor of EELM. With the exceptions of virologic suppression in the context of hepatitis C and A1C levels in the context of diabetes, reported outcomes were process measures rather than outcome measures.

DISCUSSION

We identified 52 studies between 2007 and 2018 that reported provider- and/or patient-related outcomes from EELM of medical tele-education. Based on our analysis, the empirical evidence for EELM’s impact on patient and provider outcomes is low.

Regarding provider-related outcomes, 43 articles have been published in the past 11 years. Over three-quarters provide no between-subjects comparison group, raising a question as to what would be observed in the absence of intervention or under an alternative intervention. While measures like provider satisfaction and self-efficacy are inherently subjective and susceptible to social desirability bias, such biases could be addressed by the inclusion of an active control condition or a third-party evaluator. In 14 instances, no baseline data were recorded, meaning that change in outcomes due to the intervention was unobservable. For measures like provider knowledge, which can be more objectively measured through formal testing, over half of studies relied on subjective self-reports. The response rate was also as low as 7% of participants, suggesting self-selection bias.37 The one recorded cluster RCT, by Eaton and colleagues,26 did not find a benefit of EELM in terms of provider knowledge or perceived competence.

Arguably, the most important provider-related outcomes are behavior changes. To this end, three studies examined the effect of provider presentations on provider behavior. The authors found that providers who presented cases altered care 77–91% of the time.21, 35, 46 Beste and colleagues18 also found that presenting cases resulted in increased initiation of patient care for hepatitis C. However, increased treatment initiation was only observed among those cases presented during trainings, and not among other patients treated by the same provider. This raises a question of whether EELM are truly building capacity to handle cases without assistance and constitutes an important area for further investigation.

With respect to patient-related outcomes, we identified 15 EELM studies published over the past 11 years. Eleven of these included a comparison group; however, none involved an element of randomization. For all but two measures, outcomes examined were process measures—for example, frequency of prescriptions or number of referrals. While process measures are likely associated with direct patient outcomes, the inferences drawn from these are indirect. However, for three conditions—hepatitis C, dementia care, and chronic pain management—studies showed improvements in different processes and outcomes of care, which suggests that EELM may be beneficial in those conditions.

In terms of direct patient outcome measures, three studies examined the rate of sustained virologic response among individuals treated for hepatitis C. While two articles found that SVR was similar among patients who sought care from EELM trainees and experts16, 62—an indication of project success—another found that SVR did not differ between those seeing providers who received EELM training versus did not receive EELM training.18 In a separate study looking at the effect of EELM on diabetes care,65 the authors found positive results that training led to reductions in patient mean HbA1c values within practitioner panels, a result not found in a comparison group. While results here show promise, the study was limited by sample size, with only 2 EELM providers and 2 control providers.

While existing evidence suggests the potential impact of EELM in improving patient outcomes, our SOE assessment underscores the need for more rigorous evaluation to substantiate the model. One of the main findings is that the quality of evidence for the effectiveness of EELM is generally rated as “low” or “very low” based on the GRADE system. However, it is important to note that this finding is by no means limited to EELM; in fact, many models of service delivery are supported by limited evidence, for example, the widescale initiative of Housing First, which provides rapid housing to improve client housing security and health. While it is a widely used model, only limited evidence exists for its impact on long-term health outcomes, despite four randomized controlled trials.72 Nevertheless, it is appropriate to continue to strive for higher quality evidence.

A few study limitations should be noted. First, while search criteria were meant to be broad, it is possible articles were overlooked, particularly if they did not contain key words in the Appendix Table online. Second, we were unable to include works in progress, though we identified several. Similarly, due to a limited subset of studies that were not ECHO affiliated, we were not equipped to make ECHO versus non-ECHO EELM comparisons, though this may be an interesting avenue to pursue as non-ECHO EELM proliferate.

In summary, we identified 52 articles over the past 10 years which outline provider- and patient-related outcomes from EELM implementations. One of these comprised a randomized controlled trial with non-significant findings, while a plurality were cross-sectional surveys with high risk of bias. Given the capacity-building orientation of EELM, it would be important for studies to include longer periods of follow-up to assess maintenance, as well as to compare the costs and outcomes of EELM to alternative forms of continuing medical education that rely on technology. As noted, models like EELM that are novel within the healthcare delivery landscape are liable to incrementally establish an evidence base. In this respect, our findings are not surprising. Rather, the assessment is meant to provide an inventory of the existing literature, which may establish a benchmark for EELM moving forward.

References

Kvedar J, Coye MJ, Everett W. Connected health: A review of technologies and strategies to improve patient care with telemedicine and telehealth. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2014;33(2):194–9.

Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med 2016;375(2):154–61.

Alkmim MB, Figueira RM, Marcolino MS, Cardoso CS, Abreu MPD, Cunha LR, et al. Improving patient access to specialized health care: The Telehealth Network of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:373–8.

Terwiesch C, Asch DA, Volpp KG. Technology and Medicine: Reimagining Provider Visits as the New Tertiary Care. Ann Intern Med 2017;167(11):814–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/m17-0597

Ricketts TC. The migration of physicians and the local supply of practitioners: a five-year comparison. Acad Med 2013;88(12):1913–8.

Liddy C, Rowan MS, Afkham A, Maranger J, Keely E. Building access to specialist care through e-consultation. Open Med 2013;7(1):e1.

Kirch DG, Petelle K. Addressing the physician shortage: The peril of ignoring demography. JAMA. 2017;317(19):1947–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.2714

Kinfu Y, Dal Poz MR, Mercer H, Evans DB. The health worker shortage in Africa: Are enough physicians and nurses being trained? : SciELO Public Health; 2009.

ECHO Act, Pub L No. 114–270, 130 Stat 1395 (2016).

University of New Mexico. Project ECHO. Available at: https://echo.unm.edu/. Accessed June 16, 2019.

Fischer SH, Rose AJ, McBain RK, Faherty LJ, Sousa J, Martineau M. Evaluation of technology-enabled collaborative learning and capacity building models: Materials for a report to Congress. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2019. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2934.html.

Zhou C, Crawford A, Serhal E, Kurdyak P, Sockalingam S. The impact of Project ECHO on participant and patient outcomes: A systematic review. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 2016;91(10):1439–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001328

Ryan R, Hill S. How to GRADE the quality of the evidence. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group. 2016. Available at: http://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources. Version 3.0. Accessed June 16, 2019.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151(4):264–9.

Anderson D, Zlateva I, Davis B, Bifulco L, Giannotti T, Coman E, et al. Improving pain care with Project ECHO in community health centers. Pain Med (Malden, Mass.). 2017;18(10):1882–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx187

Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, Deming P, Kalishman S, Dion D, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med 2011;364(23):2199–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1009370

Ball S, Wilson B, Ober S, McHaourab A. SCAN-ECHO for Pain Management: Implementing a Regional Telementoring Training for Primary Care Providers. Pain Med (Malden, Mass.). 2018;19(2):262–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx122

Beste LA, Glorioso TJ, Ho PM, Au DH, Kirsh SR, Todd-Stenberg J, et al. Telemedicine specialty support promotes hepatitis C treatment by primary care providers in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Med. 2017;130(4):432–8.e3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.11.019

Beste LA, Mattox EA, Pichler R, Young BA, Au DH, Kirsh SF, et al. Primary care team members report greater individual benefits from long- versus short-term specialty telemedicine mentorship. Telemedicine journal and e-health : the official journal of the American Telemedicine Association 2016;22(8):699–706. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2015.0185

Carlin L, Zhao J, Dubin R, Taenzer P, Sidrak H, Furlan A. Project ECHO telementoring intervention for managing chronic pain in primary care: Insights from a qualitative study. Pain Med (Malden, Mass.). 2018;19(6):1140–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx233

Catic AG, Mattison ML, Bakaev I, Morgan M, Monti SM, Lipsitz L. ECHO-AGE: an innovative model of geriatric care for long-term care residents with dementia and behavioral issues. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15(12):938–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.08.014

Chaple MJ, Freese TE, Rutkowski BA, Krom L, Kurtz AS, Peck JA, Warren P, Garrett S. Using ECHO Clinics to Promote Capacity Building in Clinical Supervision. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 54:S275-S280. 2018.

Cofta-Woerpel L, Lam C, Reitzel LR, Wilson W, Karam-Hage M, Beneventi D, et al. A tele-mentoring tobacco cessation case consultation and education model for healthcare providers in community mental health centers. Cogent Med. 2018;5(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2018.1430652

Cordasco KM, Zuchowski JL, Hamilton AB, Kirsh S, Veet L, Saavedra JO, et al. Early lessons learned in implementing a women’s health educational and virtual consultation program in VA. Med Care 2015;53(4 Suppl 1):S88–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000313

Covell NH, Foster FP, Margolies PJ, Lopez LO, Dixon LB. Using distance technologies to facilitate a learning collaborative to implement stagewise treatment. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.). 2015;66(6):645–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400155

Eaton LH, Godfrey DS, Langford DJ, Rue T, Tauben DJ, Doorenbos AZ. Telementoring for improving primary care provider knowledge and competence in managing chronic pain: A randomised controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare. 2018:1357633x18802978. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633x18802978

Farris G, Sircar M, Bortinger J, Moore A, Krupp JE, Marshall J, et al. Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes-Care Transitions: Enhancing geriatric care transitions through a multidisciplinary videoconference. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65(3):598–602. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14690

Fisher E, Hasselberg M, Conwell Y, Weiss L, Padron NA, Tiernan E, et al. Telementoring primary care clinicians to improve geriatric mental health care. Popul Health Manag 2017;20(5):342–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2016.0087

Glass LM, Waljee AK, McCurdy H, Su GL, Sales A. Specialty Care Access Network-Extension of Community Healthcare Outcomes model program for liver disease improves specialty care access. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62(12):3344–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-017-4789-2

Haozous E, Doorenbos AZ, Demiris G, Eaton LH, Towle C, Kundu A, et al. Role of telehealth/videoconferencing in managing cancer pain in rural American Indian communities. Psychooncology. 2012;21(2):219–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1887

Jansen BD, Brazil K, Passmore P, Buchanan H, Maxwell D, McIlfatrick SJ, Morgan SM, Watson M, Parsons C. Evaluation of the impact of telementoring using ECHO© technology on healthcare professionals’ knowledge and self-efficacy in assessing and managing pain for people with advanced dementia nearing the end of life. BMC Helath Services Research, 18:228. 2018.

Johnson KL, Hertz D, Stobbe G, Alschuler K, Kalb R, Alexander KS, et al. Project Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) in multiple sclerosis: Increasing clinician capacity. Int J MS Care 2017;19(6):283–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2016-099

Katzman JG, Comerci G Jr., Boyle JF, Duhigg D, Shelley B, Olivas C, et al. Innovative telementoring for pain management: Project ECHO Pain. J Contin Educ Heal Prof 2014;34(1):68–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21210

Kauth MR, Shipherd JC, Lindsay JA, Kirsh S, Knapp H, Matza L. Teleconsultation and training of VHA providers on transgender care: Implementation of a multisite hub system. Telemedicine journal and e-health : the official journal of the American Telemedicine Association. 2015;21(12):1012–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2015.0010

Komaromy M, Bartlett J, Manis K, Arora S. Enhanced primary care treatment of behavioral disorders with ECHO case-based learning. Psychiatr Serv (Washington, D.C.). 2017;68(9):873–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600471

Komaromy M, Ceballos V, Zurawski A, Bodenheimer T, Thom DH, Arora S. Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO): A new model for community health worker training and support. J Public Health Policy 2018;39(2):203–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-017-0114-8

Lewiecki EM, Rochelle R, Bouchonville MF 2nd, Chafey DH, Olenginski TP, Arora S. Leveraging scarce resources with Bone Health TeleECHO to improve the care of osteoporosis. J Endoc Soc 2017;1(12):1428–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1210/js.2017-00361

Marciano S, Haddad L, Plazzotta F, Mauro E, Terraza S, Arora S, et al. Implementation of the ECHO(R) telementoring model for the treatment of patients with hepatitis C. J Med Virol 2017;89(4):660–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24668

Masi C, Hamlish T, Davis A, Bordenave K, Brown S, Perea B, et al. Using an established telehealth model to train urban primary care providers on hypertension management. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012;14(1):45–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00559.x

Mazurek MO, Brown R, Curran A, Sohl K. ECHO Autism. Clinical Pediatrics, 56: 247-256. 2017.

Mehrotra K, Chand P, Bandawar M, Rao Sagi M, Kaur S, G A, et al. Effectiveness of NIMHANS ECHO blended tele-mentoring model on Integrated Mental Health and Addiction for counsellors in rural and underserved districts of Chhattisgarh, India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;36:123–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2018.07.010

Meins AR, Doorenbos AZ, Eaton L, Gordon D, Theodore B, Tauben D. TelePain: A community of practice for pain management. J Pain Relief. 2015;4(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0846.1000177

Ní Cheallaigh C, O’Leary A, Keating S, Singleton A, Heffernan S, Keenan E, et al. Telementoring with Project ECHO: A pilot study in Europe. BMJ Innov 2017;3(3):144–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2016-000141

Oliveira TC, Branquinho MJ, Goncalves L. State of the art in telemedicine - concepts, management, monitoring and evaluation of the telemedicine programme in Alentejo (Portugal). Stud Health Technol Inform 2012;179:29–37.

Parsons C, Mattox EA, Beste LA, Au DH, Young BA, Chang MF, Palen BN. Development of a Sleep Telementorship Program for Rural Department of Veterans Affairs Primary Care Providers: Sleep Veterans Affairs Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes. Annals of American Thoracic Society, 14: 267-274.

Qaddoumi I, Mansour A, Musharbash A, Drake J, Swaidan M, Tihan T, et al. Impact of telemedicine on pediatric neuro-oncology in a developing country: The Jordanian-Canadian experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48(1):39–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21085

Rahman AN, Simmons SF, Applebaum R, Lindabury K, Schnelle JF. The coach is in: Improving nutritional care in nursing homes. The Gerontologist 2012;52(4):571–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr111

Ray RA, Fried O, Lindsay D. Palliative care professional education via video conference builds confidence to deliver palliative care in rural and remote locations. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-272

Salgia RK, Mullan PB, McCurdy H, Sales A, Moseley RH, Su GL. The educational impact of the Specialty Care Access Network-Extension of Community Healthcare Outcomes program. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 20: 1004-8.

Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Firek AF, Garcia R, Mejia S, Laski S, et al. Interdisciplinary Transgender Veteran Care: Development of a Core Curriculum for VHA Providers. Transgender Health 2016;1(1):54–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2015.0004

Sockalingam S, Arena A, Serhal E, Mohri L, Alloo J, Crawford A. Building Provincial Mental Health Capacity in Primary Care: An Evaluation of a Project ECHO Mental Health Program. Academic psychiatry : the journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry 2018;42(4):451–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-017-0735-z

Swigert TJ, True MW, Sauerwein TJ, Dai H. U.S. Air Force Telehealth Initiative to Assist Primary Care Providers in the Management of Diabetes. Clin Diabetes 2014;32(2):78–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.32.2.78

Van Ast P, Larson A. Supporting rural carers through telehealth. Rural Remote Health 2007;7(1):634.

Volpe T, Boydell KM, Pignatiello A. Mental health services for Nunavut children and youth: Evaluating a telepsychiatry pilot project. Rural Remote Health 2014;14(2):2673.

White C, McIlfatrick S, Dunwoody L, Watson M. Supporting and improving community health services--a prospective evaluation of ECHO technology in community palliative care nursing teams. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 9: 202-208.

Wood BR, Mann MS, Martinez-Paz N, Unruh KT, Annese M, Spach DH, et al. Project ECHO: Telementoring to educate and support prescribing of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by community medical providers. Sex Health 2018;15(6):601–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1071/sh18062

Wood BR, Mann MS, Martinez-Paz N, Unruh KT, Annese M, Spach DH, Scott JD, Stekler JD. Project ECHO: telementoring to educate and support prescribing of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by community medical providers. Sexual Health, 15: 601-605.

Carey EP, Frank JW, Kerns RD, Ho PM, Kirsh SR. Implementation of telementoring for pain management in Veterans Health Administration: Spatial analysis. J Rehabil Res Dev 2016;53(1):147–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1682/jrrd.2014.10.0247

Frank JW, Carey EP, Fagan KM, Aron DC, Todd-Stenberg J, Moore BA, et al. Evaluation of a telementoring intervention for pain management in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med (Malden, Mass.). 2015;16(6):1090–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12715

Gordon SE, Dufour AB, Monti SM, Mattison ML, Catic AG, Thomas CP, et al. Impact of a videoconference educational intervention on physical restraint and antipsychotic use in nursing homes: Results from the ECHO-AGE pilot study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17(6):553–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.03.002

Katzman JG, Qualls CR, Satterfield WA, Kistin M, Hofmann K, Greenberg N, et al. Army and Navy ECHO Pain telementoring improves clinician opioid prescribing for military patients: An observational cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4710-5

Mohsen W, Chan P, Whelan M, Glass A, Mouton M, Yeung E, et al. Hepatitis C treatment for difficult to access populations; can telementoring (as distinct from telemedicine) help? Intern Med J 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.14072

Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, Sircar M, Travison TG, Abrams A, et al. Improving transitions to postacute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care Transitions. Am J Med 2017;130(10):1199–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.041

Su GL, Glass L, Tapper EB, Van T, Waljee AK, Sales AE. Virtual Consultations through the Veterans Administration SCAN-ECHO Project Improves Survival for Veterans with Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30074

Watts SA, Roush L, Julius M, Sood A. Improved glycemic control in veterans with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus using a Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes model at primary care clinics. J Telemed Telecare 2016;22(4):221–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633x15598052

Moore JE, Rashid S, Park JS, Khan S, Straus SE. Longitudinal evaluation of a course to build core competencies in implementation practice. Implementation Sci : IS 2018;13(1):106.

Metz A, Louison L, Ward C, Burke K. Global Implementation Specialist Practice Profile: Skills and competencies for implementation practitioners. Chapel Hill, N.C.: National Implementation Research Network and Centre for Effective Services, 2017. Available at: https://fpg.unc.edu/node/9178.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Types of health care quality measures. 2011. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/talkingquality/measures/types.html. Accessed June 16, 2019.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/. Accessed June 16, 2019.

Rahman AN, Schnelle JF, Yamashita T, Patry G, Prasauskas R. Distance learning: A strategy for improving incontinence care in nursing homes. The Gerontologist 2010;50(1):121–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp126

Ricketts EJ, Goetz AR, Capriotti MR, Bauer CC, Brei NG, Himle MB, et al. A randomized waitlist-controlled pilot trial of voice over Internet protocol-delivered behavior therapy for youth with chronic tic disorders. J Telemed Telecare 2016;22(3):153–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633x15593192

Baxter AJ, Tweed EJ, Katikireddi SV, Thomson H. Effects of Housing First approaches on health and well-being of adults who are homeless or at risk of homelessness: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019:jech-2018-210981.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the funders of this project at ASPE. We thank Caryn Marks, Nancy De Lew, and Rose Chu for their support. Among our colleagues at the RAND Corporation, we are grateful to Christine Eibner, Jody Larkin, Justin Timbie, Lisa Turner, Lori Uscher-Pines, Monique Martineau, Paul Koegel, and Tricia Soto.

Funding

This work was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services, under master contract, Building Analytic Capacity for Monitoring and Evaluating the Implementation of the ACA, HHSP23320095649WC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Drs. McBain, Rose, Faherty, and Fischer, as well as Ms. Sousa and Ms. Baxi, report support from ASPE through a contract with the RAND Corporation during the conduct of the study. All remaining authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The authors of this manuscript are responsible for its content. Statements in the manuscript should not be construed as endorsements of ASPE or HHS.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 23 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McBain, R.K., Sousa, J.L., Rose, A.J. et al. Impact of Project ECHO Models of Medical Tele-Education: a Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 2842–2857 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05291-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05291-1